Acquiring Cumorah

Cameron J. Packer

Cameron J. Packer, "Acquiring Cumorah," Religious Educator6, no. 2 (2005): 29–50.

Cameron Packer was a seminary teacher at Orem Jr. High School when this was written.

Early Church member W. W. Phelps wrote, “Cumorah . . . is well calculated to stand in this generation, as a monument of marvelous works and wonders.”[1] With a stately monument of the angel Moroni cresting its summit and a yearly pageant commemorating salient events associated with the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, the hill is fulfilling the exact role that Phelps envisioned. However, the general population of the Church is relatively unfamiliar with the history of the acquisition of this significant Latter-day Saint landmark.

As a result of the religious experiences Joseph Smith had on the Hill Cumorah and the subsequent teachings of early Church leaders, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints naturally desired to visit the hill along with other sites belonging to the “Mormon culture hearth.”[2] Initially, the Latter-day Saints may have been content to just visit these sites; however, as the Church’s resources increased, so did the desire to own them. While the story of how The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints acquired the Hill Cumorah is historical in nature, it also manifests the intervening hand of Deity.[3]

Remembering the Beginnings

The experiences of Joseph Smith at the Hill Cumorah, along with the teachings and writings of the early leaders, effectively memorialized the hill in the minds of the Church members. One writer for the Deseret News wrote: “When Joseph Smith received the plates from Moroni, the Hill Cumorah had faithfully discharged its sacred trust, and as far as historical importance is concerned, ‘passed out of the picture.’ But not so in the memories of the thousands and thousands of people who have accepted the Gospel message and followed the inspired teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. To them it is and always will be a sacred shrine.”[4] Because this article reflected the growing attitude of Church members at that time, it is easy to see why the Saints in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries began traveling back to Palmyra to see the Hill Cumorah. From this time period, there are records of numbers of individuals who made the trek east, essentially enacting some of the first Church history tours. The Hill Cumorah was high on the list of “must sees” for these early Latter-day Saint pilgrims. One such visitor, James A. Little, reflected on the wellspring of feelings generated by his visit to Cumorah. He said, “On the 11th of last December I stood for the first time on the hill Cumorah. I had longed to see this spot, now associated in the minds of the Saints with the events of the deepest interest. I seemed impressed with an inspiration peculiar to the place. Although enveloped in a cold scudding snow storm, I was able to call up from the shadowy past some of the important events which have closed and commenced grand epochs in the history of the Western Hemisphere with a rapidity and vividness impossible to represent to others.”[5]

A few years after James A. Little’s visit to Cumorah, Elders Orson Pratt and Joseph F. Smith departed Salt Lake City for the East. On this journey they stopped at a number of Church history sites, and while in Kirtland they diligently sought to acquire “the mind of the spirit,” and concluded that while they were so near, they should visit the Hill Cumorah. In a correspondence to President John Taylor dated September 17, 1878, they wrote the following of their experience at Cumorah:

In a beautiful little grove on this memorable hill, we bowed in humble and fervent prayer, rendering prayer and thanksgiving to Almighty God for the treasure of knowledge and truth so long concealed beneath its surface, to be brought forth by the gift and power of God to us and the world in this dispensation. The spirit of prayer, of blessing and prophecy rested upon us so that we rejoiced exceedingly. After prayers we laid our hands upon and blessed each other, giving utterance as the spirit dictated. We spent several hours looking over the hill, viewing the surrounding country, in meditation, prayer, and thanksgiving. After which we drove to the little town of Manchester and returned to Palmyra, rejoicing and feeling that we had not spent our time in vain. We cut a few sticks from near the summit of the hill, which we brought with us as momentoes [sic] of our visit.[6]

Another notable Latter-day Saint, Susa Young Gates, daughter of Brigham Young, also found the Hill Cumorah to be a place of great significance. She recounted, “The drive around the north end of the Hill repaid us for coming; the mighty sentinel rises with a strength and majesty when you face him which impresses you with all the dignity and force of which an inanimate custodian is capable. What a rush of emotions filled my heart!”[7]

Perhaps the most significant of these visits or pilgrimages to the Hill Cumorah came shortly after Susa Young Gates’s trip, when Joseph F. Smith, as President of the Church, once again set foot on the slopes of Cumorah. In company with others, he traveled back to Sharon, Vermont, in December 1905 for the purpose of dedicating a monument commemorating the one hundredth anniversary of the birth of the Prophet Joseph Smith. On their return, President Smith and party stopped at the railway station in Palmyra, New York, and drove out to the Hill Cumorah. After climbing to its summit and discussing some of the history of the place, President Smith offered a prayer. As reported in the Deseret News, “[This prayer was a] comprehensive and splendid prayer, which brought tears to many an eye, and softened all hearts, evoking a unanimous Amen at the close. The party rejoiced exceedingly at this fresh manifestation of the presence of the Holy Spirit, testifying to the soul of the truth of the latter-day work and foretelling its ultimate triumph over all opposing powers.”[8] It is apparent from these accounts that many Latter-day Saint visitors had spiritual experiences that renewed their faith in the Restoration while visiting the hill wherein was found the keystone of their religion, the Book of Mormon.

By 1911 larger groups numbering around 200 to 250 Latter-day Saints were making their way to the Hill Cumorah.[9] The Palmyra newspaper headlines often portrayed these “pilgrimages” in an almost ominous, invasion-like tone.[10] However, these same newspapers at times portrayed a sense of hospitality and graciousness towards these Latter-day Saint pilgrims of the late 1800s and early 1900s.[11] This positive feeling reflected in the local newspapers, however, would noticeably cool with the arrival of a permanent Latter-day Saint presence in the area.[12]

A Foot in the Door

As a direct result of the Saints’ adherence to the law of tithing, the Church was able to remove itself from the bonds of financial debt by the beginning of the twentieth century. In the April 1907 general conference of the Church, President Joseph F. Smith announced, “Today the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints owes not a dollar that it cannot pay at once. At last we are in a position that we can pay as we go.”[13] This newfound financial freedom allowed the Church to further expand what had already begun as a limited and careful acquisition of selected Church history sites. Two months after President Smith’s declaration of financial freedom, Elder George Albert Smith purchased the one-hundred-acre Smith homestead near Palmyra, New York, from a man named William Avery Chapman. Because Mr. Chapman was getting too old and arthritic to run the farm himself, he decided to sell it to Elder Smith, with whom he had developed a friendship during many visits.[14] Although the purchased farm did not include the Hill Cumorah, this was the foot in the door that the Church needed in order to begin acquiring the hill and many other New York and Pennsylvania historical sites.[15]

