Joseph Smith’s Biblical Antiquity

Kent P. Jackson

Kent P. Jackson, “Joseph Smith's Biblical Antiquity,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 165–93.

Kent P. Jackson was a professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this was written.

Most of Joseph Smith’s career as Mormonism’s founding prophet was related in some way to the Bible. The simplest explanation for this is that the Bible contains the record of God’s dealings with people anciently, and Joseph Smith saw his career as the renewal and continuation of that work in modern times. For him, the key term that described his work was restoration, a word that he and his followers adopted to identify early Mormonism in general. Mormonism would be the restoration—the restoration of truth that God had revealed since the beginning of human history, the restoration of the ancient authority to speak anew in God’s name, and the restoration of God’s ancient church to represent his will on earth. Joseph Smith said, “It is necessary in the ushering in of the dispensation of the fulness of times; which dispensation is now beginning to usher in, that a whole, and complete, and perfect union, and welding together of dispensations, and keys, and powers, and glories should take place, and be revealed, from the days of Adam even to the present time.”[1] It would be, in the words of a favorite Mormon quote from the New Testament, the “restitution of all things, which God hath spoken by the mouth of all his holy prophets since the world began.”[2] And all of it would center on the Bible as the revealed precursor and predecessor. Joseph Smith and his ministry would be the next chapter of biblical events.

Much of Joseph Smith’s exposure to the ancient world came through his contact with the Bible. But his relationship with it was unlike that of others of his generation. It was interactive, not static, and it was not at all one-directional. I have argued elsewhere that for Joseph Smith, a key issue of his view toward the Bible was authority: the biblical text was not an ultimate source of authority but a means to a greater source—the authority of revelation which he believed he received from God.[3]

All early Latter-day Saints were converts from other Christian persuasions, and most had been deeply religious before they embraced the Mormon message. They often found in Mormonism familiar teachings about the basic Christian principles that they had held dear in their previous denominations. These would include a literal reading of the stories in the Bible and a belief in the saving work of Jesus Christ with faith, repentance, redemption from sin, and eternal life. Yet beyond such fundamentals, much of Joseph Smith’s teaching seemed strangely disconnected from the Christianity of his time and place, and he himself seemed not to care much about what other Christians believed. Moreover, although at least some early Latter-day Saints knew of the popular Bible commentaries of the day—articles in Mormon periodicals make reference to them[4]—Joseph Smith’s biblical interpretations seem to show no influence from the common views expressed in them. Yet he maintained, perhaps paradoxically, “We believe nothing, but what is to be found in this book.” Indeed, “in it the ‘Mormon’ faith is to be found.”[5] Needless to say, the religious teachers and commentators of his day did not agree with him.

Biblical Visions

The first events of the Restoration had obvious biblical connections.[6] Joseph Smith described his earliest dramatic encounter with the Divine as a theophany of God and Jesus when he was fourteen years old. The First Vision, as Latter-day Saints call the event, put to the test words he read in the Bible about obtaining enlightenment through prayer: “Ask and you shall receive[,] knock and it shall be opened[,] seek and you shall find.” And “If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, . . . and it shall be given him.”[7] He wrote regarding the latter passage, “Never did any passage of scripture come with more power to the heart of man than this did at this time to mine,” so “at length I came to the conclusion that I must either remain in darkness and confusion, or else I must do as James directs, that is, ask of God.” The biblical passages provided the conduit to a new biblical event—Joseph Smith’s encounter with the God and Jesus of the Bible.

But for Joseph Smith, the First Vision was also a lesson in epistemology. Ancient texts would be important for him throughout his career, but the source of his knowledge would be revelation. Even before he went into the grove of trees on his father’s farm to pray, he had already come to the conclusion that the Bible could not be his only source for religious knowledge, because, as he later wrote, “the teachers of religion of the different sects understood the same passages of scripture so differently as to destroy all confidence in settling the question by an appeal to the Bible.” But after the First Vision, he was able to say, “I have learned for myself.”[8] This distinction would always remain important for him; his prophetic career would not be an appeal to the Bible but an appeal for, and to, his own gift of revelation. That a large portion of his revelations dealt with topics that had biblical roots makes his independence from the biblical text all the more significant.

Joseph Smith described his next revelatory events as a series of visits from an angel named Moroni, who made known to him the existence of the Book of Mormon. Those encounters have many biblical connections, not the least of which is the book itself, which soon would be known as the “Gold Bible.” He reported that the angel told him, “God had a work for me to do.” That work would include the translation of the Book of Mormon, but there would be much more. The long encounters with the angel were teaching sessions in which the young Prophet was trained for his life’s work, receiving “instruction and intelligence . . . respecting what the Lord was going to do and how and in what manner his kingdom was to be conducted in the last days.” Joseph Smith said that the angel taught him by quoting passage after passage from the Bible and offering “many explanations” regarding them.[9] In his primary history, he placed his focus on five scriptures that Moroni quoted and discussed, but he stated that the angel also “quoted many other passages.”[10] His associate Oliver Cowdery published three newspaper articles in which he identified thirty passages that Moroni quoted or discussed.[11] From them and from Moroni’s commentary regarding them, young Joseph Smith would gain one of his fundamental beliefs about scripture: much of the message of the prophets since ancient times was aimed toward the work of restoration to which God had called him.

Many of the Bible passages quoted by Moroni, according to the accounts of Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith, have become staple Mormon texts. The topics of those passages, and the interpretation given them by Latter-day Saints, have become foundational to the Mormon message. The following summary places them in the context in which Latter-day Saints understand them.

