Carma T. Prete, “Canada's North: The Last Frontier,” in Canadian Mormons: History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Canada, ed. Roy A. and Carma T. Prete (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 486-497.

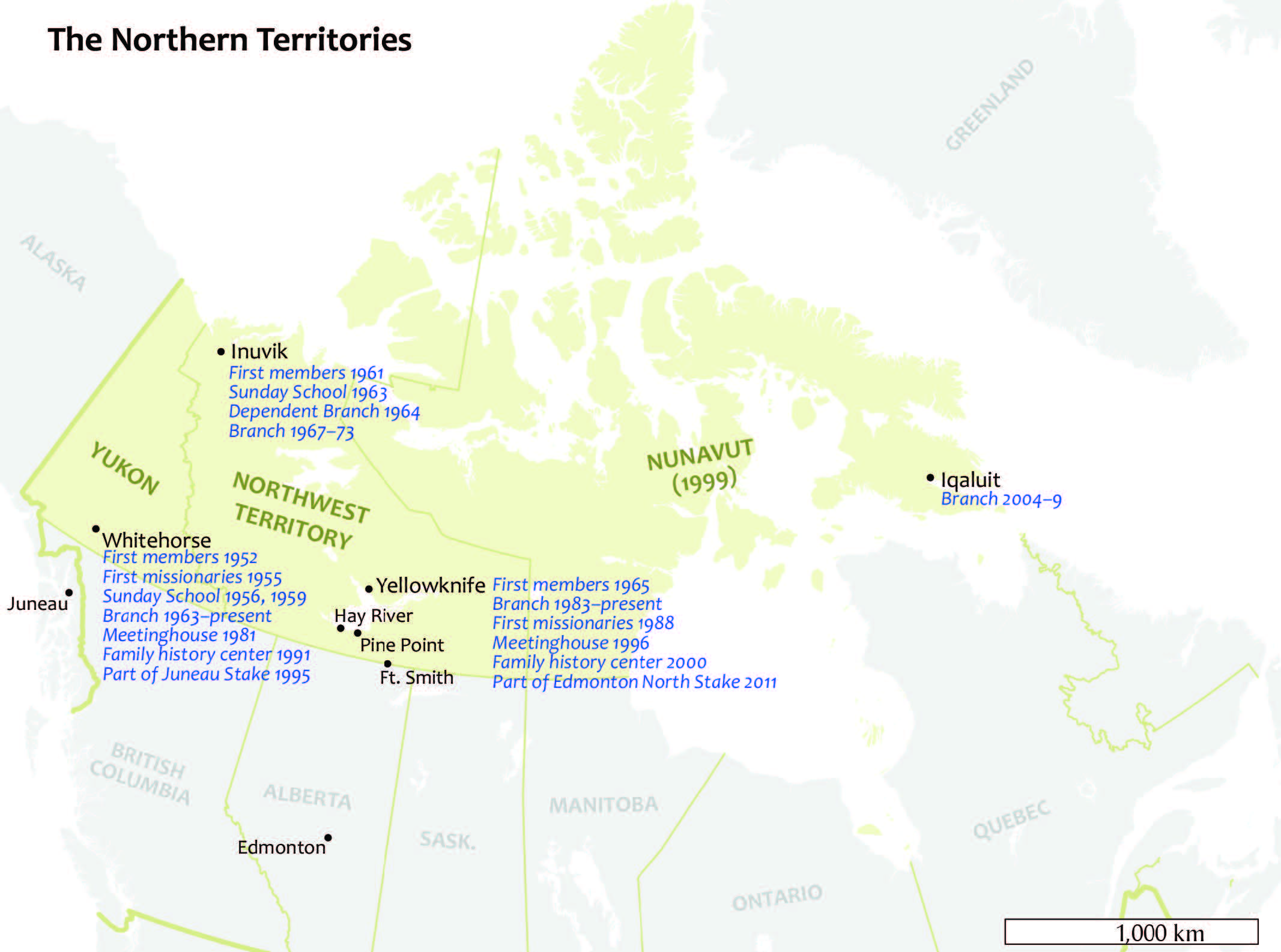

In the vast northern territories of Canada, sometimes considered the “Last Frontier,” unique challenges have confronted Church members, including immense distances, isolation, and a transient population. A few small branches or Sunday Schools were established in various locations and functioned for a time but had to close when Church members moved away. Permanent branches with meetinghouses have been organized in two larger cities—Whitehorse, capital of Yukon; and Yellowknife, capital of Northwest Territories.

In the vast northern territories of Canada, sometimes considered the “Last Frontier,” unique challenges have confronted Church members, including immense distances, isolation, and a transient population. A few small branches or Sunday Schools were established in various locations and functioned for a time but had to close when Church members moved away. Permanent branches with meetinghouses have been organized in two larger cities—Whitehorse, capital of Yukon; and Yellowknife, capital of Northwest Territories.