One problem, as alluded to earlier, was a prejudice that had been festering in that region of the country for almost a century. Some citizens of the Palmyra-Manchester area had become embittered against the Latter-day Saints, as Susa Young Gates found out in her visit to the Hill Cumorah. Mr. George Sampson, who operated a farm embracing the north end of the hill and a significant portion of the east side, approached the party and, upon learning that they were Mormons, rudely stated, “Well, no Mormons can set foot inside my house. I know them all! They are a bad, wicked, deceitful lot; I know them, O, I know them. . . . Old Joe Smith and Brigham Young and the men that started this thing were rascals and scoundrels. I know them all, and a worse lot of men never lived.”[16]

Despite the antagonistic feelings against them, the Church still purchased the one-hundred-acre Smith farm in 1907 but allowed the current owner, Mr. William Avery Chapman, to move out on his own timetable. This turned out to be about seven years later. When in 1915 Mr. Chapman finally moved from the farm, it became necessary for the Church to find a man to move into the Smith home who could handle the local prejudice and hopefully begin changing the attitude towards the Church.[17]

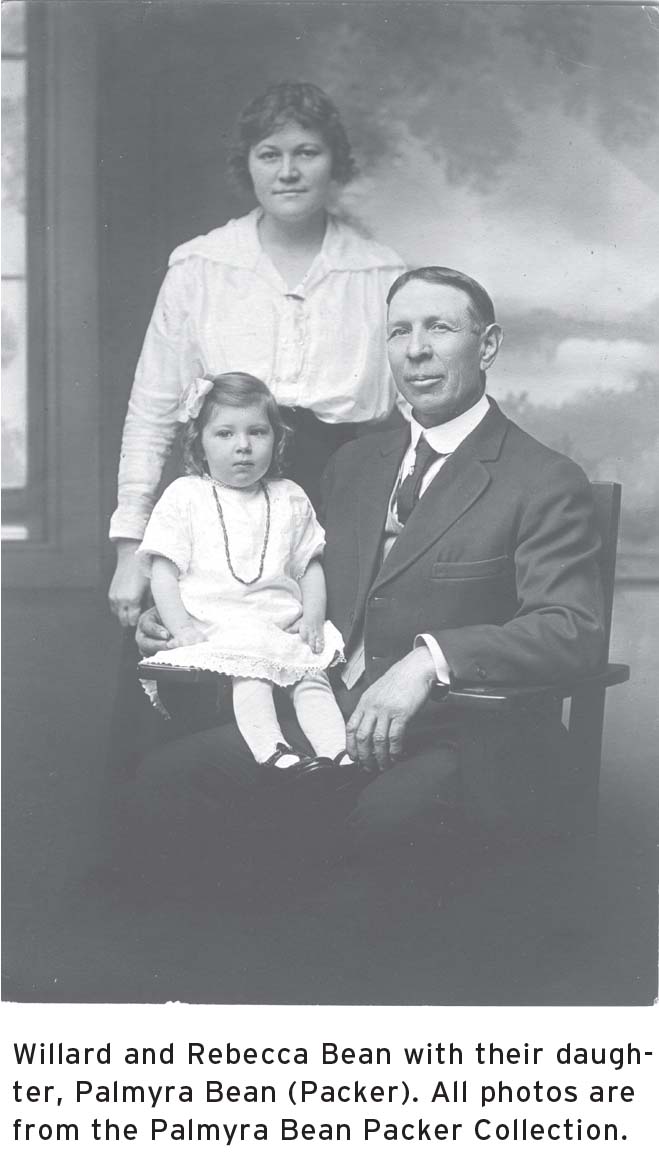

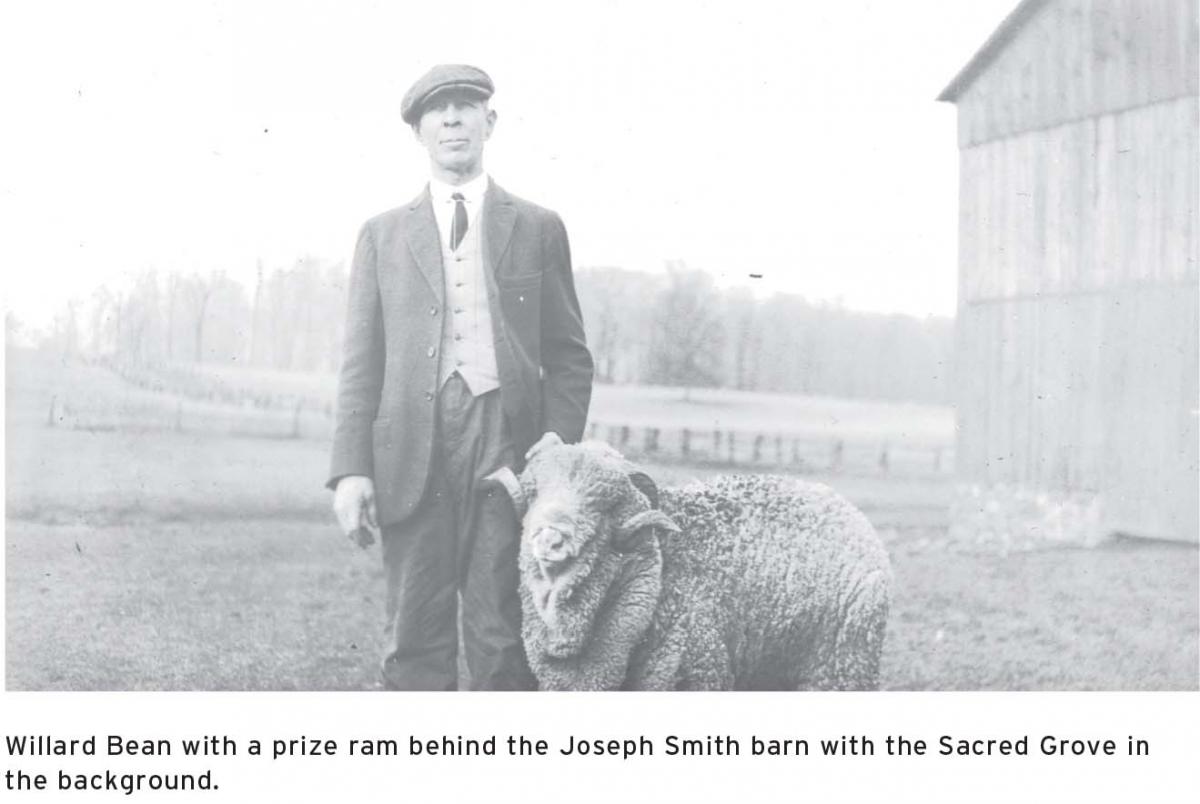

Willard Washington Bean

With this in the back of his mind, Elder George Albert Smith visited Richfield, Utah, in 1914 for a stake conference. While the Apostle was seated on the stand, a man by the name of Willard Washington Bean walked in the back. According to Elder Smith, “When [Willard] stepped in that door the impression was so strong it was just like a voice said to me, ‘There’s your man.’”[18] Willard Bean, a former boxer who had tutored the great Jack Dempsey, was a perfect match for the challenge. He had seen much of prejudice while serving a mission in the southern states and succeeded in winning friends from among those who at first were the most hostile towards the Church.[19] As a result of his unique personality and abilities, Willard Bean became a key figure in the Church’s acquisition of the Hill Cumorah and many other significant historical sites.

