Personal Stories of “Storming the Nation”

“All things are going on gloriously at Nauvoo. We shall make a great wake in the nation. Joseph for President. . . . We have already received several hundred volunteers to go out electioneering and preaching and more offering. We go for storming the nation.”

—Letter, Brigham Young and Willard Richards to Reuben Hedlock, 3 May 1844

As the electioneers began arriving in cities and towns around the nation, newspapers took notice. The Pittsburgh Morning Post reported, “We understand that Jo Smith has sent recently fifty-one missionaries into the different states to preach Mormonism and electioneer for the prophet as a candidate for the presidency.”[1] Articles reprinted from Nauvoo newspapers put the number of electioneers in the hundreds. The major Boston and New York City papers had correspondents attending and reporting on the electioneer conventions in those cities, and their columns were reprinted by other presses. Thus readers throughout the nation knew that Joseph was running for president, electioneers were canvassing in the states, their own political parties were responding, and the Latter-day Saints’ influence on the coming election could have important effects. After Joseph was assassinated, the Niles National Register summed up what some Americans felt about Joseph’s campaign:

Joseph unquestionably indulged some faint hope of extending his rapidly accumulated power from Nauvoo to the extremities of the Union, and dreamed even of expanding those limits far beyond what they now are circumscribed to. His exposé of what he would do if elected president of the United States, his letters to the several candidates, and his nominations by conventions at Boston and elsewhere evince that he was determined to make a demonstration for the capitol and dictatorship.[2]

Joseph and his cadre of electioneer missionaries were determined. Excited with dreams of Zion and theodemocracy, these men were “storming the nation” in hopes of making American and even world history. Little did they know how soon and how abruptly the campaign would end and their efforts would be forgotten.

As the electioneer missionaries departed Nauvoo in the spring and summer of 1844, there was an unusual sense of optimism, enthusiasm, and hope—a palpable excitement. Electioneer George Miller later recorded, “At no period since the organization of the church had there been half so many elders in the vineyard, in proportion to the number of members in the church.”[3] Miller never knew how correct he was. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints would not have another missionary force of more than six hundred until the twentieth century and would never have one as proportionately large as the 1844 electioneer cadre.

On 10 April, the day following the organizing meeting, Lorenzo Snow departed by riverboat for Ohio as the first electioneer missionary. Over the next three months hundreds left Nauvoo. The campaign grew in crescendo as electioneers advocated for the prophet in every state of the Union, generating public support and opposition. The electioneers stumped for an independent candidate in what was perhaps the most partisan political environment in American history. Additionally, they fully advocated the third rail of American politics—religion. In the end this mixture of church and state, coupled with the missionaries’ sacrifices, would forge a unique bond among electioneer missionaries, their prophet, their apostles, and the cause of Zion.

The Charge to Preach

The electioneers preached the gospel of Jesus Christ as restored, primitive Christianity. They usually made appointments to publicly preach at a schoolhouse, courthouse, or home of a friend or family member. Sometimes they preached to individuals and families. Several sermonized at large meetings. For example, Samuel H. Rogers, U. Clark, William A. Moore, James H. Flanigan, and William I. Appleby held a two-day camp meeting, “preaching and testifying” to hundreds.[4] On the other hand, Amasa Lyman disappointedly recorded that one of his gatherings was attended “to my surprise [by] no ladies and some half dozen men and two pigs.”[5] The missionaries preached the basic principles of the Restoration: the Book of Mormon, restored priesthood authority, faith in Jesus Christ, repentance, baptism, and reception of the Holy Ghost. In fact, the Twelve Apostles, while attending the different state conferences, “strictly charged [the missionaries] to keep within the limits of the first principles of the gospel and let mysteries alone.”[6]

The missionaries saw great success in baptizing converts and strengthening members in the outlying branches of the church. Dozens of journals, other documents, and newspapers record hundreds of baptisms. Often they occurred during the prearranged one- or two-day conferences held throughout the states, where members and interested observers gathered to be instructed in the gospel and to hear Joseph’s political platform and the missionaries and local leaders often met to conduct church business. One or more members of the Twelve attended most of the conferences. The 24–25 May conference in Jefferson County, New York, alone counted 150 recent baptisms.[7] One newspaper documented the stunning success of the electioneers: “The Mormons are making converts even in old Connecticut, the land of orthodoxy and steady habits.”[8] David Savage recorded that he “baptized a number upon this mission, the Lord working some mighty cures under [his] hands.”[9]

Though many electioneers traveled by steamboat on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, almost every journal mentioned the exhaustion of what seemed endless (though numbered in many journals) miles of walking, often in extreme weather.[10] Traveling without purse or scrip, they were often denied sustenance and shelter, regularly sleeping outdoors. Henry Boyle penned, “We lay out under a pine tree because no one would keep us overnight.”[11] Though determined to fulfill their missions, the electioneers were often lonely and missed their families, homes, and even native countries. Franklin D. Richards wrote his wife an eloquent love poem asking “God [to] extend thine arms of love around the partner of my heart, since thou hast spoken from above and called me with my all to part.”[12] As he walked through upstate New York, James Burgess longingly reminisced about his native England.[13]

For most electioneers, this was their first time serving as missionaries. Such was the case with twenty-year-old Henry G. Boyle, a Latter-day Saint for only five months. Boyle initially worked with Seabert Shelton, one of the electioneer presidents for Virginia. When the two gave out an appointment to preach, more than five hundred attended. With Shelton delayed, Boyle was asked if he was going to preach or not. “I said I did not know, that I had never attempted to speak in public in all my life,” Boyle latter penned. “I knew I could not preach without the Spirit of God to dictate [to] me. I felt a great burden resting down upon [me] and great embarrassment at the idea of trying to preach, and yet felt it would be my duty to try. Therefore I made up my mind I would get up and open my mouth and whatever the Lord wished me to say to that people, he would give it to me.” Shelton did arrive but asked Boyle to preach. Boyle later wrote, “I never had such a flow of the Spirit of the Lord before that time and but seldom since.”[14]

Many electioneer missionaries labored in their home states and while there visited family members, some of whom they baptized. James Holt and his companion Jackson Smith arrived at Holt’s father’s residence in Wilson County, Tennessee. Holt introduced Smith to his father, “but he [Holt’s father] refused to shake hands with him.” Even though Jackson Smith was not a relative of Joseph Smith, Holt’s father “said he had heard enough about the Smiths, and he did not want to see any of them.” Holt retorted that “if he could not entertain [his] fellow-traveler and treat him as a gentleman” they would seek accommodations elsewhere. Holt recorded his father’s response: “This cut my father to the quick, and with tears in his eyes, he said, ‘James, take your friend in and make yourselves welcome.’” Holt enjoyed the time with his family, spending several days visiting with them and “teaching them the principles of the gospel when they gave [him] an opportunity.”[15] His older brother, a Baptist minister, allowed them to preach in his church.

Daniel D. Hunt and his companion Lindsey A. Brady visited Hunt’s family in Kentucky. While preaching there, the people paid “good attention” and nineteen were baptized, including twelve members of Hunt’s extended family.[16] Guy M. Keyser visited and baptized his mother in upstate New York. David Pettegrew mentioned preaching “the truth to thousands of people” and visiting his “relations in Vermont and New Hampshire.”[17] William R. R. Stowell arrived in New York to find many of his relatives receptive to baptism. Stowell’s companion William K. Parshall stayed with him after their missions, and the two led a group of converts to Nauvoo in 1845.[18] Edson Whipple visited and baptized family members in Pennsylvania and New York.[19] Moses and Nancy Tracy took their little family to visit relatives in New York. Nancy recorded, “We ended our visit for this time with my relatives, not forgetting to preach to them the gospel and give them Joseph’s views on the policy of the government.”[20] None joined.

During their preaching, the electioneers sometimes debated with ministers of other faiths, often priding themselves on their performances. Edson Barney noted that his debate in Chicago with a Presbyterian minister went “in my favor.”[21] Levi Jackman’s audience listened to him intently during a debate, leaving when the opposing minister spoke and returning when Jackman recommenced.[22] William Hyde converted and baptized a minister, as did several other electioneers.[23]

Church leaders ordained at least forty electioneers to higher priesthood offices, either in preparation for or because of added responsibilities while on their missions. Most were made Seventies during or immediately following the April conference. A handful were ordained high priests.[24] James H. Glines, a recent convert and a deacon, attended a conference in Boston and was ordained an elder.

The electioneer cadre understood that preaching the restored gospel was a vital part of their assignment. Their efforts produced converts and strengthened local branches. The constant preaching also solidified their own faith. As they sacrificed for Zion, their desire to establish it deepened. Friendships and even marriages were formed. The opportunity of working with and hearing the teachings and testimonies of the Twelve Apostles bolstered their loyalty to these leaders—a foundation that would become immensely important when Joseph’s death led to diverse succession claims.

