Nicholas J. Frederick is an associate professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University.

The book of Ether recounts the story of the Jaredites, a group of postdiluvian refugees whose two-millennia occupation of the American “promised land” is described in a heavily edited form by Book of Mormon redactor Moroni. After centuries of highs and lows, the story ends with a duel to the death between two Jaredite leaders, Shiz and Coriantumr. Coriantumr prevails, and the final Jaredite lives out his days among the Mulekites, a rather melancholy end for such an epic story.

How did the Jaredites reach this point? How did this once-great people fall so quickly? According to the book of Ether, the pivotal moment occurs halfway through the narrative when readers are introduced to a young woman identified only as the “daughter of Jared” (Ether 8:8). Tasked with assisting her sorrowing father who likely was being held captive, the daughter of Jared secures his release by encouraging him to utilize a series of secret plans to secure the help of a man named Akish, a relationship the daughter of Jared secures by dancing before him. Her plan is initially successful, as Jared obtains his release, but the long-term impact of her actions are nothing short of devastating. At four points in the narrative of Ether, the Jaredites suffer mass destruction (9:12; 9:26–35; 11:7–8; 14:10–31) owing to the continual reappearance of these secret plans reinstituted by the daughter of Jared. Whereas the Jaredites survive the first three mass destructions, the fourth ends up being their undoing, ending with Shiz and Coriantumr’s final encounter and the extinction of an entire civilization.

The daughter of Jared is the only female mentioned in a two-thousand-year history, and it is her actions that lead directly to the destruction of her people. Surely such a consequential figure demands further study. At the very least, her story raises rather uncomfortable questions about the role of women in the Book of Mormon and the patriarchal perspectives of its male authors. Unfortunately, the surprisingly scant amount of literature devoted to her seems to revolve around a single issue—her connections with the biblical (also unnamed) figure of Salome. In his book The Mormons, sociology professor Thomas O’Dea wrote that “the story of Salome is barely hidden in the dance of the daughter of Jared.”[1] In her biography of Joseph Smith, Fawn M. Brodie similarly criticized Joseph Smith for borrowing so many stories from the Bible, including that of Salome, who like the daughter of Jared “danced before a king and a decapitation followed.”[2] Hugh Nibley treated at length what he termed “the Salome Episode,” writing that the entire story was “highly unoriginal” and “anything but unique” and arguing that the name Salome stemmed from Babylonian priestesses known as salme. He noted that the account of the daughter of Jared “is quite different from the Salome story of the Bible” but is “identical with many earlier accounts that have come down to us in the oldest records of civilization.”[3]

More recent scholarship has continued the unquestioned trend of tethering these two figures together. Blake T. Ostler observes that “Herod’s oath to Salome, which resulted in the death of John the Baptist, parallels the plot of the daughter of Jared to entice a murderous oath from Akish.”[4] In a 1992 essay Todd R. Kerr notes (likely following Nibley) that “many Jaredite kings relied upon secret oaths and combinations to overthrow or preserve power, as illustrated in the ‘Salome Episode.’”[5] Dan Vogel, too, sees in the account of the daughter of Jared “obvious comparisons to Herod’s promise to Salome, who danced for John the Baptist’s head,”[6] as does Brant A. Gardner: “This story obviously resembles Salome’s dance for Herod, resulting in the beheading of John the Baptist” (Gardner then cites Nibley).[7] In a recent book Earl M. Wunderli refers to the episode as a “Salome-like story.”[8] Although the episode of the daughter of Jared dancing for Akish has received ample scholarly attention, the vast majority of its commenters automatically associate the daughter of Jared with the biblical Salome in a manner that, I will argue, does damage to both characters.

Ironically, whereas the Book of Mormon refuses to give the daughter of Jared a name, Mormon studies has given her a name, but it is the wrong one. She is not the biblical Salome, and the biblical Salome is not the daughter of Jared. Although both accounts involve a dance and a beheading, these connections do not exhaust the story of Jared’s daughter. On the contrary, much more remains to be said. This is not to say that there are not strong connections between the two women. But these connections are made, I will argue, at the expense of the text. It is a conception of the daughter of Jared that has been identified with a conception of Salome, and it is the gap between these conceptions and the textual details that I intend to critique. With that in mind, this study will proceed on two fronts. I will first compare the accounts of Salome and the daughter of Jared to highlight connections that go beyond the narrative action. Second, I will offer a solution to the puzzle of why these two women have become so closely intertwined in Book of Mormon scholarship, one that does not require us to reach back into the first century to find the daughter of Jared, but rather brings Salome into the nineteenth century.