In 1915 Willard and his new bride, Rebecca, were set apart for their mission to Palmyra-Manchester by President Joseph F. Smith and told that they were heading to “the most prejudiced place in the world.”[20] This prophetic statement was fulfilled upon the Bean’s arrival in Palmyra. No sooner had they settled into the Smith’s Manchester frame home than a committee of townspeople was sent to inform them that they were to leave the area. Willard went out on the doorstep and said, “Well, now, I’m sorry to hear that. We had hoped to come out here and settle with your people and be an asset to this community, but I’m telling you we’re here to stay if we have to fight our way . . . . I’ll take you on one at a time or three at a time. We’re here to stay.”[21] Willard attributed the residents’ hostility to their embarrassment in being associated with the birthplace of a religion that had practiced polygamy and was politically unpopular.[22] As a result, several people with strong anti-Mormon feelings were hired to lecture to the community regarding the evils of “Mormonism.” The Bean children were ostracized at school, lies and rumors were spread, and life in general was made difficult for the family from Utah.[23] This treatment seemed to bring out the best in Willard Bean and even led to the first purchase of part of the Hill Cumorah. According to Willard: “When they began to abuse the Mormon people my fighting blood came to the surface and I didn’t hesitate to transfer it [the Smith homestead] over to the church. It was then that the Mormon Church was getting a foothold that might well become a problem and disgrace to the community. But I met the issue by negotiating for a slice of the Hill Cumorah.”[24]

The Purchase of the First “Slice” of the Hill Cumorah, 1923

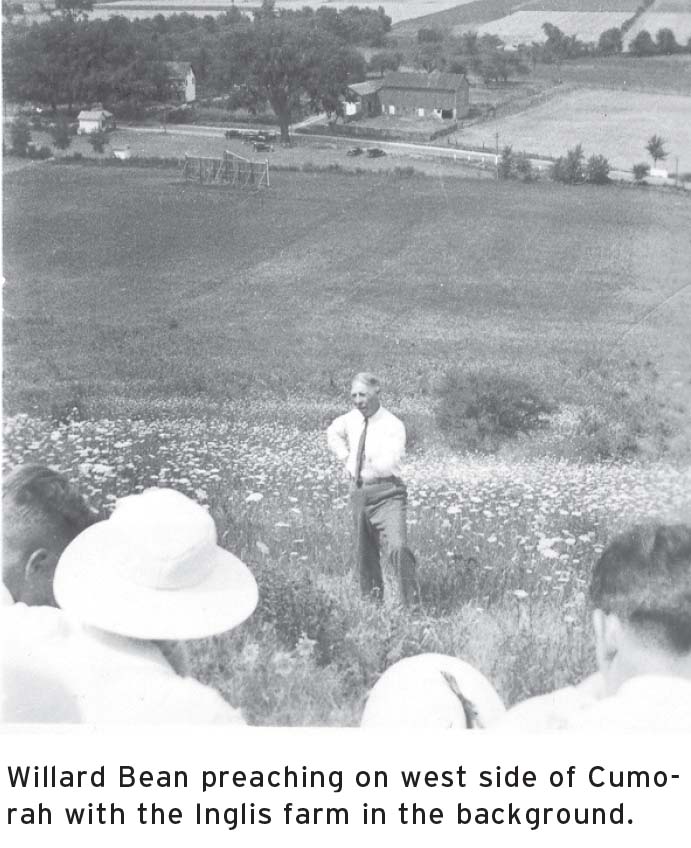

The first time the Beans visited the Hill Cumorah, they were met by a man holding a shotgun who said, “Nobody steps on this hill belongs to Mormon Church.”[25] But within about five years, Willard had become friendly with a man named James H. Inglis, whose farm included a small “slice of the Hill Cumorah.” The Inglis farm was ninety-eight acres and extended halfway up the west side of the Hill Cumorah and included “the entire apron or flat between the hill, and the highway.” Bean thought that if the Church were ever able to purchase the rest of the hill, they would certainly need this portion to be able to access it easily as well as provide parking space for visitors.[26] Therefore, it must have struck Bean as providential, when one day while they were visiting, Mr. Inglis said, “Let me sell you my farm. You will then be able to say that you own part of the hill at least.”[27] On June 19, 1923, Bean wrote to the Presiding Bishopric as follows:

I am writing you about a farm which I am fully convinced the church should acquire. Perhaps you will remember a beautiful, well kept farm at the foot of Cumorah hill taking in part of the foot of the hill proper. Infact [sic] the fence at the point of the hill runs probably 2/

3 of way up. The farm is a nicely kept, productive farm, has never been tenanted out, hence not run down, consisting of 90 acres practically all tillable. . . . Has a house of probably 12, or more rooms. At [sic] attractively located commanding beautiful view of west side of hill where the Plates were obtained, and on the state road where could do a big missionary work with tourists and others who stop to view and snap the hill.

He asks $11,000, for the property which is not above the market price. Infact [sic] when he told his neighbor that he had offered his farm for sale his neighbor thot [sic] him foolish as he asked $15,000 for his which has only 10 acres more and not as good a house.

I didn’t intend to bring this to your attention until fall when I plan to be to conference. But am most afraid it wont keep. Am afraid if it becomes rumored about that he has offeáred to me for $11,000 that some fellow, to be ornery, will grab it and then hold it for a fabulous price. And it seems to me that this is THE chance to get part of the Hill, thus gaining a foothold, at market value.[28]

However, by the time he obtained permission to proceed, Mr. Inglis’s wife had all but talked him out of selling the farm. Willard learned that at the time Inglis offered to sell, he was having difficulty with his hired help. But shortly thereafter, his old helper, who had been with him for nine years, returned to work for him again, which caused Inglis to rethink his offer.[29] Mr. Inglis, however, advancing in age and realizing that he had given his word, told Willard Bean that if he would purchase the equipment and livestock in addition, he would still sell him the farm. One more condition that Inglis requested was that the sale be done without any publicity because they expected some “criticism and scensure [sic] from their neighbors and friends” for selling to the “Mormons.”[30] This prompted Inglis to transfer the title to Bean rather than the Church. Although the price of the Inglis farm was $13,000,[31] the public records show the transfer of title on September 17, 1923, to Willard Bean for only one dollar.[32] Because New York is a “nondisclosure” state, Mr. Inglis was not required to publicly disclose the actual sales price of his farm. However, he was required to assign and disclose some monetary value to the transfer of title of the property to Willard Bean. He followed a longstanding legal precedent—still in effect today—that was to assign a value of one dollar to the property. This, along with requiring that Willard Bean be the buyer, ensured that public records would not disclose the actual amount for which he sold it.[33] Bean explained this procedure to the Presiding Bishopric as follows: “You will observe that had to make transfer to me first. That was not necessary but he was so afraid somebody would think he was selling to the Mormon Church and censure him.”[34] On the contrary, it surprisingly turned out that many of the Palmyra residents, by that time, had warmed up to the permanent Latter-day Saint presence in Palmyra and even wished the Church could obtain the rest of the Hill Cumorah. Bean wrote: “As soon as the paper announced the sale the business men and larger caliber citizens almost shouted for joy and wished that we could get the balance of the Hill and establish a Shrine here etc. etc. Every man who had a farm between us and the Hill came to me and wanted to sell. A hotel men [sic] in Palmyra got it into his head that we would even want a Hotel and offered to sell at a bargain.”[35]