The Charge to Electioneer

The electioneers undertook their campaign duties with fervor. They understood their call was to preach politics as well as religion. Joseph Holbrook sounded forth the merits of Joseph’s Views “almost daily.”[25] In Delaware Jonathan O. Duke steadily promoted “Joseph Smith’s nomination for President of the United States.”[26] David Fullmer repeatedly addressed large assemblies in Michigan on what he termed “politicks.”[27] In upstate New York on 18 June 1844, Franklin D. Richards gave, in his words, “the first political speech I ever delivered.” The next morning “I called the elders together and told them what I had learned during the night upon the subject relative to the course to be pursued in lecturing from Gen. Smith’s views on politics.”[28] David Savage’s wife Mary, who accompanied him on his mission, recorded that he politicked “with great zeal.”[29] German-immigrant brothers George C. and John J. Riser returned to the German-speaking areas of Ohio they knew as youths to preach and campaign. They used their father’s house as their headquarters, distributing political and religious pamphlets throughout the region.[30] Crandell Dunn’s day-to-day account of his work in Michigan is replete with references to preaching and politics.[31] Often companions team-taught, the first preaching the gospel and the second lecturing on politics.[32]

The travels and activities of Alfred Cordon and fellow English convert James Burgess reveal the dual nature of the electioneers’ assignment. They began their journey in several days of torrential rain with little shelter. They were often “tormented with mosquitos,” illness, and fatigue. Walking an average of twenty miles a day, the elders stopped to preach and campaign to anyone who would listen. As they worked through Illinois they met sharp resistance. They often heard people denounce “Joe Smith” as a “false prophet” threaten them or Joseph with personal harm.

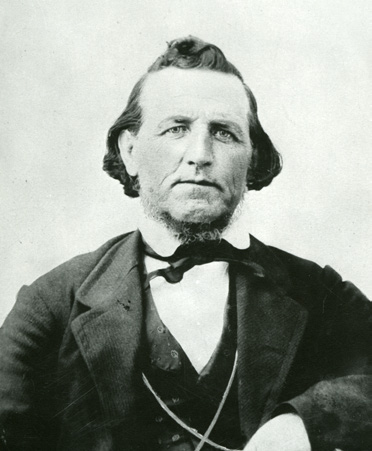

Impoverished British converts Alfred Cordon (top) and James Burgess (bottom) traversed 1,100 miles on foot to Burlington, Vermont, in two months, preaching and electioneering all along the way. Courtesy of Alfred Cordon Family Association and Joyce Richmond (Burgess).

Impoverished British converts Alfred Cordon (top) and James Burgess (bottom) traversed 1,100 miles on foot to Burlington, Vermont, in two months, preaching and electioneering all along the way. Courtesy of Alfred Cordon Family Association and Joyce Richmond (Burgess).

Arriving in Chicago, Cordon and Burgess were unable to find work to pay for steamboat passage to Buffalo. After attending a church conference there, they continued their journey to Vermont, walking through Indiana, Michigan, and New York. As they traveled, they stayed with families and “converse[0] with them on the subject of religion [and] explained to them the principles of the doctrine of Christ . . . [and then] read to them General Smith’s views on the power and policy of the government of the United States.” On 27 June 1844, the day of Joseph’s assassination, Cordon and Burgess reached Niagara Falls amid a downpour. They stopped at the Hill Cumorah a few days later, where the prophet had retrieved the gold plates. They continued to Syracuse, New York, preaching and campaigning there several days. The two companions finally reached Vermont on 20 July and remained there preaching until the spring of 1845, finishing their one-year mission. Burgess married a local Latter-day Saint, and the three returned to Nauvoo.[33]

Sectional Electioneering

Those appointed to be presidents of the electioneers in the different states concentrated their work, and that of their men, on Joseph’s campaign. Their journals, and those of their fellow electioneers, describe organized, deliberate, and focused electioneering.

Illinois

On 21 May 1844, four days after the state convention in Nauvoo, approximately one hundred missionaries left Nauvoo on the steamboat Osprey—the largest such cohort to leave in one day. The topic of conversation among the passengers turned to Joseph’s candidacy. The passengers who were not Latter-day Saints held a mock vote with encouraging results: Joseph Smith, 64; Henry Clay, 46; and Martin Van Buren, 24.[34] Moreover, some people in eastern Illinois, upon hearing Joseph’s political ideas, declared they were “the best [they] ever heard.”[35] On 17 June at the Ottawa, Illinois, conference, apostle George A. Smith and some electioneers addressed a meeting of five hundred using Joseph’s Views. Smith recorded that the people “applauded the sentiment very highly and seemed much pleased.”[36]

In Chicago, electioneer leaders held a meeting to rally support for the campaign. James Burgess and Alfred Cordon “placarded the city with written handbills” in order to invite all to attend and hear Joseph’s views on government. About a dozen electioneers, members of the Chicago branch, and several dozen interested people gathered and elected Cordon president of the proceedings.[37] Electioneers reported, “Joseph’s views and measures are liked very much, though many are opposed to the man.”[38] Jacob E. Terry subsequently placed an order in Chicago for one thousand copies of Views. Trying to sell them on the streets and house to house, Terry had little success interacting with “all manner of men” and was constantly “ordered away from people’s doors.” For the next two weeks, he alternately worked for money, purchased more copies of Views, and attempted to sell them. Often he just gave them away. Leaving Chicago on 14 June, Terry continued to distribute Views daily at homes, religious camp meetings, and public debates throughout Illinois and Indiana.[39]

The Midwest

Amasa Lyman and George P. Dykes led Joseph’s election efforts in Indiana as campaign presidents. However, they did not leave Nauvoo until 4 June 1844, two days after electioneers held the first conference in Indiana.[40] Soon separated, the two presidents did not completely organize the work before the campaign collapsed as a result of Joseph’s death. Yet up until then, and in addition to the planned conferences there, electioneers labored diligently throughout Indiana. William R. R. Stowell and his companion William H. Parshall had breakfast at the home of a family member when Stowell began reading Views to the elderly grandfather of the home. “The gentleman seemed very much interested and inquired earnestly, ‘Who is this Joseph Smith?,’” wrote Stowell. After explaining that Joseph “was the prophet and the leader of the Mormon Church, and that the pamphlet he was reading contained his views on the principles of government, the gentleman said he had served under Washington in the Revolutionary War and that what he had heard sounded very much like Washington’s views.”[41]

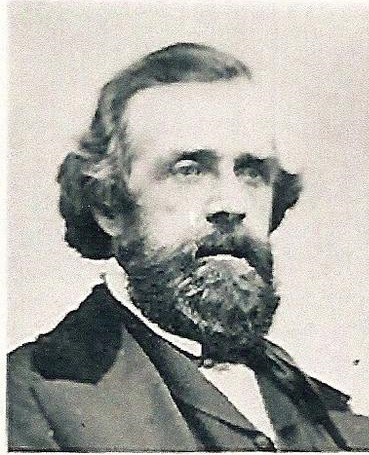

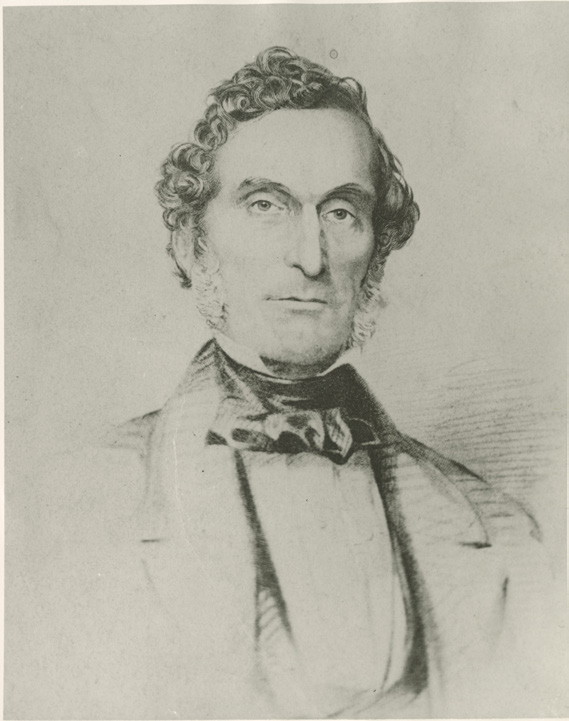

Council of Fifty member Amasa

Council of Fifty member Amasa

Lyman led the electioneering effort

in Indiana with George P. Dykes.

