The Easy Life in the Philippines

Choose the right! There is peace in righteous doing.

Choose the right! There’s safety for the soul.

—Joseph L. Townsend, “Choose the Right”

After sailing some seven thousand miles across the Pacific, the troop transport ships entered the South China Sea, passed by a line of tropical islands making up much of the Philippines archipelago, and finally sailed into Manila Bay. As the ships entered the bay, the soldiers saw to the left the fortress island of Corregidor guarding the entrance to the bay. Beyond Corregidor was the large, green, mountainous landmass of the Bataan peninsula, areas with which many would later become intimately familiar. But as they entered the bay, their focus was on the famous deep-water Manila harbor ahead and to the right, then teeming with ships and boats of every kind.

Many of these Latter-day Saint soldiers had lived relatively isolated lives in small rural communities. The sight of Manila would have been a very new experience—a large, tropical city teeming with people and all else that accompanies a military buildup, and, of course, the oppressive humidity. The Philippines is located just a few degrees above the equator, so the days were invariably the same all year—scorching hot and humid. From here on, everything that happened in their lives in the Philippines happened in this oppressive tropical heat.

After disembarking, Brown and Hamblin and the other soldiers of 200th were loaded into trucks for the trip to Fort Stotsenburg, seventy-five miles north of Manila. From the trucks, these new arrivals saw the wide-eyed stares of curious Filipino children watching the huge American convoy roll north through Manila. Once outside the city, they saw rice paddies and banana trees on each side of the road, green mountains in the distance to the east and west, carabao-drawn carts tended by dark-skinned farmers with strange hats, and bamboo homes built on stilts—all new and curious scenes for these young men. Hamblin described the scene: “Everything was strange—strange sights and strange odors. The [carabao], which is their beast of burden, were everywhere, the little one-horse carts drawn by small horses resembling the Shetland, their carts were called caramotas. . . . We saw many bamboo houses built up off the ground on stilts on account of the water and razor back hogs were seen running around under the houses. These, along with their chickens and other fowls and animals, added to the peculiar odor.”[1]

After a few hours, the soldiers arrived at Fort Stotsenburg, an old cavalry post located next to Clark Field. The 200th Coast Artillery Regiment was charged with guarding Clark Field and its fleet of bombers and fighters, which were key to General MacArthur’s Pacific strategy. They had some challenges. Much of the WWI-vintage equipment they had trained with at Fort Bliss in Texas was defective and had been abandoned at Fort Bliss. Typical of the snafus in this buildup, the rejected equipment they had abandoned at Fort Bliss had nevertheless been broken down, loaded up, and shipped to the Philippines anyway, and after the ocean voyage, the equipment arrived in the Philippines in even worse condition. Parts were missing or damaged, replacement parts were unusable, and some searchlights were broken and useless.[2] Using the artillery equipment that did work, they practiced ranging, fusing, and loading, but never actually fired the guns because of the shortage of ammunition. They mostly practiced spotting aircraft with the spotlights and radar that weren’t broken.

Notwithstanding these mobilization problems, the Philippines was an easy and comfortable post for a young soldier. Days started at 0700 (7 a.m.) and ended with a siesta after lunch. Living costs were cheap, and local domestic help was inexpensive and available. Their barracks would likely have been in a sawali, a wooden building on stilts.[3]

These Latter-day Saint soldiers were now thousands of miles away from their families and the religious culture in which they had been raised. They found themselves in a new, exotic location with plenty of bars, clubs, and entertainment of the kind that thrives on soldiers, especially in nearby Manila.[4]

Excursions into Manila, a bustling Asian city teeming with activity and seductive vices, were an exciting event for young soldiers. Despite the enticing wickedness of peacetime Manila, it appears these Latter-day Saint soldiers generally chose wisely. Gene Jacobsen, a Latter-day Saint soldier from Montpelier, Idaho, came to the Philippines earlier as part of the 20th Pursuit Squadron of the Army Air Corps based at Nichols Field just south of Manila. He later wrote of the abundance of alcohol and prostitutes he encountered on his first trip to Manila and his decision to walk away from it.[5] Private Franklin East from Arizona, who at the time was recovering in a hospital from a surgery and who was part of the Fifth Air Base group, wrote of his disgust with soldiers suffering from venereal disease and his gratitude for his church’s standards.[6]

In one of Brown’s last letters home, he wrote about his trips into Manila. Through Major Schurtz, Brown’s commanding officer and an accomplished musician, Brown and some other soldiers had been invited by the university in Manila to join with the university’s chorus in presenting Handel’s Messiah for Christmas. Brown went to Manila to rehearse with the university choir.[7] While there were no organized church services for Latter-day Saints, Brown, Keeler, and Hamblin, and maybe Allred and Bloomfield as well, attended the religious services conducted by the chaplain and informally met together frequently.

