Samuel Brannan and the Eastern Saints

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 11–22.

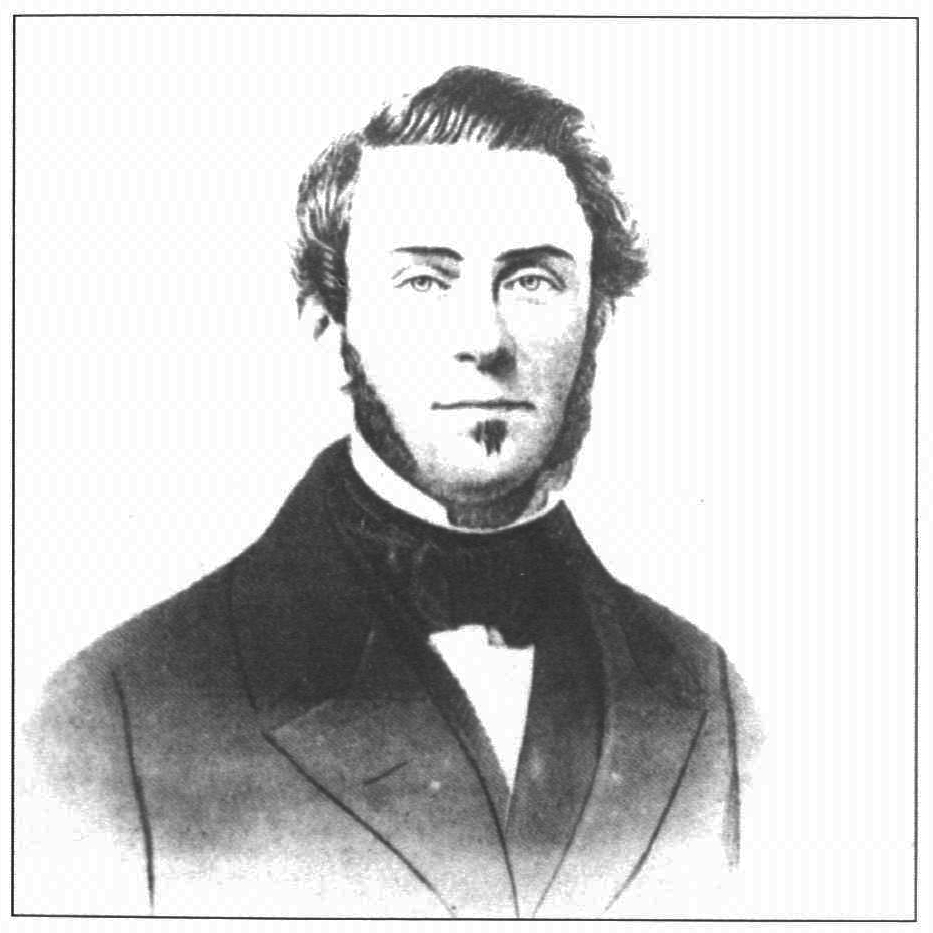

As the Book of Mormon was being distributed throughout the eastern United States by missionaries and others, not all converts gathered to the Midwest. A substantial number remained in the New England and Central Atlantic states. Some descended from a long line of American Pilgrims, pioneers, and patriots. Others were first-generation Americans or immigrants from Europe. Perhaps few individuals then had a greater impact on the lives of Church members in the eastern United States than the gifted young man, Samuel Brannan.

Samuel Brannan

Samuel Brannan

The Early Years

Brannan was born on 2 March 1819 in Saco, a town near the southern coast of Maine. He spent his entire childhood there. His family’s religious background is not known. He was the son of a hard-drinking, sometimes cruel father and a somewhat kinder mother.

