Joseph Smith in the National Portrait Gallery

Anthony Sweat

Anthony R. Sweat was an associate teaching professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

Figure 1. Joseph Smith portrait by Adrian Lamb in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery permanent exhibit. Used with permission.

Figure 1. Joseph Smith portrait by Adrian Lamb in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery permanent exhibit. Used with permission.

In 1962 the United States Congress founded the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in Washington, DC, with the commission to collect portraits of “men and women who have made significant contributions to the history, development, and culture of the people of the United States.”[1] Its archives currently hold more than twenty-three hundred paintings, drawings, prints, photographs, sculptures, and other items. Of those twenty-three hundred, only about fourteen hundred portraits (roughly 6 percent of the collection) are on permanent display for the museum’s visitors—over one million annually.[2] A prominent portrait of Joseph Smith in a warm cherry frame is displayed on the first floor in the permanent East Gallery of the “American Origins” exhibit near a bust of Booker T. Washington (figure 2).

The purpose of this paper is to explore how this particular portrait of Joseph Smith became part of the National Portrait Gallery’s permanent display. This story follows a chronological flow that briefly outlines the development of portraiture in Western art and America, Joseph Smith’s portraits he sat for during his life, the establishment of the NPG in 1968, the events surrounding the inclusion of a Joseph Smith portrait in the NPG’s opening, and the Joseph Smith portrait that currently hangs in the NPG permanent display along with its origins. This paper will conclude with an analysis of the likeness of the NPG Joseph Smith portrait and what its presence may say about Joseph Smith and the Restoration’s place in the American nation.

Figure 2. Joseph Smith portrait (left wall) in the National Portrait Gallery’s “American Origins” exhibit. Photo by author.

Figure 2. Joseph Smith portrait (left wall) in the National Portrait Gallery’s “American Origins” exhibit. Photo by author.

The Prominence of Portraiture

Portrait painting is one of the most popular genres of Western art. Before photography, portraiture was used for thousands of years as the primary means to capture, idealize, and propagate the likeness of important or beloved individuals. A portrait “contains a divine force which not only makes absent men present . . . but moreover makes the dead seem almost alive,” Leon Alberti said in his classic 1435 work, On Painting.[3] Even Jesus makes a reference to portraiture when he referred to Caesar’s likeness on a Roman coin and instructionally asked, “Whose is this image and superscription?” (Matthew 22:20).

According to art historian Joanna Woodall, although portraiture has been popular for millennia, “the ‘rebirth’ of portraiture is considered a definitive feature of the Renaissance” (AD 1300–1600) and is characterized by paintings with “closely observed facial likeness, including idiosyncrasies and imperfections, to represent elite figures. . . . By the turn of the sixteenth century, the ‘realistic’ portrait was widespread.”[4] For popes, royalty, military leaders, politicians, scholars, and the beautiful, wealthy, and influential, a painted portrait was often a social status symbol. President John Adams quipped, “No penance is like having one’s picture done,”[5] yet—aware of portraits’ public import—he sat for no less than six portraits in his lifetime.[6] President Andrew Jackson knew and leveraged the power of personal portraiture to the extreme: he hired a full-time painter, Ralph Earl, to live with him at the White House, who “churned out Jackson portraits as quickly as possible.”[7]

Portraiture is the first artistic “genre to appear among the Saints,” writes Terryl Givens,[8] and it played a prominent role in early Latter-day Saint history. As an example, to help solidify his new position as the leader of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints after Joseph Smith’s death, Brigham Young commissioned and posed for a seven-foot-tall, full-body portrait by Selah Van Sickle in July of 1845. Brigham stands in the painting, staring directly at the viewer, with a filled bookshelf behind him. The Book of Mormon and Bible sit on a table in the foreground, and Brigham’s hand holds up a third book—Joseph’s book containing the names of the faithful called the “Book of the Law of the Lord.” This painting was hung on the east wall in the celestial room of the Nauvoo Temple so that when members directly entered the room, this “life-sized portrait sent a powerful message that Joseph Smith’s personal record book had passed to the hands of Brigham Young and only Brigham Young had the authority to deliver the law of the Lord to the Church.”[9]