The three territories of Canada’s North—Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut—encompass an incomprehensibly large area, nearly 40 percent of Canada, with a total population in 2011 of less than 110,000, of whom more than 56,000 were Aboriginal peoples.[1] The combined territories span the area between Alaska on the west to Greenland on the east, from the Canadian provinces on the south to the North Pole. Nunavut, the largest of the three territories, did not come into existence until 1999, when the Northwest Territories was divided.[2] The Canadian north is a land of northern lights, ice roads, and permafrost. In Inuvik, Northwest Territories, located above the Arctic Circle, there are seven weeks of “midnight sun” in summer and thirty consecutive days in winter when the sun does not come up at all.[3]

In Canada’s far north, distances are immense and roads are few. Many settlements can be reached only by air, often by small bush planes. The territorial capitals—Whitehorse, Yukon; Yellowknife, Northwest Territories; and Iqaluit, Nunavut—are the largest cities in the Canadian North, though the largest of the three, Whitehorse, had a population of only 23,276 in 2011.[4] Since the economies of the northern territories are based largely on mining and other natural resource development, employment is particularly subject to the ups and downs of world markets. This, combined with the often short-term nature of government and service employment, results in a transient population.

Being a member of the Church in this beautiful, vast, remote, and unique area poses some distinct challenges, as illustrated in the following examples. On 11 February 1968, nineteen people attended the sacrament meeting of the Inuvik Branch, even though the outside temperature was –62° F. Inuvik Branch leaders did make one concession to the extreme temperatures: they cancelled the fireside scheduled for that evening “due to cold weather.”[5] In November 2012, five teenagers from the Yellowknife Branch, Northwest Territories, on the northern shores of Great Slave Lake, flew to Edmonton, nearly 1,000 kilometres (over 600 miles) away, to attend their stake youth conference.[6] In 2013, one family in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, regularly attended the sacrament meeting of the Yellowknife Branch, 853 kilometres (530 miles) away via Skype.[7]

Bush planes such as this are vital to transportation in Canada’s far North. Because of the vast distances, rugged terrain, and scarcity of roads, many settlements can only be reached by air. Planes are sometimes equipped with floats for landing on lakes and rivers, or with skis for landing on snow or frozen lakes. This photograph was taken in Whitehorse, where a Church member, Norman Drayton, was preparing to fly to Tuktoyaktuk, 977 kilometres to the north. (Carol Drayton)

Bush planes such as this are vital to transportation in Canada’s far North. Because of the vast distances, rugged terrain, and scarcity of roads, many settlements can only be reached by air. Planes are sometimes equipped with floats for landing on lakes and rivers, or with skis for landing on snow or frozen lakes. This photograph was taken in Whitehorse, where a Church member, Norman Drayton, was preparing to fly to Tuktoyaktuk, 977 kilometres to the north. (Carol Drayton)

In spite of the challenges of climate, distance and isolation, and a fluctuating economy, the Church has become established in the Canadian North, where in 2015 there was one branch in Whitehorse, Yukon, and another in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories. Two other branches—in Inuvik, Northwest Territories, and Iqaluit, Nunavut—functioned for about five years before being discontinued. Other families have lived in scattered locations away from organized branches of the Church. The story of the establishment and growth of the Church in the Canadian North is both interesting and inspiring.

Yukon

Yukon Territory, located directly east of Alaska and north of British Columbia, is a region larger than California, with spectacular scenery; rugged, snowcapped mountains; glaciers; powerful rivers; and volcanos (some active). Mining, petroleum, and forestry are principal industries, although hydroelectric projects, tourism, and government administration are also important factors in the economy. Of the 36,000 residents in the territory in 2012, more than three-quarters of them lived in the provincial capital, Whitehorse.[8]

In 1947, the Yukon and Northwest Territories were assigned to the Western Canadian Mission, but no record had been found of a Church presence in Canada’s far north until the early 1950s.[9] Norman Drayton and his family moved from Australia to Yukon in 1952, where Drayton was employed as a telephone engineer for Canadian National Telecommunications.[10] The first known missionaries in the far north came to Whitehorse in August 1955, where they stayed for three months and reported visiting Church members there.[11] On 12 August 1956, eleven people attended a meeting in Whitehorse, where a home Sunday School was organized, with Robert Lee North as presiding elder and Sunday School superintendent. It is not known how long this Sunday School operated, but it was reestablished in January 1959 with Norman J. Drayton as superintendent, Robert McDonald as counselor, and Noreen McDonald as secretary.[12] In May 1959, the first Relief Society meeting was held, and in June, the first convert was baptized.[13] Two missionaries were serving in Whitehorse in 1960.[14]

In November 1960, British Columbia and Yukon were separated from the Western Canadian Mission and combined with Alaska to form the Alaskan-Canadian Mission, with headquarters in Vancouver, nearly 1,500 kilometres (over 900 miles) from Whitehorse.[15] Three years later, on 15 October 1963, the Whitehorse Branch was organized as an independent branch, with Norman J. Drayton as president. Other branch leaders were also appointed that day, including Julian Symchych, counselor in the branch presidency; Liola Symchych, Relief Society president, with counselors Bertha Drayton and Rosalie Jo Bailey; and Julian Symchych, Sunday School superintendent, with Terrance Bailey as counselor. The branch held meetings in the Whitehorse Vocational School.[16] In March 1964, when Stewart A. Durrant, president of the Alaskan-Canadian Mission, attended branch conference at the Symchych home in Whitehorse, there were Thirty-five in attendance—100 percent of the Church members in Whitehorse.[17]

Norman Drayton, who arrived with his family in Yukon in 1952, became the first president of the Whitehorse Branch in 1963. Son John is standing in front of Beth and Norman Drayton; June Baker is standing on the right.