Salome

Salome’s story begins with the imprisonment of John the Baptist. John had drawn the ire of Salome’s mother, Herodias, when he condemned her second marriage to Herod Antipas (her first husband was Herod Philip). As a result, Herod Antipas had imprisoned John but was reluctant to do anything further because he “feared” John (Mark 6:20). Yet Herodias had no such qualms about seeking John’s death. Mark tells us that she “would have killed him; but she could not” (v. 19), suggesting that Antipas stood in the way of her murderous intentions. Demonstrating a patience both calculating and shrewd, Herodias waited for the right time to strike against John and found it on Antipas’s birthday. At this point, Salome enters the scene, but readers should make no mistake—Herodias remains the prime instigator and mover of all subsequent events.

The key information about Salome herself comes in Mark 6:22:

And when the daughter of the said Herodias came in, and danced, and pleased Herod and them that sat with him, the king said unto the damsel, Ask of me whatsoever thou wilt, and I will give it thee.

Three words here need unpacking. First, the Greek verb Mark uses for “dance,” orcheomai, simply means “dance.” No restrictions should be placed on what type of dance this might be based on the verb itself. Second, the reaction of Herod and his audience to the dance is that it “pleased” them. The Greek verb aresko simply means “to please or accommodate.” This verb could refer to physical pleasure, which is how Paul uses it in 1 Corinthians 7. But it more broadly refers to any action that leads to satisfaction or contentment, such as “the saying pleased the whole multitude” in Acts 6:5, or Paul’s words in Romans 8:8 that “they that are in the flesh cannot please God.”[9] While some commentators have stated that Salome’s dance was “unquestionably lascivious”[10] or that she was “dancing the dance of prostitutes,”[11] such claims reveal more about the reader than they do about the text. As art and religion scholar Angela Yarber shrewdly observes, “In the same way that Herod bears the guilt if he is potentially aroused by the dance of a young girl, so too must the reader bear the guilt of assuming that the dance of a young girl must be sexual, provocative, or lewd in order to please her father.”[12] Finally, what of the “damsel” herself? The word Mark uses to describe Salome is korasion, which is the diminutive form of kore, or “girl.” Mark had used the same word in the previous chapter to describe the daughter of Jairus, who readers are told was specifically “of the age of twelve years” (5:42). All three of these facts must be kept in mind when analyzing the Salome account.

Herod, pleased with the dance of his stepdaughter, offers her anything “unto the half of [his] kingdom” (Mark 6:23). Salome seeks out Herodias and asks her mother what she should ask for. Herodias’s answer is not at all surprising: “the head of John the Baptist” (v. 24). One cannot help but wonder just how far in advance Herodias has planned out this occasion. Did she just happen to capitalize on the good fortune provided by her daughter’s dance and her husband’s rash response? Or did she intentionally send Salome to dance before Herod, knowing what her husband’s response would be, with the full intent of acting out her revenge? Either way, it is Herodias, not Salome, who bears the culpability for procuring the head of John the Baptist.

It is not hard to see why readers of the Book of Mormon have often connected these two stories. Both involve an unnamed daughter (“daughter of the said Herodias” is how Salome is described in Mark 6:22). Both involve a female performing a dance before a powerful male figure (Akish and Herod). Both involve demands for decapitation—one realized (John the Baptist), the other foiled (Omer, though his rebel son Jared is later beheaded).[13] Both involve revenge against a perceived injustice (John the Baptist’s denunciation of Herod’s marriage to Herodias and Jared’s removal from the throne) leading to captivity. And both involve the swearing of oaths with unfortunate consequences (the beheading of John the Baptist and the destruction of the Jaredites).