Joseph Smith’s Portraits from Life

Like John Adams, Andrew Jackson, and many others, the Prophet Joseph Smith sat for a few artistic portraits during his lifetime. Joseph’s journal for 25 June 1842 says, “Set for the drawing of his profile. for Lithographing on city chart.”[10] This profile image, done by Sutcliffe Maudsley, was intended for inclusion in the bottom corner of the map of Nauvoo. The original painting was sent to the lithographer to re-create for the map (and thus the image on the map is a copy by another artist copying Maudsley’s drawing). The original Maudsley life drawing was lost until 1982, when it was rediscovered with some old books at a garage sale in Salt Lake City.[11] Joseph posed again (perhaps for Maudsley, although the artist is uncertain) for a profile drawing of the Prophet in a white suit. Desdemona Fullmer Smith, who donated the drawing to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1881, wrote, “This portrait of the Prophet Joseph Smith I saw taken while he stood up in Nauvoo with the white suit on that I made for him.”[12] Just a few months after his initial sitting for Maudsley, on 16 September 1842, the Prophet posed for another portrait: “Friday 16th. With brother [David] Rogers at home. bro R painting.” In comparison to his profile drawing by Maudsley (who may have used a pantograph technique to physically trace Joseph’s profile[13] ), this Brother Rogers sitting was for a multiday portrait, likely an oil painting given the amount of time it required. Joseph’s journal continues: “Saturday 17th. At home with brother [David] Rogers, painting. . . . Monday 19th. & Tuesday 20th. With brothers [David] Rogers. painting at his house.”[14]