Norman Drayton, who arrived with his family in Yukon in 1952, became the first president of the Whitehorse Branch in 1963. Son John is standing in front of Beth and Norman Drayton; June Baker is standing on the right.

The Whitehorse Branch had begun holding meetings in the old Masonic hall by August 1965. This building had a temperamental oil heater that exploded from time to time, covering chairs and tables with a layer of black soot. It was necessary for Church members to arrive early every week to clean away the soot before they could hold meetings.[18] In November 1967, the Whitehorse Branch began holding meetings in the “new” Masonic hall, a substantial improvement over the former facilities. The branch held Sunday meetings and Wednesday night MIA activities in the new hall, but weekday Primary and Relief Society meetings continued to be held in the homes of Church members. Peter McCracken built a pulpit with wheels which could be rolled into position for sacrament meetings.[19]

Photo was taken in mid-1950s. L to R: John Drayton, Teddy Mostow, Beth Drayton. (Carol Drayton)

Photo was taken in mid-1950s. L to R: John Drayton, Teddy Mostow, Beth Drayton. (Carol Drayton)

This was a time of expanded activities for the Whitehorse Branch. Four young women attended district Young Women camp in Juneau, Alaska, in 1967. The Relief Society held a successful bazaar in November. By January 1968, the seminary program was operating.[21] The town of Whitehorse held its annual winter carnival, known as “Sourdough Rendezvous,” in February 1968. Members of the branch made a significant effort to support the community event, decorating the Queen’s Float for the parade and selling tickets at talent shows and dances. In March, the branch received a check for three hundred dollars from the carnival manager in appreciation for their support. The money was immediately earmarked for the Whitehorse Branch building fund.[22]

LeGrand Richards of the Quorum of the Twelve, on a tour of the Alaskan-Canadian Mission, arrived in Whitehorse on 24 July 1968, accompanied by the mission president, Arza A. Hinckley. Branch members offered their guests true Northern hospitality, serving them delicious meals and showing them the sights. At the branch conference held that evening, which lasted about three hours, branch members shed tears of joy to have an Apostle in their midst. The following day, Richards and Hinckley accompanied branch members to Takhini Hot Springs, eighteen miles from Whitehorse, to attend the baptism of four new converts. Branch members accompanied their guests en masse to the airport to bid them farewell.[23]

In 1970, Robert W. Miller was appointed president of the Whitehorse Branch, replacing Norman J. Drayton, who had served for seven years.[24] Other branch presidents followed during the next decade, including Vaun J. Stonehocker, Norman LeCheminant, Ernest Boyer, and Peter G. McCracken.[25] When the Alaska Anchorage Mission was created in 1974, Yukon became part of that mission.

The Whitehorse Meetinghouse

The Whitehorse Branch meetinghouse, completed in 1981. Its wood construction was uniquely adapted to the Yukon climate.[29] (Daniel Johnson)

The Whitehorse Branch meetinghouse, completed in 1981. Its wood construction was uniquely adapted to the Yukon climate.[29] (Daniel Johnson)

Although the Whitehorse Branch members had been raising money for their own building for some time, the prospects of having an LDS meetinghouse in Whitehorse in the foreseeable future were slim. When Douglas T. Snarr arrived in Anchorage in July 1978 as president of the Alaska Anchorage Mission, he recognized that meetinghouses were the key to the progress of the Church in Whitehorse and in other places in his mission and that innovative solutions were required. After study and investigation, Snarr proposed that precut, prefabricated buildings made of planed, tongue-in-groove cedar logs and designed to be suitable for the heavy snows and cold temperatures of the far northern climate, be constructed in selected locations in the mission, including Whitehorse. These buildings had an additional advantage: local members could provide a considerable amount of the labour on the building, thus fulfilling their requirement for local financial contribution.[26]

By September 1980, the land had been purchased and building materials had been delivered. Construction proceeded rapidly, aided by the labour of Church members and missionaries, some of whom had been assigned temporarily to Whitehorse especially for this task. The first meeting in the new building was held on 11 January 1981. In April 1981, the Whitehorse Branch gathered in their new building to watch a recording of general conference, the first general conference ever viewed in Whitehorse.[27] The new meetinghouse included a multipurpose room, classrooms, offices, and a baptismal font.[28] The construction of a Latter-day Saint meetinghouse signified the permanent establishment of the Church in Whitehorse.