Engraved sketch from 1855 by

Frederick Piercy courtesy of Church History Library.

In neighboring Ohio, Lorenzo Snow and Lester Brooks were the campaign’s presidents. Brooks was already living in Kirtland, serving as the stake president. Snow closed his school in Nauvoo when he was called “by the Twelve on a political mission to Ohio . . . to form a political organization throughout the state . . . for the promotion of Joseph for the presidency.” Snow left on 10 April, the day after the conference meeting in Nauvoo was held to recruit and organize the electioneer missionaries. He gave “on the steamer Osprey the first political lecture that was ever delivered to the world in favor of Joseph for the presidency.”[42] On 7 June near Kirtland, Ohio, “lawyers and doctors . . . called to talk of and obtain Gen. Smith’s views” from apostle Brigham Young and Franklin D. Richards, who were on their way to New York.[43]

Snow and Brooks presided over a “large convention in the temple in Kirtland” on 23 June 1844. For a candidacy that was unapologetically blurring the lines between church and state, the temple was a perfect venue for the convention. Snow and Brooks assigned their missionaries to each of Ohio’s congressional districts. In the following days they printed more than a thousand copies of Joseph’s Views. Snow wrote, “I then procured a horse and buggy and traveled through the most populous portions of the country, lecturing, canvassing, and distributing pamphlets.” He “had a very interesting time—had many curious interviews, and experienced many singular circumstances, on this my first and last electioneering tour.” Snow remembered, “Many people, both Saints and gentiles, thought this a bold stroke of policy, [and] our own people generally, whom I met, were quite willing to use their influence and devote their time and energies to the promotion of the object in view.” Reaction to Joseph’s campaign was mixed: “To many persons who knew nothing of Joseph but through the ludicrous reports in circulation, the movement seemed a species of insanity, while others, with no less astonishment, hailed it as a beacon of prosperity to our national destiny.”[44]

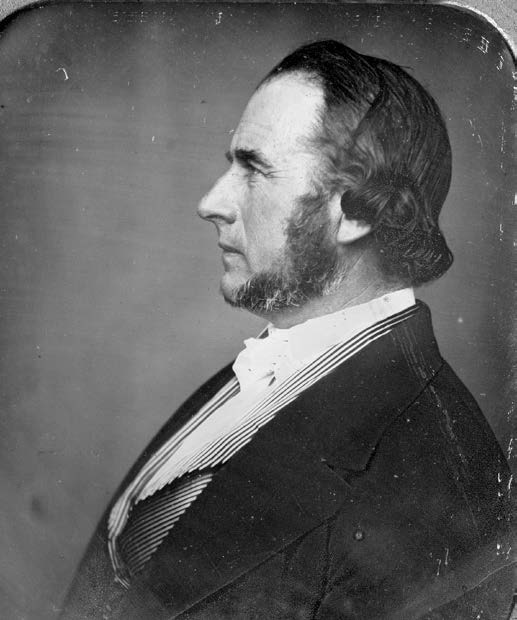

Charles C. Rich (above) and Harvey Green (below) built an impressive political machine for Joseph in Michigan. Courtesy of Church History Library and Glen Parker.

Charles C. Rich (above) and Harvey Green (below) built an impressive political machine for Joseph in Michigan. Courtesy of Church History Library and Glen Parker.

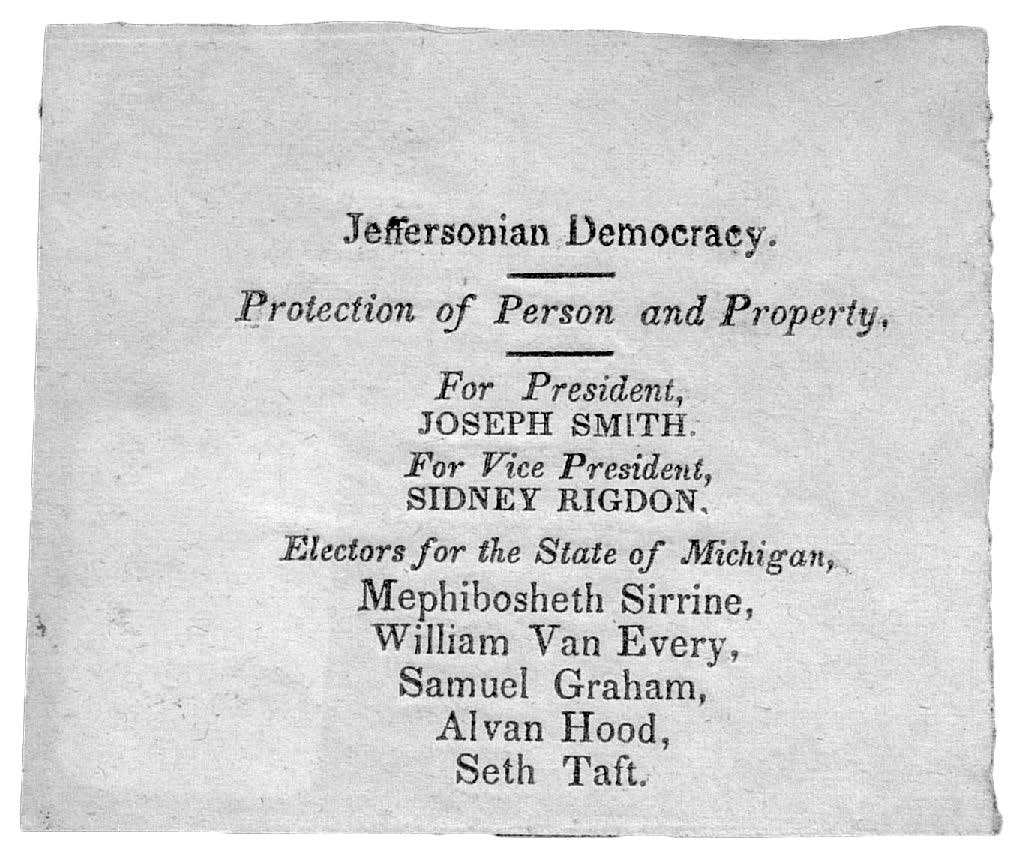

Presidents Charles C. Rich and Harvey Green built a strong political machine in Michigan. Rich, a member of the Council of Fifty, departed Nauvoo on 15 May in company with David Fullmer, Norton Jacob, and Moses Smith. On their way to Michigan they delivered “political lecture[s]” in private homes and public forums. Within days Rich was traveling and campaigning with apostles and fellow Council of Fifty members Wilford Woodruff and George A. Smith. In Kalamazoo, Michigan, on 30 May, the trio spoke at a “political meeting.” They then convened a two-day conference at nearby Comstock in the spacious barn of local branch president Ezekiel Lee: “A large and respected audience was assembled . . . composed of many of the most respectable citizens of the county.” Apostles Wilford Woodruff and George A. Smith, along with Zebedee Coltrin, David Fullmer, Samuel Bent, and Charles C. Rich, spoke to an “audience who sat in silence manifest[ing] great interest and attention.” At the close of the meeting, “that warmth of friendship and feeling of kindness that marks the noble and generous good was manifested by many of the assembly, among whom was Gen. [Horace H.] Comstock and Dr. Hoods.”[45] Comstock was the town’s namesake and a current state senator. The large congregation of Saints and gentiles accepted Joseph’s Views with “good satisfaction.”[46] On the second day, Rich and Green assigned electioneers to campaign in the different counties of Michigan.[47]

The two presidents then returned to Kalamazoo to preside over “a political meeting in the courthouse.” Over the next fortnight, Rich and Green, accompanied at times by other electioneers, preached and politicked throughout Michigan. After a political meeting in Troy Grove, where Rich, David Fullmer, and Norton Jacob read Views and gave lectures on politics, “the people appeared well satisfied.”[48] On 14 June they held another political rally in Franklin, ahead of the scheduled two-day conference there. The day following that conference, Rich and Green held a public “political discussion” before moving on to Detroit. Returning to Franklin, Rich delivered another “political lecture.” On 2 July he and Green returned to Pontiac and took delivery of their order for five thousand copies of Joseph’s Views. They proceeded to Jackson, where on 6 July they held the state convention in the city courthouse.[49] The convention nominated electors to represent Michigan at the national convention, and the electioneers returned to their assigned counties to politick and distribute Views.

