"With Full Authority to Build Up the Kingdom of God on Earth"

Lyman Wight on the Council of Fifty

Christopher James Blythe

Christopher James Blythe, “With Full Authority to Build Up the Kingdom of God on Earth,” in The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History, ed. Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 141-152.

Christopher James Blythe is a historian with the Joseph Smith Papers Project. His published work has appeared in journals such as Journal of Mormon History, BYU Studies Quarterly, Nova Religio, and Material Religion.

Members of the Council of Fifty—or the kingdom of God, as it was also often called—took various positions in the succession crisis after Joseph Smith’s death. The majority of council members accepted the succession claim of Brigham Young and the Twelve Apostles and in turn supported Young in 1845 as the “prophet, priest, and king” of the council.[1] On the other hand, some council members believed they had been granted special responsibilities as part of the Fifty that they could now fulfill independently of the Church’s hierarchy. Others insisted that the council itself should become the governing voice of the Church.

Both Lyman Wight and Young agreed that the best course of action was to pursue the plans that Joseph Smith had revealed and prioritized before he died. Yet their zeal led these men to take starkly different roads in fulfilling these ends. This chapter examines the place of Wight in the history of the Council of Fifty, demonstrating how a man who attended only three council meetings became the council’s most outspoken public advocate in the late 1840s and early 1850s. As the leader of a small colony in Texas, he spent his last years trying to live up to what he believed were his and the council’s most important commissions—even when it came to him opposing his fellow members of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles.