Perhaps to remove Samuel from this less-than-desirable home or to have another able-bodied young man to help them in a new wilderness home, Samuel’s older sister, Mary Ann, and her husband, Alexander Badlam, took him with them when they moved to northeastern Ohio. They settled at Painesville, only a few miles from the Latter-day Saints’ center at Kirtland. Upon their arrival in 1833, fourteen-year-old Samuel became apprenticed to a printer. Just when he became a Latter‰day Saint is not known. However, at age sixteen he was among some one hundred who had worked on the Kirtland Temple and were blessed by Joseph Smith on 7 March 1835. [1]

After completing a three-year apprenticeship, Brannan became involved in a prevailing spirit of land speculation and sustained a “temporary loss” when things went amiss during the nationwide depression of 1837. [2] Kirtland tax records indicate that eighteen-year-old Brannan sold fifteen acres which he and another individual owned there. [3]

As he became an adult, he wanted to see other parts of the country. During the next few years, by his own report, he “visited every State in the Union.” [4] He traveled to New Orleans, where he was reunited with his brother, Thomas. They purchased a press and launched a weekly publication. Three years later, an outbreak of malaria took Thomas’s life and, with it, their publishing venture.

Thomas’s death changed Samuel’s plans. Taking whatever printing jobs he could find, he began working his way up the Mississippi. Eventually, he returned to Painesville, where he met and married Harriet Hatch. Soon a daughter was born; however, the marriage was unhappy and quickly ended in separation. [5] He was also called as a missionary to southern Ohio, where he met with some success before his mission was cut short by his own bout with malaria.

Mission Among the Eastern Saints

After recuperating from malaria, Brannan went to Nauvoo, from where the leaders of the Church sent him to New York City to assist with a Latter-day Saint newspaper for the Eastern States Mission. [6] During this early period of Church history, it became customary to hold general conferences at Church headquarters twice a year, in April and October. The Church’s missions held corresponding local conferences. The April 1844 conference of the Eastern States Mission in New York City approved Elder G. T. Leach’s proposal to publish a weekly paper to make known the principles of the Church. Subsequently, the first issue of The Prophet appeared on 18 May, published at 7 Spruce Street by “The Society for the Diffusion of Truth/’ with Leach as its president. [7]

Leach edited the first few issues. In the fall, mission president William Smith, brother of the recently slain Prophet, succeeded Leach, with Brannan as publisher. Then, beginning with the 23 November issue, the newspaper listed Samuel Brannan as both editor and publisher.

While in the East, Brannan met a boardinghouse proprietress, Fanny Corwin, and her daughter, Eliza Ann. [8] He fell in love with “Lizzie” and soon married her.

In addition to his editorial responsibilities, Brannan often visited branches throughout the mission and solicited funds for the paper. Unfortunately, he created some problems while doing so. Elder Wilford Woodruff of the Twelve, who spent some time in the eastern states on his way to England, assessed conditions in the mission and found mischief afoot. On 9 October 1844, he wrote that “much difficulty appeared to be brewing in New York and Philadelphia.” William Smith, without Church sanction, had authorized Brannan to marry people for eternity. These two, together with George J. Adams, taught the doctrine of “spiritual wives”—that women could have sexual relations with any men they pleased. Elder Woodruff also observed that many of the eastern Saints thought the Twelve were aware of and condoned these activities. In a follow-up letter, he requested that an apostle be sent from Nauvoo to take charge of the mission. [9]

