A House of Faith: How Family Religiosity Strengthens Our Children

Brent L. Top and Bruce A. Chadwick

Brent L. Top and Bruce A. Chadwick, "A House of Faith: How Family Religiosity Strengthens Our Children," in By Divine Design: Best Practices for Family Success and Happiness, ed. Brent L. Top and Michael A. Goodman (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014), 223–255.

The Apostle Paul warned that “in the last days perilous times shall come” (2 Timothy 3:1–4). His prophecies of the wicked conditions that will prevail in the last days are being realized before our very eyes. All manner of sin—including violence, crime, fraud, drug and alcohol abuse, pornography, and sexual immorality—can be seen in society. The Savior also prophesied concerning the conditions of the world that will precede his Second Coming when he stated “iniquity [does] abound” (Joseph Smith—Matthew 1:30). The “fiery darts of the wicked” are particularly aimed at families (Ephesians 6:16). Parents find themselves in the midst of the battle against sin and often worry that their children, who are surrounded by it, may be yielding to temptations. They wonder what they can do to protect their families from this onslaught of wickedness.

It is not just the parents who worry and wonder. Youth on the front lines in this battle against the growing wickedness of the world also are troubled by the temptations and challenges they face every day. “My parents really have no idea how hard it is to be a teenager today,” one LDS high school student despaired. Another lamented the pressure he feels from his friends. He reported, “Almost all of my friends use alcohol and drugs and go to parties almost every weekend. Many are immoral and tell me how fun it is. When I tell them these things are against my religion, they make fun of me and call me names.” LDS youth realize they are in the thick of perilous things.

Although parents cannot isolate their children from every evil influence, opposition, or peer pressure, they can insulate them. What can we, as parents, do to provide such insulation? What must occur within the walls of our own homes to help our children gain the spiritual and emotional strength to be righteous and responsible in these challenging times? Prophets of God continually raise their warning voices and lovingly give us counsel on how to strengthen our families. In addition, social science research confirms such counsel and gives further insight into how we can be better parents. This chapter reports many of the results of a large study (perhaps the largest ever done among LDS youth and families) on the influence of religion in the lives of LDS youth, and offers practical suggestions on how parents can strengthen the religiosity of their children.

The Power of Religion in the Lives of LDS Youth

In the landmark book Soul Searching, authors Christian Smith and Melinda Lundquist Denton (2005) reported the finds of the National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR), the largest and most detailed study of religion in the lives of teenagers in the United States ever conducted. [1] In contrast to earlier scholars who argued that religion has little or no influence on the behavior of adolescents (Stark, 1984 [2] ; Hirschi & Stark, 1969 [3]), Smith and Denton (2005) found that “the empirical evidence suggests that religious faith and practice themselves exert significant, positive, direct and indirect influence on the lives of teenagers, helping to foster healthier, more engaged adolescents who live more constructive and promising lives” (p. 263). [4] The NSYR study also reports that religiosity is positively correlated with academic achievement, moral development, and community volunteerism and is negatively linked to delinquency, alcohol, tobacco, and drug use, as well as illicit sexual activity among youth. Princeton professor Kenda Creasy Dean (2010) in her book, Almost Christian, analyzed the NSYR study and concluded:

Teenagers who say religion is important to them are doing “much better in life” than less religious teenagers, by a number of measures. Those who participate in religious communities are more likely to do well in school, have positive relationships with their families, have a positive outlook on life, and wear their seatbelts— the list goes on, enumerating an array of outcomes that parents pray for. . . .

Highly devoted young people are much more compassionate, significantly more likely to care about things like racial equality and justice, far less likely to be moral relativists, to lie, cheat, or do things “they hoped their parents would never find out about.” They are not just doing “okay” in life; they are doing significantly better than their peers, at least in terms of happiness and forms of success approved by the cultural mainstream. . . . So it comes as no surprise that young people who reported positive relationships with parents and peers, success in school, hope for the future, and healthy lifestyle choices were also more likely to be highly committed to faith as well. (pp. 20, 47) [5]

The findings reported in the National Study of Youth and Religion are particularly interesting to Latter-day Saint parents. Although the number of LDS teens who were included in the NYSR sample was quite small, the researchers were clearly impressed with their devotion and behavior. In a chapter entitled “Mormon Envy,” Professor Dean wrote:

Mormon teenagers attach the most importance to faith and are most likely to fall in the category of highly devoted youth. . . . In nearly every area, using a variety of measures, Mormon teenagers showed the highest levels of religious understanding, vitality, and congruence between religious belief and practiced faith; they were the least likely to engage in high-risk behavior and consistently were the most positive, healthy, hopeful, and self-aware teenagers in the interviews. (p. 20) [6]

The results of this national study and the observations of these researchers confirm what we have found from studying Latter-day Saint youth and families for the past quarter of a century (Chadwick, Top, & McClendon, 2010; Top, Chadwick, & Garrett, 1999; Chadwick & Top, 1993). [7] , [8] , [9] Our studies have clearly established that religion is a significant factor directly affecting the attitudes and actions of LDS adolescents. Importantly, we discovered that the religiosity of their parents and the spiritual environment of the home were significant influences in the religious development of the youth. Just as religion matters in shaping the character and behavior of youth, parents matter in shaping the faith and devotion of their children. “The best way to get most youth more involved in and serious about their faith communities,” Smith and Denton (2005) wrote, “is to get their parents more involved in and serious about their faith communities” (p. 267). [10]