However, there are also four important differences between the two accounts. The first is that in Ether 8 the daughter of Jared is the primary actor; it is she who puts the evil ideas into her father’s head and dances before Akish. In Mark’s account Salome acts at her mother’s behest and presumably does not know that her dance will result in John’s death until her mother instructs her after the dance to ask for John’s head (see 6:24). She is as much of a pawn in her mother’s game as Herod is. Because of this, the daughter of Jared seems to occupy the position or role of both Herodias and Salome, as if both figures were collapsed into one Jaredite female. A second major difference is the audience of the dance: Salome dances for her father and his friends, while the daughter of Jared dances for a potential husband. The presence of Herod’s guests presumably ensures that Salome’s request will not be dismissed, an action that would likely have caused Herod to lose face. The daughter of Jared, in the same fashion, has exactly the audience she requires. This leads to a third major difference, the nature of the request. Herod is clearly uncomfortable offering up John’s head, but he has little choice—his promise must be kept. Akish appears completely comfortable with the request to carry out the murderous plot, as are, one assumes, both Jared and his daughter. Finally, a fourth major difference is the nature of the dance itself. The daughter of Jared’s dance is prefaced by Moroni’s statement that Jared’s daughter was “exceedingly fair,” suggesting a likely sensual element to her dance, one that is expected to appeal to Akish and that will lead to his matrimonial request. While there is nothing in the text to suggest a salaciousness to the dance itself, it does appear designed to highlight the woman’s physical attractiveness. In contrast, Salome is described simply as a “damsel” (Mark 6:22), and no mention is made of her physical appearance. Nor is there any suggestion that her dance was in any way seductive or erotic, only that it “pleased Herod” (v. 22). Again, to suggest without textual evidence that Salome’s dance contained a lascivious element or that it was, in the words of one scholar, “hardly more than a striptease” is to surely go beyond the mark.[14]

Once these substantial differences come into view, readers can see that there is a larger gap between the two texts than scholars have usually hinted. To reiterate, the daughter of Jared is not the biblical Salome, and the biblical Salome is not the daughter of Jared. To simply label the daughter of Jared’s story as “the Salome episode,” as Nibley does, feels like a disservice to both figures. Yet at the same time there is enough in common between the two stories to warrant some consideration of Salome in a discussion of Ether 8. In answer to this intertextual puzzle, I suggest that her story is, in fact, vital to any study of the daughter of Jared, but, again, with this caveat—it is not the biblical Salome, but rather the nineteenth-century Salome, that matters.

To better understand the nineteenth-century Salome, we first consider the earlier images of her. Art from the Middle Ages and early Renaissance depict her as “innocent and submissive to her mother’s wishes.”[15] However, such depictions begin to change in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when “the image of Salome is transformed in Western art into a vehicle for depicting female beauty. She becomes slowly disassociated from the narrative of the scriptural story.”[16] Then, coinciding with the Victorian development of the femme fatale, the Salome story is “quickly exaggerated.”[17] Rather than the young, seemingly asexual girl who seeks to please her father and obey her mother, scholars and artists in the nineteenth century developed a Salome who, while still being depicted as young, was overly sexualized, even bordering on psychotic. Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, a professor of religious art and cultural history, summarizes the reasons behind this transformation:

In the nineteenth century, with the evolution of the romantic movement, there was a revival of interest in religious themes in art, literature, and music, although not always for spiritual purposes. In fact, by the end of the nineteenth century, the image of Salome erupted into one of the most popular themes of symbolist painting. With the development of the femme fatale, the classical figures of Helen of Troy, Cleopatra, and Medusa were rediscovered in conjunction with the apocryphal heroine, Judith, and the scriptural dancer, Salome.

However, this Salome was like no Salome seen before in either the visual arts or liturgical dance. She becomes the archetypal image of woman as the evil and destructive force whose sexuality, if not her very existence, threatened the lives of men.[18]