The Whitehorse meetinghouse was dedicated on 8 February 1987 by Wilford Everett Thatcher, president of the Alaska Anchorage Mission.[30] The Whitehorse Yukon Family History Centre was opened in the meetinghouse in 1991.[31] A second phase was added to the building prior to 2004.[32] Branch presidents in Whitehorse since 1984 include Larry J. Baran, Gordon McDonald, Harry Hrebien, Robert G. Grant, Robert Richards, Jerry Johnson, Kenneth Sidney Tanner, Colin James Dean, Brian Little, and John M. Peterson.[33]

Having a local meetinghouse, nonetheless, did not resolve the problem of the distances between the branch and the stake centre or the temple. As related in a 2013 report, going to stake conference is a major undertaking for members of the Whitehorse Branch. Church members drive for two hours from Whitehorse to Skagway, Alaska, where they board a ferry for a seven-hour ride to Juneau, Alaska, the headquarters of their stake. Attending the temple requires even more time. Driving from Whitehorse to the Anchorage Alaska Temple takes thirteen hours with ideal road conditions, but can take up to twenty hours in winter.[34]

Colin and Margaret Dean are prime examples of the faith and dedication of Church members in coping with immense distances. After they moved to Faro, Yukon, in 1996, they regularly attended Sunday meetings in the Whitehorse Branch, 362 kilometres (225 miles) away, every week, year-round, even though the trip took up to five hours each way. They also regularly attended the distant Anchorage Alaska Temple after its dedication in 1999.[35]

Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories of Canada, bordering Yukon on the west; Nunavut on the east; and the provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan on the south, is a sparsely populated area of over 1.2 million square kilometres (nearly 750,000 miles). Gold, uranium, lead, zinc, tungsten, diamonds, oil, and natural gas have been found amid the rocks, forests, and lakes of the territory. The economy fluctuates as mines open and close, and, as a result, people move in and out of the Northwest Territories. The service industry, which tends to attract short-term employees, is also a major factor in the economy, contributing to the transience of the population, which has been a major challenge to the establishment of the Church.[36]

Inuvik

Between 1956 and 1962, the town of Inuvik was constructed by the Canadian government to be the northern headquarters for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Northern Affairs, the Canadian military, and various other government agencies. The town, located on the Mackenzie River delta 200 kilometres (about 125 miles) north of the Arctic Circle, was designed and built to meet the needs of government and military employees and a supporting civilian population living there in extreme Arctic conditions.[37] During the following years, Inuvik experienced significant ups and downs, with an oil and gas exploration boom in the 1970s and 1980s, its collapse in 1990, and the closure of the Canadian Forces Station in 1986. In 1990, the population peaked at 4,200, but in 2011 it still had 3,450 residents and remained an administrative centre for the western Arctic.[38]

Abiah J. Clark, shown here with his wife, Ora. He and his family moved to Inuvik in 1961, where he was the president of the Inuvik Branch from 1964 until about 1972. (Brent Clark)

Abiah J. Clark, shown here with his wife, Ora. He and his family moved to Inuvik in 1961, where he was the president of the Inuvik Branch from 1964 until about 1972. (Brent Clark)

A number of people moved to Inuvik in the early 1960s to accept employment there, including some Church members. Abiah J. Clark, for example, secured a position as superintendent for the Northern Canada Power Commission, with responsibility for power installations in Inuvik, Yellowknife, Fort Smith, and several other Northern communities, and he and his family moved to Inuvik in 1961.[39] Other Latter-day Saints followed, including the Allred, Hatch, and Bowden families.[40] In May 1963, a dependent Sunday School was formed.[41] In March 1964, a dependent branch was formed in Inuvik, with Abiah Clark as branch president.[42] Carroll Smith, president of the Western Canadian Mission, flew to Inuvik to create the dependent branch. He spent four days in Inuvik and described the morale of the Church members there as “very high.”[43] It was reported that Smith and his wife had a delightful time riding around in a dog sled.[44]

By 1965, the branch was meeting in the Sir Alexander Mackenzie School. They held youth firesides, teacher training classes, and a genealogy course in addition to regular Sunday and auxiliary meetings. Home teaching was organized that year, and by 1966 seminary was operating in Inuvik.[45] Total branch membership in December 1966 was fifty.[46] On 4 June 1967, Inuvik was organized as an independent branch, and Abiah Clark remained branch president. J. Talmage Jones, the mission president who presided at the creation of the new branch, believed that the Inuvik Branch was the northernmost branch of the Church in the world.[47]

The Inuvik Branch Relief Society, mid-1960s. Back row, left to right: Mariam Allred (second counselor), Ora Clark (president), Velma Hatch (first counselor), Eloise Tolley; front row, left to right: Henrietta Squires, Myrna Clark, Ann Dixon, Julie Trennert. This was the most northerly Relief Society in the world, at 68° north latitude. (Brent Clark)

The Inuvik Branch Relief Society, mid-1960s. Back row, left to right: Mariam Allred (second counselor), Ora Clark (president), Velma Hatch (first counselor), Eloise Tolley; front row, left to right: Henrietta Squires, Myrna Clark, Ann Dixon, Julie Trennert. This was the most northerly Relief Society in the world, at 68° north latitude. (Brent Clark)

Sunday School of the Inuvik Branch, 1960s. Note the young families, with children and teenagers, and the warm winter clothing. (Brent Clark)

Sunday School of the Inuvik Branch, 1960s. Note the young families, with children and teenagers, and the warm winter clothing. (Brent Clark)

In November 1968, four Latter-day Saint families moved from Inuvik, and although other new families continued to move in, move-outs were more common. The transience of the population due to a variable economy and the temporary nature of many employment positions proved to be a major challenge, as in many towns and cities in Canada’s far north. In early 1971, there were only three families in the branch—Abiah Clark, the branch president, and his wife, Ora; Reginald and Judy Keith and their children; and the Douglas and Eva Sayers family.[48] In June 1973, the branch was formally discontinued because the last remaining family—Douglas Sayers, branch president, and Eva Sayers, Relief Society president—moved away.[49]

There was, however, a temporary revival of a Mormon presence in Inuvik in 1980, with the move-in of a new family. But finding other scattered members and providing even the rudiments of a Church program under these conditions could be problematic.