A Study of Faith and Family among LDS Youth

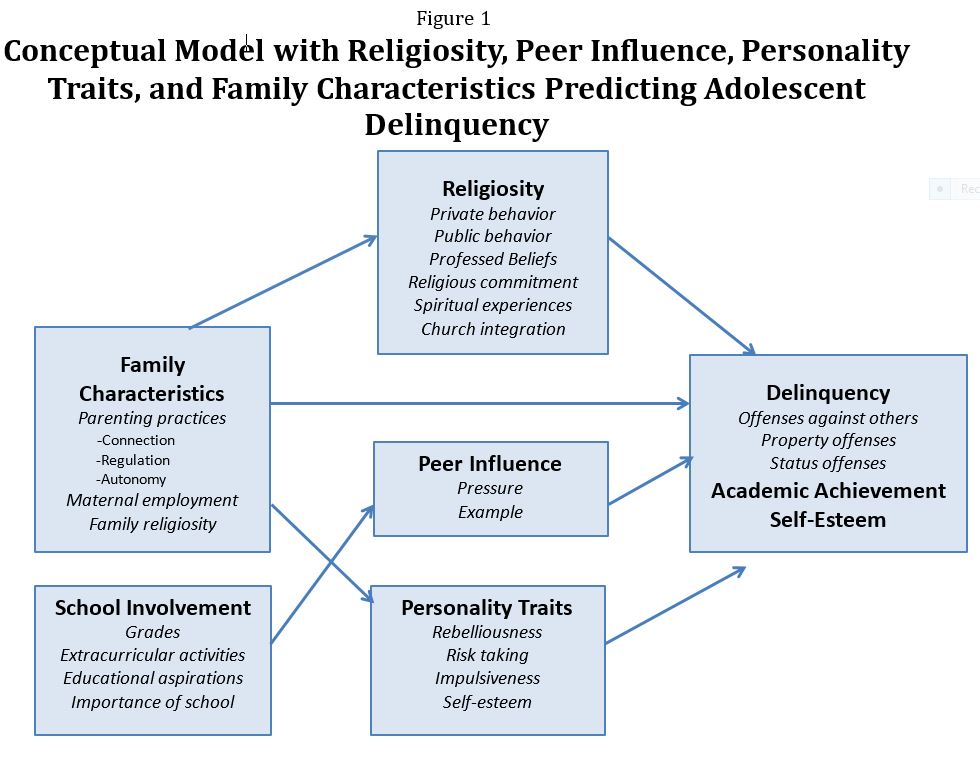

With the cooperation of the Church Educational System, over a 20 year period we surveyed over 5,000 LDS high school students, ages 14 to 18, living in different regions of the United States, Great Britain, and Mexico to test the relationship of religion and family with delinquency, academic achievement, and feelings of self-esteem. The study focused on these three behaviors because of their importance in the lives of teenagers. To ascertain the influence of religion and family on these behaviors, we included other important factors in a model of delinquency, including academic achievement and self-esteem. The theoretical model tested is shown in Figure 1. As can be seen, the model required religiosity and family to compete with peer influences, personality traits, and school involvement to explain delinquency. Structural equation analysis was used to test the model since it identifies the relative strengths of each of the factors in explaining delinquency, academic achievement, or feelings of self-esteem.

Obviously, we cannot report all of the results of these extensive studies in the limited pages of this chapter. Rather, we will share only a few of the major findings and discuss their implications for us as parents. Detailed theoretical, methodological, statistical information, and conclusions from these studies have been published in a variety of other venues over the past several years (see Chadwick, Top, & McClendon, 2010; Top & Chadwick, 2006; Top & Chadwick, 2004; Top, Chadwick, & McClendon, 2003; Top & Chadwick, 1999; Top & Chadwick, 1998; Top & Chadwick, 1993). [11] , [12] , [13] , [14] , [15] , [16] , [17]

Faith, Family and Delinquency

The influence of faith and family on delinquency among LDS youth was ascertained utilizing the theoretical model shown in Figure 1. The model allowed peers, religion, personality traits, school activities and family characteristics to compete in explaining delinquency.

Delinquent behavior included offenses against others, such as beating up other kids; property offenses, such as shoplifting and vandalism; and status offenses, including underage drinking, drug use, and premarital sex.

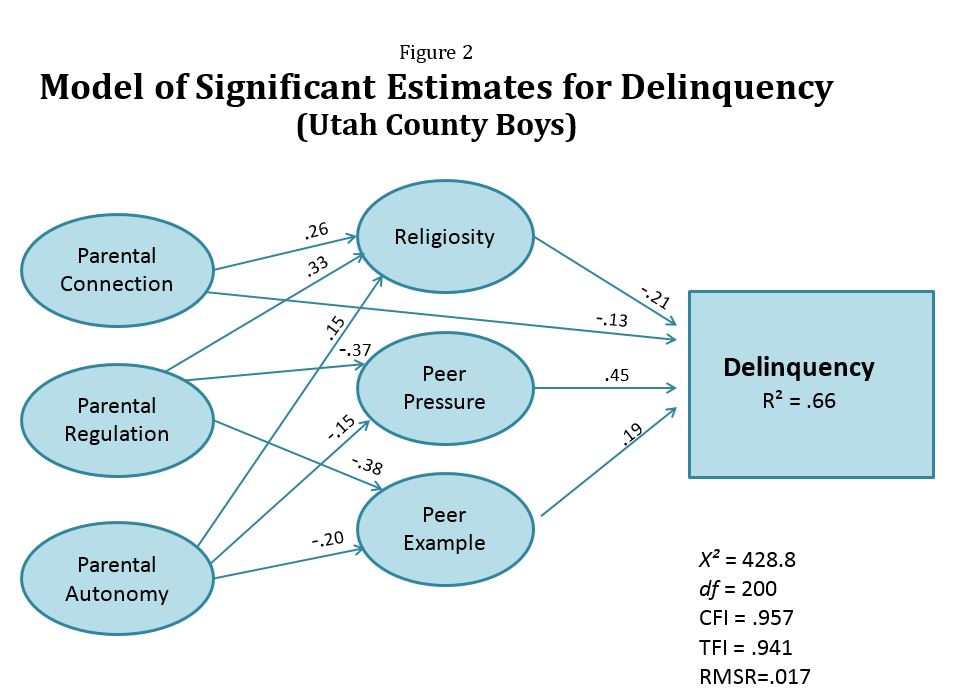

The results of the test of the model for young men living in Utah County are presented in Figure 2. Similar results were obtained for young men and young women residing in different regions of the United States, Great Britain, and Mexico.

In the figure we see that peer influences are the strongest predictor of whether an LDS teenager will engage in delinquent behaviors. We were certainly not surprised by this result. There is a large literature that has identified peer pressure as the single most significant factor predicting delinquency. What is important to note, however, is that religiosity is also statistically significant. The beta coefficient is -.21, which means that the greater the religiosity of the teenagers, the less they were involved in activities that are immoral, illegal, or improper. The model accounted for two-thirds of the variation in the delinquency among LDS young men.

At first we were disappointed to discover that only one family characteristic, parental connection—a combination of both a mom and a dad’s connection—was a significant predictor of delinquency in the multivariate model. Some social scientists have repeatedly contended that parents are largely irrelevant in accounting for the delinquent activities of their children (Harris, 2009). [18] The problem with these previous studies is that they examined only the direct effects of family on delinquency and neglected the indirect effects. As noted in Figure 2, parental connection (love and support), parental regulation (rules, obedience and discipline) and parental autonomy (parents’ acceptance of child’s feelings, opinions, and ideas) have strong impacts on their teens’ religiosity, resistance to peer pressures, and peer example. What these findings make clear is that parents who love and are concerned about their children; who set family rules, ascertain compliance, and discipline inappropriate behavior; and who allow their teens to develop their own sense of self have children with rather low delinquency.