Texas

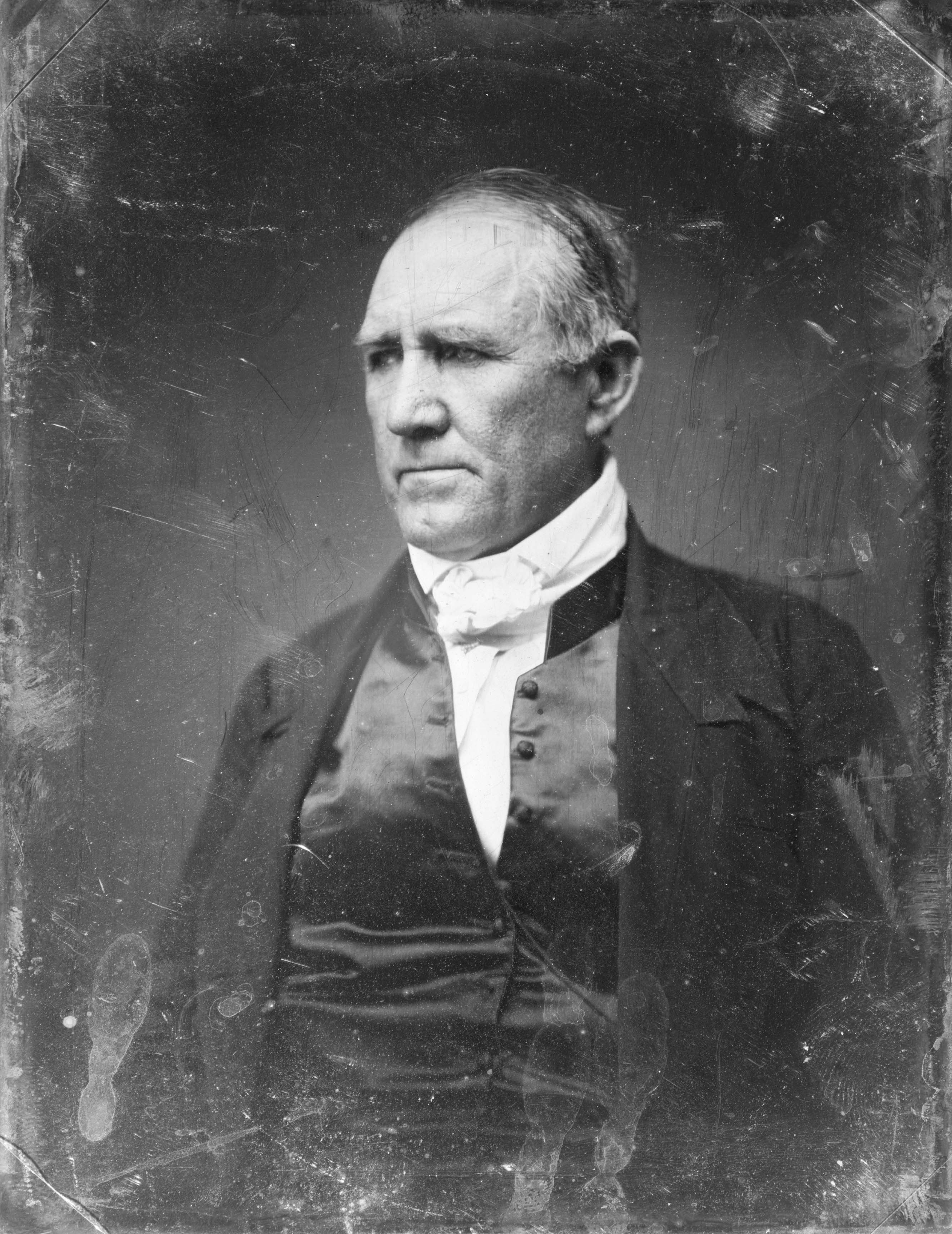

Council member Lucien Woodworth traveled to the Republic of Texas in spring 1844 to negotiate with Texas president Sam Houston for a possible Mormon settlement in the republic. Daguerreotype of Houston, circa 1848 to 1850, by Mathew B. Brady studio. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Council member Lucien Woodworth traveled to the Republic of Texas in spring 1844 to negotiate with Texas president Sam Houston for a possible Mormon settlement in the republic. Daguerreotype of Houston, circa 1848 to 1850, by Mathew B. Brady studio. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Although Wight did not attend a meeting of the Council of Fifty until May 1844, his proposal for a Latter-day Saint settlement in the Republic of Texas was a major impetus for the council’s preliminary meeting on March 10. Beginning in 1841, apostle Lyman Wight and bishop George Miller had been assigned to lead a colony in charge of gathering lumber in an area known as the “Pineries” in Wisconsin Territory.[2] In February 1844, Wight and other representatives from the colony wrote to Nauvoo, presenting various reasons to establish a settlement in Texas. When Joseph Smith received the letters, he appointed a committee to meet and discuss the proposal. According to Smith’s journal, the committee determined to “grant their petition,” including giving the “go ahead concer[n]ing the indians. & southern states &c.” Apparently, the committee also discussed the possibility of sending men from the Pinery to Santa Fe to meet with Sam Houston and see if he “will embrace the gospel.”[3]

Establishing a settlement in the Republic of Texas remained a central item on the Council of Fifty’s 1844 agenda. On March 14, 1844, the council dispatched an emissary, Lucien Woodworth, to visit Sam Houston and discuss the possibility of a settlement.[4] Some retrospective accounts of council members went so far as to suggest that Texas was given priority in the council’s discussions about colonization. For instance, George Miller recalled that the council’s primary goal was “to have Joseph elected President,” that thereby “the dominion of the kingdom would be forever established in the United States. And if not successful, we could but fall back on Texas, and be a kingdom notwithstanding.”[5] Yet the minutes of the meetings of the Fifty reveal that Texas was only one of multiple locations considered.

On April 18, 1844, Joseph Smith even expressed his hope that Nauvoo could be recognized as an “independant government,” rendering it unnecessary for the majority of the Saints to leave the region. He admitted, “I have no disposition to go to Texas, but here is Lyman Wight who wants to go.”[6] Wight was not present for that meeting or in the council’s organizational meeting when council members decided they would “look to some place where we can go and establish a Theocracy either in Texas or Oregon or somewhere in California.”[7] In fact, when Wight arrived in Nauvoo to be officially admitted into the council, the first meeting he attended on May 3 was dominated by discussion of Texas prompted by Woodworth’s return from meeting with Houston.[8] Joseph Smith and other council members deliberated on the possibility of a future Mormon presence in the Republic of Texas, including the Saints’ involvement in the struggling Texas government.