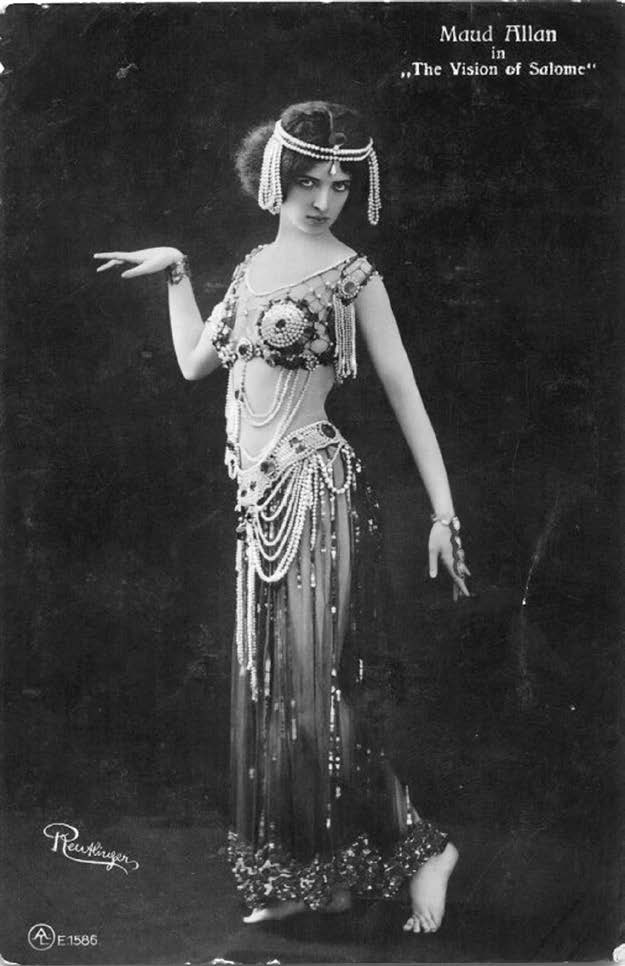

Maud Allan, who starred in the 1906 production of Vision of Salomé, became famous for her rendition of the “Dance of the Seven Veils” and was a major part of the “Salomania” movement in the early twentieth century. Postcard print, circa 1908. Public domain.

Maud Allan, who starred in the 1906 production of Vision of Salomé, became famous for her rendition of the “Dance of the Seven Veils” and was a major part of the “Salomania” movement in the early twentieth century. Postcard print, circa 1908. Public domain.

An early stage of this more sexualized portrayal can be seen in the work of Adam Clarke, an eminent theologian and biblical scholar who wrote a New Testament commentary that was published in England in 1810 and in America in 1824. Of Salome, Clarke wrote the following with obvious disdain:

This extravagance in favor of female dancers has the fullest scope in the east, even to the present day. M. Anquetil du Perron . . . gives a particular account of the dancers at Surat. This account cannot be transcribed in a comment on the Gospel of God, however illustrative it might be of the conduct of Herodias and her daughter Salome: it is too abominable for a place here.[19]

Salomé, by Henri Regnault, 1870. Oil on canvas. Public domain

Salomé, by Henri Regnault, 1870. Oil on canvas. Public domain

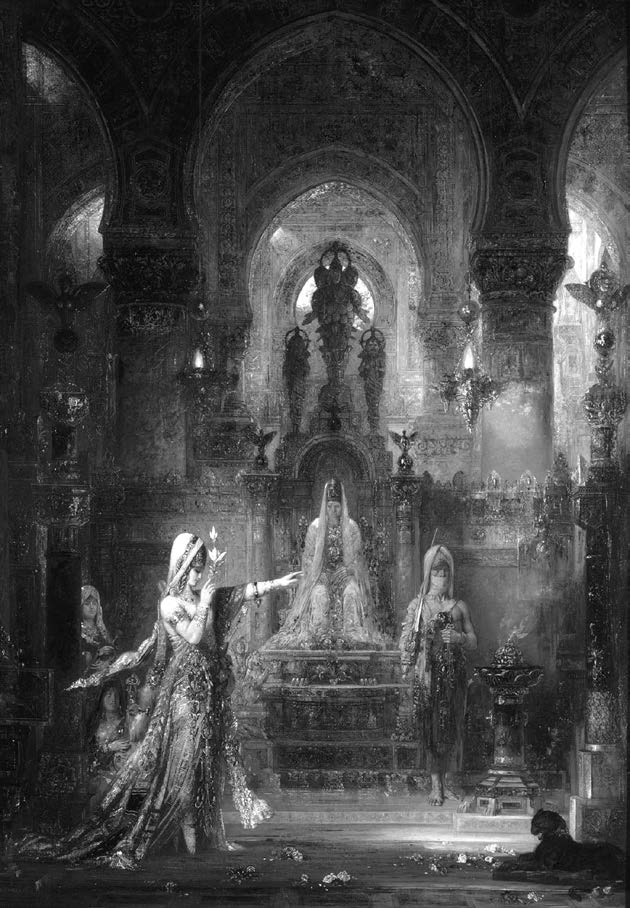

By the middle of the nineteenth century, artistic depictions of Salome were becoming popular. Two artists, Gustave Moreau and Henri Regnault, depict a Salome who appears before Herod as a dancer both erotic and exotic. In Moreau’s famous 1876 painting Salome Dancing before Herod, Salome appears with her hair veiled but her body openly on display as she provocatively approaches Herod. By the time of his death, Moreau would paint over one hundred images of Salome, each one presenting her as “a woman in slink garb, her disheveled hair piled upon her head like that of a courtesan, parts of her body previously hidden . . . now exposed and awaiting a lusty gaze.”[20]