Faith, Family, and Academic Aspirations and Achievement

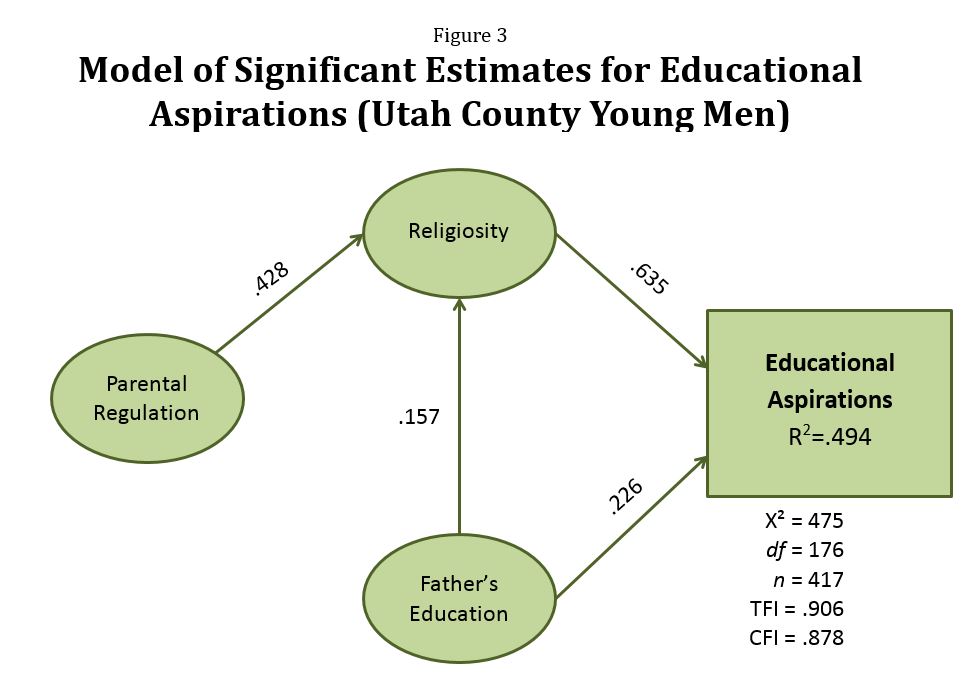

Loving parents want to help their children be happy, confident, responsible, and successful in life. Sometimes they go to great lengths to achieve that—buying the latest product that claims to help children get an “edge” in school or involving them in activities that “build” young people. These things are good, but as shown in Figure 3, which focuses on academic aspirations, we found one thing that is better—religiosity. Social science research has long noted that the educational level of a teen’s father is the strongest predictor of educational aspirations and accomplishments of adolescents.

The structural equation model presented in Figure 3 accounts for nearly 50% of the educational aspirations of the young men living in Utah County. As mentioned earlier, space constraints preclude presenting the various models predicting academic achievement and aspirations for LDS youth living in the different geographical areas. For our purposes in this chapter, we selected the model for Utah County young men because it is highly representative of the findings from the different populations.

Surprisingly, the strongest predictor of educational plans was the youths’ religiosity. Among LDS youth, religious beliefs, practices, and spiritual experiences combined into a measure of religiosity that was the strongest factor to emerge in the multivariate model. The father’s education was the only other factor to enter the equation. It should be noted that parental regulation made a strong indirect impact on educational aspirations through religiosity. The results for young women in Utah County and both young men and women in the other regions were very similar. There is no doubt that fostering their religiosity enhances LDS youths’ academic performance and desire for higher education.

Faith, Family, and Feelings of Self-Esteem

The last several years have witnessed great attention directed to studying the importance of self-esteem or feelings of self-worth among adolescents. Popular enthusiasm for self-esteem swelled to the point that many parents, school administers, and government officials came to believe that it was a social vaccine that increases desirable behaviors and decreases negative ones (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1992; Rosenthal, 1973; Hansford & Hattie, 1982). [19] , [20] ,[21] Mary Pipher (1994), a clinical psychologist who works with young women, detailed the negative impacts of the eroding self-confidence of young women in American society. [22]

Although fostering self-esteem seems to increase appropriate behavior among teenagers, some researchers have raised a serious concern. After conducting a thorough review of the self-esteem research, Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, and Vohs (2003) cautioned that parents, teachers, and others who have endeavored to raise self-esteem in young people may have unintentionally fostered narcissism in their children. [23] Young people thought to have high self-esteem may actually be self-absorbed and conceited. Narcissistic youth feel that they are so special they deserve special treatment by others and that the rules of society do not apply to them.

We were somewhat surprised to discover that LDS high school seniors have slightly lower self-esteem than a large national sample of high school seniors. There are two plausible possible explanations for these lower feelings of self-worth. One explanation is that the gospel and the Church place very high expectations and demands on its youth, which are difficult to accomplish, and failure to do so contributes to feelings of inadequacy. This lack of perfection is then expressed in response to the questions measuring self-esteem. The alternative explanation is that LDS youth are taught to be humble and avoid pride, so they are more modest praising themselves. We do not have the data necessary to test these two alternative explanations, but we hope LDS youths’ lower feelings of self-esteem are explained by the humility hypothesis rather than the perfectionism/

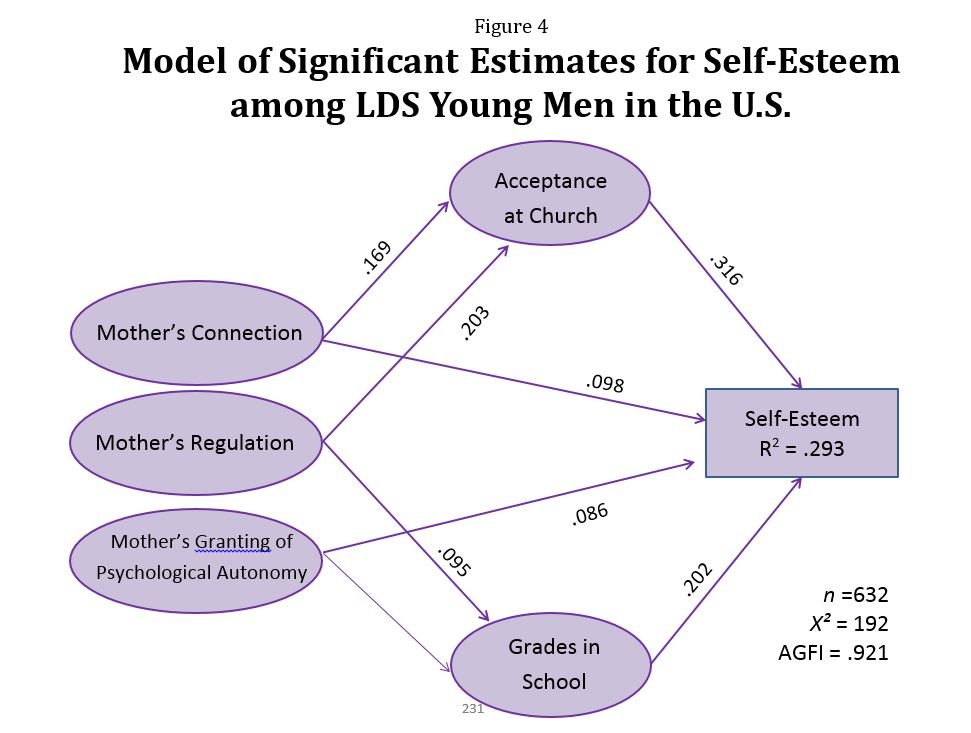

The results of the structural equation model predicting the self-esteem of LDS young men in the United States is presented in Figure 4. Acceptance at church produced by far the strongest impact on self-esteem for young men.