At the May 6 council meeting, Wight expressed his desire “to have those families now at the pinery go to Texas.” According to the minutes, Smith agreed and “suggested the propriety of those families going to the Texas and not telling who they are.” Presumably, Smith wanted to continue talks with Houston about Mormons arriving pursuant to an official agreement and thus did not want the members of the Black River Falls colony announcing their religious affiliation. Brigham Young followed Smith’s remarks and moved that Wight, like other apostles, should first “go through the United States electioneering for the Presidency.” Young later moved “that the brethren in the pine country be committed to the council of Ers [Elders] Wight, Woodworth and Miller.” The minutes note that the proposal was “carried unanimously.”[9]

This meeting held great significance for Wight throughout his life. However, when he wrote his own account of that day four years later, his version differed from the official minutes in that it emphasized Smith’s role in the decisions. Wight recalled that it was Smith who brought up the Texas mission and declared, “‘Let George Miller and Lyman Wight take the Black river company and their friends, and go to Texas, to the confines of Mexico, in the Cordilleras mountains; and at the same time let Brother Woodworth, who has just returned from Texas, go back to the seat of government in Texas, to intercede for a tract of country which we might have control over, that we might find a resting place for a little season.’ A unanimous voice was had for both Missions.” According to Wight, Smith also moved that Wight should go to the East to “‘hold me up as a candidate for President of the United States at the ensuing election; and when they return let them go forth with the Black river company to perform the Mission which has been voted this day.’ Which again called the unanimous voice of the Grand Council.” After the meeting, Wight met with Smith in “a private chamber” where the Prophet spoke further about the Texas mission and told him that if Congress rejected a proposal for the Saints to raise troops to defend Texas, “‘get 500,000 if you can and go into that country.’ He instructed me faithfully concerning the above Mission.”[10]

Wight’s Commission to Texas

Not surprisingly, when Wight returned to Nauvoo from his electioneering mission after Joseph Smith’s martyrdom, he was eager to begin this commission. On August 12, 1844, during a meeting of the Quorum of the Twelve, Wight expressed his desire to take the Black River Falls colony to Texas. The apostles, perhaps grudgingly, passed a resolution “that Lyman Wight go to Texas as he chooses, with his company, also George Miller and Lucien Woodworth, and carry out the instructions he has received from Joseph—to procure a location.”[11] This was far from a breaking point between Wight and Young, but it was the beginning of Wight’s estrangement from the Church.

Young warned Wight that he did not want others outside of the Black River Falls company accompanying him to Texas. His concern seems to have been that Wight would draw off resources—both human and material—from Nauvoo, which would render the construction of the temple and a future exodus, if necessary, much more difficult. He even cautioned Wight that he “would have to speak a little against [his] going for fear the whole Church to a man would turn out.”[12] Wight agreed to this condition. Likewise, when Heber C. Kimball urged the colony that had relocated to Nauvoo in July to first move to Wisconsin before making the trek to Texas, Wight complied.[13] In these early days after the martyrdom, Wight seems to have seen himself as completely loyal to his fellow apostles. He supported the Twelve’s taking the lead of the Church, which he viewed as a strategic move to withstand “aspiring men,” such as Sidney Rigdon and James Strang, who were seeking to be recognized as prophets over the Church.[14] On November 6, 1844, the colony in Wisconsin publicly sustained “the Twelve Apostles of this church in their state and standing and all other authorities with them.”[15]