The South

John D. Lee, electioneer president for Kentucky, presided over a conference on 13 June 1844 in Lebanon County to “organize the efforts” of the missionaries.[50] Later, Lee would remember, “I felt highly honored to electioneer for a Prophet of God.”[51] One of his fellow missionaries was George Miller, a Council of Fifty member who “preached and electioneered alternately.” While attending a large political barbeque, he stood “on the outskirts of the immense crowd reading to a few of [his] old acquaintances Joseph Smith’s views of the powers and policy of government.” In time the crowd listening to Miller numbered more than those listening to the candidate who was speaking. Miller later recorded: “I got on a large stump and commenced reading aloud Joseph’s views on the powers and policy of government, and backed it up with a short speech, at the end of which I was loudly and repeatedly cheered; and a crowd bore me off about two miles to a Mr. Smith’s tavern, where they had a late dinner prepared for my benefit, all declaring that I should not partake of the barbecue prepared for the candidate who addressed the log cabin meeting, that I was worthy of better respect.”[52]

Jeffersonian Democracy pamphlet containing the Michigan electors

Jeffersonian Democracy pamphlet containing the Michigan electors

for Joseph’s campaign. Courtesy of Church History Library.

William L. Watkins found a good reception for Joseph’s Views even in the slave state of Kentucky. He wrote, “I found my friends willing to listen and conversed on the political situation although I was in a slave state. The question of slavery as advocated in the views of the document I carried found great favor.”[53] Joseph Holbrook and John Outhouse “continued to preach and put forth Joseph Smith’s views, which the people generally liked well,” although they did not approve of a “Mormon prophet for president of the United States.”[54] For many, the political ideas were acceptable, sometimes even preferred, but the candidate was not.

In neighboring Tennessee, Abraham O. Smoot and Alphonso Young managed Joseph’s campaign. They led a conference at Dresden in the Weakley County courthouse on 25–26 May 1844 to organize the campaign and make assignments. They met with stiff resistance on the first day that ended in a chaotic, bloody affair. Held in a private home the next day, the conference arranged geographic campaign assignments and duties to print and distribute Joseph’s Views. Smoot and Young presided over a second conference in Eagle Creek, Benton County, in early June.[55] From 9 to 11 June, Young, along with several electioneer missionaries, preached and politicked at the conference in Dyer County. Young “called their attention to the murders and robberies committed on [their] people, in this once happy land, merely on account of the religion.” Warning them “against tolerating such cruel deeds,” Young laid “General Smith’s claims before them.” Moved by Young’s words, six people were baptized and many more committed to Joseph’s campaign.[56] One of Young’s men, William W. Riley, wrote in his journal that he “delivered a political address to the entire satisfaction of the hearers.”[57]

Following the first conference, Smoot contracted in nearby Paris, Tennessee, for the printing of three thousand copies of Views for a thousand dollars. When he returned to retrieve the copies, a lawyer named Fitzgerald intercepted him. He threatened to prosecute Smoot for allegedly violating an 1835 Tennessee law that forbade “any publications to be made in this state or circulated therein that [were] calculated to excite discontent, insurrection, or rebellion amongst the slaves or free persons of color.” Though confident he was not violating the statute, Smoot chose to desist from printing until he could “get word from headquarters.” Meanwhile, he and his men attended another conference in Benton County with a large and attentive audience without incident. Smoot later returned and paid the printer in Paris for the three thousand copies of Views, which he never received.[58]

Seabert Shelton was one of three presidents for Virginia, having received his appointment very early since he was already organizing the work there in April 1844.[59] Yet in the Deep South there was little evidence of campaign success. Several factors may account for this. First, Church leaders assigned very few electioneers to Arkansas, Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and the Carolinas. Second, Joseph’s proposal that the federal government purchase freedom for slaves would not likely have been embraced in slavery’s stronghold. Third, because none of the electioneers assigned to the Deep South kept a journal of their missions, all evidence of Latter-day Saint political activity there comes from secondhand sources or inference. It does seem that the electioneers had limited religious success in Mississippi and Alabama. Examples are cousins John and Robert Thomas, who were originally assigned to Kentucky but carried their work to Mississippi to little avail.[60]

New England

Although Josiah Butterfield and Elbridge Tufts were made responsible for Maine, Butterfield was delayed and never left Nauvoo. Maine was the farthest electioneering locale from Illinois, and the campaign there did not start until a week after Joseph’s death (that devastating news would travel slowly). Sylvester B. Stoddard was the first missionary to reach Maine, in late June. He busily prepared for the Scarborough conference, which was to be held on 6–7 July. Apostle Wilford Woodruff and Milton Holmes arrived on 3 July after attending the Boston conference and convention. Tufts arrived two nights later, and the next morning the four electioneers were joined by Samuel Parker at the conference held in a Presbyterian meetinghouse. They took turns speaking to a disappointingly sparse crowd, but the next day saw four hundred people show up and an additional two hundred in the afternoon. The missionaries “had the spirit of speaking,” and the now-packed congregation gave the “best of attention.” News of Joseph’s death arrived two days later, on 9 July, destroying the momentum.[61]

Erastus Snow preached and campaigned in Woodstock, Vermont, where he also was to preside over the conferences, organize the work in the state, and perform “those duties that had been particularly imposed upon [him].”[62] On 11 June he and other electioneers held what was termed a “Jeffersonian Meeting” in the Masonic Hall of Petersborough, New Hampshire. A “mass meeting of the citizens . . . without distinction of sect or party assembled . . . to express their views and feelings touching the political condition of the nation.” A “free expression of feelings” from speakers of various views unfolded, with Erastus Snow, Jonas Livingston, and J. C. Little drafting “resolutions expressive of the views of the meeting.” The next day the assembly met at the “Town House” to hear the resolutions, which included using “all lawful ways and means to endeavor to reform the abuses of trust and power in . . . government” by selecting “independent candidates.” Furthermore, it was resolved that Joseph Smith’s Views rendered “him worthy [of] the suffrages of all free and enlightened people.” After two evenings of “spirited and interesting discussion,” all but five attending the meeting agreed to the resolutions.[63]

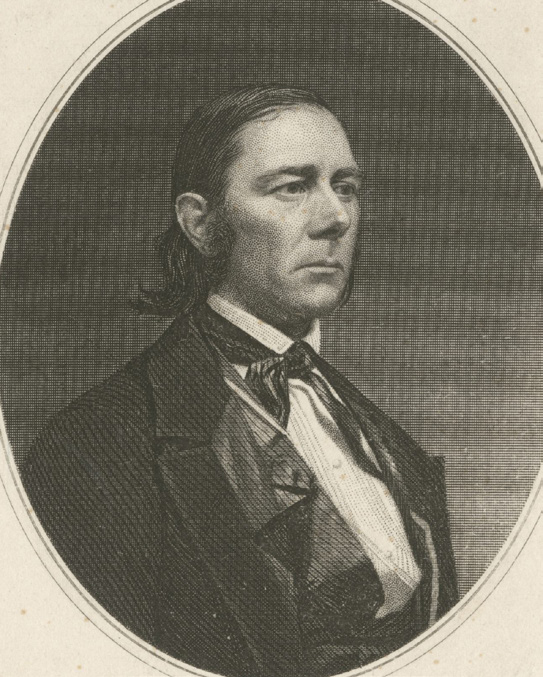

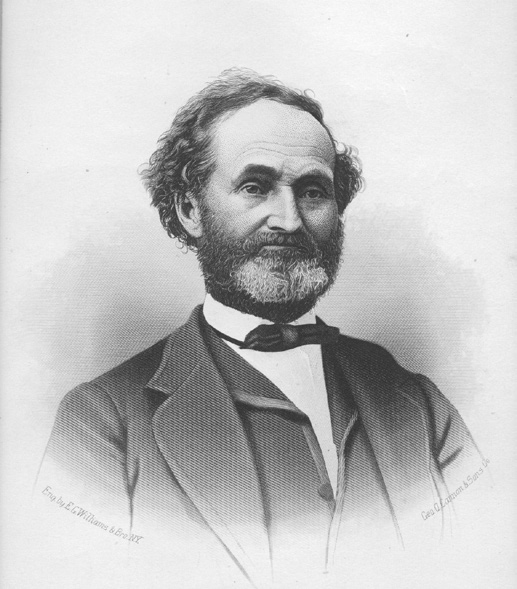

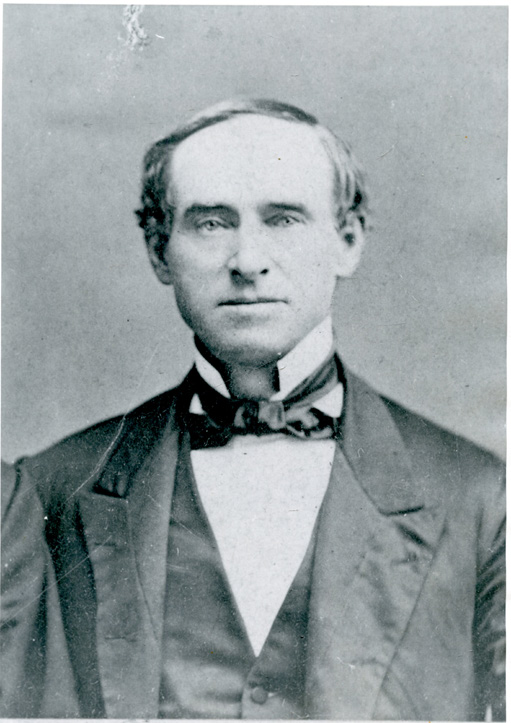

Known as the “wisest man in Nauvoo,” Daniel Spencer led an effective campaign in Massachusetts. Image of undated engraved portrait courtesy of Church History Library.