It is not surprising to find that feeling accepted is closely linked to how adolescents value themselves. What is unique to these LDS teens is where and with whom they feel comfortable. It is not acceptance by friends at school, but rather, it is within their wards and branches with leaders, teachers, and fellow members that acceptance had such a powerful relationship to feelings of self-worth.

Not surprisingly, grades earned in school also made a significant contribution to self-esteem. Success in school gives youths’ feelings of self-worth a boost.

Mothers’ connection also produced a weak direct effect on feelings of self-worth. We included only the teens’ mothers’ behavior in the model because the behaviors of mothers and fathers were so highly correlated that including both created major statistical problems. Thus, even though the model identifies mothers’ behavior, it represents the behavior of both parents. In addition, the indirect influence of mothers’ connection, regulation, and granting of psychological autonomy on self-esteem through the two direct factors should be noted.

The results of this complex analysis make it clear that parents and Church leaders really do matter in how teens feel about themselves. What leaps out from this analysis is that parents and leaders need to make sure teens feel a spirit of love, acceptance, and warmth in the home and in the community of Saints. Parents and leaders must work together to make sure youth feel welcome in seminary, institute, priesthood quorum meetings, Scout groups, young women classes, Sunday School, sacrament meetings, and other Church-sponsored activities. Such acceptance is important in helping young people develop positive feelings about themselves.

Religious Ecology versus Personal Religiosity

When we published the good news that religiosity was a powerful influence for good in the lives of LDS teenagers, some critics responded that we had misinterpreted our findings. Stark (1984) argued that the LDS youth we had studied living in Utah, Idaho, and Southern California were surrounded by a powerful LDS religious ecology. [24] Thus the theory was that youth had lower rates of delinquency and higher academic achievement because of the social pressures from their peers and from their entire community and not because of the religious principles they held.

In order to test the power of internalized religious principles against a religious ecology, we obtained data from samples of youth living in several regions of this country and Great Britain with differing religious ecologies. The communities ranged from a powerful religious ecology in Utah County to a low ecology in the Pacific Northwest and an extremely low ecology in Great Britain. We started with a sample of LDS high school students living along the East Coast because these teens were the only LDS students in their individual high schools. The results were almost identical with those obtained in the Utah-Idaho-California samples!

Critics responded that, while the LDS religious ecology was low, these East Coast students did live within a general Christian ecology that shaped their behavior. We asked our doubting colleagues where the lowest religious ecology in this country was. They readily identified the Pacific Northwest. Data were then collected from LDS youth in Seattle, Washington and Portland, Oregon. To provide an even stronger test of the religious ecology hypothesis, we collected data from LDS youth living in Great Britain. Space does not permit recounting the evidence of the low religious ecology in Great Britain, but these LDS youth lived in an extremely secular society and interacted with peers who were heavily involved in premarital sexual relations and alcohol and drug use.

The results for LDS youth living along the East Coast, in the Pacific Northwest and in Great Britain were very similar to those obtained in Utah. The religious ecology—where the adolescent lives and the religious culture of the community—did not matter nearly as much as did individual faith and religious conviction.

Internalized Religiosity

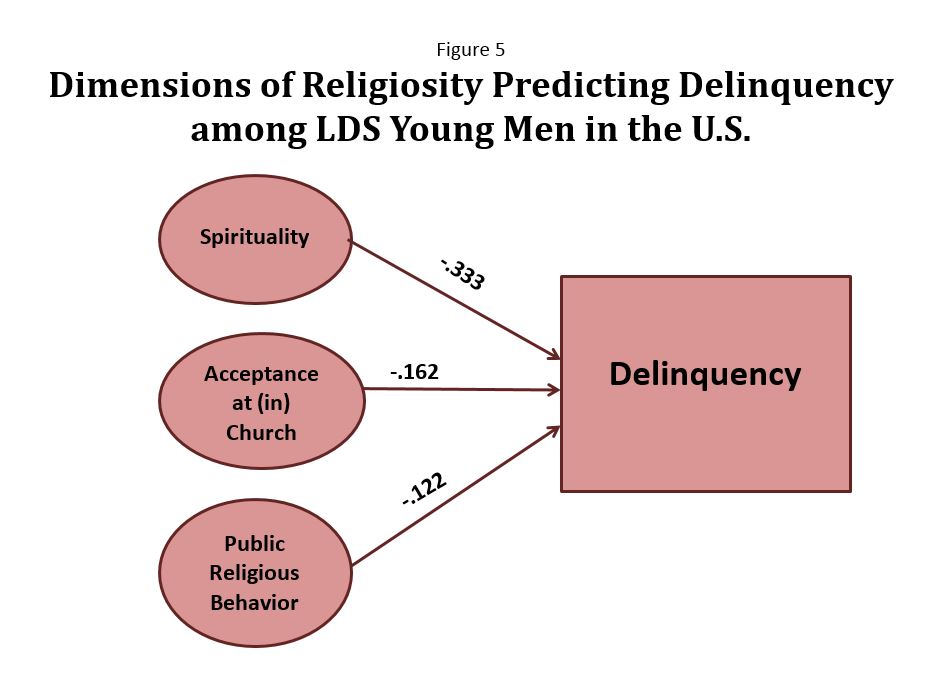

Most studies of the religion-delinquency connection have focused on affiliation and attendance, which are rather limited indicators of religious feelings and behaviors. In our study of LDS youth we examined five different dimensions of religiosity: professed religious beliefs, public religious behavior (attendance at meetings and involvement in church activities), private religious behavior (such as personal prayer and scripture study), spiritual experiences, and social acceptance at church. These different dimensions were included because we were convinced that internal feelings about the gospel are more important in the lives of teens than is mere attendance at church services.

Statistical tests were used to determine the relative strength of each of these factors. Because religious beliefs, private religious behavior, and spiritual experiences were so closely related, the confirmatory factor analysis combined them into one dimension of religiosity we called spirituality. Spirituality is the “stuff” of which a testimony of the gospel and commitment to the Church are made.

In model after model computed with different populations of young men and young women from different regions of the country and of the world, spirituality emerged as the strongest dimension of religiosity related to delinquency. To demonstrate the greater influence of spirituality as compared to public religious behavior and acceptance in church we computed a model in which only these three dimensions of religiosity competed to explain delinquency. As can be seen in Figure 5, each of these three dimensions of religiosity emerged as a significant predictor of delinquency. But the strongest factor by far was spirituality—the spirituality of the youth, the degree to which they had experienced and internalized the gospel into their lives—produced a beta coefficient of -.333. The negative number means an inverse relationship—the higher the spirituality, the lower the delinquency.