Thus, within the space of eight years, the efforts of the Bean family resulted in at least a partial change of sentiment towards the Latter-day Saints and the purchase of part of the Hill Cumorah. President Heber J. Grant officially announced to the Church in the October 1923 General Conference the following: “We are now the owners of a part of the Hill Cumorah. The Church, a few weeks ago, purchased a farm of ninety odd acres, which embraces the West slope of the Hill Cumorah, about one-third of the way up the hill. There is a nice farm house, and it is a very fine piece of property. Elder Willard Bean, in charge of the Memorial Home, of the Smith Farm, wrote us that he could purchase this property, and we are glad that at least part of the hill is in the possession of the Church.”[36]

The Purchase of a Second Sizeable Portion of the Hill Cumorah, 1928

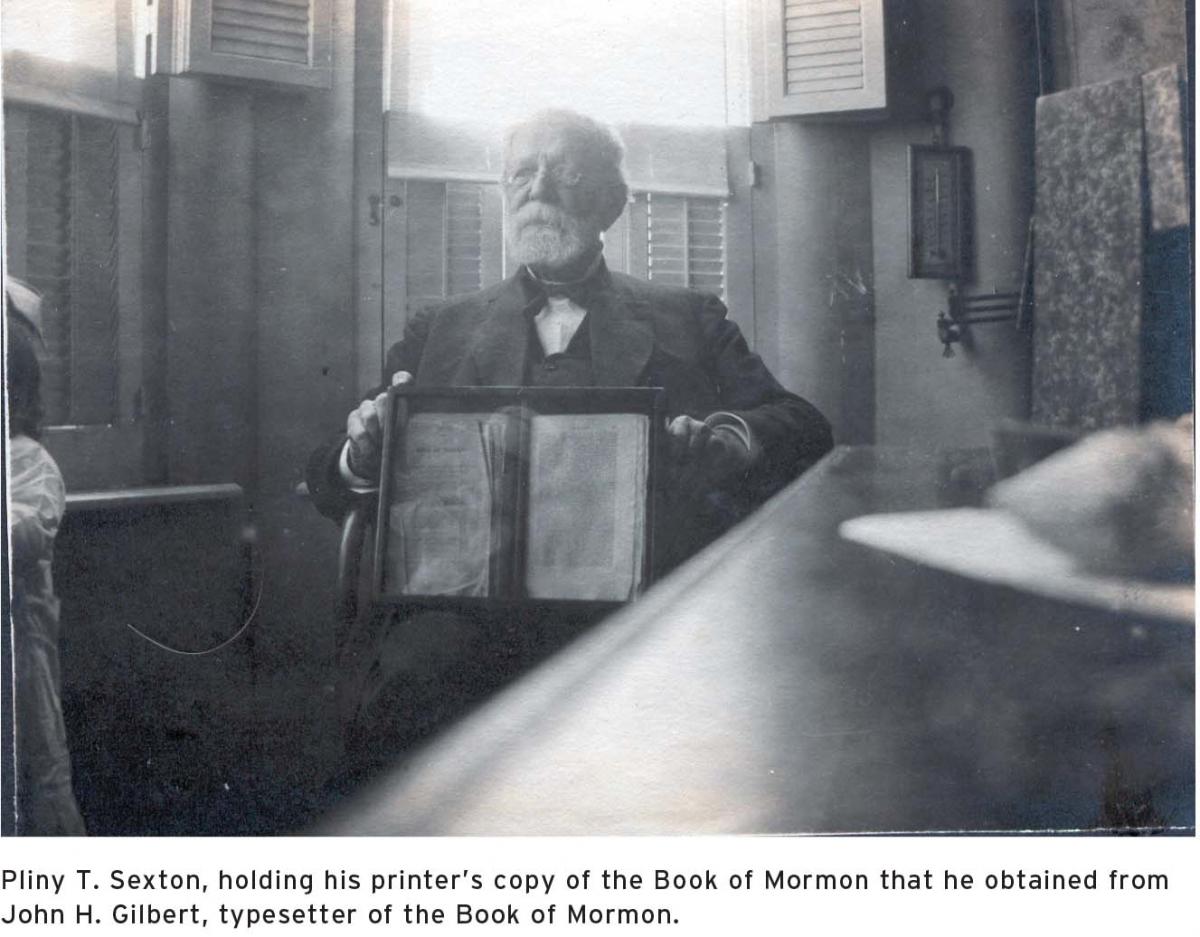

The remainder of the Hill Cumorah was owned by a man named Pliny T. Sexton.A local banker and millionaire, Mr. Sexton owned at least forty-eight properties, including many farms and about one-fourth of all the village property of Palmyra.[37] He also held large portions of land in Kansas and Nebraska.[38] The farm that contained the major portion of the Hill Cumorah (excluding the Inglis property) was deeded to Sexton in 1903 by the widow of Rear Admiral William T. Sampson, who had been in command of the North Atlantic Squadron in the Spanish-American War. Sampson had owned this property since March 13, 1879, when it was deeded to him by the estate of George A. Parker, who died intestate and without descendants. From Parker, the ownership of this portion of the Hill Cumorah traced its way back to Anson Robinson, who received it by will from his father Randall Robinson, who owned the property from 1826 until his death in 1862. Randall Robinson purchased the property from Nathaniel Gorham on April 8, 1826.[39]

After Pliny T. Sexton came into possession of this property, he did what he did with many of his other properties, hiring the Sampson farm (also referred to by some as “Mormon Hill farm”) out to tenant workers. These tenants were usually those who were hostile towards Latter-day Saints who visited the Hill. But after Mr. Sexton became acquainted with Willard Bean, he demanded that his tenants be respectful towards Latter-day Saint visitors to the Hill Cumorah.[40]