Scattering and restoration. The theme of apostasy and restoration is a bedrock of Mormonism. God destroyed and scattered ancient Israel because of wickedness, and the world continues in sin: “This people draw near me with their mouth, and with their lips do honour me.” But they “have removed their heart far from me, and their fear toward me is taught by the precept of men.”[12] It was these conditions that set the stage for the calling of Joseph Smith: “God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise, . . . the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty.”[13] A later revelation identifies Joseph Smith as the “rod out of the stem of Jesse” of whom Isaiah prophesied, “a servant in the hands of Christ.”[14] He would be one of God’s messengers to prepare the way for Jesus’ return.[15]

New revelation. In bringing about the Restoration, God would cause the “wisdom” of the world to perish and the “understanding of their prudent men” to be hidden.[16] He would pour out his spirit on all flesh, empowering all to enjoy divine spiritual gifts.[17] One of the great revelations would be the Book of Mormon, “a marvellous work and a wonder” foretold by the prophet Isaiah.[18]

Restoring divine power. Latter-day Saints see their temple worship suggested in Isaiah’s prophecy that in the last days, “the mountain of the Lord’s house” would be established.[19] The last two verses of the Old Testament (Malachi 4:5–6) play a key role in Latter-day Saint theology, foretelling the coming of Elijah to seal the hearts of parents and posterity. They see the fulfillment of the prophecy in Elijah’s appearing to Joseph Smith in 1836, restoring the power to bind in heaven what is bound on earth and making possible the work of Latter-day Saint temples.[20]

Gathering scattered Israel. Moroni quoted passages about Israel’s return to promised lands. From its dispersed and scattered condition, Israel in the last days would respond to the voice of God’s servants, “the watchmen upon the mount Ephraim,” who would say, “Arise ye, and let us go up to Zion, unto the holy Mount of the Lord our God.”[21] God would send out “fishers” and “hunters” to find his covenant people in the places of their scattering throughout the world. They would be gathered “from the east, and from the west, from the north, and from the south.”[22] The “outcasts of Israel” and the “dispersed of Judah” would set aside their enmity and become one. Even those not of the house of Israel would join by covenant. Gentiles, Israel, and Judah would come together “from the four corners of the earth.”[23]

End-time destruction of the world. Joseph Smith wrote that Moroni quoted Malachi as follows: “For behold, the day cometh that shall burn as an oven, and all the proud, yea, and all that do wickedly shall burn as stubble,” leaving them “neither root nor branch.”[24] This process of God’s judgment would be the “great and dreadful day of the Lord.” It would purify “like a refiner’s fire, and like fullers’ soap.” God’s judgments would be accompanied by “wonders in the heavens and in the earth. . . . The sun shall be turned into darkness, and the moon into blood.”[25]

The Second Coming of Jesus and his millennial reign. Moroni quoted, “The Lord, whom ye seek, shall suddenly come to his temple,” and “the Lord shall reign for ever, even thy God, O Zion, unto all generations.”[26] Latter-day Saints follow Joseph Smith’s lead in identifying Jesus as the Coming One in Old Testament prophecies who will usher in a millennium of peace. “With righteousness shall he judge the poor, and reprove with equity for the meek of the earth. . . . And righteousness shall be the girdle of his loins, and faithfulness the girdle of his reins.”[27] In that day, people will “beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more.” “The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them.”[28]

One of the remarkable features of these scriptures is that all but two of those listed by Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith come from the Old Testament. Contemporary writers favored the New Testament, and early Mormons cited the New Testament almost twice as often as they cited the Old Testament.[29] But Moroni’s message had its focus on end-time events, and the eschatological prophecies of Isaiah and Jeremiah, from which more than half of the passages come, fit the theme perfectly.

Mormonism’s primary interpretation of these verses is found in the context in which they were received—the angel’s instructions to Joseph Smith regarding his mission and the course of the Restoration to the end of time. The passages, and the interpretations Joseph Smith and his followers placed on them, are vintage Mormonism.[30] The setting in which they became part of the message places them among the founding texts of Joseph Smith’s biblical restoration. Some other Christians in his day used some of these scriptures with similar interpretations.[31] But these are the exceptions, as most of the verses are interpreted in Mormon sources very differently from in non-Mormon sources.

Historian Philip Barlow has pointed out that Joseph Smith and his followers read most of the Bible literally.[32] In reading scripture literally they were not alone, but the distinctiveness of their literalism was that they believed that the prophecies of the Bible were fulfilled in Mormonism itself. Consider the belief in the literal building of a latter-day temple—a “mountain of the Lord’s house” in Isaiah’s prophecy—in contrast to its interpretation as a metaphor for the Christian Church (among other things) in standard commentaries.[33] Perhaps the literal interpretation is less intriguing than the idea that it would be Latter-day Saints who would be building the prophesied temple in the last days. Writers from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries often assigned to the days of Jesus and the Apostles the fulfillment of scriptures that Mormonism sets in the context of the latter-day Restoration. Notable examples are Joel 2:28–29 and Malachi 4:5–6, in which Latter-day Saints see the restoration of spiritual gifts and powers to Joseph Smith and the church he founded.[34] And Mormonism’s expansive view of the restoration of Israel goes well beyond what most commentators envisioned, again pointing to Mormonism as the fulfillment.[35] In all, the nontraditional meanings that Latter-day Saints give to these verses, their juxtaposition to the narrative of the Restoration, and the belief that they foretell the work initiated by Joseph Smith make both their individual interpretations and their collective message uniquely Mormon.

Joseph Smith recounted that the early days of the Restoration also included visits from well-known Bible characters who came to give him authority—John the Baptist and the Apostles Peter, James, and John. The Baptist, Joseph Smith announced, restored the priesthood of ancient Israel, which he inherited through the lineage of his ancestor Aaron. The three Apostles restored a higher priesthood, called the Melchizedek Priesthood, and the apostolic powers they received from Jesus Christ. Thus, in Joseph Smith’s restoration of biblical antiquity, the gifts and powers of both the Old and the New Testaments would be realized again in the last days.