Notwithstanding the generally pleasant circumstances of their posting, it turned out to be a tragic time for Hamblin. On November 15, while sitting in the mess hall after dinner, he was handed a cablegram from his sister that read, “Father not expected to live. Struck by plane at Luke Field.” His father, Don Carlos Hamblin, had been working at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona and was accidently struck by the wing of a plane. The following morning, another cable arrived informing him that his father had passed away. Hamblin and his father were close, and the news of his death was painful.

Holding these cablegrams, Hamblin thought back to the day he had left his home for Fort Bliss. Hamblin had been the only son in a family of nine girls until a baby brother was born, and he was the pride of his father’s heart. When he had left Farmington on a bus for Fort Bliss, his father had walked with him to the bus depot. It had been a difficult parting, but Hamblin and his father were so close that not a lot needed to be said. His father’s parting words had been simply “Be good, son.”

Far from home and his family, Hamblin struggled with the loss of his “dear father and counselor.” Hamblin later received some letters his father had written to him before he died, which, while gratefully received and treasured, made him feel the loss even more deeply. He “sought comfort and solace through prayer to my Heavenly Father, which gave me strength to carry on.”[8] With his father dead and his mother in need of comfort and financial support, Hamblin began arranging for a family hardship discharge.

Circumstances, however, would change. Brown would not sing in Handel’s Messiah at Christmas that year, and the processing of Hamblin’s discharge would never be completed.

The convoy with the Fifth Air Base group from Salt Lake City arrived in Manila a few days later on November 20, 1941, Thanksgiving Day; the men were temporarily bivouacked in tents at nearby Fort McKinley. That afternoon they received a Thanksgiving dinner of wieners and sauerkraut with canned peaches for dessert, a meal that was something of a disappointment at the time. While the soldiers had no reason to do so at that time, many of those soldiers would nevertheless later make such a meal a subject of their dreams.[9]

Luzon, located at the northern end of the Philippine archipelago, is the largest and most populous island in the Philippines. It is home to Manila, the country’s largest and most important city and one of Asia’s most famous deep-water harbors, as well as Clark Field, then the principal US air base in Asia. Located about forty miles northwest of Manila, Clark Field was originally intended as the principal base for the B-17 heavy bombers that were key to General MacArthur’s strategy. General MacArthur later realized that Clark Field was within the reach of Japanese bombers flying from bases in Taiwan (Formosa), and the planes were vulnerable to attack. However, the island of Mindanao, located at the southern end of the archipelago, was beyond the reach of those Japanese bombers. That island was home to a large Del Monte pineapple plantation located next to a large pasture used for cattle grazing. That pasture also happened to be a natural runway for heavy bombers. In November 1941 General MacArthur ordered the construction of a new base for heavy bombers at the Del Monte site.[10] The Fifth Air Base Squadron was assigned the task of constructing this field and preparing to receive these B-17 bombers.[11]

On November 30 the Fifth Air Base group boarded an interisland craft, the Legaspi, which took them on an overnight voyage to Bugo, a small port barrio on the Mindanao coast whose principal industry was a large Del Monte cannery. A few miles inland were thousands of acres of pineapple fields and the pasture that would become the Del Monte Airfield.

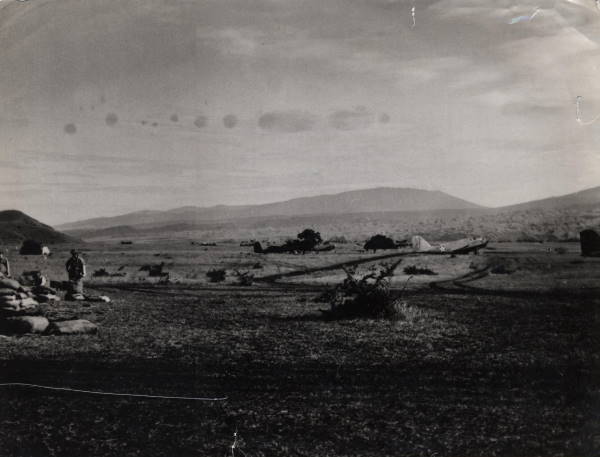

Del Monte Airfield on Mindanao Island in late 1941. The BenHaven Archives. Courtesy of Walter J. Regehr.