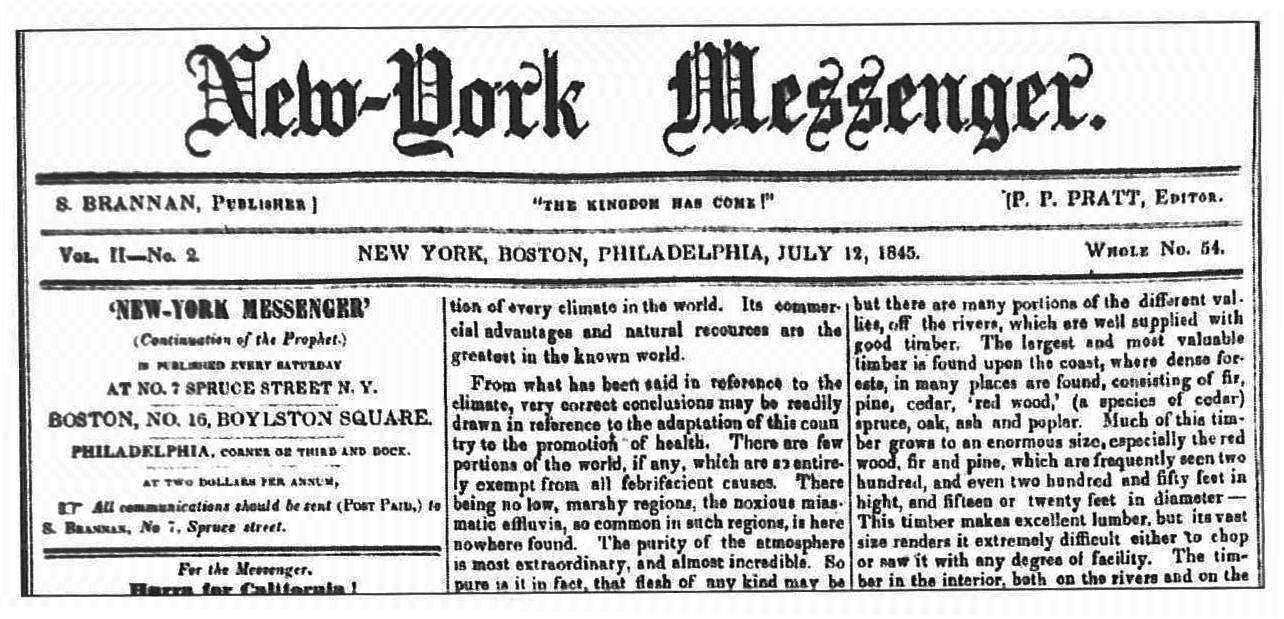

New-York Messenger, featuring information on California

New-York Messenger, featuring information on California

Elder Parley P. Pratt received this assignment and arrived in New York City in late December 1844. As he analyzed what was going on, he was astounded that “Elders William Smith, G. J. Adams, S. Brannan, and others, had been corrupting the Saints by introducing among them all manner of false doctrine and immoral practices.” Consequently, Elder Pratt sent Smith NEW-YORK MESSENGER, featuring information on California and Adams to Nauvoo, where they were cut off from the Church. However, in Brannan’s case, Elder Pratt merely warned the young man to “repent speedily of all such evil practices,” which Brannan promised to do. [10] Nevertheless, based on Wilford Woodruff’s earlier observations, leaders at Nauvoo disfellowshipped him. [11]

When a report of this disciplinary action reached New York, Elder Pratt urged Brannan to go to Nauvoo immediately and ask for reconsideration (an action Elder Pratt later came to regret; see chapter 11). Brannan promptly made the trip of over a thousand miles and arrived on 22 May. The next two days he met with the Twelve. After the matter was thoroughly investigated, they did not find his conduct as bad as had been reported and restored him to full fellowship. [12] He then returned to New York City.

Meanwhile, the last issue of The Prophet had appeared on 24 May (the very day Brannan had been restored to fellowship in Nauvoo). Under Elder Pratt’s direction, Brannan launched a new weekly paper, the New-York Messenger, beginning on 5 July. It was regarded as a continuation of The Prophet. Its first issue published a letter from Brigham Young and the Twelve reporting Brannan’s restoration to fellowship and encouraging the eastern Saints “to sustain him in his office, and in his Publishing department, and bless him with their faith and prayers.” [13]

Plans for Migration from New York

Soon after Brannan’s return to New York, Elder Orson Pratt of the Twelve replaced his brother as president of the Eastern States Mission, and Parley returned to Nauvoo. During this time Church leaders were deciding where the Saints would settle. On 15 September 1845, Brigham Young wrote to Brannan: “I wish you together with your press, paper, and ten thousand of the brethren were now in California at the Bay of St. Francisco, and if you can clear yourself and go there, do so and we will meet you there.” [14]