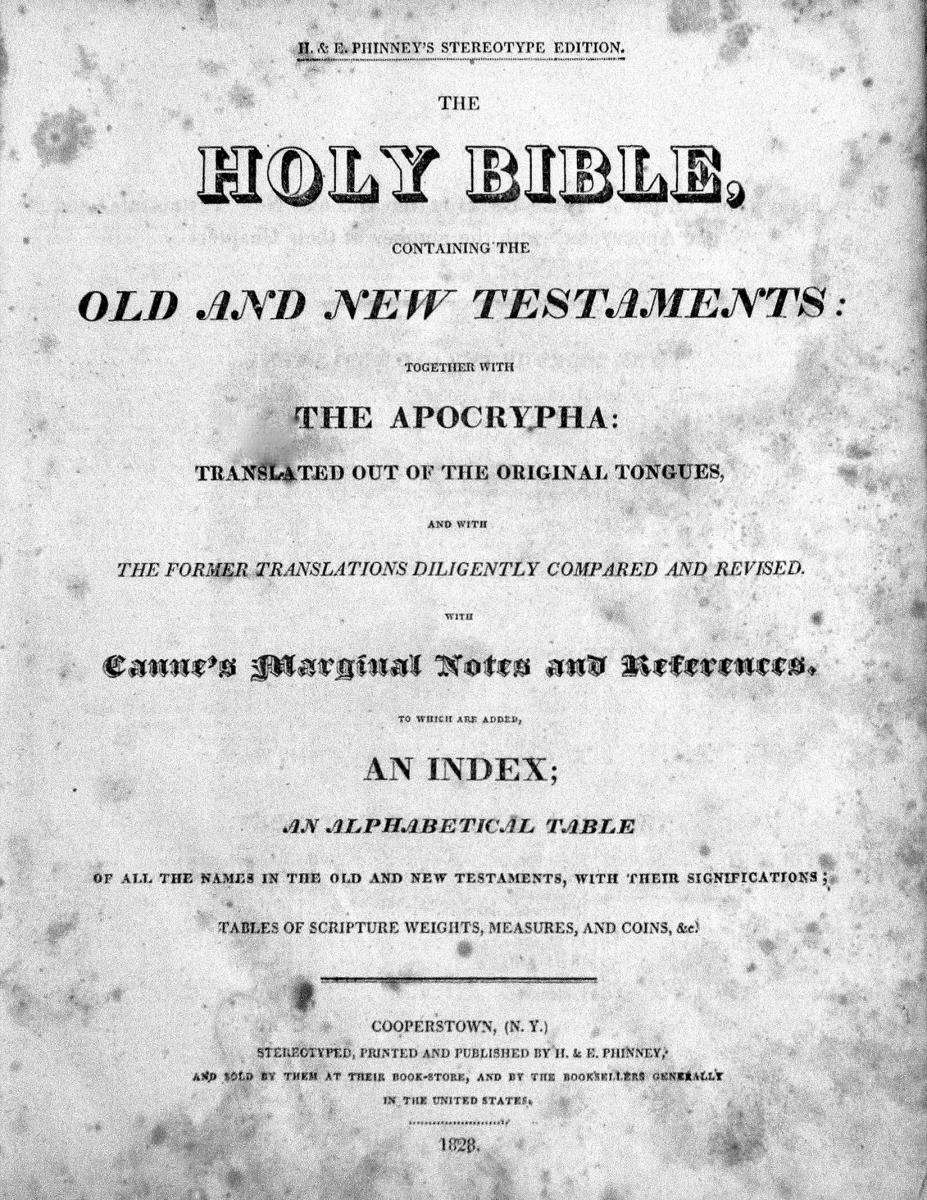

Title page, H. & E. Phinney King James Bible, 1828; same edition that Joseph's Smith used for New Translation of the Bible.

Title page, H. & E. Phinney King James Bible, 1828; same edition that Joseph's Smith used for New Translation of the Bible.

Biblical Revelation

Over the course of Joseph Smith’s life, he recorded well over a hundred texts that early Latter-day Saints received as revelations—the expression of God’s word to his Church. Most of them were published in his lifetime, some originally in Mormon newspapers. Since 1835 they have been collected in a volume called the Doctrine and Covenants. Several of Joseph Smith’s other narratives and translations are in a collection called the Pearl of Great Price (first published in 1851). Both of these volumes are still in print and are part of the Latter-day Saint canon.

We usually do not think of Joseph Smith’s revelations as biblical texts, but in many ways they are. Scholars have pointed out how the language of the revelations abounds in King James vocabulary and phraseology.[36] But beyond that, the revelations are closely tied to the Bible because so much of their content deals with themes from the Old and New Testaments. This is deliberate because the idea of the Restoration presupposes that Christianity would be on the earth before the days of Joseph Smith, and the Bible would be the means by which it would be preserved and spread. What was to be restored in the latter days would be the gospel’s fullness, not its already-present general principles and beliefs. Among the topics of the revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants are God and Jesus, the Holy Ghost, faith, repentance, baptism, justice, mercy, resurrection, spiritual gifts, the last days, the Second Coming of Jesus, and a thousand years of millennial peace. All of these are easily recognized as biblical concepts and were familiar to Joseph Smith’s followers from their prior association with other Christian denominations. None were introduced for the first time in the new revelations, yet the revelations add significant new interpretations to each of them. In some cases, Latter-day Saints understand the topics in much the same way that other Christians do. But in many instances, the revelations add ideas that go well beyond what is found in the Bible and thus depart radically from Christian tradition.

Some of the revelations deal explicitly with passages, people, and events from the Old and New Testaments. One, for example, contains a new account of the Olivet Discourse from Matthew 24 and another, an explanation of the parable of the wheat and the tares from Matthew 13.[37] A revelation fleshes out an account recorded in John 21, and others provide explanations for passages in 1 Corinthians.[38] Joseph Smith’s doctrine of different degrees of heaven in the afterlife springs from a passage in John 5.[39] Biblical priesthood is discussed, as are the lives of Adam, Enoch, Moses, and other luminaries from the Old Testament.[40] Even the organization of the Church comes from revelations relating to the Bible, with the Twelve, the Seventy,[41] and “the same organization that existed in the primitive church.”[42] And the Prophet said that his ideas for governing councils came to him in a vision of Peter administering the church in ancient times.[43]

One broad example—the idea of the temple—will illustrate the extent to which the Prophet’s revelations expand and, in some cases, radically redefine biblical concepts. In the Old and New Testaments, the temple is central to Israel’s formal worship system. It was the only approved setting for Israel’s most sacred rites, and it was the location to which all Israelite men were to gather three times each year.

Joseph Smith’s biblical Restoration would require the restoration of sacred buildings like these. “What was the object of Gathering the Jews together or the people of God in any age of the world [?], the main object was to build unto the Lord an house whereby he could reveal unto his people the ordinances of his house and glories of his kingdom & teach the peopl[e] the ways of salvation. . . . It is for the same purpose that God gathers togethe[r] the people in the last days to build unto the Lord an house to prepare them for the ordinances & endowment washings & anointings &c.”[44] Joseph Smith’s ideas regarding the temple were not clear all at once but came to him in stages. The first references to building a house of God came in a revelation of 1831 without mention of what its purpose would be.[45] When instructions were received later to build a temple in the Church’s central location of Kirtland, Ohio, the revelation called it “a house of prayer, a house of fasting, a house of faith, a house of learning, a house of glory, a house of order, a house of God.” A later revelation said it would be “for your sacrament offering, and for your preaching, and your fasting, and your praying, and the offering up of your most holy desires,” and “for the school of mine apostles.”[46] One week after the building’s dedication, Joseph Smith recorded in his journal that as he and Oliver Cowdery were praying in it, Jesus appeared to them, saying, “I have accepted this house and my name shall be here; and I will manifest myself to my people, in mercy, in this House.” Then Moses, Elias, and Elijah appeared to the two men and invested them with heavenly powers that they had possessed in biblical times.[47]

The function of Joseph Smith’s temple would not be at all like that of the temples of ancient Israel, with animal sacrifices and incense offerings. Its primary use would be as a meetinghouse for regular worship services, but with additional use as an administrative headquarters and a school. Yet above all else, the temple was understood to be a place of revelation.