Salome Dancing before Herod, by Gustave Moreau, 1876. Oil on canvas. Public domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Salome Dancing before Herod, by Gustave Moreau, 1876. Oil on canvas. Public domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This sexualized version of Salome became popular among the literati of the nineteenth century as well, especially as the end of the century drew near. In 1891 Oscar Wilde’s play Salome sexualized not only Salome’s dance but also her relationship with other major characters from the biblical episode. In addition to her overt sexuality on display during the famous “dance of the seven veils,” his Salome harbored a deep attraction to John the Baptist.[21] Wilde’s play served as inspiration for Richard Strauss’s opera Salome, which accentuated the wantonness of Salome, ending the play with her being crushed to death as she kisses the decapitated head of John the Baptist. In 1907 Strauss’s opera premiered in New York. By 1908 a reporter would state that “the country is Salome mad.”[22] The period between 1907 and 1910 in America has been termed a time of “Salomania,” when the American public found itself both fascinated and disturbed by the risqué dancer who died cradling John the Baptist’s head. This transformation of Mark’s innocent “damsel” into an erotic femme fatale not only grew more pronounced over the course of the nineteenth century, but it cemented itself as the dominant popular interpretation of the biblical Salome for the rest of the twentieth.[23]

The Daughter of Jared

Ether 8 finds the Jaredite nation, as is common in the book of Ether, in a state of political flux. The Jaredite king Omer had been overthrown and imprisoned by his rebellious son Jared. Jared’s brothers successfully turned the tables, instigating a coup that led to Jared’s presumed house arrest or imprisonment and the freedom of his father. Jared, Moroni tells us, wastes away in captivity, “exceedingly sorrowful because of the loss of his kingdom” (Ether 8:7). At this point the daughter of Jared appears. Moroni gives us two key pieces of information. First, she is “exceedingly expert” (v. 8). Webster’s 1828 dictionary defines expert as “skillful; well instructed” and “having a facility of operation or performance from practice.”[24] Whatever her upbringing, the daughter of Jared has developed a savviness that has likely served her well in the past. A second key point is Moroni’s observation that the catalyst for the daughter of Jared’s plan was her witnessing “the sorrows of her father” (v. 8). While she may also have been motivated by the power and prestige that (one assumes) she would regain if her father’s authority were restored, we cannot overlook her sense of familial loyalty. One or perhaps both of these sentiments may be behind the statement that her plan was one whereby “she could redeem the kingdom unto her father” (v. 8).

In the next verse Moroni alerts readers to two additional qualities. First, she is “exceedingly fair” (v. 9). Again, Webster’s dictionary tells us that fair means “beautiful” or “pleasing to the eye.”[25] In addition to her astuteness, the daughter of Jared was also, apparently, physically attractive. Second, her rhetorical question to her father as to whether or not he had “read the record which our fathers brought across the great deep” (v. 9) betrays an education, one that has not simply taught her to read but also primed her to recognize the usefulness of what she has read in the current political climate. And what do these records reveal? “Behold, is there not an account concerning them of old, that they by their secret plans did obtain kingdoms and great glory?” (v. 9). Apparently the Jaredite records alluded to by Moroni in the beginning of his abridgment contained something of a handbook on acquiring power through secret or devious means, a method that appears to have originated with Cain (see v. 15; compare Moses 5:29–31). (Why anyone would write these things down or allow them to be accessible to potential political rivals is never discussed in the record as we have it. See Alma 37:27.)

However, since Jared is likely in some form of imprisonment and his daughter seems to lack requisite political influence, the means to carry out these secret plans requires a third party. The daughter of Jared has an answer for this as well. Grandfather Omer has a friend named Akish, and Jared’s daughter offers to dance for Akish, relying on her “fair” appearance to capture his attention to such an extent that he will desire to marry her. Jared will agree to the marriage, but only if Akish will deliver Omer’s head to him (see Ether 8:10). Akish arrives, Jared’s daughter dances, and, as predicted, Akish asks for her hand in marriage and is granted it, although, ironically enough, Omer’s head remains safely attached (see vv. 11–12; 9:3). Significantly, the nature of the dance remains unexpressed, though this has not stopped several authors and commentators from interpreting it salaciously as a dance of seduction.[26] This is certainly possible because of the emphasis on the daughter of Jared’s being “fair” and the expected result being marriage, but, crucially, the text is opaque on this point.

