The “Hike”

Fear not, I am with thee; oh, be not dismayed,

For I am thy God and will still give thee aid.

—Robert Keen, “How Firm a Foundation”

The geography of the Manila Bay is important to understanding our unfolding story. About three miles off the tip of the Bataan Peninsula is the small island of Corregidor, a heavily fortified island with guns that guarded access to Manila Bay. It was also the location of the bombproof Malinta Tunnel with its honeycombed maze of reinforced concrete laterals and cavernous ventilated shafts used for hospital wards, offices, and storage. With the retreat from Manila, Corregidor had become the command center for General MacArthur and, following his departure, General Wainwright.

Corregidor’s strategic significance was that its guns blocked free access to Manila Bay. For safe access to Manila Bay, the Japanese needed to control Corregidor. Corregidor was best captured from the southern tip of the Bataan Peninsula, which was exactly where Hamblin, Brown, Davey, and the other surrendering US troops were now clustered.[1]

A few weeks before the US troops surrendered, Japanese general Homma and his staff had developed a plan to evacuate the prisoners they expected to capture on the Bataan Peninsula. The plan provided for the prisoners to be moved from Bataan to a prison camp some seventy miles north in central Luzon. The plan grossly underestimated the number of surrendering soldiers, the soldiers’ health, and the complications of moving the prisoners north to camps at the same time the Japanese infantry was moving south for an assault on Corregidor.

Upon the surrender of the Filipino and American forces, it became obvious that the evacuation plan was wildly out of touch with the reality. While the Japanese had expected about forty thousand prisoners, the actual number was closer to a hundred thousand, including civilians.[2] Moreover, the troops surrendering were concentrated in southern Bataan, exactly where General Homma needed to move his troops to launch the final assault on Corregidor.

General Homma’s initial attacks on Bataan had not been successful, and he was now months behind schedule, throwing off Japan’s overall timetable for its Far East campaign and putting him under growing criticism in Tokyo. Consequently, General Homma’s paramount objective was to get the surrendering troops out of the way of his 14th Army, which was marching south.[3] He would take no time to adjust the flawed evacuation plan to actual circumstances; instead, he ordered commanders and soldiers to do the impossible. The result was a catastrophe of torture, murder, sickness, suffering, and the unnecessary deaths of thousands of surrendering soldiers.[4]

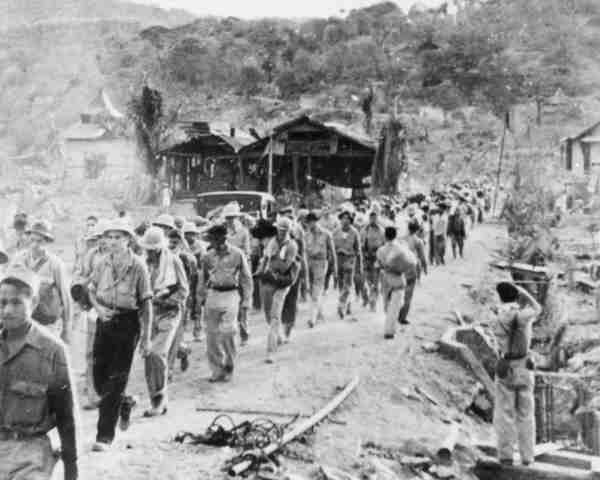

Soldiers surrendered in various locations in Bataan and, after being searched, were organized in groups and marched north. The forced march on foot northward along the East Road to San Fernando became known as the “Bataan Death March.” However, with characteristic understatement, the prisoners often simply called it the “hike.”[5] Depending on where they surrendered, prisoners walked for five to twelve days—a distance of a few miles to as many as sixty miles—in the tropical sun with little or no food or water.[6]

The guards knew they could be punished or severely reprimanded if a POW escaped or if they did not arrive at the appointed place on time. However, there was no punishment or reprimand for a dead POW. Accordingly, the guards were merciless in prodding the prisoners with their bayonets to speed up the pace. By relieving and replacing the guards at short intervals, the Japanese always had rested guards to step up the pace of the weary, sick, and starving POWs.[7]

POWs who could not keep pace were killed. If a prisoner fell down or fell behind, sometimes the guards would shoot them, but to save bullets often used their bayonets, driving the blade deep into the abdomen and making three twists in the shape of a Z to scramble the bowels, leaving the prisoner to die.[8] The Japanese guards were practiced and proficient in the use of their bayonets. Davey wryly noted, “It is amazing how much strength you get to carry on when suddenly someone in front of you falls out and pulls over to the side and the Jap just shoots him and he falls to the side of the road. I think about every hundred feet there was at least one Filipino or American soldier that had been killed in this manner.”[9]