The Prophet recorded in his journal early in 1836 that he learned in a temple vision that “all who have died without a knowledge of this gospel, who would have received it, if they had been permit[t]-ed to tarry, shall be heirs of the celestial kingdom of God.”[48] In 1838 he stated: “All those who have not had an opportunity of hearing the gospel, and being administered to by an inspired man in the flesh, must have it hereafter, before they can be finally judged.”[49] These statements represent the beginnings of what Latter-day Saints call the “redemption of the dead”—the doctrine that individuals in the world of departed spirits can embrace the gospel there and that people on earth can vicariously administer saving rites to them in the temple. For Joseph Smith, this was a biblical doctrine. He quoted from Paul to argue that it continued a practice from New Testament times: “Else what shall they do which are baptized for the dead, if the dead rise not at all? why are they then baptized for the dead?”[50]

In 1842 Joseph Smith introduced what he called the endowment, a temple ritual involving a sequence of covenants and blessings. He later put in writing a revelation on the eternity of temple marriages. In it we read that marriages performed under the authority of the restored priesthood will be valid not only on earth but in the eternal world as well.[51] After the temple in Nauvoo, Illinois, was completed, it would be the location where eternal marriages would be performed.

It would be impossible to argue that Joseph Smith’s idea of the temple—or the associated ideas of redeeming the dead and eternal marriages—grew naturally out of the biblical text. Yet he believed that these were necessary parts of the biblical Restoration. Nor did his temple ideas result naturally from his environment. Christians from the first century onward viewed the temple as something belonging to the old covenant of Moses. Most commentators saw no need for such a building in the Christian age.[52] It has been argued that some of the formal aspects of Joseph Smith’s temple rituals were borrowed from Masonry, which also used the word temple for the buildings in which its ceremonies took place.[53] And there may have been other Christian churches that used the word temple in the names of their buildings. Yet none of these examples can be shown to be true models for Joseph Smith’s temple concept, which expanded unrecognizably beyond any possible antecedents. As such, Joseph Smith’s vision of temples in the last days remains unique to him.

Biblical Translation

Perhaps as much of Joseph Smith’s exposure to the ancient world came through the biblical texts he produced, particularly through his revision of the Bible, as through any other source. He began his ambitious editing of the Bible in June 1830 and completed it about three years later. He went through the Bible from cover to cover, although not quite in that order, and dictated 446 pages of revisions to his scribes. In the process, he produced new interpretations of biblical passages, people, and events and inserted new text that Mormons believe may include material that had been lost during the Bible’s transmission.[54] The Prophet made changes, additions, and corrections in over three thousand verses. Many were small rewordings of King James language to make the text more clear and understandable for modern readers. But in some parts of the Bible, much new material was added, such as in the Genesis chapters that are included in the Pearl of Great Price. Joseph Smith and his contemporaries referred to the revision as the “New Translation.”[55]

From working on his Bible revision, Joseph Smith concluded much about the ancient world, but very little of what he concluded would be recognizable to other Christians. None of the details of his New Translation are as important as the one fundamental principle that came to underlie much of his biblical teaching throughout his life: the fulness of the gospel of Jesus Christ was revealed in the beginning of human history and always was the only means of human salvation. This is made known in dramatic ways in the New Translation, starting with an account of the revelation of Christianity to Adam and Eve: “And in that day, the Holy Ghost fell upon Adam, which beareth record of the Father & the Son Saying I am the only begotten of the father from the begining hence forth & forever; that as thou hast fallen, thou mayest be redeemed, & all mankind, even as many as will.” God said further to Adam, “If thou wilt turn unto me, & hearken unto my voice & believe, & repent of all thy transgressions, & be baptized, even in water, in the name of mine only begotten Son, who is full of grace & truth; who is Jesus Christ; the only name which shall be given under Heaven, whereby salvation shall come unto the children of men, [then] ye shall receive the gift of the holy Ghost.”[56]

The New Translation tells us that Adam and Eve’s descendants were Christians. Noah, for example, taught, “Believe & repent of your sins & be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ the son of God even as our fathers did & ye shall receive the Holy Ghost.”[57] Remarkable passages like these from Joseph Smith’s reading of the Bible provided a perspective on the ancient world that was far outside over two thousand years of biblical tradition.

An editorial in the Church’s newspaper The Evening and Morning Star expressed the Prophet’s view on the gospel’s antiquity: “Perhaps, our friends will say, that the gospel and its ordinances were not known till the days of John the son of Zecharias, in the days of Herod the king of Judea. But we will here look at this point: For our own part, we cannot believe, that the ancients in all ages were so ignorant of the system of heaven as many suppose, since all that were ever saved, were saved through the power of this great plan of redemption, as much so before the coming of Christ as since.” For Joseph Smith, this was one of the basic principles of the human experience. If it were otherwise, “God has had different plans in operation, (if we may so express it,) to bring men back to dwell with himself; and this we cannot believe, since there has been no change in the constitution of man since he fell.” “The gospel,” we are told, “was preached to Abraham. We would like to be informed in what name the gospel was then preached, whether it was in the name of Christ or some other name? If in any other name, was it the gospel?”