Upon becoming friends with Mr. Sexton, Willard Bean did all he could to convert him to the restored gospel. Although he never joined the Church, Mr. Sexton was impressed with Bean’s religion and even commented that he had never heard such a clear interpretation of the scriptures as that which Willard Bean would give in his street meetings outside Sexton’s window.[41] Mr. Sexton also became acquainted with some of the Church’s leaders. When General Authorities would visit the Joseph Smith farm, Willard Bean would take the opportunity to introduce them to the owner of the Hill Cumorah. During one such visit,[42] the Church made its first attempt to buy the rest of the Hill. President Heber J. Grant, Presiding Bishop Charles W. Nibley, and his son Preston Nibley, accompanied by Willard Bean, visited the aging Pliny Sexton at his bank office. After an enjoyable visit, Bishop Nibley ventured to obtain the Hill Cumorah by saying, “Mr. Sexton—this has been a most pleasant visit. We have enjoyed it immensely and now in order to make a perfect day of it, let me phone up the morning newspaper in Rochester and have them send a photographer over with a movie camera and have you go down in history by having you photographed on top of Cumorah Hill in the act of handing the deed to that historic property, to Heber J. Grant, president of the Mormon Church.”[43] While Pliny Sexton was considered a kindhearted and generous man, he was also known to be “cold blooded in business deals” and replied, “Well, I am ready and willing provided I get the proper monetary consideration.”[44] Following this response, the visit quickly came to an end, but while returning to the Smith homestead, Bishop Nibley told Willard, “When the Lord wants us to get possession of that hill, the way will be opened up.”[45]

Another opportunity to obtain the hill came in 1919. Willard Bean reported that Mr. Sexton, at the end of World War I, was having trouble finding suitable tenants to

work some of his properties.[46] Knowing that the Church was interested in the Hill Cumorah property, he called Willard Bean and requested a visit. When Willard arrived at his office, Mr. Sexton stated that due to his tenant dilemma, it might be a good time for him to sell the hill to the Church. When Willard asked him what price he was asking, Mr. Sexton responded, “Right at the present time I believe I could handle $100,000 with less trouble than the hill property.” This exorbitant price shocked Willard, and he jokingly asked if Mr. Sexton had been out to hear the latest anti-Mormon speaker, Mrs. Shepherd, talk about the tremendous wealth of the Mormon Church. Mr. Sexton denied this but said “a piece of property connected with the early rise of a Church as that is with yours should be worth a king’s ransom.” Willard then explained that “the Church had gone along now nearly a hundred years without any noticeable suffering and could probably go on indefinitely without possessing the hill.” Willard did, however, promise to inform the Presiding Bishopric regarding Mr. Sexton’s offer, which he did, and was promptly supported in his rejection at that price.[47]

Although disappointed in not being able to obtain the Hill Cumorah, Willard Bean maintained a good relationship with Mr. Sexton. It seems at one point that Willard thought Mr. Sexton might make a change in his will that would turn the Hill Cumorah over to the Church upon his death, but no change was made.[48] More time passed, and on September 5, 1924, Pliny T. Sexton passed away without selling any of his property to the Church.[49] Local newspapers heralded Sexton as the “perfect billionaire,” and although the Church had refused to buy Sexton’s property at the unwarranted price he asked, these same papers all mentioned how the “Mormon billions” could not persuade him to part with his property, as if the Church had offered a blank check to him.[50]

A few weeks after Sexton’s passing, Bean received a letter from Presiding Bishop Charles W. Nibley. It requested that Willard keep the Church leaders informed in respect to any developments regarding the Hill Cumorah but to not appear too anxious about obtaining it. Bishop Nibley further stated: “If we use caution and the Lord wants us to have possession of the hill, it will be so overruled. Or, on the other hand, no matter how anxious and how hard we may try, unless the matter is overruled in our favor, we will not succeed.”[51]

An article in the Deseret News at the time of Mr. Sexton’s death implied that while Sexton would not sell to the Church, maybe some of his heirs would.[52] Ironically, some of Sexton’s heirs would prove to be a bigger obstacle than he was. Mr. Sexton’s nearest of kin was a niece, who had married a German count named Hans Giese, and an adopted niece, Mrs. Ray. These two ladies, according to Willard, “rounded up other prejudiced heirs and formed a little group who pledged themselves not to sell the ‘Mormon Hill,’ as it was familiarly known, to the Mormon Church at any price.” Part of their reason for their prejudice, and therefore refusal to sell the remainder of the Hill Cumorah to the Church, was that the Church had refused to pay the exorbitant price of $100,000 the first time Mr. Sexton had offered to sell it.[53] Therefore, whenever these heirs or their representatives would meet at the county seat in Lyons, New York, they would register a protest against selling the hill to the Church, which legally blocked the Church being able to buy it.[54] On top of this, these heirs put a staunch anti-Mormon as the tenant farmer on the farm that included the significant remaining portion of the Hill Cumorah. These tenants once again began driving Latter-day Saint visitors off the hill. Willard Bean told the Presiding Bishopric how he responded to this situation:

They ordered our people off a time or two, but when I threatened to post a big sign on our land by the state road where the little lane leads up to his house, warning all Mormons to keep off the hill by order of Frank Burgiss lessee, he began to change his attitude. I would have had it photographed for the local correspondent of a Rochester daily, who is friendly, which would have given him a little publicity he wouldnt [sic] relish. . . . The executors sent their foreman out yesterday to talk with him, which was probably unnecessary as he has been [on] very good behaviour since my little talk with him.[55]

At this point, it appeared that the Church would not be able to acquire the remaining portion of the hill anytime soon due to a few of the heirs who were decidedly against selling to the Latter-day Saints. This course of events may have continued for some time were it not for a key player named C. C. Congdon. Mr. Congdon was the lawyer of the Pliny T. Sexton estate, with whom Willard Bean had just happened to become good friends since moving to Palmyra. Congdon was somewhat upset that Mr. Sexton had not simply willed the Hill Cumorah over to the Church before his death, and although loyal to his charge as the Sexton estate lawyer, he kept Willard informed regarding the heirs’ plans. Although not a member of the Church, Mr. Congdon would ultimately prove to be a major factor in the Church being able to purchase the Hill Cumorah.[56]

By 1925, despite the portion of heirs opposed to the Church, one half of the Sexton heirs had settled on asking the Latter-day Saints to pay $50,000 for the Sampson farm, which included the north and most of the eastern portion of the Hill Cumorah, or $75,000 for this and other surrounding farms.[57] The Sampson farm was worth $13,000 to $14,000 dollars as a farm, and Willard Bean felt that the Church might consider paying up to $20,000 for it in light of the sentimental value it held, but $50,000 was far beyond reasonable.[58] Even if the Church had been willing to pay this exorbitant price for the hill, they would not have succeeded, because the anti-Mormon contingent of heirs continued to register protests against selling to the Church.[59] As time passed, however, the diehard members of the opposition bloc began to pass away. In January 1925 the cashier, Mr. Smith, who had worked for Sexton for fifty years, passed away.[60] Although he was only paid $50.00 a month and had only received one small raise during that time, he had sided with the Sexton heirs opposing the sale of the hill to the Mormons.[61] Coincidentally, in this same year, the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints made an appearance in Palmyra and expressed interest in purchasing the Sexton portion of Cumorah. An Elder Landes, along with two others from their church, made an inquiry and said they would send an offer on the hill.[62]