Known as the “wisest man in Nauvoo,” Daniel Spencer led an effective campaign in Massachusetts. Image of undated engraved portrait courtesy of Church History Library.

Daniel Spencer, who Joseph called the “wisest man in Nauvoo,” was president of the electioneers in his native Massachusetts.[64] He and several other electioneers participated in the scheduled Boston conference of 29–30 June in Franklin Hall. Overseen by Brigham Young and four other apostles, the two days were a mix of religion and politics. The apostles and certain electioneers “gave instruction to the church on religion [and] the policy of government.”[65] On 1 July a massive crowd packed the famed Melodeon to participate in the state convention. Various speeches excited the multitude until a riot broke out in the evening. Despite the presence of apostles, Daniel Spencer chaired the convention’s second day, this time back at Franklin Hall. During the meeting, Spencer and the others planned smaller conferences in each of the state’s ten congressional districts.[66] After the political speeches at the Boston conference and convention, James H. Glines stated, “considerable excitement prevailed throughout the city; very many people were favorably inclined to vote for our candidate for president.”[67] The “good feelings” toward the electioneers’ message continued in the scheduled conference at Salem on 8–9 July.[68]

Mid-Atlantic

In Pennsylvania David D. Yearsley and Edson Whipple led the campaign. They left Nauvoo together and “canvass[ed] that state and present[ed] to the people Joseph Smith’s views on government, and also . . . advocate[0] his candidacy for the presidency of the United States.”[69] Edward Hunter’s Nantmeal Seminary in “Mormon Hollow,” north of Philadelphia, became a headquarters for electioneers. Ezra T. Benson, campaign president for New Jersey, left Nauvoo with John Pack. Along the way and throughout New Jersey, they “preach[ed] the gospel and present[ed] Bro. Joseph [Smith] as being the most suitable man for president.” On 18 June in Salem County, New Jersey, Benson held “a meeting of the friends of Gen. Smith of Nauvoo, Ill., as a candidate for president.” “The friends of Gen. Smith [were] requested to organize in every part of the state immediately and send delegates to the convention at Trenton.” Benson concluded the conference with a “very spirited address.”[70]

In 1844 the West Nantmeal Seminary in “Mormon Hollow,” Pennsylvania, owned by Latter-day Saint convert Edward Hunter, was the informal headquarters of electioneers in the mid-Atlantic states. 2016 photograph by Nora Moulder.

In 1844 the West Nantmeal Seminary in “Mormon Hollow,” Pennsylvania, owned by Latter-day Saint convert Edward Hunter, was the informal headquarters of electioneers in the mid-Atlantic states. 2016 photograph by Nora Moulder.

David S. Hollister preached and politicked on the steamboat Valley Forge as he made his way to Baltimore to attend the Democrat National Convention and prepare for Joseph’s convention. He found the passengers very interested in “national matters,” and together they spent much of the journey reading and discussing Joseph’s Views. Hollister became “a lion among the passengers” and, upon disembarking, received several offers of a coach ride to Baltimore. Arriving between the Whig and Democratic conventions, Hollister, a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, electioneered to all he could “for the promotion of the good cause.”[71]

Charles Wandell was the senior campaign president of New York. Records from other missionaries and The Prophet describe Wandell as busily traversing the state, attending conferences, and organizing the work. Initially arriving in New York City, he lectured on 26 May at the Marion Temperance Hall. Two weeks later he attended a “Jeffersonian Meeting . . . of the friends of General Joseph Smith [that] convened in the Military Hall [on] June 11, 1844.” They resolved to have a conference in “Utica, Oneida County, N.Y., on the 23rd of August.” Wandell instructed “all the friends of GEN. SMITH . . . to organize in every part of the state immediately and send delegates to the convention in Utica.”[72] “Electors favorable to the election of Gen. Smith to the presidency [were to] be selected by his friends in each electoral district of the state and [their names] submit[ted] . . . to the Utica Convention.”[73]

New Jersey campaign president

New Jersey campaign president

Ezra T. Benson (top) and John

Pack (below) held dozens of meetings and distributed thousands of copies of Joseph’s Views. Images are a daguerreotype ca. 1850–60

by Marsena Cannon and an

engraved portrait ca. 1890, respectively. Both images courtesy

of Church History Library.

In an open letter in The Prophet, Wandell wrote that he and Marcellus Bates had arrived to preside, and he instructed missionaries to report their work through the newspaper. Wandell, Bates, and others attended another “Jeffersonian Democracy” meeting in New York City on 17 June. Apostle William Smith was back in town and chaired the meeting, which was “large and enthusiastic.” “In a forcible manner” Smith “show[ed] the necessity” of the campaign, deriding the “two great political parties” to “deafening applause.” Apostle Orson Hyde and then Wandell Wallace both gave strong defenses of Joseph’s campaign, to much acclamation. William H. Miles and David Rogers were chosen as delegates to attend the Baltimore Convention on 13 July. The meeting closed to “nine cheers for Gen. Smith and Sidney Rigdon.”[74] The next week Smith would give another forceful speech in favor of his brother at the well-attended Marion Temperance Hall. Curiously, the papers did not dispatch reporters to these later, larger meetings. Wandell and Bates crisscrossed the state, attending conferences in Cambria on 28–29 June, Genessee on 6 July, and Portage on 14–15 July. At each, Wandell lectured “on the degraded state of [the] country and the importance of the Saints making every effort to usher in the reign of righteousness” with the election of Joseph.[75] The electioneers clearly understood theodemocracy and why their leaders were seeking the prophet’s election.

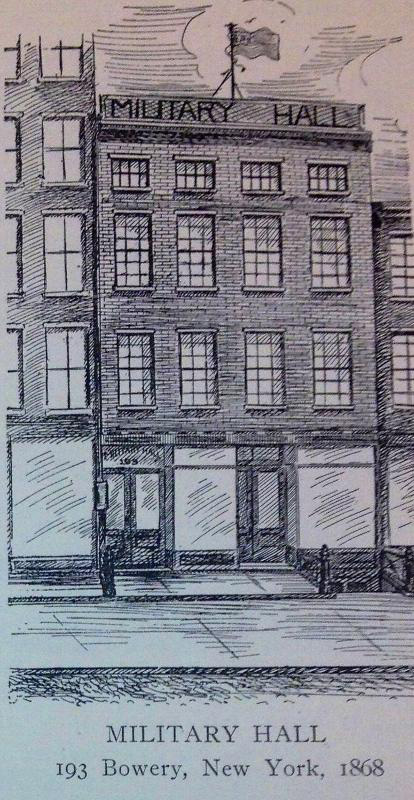

A closer look at the 11 June 1844 meeting, which journalists did attend, reveals bold and determined electioneer missionaries. Held at Military Hall in lower Manhattan, the “Jeffersonian Meeting” included apostles, local Saints, and other New Yorkers. George T. Leach, coeditor of The Prophet, was chair. Although the meeting began with only thirty-four participants, by the time it ended, the building was full. Apostolic brothers Parley and Orson Pratt, along with electioneer J. B. Meynell, forcefully decried Martin Van Buren and Henry Clay while setting forth Joseph’s Views to thunderous applause “mingled with hisses and cries of ‘shut up.’”[76]

Parley P. Pratt delivered the most stinging, and subsequently reported, talk of the evening.

For some years past we have had no government . . . [because] white men have been shot and hung, and negroes burned without trial, judge, or jury; abolitionists have been mobbed and shot; Catholic churches, dwellings, and convents burned, and fifteen thousand American citizens [Latter-day Saints] robbed of millions and driven from a state, and many of them murdered, and this by executive and legislative authority, without shadow of law or justice, and still there is no redress or protection, though years have passed since the perpetration of these horrid crimes: who then shall dare to say there is a government?