After her dance, the daughter of Jared departs from the narrative, never to be heard of again. Unfortunately, her actions result in nothing but tragedy for her family. Her father, Jared, is appointed king but is subsequently betrayed by Akish and murdered “upon his throne” (Ether 9:5–6). Akish imprisons his son until he wastes away and dies (see v. 7). Another son of Akish flees to his great-grandfather Omer, and the subsequent battle results in the death of “nearly all the people of the kingdom” (v. 12), leaving only those who fled with Omer. The immediate story ends where it began, with Omer in charge, but the introduction of secret combinations will have devastating effects on the Jaredites. Moroni feels strongly enough about the daughter of Jared’s introduction of secret combinations that he spends the rest of Ether 8 offering a morality lesson on the negative effects of such organizations, warning latter-day Gentiles that they will suffer “overthrow and destruction if [they] shall suffer these things to be” (8:23). The remainder of Jaredite history will see the nation approach a collapse owing to secret combinations, only to find themselves spared through the Lord’s mercy—at least until the final encounter between Shiz and Coriantumr, at which point “Satan had full power over the hearts of the people” (15:19).

The Daughter of Jared, by James H. Fullmer. Courtesy of the artist.

The Daughter of Jared, by James H. Fullmer. Courtesy of the artist.

So what, then, can be said about the daughter of Jared based solely on the text of Ether 8? She appears to be, first and foremost, a political mover, possessing a savvy awareness of her current situation and what needs to happen to reverse it. This awareness is linked in some way to her education. She either has read or had relayed to her the account of secret combinations early in humanity’s history and recognizes how to apply the lessons of history to her time and circumstance. She appears to have genuine affection for her father, or at least sympathy for his presumed imprisonment. How that imprisonment directly affects her is not mentioned but is likely a strong motivating factor. One wonders if it is perhaps this link between father and daughter that causes Jared to take her advice in the first place. She is certainly physically attractive and does not appear to be beyond using her beauty to obtain her goal. Unfortunately, the text is also ambivalent about issues crucial to ascertaining her moral center. Is she fully aware of the evil she will unleash? Does she care? Do the ends (her father’s release from prison or house arrest and reenthronement as king) justify the means? Is she shortsighted or playing a long trick? Do her actions betray political ambition or filial loyalty?

Finally, something must be said about her role after she instigated the plot to kill Omer. Did Akish continue to act on her advice, as Nibley speculates, or does her disappearance from Moroni’s text reflect a similar disappearance in respect to the affairs of the royal court?[27] Nothing is said of her objection to either her father’s assassination by her husband or her son’s death, also at the hand of her husband. Did she live to regret her decision to engage Akish? Was she even around when he was killed? Intentionally or not, Moroni has positioned the daughter of Jared as the archetypal successor to the biblical Eve. Through the act of introducing forbidden knowledge to a complicit male partner, the daughter of Jared catalyzes the “fall” of the Jaredite nation.

Whence the Daughter of Jared?

What, then, can we say about Ether’s narrative and the woman who stands at the pivot point? Without a doubt, I think we can say that the daughter of Jared serves as the femme fatale of the Book of Mormon. She literally brings destruction to all those around her—her father, her family, and eventually her nation. But which woman is she—the biblical Salome, the biblical Herodias, the modern Salome? On one hand, the presence of certain narrative connections leaves open the possibility that the daughter of Jared’s story was crafted with Salome’s story in mind. However, on the other hand, the several differences between the two stories complicate any straightforward claim of biblical plagiarism. We are left, then, with the following question: Whence the daughter of Jared?

If we are to insist on a biblical intertext for Ether 8, then, as I see it, there are really only two options. The idea that the biblical Salome is the direct analogue for the daughter of Jared simply does not work. These are two very different women in two very different circumstances. The first option, then, is to see the daughter of Jared as a coupling of both Herodias and Salome, a move that combines these two women into one remarkable figure. Yet even then the daughter of Jared is more Herodias than Salome. The dance itself is the only contribution of Salome to the daughter of Jared’s story. Everything else that comes to define the daughter of Jared—her political savvy, education, investment in conspiratorial models, status as new wife, and so on—derives more from Herodias than from Salome. The second option is to see Ether 8 drawing on the Salome story of the nineteenth century, with its aggressive and deviant Salome, the “quintessential devouring woman”[28] who would risk murder and destruction in order to accomplish her aims. This option has the benefit of propinquity, since the Book of Mormon was written and published amid the transformation of Salome’s image in popular culture. If the Book of Ether’s redactor sought a femme fatale to set in motion the events that would lead to the destruction of the Jaredites, he did not have to look very far.