Mrs. Lucy A. S. Giese was the next heir to pass away who was strongly opposed to selling the Hill Cumorah to the Church. In 1924 she experienced health problems and decided to go to Europe with her husband in order to visit his parents and hopefully aid in her recovery.[63] However in 1927 she returned to Palmyra in a wheelchair and died shortly thereafter.[64]

By 1927 the heirs that were willing to sell to the Church were still stuck on the $50,000 price tag they had originally assigned to the Sampson farm. But in January 1927, C. C. Congdon thought that the heirs might go as low as $35,000 for the Sampson farm as long as they were getting $50,000 for the entire purchase. So he packaged a deal including additional farms bordering Cumorah that would bring the entire package to around $50,000. On August 11, 1927, Willard Bean wrote a letter to President Heber J. Grant outlining this proposal. It presented the offer of the Sampson farm for $35,000 plus some surrounding property for a total of $48,000.[65]

Therefore in 1927 it looked as if the Church might be able to obtain the rest of the Hill Cumorah at close to market value with the additional property averaged into the deal. However in December 1927 the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints made another appearance. In a letter to the Presiding Bishopric, Bean said that President Frederick M. Smith (of the RLDS Church) made a visit to the executors of the Sexton estate and intimated that he would talk to some of their rich members about making an offer for the hill. This naturally excited the heirs who, according to Bean, got the idea that they could “pit one church against the other” and turn it into a bidding war for the hill property.[66] This turned out to be a false alarm, however, and it was not long before the Sexton heirs realized that their best chance for getting any money for the property was still The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. A few months later would prove to be the ideal time for the Church to secure the remaining significant portion of the Hill Cumorah.

On January 30, 1928, Mr. C. C. Congdon telephoned Willard Bean and requested him to come to his office. Willard told him that he would be over as soon as he had eaten his lunch, but Congdon replied that he wanted to talk with him while nobody was around, including his secretary. Willard promptly went over and Mr. Congdon informed him that he had just returned from Lyons where the heirs had met but that because Mrs. Ray, the foremost remaining anti-Mormon heir, was sick, nobody had remembered to register a protest.[67] He had also just met with the surrogate judge and told him that there were three bids for the Hill Cumorah (Sampson farm): one for $25,000 by a local company, one by a California man for $30,000 who felt he could sell it to the Church for $35,000, and the Church’s bid of $35,000. The judge told him that if he could complete the deal with the Church before any protest could be filed, the deal would be legally binding.[68] Congdon went on to tell Willard: “Now you know, and I know that the proper thing would have been for the old gentleman, Sexton, to have willed that hill to the Mormon Church. But he didn’t. You are the only people who can use that hill and by right ought to have it. Now its [sic] up to us to fix this deal up so they can get what they demand and at the same time arrange so you people can get the worth of your money.”[69]

In order to reach the $50,000 mark expected by the heirs, some additional property surrounding the Hill was added to the deal. The Bennett farm, consisting of 220 acres and bordering the Hill Cumorah on the southeast side, was valued at $10,000. A smaller but unproductive ninety-seven acre farm known as the Tripp farm bordered the Sampson farm on the east and was valued at $2,000. These two farms, together with the Hill proper at $35,000, only brought the total to $47,000. Willard then suggested that the heirs had a “white elephant” on their hands in the form of a red brick building known as the Grange Hall.[70] Although it had cost $27,000 when it was first built in 1911, the heirs were not able to sell it. Willard offered $6,000 for it, bringing the total to $53,000. Mr. Congdon thought it was a deal that he could get by the heirs and succeeded in obtaining the needed signatures. He did not, however, require Willard Bean to sign a forfeit on the sale, because he was afraid that it might become public and threaten the deal.[71]

It is interesting to note that while events in obtaining the hill were developing rapidly in New York, Church leaders in Salt Lake City were right in step without actually having conversed with Willard Bean. On February 2, 1928, Willard wrote up the proposal for the purchase of the hill and surrounding properties and airmailed it to the First Presidency, asking them to let him know “at their earliest convenience.”[72] Two days later Willard received a telegram from the First Presidency that said, “See lawyer of Sexton estate and get definite offer for Hill Cumorah alone if possible; if not, with adjacent properties, put it in writing, put up forfeit, and let us hear from you at earliest convenience.”[73] This telegram was dated the same day that Willard had written and sent his letter to the First Presidency. Two days after receiving this telegram, Willard received another from the First Presidency that said, “Terms satisfactory. Close deal.”[74] It is therefore evident that the First Presidency was well aware that the time had come for the Church to purchase the Hill Cumorah, a point acknowledged by the First Presidency in a letter they sent to Willard Bean that said, “We were very glad to learn that you had secured an option on the Hill Cumorah Farm and other property before receiving word from us to do so. We had already noticed the singular coincidence of your writing to us the very same day and possibly the same hour that we were writing to you.”[75] Also of interest is the timing of this purchase in relation to the 1930 centennial of the organization of the Church. With this purchase the Church would have not only the Joseph Smith Sr. farm and Sacred Grove but the Hill Cumorah as well—all sites where significant events occurred prior to the Church’s organization.

The Church closed the deal with the Sexton heirs and thus came into possession of 482 acres of land, in addition to the 97.5 acres they already owned, which included almost all of the Hill Cumorah and much of the surrounding land. By 1929 the Church had sold the Tripp farm on the east side of the hill, which did not border the Hill Cumorah or have any historical significance, for the price they paid for it, bringing the total acreage of Hill Cumorah property to 487 acres.[76]

Reaction to the Purchase

Between the time the Beans moved to Palmyra and the time the Church purchased the rest of the Hill Cumorah, the local sentiment had already changed dramatically. The Beans’ good nature, industry, and determination had won them many friends in the area. Therefore, aside from the hostile Sexton heirs (most of whom had died) and a few others, it seems that many of the local Palmyra residents viewed the Church’s acquisition of the Hill Cumorah favorably.[77]

However, some people farther away from Palmyra who were not acquainted with the Beans used the purchase of the Hill Cumorah as another excuse to attack the Church. A Detroit newspaper, for example, printed an article stained with anti-Mormon rhetoric by a man named Jackson D. Haag. The article begins with a short paragraph explaining that the Mormon Church had just purchased the Hill Cumorah and then spends the rest of a full page casting Joseph Smith and his family in a negative light. While the author claimed he did not know what the Church was planning to do with the Hill Cumorah, he flippantly asserted that the Church would make a “shrine” out of it.[78] Although he used this term pejoratively, he waxed somewhat prophetic in that one day millions would view it as a sacred place. Although these attacks existed, they seem relatively few, and the Church took over ownership without any noticeable public relations problems.