Such correspondence prompted increased discussion among eastern Saints concerning their own westward migration. The 1 November issue of the Messenger was filled with information and counsel concerning overland migration. The same theme continued into the first half of the next week’s edition. At that point, perhaps while the paper was actually being printed, Church leaders in the eastern states received instructions from “our worthy Presidents, the Twelve . . . to council us to make our journey to the place of our future destiny by water, as soon as arrangements can be conveniently made.” [15]

Thus, the second half of the 8 November issue announced: “We have ascertained that saints in the Eastern states can emigrate to the other side of the Rocky Mountains by water, with half the expense attending a journey by land, and they can take many things that could not be taken over the mountains.” The paper promised to discuss this plan further in future issues, and it did.

Following the apostles’ instruction, Elder Orson Pratt wrote a letter to the Saints that was published in the next edition. He admonished them to flee “as exiles from this wicked nation.” Those who could afford a more costly overland migration could go to Nauvoo and join the main body of the Church in its exodus. However, the poor would have to raise means to pay their passage by sea around Cape Horn to the western coast of North America. If enough chose to go by water, a ship could be chartered and the fare would be “scarcely nothing.” Elder Pratt encouraged them to leave as soon as possible in order to sail around Cape Horn during the Southern Hemisphere’s summer months.

“Elder Samuel Brannan is hereby appointed to preside over, and take charge of the company that goes by sea,” Elder Pratt continued, “and all who go with him will be required to give strict heed to his instruction and counsel.”

“Do not be faint hearted nor slothful,” he counseled, “but be courageous and diligent, prayerful and faithful, and you can accomplish almost any thing that you undertake. What great and good work cannot the saints do, if they take hold of it with energy, and ambition? Brethren awake!—be determined to get out from this evil nation next spring,” he exhorted. “We do not want one saint to be left in the United States after that time. Let every branch in the East, West, North, and South, be determined to flee out of Babylon, either by land or by sea.” [16]

Accordingly, the eastern Saints met at American Hall in New York City on 12 November 1845 and unanimously approved Elder Pratt’s instructions. It must have been difficult for the Saints to turn their backs on a country which their ancestors had fought to secure as a land of freedom and opportunity. And yet, the promised justice for all seemed not to apply to Latter-day Saints, as was pointed out by Brannan in the following resolution he presented to the conference:

Whereas, we as a people have sought to obey the great commandment of the dispensation of the fullness of times, by gathering ourselves together; and as often as we have done so, we have been sorely persecuted . . . our houses burned, and we disinherited of our possessions, . . . And . . . inasmuch as the people and authorities of the United States have sanctioned such proceedings without manifesting any disposition to sustain us in our constitutional rights, . . . Resolved, That we hail with joy the Proclamation of our brethren from the City of Joseph [Nauvoo] to make preparations for our immediate departure, . . . Resolved, that the church in this city [New York] move, one and all, west of the Rocky Mountains, between this and next season, either by land or water; and that we most earnestly pray all our brethren in this eastern country to join with us. [17]

The conference, comprised mostly of United States citizens, also unanimously approved this resolution to forsake their country. Brannan then invited all who wanted to go with him on the ship to come forward and sign up. Thus was his leadership established. His potential was reflected in his receiving stewardship, at the age of only twenty-six, for the lives of all who would sail with him.

Brannan’s young printer apprentice, Edward Kemble, described his employer as a “hard featured man” who, despite being “debilitated by a long attack of Western fever [malaria],” was nevertheless “a power” among his flock. [18] He was described by others as energetic and fearless, with rough manners, but genial and generous, with a brilliant personality. [19] He had the ability to express himself forcefully, and he possessed impressive personal charisma that made him a natural leader. Nevertheless, because he was impulsive and quick-tempered, he was unable to successfully arbitrate disputes among members of his company.