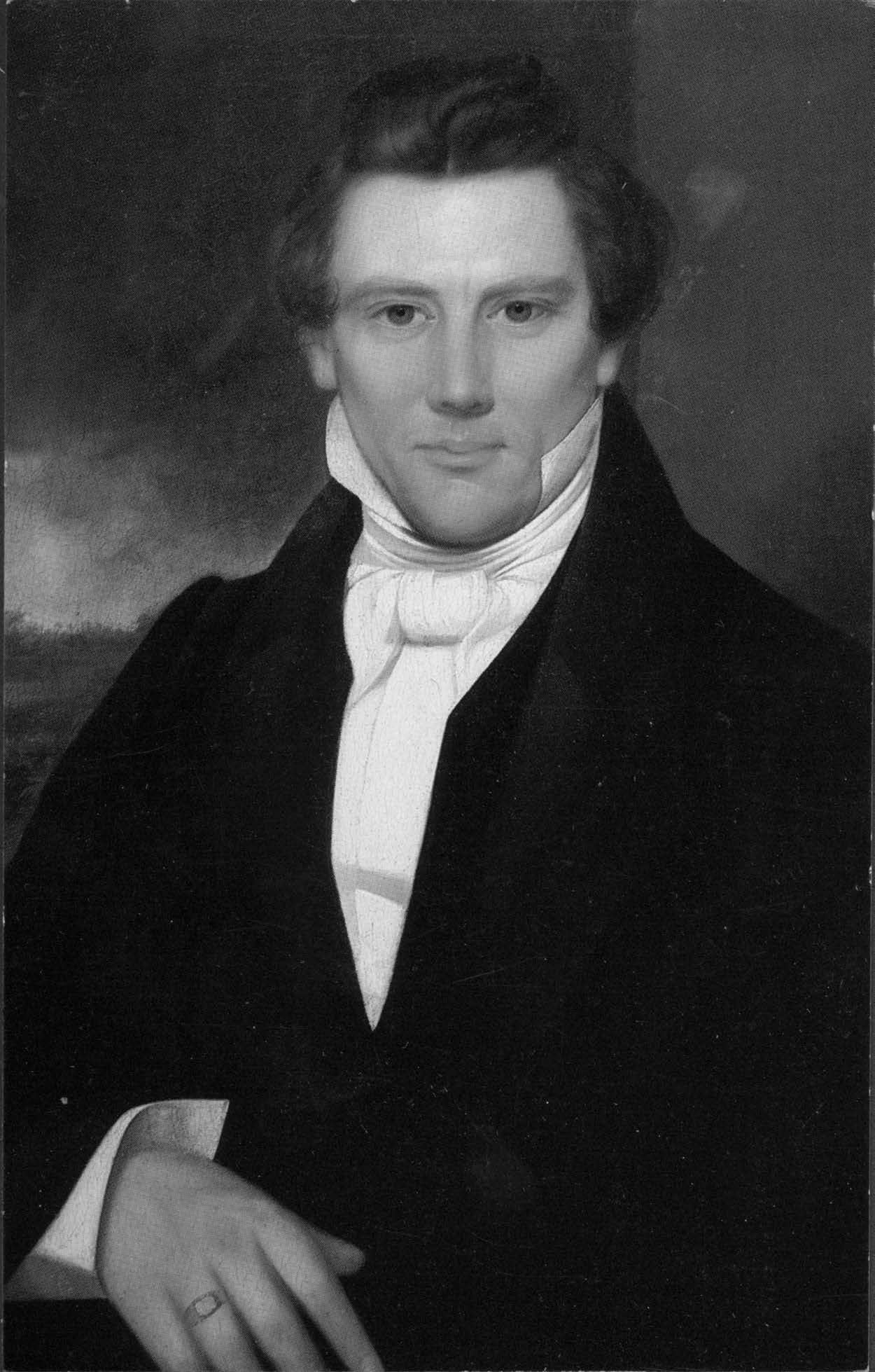

Glen Leonard, former director of the Church History Museum, concludes that the painting attributed to David Rogers from September 1842 is the well-known front-view oil painting of Joseph Smith (with a companion painting of Emma Smith) owned by the Community of Christ (formerly the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints), which hangs in their Temple Museum in Independence, Missouri (see figure 2). [15] The Community of Christ also attributes this painting to Rogers. [16] Notably, the Rogers portraits of Joseph and Emma have strong provenance. During Joseph’s life, the portraits hung in the sitting room in the lower southwest corner of the Mansion house and were later moved upstairs. Emma Smith then moved the portraits into the Nauvoo House when she moved there in the 1870s. When Latter-day Saint missionary Junius F. Wells visited Emma Smith in the winter of 1875–76, he recollected that Emma “entertained me very hospitably and showed me the painting [of Joseph], then hanging in her bedroom at the Nauvoo House.”[17] Elder Wells wrote that this “first and only full face portrait is an oil painting made by an artist named Rogers.”[18] However, there are some who debate whether this front-view image (or a profile oil painting of Joseph and a companion of Hyrum) is the “Brother Rogers” painting in question.[19] For ease of reference, however, I will refer to this well-known image attributed to David Rogers as the Rogers portrait throughout the remainder of this paper (figure 3).

Figure 3. Portrait of Joseph Smith, attributed to David Rogers, 1842. Courtesy of the Community of Christ.

Figure 3. Portrait of Joseph Smith, attributed to David Rogers, 1842. Courtesy of the Community of Christ.

The Rogers portrait of Joseph Smith has been reproduced numerous times. Two copies were made in 1899 for the Community of Christ. In the 1950s Israel Smith had it copied again by artist Harold Bullard. Another reproduction copy currently hangs in the bottom floor of the Salt Lake Temple. The original Rogers portraits of Joseph and Emma now hang in the Community of Christ Temple Museum in Independence, Missouri.[20] If the original Rogers painting of Joseph Smith hangs in Independence, Missouri, then which copied version of it hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC?

Establishing the National Portrait Gallery

As the new American nation grew in the eighteenth to twentieth centuries, prominent American portraits began to be collected by museums and institutions to preserve historic individuals and works of art. Portraits tell a story and serve to both preserve and create history. When the National Portrait Gallery in London opened in 1859, there was a general sentiment among some Americans to establish a similar gallery in the United States. As of the1920s, however, there was yet no established U.S. portrait gallery. In 1921 the Smithsonian—in conjunction with the National Gallery of Art—commissioned twenty portraits of World War I notables, which formed the nucleus of the nation’s first gallery of portraits.[21] In 1957 the old Patent Office in Washington, DC, was proposed to be demolished, but due to public opposition Congress decided to turn the building over to the Smithsonian and make it into a museum. In 1962 the U.S. Congress authorized the founding of the National Portrait Gallery, approved by President John F. Kennedy. Title 20 of the U.S. Code, section 75b for the “Establishment of National Portrait Gallery,” reads as follows: “There is established in the Smithsonian Institution a bureau which shall be known as the National Portrait Gallery . . . for the exhibition and study of portraiture and statuary depicting men and women who have made significant contributions to the history, development, and culture of the people of the United States and of the artists who created such portraiture and statuary.”[22]