In Utah the Saints were kept up-to-date regarding the purchase of the Hill Cumorah via the Deseret News, which printed articles documenting basic events of the purchase.[79] Naturally, there was great excitement among the Saints at having acquired this piece of property that was so prominent in our history.[80] In the April 1928 general conference of the Church, President Heber J. Grant officially announced the purchase of the rest of the Hill Cumorah as follows: “Within a short time the Church has purchased the Hill Cumorah. The purchase embraces the farm where the hill stands, and the adjoining farm, which together with one that we had already purchased, including part of the hill, gives us now the entire possession of the Hill Cumorah. I know that the hearts of the latter-day Saints thrilled with pride when the announcement was made that we had secured this property.”[81]

Following this announcement, President Anthony W. Ivins of the First Presidency dedicated his entire address to the topic of the Hill Cumorah. This talk seems to have been a directive to the Latter-day Saints on how they should view the Hill Cumorah and its purchase by the Church. President Ivins wasted no time in stating the magnitude of the hill’s purchase:

The purchase of this hill, which President Grant has announced, is an event of more than ordinary importance to the membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The memories of the remote past which cluster round this sacred spot, its close association with the opening of the present gospel dispensation, which has resulted in bringing together this congregation of people, for without it this tabernacle would not have been erected, nor would we have been gathered here in worship today, and the thought which we entertain of the possibilities which its bosom may unfold, make the acquisition of this hill almost an epochal accomplishment in the history of the Church.[82]

President Ivins then spent the majority of his talk attempting to establish what he termed as “facts” regarding the geography of the Hill Cumorah. It appears that President Ivins was attempting to refocus Latter-day Saints on what had been previously taught about the Hill Cumorah by many of the prophets and apostles. Referring to a talk by Elder B. H. Roberts, President Ivins proclaimed that the Hill Cumorah and the hill Ramah are identical and that both Jaredites and Nephites had their last great struggle around this hill. He reiterated that Mormon deposited all the records from Ammaron in this hill except for the abridgment from the plates of Nephi. He then reminded the members that Moroni deposited Mormon’s abridgment and his own abridgment of the Jaredite record in this hill, and testified that it was from this hill that Joseph Smith obtained possession of these plates. President Ivins also reaffirmed what previous leaders of the Church had taught about additional records being deposited in the Hill Cumorah, stating that they “still lie in their repository, awaiting the time when the Lord shall see fit to bring them forth, that they may be published to the world.” However, he also quickly stated that “whether they have been removed from the spot where Mormon deposited them we cannot tell, but this we know, that they are safe under the guardianship of the Lord, and will be brought forth at the proper time.” Interestingly, President Ivins seemed to place particular emphasis on the future role he felt the Hill Cumorah would play in bringing forth records:

All of these incidents to which I have referred, . . . are very closely associated with this particular spot in the state of New York. Therefore, I feel . . . that the acquisition of that spot of ground is more than an incident in the history of the Church; it is an epoch—an epoch which in my opinion is fraught with that which may become of greater interest to the Latter-day Saints than that which has already occurred. We know that all of these records, all the sacred records of the Nephite people, were deposited by Mormon in that hill. That incident alone is sufficient to make it the sacred and hallowed spot that it is to us.[83]

President Ivins concluded his talk by stating that the way the Church had come into possession of the hill “seems to have been providential.”[84] Thus, the reaction of at least one Church leader was exuberance over the fact that the Church had obtained a property that was significant not only because of its past but possibly because of its future.

Conclusion

While some local citizens living in the vicinity of the hill where Mormonism got its start may have hoped that Mormonism would completely fade away, this new religious society took just the opposite course. In the West the Church increased in numbers, strength, and prosperity, and with the passage of years a grateful membership began to look back towards the birthplace of their religion in hopes of purchasing their precious homelands.[85] Because of the many wonderful events associated with the Hill Cumorah, its acquisition by the Church was an exciting accomplishment made possible by the intervention of Deity. Just as W. W. Phelps envisioned, the Hill Cumorah truly does stand as a monument of marvelous works and wonders, even in the story of its reclamation by the Church.

Notes

[1] William Wine Phelps, Latter-day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate 2, no. 14 (November 1835): 221.

[2] Klaus D. Gurgel, “Mormons in Canada and Religious Travel Patterns to the Mormon Culture Hearth” (PhD diss., Syracuse University, 1975). “Mormon culture hearth” is the term Gurgel assigned to the Palmyra-Manchester, New York, region, where many of the events significant to the rise of the Latter-day Saint Church transpired.

[3] President Anthony W. Ivins, in the April 1928 General Conference of the Church, said that the purchase of the Hill Cumorah “seems to have been providential.” See Anthony W. Ivins, in Conference Report, April 1928, 15.

[4] “Hill Where Book of Mormon Plates Rested Is Held in Sacred Memory,” Deseret News, August 20, 1932.

[5] James A. Little, “Reminiscences of Cumorah,” Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Church Archives; hereafter cited as Journal History, April 21, 1876, 3.

[6] “Report of Elders Orson Pratt and Joseph F. Smith,” Journal History, September 27, 1878, 7.

[7] Susa Young Gates, “A Visit to the Hill Cumorah,” Young Woman’s Journal 12, January (1901), 21–22.

[8] Deseret News, January 6, 1906; see Journal History, January 6, 1906, 8–9.

[9] A circa 1910 article with the headline “Mormon Pilgrimage to Gold Bible Hill: Two Hundred Believers in Church of Latter Day Saints Visit Birthplace of Faith in Town of Manchester,” found in King’s Daughter’s Free Library, Palmyra, New York, file marked “Churches L.D.S. (Mormon) Hill Cumorah.”

[10] 1911 articles with headline, “250 Utah Mormons Invade Palmyra,” “Huge Mormon Choir making First Invasion of the Eastern State,” and “Palmyra Awaits Mormon Visit,” found in King’s Daughter’s Free Library, Palmyra, New York, file marked “Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) or (Mormon) History—’Pro’—views and opinions.”

[11] While the local newspapers report a hospitable reception of these early Latter-day Saint pilgrimages, there are records of some Church members being rudely treated, as in the case of Susa Young Gates. See Gates, “A Visit to the Hill Cumorah,” 21–22. The larger groups may have been seen as bringing in some business to the area and therefore treated better. Such seems to be implied by one article that stated how the town members and businesses went to great lengths to court the patronage of a two-hundred-person party of Saints; November 1, 1911, newspaper article entitled, “Mormon Pilgrims Visit Home of Prophet who found ‘Golden Plates,’” located in the King’s Daughter’s Free Library, file marked, “Church of Jesus Christ Historical Sites (LDS).” In spite of this, President Joseph F. Smith still commented that Palmyra, New York, was one of the most prejudiced places in the world. See Willard Washington Bean, Autobiography of Willard Washington Bean, Palmyra Bean Packer Collection, Provo Utah, 2:24.

[12] Willard Bean was the permanent presence of the Church in Palmyra from 1915 to 1939. While he was there, Mormon pilgrimages to the hill continued. Since Bean was there, he took on the responsibility of showing the visitors around the farm and hill. One example of this is a letter from Joseph F. Smith to Willard Bean requesting Bean to show his daughters the Hill Cumorah and Sacred Grove. (Joseph F. Smith, July 16, 1916, Palmyra Bean Packer Collection, Provo, Utah.)