Pratt declared the time had come for drastic change. “Except this nation speedily reform and hurl down such men, and put in men who will execute the laws for the just and equal protection of all, [the nation will be destroyed].” As a persecuted minority, the Saints had “no fault to find with the laws or the Constitution of the country.” Rather, their complaint was that they could not “enjoy the benefit of them.” The time had come to stand up for the equal rights of all citizens, for “the Catholics may be the sufferers today, the Mormons tomorrow, the Abolitionists next day, and next the Methodists and Presbyterians. Where is safety if a popular mob must rule and the unpopular must suffer?” For Pratt, American liberty was dying and drastic action was needed: “We must—we will—revolutionize this corrupt and degraded country so as to restore the laws and rights of its citizens, or we must and will perish in the attempt. And it matters not whether with many or with few, had I but ten patriots to associate with me I would either restore the country to its rights or leave it and live with the heathens, or sleep with the dead.” He touted the prophet as “an independent man with American principles, and he has both [the] knowledge and disposition to govern for the benefit and protection of ALL. . . . HE DARE DO IT, EVEN IN THIS AGE.” Pratt’s forceful words, though derided in the newspapers, were a clear signal to the gathered audience—Joseph’s candidacy was serious. The gloves were off.[77]

As a campaign president,

As a campaign president,

Charles W. Wandell feverishly

crisscrossed New York state

attending and speaking at electioneer conferences. Courtesy of the Community of Christ.

The Military Hall in lower

The Military Hall in lower

Manhattan served as the meeting place for many campaign meetings in New York City. Courtesy of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the United States.

Targets of Persecution

Despite the electioneers’ passionate politicking and encouraging successes, some Americans vigorously opposed Joseph’s Views, his candidacy, and his electioneers. Toward the end of the 11 June 1844 Military Hall meeting, “some evil disposed loafer began to play tricks on the gas pipe leading to the room,” resulting in the meeting being “broke[n] up in a very unceremonious manner.”[78] Many accused the electioneers of being beggars and deceivers.[79] Kentuckians told John D. Lee he was not even human but a “different being, . . . one of the fish kind.”[80] People denied shelter to electioneer missionaries simply because they advocated the prophet. Alfred Cordon recorded a typical response by a tavern keeper to a plea for a bed: “The answer was No, No, Joe Smith is a Devil!”[81] Lorenzo H. Hatch was one of several who became seriously ill from constant nocturnal exposure.[82] Jacob Hamblin was so desperate to sleep indoors he even offered what little extra clothing he had for payment, to no avail.[83]

Animosity toward Joseph was strongest in western Illinois, where his influence was the greatest. One man told James Burgess and Alfred Cordon that “if he had power in the country he would not let Smith have one vote and further said if Joe Smith should get elected president, he would go to Africa.” One declared that if “Joe Smith got elected he knew a man that would shoot him . . . , [and] it would be doing good to shoot him, for he was a d--n rascal.” Other harsh remarks proved prescient. In stating that “he would not mind shooting Joe Smith,” one man added that “if there was any chance of him being elected that there was a mob far off that would shoot him.”[84] William L. Watkins took a wagon ride near Warsaw with a man who flatly stated, “Joe Smith will never occupy the presidential seat; before he gains the election he will be killed.”[85]

But political animosity toward Joseph was not just local, and it could even pit Latter-day Saints against their distant families. Dwight Harding is one example. After being baptized by his childhood friend Joseph Holbrook in 1833, Harding joined with the Saints in Kirtland, Far West, and later Nauvoo to the dismay of his family. Technically not an electioneer, he wrote his father in the early summer of 1844 to urge him and other family members and acquaintances to convert to the church and vote for Joseph. He enclosed a copy of Views. His father, Ralph Harding, responded with a stinging rebuke. As for the gift of Views, “Dwight, I don’t thank you for that,” Ralph penned. “The people here aren’t such fools as to vote for Jo Smith for president of these United States.” Then he expressed what others around the nation felt. “I see what you are after,” Ralph accused; “it is for the Mormon[s] to get the power into their own hands for to rule this nation.” He lamented, “I hope that time will never come, but if it should I believe that will be awful work.” In a later letter Ralph further chastised his son: “I must tell you, Dwight, that you have brought much trouble and disgrace to me in my old age.”[86] Throughout Illinois and the nation, many citizens feared Joseph’s gaining political power outside Nauvoo, and some even determined he must die.

For some electioneers, reactions to their message often turned dangerous. A group of men tarred and feathered Eli McGinn.[87] A drunken crowd stoned and injured Levi Jackman and Enoch Burns.[88] Another mob beat Benjamin Brown and his companion Jesse W. Crosby. Brown remembered, “Some of them held me while the rest beat me about the head with their fists; but not being able to bruise me sufficiently in this manner, one of them took off one of my boots, and belabored me about the head with the heel of it, until I was covered with blood.” They then jumped on him with their knees breaking several of his ribs. Brown feigned death. His attackers then scampered away. After Brown found Crosby, the missionaries escaped to a nearby house, only to be attacked again. The mob threatened to “get possession of both of us, after which they purposed to cut off Elder Crosby’s ears, tar and feather us, carry us out into the middle of [the] river, and, after tying stones to our feet, sink us both.” Three times that night Brown and Crosby held the door against the mob.[89]

While electioneering in Marion County, Illinois, David Lewis came face-to-face with a member of the mob that had executed his brother and attempted to kill him at Hawn’s Mill. Lewis recorded that the former Missourian boasted of his participation at the massacre and “seemed for awhile to think as I was alone that he would frighten me.” He “talked very saucy about his being wounded,” to which Lewis responded that “[he] wished it was his neck instead of his leg.” With thoughts of his murdered brother and his own narrow escape, Lewis wrote, “[1] forg[o]t that I was a preacher, for I felt more like fighting than preaching.” However, a crowd had now assembled to hear Lewis. Obviously the “subject of our persecution was uppermost in my mind,” Lewis wrote. “I spoke largely on this subject and pointed my finger at . . . [the Missourian] and said, ‘Th[e]re is one of the actors in this cruelty, persecution, and murder.’ Every eye was turned to him with scorn, and he arose from the congregation and left the room.”[90]