Scattered Members

The issue of attending to the spiritual needs of isolated members weighed heavily on the mind of Bryan Espenscheid, president of the Western Canadian Mission. In June 1969, he created the Alberta Branch, which encompassed all Church members living in the mission who were outside the boundaries of existing wards and branches in northern Alberta and the Northwest Territories. Espenscheid appointed Octave Ursenbach, a seasoned Church leader, as president of the branch, which included approximately eight hundred members scattered throughout the Northwest Territories, northern Alberta, northern Saskatchewan, and northeastern British Columbia. Ursenbach and his wife, Jessie, were given the responsibility to write letters and generally keep in touch with these scattered members.[51] The Alberta Branch supervised Church members in the north until about 1979.[52]

The Yellowknife Branch

Meanwhile, there were a few Church members who had moved to Yellowknife, including the Frank Shields family and Robert and Nadia Campbell. In June 1965, J. Talmage Jones, president of the Western Canadian Mission, encouraged Shields to form a Sunday School and Relief Society in the near future.[53]

Charles R. McCurdy was the presiding elder in Yellowknife until he moved away and was replaced by Doran W. Flexhaug in September 1973. At that time, there were twenty-six Church members in Yellowknife who gathered together regularly for Sunday School, sacrament meeting, priesthood meeting, and Relief Society. It was also reported that at that time there were three or four Latter-day Saint families living in Hay River and two families in Pine Point.[54]

Gordon and Sylvia Haslam and their seven children lived in Fort Smith from the 1970s until 1989. Although the family technically lived within the boundaries of the Yellowknife Branch, Yellowknife was nearly nine hours’ drive away, so the family held meetings in their own home. Occasionally they would travel to Hay River, nearly four hours away, to meet with other Church members who were isolated from an organized unit of the Church.[55]

On 15 May 1983, the Yellowknife Branch was created. It was, at that time, a part of the Northwest Territories District of the Canada Calgary Mission.[58] By 1988, when the first known missionaries arrived, there were about a hundred people in the Yellowknife Branch, including fifty who lived in and near Yellowknife and another fifty who lived in scattered and distant communities.[59] The branch sent out regular monthly newsletters to keep Church members living far from Yellowknife informed of news and branch events. Occasionally, branch members would drive hundreds of kilometres on unpaved roads to gather together for social activities.[60] By May 1989, the branch was holding meetings in Northern United Place.[61]

In October 1988, Brian Randall was serving as president of the Yellowknife Branch.[62] Some of the other men who served as branch president in Yellowknife after that time include Eric Edwards, Roberto Jordão Batista Sousa, Raymond Jean Eugene Joseph Bilodeau, Bruce Coomber, Monte Ray Christensen, Lorne Bertram Sutherland, Thomas E. Garrett, Stephen E. Bellis, Japheth Trumpet, and Lawrence R. Heyn.[63]

Missionaries laboured in Yellowknife intermittently over the years, including senior couples. There were eight convert baptisms reported in Yellowknife during the first ten months of 1993.[64] The Yellowknife Branch meetinghouse was dedicated on 16 October 1996.[65]

The Yellowknife Branch meetinghouse, dedicated in 1996, included living accommodations for missionaries and, later, a family history centre. (Thomas and Juanita Garrett)

The Yellowknife Branch meetinghouse, dedicated in 1996, included living accommodations for missionaries and, later, a family history centre. (Thomas and Juanita Garrett)

In July 1998, the Northwest Territories became part of the newly created Canada Edmonton Mission.[66] Then the Yellowknife Northwest Territories Family History Centre opened in the Yellowknife meetinghouse in October 2000.[67] However, the closure of the two gold mines in the area in 2003 and 2004 was only partially compensated for by the development of diamond mines 200–300 kilometres northeast of Yellowknife. The loss of employment opportunities led to a decline in membership of the branch, as several families moved away.[68]

The Yellowknife Branch became part of the Edmonton Alberta North Stake in 2011.[69] The stake utilized available communications technology, such as webcasting and personal videoconferencing, to enable Church members in the Yellowknife Branch to more fully participate in stake meetings and conferences.[70] In November 2012, when the Edmonton Alberta North Stake held a youth conference five youth from the Yellowknife Branch attended. Because Yellowknife is nearly 1,000 kilometres (over 600 miles) from Edmonton, the Church paid for the youth to fly to and from the conference.[71]

Women in the Yellowknife Branch celebrating the Relief Society anniversary, March 2013. (Thomas and Juanita Garrett)

