Building Bridges: 1984–96

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 381–400.

The continued multiplication of stakes and missions created a significant Churchwide challenge. The long-standing structure of stake and mission presidents reporting directly to the apostles was stretching the Twelve beyond reasonable limits. Other levels of administration had to be put into place. The 1976 organization of the first Quorum of the Seventy and the subsequent formation of a Second Quorum gave the Church an administrative structure well suited for growth and expansion far into the future.

In 1984 the Church was divided into thirteen (later expanded to over twenty) large areas, and three men from among the Seventies quorums were called to preside over each as presidencies. California and Hawaii became the North America West Area, with Robert L. Backman as president, and native Californians Paul H. Dunn and John K. Carmack as counselors. This was a most significant milestone, because for the first time since 1923, when the Los Angeles Stake had been separated from the California Mission, all of the Golden State was included within a single ecclesiastical subdivision under one presidency.

One major challenge faced by the new area presidency—indeed by the Church as a whole—was that of building bridges to more people, including the growing numbers who spoke little or no English.

Changing Demographics

Internal U.S. migration to California finally slowed during the early 1970s, with 300,000 entering and 350,000 leaving in 1972. [1] However, this slow-down in growth was short-lived. The century-old vision of California as the promised land was just reaching such far-off places as the Middle East, India, China, and the Pacific Islands. Unprecedented numbers from those regions began joining the long-term flood into the state. Neighborhoods began looking like a miniature United Nations as Anglos, Blacks, Hispanics, and various Asian families lived together in close proximity.

Not only were the numbers large, but California was more culturally diverse than ever. The Anglo majority that had prevailed for nearly 150 years became a minority in some urban areas. Los Angeles’s 1990 population was 40 percent Hispanic compared to only 36 percent Anglo; 14 percent was African American, and 10 percent Asian.

The shift in San Jose was particularly dramatic. Between 1980 and 1990 the Hispanic population increased from 23 percent to 27 percent, while the Asian population expanded from 8 percent to 20 percent. Reader’s Digest remarked that “America [particularly California] is experiencing the biggest influx of immigrants since the great wave that ended in the 1920s. . . . It’s becoming a new America. . . . Let’s call it the ‘Sunday stew’—rich, various and roiling, and all of it held together by a good strong broth.” These immigrants “paid us the profoundest compliment by leaving the land of their birth to come and spend their lives with us.” [2]

Typically these newly arrived groups brought a strong sense of ethnic identity and pride. While this provided newcomers with a sense of security, it sometimes stood in the way of their assimilation into the larger society. The Church faced the challenge of helping these peoples maintain their cultural traditions while melding into a new community. Urban LDS congregations became dotted with many cultures. On one Sunday in the late 1980s, for example, San Jose’s Almaden Second Ward had four young priests prepare and administer the sacrament: one White, one Black, one Hispanic, and one Chinese. All later served missions.

During these same years many families moved to the suburbs. Some central urban stakes were left with only a dozen or so Aaronic Priesthood youth, a thousand or more widows, and thousands of other singles and retirees. What had been homogeneous wards of close-knit, white, middle-class families originally from Utah became heterogeneous wards of less-affluent ethnic peoples, mobile singles, and senior citizens. In 1974, of the 3,571 members in the Los Angeles Stake, for example, “almost one thousand belonged to the student wards, the singles branch, the Deaf Ward, or the Spanish Branch,” showing how diverse this stake had become. And “60 percent of the families had no Melchizedek Priesthood holder in the home, a statistic that reflected not only the growing number of widows but also the consequence of so many marriages outside the faith.” [3]

In November 1958, Church officials had given approval to disband the downtown Adams Ward in Los Angeles and dispose of its chapel. The historic mother ward of Los Angeles, which traced its roots back to the first Los Angeles Branch in 1895, and its building, the first urban LDS chapel in California, were no longer needed. The building’s beautiful stained-glass window was eventually acquired by the Church Museum of History and Art in Salt Lake City (see photo on page 2).

Twenty years later, the same debate arose over the fate of the landmark Wilshire Ward chapel. This time stake leaders saw “the future of the chapel as sound and exciting. . . . It was being used more than ever before, and by a wider variety of people.” While Anglos were moving out of the ward, “other groups such as Blacks, Koreans, Filipinos, and Latins were filling the v o i d . . . . It was clear that the chapel’s best days could still be ahead.” Instead of tearing the building down, a sum of one hundred thousand dollars was spent renovating it.