Over the next six years, the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) labored to acquire its initial body of portraits and opened first to the public in 1968 with around six hundred portraits.[23] Many of the initial portraits were on loan. Brandon Fortune, chief curator of the NPG in 2019, said, “When the National Portrait Gallery was founded in 1962, it had no collection. During the next decade, as the museum staff gathered works by gift and purchase and transfer for the collection, they also researched available portraits of Americans who had great impact on our history and culture. Occasionally, the staff commissioned a copy of a painting in order to fill a gap when it was unlikely that the museum would ever be able to acquire an original portrait from life.”[24] Washington Post journalist Bob Thompson says, “Sometimes they [the NPG] tracked down portraits, and sometimes portraits came to them. Sometimes they scraped together money for purchases, and sometimes they pleaded for donations,” claiming that the opening show for the NPG could have been titled “Won’t Someone Give Us Some Pictures Like These—Please?”[25]

As portraits were originally acquired by the National Portrait Gallery, no portrait was obtained unless it or the artist was considered historically significant by the NPG staff and the NPG Commission, which commission—composed of curators and historians appointed by the Smithsonian regents—voted in each new addition.[26] The addition of new portraits continues today. Each month the commission meets to vote in or reject potential images. Other than portraits of U.S. presidents and their spouses, no portrait can be added to the permanent collection unless the subject has been deceased for ten years. The process of who gets admitted into the NPG can be contested. Bob Thompson continues, “The culling of notable Americans for admission to the National Portrait Gallery can feel at times like the construction of history itself: sometimes logical and fair-minded, but just as often idiosyncratic or skewed.”[27]

Joseph Smith in the National Portrait Gallery

Joseph Smith’s portrait was included from the very beginning of the National Portrait Gallery. His portrait’s inclusion is related to the history of the NPG’s 1968 opening, which was limited by funding and largely based on loans. Based on a request from the NPG staff, in 1968 Wallace B. Smith (the then president of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints) loaned the original Rogers portrait of Joseph Smith for the gallery’s grand opening. [28] Lewis McInnis, a member of the curatorial staff at the NPG, received the painting from Wallace Smith. In an unpublished manuscript provided to the author, Ronald Romig and Lachlan Mackay tell the story of what happened next:

After [the] return [of the original Rogers portrait] to Independence in December of 1968, the National Portrait Gallery made a proposal to provide the RLDS church a copy of the portrait of Joseph in exchange for the original. As an alternative, the National Portrait Gallery agreed to accept a sensitively done copy of the portrait, if the RLDS church would fund the project. After a group of members of the Washington, D.C., Congregation responded to the challenge and raised the funds, a copy of the original was produced by artist Adrian Lamb of Washington, D.C. On 14 November 1971, President W. Wallace Smith presented the Lamb copy to the National Portrait Gallery.[29]

In other words, the National Portrait Gallery wanted Joseph Smith’s original Rogers painting and offered to pay for a duplicate to replace it for the RLDS Church. The RLDS Church did not accept that offer and the NPG, it seems, turned the tables, placing the burden on the RLDS Church to fund a new portrait if Joseph Smith’s portrait was to be included in the NPG’s permanent collection. Those who see Joseph Smith today on permanent display in the NPG are indebted to generous, forward-thinking members of the RLDS Church in 1971 who paid to have this replica portrait of the Prophet produced.

Thus the painting in the National Portrait Gallery on permanent display is not the original 1842 painting attributed to Rogers, nor copies made by the RLDS Church in 1899 nor the 1950s, but rather it is a reproduction of the original Rogers image and was reproduced in 1971 by an artist named Adrian Lamb.