Women in the Yellowknife Branch celebrating the Relief Society anniversary, March 2013. (Thomas and Juanita Garrett)

Shirley Jean Monckton-Milnes, Relief Society president of the Yellowknife Branch in November 2012, dressed for her four-block walk home from church. (Thomas and Juanita Garrett)

Shirley Jean Monckton-Milnes, Relief Society president of the Yellowknife Branch in November 2012, dressed for her four-block walk home from church. (Thomas and Juanita Garrett)

Stephen Bellis, who served in branch presidencies from 2013 to 2016, dressed for winter weather. (Thomas and Juanita Garrett)

Stephen Bellis, who served in branch presidencies from 2013 to 2016, dressed for winter weather. (Thomas and Juanita Garrett)

Transportation in the far north in the larger cities is characterized by an abundance of pick-up trucks and SUVs. Dog teams have long since been replaced by snowmobiles for off-road travel but have remained a popular tourist attraction. Missionaries, recreating on a day off, are seen here in January 2016 on Grace Lake, Yellowknife, enjoying the challenges and exhilaration of dogsledding. (Larry Heyn)

Transportation in the far north in the larger cities is characterized by an abundance of pick-up trucks and SUVs. Dog teams have long since been replaced by snowmobiles for off-road travel but have remained a popular tourist attraction. Missionaries, recreating on a day off, are seen here in January 2016 on Grace Lake, Yellowknife, enjoying the challenges and exhilaration of dogsledding. (Larry Heyn)

Nunavut

On 1 April 1999, the Canadian Parliament divided the Northwest Territories to create a new territory called Nunavut. The division was made essentially on cultural and linguistic lines. More than 80 percent of the people in Nunavut are native Inuit, speaking the Inuktitut languages. Iqaluit, formerly known as Frobisher Bay, was designated the territorial capital.[74] Nunavut is the easternmost of the Canadian territories, extending from the Northwest Territories on the west to Greenland on the east, with over 2.25 million square kilometres (about 1.4 million miles). The territory’s population of 33,000 resides in twenty-eight small, spread-out communities. There are no roads connecting Nunavut with the rest of Canada. Transportation in and out of the territory is by boat or small plane. The economy is based on fishing, tourism, mining, and selling soapstone sculptures and other Inuit arts and crafts.[75]

After the creation of Nunavut, the territory was placed within the boundaries of the Canada Montreal Mission. In June 2004, Brian Higgins, an Iqaluit resident, was baptized while visiting Ottawa, Ontario, and in September, David O. Ulrich, president of the Canada Montreal Mission, sent two missionaries to Iqaluit to support the new convert and to begin missionary work there.[76] By the end of 2004, Ulrich reported that a small branch of about ten Church members had been created in Iqaluit, with a missionary serving as branch president.[77] Andy and Jolene Plunkett, Leona Aitken, and Evelyn Chemko were members of the branch.[78] Eventually, members replaced missionaries in leadership positions, and Iqaluit branch presidents included Jeffrey Dale Spackman, Donald J. Pratt, Darrel Paulus Larson, and Timothy P. Bradshaw.[79]

David O. Ulrich and his wife visited Iqaluit in 2005, and the next year, Alain André Jean-Baptiste Petion, the new president of the Canada Montreal Mission, also visited Iqaluit with his wife. In 2006, the mission boundaries were readjusted to include only the eastern part of Nunavut within the Canada Montreal Mission, with the western area of Nunavut becoming part of the Canada Edmonton Mission. This change was made because communities in Nunavut are accessible only by air, and existing air routes provided better access to western Nunavut from Edmonton than from Montreal.[80] Despite these efforts, the Iqaluit Branch was discontinued in 2009.[81]

Conclusions

In the Canadian far north, branches sometimes thrive and sometimes shrink because of economic fluctuations and the transience of the population. Branches which functioned for a time in smaller centres, such as in Inuvik (1967– 73) and Iqaluit (2004– 9), have succumbed to the periodic loss of members. Larger centres have fared better. With well-established branches in Whitehorse and Yellowknife, each with its own meetinghouse, there is a foundation for future growth. Church members in these northerly areas of Canada, nevertheless, continue to face the challenges of climate, distance, and the isolation of scattered members, although communications technology has somewhat ameliorated the limitations of distance and isolation. Faithful Saints of the future, with pioneer zeal, may be expected to rise to the challenges, as have those in the past.

Notes

[1] Statistics Canada, “Population and Dwelling Count Highlight Tables, 2011 Census,” last modified 13 January 2014, http://

[2] “Explore Nunavut,” http://

[3] Town of Inuvik, “Travel Information,” http://

[4] Statistics Canada, “Whitehorse, Yukon,” http://

[5] “Inuvik Branch General Minutes (hereafter IBGM),” 11 February 1968, folder 2, Church History Library, Salt Lake City (hereafter CHL), LR 16377 11.

[6] Thomas and Georgia [Juanita] Garrett, “Cold to Serve,” blog entry of 14 November 2012, http://

[7] “Edmonton Alberta North Stake Annual Historical Reports (hereafter EANSAHR),” 2013, CHL, LR 378089 3.