Stake president John Carmack received “a powerful spiritual confirmation of the decision. . . . A vision came to him in which he saw that while the building then served as a home for only one Spanish-speaking branch, it would one day serve many Spanish wards and be a center of Spanish activity.” [4]

In some ways, these two buildings epitomized the early twentieth-century Church, deeply intertwined with a Utah heritage, and mostly White. The demise of one building and renovation of the other underscored the fact that Mormonism was no longer a religion of Utahns or Anglo Americans but a church for “all nations, kindreds, tongues and peoples” that would find new ways to minister effectively to them.

Diverse Ethnic Congregations

Ethnic branches were not new, dating back to pioneer times in Utah. Yet Church leaders pondered whether it was better to have separate, non-English-language branches or to expect ethnic groups to blend into the established Englishspeaking units. Within the Church, some Anglo members found it difficult to adjust to the changes that immigrants were bringing. By the 1970s, Church leaders became convinced that it was important to make the gospel available to groups of new arrivals in their own language and to help them develop their own leaders. [5]

In the San Jose Stake, an independent Spanish-speaking branch had sacrificed over the years to build, from meager means, their own building, only to have the branch disbanded, its members assigned to English-speaking wards, and the building taken over by the stake for a genealogical library. However, when attendance at English-speaking meetings plummeted, a Spanish-speaking bishop was called, a Spanishspeaking ward organized, and their building partially restored to them. Church activity among this language group again blossomed.

Meanwhile other ethnic groups also proliferated in California. As the Vietnam War came to a close during the mid-1970s, many Southeast Asian refugees poured into the state. Local LDS congregations in several areas launched efforts to reach out to these newcomers. As a result of efforts by Latter-day Saints in Stockton, some 143 refugees from Laos and Cambodia attended Church services one Sunday early in 1981. [6]

Similarly, in Long Beach a Cambodian family and several friends responded to a missionary’s invitation to attend church even though they could not speak English. The Saints’ warm welcome encouraged more to attend, and after six weeks the number of Cambodian visitors passed the hundred mark.

Surprisingly, an inactive member who knew Cambodian was discovered right in the neighborhood. As he was enlisted into service, his faith revived, and soon he was sustained as a counselor in the newly formed branch presidency. Although most of the children could not speak English, they learned to sing some songs in that language. [7]

By 30 October 1966, an independent Spanish-speaking branch had been formed in the Los Angeles Stake. As this and other branches gained leadership strength, the time came to consider forming an entire ethnic stake. Since Spanish-speaking members constituted the largest ethnic minority, it was fitting that they should be the first to achieve that milestone.

“As early as 1972, a recommendation was made that a Spanish-speaking stake should be created in Los Angeles.” [8] Finally on 3 June 1984, Spanish Saints from the Huntington Park, Inglewood, Los Angeles, and Santa Monica Stakes crowded in the Huntington Park stake center for the momentous occasion. Presiding was Elder Howard W. Hunter of the Council of the Twelve.

The new Huntington Park West Stake, with seven wards, had a membership in excess of twenty-two hundred. The stake president was Rafael Seminario, former bishop of the Los Angeles Third Ward. He thanked the Anglo members who had helped his Spanish brethren learn Church leadership and expressed confidence that the new stake’s members would be equal to the challenges they would face.

And challenges there were. Many Hispanic families had barely enough resources to survive. They worked hard and long hours at low-paying jobs. Yet they found the faith and strength to fill Los Angeles Temple sessions on Saturdays at 6 A.M.—often their only day off.

Even though many members had to rely on public transit, often involving several transfers, Spanish-speaking units averaged over 60 percent attendance at sacrament meeting before the stake was created and over 65 percent afterward. These figures stood in stark contrast to the surrounding Englishspeaking wards and stakes, where the average was around 40 percent. The Spanish-speaking stake accounted for over half the region’s baptisms—enough to create one ward per year. The Spanish-speaking Saints proved they were more than ready to shoulder stake responsibilities, because within a decade the original stake had become four.

The next ethnic group to be organized into a stake was the Tongans, who began settling in the Bay Area in the late 1950s. During the next third of a century their numbers grew to the point that in July 1991, Princess Salote Mafile’O Pilolevu Tuita came to San Francisco to help these Latter-day Saints celebrate the Church’s centennial in their homeland. She honored them by appointing Hengehenga (Joe) Tonga a matapule (“Talking Chief”). In attendance was Elder John H. Groberg, the General Authority who presided over Church affairs in California. He had been a champion of the Tongan people and a close personal friend of Princess Pilolevu since serving as a missionary and mission president in Tonga.

The new San Francisco East Stake was formed on 10 May 1992 from existing Tongan wards in Foster City, Millbrae, and Oakland. Like the Spanish-speaking members, the Tongans had higher-than-average temple activity and sacrament meeting attendance and were faithful tithe payers. They were also known for their great musical talent, as Tongan choirs often provided music for the Oakland Temple Christmas lighting ceremony and other special Church events.