Artist Adrian Lamb

Adrian Lamb (1901–88) was born in New York City and studied at its Art Students League in the mid-1920s. He also studied art at the Julien Academy in Paris, completing his studies in 1929. Afterward he traveled to England and other European nations to practice, refine, and employ his capacities as a portrait artist.[30] Lamb became successful not only as an original artist but also as an artist with the technical ability to reproduce popular portrait paintings. For example, Lamb’s paintings are on display at George Washington’s Virginian estate, Mount Vernon. Lamb reproduced English painter Robert Edge Pine’s portraits of Washington’s grandchildren and John Trumbull’s portrait of Washington at the victory in Yorktown.[31]

Lamb’s portraits are found in many collections, including in collections from the State Department, the National Gallery of Art, The White House, the U.S. Naval Academy, Harvard University, and the Supreme Court of the United States.[32] Lamb was selected as the artist to paint Daniel Webster’s portrait in the Senate Reception Chamber.[33] Lamb also has multiple paintings in the National Portrait Gallery, including portraits of John Pierpont Morgan Sr., John D. Rockefeller Sr., and Theodore Roosevelt. When he died of a heart attack at eighty-seven, Lamb was prominent enough that his death was announced in the New York Times[34] and Chicago Tribune.[35]

Chief NPG Curator Brandon Fortune said, “Adrian Lamb was a well-regarded artist in New York who made several copies for the museum, including the painting of Joseph Smith, which was a copy of a painting owned by the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in Independence. He made the copy at the request of a private donor.”[36] Lamb’s reproduction painting of the Rogers portrait was done with oil on canvas, is 33 × 29 inches in size, and was completed in 1971.