The Book of Mormon, published before the beginning of Joseph Smith’s work on the Bible, depicts ancient worshipers of Jesus offering sacrifices in anticipation of Jesus’ earthly coming. Joseph Smith did not view this as incongruous but in harmony with the real purpose of the sacrifices, which “served, as we said before, to open their eyes, and enabled them to look forward to the time of the coming of the Savior, and to rejoice in his redemption.” In doing so, they learned to “rely upon him alone as the author of their salvation.”[58]

These ideas go well beyond simply reading the Old Testament through Christian (or Mormon) lenses. Joseph Smith was rewriting history here, the primeval history of the human family, and putting Jesus at its center from the very beginning. The thought that the Christian gospel was revealed to Adam and Eve—making it the first religion in human history—was virtually unique in his generation.[59] Yet it is a thread that runs not only through the scriptures he brought forth but also through his interpretation of the Old and New Testaments. Animal sacrifice, as we read in the New Translation, was “a similitude of the Sacrifice of the only begotten of the Father, which is full of grace & truth.” The sacrifices undertaken by Abraham and other Saints in antiquity were not, like those of their contemporaries, to provide food for their hungry gods but to look to the future time in which the true God, Jesus Christ, would sacrifice himself for the blessing of all humankind. Thus Abraham “looked forth and saw the days of the Son of man, & was glad.”[60]

In Joseph Smith’s view of biblical antiquity, there was a fundamental difference between the worship of believers before the time of Moses and Israel’s religion thereafter. His belief in a Christian context for the stories in Genesis rewrites that book in a dramatic way, but his understanding of the law of Moses and its origin rewrites the rest of the Bible. The New Translation tells us that as a result of Israel’s rebellion that culminated in the golden calf incident, God took from Israel “the everlasting covenant of the holy Priesthood.”[61] The highest authority—the priesthood of Melchizedek—was withdrawn, and the law of Moses was instituted. God left “the lesser priesthood”—the priesthood of Aaron—“which the Lord in his wrath caused to continue with the house of Aaron among the children of Israel until John.”[62] As we have seen, Joseph Smith reported that as part of the “restitution of all things,” both of these priesthoods were restored to him for the benefit of God’s work in the latter days.

Joseph Smith as Bible Commentator

The first published Mormon Bible commentary was Oliver Cowdery’s discussion of Zephaniah.[63] Joseph Smith did not follow suit. He never wrote a commentary, nor did he show any inclination to codify his interpretations in any way outside of his revelations and translations. But throughout his career, he used Bible passages as illustrations and explanations in letters and editorials. In his sermons also, he commented on Bible passages frequently, and because many of those sermons were recorded by listeners, we have sources for much of his biblical thought. For the Nauvoo period, the time in which he spoke in large public settings the most, we have primary records for over 170 of his discourses. In most of his doctrinal sermons, he quoted, paraphrased, or reasoned out of the Bible, eventually touching on hundreds of verses.[64] These Bible-based sermons became one of the primary means by which he communicated with the Saints. Yet in them, as Barlow has pointed out, his objective was “rarely to interpret and defer to the Bible for its own sake.”[65] It was, instead, to unfold the ongoing development of his beliefs to the Church. Nor did he, in his sermons, “preach strictly from the Bible in Protestant fashion.”[66] Indeed, if what attracted early converts was the familiar voice of the Bible in the Mormon message, what they heard in Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo sermons was an expanded gospel that started from the familiar but projected beyond anything they had heard before.

In 1994 I published a book called Joseph Smith’s Commentary on the Bible. For it, I collected out of primary sources all of the known commentary on biblical passages that Joseph Smith gave in his sermons and writings. One thing that characterizes those excerpts is how freely the commentary flowed from his consciousness, even if it might not seem to others to flow freely from the text. I know of no instance in which he turned to a printed commentary to help him understand a biblical text. Some of his interpretations may not have been unique, and some may have agreed with the views of others. But those are exceptions. And further, none of that is to the point. Joseph Smith believed that he understood the Bible as it was meant to be understood, independent of any earthly source.

Two examples of commentary from his sermons will suffice to show the unique nature of the Prophet’s interpretations. In commenting on the account of Jesus driving evil spirits out of a man (or men) that subsequently possessed a herd of pigs, he stated: “The great principle of happiness consists in having a body. The Devil has no body, and herein is his punishment. He is pleased when he can obtain the tabernacle of [a] man and when cast out by the Savior he asked to go into the herd of swine showing that he would prefer a swine’s body to having none. All beings who have bodies have power over those who have not. The devil has no power over us only as we permit him; the moment we revolt at anything which comes from God[,] the Devil takes power.”[67] Standard commentaries focused on the obvious features of the story.[68] Joseph Smith’s, however, provides an underlying ontological framework toward understanding both Satan and humans.

The second example provides an explanation for a statement from Jesus in the Olivet Discourse: “And this gospel of the kingdom shall be preached in all the world for a witness unto all nations; and then shall the end come.”[69] Joseph Smith interpreted the passage to foretell the revelation of the gospel to a witness, who would take it to the world in the last days.

When it is rightly understood it will be edifying. .. . The Savior said, when those tribulations should take place, it should be committed to a man, who should be a witness over the whole world, the keys of knowledge, power, and revelations, should be revealed to a witness who should hold the testimony to the world; it has always been my province to dig up hidden mysteries, new things, for my hearers. . . . All the testimony is, that the Lord in the last days would commit the keys of the Priesthood to a witness over all people—has the Gospel of the Kingdom commenced in the last days? and will God take it from the man, until he takes him, himself? . . . John saw the angel having the holy Priesthood who should preach the everlasting gospel to all nations,[70]—God had an angel, a special messenger, ordained, & prepared for that purpose in the last days. . . . Every man who has a calling to minister to the Inhabitants of the world, was ordained to that very purpose in the Grand Council of Heaven before this world was—I suppose that I was ordained to this very office in that grand Council. . . . God will always protect me until my mission is fulfilled.[71]

Not all commentaries current in Joseph Smith’s day shared his belief that this prophecy was to be fulfilled in an end-time setting.[72] And his understanding that he was its fulfillment was certainly unique to him.

But if Joseph Smith’s primary biblical hermeneutic was the antiquity of, and the universal need for, Christ’s gospel, his secondary interpretive principle, as we have already seen, was that his own prophetic mission continued that of the prophets of the past and that the work in which he was engaged was the very culmination of the efforts of all the prophets before him. He believed that his was “the dispensation of the fulness of times, when . . . all things shall be restored, as spoken of by all the holy prophets since the world began: for in it will take place the glorious fulfillment of the promises made to the fathers.”[73] Indeed, “the dispensation of the fulness of times will bring to light the things that have been revealed in all former dispensations, also other things that have not been before revealed.”[74]

Joseph Smith’s Biblical Modernity

Latter-day Saints read the Bible with a view of antiquity informed by Joseph Smith’s revelations and his reading of the Bible. Together, those sources create a vision of the ancient world and its history that contrasts dramatically with traditional Christian views. To Joseph Smith, however, his nontraditional interpretation came naturally from the text and was not something he imposed on it. “We teach nothing but what the Bible teaches,” he said.[75] Yet again, for him the source of his interpretation was not the text itself but the revelation he received to guide him to understand it. He said, “God may correct the scripture by me if he choose,”[76] and, “I have the oldest Book in the world & the Holy Ghost[.] I thank God for the old Book but more for the Holy Ghost.”[77]