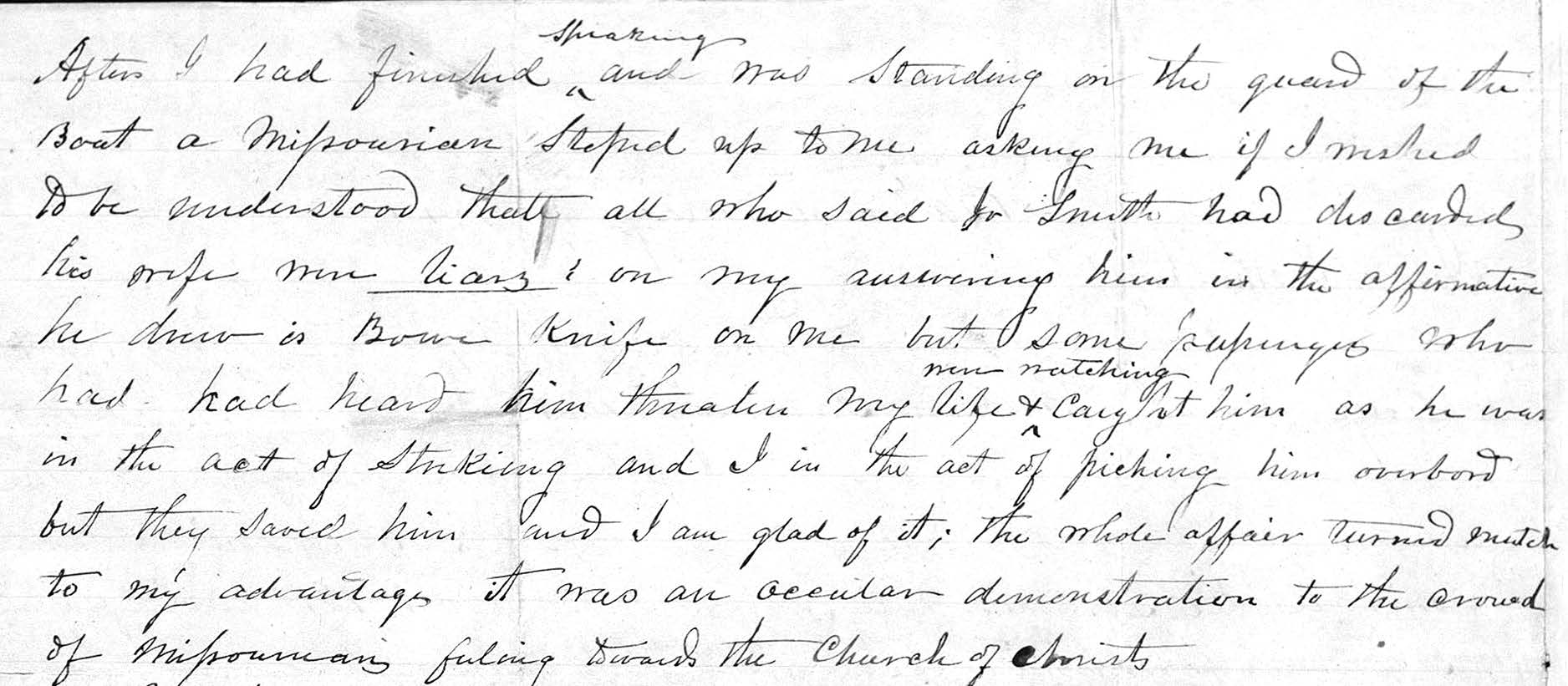

While Joseph Young was preaching in Ohio, a man yelled, “If I hear one say ‘[the] Prophet Joseph Smith,’ damn the Mormon elders,” and threatened to “stain his hands with their blood.” Young pragmatically recorded, “This gave me the understanding that I must be cautious.”[91] Another antagonist threatened George Miller in Kentucky: “If you do not leave this country and put a stop to preaching your religious views and political Mormonism, the negroes are employed to hang you to an apple tree.”[92] A Missourian accosted David S. Hollister on a steamboat when he discovered Hollister was a Latter-day Saint electioneer. The man drew a Bowie knife, and a struggle ensued until passengers broke up the fight.[93] Jacob E. Terry and his companion Theophilus Nixon electioneered on the wharf in Chicago, handing out copies of Joseph’s Views. Terry wrote that a mob led by a former mayor of Chicago “abased us shamefully [and] throw[e]d old tobacco chews and other filth in our faces [and] railed out against the Mormons and against Joseph Smith.” The horde taunted Terry to read Joseph’s Views. As Terry “commenced reading they tore the document to pieces.” Terry called for the city marshal only to receive “more abuse” from him.[94]

Electioneer David S. Hollister’s letter describes his being attacked on a steamboat

Electioneer David S. Hollister’s letter describes his being attacked on a steamboat

by a “Missourian” with a “Bowie Knife” for advocating “Jo Smith.” David Hollister

to Joseph Smith, 9 May 1844. © IRI. Used by permission.

Abraham O. Smoot, president of the work in Tennessee, quickly learned his men would encounter serious opposition. On 18 May he preached at the courthouse in Dresden. Soon after he began, someone fired a pistol at him through one window and “brickbats” crashed through another. Frightened, much of the congregation exited while Smoot assured them that if they stayed they would be protected. He continued to preach while electioneer colleague and local member William Camp guarded the door with a shotgun. Smoot wrote that many stayed while he “dispensed the words of eternal life unto them, which [he] did in as plain and conspicuous a manner as possible for the space of one hour.”[95]

A week later Smoot and twelve other electioneers held a campaign convention in the packed courthouse. This time they came prepared with hickory sticks to defend themselves. Again their enemies interrupted the meeting. A lawyer sat at the front of the congregation and heaped abuse, continually interrupting the proceedings. As the convention ended, around 150 men forced their way into the courthouse and blocked the exits. The leader of the mob, county sheriff M. D. Caldwell, then stood on a bench and exclaimed, “Fellow citizens, you see that these men [electioneers] are come amongst us to raise insurrection and [are] passing [abolition] principles amongst our slaves.”[96] Smoot asked Caldwell what he wanted, to which the sheriff responded, “Blood, [for] you have come here to incite the slaves to kill [their] masters.” When some of the mob moved to attack Smoot, the six-foot-tall, two-hundred-pound wife of William Camp stepped forward, pulled up her sleeves, and roared, “Mr. Caldwell, you dare to touch one of them elders and I will see your heart blood.” One of the mob yelled to “knock her down,” to which the suddenly reticent sheriff responded, “No, Mrs. Camp, they shan’t hurt you.” With Mrs. Camp in the lead, the missionaries exited the building single file, each with a heavy hickory walking stick in his hand.[97] Not to be outdone by his wife, Mr. Camp then knocked the vexatious lawyer to the ground and “kick[ed] him around the courthouse yard.”[98] After the electioneers left, the throng turned on the sheriff, who fled. Caldwell sent a communication the next day to Smoot saying that he could hold meetings in the courthouse again. However, Smoot chose to hold the second day of the convention at a local home to avoid more conflict.[99]

On 1 July 1844, following a two-day church conference, a state convention for Joseph Smith’s “Jeffersonian Democracy” began in Boston. Held in the famous Melodeon concert hall, the convention nominated “General Joseph Smith for President [and] Sidney Rigdon for Vice President.” Seven of the Twelve Apostles were present. Throughout the day the convention, packed to overflowing, “was addressed with much animation and zeal.” During the evening session around 9:30 p.m., feminist-abolitionist Abby Folsom rose and interrupted Brigham Young mid-speech. “The Flea of the Conventions,” as she was derisively known, was becoming infamous in New England for derailing large meetings and protesting for women’s right to be heard. Loudly demanding two minutes, “rowdies” in the gallery chanted, “Hear her, hear her.” The meeting quickly devolved into a cacophony of shouting and yelling. Folsom left, but “a large number of rowdies . . . felt disposed to make [a] disturbance.” It started when one young man stood “and commenced a series of rowdy remarks, [being] encouraged by some mob companions until confusion became general in the gallery.” The police were called, and while trying to arrest the troublemakers, “they were assaulted and beaten badly by a set of young desperadoes.” One received disfiguring cuts to his face. After a prolonged fight, the police cleared the gallery, but the meeting broke up in confusion.[100]

A convention attendee submitted a detailed account to The Prophet. The instigators were “‘Whig young gentlemen’ of this pious, puritanical city,” he wrote. “The well-dressed rowdies of Boston assembled en masse to ‘rout the Mormon humbugs’” out of “nativist” feelings. By this time a rising number of Protestant nativists centered in large northeastern and mid-Atlantic cities were associated with the Whig Party. Conversely, Latter-day Saints and Catholics, both immigrant laden, generally joined with Democrats. Whig influence and nativism were common threads in the Philadelphia Bible Riots, the Melodeon riot, and the forthcoming assassination of the prophet (all in the summer of 1844). The author demanded: “Must we forever have to hold up the damning effects of bygone persecutions, Roman Catholic persecutions . . . ? Must we rake up the ashes of the convent [burned a month before in Philadelphia] to shake on the heads of the ‘Natives’ . . . [or remember the] Mormons who have been robbed, whipped, tarred and feathered, hunted, and shot down like mad dogs for daring to worship God after the dictates of their conscience in this enlightened age, in this land of Liberty?” He declared, “There is not on God’s footstool a set of whelps more contemptible than our Boston, . . . well-dressed rowdies, vain, empty, brainless, shameless monkeys.”[101] To avoid another fracas, the conference moved to Franklin Hall for its second day.

In the face of persecution, the electioneers’ unstinting efforts garnered national attention. Partisan presses blistered the campaign and its electioneers, trying to pin the Saints on the other political party. Even so, the campaign was beginning to create interest, and by the end of June it was building momentum. The electioneers were having surprising success in some sectors and awakening strong opposition in others. The Whigs had selected Henry Clay as their candidate, while the Democrats nominated dark horse candidate James Polk. Like the nascent anti-slavery Liberty Party, Joseph Smith’s “Jeffersonian Democracy” was gaining support at the fringes—and that support was growing. Church leaders and electioneers alike confidently worked at an exhausting pace, expecting further help from heaven.

If Joseph was not elected directly, they believed, at the least they could control enough votes for one of the parties, probably the Democrats, to offer a deal of protection—similar to how the Catholics were ensconced within the Democratic Party. What the Saints did not yet know was that their envoy to the Democratic National Convention, David S. Hollister, had met with “little success.” On 26 June 1844, Hollister reported that his negotiations had been “a series of disappointments” and that he had turned to preparing for the Saints’ own national convention. Such disappointments were but the slightest foretaste of utter devastation to come.