Yet even these two solutions do not do the daughter of Jared justice. Rather than being likened to the temptress whose alluring actions lead directly to the death of John the Baptist, the daughter of Jared is depicted as calm, shrewd, devoted, knowledgeable, and self-sacrificing. She may be beautiful, but her beauty is one of her features; it does not define her. It is not her allure alone that is the catalyst for her people’s demise, but her supposed resourcefulness and political aptitude. I have to admit that it is somewhat tempting to propose a third solution, namely, that the Book of Mormon almost anticipates the wildly excessive and degenerate portrayal of Salome (and, for that matter, several other literary women) that was emerging around it during the nineteenth century and offering something more complex, although by no means perfect, in its place, pushing back against the misogyny of the Victorian era. From this perspective, the Book of Mormon could be seen in effect as possessing an uncanny intuitiveness or prescience, foreseeing a problem and positing an alternative understanding.[29]

In the end, readers of the Book of Mormon may not ever be able to fully resolve the questions surrounding the daughter of Jared. Indeed, contemporary readers are likely unable to evaluate her actions through a lens that is untainted by the modern portrayal of Salome, a portrayal that seemingly condemns all dancing maidens as provocative and oversexualized.[30] If, by chance, Oscar Wilde had never presented his “dance of the seven veils” and the wanton Salome of Richard Strauss had never been developed, would we interpret Jared’s daughter in a different light? Would those who so boisterously condemn the daughter of Jared do so if the conversation surrounding her focused more on her mind rather than on her body? To those questions I have no good answer. However, I do believe we can recover something of the daughter of Jared’s story if we remove what I perceive has been the largest roadblock, namely, the shortsighted move of viewing Ether 8 as merely a recapitulation of the Salome story. To view either of these characters as the product of nineteenth-century male fantasy ultimately does a disservice to both Salome and the daughter of Jared and the richness of their textual settings. If, however, we are going to insist that the daughter of Jared’s story and Salome’s story be read in conjunction with one another, we would be wise to clarify which Salome we are actually referring to.

Notes

[1] Thomas F. O’Dea, The Mormons (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957), 38.

[2] Fawn M. Brodie, No Man Knows My History (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 62–63.

[3] See Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert / The World of the Jaredites / There Were Jaredites [Provo, UT: FARMS, 1988], 207–10. An excerpt of Nibley’s argument as reprinted in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon (ed. Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch, Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002) contains a side heading, “Salome’s Intrigues,” added by the editor. Nibley mistakenly states that the daughter of Jared’s actions “got her grandfather beheaded” (p. 212), but Omer actually survives the plot against him and is later restored to the kingship (see Ether 9:1–3, 13–15), though Jared is beheaded (see 9:5).

[4] Blake T. Ostler, “The Book of Mormon as a Modern Expansion of an Ancient Source,” Dialogue 20, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 76.

[5] Todd R. Kerr, “Ancient Aspects of Nephite Kingship in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1, no. 1 (1992): 89n13.

[6] Dan Vogel, “Echoes of Anti-Masonry: A Rejoinder to Critics of the Anti-Masonic Thesis,” in American Apocrypha: Essays on the Book of Mormon, ed. Dan Vogel and Brent Metcalfe (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002), 310. In his essay, Vogel is attempting to analyze connections between Herod’s oath and Freemasonry.

[7] Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Fourth Nephi–Moroni (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 249–50.

[8] Earl M. Wunderli, An Imperfect Book: What the Book of Mormon Tells Us about Itself (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2013), 95.

[9] The Greek verb aresko “means simply ‘please’ or ‘accommodate,’ and does not suggest sexual overtones.” J. R. Donahue and Daniel J. Harrington, The Gospel of Mark (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2002), 199. Of the seventeen uses of this verb in the New Testament, only two of them appear in a context that could be sexual: 1 Corinthians 7:33–34, where the context is pleasing a spouse.

[10] William L. Lane, The Gospel of Mark (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1974), 221. In a rather humorous deconstruction of Salome’s dance, F. Scott Spencer writes, “It’s not unreasonable to surmise that little Herodias (Salome) pleased her father with an innocent little girl’s dance, much as young daughters today bring smiles to their fathers at ballet recitals (that’s my baby in the center with the perfect plié). Now to be sure, I give my budding ballerina a rose and take her for ice cream—no offers of half the kingdom (which wouldn’t be much anyway). But proud fathers, even Herodian ones, can be quite generous.” Spencer, Dancing Girls, Loose Ladies, and Women of the Cloth (London: Continuum International, 2004), 56.

[11] Robert A. Guelich, Mark 1–8:26 , vol. 34a of Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word Books, 1998), 132.

[12] Yarber, Dance in Scripture, 95.