Rupture with the Quorum of the Twelve

On the other hand, observable fractures in the relationship between Wight and the Twelve seemed evident during the October 1844 conference in Nauvoo. The minutes, as published in the Times and Seasons the following month, stated that Brigham Young referred to “Wight’s going away because he was a coward.”[16] While Young may have been simply fulfilling his promise to Wight that he would “speak a little against” the mission, Wight was greatly offended by the barb.[17] Sentiment toward Wight in Nauvoo was changing. Rumors were circulating that Wight was not actually as loyal to the Twelve as he pretended.[18] In February 1845, when Young revived the Council of Fifty, Wight with several others was expelled from the kingdom.[19] In April, the Twelve sent a messenger to Wight’s colony—who had already begun their trek to Texas—with a letter, counseling them to abandon their plans to go west until after they could receive their endowments in the temple.[20] Directly disobeying orders for what seems to have been the first time, Wight continued to lead his colony on their southwestern journey. The colony eventually settled near Austin in a village they named Zodiac.[21] During the October 1845 conference, Church leaders deliberated on whether he should remain a member of the Quorum of the Twelve.[22]

From Texas, Wight may have become increasingly aware of the Church’s diminishing opinion of him and the Texas mission from the Times and Seasons or occasional visitors, but it was the arrival of George Miller that set him off. Miller, who had remained in Nauvoo, joined the Texas colony in 1848 after his own falling out with Brigham Young. He likely brought word that Wight had been expelled from the Council of Fifty in February 1845, when Young had revived the kingdom.[23] It was shortly after Miller’s arrival that Wight, now incensed, decided to publicly defend his position and standing in the Church. The result was a sixteen-page pamphlet titled An Address by the Way of an Abridged Account and Journal of My Life from February 1844 up to April 1848, with an Appeal to the Latter-day Saints.

The first nine pages followed Wight’s life from his proposal for a Mormon colony in Texas to his eventual journey to Texas by way of Wisconsin, touching on his initiation into the Council of Fifty, electioneering mission, and return to Nauvoo. This is a noteworthy publication because of Wight’s candidness about the details of the Council of Fifty. Likely because members of the Fifty swore an oath of secrecy on admission to the council, there are no comparable public histories of the Fifty. Wight’s willingness to ignore this vow is unusual, but he may have believed this was his only means to defend his position. He characterized the Fifty as an ecclesiastical organization. It was the “Grand Council of the Church, or in other words, the perfect organization of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints on earth. This council consisted of fifty members, with full authority to build up the Kingdom of God on earth, that his will might be done on earth as in heaven.”[24] He also explained, as noted above, his specific assignment to begin a settlement in Texas.

In the second half of the pamphlet—what Wight termed his “appeal”—he defended his character and his place as one of the Twelve Apostles, and protested his removal from the Council of Fifty. He explicitly challenged “those of a like ordination unto myself that they have neither power nor authority given them, to move me from this station, nor to place any long eared Jack Ass to fill a place, which has never been vacated. . . . I have not forfeited my right, title nor claim to a seat with the Twelve, neither with the Grand Council of God on the earth.”[25] Finally, he invited “all ye inhabitants of the earth” to join him on his mission in Texas.[26]

Ultimately, the pamphlet was the point of no return for Wight’s relationship with the Church as continued under the authority of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles. He sent messengers to distribute the pamphlet to Latter-day Saint branches in Iowa and throughout the Midwest.[27] Just as Wight had prioritized his commission to establish a settlement in Texas over the apostles’ efforts to construct the temple in Nauvoo, his pamphlet clarified that he viewed other colonization efforts as inferior to his own. More important, what the pamphlet revealed was that the division between Brigham Young and Lyman Wight had less to do with their competing priorities than it did with their fundamental interpretations of the Council of Fifty. Young saw the Council of Fifty as an nonecclesiastical institution organized for deliberating on political concerns. He viewed the council as an important fulfillment of prophecy, but he also believed it was subservient to the needs of the Church and was rightfully under the direction of the Church’s leadership. Wight saw the Council of Fifty as the highest ecclesiastical institution of the Church. For Wight, the Twelve should report to the Fifty and not the other way around.