As mentioned earlier, what we anticipated would be important factors predicting delinquent behavior did not make a significant contribution in the multivariate model shown in Figure 2. Much to our surprise, family religiosity, which includes family home evening, family prayer, and family scripture reading, was not significant. What we learn from these results is that family religious practices and youth’s attendance at church meetings apparently do not in and of themselves counteract peer pressures to engage in unworthy behavior. Rather, these practices are means to an end, not the end itself—the practices merely encourage and facilitate individual religious commitment and personal conversion. Youth that have their own spiritual experiences and engage in their own religious practices such as daily prayer and scripture study, above and beyond involvement in family religious practice, have greater strength to resist temptation and increased determination to live righteous lives.

The results of our studies—not just the statistical findings, but also hundreds of comments by the youth themselves—validate the teachings of prophets of God given to the Church for generations: It is not enough to merely get our children into the Church; we must also make sure they gain a knowledge of the gospel and a personal testimony of its truthfulness. Our findings confirm what President James E. Faust (1990) declared:

Generally, those children who make the decision and have the resolve to abstain from drugs, alcohol, and illicit sex are those who have adopted and internalized the strong values of their homes as lived by their parents. In times of difficult decisions they are most likely to follow the teachings of their parents rather than the examples of their peers or the sophistries of the media which glamorize alcohol consumption, illicit sex, infidelity, dishonesty, and other vices. . . .

What seems to help cement parental [and Church] teachings and values in place in children’s lives is a firm belief in Deity. When this belief becomes part of their very souls, they have inner strength. (pp. 42–43) [25]

What Parents Can Do to Help Youth Internalize Gospel Principles

Youth should not be left on their own to make the gospel an integral part of their personal lives. While everyone must plant their own seed of faith, a fertile seedbed and nurturing environment is gained through a spiritually supportive family. Parents can do much to help their children internalize gospel principles. Elder M. Russell Ballard (1996) declared, “The home and family have vital roles in cultivating and developing personal faith and testimony. . . . The family is the basic unit of society; the best place for individuals to build faith and strong testimonies is in righteous homes filled with love. . . . Strong, faithful families have the best opportunity to produce strong, faithful members of the Church” (p. 81). [26] The responsibility of parents to create a home environment that fosters spirituality and internalization of religious teachings is, to Latter-day Saints, God-given and divinely mandated. The First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (1995) have declared: “Parents have a sacred duty to rear their children in love and righteousness, to provide for their physical and spiritual needs, to teach them to love and serve one another, to observe the commandments of God, and to be law-abiding citizens wherever they live. Husbands and wives—mothers and fathers—will be held accountable before God for the discharge of these obligations”(p. 102). [27]

From the results of our extensive study and from the anecdotal comments of hundreds of LDS teens and young adults, several important suggestions emerged as to how parents can specifically help their children make the gospel an important part of their lives. It is impossible to discuss at length all of these suggestions in this chapter. For our purposes here, we offer three general suggestions.

Practice What You Preach

The old adage “actions speak louder than words” is certainly true within the walls of a home. Nothing will undermine our efforts to create a spiritual home environment more than neglecting to practice what we profess. All that we teach as parents will seem hollow or trivial to our children if we don’t evidence our beliefs and values in a comprehensive way of life. To use the language of our kids, “We must walk the walk, not just talk the talk.” This doesn’t mean parents have to be perfect. We aren’t, and our children know it. They’re smart enough to realize that we have weaknesses and at times we may not be as good as we desire. Parents do serious damage, however, when they deliberately go against the very teachings and standards they expect of their children. It seems that our children have a special radar system that can detect not only parental hypocrisy but also insincerity. Although teens may not notice a lot of things we wish they would—like the clutter and chaos in their bedrooms or the lateness of the hour when they are having fun with friends—they are quick to observe parental hypocrisy or attempts to live a double standard. When it comes to having a “house of faith,” there can be no double standards.

If we want our children to have testimonies of the gospel, to internalize its principles and to live by high standards of purity and integrity, we must do the same. If we want them to be worthy to marry in the temple, we must strive to be temple worthy and demonstrate our love for the temple by frequent attendance. If we want them to study the scriptures and sincerely pray to our Heavenly Father each day, we need to do the same. If we want them to be committed to the gospel and actively involved in the Church, we must show them the way by our lives—by our activity in the Church and our faithfulness to callings and covenants. To do otherwise sends the signal to our children that the gospel we teach really isn’t all that important to us after all. As a result, they likely won’t take it seriously either. We can’t give what we don’t have! “We need to start with ourselves as parents,” President Henry B. Eyring (1996) declared, “No program we follow or family tradition we create can transmit a legacy of testimony we do not have” (p. 63). [28]

Teach the Gospel

In this dispensation the Lord has commanded parents to teach their children “the doctrine and repentance, faith in Christ the Son of the living God, and of baptism and the gift of the Holy Ghost by the laying on of hands. . . . And they shall also teach their children to pray, and to walk uprightly before the Lord” (D&C 68:25, 28). Failing to do so results in, as the Lord declared, “the sin be[ing] upon the heads of the parents” (D&C 68:25). This divine mandate has been reaffirmed by prophets in our own day. In a letter addressed to “Members of the Church throughout the World,” dated February 11, 1999, the First Presidency declared, “We call upon parents to devote their best efforts to the teaching and rearing of their children in gospel principles which will keep them close to the Church.” They further declared that “the home is the basis of a righteous life” and that no other agency, program, or organization can adequately replace parents in fulfilling their “God-given responsibility” of teaching the gospel (p. 80). [29]

It would be easy, in light of these strong statements, for us as parents to feel overwhelmed by this sacred obligation. Some of us may feel that we lack sufficient gospel knowledge to properly teach our children. Some of us may feel we lack adequate teaching skills. Some of us may have other concerns. All parents have inadequacies, but the Lord has given us the responsibility to teach the gospel to our children nonetheless. Fortunately, the Lord never gives responsibilities without also providing “a way for them that they may accomplish the thing which he commandeth them” (1 Nephi 3:7). The Church has provided us with inspired programs and counsel that can assist us in our responsibilities and make them far less intimidating. From our research, including hundreds of comments from LDS youth and young adults, we have found three simple things that parents can do to better teach the gospel to their children.

Hold Regular Family Prayer, Family Home Evening, and Family Scripture Study

“We counsel parents and children,” the First Presidency (1999) stated, “to give highest priority to family prayer, family home evening, gospel study and instruction, and wholesome family activities” (p. 80). [30] Even though the statistical results of our study showed no significant direct relationship between these family religious practices and delinquency, academic achievement, and feelings of self-worth, that doesn’t tell the whole story. As previously discussed, we found that personal spirituality and religious conviction of LDS youth are directly linked to lower levels of delinquency. Family religious practices such as family home evening, family prayer, and family scripture study promote religious internalization and thus impact adolescent behavior. There is a spiritual power in family religiosity.