Comparing the Rogers and Lamb Portraits

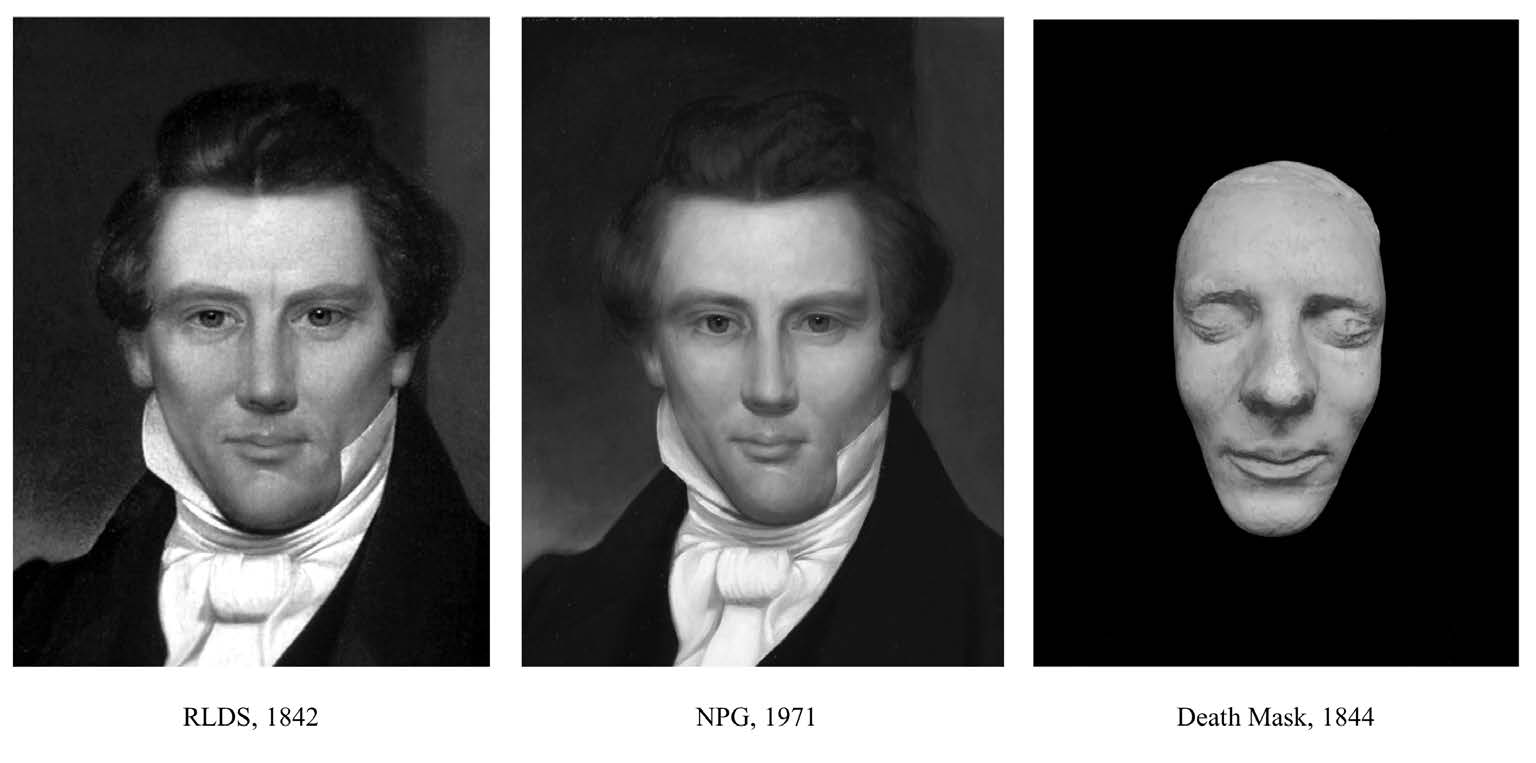

When comparing the original Rogers painting with Lamb’s National Portrait Gallery reproduction, the skill used in Lamb’s portrait is evident. Joseph’s pose, the right hand up with its wedding ring, the folds of the clothing, the background landscape with its dark and brewing sunset, Joseph’s pompadour hair, and his high upturned collar are all faithfully reproduced. It is difficult to detect substantial differences in these particulars. Although Adrian Lamb was a gifted technical reproduction artist, however, inconsistencies are introduced almost any time a reproduction is made. This is particularly true in the finer facial features. In general, Lamb’s NPG reproduction of Joseph Smith makes his facial features thinner. Joseph’s nose is narrower than the original in Rogers’s portrait. Thus Joseph’s eyes are closer together (since the outside of the nostrils generally line up with the inside of the eyes on the average human face), and therefore his mouth is slightly smaller (since the edges of the mouth generally line up with the middle of the eyes). Joseph’s forehead is higher in Lamb’s reproduction, as is Joseph’s hair. Also, Joseph’s nose appears slightly longer, and his cheekbones are lower in Lamb’s reproduction. All these small changes add up to show noticeable differences between the original and the reproduction, which are especially prominent to the trained eye.

These subtle changes between the Rogers original and the Lamb National Portrait Gallery reproduction are compounded by the fact that the original Rogers portrait differs from the Maudsley life profile drawings of Joseph Smith and from Joseph’s death mask. According to Junius F. Wells’s later reminisce of his visit with Emma Smith in 1875–76, when Wells asked Emma “if it [the RLDS portrait] were a good likeness of the Prophet,” Emma responded, “No. He could not have a good portrait—his countenance was changing all the time.” Wells then asked Emma what Joseph thought about this portrait of himself, to which Emma reportedly responded, “I can tell you that, for I asked him, and he said: ‘Emma that is a nice painting of a silly boy, but it don’t look much like a Prophet of the Lord!’”[37]

Figure 4. Side-by-side comparison of the Community of Christ, NPG, and death mask images of Joseph Smith. Photos by author.

Figure 4. Side-by-side comparison of the Community of Christ, NPG, and death mask images of Joseph Smith. Photos by author.

As Ephraim Hatch, author of Joseph Smith Portraits, writes about the Rogers original, “Either Joseph was not the model, or if he was, the artist was not very accurate [when compared to the death mask]. The mouth of the subject in the painting is too small, the upper lip is not high enough, the nose is too narrow at the base, and the eyes are too close together.”[38] In other words, the Rogers original is narrower in the nose, eyes, and lips than the death mask, and the Lamb NPG reproduction is narrower in those same areas than the RLDS Rogers original. There’s a double narrowing of Joseph’s features in the Lamb NPG portrait, as can be seen in figure 4.