* * *

Electioneer Experience: John Horner. Three years after nineteen-year-old John Horner was baptized by Erastus Snow in 1840, the young farmer moved to Nauvoo, where he soon met Joseph. At the 9 April 1844 special conference meeting, Horner was “appointed to electioneer . . . [and] endeavor to elect the prophet president.” Before leaving for his assignment in his home state of New Jersey, he ordered a thousand copies of Views to distribute. One night in early July, “while speaking to a full house of attentive listeners,” he ended his political lecture by inviting “all to speak who wished to.” Horner most likely expected some positive comments from the enthusiastic following. What he heard instead shocked him and stunned the audience. A gentleman arose and, turning to Horner, declared, “I have one reason to give why Joseph Smith can never be president of the United States; my paper, which I received from Philadelphia this afternoon, says that he was murdered in Carthage Jail, on June 27th.” Immediate sober silence “reigned” in the house. Slowly “the gathering quietly dispersed,” but not Horner. The news had shaken him to his core. “The grief and sadness” of his heart, he wrote, “was beyond the power of man to estimate.”[102]

Notes

[1] “Increase of Mormonism,” Pittsburgh Morning Post, 8 June 1844, 1.

[2] “Mormon Tragedy: Death of Joe and Hyrum Smith,” Niles’ National Register, 13 July 1844, 1.

[3] George Miller, “Correspondence,” Northern Islander, 6 September 1855, 3.

[4] Rogers, Reminiscences and Diary, 22–23 June 1844, 49.

[5] Lyman, Journal, 25 June 1844, 6:8–9.

[6] G. A. Smith, “History,” 5.

[7] See Jesse Wentworth Crosby, Autobiography, 12; and Crosby, History and Journal, 25–26 May 1844.

[8] “Daily Mercantile Courier,” Buffalo Courier, 2 May 1844, 2.

[9] Sudweeks, “Biography of David and Mary Savage,” 4.

[10] The spring and summer of 1844 was known as the “Great Flood” in the Midwest. It remains the largest recorded flood of the upper Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Beginning in late April, rain fell for six consecutive weeks. Several journals note the incredible amount of rain that fell. Some examples are James Burgess, Journal, 6–8, 10, and 13 May; Jackman, “Short Sketch,” 24; and Watkins, “Brief History,” 2.

[11] Boyle, Autobiography and Diary, 10.

[12] Franklin D. Richards, Journal No. 2, 1 June 1844, 4.

[13] See Burgess, Journal, 30 May 1844.

[14] Boyle, Autobiography and Diary, 6.

[15] Holt, “Autobiographical Sketch,” 5.

[16] Hunt, Diary, 1–5.

[17] Pettegrew, “History of David Pettegrew,” 190.

[18] See Little, “Biography of William Rufus Rogers Stowell,” 22–23.

[19] See Whipple, Record Books, 1:2.

[20] Tracy, Reminiscences and Diary, 27.

[21] Barney, Autobiography, 2.

[22] See Jackman, “Short Sketch,” 23.

[23] See William Hyde, Journal, 29–30 June 1844.

[24] They were Pleasant Ewell, George P. Dykes, Franklin D. Richards, Crandell Dunn, Joseph A. Stratton, and George Wallace.

[25] Holbrook, “Life of Joseph Holbrook,” 60.

[26] Duke, Reminiscences and Diary, 2.

[27] Duke, Reminiscences and Diary, 45.

[28] Franklin D. Richards, Journal No. 2, 8.

[29] Sudweeks, “David and Mary Savage,” 4.

[30] See Riser, “Unfinished Life Story,” 7; Riser, Reminiscences and Diary, 9–10; and Watkins, “Brief History,” 1.

[31] See Dunn, “History and Travels,” 1:41–46.

[32] See Jacob, Record of Norton Jacob, 5.

[33] Cordon, Journal and Travels, 4:4 (27 June 1844); and Burgess, Journal, 5 May–27 June 1844.

[34] See Lee, Journal, 2.

[35] Burgess, Journal, 7 May 1844. See Cordon, Journal and Travels, 3:183 (7 May 1844).

[36] George A. Smith, “History,” 2.

[37] Cordon, Journal and Travels, 3:200 (26 May 1844); and Burgess, Journal, 25–26 May 1844.

[38] “Chicago, Ill., May 27, 1844,” Times and Seasons, 1 August 1844, 606.

[39] Terry, Journal, 29 May–13 June 1844.

[40] See Lyman, Journal, 1–11.

[41] Little, “Biography of William Rufus Rogers Stowell,” 22.

[42] Snow, Journal, 48–49.

[43] Franklin D. Richards, Journal No. 2, p. 5.

[44] Snow, Journal, 48–50.

[45] George A. Smith, “History,” 8.

[46] Duke, Reminiscences and Diary, 42.

[47] The assignments are recorded in the back of Rich, Journal, 14, 16.

[48] Jacob, Reminiscence and Journal, 6.

[49] See Rich, Journal, 14 June and 2, 3, 6 July 1844 (pp. 7, 9–10).

[50] Lee, Journal, 13.

[51] Lee, Mormonism Unveiled, 149; original capitalization preserved.

[52] George Miller, “Correspondence,” Northern Islander, 6 September 1855, 4.

[53] Watkins, “Brief History,” 2.

[54] Holbrook, Life of Joseph Holbrook, 60.

[55] Smoot, “Day Book,” 2–3.

[56] Alphonso Young, letter to the editor, Times and Seasons, 1 December 1844, 733.

[57] Riley, Diary, 22 June 1844.

[58] Smoot, “Day Book,” 2–5. See Thomas, “Historical Sketch,” 31–32.

[59] See Boyle, Autobiography and Diary, 6–7.

[60] See Thomas, “Sketch and Genealogy of the Thomas’ Families,” 30–38.

[61] Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 2:416–20.

[62] Erastus Snow, Journals, 48–49.

[63] “Jefferson Meeting at Petersborough, N. H.,” The Prophet, 29 June 1844, 2.

[64] Stewart, Histories of Daniel Spencer, 3.

[65] Kimball, Diaries of Heber C. Kimball, 3:70.

[66] See “At a Special Conference of Elders Held at Franklin Hall, Boston July 2nd, 1844,” The Prophet, 6 July 1844, 3.

[67] Glines, Reminiscences and Diary, 39.

[68] Kimball, Diaries of Heber C. Kimball, 3:71.

[69] Whipple, Diary, 1.

[70] Benson, “Ezra Taft Benson, I: An Autobiography,” 214; and “Jeffersonian Meeting at Salem, N. J.,” The Prophet, 29 June 1844, 2.

[71] David Sprague Hollister to Joseph Smith, 9 May 1844.

[72] “A Meeting of the Friends of General Joseph Smith of Nauvoo, Ill,” The Prophet, 1 June 1844, 2.

[73] “Jeffersonian Meeting at Salem, N. J.,” The Prophet, 29 June 1844, 2.

[74] William Smith and William H. Miles, “Great Jeffersonian Meeting,” The Prophet, 22 June 1844, 2–3.

[75] The Prophet, 1 June 1844, 1, 4; 20 July 1844, 2–3; and 3 August 1844, 3. The quotation is from the 20 July issue.

[76] “Great Mass Meeting,” New York Herald, 12 June 1844, 4.

[77] “Jeffersonian Meeting,” The Prophet, 15 June 1844, 3; all-caps style preserved.

[78] “Great Mass Meeting,” New York Herald, 12 June 1844, 4.

[79] See Little, Jacob Hamblin, 17.

[80] Lee, Journal, 12.

[81] Cordon, Journal and Travels, 3:207 (30 May 1844); capitalization preserved.

[82] See Hatch, Biography of Lorenzo Hill Hatch, 57–58.

[83] See Hamblin, Record of the Life of Jacob Hamblin, 103.

[84] Burgess, Journal, 7 May 1844.

[85] Watkins, “Brief History,” 1.

[86] Ralph Harding to Dwight Harding, 22 August 1844 and 3 March 1846. Thanks to Benjamin Park for pointing me to the 22 August letter in 2016.

[87] See Cordon, Journal and Travels, 4:3 (17 June 1844).

[88] See Jackman, “Short Sketch,” 21.

[89] Brown, Testimonies for the Truth, 22–23.

[90] Lewis, Autobiography, 30.

[91] Joseph Young, Diaries, 4–5.

[92] Miller, Correspondence of Bishop George Miller, 20–21.

[93] See David Sprague Hollister to Joseph Smith, 9 May 1844.

[94] Terry, Journal, 26 May 1844.

[95] Smoot, “Day Book,” 18 May 1844. See Smoot, “Early Experience,” 22–23.

[96] Smoot, “Day Book,” 25 May 1844.

[97] Thomas, “Sketch and Genealogy of the Thomas’ Families,” 32–33.

[98] Smoot, “Early Experience,” 23.

[99] Smoot, “Day Book,” 25 May 1844.

[100] Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff, Fourth President of the Church, 1 July 1844, 2:415. See Boston Mail, 2 July 1844, for another report of the incident.

[101] “Whigs of Boston,” The Prophet, 13 July 1844, 2.

[102] Horner, “Adventures of a Pioneer,” 214–15.