[8] Yukon Communities, “Whitehorse, Population and Labour Force,” Yukon Community Profiles, http://

[9] Deseret News 2013 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2013), 453.

[10] Carol Drayton, email to Carma Prete, 19 September 2015.

[11] Western Canadian Mission historical record, 20 August, 13 October 1955, Canada Calgary Mission Manuscript History and Historical Reports (hereafter WCM, CCMMHHR), box 1, volume 2, folder 1, CHL, LR 10539 2.

[12] WCM, CCMMHHR, Quarterly Historical Report, 30 September 1956, 31 March 1959, box 1, volume 2, folder 2, CHL, LR 10539 2.

[13] WCM, CCMMHHR, Quarterly Historical Report, 30 June 1959, box 1, volume 2, folder 2, CHL, LR 10539 2.

[14] Gail Johnson, email to Brian Sokolowsky, Church History Department, 18 June 2004, LDS Church History in Yukon Territory, CHL, MS 18789.

[15] Lethbridge Stake, A History of the Mormon Church in Canada (Lethbridge, Alberta: Corporation of the President, Lethbridge Stake, 1968), 285–86.

[16] Alaskan-Canadian Mission, Quarterly historical report, 31 December 1963, Canada Vancouver Mission Manuscript History and Historical Reports (hereafter ACM, CVMMHHR), box 1, folder 1, CHL, LR 10530 2. See also Lethbridge Stake, Mormon Church in Canada, 301, and R. J. Smith, “Recollections,” in Johnson, email to Sokolowsky, 29 June 2004, CHL, MS 18789.

[17] ACM, CVMMHHR, Quarterly Historical Report, 31 March 1964, box 1, folder 1, CHL, LR 10530 2. See also Lethbridge Stake, Mormon Church in Canada, 301.

[18] Lou Sutherland Hall and Beth Drayton, reminiscences, cited in Johnson, email to Sokolowsky, 29 June 2004, CHL, MS 18789.

[19] Quarterly Historical Report, 31 December 1967, Whitehorse Branch Manuscript History and Historical Reports (hereafter WBMHHR), CHL, LR 10146 2. See also Beth Drayton, “Recollections,” in Johnson, email to Sokolowsky, 29 June 2004, CHL, MS 18789; Whitehorse Branch General Minutes (hereafter WBGM), 12 and 19 November 1967, folder 2, CHL, LR 10146 11.

[20] Carol Drayton, email to Carma Prete, 14 January 2016; Theadore Michael Montour, KW8F-22T, www.familysearch.org.

[21] WBGM, 8 January 1967, 12 and 19 November 1967, 7 January 1968, folder 2, CHL, LR 10146 11. See also WBMHHR, 30 June and 30 September 1967, CHL, LR 10146 2.

[22] WBMHHR, 31 December 1968, CHL, LR 10146 2.

[23] ACM, CVMMHHR, Quarterly Historical Report, 30 September 1968, box 1, folder 2, CHL, LR 10530 2. See also Ronald G. Watt, “Northern Hospitality,” Church News, 8 July 1978, 16.

[24] WBMHHR, 31 December 1970, CHL, LR 10146 2.

[25] WBMHHR, Sustaining List, 17 December 1972, CHL, LR 10146 2; WBGM, 2 June 1974, folder 1, CHL, LR 10146 11; Historical Record, Section B—Historical Events, 1979, 1980, 1981, Alaska Anchorage Mission Annual Historical Reports (hereafter AAMAHR), box 1, folder 1, CHL, LR 14452 3.

[26] Historical Record, Section B—Historical Events, 1979, 1980, Alaska Anchorage Mission annual historical reports, box 1, folder 1, CHL, LR 14452 3.

[27] Letter, Bernell L. Christensen to Douglas T. Snarr, 21 April 1981, AAMAHR, box 1, folder 2, CHL, LR 14452 3.

[28] Historical Record, Section B—Historical Events, 1980, 1981, Alaska Anchorage Mission annual historical reports, box 1, folder 1, CHL, LR 14452 3. See also Johnson, email to Sokolowsky, 29 June 2004, CHL, MS 18789.

[29] Laurie Little, “Whitehorse, Yukon: A Way Up North,” 11 January 2013, Official website of LDS Church in Canada, https://

[30] Historical Record 1987, AAMAHR, box 1, folder 3, CHL, LR 14452 3.

[31] Whitehorse Yukon Family History Center general information, Church Directory of Organizations and Leaders (hereafter CDOL), last updated 9 January 2014, cdol.lds.org.

[32] Johnson, email to Sokolowsky, 29 June 2004, CHL, MS 18789.

[33] Whitehorse Branch historical information, CDOL, last updated 7 March 2014, cdol.lds.org.

[34] Little, “Whitehorse, Yukon: A Way Up North,” 11 January 2013.

[35] Johnson, email to Sokolowsky, 29 June 2004, CHL, MS 18789.

[36] “Northwest Territories,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/

[37] Inuvik, Canadian Forces Station, last updated 3 August 2010, http://

[38] “History of Inuvik,” Yukoninfo, www.yukoninfo.com/

[39] F. Brent Clark, son of Abiah Clark, email to Carma Prete, 27 August 2015.