Joseph Smith’s revelations and translations mention or discuss—by name—virtually every important person in the Bible, forging a link from him and his followers back to their counterparts in the ancient world. In turn, he believed that the people in the Bible anticipated his time and the work he would do. “They have looked forward with joyful anticipation to the day in which we lived; and fired with heavenly and joyful anticipations they have sung, and [written], and prophesied of this our day; . . . we are the favored people that God has made choice of to bring about the Latter Day glory; it is left for us to see, participate in, and help to roll forward the Latter Day glory; ‘the dispensation of the fulness of times, when God will gather together all things that are in heaven, and all things that are upon the earth, even in one.’”[78]

Latter-day Saints (myself included) are fond of quoting Alexander Campbell’s complaint about the Book of Mormon—it conveniently dealt with, and provided answers for, “every error and almost every truth discussed in New York for the last ten years.”[79] The same could have been said about Joseph Smith’s revelations and his New Translation. Some modern observers, as well, have suggested conscious intent on his part to address problems in Christian theology and biblical interpretation.[80] But the evidence does not show intent of that sort. Some of the revelations he announced did come in answer to questions he had. But those questions were almost always provoked by previous revelations and by the situations he and his followers faced attempting to comply with what they perceived as God’s will. The revelations themselves rarely have themes but usually skip from subject to subject, suggesting that Joseph Smith’s ideas came to him spontaneously and unsystematically. The history of his well-documented life does not show him seeking to deal with the beliefs of other faiths. In all, he seemed to be as surprised as his followers by the content of new communications from God.

This leads to the following question: Did Joseph Smith (who was an uneducated farmer) realize (at age twenty-three when he produced the text of the Book of Mormon and at twenty-four when he produced the new Genesis chapters) that his new scriptures were proposing solutions to problems that thoughtful Christians had struggled with for two millennia? If he, through the construct of his biblical antiquity, was responding to the beliefs of other Christians, he seemed oddly unaware that he was doing so. Richard Bushman asks the follow-up question: “Did Joseph realize he was departing from traditional Christian theology? The record of his revelations and sermons gives no sense of him arguing against received beliefs. He does not refer to other thinkers as foils for his views. . . . His storytelling was oracular rather than argumentative. He made pronouncements on the authority of his own inspiration, heedless of current opinion.”[81] The sources support this analysis, suggesting that Joseph Smith was perhaps not even unaware of many of the theological issues with which other Christians were grappling—theological issues for which Latter-day Saints find answers in his teachings and translations. Thus whatever one might conclude about the ultimate source of his theological intuition and his unique views regarding the Bible and its world, it would be difficult to argue that they are simply the product of the common Christian beliefs of his day.

Notes

[1]“Letter from Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons, October 1, 1842, 935 (D&C 128:18).

[2] Acts 3:21. Unless otherwise indicated, all Bible quotations are from the King James translation, the common Bible of early Latter-day Saints.

[3] Kent P. Jackson, “Joseph Smith and the Bible,” Scottish Journal of Theology 63, no. 1 (2010): 24–40.

[4] Adam Clarke, John Gill, and Thomas Scott are mentioned specifically. See Evening and Morning Star, August 1832, 21; Messenger and Advocate, April 1835, 97; Times and Seasons, September 1, 1842, 907. Disdain for commentators is evidenced in Times and Seasons, November 15, 1840, 215; January 1, 1842, 645; August 1, 1843, 285.

[5] Mathew S. Davis to Mary Davis, February 6, 1840, in Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1978), 4:78.

[6] On the topic of the Bible and Joseph Smith, see Gordon Irving, “The Mormons and the Bible in the 1830s,” BYU Studies 13, no. 4 (1973): 473–88; Grant Underwood, “Joseph Smith’s Use of the Old Testament,” in The Old Testament and the Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Randall Book, 1986), 381–413; Philip L. Barlow, Mormons and the Bible: The Place of the Latter-day Saints in American Religion, updated ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), chapters 1 and 2; Kent P. Jackson, comp. and ed., Joseph Smith’s Commentary on the Bible (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994); Kent P. Jackson, ed., The King James Bible and the Restoration (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2011); Jackson, “The King James Bible in the Days of Joseph Smith,” in The King James Bible and the Restoration, 138–61; Jackson, “The King James Bible and the Joseph Smith Translation,” in The King James Bible and the Restoration, 197–214; Jackson, “Joseph Smith and the Bible,” 24–40.

[7] Matthew 7:7 (paraphrased in Joseph Smith’s 1835 account of the First Vision), Joseph Smith, 1835–1836 Journal, 23 (November 9–11, 1835), in Dean C. Jessee, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, eds., Journals, Volume 1: 1832–1839, vol. 1 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2008), 87; hereafter JSP, J1. James 1:5; Joseph Smith, “History of Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons, March 15, 1842, 727–28 (Joseph Smith–History 1:11).

[8]“History of Joseph Smith,” March 15, 1842, 728 (Joseph Smith–History 1:12–13, 20).

[9]“History of Joseph Smith,” April 15, 1842, 753 (Joseph Smith–History 1:33, 41); May 2, 1842, 771 (Joseph Smith–History 1:54).

[10]“History of Joseph Smith,” April 15, 1842, 753 (Joseph Smith–History 1:41).

[11] Cowdery’s articles are in the form of letters addressed to W. W. Phelps; “Letter IV. To W. W. Phelps, Esq.,” Messenger and Advocate, February 1835, 77–80; “Letter VI. To W. W. Phelps, Esq.,” Messenger and Advocate, April 1835, 108–12; “Letter VII. To W. W. Phelps, Esq.,” Messenger and Advocate, July 1835, 156–59. The combined Bible passages are as follows (those cited by Joseph Smith are in italics): Deuteronomy 32:23–24, 43; Psalms 100:1–2; 107:1–7; 144:11–12, 13; 146:10; Isaiah 1:7, 23–24, 25–26; 2:1–4; 4:5–6; 11:1–16; 29:11, 13, 14; 43:6; Jeremiah 16:16; 30:18–21; 31:1, 6, 8–9, 27–28, 31–33; 50:4–5; Joel 2:28–32; Malachi 3:1–4 (?); 4:1–6; Acts 3:22–23; 1 Corinthians 1:27–29.