The number of ethnic Latter-day Saints continued to grow even faster than Church membership as a whole. By the mid- 1990s, there were over two hundred of these congregations in California, approximately one-sixth of the total wards and branches in the state.

Responding in Times of Disaster

As the Church continued maturing in California, the state was struck by a series of natural disasters that included earthquakes, floods, fires, and drought in a seemingly endless succession. However, the Saints were prepared to build bridges by taking love and support to everyone affected, including those who knew little of Christianity and even less about the Church.

On 2 May 1983, at least eleven Latter-day Saint families lost homes in an early-evening earthquake that shook the town of Coalinga. The Saints were well prepared for this calamity because just the day before, the ward bulletin had outlined what should be done in case of an earthquake. Following these instructions, home teachers, visiting teachers, and priesthood leaders accounted for the safety of all Church members in the affected area within two hours. [9]

Then came the fires. In July 1985 at least two LDS families lost homes in a blaze near San Diego. A month later, a massive inferno swept through the Santa Cruz mountains in the north, destroying or damaging a half dozen homes among members of the Alma Branch. However, the branch united with the congregations of three other faiths to work side by side, coordinating cleanup and relief efforts among themselves and their neighbors.

This same mountain area was one which experienced heavy flooding the following winter. However, once again, Church units were well prepared to meet the needs of their members.

These disasters were just a prelude. On 17 October 1989 a powerful earthquake rocked the region just prior to the second game of the first-ever Bay Area baseball World Series. The seven billion dollars in property losses made it the costliest natural disaster in U.S. history.

Few escaped unaffected. Priceless heirlooms and glass tumbled from shelves and shattered on the floor. Chimneys were cracked and broken. Entire buildings were destroyed. Dozens of Latter-day Saint homes were leveled, including the Alma Branch president’s mountain home—a home that had earlier escaped the fires and floods. Approximately ten of the seventy-five LDS buildings in the quake zone suffered damage. However, the Oakland Temple, built on solid rock, escaped with only a few minor cracks.

In San Francisco’s hard-hit Marina Ward, several members were involved in dramatic rescues. “There was a real spirit of community among the ward,” commented San Francisco Stake president Quentin L. Cook. Bishop J. Stanford Watkins added, “We usually do home teaching by assignment, but when something like this happens, we do it just by natural Christian instinct.” [10]

Three Church members were among the seventy who lost their lives. Two members were killed in an Oakland freeway collapse. Another died in Santa Cruz when an old brick storefront collapsed.

When wildfires swept the hills surrounding Santa Barbara in late June 1990, fourteen Latter-day Saint families, including stake president Gerald Haws, lost their homes [11] Then, in October of the following year, a massive fire swept through the hills in Oakland, destroying hundreds of homes and leaving the city—which had not yet recovered from the earthquake—stunned. However, no members’ homes were lost and there was no damage to the temple. [12]

Looming in the background through all these problems was a ten-year drought that caused severe water rationing and widespread anxiety. The drought ended shortly after the Area Presidency called upon members statewide to fast and pray for rain.

A different kind of disaster hit Southern California in late April 1992. Eight Church members lost their businesses when riots swept south-central Los Angeles. Once again, the Los Angeles Stake had just conducted an emergency preparedness drill the Saturday before the riots broke out, so members were able to put the procedures into effect when the crisis occurred. Church members joined people of other faiths to preserve peace and order in their neighborhoods. “I found it inspiring and gratifying,” remarked Keith Atkinson, the Church’s Direc- tor of Public Affairs in California, “to see good-hearted people draw together to protect businesses and homes in their community.”

In the aftermath, hundreds of Latter-day Saint volunteers with brooms and rakes joined thousands of others in cleaning up the debris. One afternoon the Long Beach Stake was asked to provide meals for the police and National Guard who had been called in to secure the peace. By 4 P.M. spaghetti and other casserole dinners were delivered. The soldiers and police officers were happy to have good home-cooked food.