[40] Brent Clark, email messages to Carma Prete, 27 August 2015.

[41] Lethbridge Stake, Mormon Church in Canada, 282.

[42] WCM, CCMMHHR, Quarterly Historical Report, 31 March 1964, box 2, volume 3, folder 2, CHL, LR 10539 2.

[43] WCM, CCMMHHR, box 2, vol. 3, folder 2, 31 March 1964, CHL, LR 10539 2.

[44] Clark, emails to Prete, 27 August 2015.

[45] IBGM, folder 1, 4 January, 20 June, and 9 September 1965, and 7 April 1966, CHL, LR 16377 11.

[46] Letter, J. Talmage Jones to Abiah J. Clark, 9 December 1966, Western Canadian Mission Mission President’s Files (hereafter WCMMPF), box 2, folder 2, CHL, LR 10539 25.

[47] CCMMHHR, Quarterly Historical Report, 30 June 1967, box 2, volume 4, folder 1, CHL, LR 10539 2. See also IBGM, folder 1, 4 June 1967, CHL, LR 16377 11.

[48] IBGM, folder 2, 3 November 1968, 2 May 1971, CHL, LR 16377 11.

[49] Historical Events of the Alberta-Saskatchewan Mission (hereafter ASM), 31 December 1973, CCMMHHR, box 2, volume 5, CHL, LR 10539 2.

[50] Jan Anderson, telephone conversation with Carma Prete, May 2015.

[51] WCM, CCMMHHR, Quarterly Historical Report, June 1969, box 2, volume 4, folder 2, CHL, LR 10539 2; Alberta Branch Manuscript History and Historical Reports (hereafter ABMHHR), 31 December 1973, CHL, LR 10538 2.

[52] Northwest Territories District Historical Information, CDOL, last updated 3 December 2010, cdol.lds.org.

[53] Letter, J. Talmage Jones to Frank Shields, 10 June 1965, WCMMPP, box 1, folder 6, CHL, LR 10539 25.

[54] ABMHHR, 31 December 1973, CHL, LR 10538 2.

[55] Sean Haslam, telephone interview with Carma Prete, 19 August 2015.

[56] Haslam interview, 19 August 2015.

[57] Haslam interview, 19 August 2015.

[58] Yellowknife Branch Historical Information, CDOL, updated 8 February 2014, cdol.lds.org.

[59] Changes in Mission Leadership, New Leaders Called in 1988, Canada Calgary Mission annual historical reports (hereafter CCMAHR), folder 1986–1988, CHL, LR 10539 3; “The Largest Branch in the World,” Ensign, September 1988, 43.

[60] “The Largest Branch in the World,” Ensign, September 1988, 43.

[61] Katie Malloy, “Mormons Come Knocking,” Yellowknifer, 24 May 1989, inserted into CCMAHR, folder 1989, CHL, LR 10539 3.

[62] CCMAHR, folder 1 (1986-1988), 1988, 2-3, CHL, LR 10539 3.

[63] Yellowknife Branch Historical Information, CDOL, last updated 26 August 2016, cdol.lds.org; CCMAHR, folder 1990-91, 4–5, CHL, LR 10539 3.

[64] CCMAHR, 1993, CHL, LR 10539 3.

[65] CCMAHR, October 1996, folder 1993, subfolder 1996, CHL, LR 10539 3.

[66] Canada Edmonton Mission Annual Historical Reports (hereafter CEMAHR), folder 1, 1998, CHL, LR 2010674 3.

[67] Yellowknife Northwest Territories Family History Center General Information and Contact Information, CDOL, last updated 6 August 2013, cdol.lds.org.

[68] Ryan Silke, “The Operational History of Mines in the Northwest Territories, Canada: An Historical Research Project,” 2009, 112, 246; “Mines Actively Producing in the NWT and Nunavut,” NWT & Nunavut Chamber of Mines, www.miningnorth.com/

[69] CEMAHR, folder 2011, CHL, LR 2010674 3.

[70] Stake history interview, 20 August 2013, EANSAHR, folder 2013, CHL, LR 378089 3.

[71] Thomas and Georgia Juanita Garrett, interviewed by Carma and Roy Prete, 29 August 2014.

[72] Garrett, “Cold to Serve,” October and November 2012.

[73] Garrett, “Cold to Serve,” November 2012 through June 2013.

[74] Nunavut—Quick Facts, Location and Land, World of Education, http://

[75] “Nunavut, facts about the territory in northern Canada,” www.aitc.sk.ca/

[76] Sara Minogue, “Mormon Missionaries target Iqaluit,” Nunatsiaq News (Iqaluit, Nunavut), 8 October 2004, http://

[77] Canada Montreal Mission Annual Historical Reports (hereafter CMMAHR), folder 4, 2004, CHL, LR 13768 3.

[78] CMMAHR, 2005–2006, folder 5, CHL, LR 13768 3.

[79] Iqaluit Branch Historical Information, CDOL, last updated 23 February 2009, cdol.lds.org.

[80] CMMAHR, 2005–2006, folder 5, CHL, LR 13768 3.

[81] Iqaluit Branch Historical Information, CDOL, last updated 23 February 2009, cdol.lds.org.