[13] See Mark 6:27; Ether 8:10–12; 9:3, 5.

[14] Harry Eiss, The Mythology of Dance (Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars, 2013), 35.

[15] Barbara Baert, “The Dancing Daughter and the Head of John the Baptist (Mark 6:14–29) Revisited: An Interdisciplinary Approach,” Louvain Studies 38 (2014): 17.

[16] Yarber, Dance in Scripture, 90.

[17] Yarber, Dance in Scripture, 90.

[18] Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, “Scriptural Women Who Danced,” in Dance as Religious Studies, ed. Doug Adams and Diane Apostolos-Cappadona (New York: Crossroads, 1990), 103; emphasis in original.

[19] Adam Clarke, Commentary on the New Testament (n.p.: Ravenio Books, 2013), s.v. “Mark 6, Verse 23.”

[20] Yarber, Dance in Scripture, 90.

[21] For the progression of Salome toward femme fatale status in Wilde’s play in particular, see Tony W. Garland, “Deviant Desires and Dance: The Femme Fatale Status of Salome and the Dance of the Seven Veils,” in Refiguring Oscar Wilde’s Salome, ed. Michael Y. Bennett (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2011), 125–43.

[22] As cited in Susan A. Glenn, Female Spectacle: The Theatrical Roots of Modern Feminism (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 96. Glenn also provides a wonderful examination of the “Americanization of Salome” that followed in the wake of Wilde’s scandalous play (see pp. 96–125).

[23] While there is some disagreement as to the exact origins of the femme fatale trope (whether its origins were pre-nineteenth century or not), its function seems a little clearer. According to Susan A. Glenn, “Salome and her counterparts were misogynist and anti-Semitic fantasies and projections of feminine sexual excesses and moral degeneracy. While the Salome of the Bible was a girl who obeyed her mother’s desire for revenge, the Salome of Wilde and Strauss is a creature with a will of her own. As a ‘bestial virgin Jewess,’ Salome the headhuntress is Salome the castrator, the quintessential devouring woman” (Glenn, Female Spectacle, 97). For more on the origins and evolution of the femme fatale, see The Femme Fatale: Images, Histories, Contexts, ed. Helen Hanson and Catherine O’Rawe (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), especially 46–59.

[24] Noah Webster, ed., An American Dictionary of the English Language (New York: S. Converse, 1828), s.v. “expert.”

[25] Webster, American Dictionary, s.v. “fair.”

[26] Heather B. Moore calls the dance “one rehearsed for the express purpose of seduction” (Women of the Book of Mormon: Insights and Inspirations [American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2012], 83), while Dennis Gaunt writes that Jared’s daughter “danced seductively” (Bad Guys of the Book of Mormon [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2011], 201). George Reynolds and Janne M. Sjodahl write that her plan was to “dance and display her feminine charms” (Commentary on the Book of Mormon [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1973], 131). Hugh Nibley says nothing of the dance but refers to the daughter of Jared herself as “sinister” (Lehi in the Desert, 212).

[27] Nibley surmises that Akish subsequently acts “directly under her influence” after his ascension to the throne (Lehi in the Desert, 212).

[28] Glenn, Female Spectacle, 97.

[29] However, to argue for this position would be to seemingly ignore the problematic gender issues that are present not just in Ether but throughout the entire Book of Mormon. See Kimberly M. Berkey and Joseph M. Spencer, “‘Great Cause to Mourn’: The Complexity of the Book of Mormon’s Presentation of Gender and Race,” in Americanist Approaches to the Book of Mormon, ed. Elizabeth Fenton and Jared Hickman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 298–320.

[30] Ironically, this same interpretive problem faces those who attempt to recover a modern-day view of Salome: “As far as straight feminist readings of Salomé are concerned, I believe we have yet to see a convincing contemporary one that does not reduce Salomé to pure physicality. As we have seen, feminist-inflected texts since the 1980s now celebrate, instead of condemn, her aggressive, instinct-driven, excessive, orgiastic sexuality (Cave and Robbins), present her as the victim of sexual violence (Egoyan) or madness (Altman), or read her sentimentally through the romantic lens of star-crossed love (Saura). Perhaps, a progressive straight feminist reading of Salomé that goes beyond Wilde’s play and adapts Salomé to our own times is actually impossible in light of the heavy misogynist cultural burden the Salome figure has carried for almost two thousand years.” Petra Dierkes-Thrun, Salome’s Modernity: Oscar Wilde and the Aesthetics of Transgression (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011), 201.