When Los Angeles Stake president Howard B. Anderson attended testimony meeting in the Korean branch, whose members had been hit particularly hard by the looting, he was amazed to hear them singing “Come, Come, Ye Saints,” with its affirmation “All is well, All is well.” He had always associated this hymn with the early Pioneers, but he added, “I will never hear that song again and not think of those Korean people and their upbeat attitude.” [13]

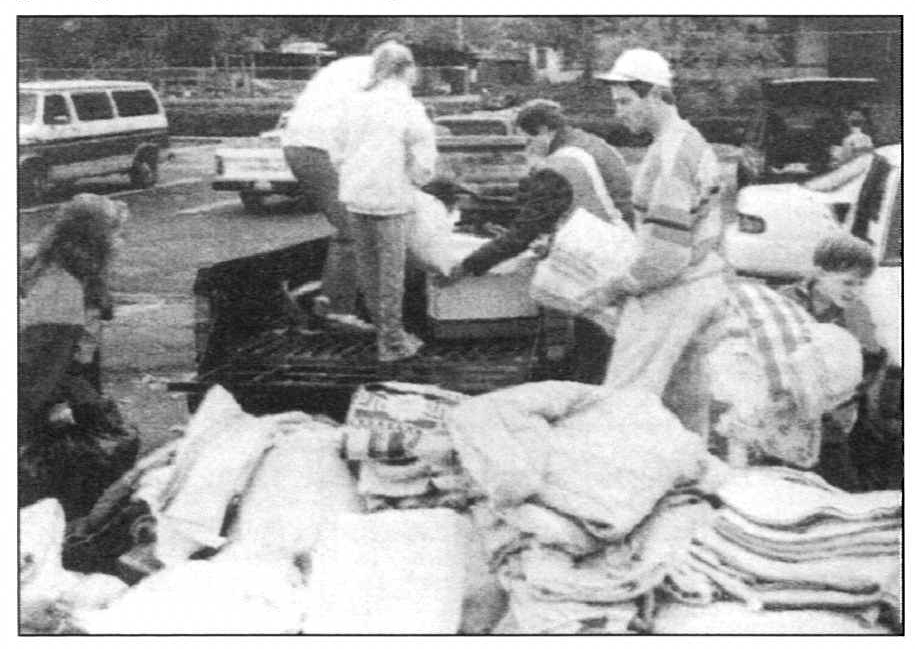

When floods hit Tijuana, Mexico, in January 1993, Latter-day Saints in the San Diego area offered a helping hand across the border, strengthening contacts between members in the two countries. A new bond developed with the construction of the San Diego Temple, when five stakes in northern Mexico were assigned to its temple district. It was through the temple committee that leaders in the United States first learned of the urgent needs in Tijuana. Within a few days a caravan of thirtyfive pickup trucks was on its way with forty to fifty tons of food and clothing to aid the Tijuana Saints and their neighbors. [14]

San Diego members gather relief supplies following Tijuana floods

San Diego members gather relief supplies following Tijuana floods

Continuing Efforts at Building Bridges

The Church also joined with others in promoting measures to improve the moral character of society. Pornography was a particularly offensive problem. Elder John K. Carmack, former Los Angeles Stake president and now a General Authority and a member of the area presidency, spoke before the California state legislature in favor of tighter laws. In 1990 the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors recognized the Church’s role in the passage of stiffer laws against child pornography: “Without the help of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and similar religious organizations you helped bring together, this bill would not have passed.” [15]

In the San Francisco Bay Area, a local effort at working with an interfaith group to broadcast religious programming caught the Church’s attention, and in September 1989 the Church joined a national coalition of twenty-eight religious groups in forming a national religious cable network known as VISN or Vision Interfaith Satellite Network (later renamed the Faith and Values Network). Leon Davies, who had been one of the founders of the Bay Area Religious Channel (BARC) was called with his wife on an indefinite mission to New York City to help launch the new national network.

California’s challenges also brought opportunities. After the 1989 quake, an interfaith group was organized in San Jose. Church representatives were welcomed, perhaps due to the enormity of the disaster and partly because religious leaders were divided over an anti-Mormon film that had been shown in some Protestant churches. Some ministers of other faiths embraced opportunities for friendship to counterbalance their colleagues’ involvement with the film. As earthquake relief efforts were carried out, new friendships were formed and new understandings reached, not only in San Jose but throughout the state, as Church leaders encouraged participation in interfaith groups wherever Latter-day Saints could be welcomed without compromising their principles or doctrine.

The Church has taught its members that their good example is the best way of sharing the gospel. For instance, Steve Young, a descendant of Brigham Young, became a star quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers. He not only became a favorite role model for Latter-day Saint youth, but he also attracted considerable goodwill for the Church.

Steve Young, San Francisco 49ers quarterback

Steve Young, San Francisco 49ers quarterback

Since its dedication in 1959, the Oakland Interstake Center on Temple Hill had been the focus of many Church and community programs, as well as home for three stakes, several wards, and a dozen or more small ethnic branches. Civic and other local leaders often referred to the Oakland Temple as “our temple.” Though few had ever been inside its walls or contributed to its construction or maintenance, the temple was nonetheless part of their community. It was the only Oakland landmark included in each of the convention and visitors bureau’s seven major city tours.