[12] Isaiah 29:13.

[13] 1 Corinthians 1:27.

[14] Isaiah 11:1; revelation, March, 1838 (D&C 113:4).

[15] Malachi 3:1.

[16] Isaiah 29:14.

[17] Joel 2:28–29.

[18] Isaiah 29:11, 14.

[19] Isaiah 2:1–4.

[20] See vision, April 3, 1836 (D&C 110:13–16). We have more extant commentary from Joseph Smith on Malachi 4:5–6 than on any other passage; see Jackson, Joseph Smith’s Commentary on the Bible, 69–74.

[21] Jeremiah 31:6, as worded in Oliver Cowdery’s account. The King James translation does not include “the holy Mount of.” See Cowdery, “Letter VI,” 111.

[22] Jeremiah 16:16; Psalm 107:3; cf. Isaiah 43:6; Jeremiah 31:8.

[23] Isaiah 11:12–13; cf. Jeremiah 50:4.

[24]“History of Joseph Smith,” April 15, 1842, 753 (Joseph Smith–History 1:37); cf. Malachi 4:1.

[25] Joel 2:30–31.

[26] Malachi 3:1; Psalm 146:10.

[27] Isaiah 11:2, 4–5. Mormonism is decidedly premillennialist. See Grant Underwood, The Millenarian World of Early Mormonism (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993).

[28] Isaiah 2:4; 11:6.

[29] Irving, “The Mormons and the Bible in the 1830s,” 478–80.

[30] Irving finds many of the same themes emphasized in the writings of early Latter-day Saints; see “The Mormons and the Bible in the 1830s,” 480–83, 486–87.

[31] See Thomas Scott on Isaiah 2:2–5. He places the fulfillment “in the times of the Messiah,” “which intervene between his coming and the end of the world.” Scott (1747–1821) was an Anglican priest who became an Evangelical. His commentary was printed in a variety of forms by different publishers. See, for example, The Holy Bible. Stereotyped Edition from the Fifth London Edition (Boston: Samuel T. Armstrong, Crocker and Brewster; New York: J. Leavitt, 1827).

[32] Barlow sees a “selective literalism” among Joseph Smith and the Latter-day Saints; see Mormons and the Bible, 33–40, 70–71.

[33] Isaiah 2:4; see Matthew Henry’s commentary: “Christianity shall then be the mountain of the Lord’s house; where that is professed God will grant his presence, receive his people’s homage, and grant instruction and blessing, as he did of old in the temple of Mount Zion.” Henry (1662–1714) was a Presbyterian whose commentary was published in a variety of ways and sometimes in conjunction with Scott’s. An American publication is An Exposition of the Old and New Testaments . . . with Practical Remarks and Observations by Matthew Henry (New York: John P. Haven; Pittsburgh: Robert Patterson; Philadelphia: Towar and Hogan, 1828). See also Matthew Poole on Isaiah 2:4: “The temple of the Lord which is upon Mount Moriah; which yet is not to be understood literally of that material temple, but mystically of the church of God, as appears from the next following words, which will not admit of a literal interpretation.” Poole (1624–79) was a Presbyterian Nonconformist whose commentary, finished by colleagues after his death, went through several publishers. See, for example, Annotations upon the Holy Bible, vol. 1 (London: Thomas Parkhurst, Jonathan Robinson, Thomas Cockerill Sr., Bradbazon Ailmer, John Lawrence, and John Taylor, 1696); vol. 2 (London: Thomas Parkhurst, Dorman Newman, Jonathan Robinson, Brabazon Ailmer, and Thomas Cockerill, 1688).

[34] John Gill, for example, identifies Elijah in Malachi 4:5–6: “Not the Tishbite, as the Septuagint version wrongly inserts instead of prophet; not Elijah in person, who lived in the times of Ahab; but John the Baptist, who was to come in the power and spirit of Elijah.” Gill (1697–1771) was a Baptist and a Calvinist. See An Exposition of the Old Testament (Philadelphia: William W. Woodward, 1817–19).

[35] In contrast to what Latter-day Saints understand as Ephraim initiating the gathering of Israel in the latter days (Jeremiah 31:6), see Poole: “The best interpreters judge that this prophecy was fulfilled under the gospel; for both Galilee and Samaria received the gospel, as appeareth from Acts viii. 1, 5, 9, 14; ix. 31.” See also Scott, quoting Lowth: “The word may be applied to those evangelical preachers, who should be instruments in converting the Jews to Christ, and bringing them into the church.”

[36] Barlow, Mormons and the Bible, 21–26, 68; Ellis T. Rasmussen, “Textual Parallels to the Doctrine and Covenants and Book of Commandments as Found in the Bible” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1951); Eric D. Huntsman, “The King James Bible and the Doctrine and Covenants,” in Jackson, The King James Bible and the Restoration, 182–96.

[37] Revelation, March 7, 1831 (D&C 45); and revelation, December 6, 1832 (D&C 86).

[38] Revelation, April 1829 (D&C 7); revelation, March 8, 1831 (D&C 46); and revelation, 1830 (D&C 74).

[39] Revelation, February 16, 1832 (D&C 76).

[40] Revelation, September 22–23, 1832 (D&C 84); and revelation, April 1835 (D&C 107).

[41] Revelation, March 28, 1835 (D&C 107:22–27).

[42] Joseph Smith, “Church History,” March 1, 1842, 709.

[43] Minutes, February 17, 1834, 29–30, in Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, Brent M. Rogers, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds. Documents, Volume 3: February 1833–March 1834, vol. 3 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historians, Press, 2014), 437–38.

[44] Discourse of June 11, 1843, recorded by Wilford Woodruff; in Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., The Words of Joseph Smith: The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1980), 212–13.

[45] See revelation, July 20, 1831 (D&C 57:3); and revelation, August 1, 1831 (D&C 58:57).

[46] Revelation, December 27–28, January 3, 1833 (D&C 88:119); and revelation, June 1, 1833 (D&C 95:16–17).

[47] Joseph Smith, 1835–36 Journal, 192 (April 3, 1836); JSP, J1:219 (D&C 110:3, 6–7, 9–10).

[48] Joseph Smith, 1835–36 Journal, 136–37 (January 21, 1836); JSP, J1:168 (D&C 137:7).

[49] Elders’ Journal, July 1838, 43.