Conclusion: Joseph’s Likeness in the NPG

Although there are some notable facial differences between the death mask of Joseph Smith and the Rogers original, Romig and Mackay note, “Joseph Smith III, and successive RLDS leaders . . . [expressed] belief that the oil portrait was the most authentic representation of Joseph Smith, Jr. . . . Its continuing acceptance may relate in some sense that, as a result of the artist’s evident skill, the portrait captures a portion of the emotional feel of Joseph’s character.”[39] I agree. While Maudsley’s profiles may be more consistent with the outline of the death mask, Maudsley’s images are more static stylized caricatures than true portraits that attempt to capture the spirit of individuals. Like the death mask itself, Maudsley’s images can lack the charisma and inspiration of Joseph that the Rogers portrait seems to carry. Similarly, although the Lamb NPG reproduction differs more narrowly in Joseph’s facial features from the Rogers original, it seems to similarly convey a strong spirit. Most notably, the characteristic unconscious smile of Joseph Smith,[40] seen in the Rogers original, is also captured in Lamb’s NPG reproduction. Many are unaware there is even a difference between the Rogers original and the Lamb NPG reproduction, thinking the NPG is the actual nineteenth-century original. Good portraiture, even if at times not precisely accurate, aims to communicate the potency of a person. There is a difference between a picture and a likeness. Most great paintings of Jesus fall into this category: they may not be historically accurate (such as Rembrandt’s Dutch model or Del Parson’s American one), but the artist represents the Redeemer and communicates the Christ to the viewer.

Noting my admitted bias toward Joseph Smith’s role in American history, it is remarkable that the Joseph Smith portrait hangs in a cherry-orange frame on a prominent wall in NPG’s permanent display, staring out at 1.3 million viewers who pass by him annually. The hall of “American Origins,” where Joseph’s portrait is located, is surrounded by authors, inventors, and educators who typically get much more wall space than prophets and preachers. Joseph is displayed near Washington Irving, Alexander Graham Bell, Samuel Morse, Thomas Edison, Frederick Douglass, Isaac Singer, Ira Aldridge, and Walt Whitman. Out of fourteen hundred images on permanent display, Joseph’s portrait is one of only a few religious leaders perpetually hung in the National Portrait Gallery.[41] Joseph’s inclusion in the NPG’s permanent display suggests a public recognition, as historian Robert V. Remini wrote at the 2005 “Worlds of Joseph Smith” conference at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC: “Mormonism is a very American religion . . . [which] has expanded, has been accepted, and has become part of the Christian tradition,” with the Book of Mormon being “a typically American story” that “Americans can easily appreciate.”[42]

Joseph’s NPG portrait accurately represents the gallery’s mantra of “poets and presidents, visionaries and villains, actors and activists whose lives tell the American story.”[43] All who are interested in the prophetic mission and influence of Joseph Smith upon America and the world are indebted to both the National Portrait Gallery and the Community of Christ for their efforts and foresight to include Joseph’s portrait in a permanent display.[44] As the effects of Joseph Smith’s prophetic mission continue, it is hoped that his portrait will remain permanently and prominently displayed in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery so that its visitors can consider his “significant contributions to the history, development, and culture of the people of the United States.”[45]

Notes

[1] “About Us,” National Portrait Gallery (website).

[2] In 2017, 1.3 million people toured the portrait gallery, https://

[3] Leon Alberti, On Painting (1435).

[4] Joanna Woodall, Portraiture: Facing the Subject (Oxford: Manchester University Press, 1997), 1–2.

[5] As cited in David McCullough, John Adams (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 638.

[6] Adams sat for portraits by Benjamin Blythe in 1766 (when Adams was only thirty), Mather Brown in 1788, John Singleton Copley in 1783, John Trumbull in 1793, Gilbert Stuart in 1798, and again for Stuart in 1824 at the age of eighty-nine, just a year and a half before Adams died.

[7] Peter Grier, “The Semi-Secret History of Trump’s Andrew Jackson Portrait,” Christian Science Monitor, 9 February 2017.

[8] Terryl Givens, People of Paradox: A History of Mormon Culture (Oxford University Press, 2007), 181.

[9] Jill C. Major, “Artworks in the Celestial Room of the First Nauvoo Temple,” BYU Studies Quarterly 41, no. 2 (2002): 50.

[10] “Journal, December 1841–December 1842,” 125, The Joseph Smith Papers, https://

[11] See Don L. Searle, “Painting of the Prophet Is Probable Source of Likeness on Map,” Ensign, April 1985, 78.

[12] “Sutcliffe Maudsley Exhibit,” https://

[13] Glen M. Leonard, “Picturing the Nauvoo Legion,” BYU Studies Quarterly 35, no. 2 (1995): 96.

[14] “Journal, December 1841–December 1842,” 205, The Joseph Smith Papers. https://

[15] Sarah Jane Weaver, “What Did Joseph Smith Really Look Like?,” Church News, 6 December 1997.