The Interstake Center was used for rescue operations after the devastating earthquake and fire. It seemed more than coincidence that during the city’s hours of crisis those administering physical and emotional relief wanted Temple Hill as a base of operations.

A new twenty-two-thousand-square-foot visitors center was dedicated on Temple Hill on 12 September 1992—a prototype of others to be built around the Church. Nearby residents were sent special invitations to be guests at an open house prior to its dedication. Like the city’s leaders, hundreds of citizens expressed their “ownership” of Temple Hill, citing the uplifting influence it was to them even though they were of other faiths or of no faith at all.

This center focused on the mission of Christ and the strengthening of families—two subjects which research showed were of interest to all people. The visitors center was built with large windows that took advantage of the magnificent view of the Bay Area. It featured a large statue of Christ and the latest interactive electronic displays that allowed visitors to hear answers to their questions about the Church. [16]

In the early 1990s, public affairs leaders began suggesting that the temple was the most visible, recognizable, and accessible symbol of the Latter-day Saint faith to those both inside and outside the Church. They recommended a program to bring more people to Temple Hill—qualified members to enter the temple itself, and others to at least come to the grounds where they could feel its influence. Outsiders had already recognized the Oakland Temple as a special place, as it had long been a popular backdrop for local Asian wedding pictures. Though non-Latter-day Saints could not enter the temple itself, almost every week an Asian wedding party would come and stroll through the grounds and take pictures with the temple in the background. They seemed to recognize instinctively that there was something special about marriage and the temple, even though most were not Christians.

After the new Oakland Temple visitors center was dedicated, public affairs missionaries—full-time couples having been called the previous year—moved into these facilities. Their efforts, together with the attractive new center, increased the number of visitors to the hill nearly fourfold, from 34,364 in 1991 to 126,313 two years later. In mid-1994, Temple Hill public affairs and cultural arts councils were formed to further promote activities there.

New Houses of Worship

A challenge posed by continued Church growth and increased attendance at meetings was the need for more houses of worship. A 1984 national survey revealed that in an average week, 53 percent of all Latter-day Saints attended worship services—the highest number of any religious group in the study. [17] The Saints’ increased faithfulness in paying tithes enabled the Church to more easily meet the need for more buildings. Over the years, local units had paid about 50 percent for the construction and maintenance of buildings. Beginning in April 1982 the Church announced that the local congregations’ share was being reduced. In California, members were amazed that during a time of rising prices and taxes, the Church was able to lessen the financial burden of its members.

In November 1989, the Church announced that all building construction and maintenance costs would be paid from general Church funds. This was a real boon to the growing number of poor urban ethnic congregations, as funds for Church buildings and programs were all allocated from Salt Lake City without regard to local financial circumstance. A major criterion for receiving funds was sacrament meeting attendance, something at which many ethnic congregations excelled.

Throughout the state, older buildings were expanded and refurbished at general Church expense, bringing all buildings to a standard of maintenance and building code compliance never before seen.

Further, the consolidating of meetings under the Church correlation program paved the way for more compact building designs, and local chapels were reduced in size from approximately nineteen thousand to fourteen thousand square feet. On the other end of the scale, large chapels, capable of housing an entire stake, appeared. The LDS pioneer town of Fremont soon boasted two of them—one on the north end of town and one on the south. Another was built on the southeastern edge of San Jose, where it was anticipated that city growth would eventually result in new wards needing a home.