[50] 1 Corinthians 15:29. Clarke calls this “the most difficult verse in the New Testament.” None of the major commentaries current in Joseph Smith’s day interpreted this verse the way he did, but both Gill and Scott acknowledge that some others had done so.

[51] Revelation, July 12, 1843 (D&C 132:15–19). Even the institution of polygamy, made known in the same revelation, was viewed as the restoration of a biblical practice.

[52] See Adam Clarke at Matthew 24:2. Clarke (1760–1832) was a Methodist whose massive commentary was a standard in Joseph Smith’s time. See Adam Clarke, The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments: The Text Printed from the Most Correct Copies of the Present Authorized Translation, Including the Marginal Readings and Parallel Texts, with a Commentary and Critical Notes (Baltimore: John J. Harrod, 1836).

[53] See the summary in Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 449–52.

[54] For the New Translation, see Scott H. Faulring, Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds., Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible—Original Manuscripts (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2004); Kent P. Jackson, The Book of Moses and the Joseph Smith Translation Manuscripts (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2005); Scott H. Faulring and Kent P. Jackson, eds., Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible: Electronic Library (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2011); Kent P. Jackson, “Joseph Smith’s Cooperstown Bible: The Historical Context of the Bible Used in the Joseph Smith Translation,” BYU Studies 40, no. 1 (2001): 41–70; Kent P. Jackson and Peter M. Jasinski, “The Process of Inspired Translation: Two Passages Translated Twice in the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible,” BYU Studies 42, no. 2 (2003): 35–64; Kent P. Jackson and Charles Swift, “The Ages of the Patriarchs in the Joseph Smith Translation,” in A Witness for the Restoration: Essays in Honor of Robert J. Matthews, ed. Kent P. Jackson and Andrew C. Skinner (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2007), 1–11; Kent P. Jackson, “New Discoveries in the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible,” rev. ed., in By Study and by Faith: Selections from the Religious Educator, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2009), 169–81; Kent P. Jackson, “Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet and Seer, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2010), 51–75.

[55] As also does a passage in the Doctrine and Covenants; see revelation, January 19, 1841 (D&C 124:89); Times and Seasons, July 1840, 140. See also Smith, History of the Church, 1:341, 365; 4:164. Since the late 1970s, the revision has been called commonly the “Joseph Smith Translation” (JST). The title Inspired Version refers to the edited, printed edition, published in Independence, Missouri, by the Community of Christ.

[56] Old Testament Manuscript 2, page 10, lines 21–25 (Moses 5:9); page 17, lines 31–37 (Moses 6:52); Faulring, Jackson, and Matthews, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 603, 612.

[57] Old Testament Manuscript 2, page 27, lines 8–10 (Moses 8:24); Faulring, Jackson, and Matthews, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 625.

[58]“The Elders of the Church in Kirtland, to their Brethren Abroad,” Evening and Morning Star, March 1834, 287. This was presumably authored by Joseph Smith. At the least, it was certainly written under his direction and expresses his views.

[59] Heikki Räisänen and Terryl L. Givens discuss others who desired or imagined Christianity before Christ and the theological issues that drove that desire; see Räisänen, “Joseph Smith as a Creative Interpreter of the Bible,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 43, no. 2 (summer 2010): 74–77; and Givens, “Joseph Smith: Prophecy, Process, and Plenitude,” in Joseph Smith Jr.: Reappraisals after Two Centuries, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Terryl L. Givens (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 114–15.

[60] Old Testament Manuscript 2, page 10, lines 21–25 (Moses 5:7); page 40, lines 34–35; Faulring, Jackson, and Matthews, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 603, 643.

[61] Old Testament Manuscript 2, page 72, lines 34–35 (Deuteronomy 10:2); Faulring, Jackson, and Matthews, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible, 709.

[62] Revelation, September 22–23, 1832 (D&C 84:24–27).

[63] Oliver Cowdery, “The Prophecy of Zephaniah,” Evening and Morning Star, February 1834, 132–33; March 1834, 140–42; April 1834, 148–49.

[64] See Kent P. Jackson, “The Prophet’s Teachings in Nauvoo,” in Joseph: Exploring the Life and Ministry of the Prophet, ed. Susan Easton Black and Andrew C. Skinner (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 367–79. The sermons are compiled in Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith. The impressive scripture index in this collection (pages 421–25) illustrates the breadth of Joseph Smith’s biblical teaching.

[65] Barlow, Mormons and the Bible, xxxii.

[66] Barlow, Mormons and the Bible, xxxiii.

[67] See Matthew 8:28–34; Mark 5:1–13; Luke 8:26–39; discourse of January 5, 1841, recorded by William Clayton; Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 60.

[68] See, for example, Matthew Henry on Matthew 8:28–34; and John Gill on Mark 5:1–13.

[69] Matthew 24:14.

[70] See Revelation 14:6.

[71] Discourse of May 12, 1844, recorded by Thomas Bullock; Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 366–67.

[72] Clarke, Gill, and Scott place the fulfillment in the first century, Henry sees a fulfillment in the first century and again at the end of time, and Poole does not take a position.

[73] Joseph Smith, “To the Saints Scattered Abroad,” Times and Seasons, October 1840, 178.

[74]“Minutes of a Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, held in Nauvoo, Ill, Commencing Oct. 1st, 1841,” Times and Seasons, October 15, 1841, 578.

[75] Mathew S. Davis to Mary Davis, February 6, 1840, in Smith, History of the Church, 4:78.

[76] Discourse of April 13, 1843, recorded by Willard Richards; Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 191.

[77] Discourse of April 7, 1844, recorded by Wilford Woodruff; Ehat and Cook, Words of Joseph Smith, 345.

[78]“The Temple,” Times and Seasons, May 2, 1842, 776.

[79]“He [Joseph Smith] decides all the great controversies;—infant baptism, ordination, the trinity, regeneration, repentance, justification, the fall of man, the atonement, transubstantiation, fasting, penance, church government, religious experience, the call to the ministry, the general resurrection, eternal punishment, who may baptize, and even the question of free masonry, republican government, and the rights of man.” Alexander Campbell, “Delusions,” Millennial Harbinger, February 7, 1831, 93.

[80] See, for example, Kathleen Flake, “Translating Time: The Nature and Function of Joseph Smith’s Narrative Canon,” Journal of Religion 87, no. 4 (October 2007): 511–27; Heikki Räisänen, “Joseph Smith as a Creative Interpreter of the Bible,” 64–85.

[81] Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 2005), 457-58.