When the beleaguered prisoners stopped for what they hoped would be a rest or water break, what they often found was only more torture. The Japanese guards commonly made prisoners stand or sit for hours at a time in the hot sun (the “sun treatment”) or had them rest near pools of clean artesian water but killed anyone who broke ranks to drink.[10]

Of his experience on the Bataan Death March, Orland Hamblin wrote, “Many were already weak from sickness and hunger. Some had been on the front lines with very little relief for four months, so it was inevitable that many would fall by the roadside from exhaustion. We were marched out in groups of a few hundred each. Before the last group had arrived at the prison camp, . . . several thousand had died, either shot or bayoneted by the impatient and cruel [Japanese guards]. The civilians who had followed us onto the peninsula were herded out with the rest like cattle; old and young alike, making a scene not soon to be forgotten.”[11]

American POWs on the Bataan Death March. Courtesy of the United States Air Force National Museum.

American POWs on the Bataan Death March. Courtesy of the United States Air Force National Museum.

For many Filipino civilians, most of whom were Catholics, the march must have seemed a horrifically real passion play. Hamblin records that when they passed through towns, Filipino civilians lined the sides of the road, many hoping to get word of their own sons and husbands who were in Bataan, but also helping the prisoners along the march. They hid cans of water in bushes and threw rice balls and cookies into the columns. Children ran along handing fruit and cassava cakes to the prisoners. The good deeds, however, came with consequences. The Japanese guards often beat or took shots at the local Filipinos. A farmer and his wife were burned at the stake for aiding the prisoners. Further, a young, pregnant Filipino woman who had thrown cassava cakes to the prisoners was bayoneted through her womb.[12]

Eventually, those who survived the hike to San Fernando were then packed into cramped and poorly ventilated boxcars and taken by train about twenty miles north to Capas. By this time, many of the prisoners suffered from dysentery and other diseases. The result was an overpowering stench in the cars, which had temperatures exceeding 100 degrees. Weak from the march and the lack of food and water, as well as suffering various diseases, some died standing up in the boxcars. Survivors were then marched from the rail terminal another ten miles to Camp O’Donnell.[13]

The exact number who took part in or who died on the death march is impossible to know, but about twelve thousand Americans and as many as sixty-five thousand Filipinos began the sixty-five-mile march from the Bataan Peninsula to San Fernando. Estimates vary widely, but a median guess is that around 750 Americans and more than five thousand Filipinos died on the march.[14] The Japanese guards were even more vicious in their treatment of the Filipinos than the Americans. The causes of death were many, from malaria and dysentery to starvation to sheer exhaustion and what can only be described as torture and murder. Sadly, Brown and Hamblin’s units, the 515th and the 200th, were well represented on the Death March.[15]

Despite the cruelty and suffering—and with luck, courage, and an occasional miracle—Brown, Hamblin, Davey, and other Latter-day Saint POWs survived the ordeal.

Notes

[1] Morton, Fall of the Philippines, 471; Shively, Profiles in Survival, 1, 50–51.

[2] Shively, Profiles in Survival, 53–54.

[3] Hamblin, “My Experience,” 8; Shively, Profiles in Survival, 50–51.

[4] After the war, General Homma was tried, convicted, and executed for war crimes related to the Bataan Death March and the treatment of prisoners at the Camp O’Donnell and Cabanatuan camps in the Philippines. Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese, 365.

[5] Sides, Ghost Soldiers, 91.

[6] Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 114; see Garner, Unwavering Valor, 71–72 (estimates fifty-five miles). Other POWs estimate the distance as about one hundred miles, but those estimates likely include the twenty-five-mile train ride. Hamblin, “My Experience,” 8; Robert G. Davey, “Last Talk,” 1.

[7] Jacobsen, We Refused to Die, 89; Hamblin, “My Experience,” 8.

[8] Sides, Ghost Soldiers, 89; Shively, Profiles in Survival, 56–70; Davey, “Last Talk,” 2.

[9] Davey, “Last Talk,” 1–2; “Faith Sustains Interned Mormon Captain,” Deseret News, March 24, 1945, 7 and 16.

[10] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 63–65.

[11] Hamblin, “My Experience,” 8.

[12] Hamblin, 9; Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 67; Shively, Profiles in Survival, 63.

[13] Shively, Profiles in Survival, 70–71.

[14] Shively, 51; Sides, Ghost Soldiers, 90; Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 73; see also Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese, 80 (no one really knows how many).

[15] The New Mexico National Guard maintains a memorial and museum for the Bataan Death March in Santa Fe, New Mexico. There is also a Bataan Memorial Park in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and a Bataan Death March Statue and Walkway at the Veterans Memorial Park in Las Cruces, New Mexico.