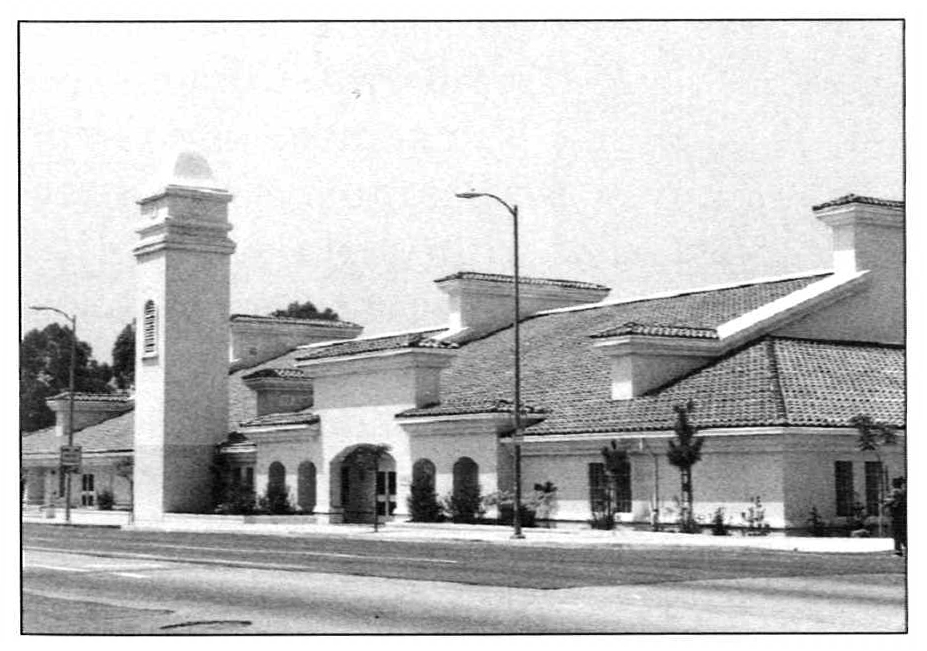

In Oakland, members of several ethnic branches attended services at the Inter stake Center on Temple Hill. But as they found it burdensome to travel across town, land was purchased to erect a new building for them in a more centrally located ethnic neighborhood. Likewise, following the riots in south-central Los Angeles, the Church was among the first to announce a new building in this district. It would be a large facility for the Spanish-speaking stake in the area. Such a thing would have been unthinkable just a few years before, and some grumbled at the Church for planning new buildings in what they perceived to be decaying neighborhoods.

Center for first Spanish-speaking stake in Los Angeles

Center for first Spanish-speaking stake in Los Angeles

However, some members, as well as other religious and civic leaders, expressed pride in a church that offered hope in areas where it was most needed. Many saw the Church’s action as a partial fulfillment of its mandate to be with and minister to people where they lived and as a sign that the Church believed in its ability to lift and bless people in every circumstance.

In addition, after the Los Angeles and Oakland temples had been in service for a quarter century, the time came for the facilities in each to be improved and expanded. The Los Angeles Temple was closed for an extended period in 1980–81, as was the Oakland Temple nine years later. In each case, additional rooms were provided for presenting the endowment, enabling a new session to begin every half hour. [18]