A Challenging Task

As the Saints returned home following the conference in November 1845, they must have considered the enormous significance of the pledge they had made. Some perhaps reflected on the voyage of their Pilgrim forebears. They, like their Latter-day Saint counterparts, were members of an unpopular religious group who became exiles sailing in a small ship to an unknown and untested destination. The 120 Plymouth Pilgrims were under the spiritual leadership of William Brewster, a seasoned, schooled, and respected man in his fifties who had served in the queen’s court. In contrast, there would be twice as many Saints setting out on a voyage five times as long and led by Samuel Brannan, who was half Brewster’s age and had much less experience. And they, unlike the well-organized and well-funded Pilgrims, had no backup help or support. The Saints’ voyage of 18,000 miles (which actually became 24,000 miles) was perhaps the longest religious sea-pilgrimage in history.

Left largely to his own devices in New York, young Samuel Brannan faced an almost superhuman task. Time was short. A ship had to be ready to sail in only about two months and in the middle of winter. The voyage around the tip of Cape Horn was treacherous. No restrictions were imposed regarding the age or health of potential passengers. Brannan had to convince a sufficient number of Saints to place themselves at the mercy of a potentially hostile captain and crew at a time when anti-Mormon sentiment and persecution were widespread. Being on a ship at sea, there would be little margin for error. They could not be certain they would be granted landing privileges in Mexican-controlled California. The passengers would be confined to close quarters for nearly six months, possibly leading to disagreements and temptations. They would have no contact with general Church leaders for nearly two years. Finally, most of the Saints were too poor to pay their passage.

Perhaps most problematic of all, Samuel Brannan—young, brash, articulate, and arrogant—had no experience at sea or in leading any group of people. Yet the voyagers’ very lives depended on his attention to the smallest detail, both at sea and in an unknown wilderness destination. Just why they were left at such a critical moment with unseasoned leadership is not clear. Perhaps Brannan, despite his weaknesses, was the best available.

Regardless of these many difficulties, many faithful eastern Saints began backing the spirit of the conference with solid actions. Possessions were sold as they assented to put their lives into Brannan’s hands to lead them to a place none had ever visited or seen. In the midst of the details Brannan attended to, he confided in a letter to President Brigham Young: “I feel my weakness and inability and desire your blessing and prayers that I may be successful. My cares and labors weigh me down day and night, but I trust in God that I shall soon have a happy deliverance.” [20]

The challenges faced by Brannan, Brigham Young, and the rest of the Saints were further complicated by a deteriorating international situation. Many in the United States believed it was the “Manifest Destiny” of the U.S. to occupy the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific. In July 1845, President James K. Polk, hoping to annex much of the Southwest, including California, ordered troops into territory claimed by Mexico. War was in the air. It was possible that the only welcoming party the Brooklyn would encounter would be the Mexican army or a gunboat ready to rebuff them. At this same time, American relations with Great Britain were also strained, because both powers wanted to possess the Oregon Territory.

In this potentially explosive climate, some government officials were concerned that because of the Saints’ mistreatment at the hands of their fellow Americans, they might go west and ally themselves with either Great Britain or Mexico. Certainly the New York Saints’ unanimous acceptance of Orson Pratt’s letter and Brannan’s resolution, each of which assailed the United States, made such an occurrence seem possible.

Church members, in turn, feared that the government might try to stop their emigration, whether by land or by sea. “I have received positive information,” Brannan wrote to Brigham Young, “that it is the intention of the government to disarm you after you have taken up your line of march in the spring.” [21] Church leaders therefore hesitated to divulge exactly where they were going. Despite the clarity of earlier communications to the Saints, they began a campaign of disinformation. For example, George A. Smith later recalled, “It was thought, proper not to reveal the secret of our intention to flee to the mountains; but as a kind of put off, it was communicated in the strictest confidence to General Hardin, who promised never to tell of it, that we intended to settle Vancouver’s Island. This report, however, was industriously circulated, as we anticipated it would be.” [22]

Brigham Young was reluctant to disclose his full intentions for the main body of the Church even to leaders like Brannan, as illustrated by the following exchange:

Brannan: Where are you going to settle?