[16] Community of Christ Apostle Lachlan Mackay says that based on his research, “We are quite comfortable going with ‘attributed to David Rogers.’” Email communication with the author, 9 August 2019.

[17] Junius F. Wells, “Portraits of Joseph Smith the Prophet,” Instructor, February 1930, 79.

[18] Junius F. Wells, Instructor, 79.

[19] Author S. Michael Tracy, in his book Millions Shall Know Brother Joseph Again: The Joseph Smith Photograph (Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2008), concludes, “It is our opinion after much study that the side view oil painting of Joseph and its companion portrait of Hyrum are done by the artist named ‘Brother Rogers,’” 21. See also William B. McCarl, “The Visual Image of Joseph Smith” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1962), who also concludes that “Rogers painted a profile view of the Prophet and his brother, Hyrum . . . [and] the artist of the front view portrait owned by the Reorganized Church cannot be determined,” 65, 68.

[20] Summarized from Ronald Romig and Lachlan Mackay, “Hidden Things Shall Come to Light: The Joseph Smith, Jr., Family Visual Record” (unpublished manuscript in the author’s possession and used with permission).

[21] National Portrait Gallery—Agency History,” Smithsonian Institution Archives, http://

[22] https://

[23] Erin Williams, “Beverly Jones Cox, Former Director of Exhibitions and Collections Management for the National Portrait Gallery, Reflects on Her Past 43 years with the Museum,” Washington Post, 13 June 2011.

[24] Email communication between Brandon Fortune and the author, 19 June 2019, cited with permission.

[25] Bob Thompson, “Face Off,” Washington Post, 13 June 1999.

[26] Thompson, “Face Off.”

[27] Thompson, “Face Off.”

[28] Although the current exhibition label summarizing Joseph Smith’s life is expertly written, the first label prepared for the grand opening was unflattering: https://

[29] Romig and Mackay, “Hidden Things Shall Come to Light,” 3.

[30] “Adrian Lamb Biography,” askART (website).

[31] Mount Vernon Museum Collections, Mount Vernon Museum Official Website.

[32] “Adrian Lamb,” American Art Collaborative (website).

[33] “Daniel Webster,” United States Senate Art and History Archive (website).

[34] “Adrian S. Lamb, Artist, 87” (obituary), New York Times, 4 January 1989.

[35] “Adrian S. Lamb, 87, Portrait artist” (obituary), Chicago Tribune, 6 January 1989.

[36] Email communication between Brandon Fortune and the author, 19 June 2019, cited with permission.

[37] Wells, “Portraits of the Joseph Smith the Prophet,” 79.

[38] Ephraim Hatch, Joseph Smith Portraits: A Search for the Prophet’s Likeness (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1998), 50.

[39] Romig and Mackay, “Hidden Things Shall Come to Light,” 3, 1.

[40] Parley P. Pratt wrote of Joseph Smith, “His countenance was ever mild, affable, beaming with intelligence and benevolence; mingled with a look of interest and unconscious smile, or cheerfulness.” The Autobiography of Parley Parker Pratt (New York: Russell Brothers, 1874). 47.

[41] A search of “religious leaders” on the NPG website returns forty-six portraits such as Martin Luther, George Whitefield, Martin Luther King Jr., Ayatollah Khomeini (five of them), Dalai Lama, Billy Graham, Pat Robertson, and Brigham Young (seven portraits).

[42] Robert V. Remini, “Biographical Reflections on the American Joseph Smith,” The Worlds of Joseph Smith: A Bicentennial Conference at the Library of Congress, ed. John W. Welch (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2005), 23, 25.

[43] “About Us,” National Portrait Gallery (website).

[44] Over the years, the NPG has also collected other images of Joseph Smith (as well as Brigham Young), although they are not on permanent display: an 1847 lithograph of Joseph and Hyrum (NPG.79.159), an 1842 Oliver Pelton engraving copy of Sutcliffe Maudsley’s drawing (NPG.82.102), and seven images of Brigham Young (NPG.81.75; NPG.80.284; NPG.76.100; NPG.78.47; NPG.97.105; NPG.80.279; NPG.67.57).

[45] “About Us,” National Portrait Gallery (website).