Differing Opinions on the Role of the Fifty

Wight was not the only council member to have held the belief that the Fifty was a new governing body over the Church. On April 18, 1844, the council devoted much of an afternoon meeting to resolving differing opinions on whether “the kingdom of God and the church of God are one and the same thing” or whether “the church is one thing and the kingdom another.” Joseph Smith concluded this discussion by explaining that “there is a distinction between the Church of God and kingdom of God. . . . The church is a spiritual matter and a spiritual kingdom; but the kingdom which Daniel saw was not a spiritual kingdom, but was designed to be got up for the safety and salvation of the saints by protecting them in their religious rights and worship.”[28] While this resolved the debate during Smith’s lifetime, only a month after the martyrdom, two members of the Council of Fifty wanted to “call together the Council of Fifty and organize the church.” Church leaders rebuffed the idea and explained “that the organization of the church belonged to the Priesthood alone.”[29] James Emmett, like Wight, also set out on a mission based on a commission he received from the Council of Fifty. His company spoke of the Council of Fifty as “the highest court on earth.”[30]

Yet, by 1848, there were few advocates for this interpretation that the Council of Fifty should govern the Church. Wight’s pamphlet seems to have revived this sentiment among at least some members of the council. Council members Lucien Woodworth and Peter Haws visited Zodiac, perhaps with intentions to stay.[31] As council member Alpheus Cutler started his own mission with connections to the Fifty, his followers likewise met with Wight.[32] In 1853, Cutler established a church with himself as the head, arguing that the original Church had gone into apostasy but that he possessed higher authority as a member of the kingdom. While we cannot be certain what degree Wight’s pamphlet influenced Cutler’s position that the kingdom was superior to the Church, it is an interesting coincidence that there would be a dialogue between these communities at that time.[33] Peter Haws, on the other hand, was inspired to defend Wight’s position to Church leaders in Iowa. After his return from Texas, Haws demanded Orson Hyde “call together the Council of Fifty, as there was important buisness to be attended to, and it was necessary that, that body should meet immediately as there was feelings, and important buisness to attend to.”[34] Memorably, he accused Brigham Young of failing “to carry out the measures of Joseph” by not fully utilizing the Council of Fifty, declaring “the Twelve had swallowed up thirty eight.”[35] That is, the Twelve had usurped the responsibility and authority that Smith had intended for the Fifty.

Conclusion

As Lyman Wight and his settlement in Texas had fewer interactions with other Latter-day Saint communities, the Council of Fifty still remained crucial to Zodiac’s identity. Local branch meetings even went so far as to publicly recognize “Lyman and George [Miller] in their standing as two of the Fifties.”[36] Wight continued to reflect on what the Fifty should have done after the martyrdom. In 1851, he wrote that “the fifties assembled should have called on all the authorities of the church down to the laymembers from all the face of the earth” and sustained the leadership of Joseph Smith III, who would have taken the lead of completing the temple. “Then,” Wight continued, “should the fifty have sallied forth unto all the world, and built up according to the pattern which Bro. Joseph had given; the Twelve to have acted in two capacities, one in opening the gospel in all the world, and organizing churches; and then what would have been still greater, to have counseled in the Grand Council of heaven, in gathering in the house of Israel and establishing Zion to be thrown down no more forever.”[37] In 1853, Wight still maintained his hope that “the majority of the fifty, which Br. Joseph organized, [would] assume their place and standing.”[38]

Notes

[1] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1, 1845, in Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 256 (hereafter JSP, CFM).

[2] See Matthew J. Grow and Brian Whitney, “The Pinery Saints: Mormon Communalism at Black River Falls, Wisconsin,” Communal Societies 36, no. 2 (2016): 153–70.

[3] Joseph Smith, Journal, March 10, 1844, in Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Brent M. Rogers, eds., Journals, Volume 3: May 1843–June 1844, vol. 3 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2015), 201 (hereafter JSP, J3).

[4] Joseph Smith, Journal, March 14, 1844, in JSP, J3:204.