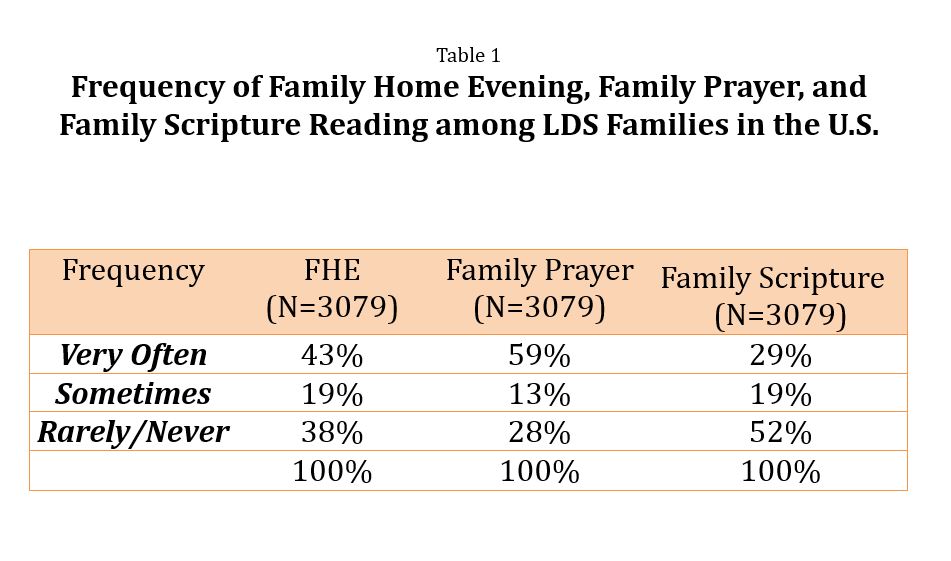

Despite the prophetic counsel to hold family religious activities, a surprising number of families do not avail themselves of the great blessings that family home evening, family prayer, and family scripture reading can yield. As can be seen in Table 1, only about half of the LDS families involved in our studies reported that they held regular family prayer and family home evening, and less than a third had regular family scripture study.

Perhaps every parent feels frustrated at times in trying to faithfully hold these family religious practices when the children are restless and nothing seems to be “sinking in.” The young people in our study made many comments that should be encouraging to parents. They readily admit that there is a more powerful influence in these practices than what may appear on the surface. These hindsight comments from the young adults we interviewed show the lasting influence of family religious practices:

I know that I was a pain in the neck of my parents when it came to family prayer and family home evening. But I am thankful now that they didn’t give up. It had more influence upon me than I was willing to admit at the time.

I pretended not to be listening when we had scripture study or lessons during family night, but more sank in that my parents thought. Even though my dad was inactive, he was always the one saying, “Time for family scripture reading” or “Prayer time.” That showed me that he still wanted what was best for his family. It really helped our family.

The study results, coupled with hundreds of anecdotal comments from youth and young adults, confirm what prophets of God have long taught: Testimonies are strengthened, gospel knowledge is increased, and greater love and harmony within the family result when parents faithfully attend to these family religious practices. When the family home evening program was first introduced to the Church, the First Presidency (1915) promised the Saints “great blessings” if they would diligently seek to “gather their boys and girls about them in the home and teach them the word of the Lord.” [31] Undoubtedly, these promises apply today just as much, if not more so, than in 1915, and not just with regard to family home evening. It applies to all aspects of teaching and rearing of children in gospel principles.

If the Saints obey this counsel, we promise that great blessings will result. Love at home and obedience to parents will increase. Faith will be developed in the hearts of the youth of Israel, and they will gain power to combat the evil influences and temptations which best them. (733–34) [32]

Teach Practical Applications of Gospel Principles

The Lord has commanded parents to teach their children to “walk uprightly before the Lord” (D&C 68:28). There are two dimensions to this sacred parental duty—first, to teach the doctrines of the kingdom, and second, to teach their children how to apply those doctrines to their daily lives. As one of the young adults in our study observed, “I don’t think parents teach the fundamental doctrines of the gospel enough—things like faith, repentance, and the Atonement and how these things work in daily life. Parents often teach doctrines and principles, but don’t specifically talk about the why and the how.”

Nephi spoke of “liken[ing the] scriptures” to ourselves (1 Nephi 19:23). This certainly applies to gospel teaching in our homes. Parents can do this by talking with their children about how the gospel can actually help us in our daily lives and apply it to dealing with specific temptations and challenges we face. An important way whereby we can teach practical application of gospel principles to our children is to ask them how they would apply or “liken” the gospel to their own unique circumstances. Practical application of the gospel can be a two-way street—we can share with our families how the gospel applies in our lives and learn from them on how they do the same.

One young woman in our study reported that her father would often talk to the children about challenges or problems he was having at work. “How would you handle this?” he would ask his family. Pretty soon a good discussion would ensue, focusing on how gospel principles solve life’s real problems. The young lady observed, “Now I realize he was helping us to see how the teachings of the gospel actually work in life, rather than asking us to solve his problems.” Youth are much more likely to live the standard of the Church when they know not only the doctrines but also why they should do as they are commanded, and what will be the practical benefits, right here and now, of living the gospel.

Discuss and Share Feelings about the Gospel at Times Other Than Sunday

A major challenge youth have to overcome in order to have strength to resist temptation is the tendency to view religion as merely a “church thing” or something that is done only on Sundays. This compartmentalization prevents them from seeing how the teachings of the gospel affect everyday lives and everyday situations. Seeing how the gospel is fully integrated into their parents’ lives will help children understand how it can permeate every part of their own lives. In fact, the word “religion” has its root in a Latin word ligare, which means “to bind,” “to connect,” or “to hold together.” It is the same root found in the word “ligament.” Religion exerts power in our families when it is fully attached to or connected with all aspect of our lives.

Not all opportunities to teach the gospel to our children occur on Sundays, Monday evenings, or during early morning scripture study. In fact, some of the most important gospel teaching moments may come at unscheduled or unexpected times. They may come when a daughter faces a difficult challenge at school or when a son is debating the merits of serving a mission—anytime a child is worrying, wondering, or questioning.

Seizing these teaching moments whenever they occur and talking about religious principles when needed shows our children that the gospel has everyday application. Often these informal discussions help our children to better connect the dots, so to speak, and see how the doctrines and principles of the gospel really fit together and apply to daily life. One young woman in our study made the following astute observation as to how informal gospel discussion can yield unexpected and unintentional, yet powerful, gospel learning experiences:

There are two places that I hold dear to my heart and see as great gospel learning places. This may sound strange, but they are my parents’ king-size bed and the kitchen table. We almost always ate dinner together, and there we would talk about our daily activities, but there was much more than that. We often would get into in-depth gospel discussions or talk about how we felt about something. Just these little things taught me so much. As for the bed—it had to be a king-size so all six of us kids could fit on it. This was a place where we could talk with Mom and Dad. I received so much comfort, guidance, and spiritual teaching there.