Young: “I will say we have not determined to what place we shall go, but shall make a location where we can live in peace.”

Brannan: How soon will you leave?

Young: “When the grass is sufficient.”

Brannan: What will be your route?

Young: “The best route we can find.”

Brannan: How many are going?

Young: “Uncertain but all . . . are [of] a mind to go.”

Brannan: How long will the journey take?

Young: “I will tell you when we get to the end.” [23]

Thus, Brannan and his company did not know with any certainty what the Church’s final destination would be. Later, one of the group, John Horner, recalled that “the Twelve counseled the eastern Saints to charter a ship, get on board, and go around Cape Horn to upper California, find a place to settle, farm and raise crops, so that when the Church pioneers should arrive there the following year they would find sustenance.” [24]

As he pondered what to do with Brannan’s press, Orson Pratt wrote to Brigham Young: “Brother Brannan thinks it will be difficult to take his printing establishment and go to California unless he goes away dishonorably without paying debts. . . . He is very anxious to go and is willing to do anything he is counseled. He says that the church perhaps would consider it wisdom to buy his establishment and still keep up the paper.” [25] As things worked out, Brannan took the press with him. No one could have imagined the key role that it would play in American history.

Notes

[1] History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2d ed, rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 2:205–6 (hereafter HC).

[2] Samuel Brannan, “A Biographical Sketch Based on a Dictation,” 2, MS, C-D 805; Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley.

[3] Milton V. Backman jr., A Profile of Latter-day Saints of Kirtland, Ohio and Members of Zion’s Camp 1830–1839 (Provo, Utah: Department of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University, 1982), 135.

[4] Brannan, “A Biographical Sketch,” 3.

[5] Keva Scott, Samuel Brannan and the Golden Fleece (New York: Macmillan, 1944), 42. Scott indicates that she relied on family interviews and traditions for her fictionalized biography. According to Will Bagley, who is preparing a biography of Brannan, no other documentation has been found concerning this first wife.

[6] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1930), 3:38.

[7] T/;c/

[8] This name has also been given as Ann Alexia and Elizabeth Ann.

[9] Journal History, 9 October 1844, 22 October 1844, 3 December 1844; LDS Church Archives.

[10] Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1938), 37–38.

[11] HC 7:395.

[12] Brigham Young to Parley P. Pratt, 26 May 1845, Brigham Young Papers; LDS Church Archives.

[13] New-York Messenger, 5 July 1845.

[14] Brigham Young to Samuel Brannan, 15 September 1845, Brigham Young Papers; LDS Church Archives.

[15] New-York Messenger, 15 November 1845.

[16] Ibid.; see also HC 7:515–19.

[17] HC 7:520–21.

[18] See Edward Cleveland Kemble, “Twenty Years Ago,” Sacramento Daily Union, 11 September 1866, and A Kemble Reader: Stories of California, 1846–1848, ed. Fred Blackburn Rogers (San Francisco: The California Historical Society, 1963), 14.

[19] Stewart H. Holbrook, The Yankee Exodus (New York: Macmillan, 1950), 149.

[20] HC 7:588.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Journal of Discourses (Liverpool: F. D. Richards, Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1855–86), 2:23.

[23] Brigham Young to Samuel Brannan, 26 December 1845, Brigham Young Papers; LDS Church Archives; quoted in Ronald K. Esplin, “‘A Place Prepared’: Joseph, Brigham, and the Quest for Promised Refuge in the West,” Journal of Mormon History 9 (1982): 102–3.

[24] John M. Horner, “Voyage of the Ship ‘Brooklyn,” Improvement Era 9, no. 10 (August 1906): 795.

[25] HC 7:509.