Del Monte Airfield on Mindanao Island in late 1941. The BenHaven Archives. Courtesy of Walter J. Regehr.

It was an ideal location. The ground under the sod was hard and would hold up even in wet weather. No grading was required; they just had to cut down the grass. A tractor mower was found, and the farmers in the squadron took over, a group that likely included some of the Latter-day Saint farm boys. There was also all the work of setting up the camp tents, a mess tent, a field kitchen, and then more permanent barracks and all the other facilities needed to sustain a large group of men, as well as the gun emplacements and the structures (revetments) to protect the airplanes.[12] The Fifth Air Base group was later joined by 440th and 701st Ordnance Companies of the 19th Bombardment Group at the Del Monte Airfield. This added at least one additional Latter-day Saint soldier, Theodore Hippler, a private in the 440th from Bloomfield, New Mexico, to the group of Latter-day Saint servicemen at Del Monte.[13]

At forty years of age, Staff Sergeant Nels Hansen was older than most of the other Latter-day Saint air corpsmen; before the war, he had served two missions, including one to the Central States Mission. The family had moved around, and when he enlisted, Hansen was living in Weiser, Idaho. He had brought with him copies of the Church’s scriptures (the Bible, the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price), along with five Deseret Sunday School Song Books and a copy of Added Upon, by Nephi Anderson, a then popular novel among Latter-day Saints about our eternal journey based on Church teachings. With this gospel library and Hansen’s leadership, these Latter-day Saint soldiers formed a Sunday School at Del Monte with regular meetings each Sunday. They had about twenty participants.[14]

This was a busy time for these air corpsmen, with much to be done to construct the airfield and related facilities. Many of the newest B-17Ds of the Seventh Bombardment Group, which was to be stationed at Del Monte, were already on their way from the mainland. However, the grand plans for Del Monte Airfield and the Seventh Bombardment Group were not to be.

Notes

[1] Hamblin, “My Experience,” 3.

[2] Cave, Beyond Courage, 45, 53–54, 8. See also Morton, Fall of the Philippines, 45.

[3] Lukacs, Escape from Davao, 9; Shively, Profiles in Survival, 195–96; Cave, Beyond Courage, 45–51; Gene S. Jacobsen, We Refused to Die: My Time as a Prisoner of War in Bataan and Japan, 1942–1945 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2004), 42–51; see also Hamblin, “My Experience,” 3.

[4] See Shively, Profiles in Survival, 195–96; Jacobsen, We Refused to Die, 46–47 (regarding the prevalence of prostitutes and alcohol).

[5] See Jacobsen, We Refused to Die, 46–47. Jacobsen came to the Philippines nearly a year earlier in November 1940. Although Jacobsen was never at Dapecol, his memoir of his POW experiences is a valuable source of additional insight into the experience of a Latter-day Saint POW in the Philippines.

[6] East, “Army Life,” 8.

[7] Nelle B. Zundel, “George Robin (Bobby) Brown,” in Brown, Alma Platte Spilsbury, 297; Call, “Latter-day Saint Servicemen,” 105–7.

[8] Hamblin, “My Experience,” 3–4.

[9] Christensen, “My Life History,” 5; Raymond C. Heimbuch, I’m One of the Lucky Ones: I Came Home Alive (Crete, NE: Dageforde Printing, 2003), 32; Hayes Bolitho, “The Hayes Bolitho Japanese Story, Parts 1–6,” Hawkins (Texas) Holly Lake Gazette, a biweekly online newspaper, September 26, 2009–February 13, 2010, Part 1 (accessible at http://

[10] Morton, Fall of the Philippines, 43; Burton, Fortnight of Infamy, 63.

[11] See Christensen, “My Life Story,” 5; Heimbuch, Lucky Ones, 26, 33–34.

[12] Burton, Fortnight of Infamy, 63; Bolitho, “Japanese Story,” part 2 (October 10, 2009).

[13] Clark and Kowallis, “Fate of the Davao Penal Colony,” 120.

[14] Ashton, “Spirit of Love,” 175.