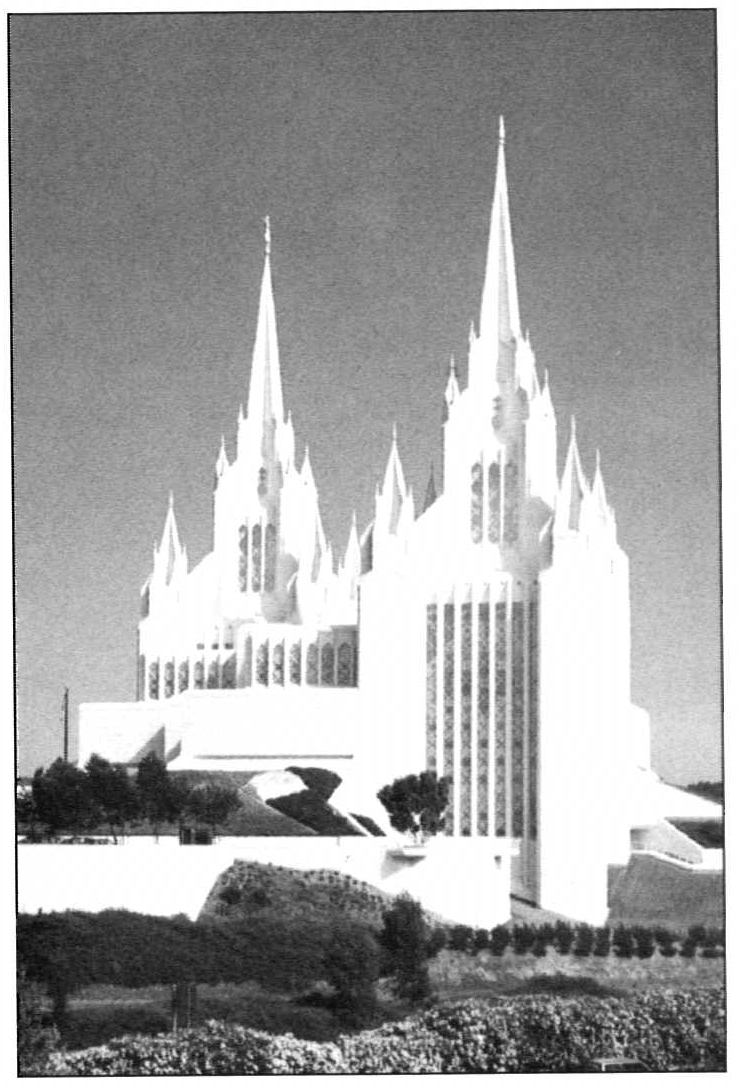

The San Diego Temple

The major building project during the twentieth century’s concluding decade was the construction of California’s third temple. As early as 1977, Donald R. McArthur, a regional Church official in San Diego, was impressed that a temple should be built on vacant property he had observed adjacent to the 1–5 freeway just south of La Jolla Village. Plans to construct a temple in San Diego were announced publicly in 1984, and the 6.9-acre site was acquired early the following year. One individual referred to the Church’s early practice of building temples on hilltops and declared the visible freeway site to be “the modern urban equivalent of those early temples.” [19] As had been the case with the Los Angeles and Oakland temples a quarter of a century earlier, the Saints in the San Diego Temple district raised 50 percent more funds than the assigned amount.

Ground was broken for the new temple on 27 February 1988, and actual construction commenced two years later. [20] The building gradually took shape in full view of tens of thousands traveling the 1–5 freeway each day. It has two towers, each 190 feet high, and a fourteen-foot-tall goldleafed statue of the angel Moroni surmounting the eastern spire. Gleaming white marble chips were blown into the temple’s exterior plaster to give the building a glistening look. The temple has a total floor space of fifty-nine thousand square feet, including four endowment presentation rooms.

San Diego Temple

San Diego Temple

In May 1992, as the temple neared completion, the First Presidency named Floyd L. Packard to be the temple president. At the same time, his brother, H. Von Packard, was named to preside over the Los Angeles Temple. Area president Elder John H. Groberg noted that “this is the first time in the history of the Church that brothers have simultaneously served as temple presidents.” [21]

Daily newspapers asserted that the $24.4-million LDS temple was “destined to become a San Diego landmark” and “a highly visible manifestation of the important contributions Mormons have made to San Diego for over a century.” [22]

A Jewish rabbi compared the temple to medieval cathedrals which used “architecture to create a space that invokes the celestial heavens that is awesome, that transcends the place and the moment, transporting people from the here and now to thoughts and images of God’s presence . . . . We thank [our Mormon friends] for reminding us how holy a place a mere building can be.” [23]