Help Your Children Come to Know for Themselves

The cement that holds gospel teachings in place in the lives of our children (as well as ourselves) is personal spiritual experience. As was cited previously, the most powerful component of religiosity on behavior is personal spirituality—feeling the Spirit in one’s own life and experiencing the fruits of gospel living. Two scriptural accounts, though not specifically teaching parenting practices, illustrate this principle well.

The first comes from the ministry of John the Baptist. His foreordained mission was to be an Elias—one who prepares the way for someone even greater. He did not merely draw disciples to himself with his teachings and testimony. Rather, because those who listened to him were inspired by his words and touched by his love, they accepted his direction to their most important relationship—a relationship with the Savior of the world. “He must increase,” John testified of Christ, “but I must decrease” (John 3:30).

As parents, we must be like John—preparers of the way for our children to come to know the Master for themselves. We can teach, love, nurture, strengthen, serve, and exemplify, but ultimately only the Savior can save. The religious environment of our home—teaching both by precept and example—ultimately must lead our children to him.

This leads to the second scriptural account that testifies of this—the account of Lehi’s dream of the tree of life (see 1 Nephi 8). We are familiar with the story and symbols of his dream: the iron rod, the strait and narrow path, the mists of darkness, the great and spacious building, and the fruit of the tree, which “was desirable to make one happy” (1 Nephi 8:10). From Nephi’s later commentary, we learn the spiritual meaning of the symbolic elements of the dream (see 1 Nephi 11–12). One particular element of the story, however, has particular application to parents. It is what Father Lehi says and does after he arrived at the tree of life and partook of its fruit.

And it came to pass that I did go forth and partake of the fruit thereof; and I beheld that it was most sweet, above all that I ever before tasted. Yea, and I beheld that the fruit thereof was white, to exceed all the whiteness that I had ever seen.

And as I partook of the fruit thereof it filled my soul with exceedingly great joy; wherefore, I began to be desirous that my family should partake of it also; for I knew that it was desirable above all other fruit.

And as I cast my eyes round about, that perhaps I might discover my family also. . . .

[And] I beheld your mother Sariah, and Sam, and Nephi; and they stood as if they knew not whither they should go.

And it came to pass that I beckoned unto them; and I also did say unto them with a loud voice that they should come unto me, and partake of the fruit, which was desirable above all other fruit. (1 Nephi 8:11–15; emphasis added)

Any loving parent can relate to Lehi’s desire that his family also partake of the love of Christ. Virtually every parent would do anything in their power to ensure that their children would partake of the fruit. Lehi did all he could. However, he understood that there are some things that parents cannot do.

Lehi exhorted his children “with all the feeling of a tender parent” (1 Nephi 8:37), but he could not compel his children to hold to the iron rod, come to the tree, and partake of its fruit. He could not eat the fruit for them or “force-feed” them or provide some special “short-cut” through the mists of darkness. He knew—and we must know also—that all people, including our own children, must come to the tree on their own. There is no other way to partake of the saving love of the Savior. What can we, as parents, do besides just desiring that our children come to know for themselves the love of God, the truthfulness of the gospel, and the sweetness of the Atonement of Jesus Christ? From our study and through years of observation and experience, we have found three specific things that parents do that are most effective in helping their children come to experience for themselves the blessings of personal testimony and living gospel principles.

Provide Opportunities for Spiritual Experiences

While real spiritual experiences cannot be manufactured or contrived, parents can provide opportunities and settings in which their children may more easily feel close to the Lord and the companionship of the Holy Spirit. In this way, youth are not limited to simply learning about the gospel and seeing it in action; they can actually experience it. Many young people in our study identified special moments—many of which were spontaneous and unexpected—when they felt an outpouring of the Spirit. One young woman told of an experience in which her family went to the temple and did baptisms for the dead for some of their ancestors. Afterward, she said her parents talked to the children about the importance of the temple: “They told us how much they loved the temple and how thankful they were to have us sealed to them,” she remembered. “We had heard these things before, but because of what we had just been doing as a family, their testimonies had a powerful impact on us.”

Others reported similar, strong spiritual feelings as they had father’s blessings, witnessed the blessing of a sick family member, performed meaningful service for those in need, or held impromptu testimony meetings. Sometimes simple things yielded the most profound spiritual feelings.

Encourage Personal Prayer and Scripture Study

If we were to identify one thing as the single most important factor in helping our children internalize gospel principles, it would undoubtedly be personal prayer. It is the catalyst for the development of all other spiritual traits and strengths. Those youth in our study who consistently prayed privately had significantly lower levels of delinquency, including immorality and drug and alcohol use. In contrast, those youth who didn’t live the standards of the Church and who engaged most frequently in delinquent behaviors, rarely if ever prayed privately. Ironically, however, even among this latter group, the majority reported that they participated regularly in family prayer. As important as family prayer, family scripture study, and family home evening are, they are, nonetheless, external religious activities. Personal prayer and individual scripture study are internal religious behaviors that can have even greater power in the lives of our children.

There are prophetic promises attached to those internal private religious practices. President Ezra Taft Benson (1977) promised the youth of the Church, “If you will earnestly seek guidance from your Heavenly Father, morning and evening, you will be given the strength to shun any temptation” (p. 32). [33] Likewise, he promised that regular study of the scriptures, particularly the Book of Mormon, will yield “greater power to resist temptation” and “power to avoid deception” (1988, p. 54). [34] Many of the young people in our study gratefully acknowledged the encouragement they received from their parents in this regard.

My dad always reminds me, “Say your prayers.” This reminds me that it is not enough to have family prayer. I must pray on my own.

I am so blessed now because parents encouraged me when I was young to pray and read my scriptures on my own. Reading the scriptures and having personal prayer are things not to be done without.

Encourage our Children to Gain Their Own Personal Testimony of the Gospel

Perhaps the most important component of the shield of faith is personal testimony and conversion. The results of our research confirm that those youth who have their own personal conviction of the gospel have fewer behavioral problems, have a stronger sense of self-worth, and do better in school. They possess an inner strength that enables them to resist temptation and stand firm against negative peer pressures. “I am satisfied . . . that whenever a man [or woman or youth] has a true witness in his heart of the living reality of the Lord Jesus Christ all else will come together as it should,” President Gordon B. Hinckley (1997) said. “That is the root from which all virtue springs among those who call themselves Latter-day Saints” (p. 648). [35] The comments of many of the young people we have surveyed through the years provide powerful witness to that fact:

I wish I had developed a strong testimony earlier in life. I found that [by] the time I had strengthened my testimony or experienced my personal conversion, I had already given in to many temptations which I regret to this day. I wish I had not acted “too cool” for the gospel and instead softened my heart so a testimony could have entered in.