[5] George Miller, Letter to “Dear Brother,” June 28, 1855, Northern Islander, September 6, 1855.

[6] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM: 127–28.

[7] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:40.

[8] Council of Fifty, Minutes, May 3, 1844, in JSP, CFM:137–47.

[9] Council of Fifty, Minutes, May 6, 1844, in JSP, CFM:157–58.

[10] Lyman Wight, An Address by the Way of an Abridged Account and Journal of My Life from February 1844 up to April 1848, with an Appeal to the Latter-day Saints (1848), 3–4. The actual petition was not limited to Texas, but included Oregon as well. See Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 26, 1844, in JSP, CFM:67–70.

[11] Willard Richards, Journal, August 12, 1844, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[12] Lyman Wight, Letter to Brigham Young, March 2, 1857, Church History Library.

[13] Heber C. Kimball, Journal, August 23, 1844, in Stanley B. Kimball, ed., On the Potter’s Wheel: The Diaries of Heber C. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1987), 82.

[14] Wight, Letter to “Dear Brother and Sister,” November 29, 1844, in Wight, An Address, 5.

[15] Crawford County Branch (Wisconsin), Minutes, November 6, 1844, Church History Library.

[16] “Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons, November 1, 1844, 5:694.

[17] Lyman Wight to Brigham Young, March 2, 1857, Church History Library.

[18] William Clayton, Journal, September 25, 1844, in George D. Smith, ed., An Intimate Chronicle: The Journals of William Clayton (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1991), 545.

[19] Council of Fifty, Minutes, February 4, 1845, in JSP, CFM:226.

[20] See Quorum of Twelve to Lyman Wight “and all the brethren with him,” April 17, 1845, Brigham Young Collection, Church History Library.

[21] See Melvin C. Johnson, Polygamy on the Pedernales: Lyman Wight’s Mormon Villages in Antebellum Texas, 1845 to 1858 (Logan: Utah State University, 2006), chaps. 3–4.

[22] “Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons, November 1, 1845, 6:1009.

[23] Council of Fifty, Minutes, February 4, 1845, in JSP, CFM:226.

[24] Wight, An Address, 3.

[25] Wight, An Address, 12.

[26] Wight, An Address, 16.

[27] Lucius Scovil to Samuel Brannan, December 17, 1848, Church History Library.

[28] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:121, 128.

[29] History, 1838–1856, vol. F-1, Addenda, 9, Church History Library.

[30] William D. Kartchner, Reminiscences and Diary, 19, Church History Library. For a discussion of Emmett’s mission, see Jeffrey D. Mahas, “‘The Lamanites Will Be Our Friends’: Mormon Eschatology and the Development of a Mormon-Indian Racial Identity in the Council of Fifty,” unpublished.

[31] Lucius Scovill to Samuel Brannan, December 17, 1848, Church History Library.

[32] See Danny Jorgensen, “Conflict in the Camps of Israel: The 1853 Cutlerite Schism,” Journal of Mormon History 21 (Spring 1995): 41–42.

[33] For Cutler’s understanding of the Council of Fifty, see Christopher James Blythe, “The Church and the Kingdom of God: Ecclesiastical Interpretations of the Council of Fifty,” Journal of Mormon History 43, no. 2 (2017): 113–16.

[34] Orson Hyde, George A. Smith, and Ezra T. Benson, Report to “Presidents Brigham Young, Heber C Kimball, Willard Richards, and the Authorities of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in Zion,” April 5, 1849, Church History Library.

[35] Hyde et al., Report, April 5, 1849.

[36] William Leyland, Sketches on the Life and Travels of William Leyland, Community of Christ Library and Archives, Independence, Missouri, 20.

[37] This document was quoted in The History of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Independence, MO: Herald House, 1896), 2:791. The original was destroyed in the Herald Publishing House fire in 1907.

[38] Lyman Wight, Letter to Benjamin Wight, January 1853, Community of Christ Library and Archives.