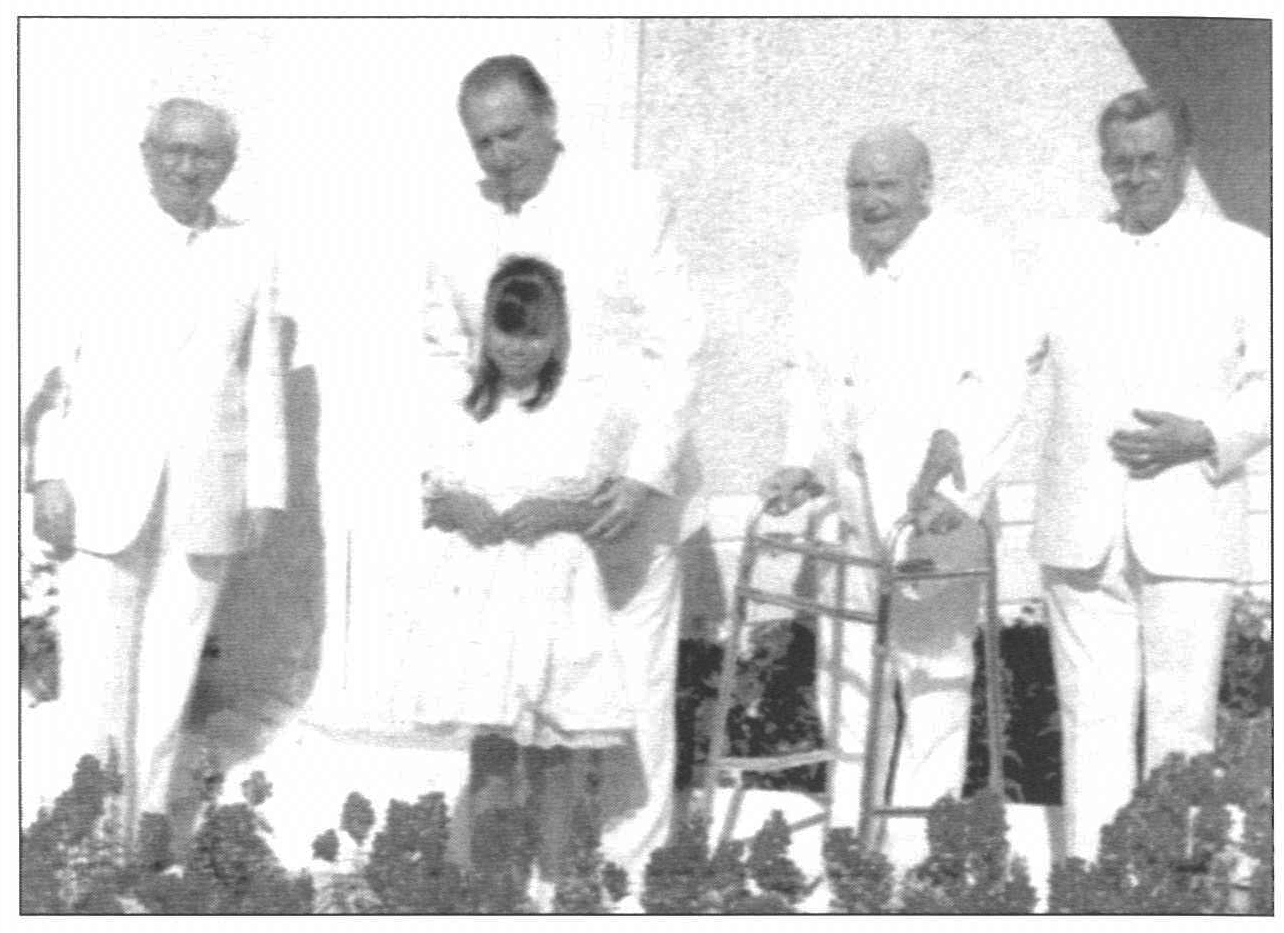

The temple was dedicated in twenty-three sessions beginning on 23 April 1993. President Gordon B. Hinckley, counselor to Church president Ezra Taft Benson, opened the dedication by declaring: “The significant things about this temple are the ordinances of the gospel that will be administered here. . . . There would be no purpose to build temples if there was no immortality.” [24]

Three dedicatory sessions were conducted in Spanish for the benefit of Church members from Mexico and Spanish-speaking Saints from Southern California. In two of these sessions President Hinckley “spoke with emotion” about the heritage of these Saints: “You come from two great ancestral lines, from the people of Spain and from the people of Jerusalem, Lehi and his children. Great is your inheritance and marvelous are your blessings. . . . You are a beautiful people . . . with beautiful testimonies, with the light of the gospel of Christ in your lives. You represent a miracle this day in the house of God. [You are] people who love the Lord and are loved by the Lord.” [25]

President Gordon B. Hinckley, Thomas S. Monson, Howard W. Hunter,

President Gordon B. Hinckley, Thomas S. Monson, Howard W. Hunter,

Elder Boyd K. Packer, and Susan Elizabeth Cardenas Vargas

at dedication of San Diego Temple

Bringing together not only the living and the dead but also the Anglo and Hispanic communities in its area, the San Diego Temple exemplified the connecting power of the Church. Building on foundations laid in earlier times, the Church in California reached out to build bridges of love and understanding. It sought to bless members of varied ethnic groups, to render assistance in the wake of disasters, and to help improve the moral climate of society and the quality of life for all. With visible and invisible bridges in place, the California Saints increasingly took advantage of opportunities to share their precious gospel treasure.

Notes

[1] T. H. Watkins, California: An Illustrated History (Palo Alto, Calif.: American West, 1973), 516.

[2] Reader’s Digest, July 1991, 39–40.

[3] Chad M. Orton, More Faith Than Fear: The Los Angeles Stake Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 275, 220.

[4] Ibid., 267–70.

[5] Church News, 17 June 1989, 8–9.

[6] Ibid., 21 February 1981, 13.

[7] Ibid., 17 January 1981, 7.

[8] Orion, 303.

[9] Church News, 8 May 1983, 13.

[10] Ibid., 28 October 1989, 3, 7–10.

[11] Ibid., 14 July 1990, 8, 10.

[12] Ibid., 26 October 1991, 5; 2 November 1991, 6.

[13] Ibid., 9 May 1992, 5.

[14] Ibid., 23 January 1993, 3, 5.

[15] Ibid., 5 December 1987, 5; 17 March 1990, 3, 13.

[16] Ibid., 19 September 1992, 3–4.

[17] Ibid., 10 February 1985, 3.

[18] Ibid., 14 March 1981, 11; 5 November 1988, 2.

[19] Los Angeles Times, 4 January 1993, A22.

[20] Donald R. McArthur, From Small Things: San Diego Stake, Its People and Its History (San Diego Stake, 1990), 287–96.

[21] The San Diego Seagull, April 1993, 30.

[22] San Diego Union-Tribune, 27 February 1993; San Diego Evening Tribune, 19 February 1993, B6.

[23] San Diego Jewish Times, 25 March 1993.

[24] Church News, 1 May 1993, 3.

[25] Ibid.