A testimony of the Savior and the gospel’s truth is so necessary to resist temptation. In my eyes a testimony is the best prevention against Satan’s temptations and is the most important thing parents can teach.

My parents’ top priority was that we develop our own personal testimonies.

Because Satan targets our children at younger and younger ages, they must internalize the teachings of the gospel they receive at home and at Church by developing a meaningful relationship with God and testimony of the truthfulness of the Restoration sooner rather than later. It’s never too early, but it can become too late. We may be seeing the fulfillment of the prophecy uttered by President Heber C. Kimball (Whitney, 1967) in the mid-nineteenth century. His warning should echo in our ears and burn in our hearts as we daily strive to lead our children to God:

To meet the difficulties that are coming, it will be necessary for you to have a knowledge of the truth of this work for yourselves. The difficulties will be of such a character that the man or woman [or youth] who does not possess this personal knowledge or witness will fall. . . . The time will come when no man or woman will be able to endure on borrowed light. Each will have to be guided by the light within himself. If you do not have it, how will you stand? (p. 450) [36]

Conclusion

The religious environment of our homes plays a significant role in helping our children “put on the whole armour of God that [they] may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil” (Ephesians 6:11). President Boyd K. Packer (1995) taught:

The plan designed by the Father contemplates that man and woman, husband and wife, working together, fit each child individually with a shield of faith made to buckle on so firmly that it can neither be pulled off nor penetrated by [Satan’s] fiery darts.

It takes the steady strength of a father to hammer out the metal of it and the tender hands of a mother to polish it and fit it on. Sometimes one parent is left to do it alone. It is difficult, but it can be done.

In the Church we can teach about the materials from which a shield of faith is made: reverence, courage, chastity, repentance, forgiveness, compassion. In church we can learn how to assemble and fit them together. But the actual making of and fitting on of the shield of faith belongs in the family circle. (p. 8) [37]

As Latter-day Saints, we should not need scientific studies to validate the teachings of the scriptures or the counsel of living prophets. However, the results of our large study of LDS youth provide a powerful second witness. Religiosity—personal and family—connects like a ligament the various aspects of the lives of Latter-day Saint youth. The results clearly show that LDS adolescents who internalize gospel teachings are less involved in delinquent behaviors, do better in school, and feel a stronger sense of self-worth. Religion matters in the lives of LDS young people. Likewise, parents matter, and so does the “house of faith” they provide for their children.

References

Notes

[1] Smith, C., & Denton, M. L. (2005). Soul searching: The religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press.

[2] Stark, R. (1984). Religion and conformity: Reaffirming a sociology of religion. Sociological Analysis, 45(4), 273–282.

[3] Hirschi, T., & Stark, R. (1969). Hellfire and delinquency. Social Problems, 17 (2), 202–213.

[4] Smith, C., & Denton, M. L. (2005). Soul searching: The religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press.

[5] Dean, K. C. (2010). Almost Christian: What the faith of our teenagers is telling the American church. New York: Oxford University Press.

[6] Dean, K. C. (2010). Almost Christian: What the faith of our teenagers is telling the American church. New York: Oxford University Press.

[7] Chadwick, B. A., Top, B. L., & McClendon, R. J. (2010). Shield of faith: The power of religion in the lives of LDS youth and young adults. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

[8] Top, B. L., Chadwick, B. A., & Garrett, J. (1999). Family, religion, and delinquency among LDS youth. Religion, Mental Health and the Latter-day Saints. D. K. Judd (Ed.). Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 129–168.

[9] Chadwick, B. A., & Top, B. L. (1993). Religiosity and delinquency among LDS adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 32(1), 51–67.

[10] Smith, C., & Denton, M. L. (2005). Soul searching: The religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press.

[11] Chadwick, B. A., Top, B. L., & McClendon, R. J. (2010). Shield of faith: The power of religion in the lives of LDS youth and young adults. Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

[12] Top, B. L., & Chadwick, B. A. (2006, February). Helping children develop feelings of self-worth. Ensign, 36(2), 32–37.

[13] Top, B. L., & Chadwick, B. A. (2004). 10 secrets wise parents know. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book.

[14] Top, B. L., Chadwick, B. A., & McClendon, R. J. (2003). Spirituality and self-worth: The role of religion in shaping teens’ self-image. Religious Educator, 4(2), 77–93.

[15] Top, B. L., & Chadwick, B. A. (1999, March). Helping teens stay strong. Ensign, 29(3), 27–34.

[16] Top, B. L., & Chadwick, B. A. (1998). Rearing righteous youth of Zion: Great news, good news, not-so-good news. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft.

[17] Top, B. L., & Chadwick, B. A. (1993). The power of the word: Religion, family, friends, and delinquent behavior of LDS youth. BYU Studies, 33(2), 41–67.

[18] Harris, J. R. (2009). The nurture assumption: Why children turn out the way they do. New York: Simon & Schuster.

[19] Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1992). Pygmalion in the classroom: Teacher expectations and pupils’ intellectual development. Norwalk, CT: Irvington Publishers; Sheffield, South Yorkshire: Ardent Media.

[20] Rosenthal, R. (1973). The Pygmalion effect lives. Psychology Today, 7(4), 56–63

[21] Hansford, B. C., & Hattie, J. A. (1982). The relationship between self and achievement/

[22] Pipher, M. (1994). Reviving Ophelia: Saving the selves of adolescent girls. New York: Ballantine Books.

[23] Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Kreuger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(1), 1–44.

[24] Stark, R. (1984). Religion and conformity: Reaffirming a sociology of religion. Sociological Analysis, 45(4), 273–282.

[25] Faust, J. E. (1990). The greatest challenge in the world—good parenting. Official Report of the 160th Semiannual General Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

[26] Ballard, M. R. (1996, May). Feasting at the Lord’s table. Ensign, 26(5), 81.

[27] First Presidency and Council of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (1995, November). The family: A proclamation to the world. Ensign, 25(11), 102.

[28] Eyring, H. B. (1996, May). A legacy of testimony. Ensign 26(5), 63.

[29] First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (1999, June). Keeping children close to the Church. Ensign, 29(6), 80.

[30] First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (1999, June). Keeping children close to the Church. Ensign, 29(6), 80.

[31] First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (1915, June). Home evening. Improvement Era, 18(8), 733–734.

[32] First Presidency of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (1915, June). Home evening. Improvement Era, 18(8), 733–734.

[33] Benson, E. T. (1977, November). A message to the rising generation. Ensign,7 (11), 3032.

[34] Benson, E. T. (1988). The teachings of Ezra Taft Benson. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft.

[35] Hinckley, G. B. (1997). Teachings of Gordon B. Hinckley. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book.

[36] Whitney, O. F. (1967). Life of Heber C. Kimball (3rd ed.). Salt Lake City: Bookcraft.

[37] Packer, B. K. (1995, May). The shield of faith. Ensign, 25(5), 8.