[13] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, April 1907, 7.

[14] Bean, Autobiography, 2:24.

[15] Although the purchase of the Joseph Smith farm did not include the Hill Cumorah, Eastern newspapers reported that it did. They also reported that the Mormon Church was planning on putting a tabernacle on top of it; see the Deseret News, June 12, 1907, as found in Journal History, June 11, 1907, 2. Two informative works on this era of the Hill Cumorah are Rex C. Reeve and Richard O. Cowan’s article entitled “The Hill Called Cumorah,” Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: New York (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 71–91; and Rand Hugh Packer, “History of Four Mormon Landmarks in Western New York: the Joseph Smith Farm, Hill Cumorah, the Martin Harris Farm, and the Peter Whitmer Sr. Farm” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1975).

[16] Gates, “A Visit to the Hill Cumorah,” 21–22.

[17] Rebecca P. Bean, “An Account of the Palmyra Missionary Experiences of Willard W. Bean and Rebecca P. Bean, 1964,” Palmyra Bean Packer Collection, Provo, Utah, 1–2.

[18] Bean, “Account of the Palmyra Missionary Experiences,” 2.

[19] Bean, Autobiography, 1:24–5.

[20] Bean, Autobiography, 2:24.

[21] Bean, “Account of the Palmyra Missionary Experiences,” 2.

[22] Rand H. Packer, “History of Four Mormon Landmarks,” 25.

[23] Willard Bean had two children from a previous marriage, Paul and Phyllis, who went to Palmyra with Willard and Rebecca.

[24] Bean, Autobiography, 2:31, italics added. The transfer of the farm referred to in this quote is the fact that the farm was bought by George Albert Smith as a private party and not by the Church. Willard had been directed not to be too hasty in transferring the title to the Church, but the negative treatment they received hastened the transfer, according to Bean.

[25] Bean, “Account of the Palmyra Missionary Experiences,” 5.

[26] Bean, Autobiography, 2:31; 3:100. See Appendix, 3:157, for a sketch of Inglis farm.

[27] Bean, Autobiography, 2:31–32.

[28] Willard W. Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, June 19, 1923, General Office Files, Presiding Bishopric, Church Archives. All letters from Willard W. Bean to the Presiding Bishopric were obtained from this source unless otherwise specified. Apparently another reason why Bean was so motivated to acquire a portion of the Hill Cumorah was that members of the RLDS Church were making advances on another owner of the Hill Cumorah property, Pliny T. Sexton, with regards to purchasing his lands, one of which included a major portion of the Hill Cumorah. Willard said that six carloads of members of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints had visited two weeks previously; see Willard W. Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, September 15, 1923, Church Archives.

[29] Willard W. Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, July 31, 1923, Church Archives.

[30] Willard W. Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, July 31, 1923, Church Archives.

[31] The Inglis farm was valued at $11,000 and the equipment and livestock at $3,000, making the purchase what B. H. Roberts called “a good buy.” Willard W. Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, September 15, 1923, and October 16, 1923.

[32] A copy of this transaction is found in the “Hill Cumorah” file of the Real Estate Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. See also John Davis Giles Collection, reel 5, box 6, folder 12, Church Archives. See also Bean, Autobiography, 2:31–32.

[33] Personal interview with Jeff Reeves, Orem, UT, August 20, 2002.

[34] Willard W. Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, January 14, 1924, Church Archives.

[35] Willard W. Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, January 14, 1924, Church Archives.

[36] Heber J. Grant, in Conference Report, October 1923, 22–23.

[37] Bean, Autobiography, 2:33.

[38] Bean, Autobiography, 3:101.

[39] Information taken from copies of the pertinent land deeds in the writer’s possession, obtained from Ontario County RAIMS, 3051 County Complex Drive, Canandaigua, NY, 14424. See also Journal History, December 21, 1929, 8–10; and the John Davis Giles Collection, reel 5, box 6, folder 12, Church Archives. See also the Historic Sites file, Church History Library, folder labeled “Hill Cumorah.”

[40] Willard W. Bean, “How We Got the Hill Cumorah,” Church News, January 23, 1943, 3.

[41] Bean, Autobiography, 2:34.

[42] The exact date of this particular visit is not known; however, Bean said that it occurred prior to 1919. Bean, “How We Got the Hill Cumorah,” 3.

[43] Bean, Autobiography, 2:33.

[44] Bean, Autobiography, 2:33.

[45] Bean, Autobiography, 2:34.

[46] Bean implied that Sexton had accumulated numerous properties by “buying up and foreclosing mortgages” and simply had too many properties to find tenants for. Bean, Autobiography, 2:32. An unfortunate result of this was that many of his properties fell into disrepair. In 1924 Bean wrote, “Dozens of his [Sexton’s] farms are so badly run down that they will hardly be able to give them away.” See Willard Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, December 1, 1924, Church Archives.

[47] Bean, “How We Got the Hill Cumorah,” 3. For the remainder of his life, Sexton would not budge from his original asking price of $100,000 and even told Bean that if the Church did not purchase it at that price, his hill property would go to the State Historical Society upon his death. Willard W. Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, March 1, 1923, Church Archives.

[48] Bean, Autobiography, 2:34.

[49] Mr. Sexton’s will was made in 1907 and probated on September 13, 1927, at Lyons, New York. One paper reported, “The estate, valued at $2,000,000, one-half of which is represented by real estate and the other half by personal property, is reported to be the largest ever taken before the Wayne county surrogate court for settlement,” Journal History, September 13, 1927, 2.

[50] Miscellaneous articles found in King’s Daughter’s Free Library, Palmyra, New York, family file cabinet, folder marked “Pliny Titus Sexton.”

[51] The Presiding Bishopric to Willard W. Bean, September 23, 1924, in Palmyra Bean Packer Collection, Provo, Utah.

[52] Journal History, September 16, 1924, 6.

[53] Bean, Autobiography, 3:101.

[54] Bean, Autobiography, 2:34.

[55] Willard Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, October 3, 1924. In this letter, Willard also states that Burgiss “is out of harmony with public sentiment which is overwhelmingly in favor of us getting the Hill.”

[56] Bean, Autobiography, 2:34.

[57] Willard Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, January 22, 1925, and Bean, Autobiography, 2:34. Also Willard Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, January 24, 1927. The other farms Bean is referring to are the Bennett and Tripp farms. See Appendix in Bean, Autobiography, 3:158 for sketches of the Cumorah farms.

[58] Willard Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, February 9, 1925.

[59] Bean, Autobiography, 2:34.

[60] Willard Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, January 22, 1925.

[61] Bean, Autobiography, 2:34.

[62] Willard Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, January 22, 1925. The amount of the RLDS offer was not known to Bean.

[63] Willard Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, December 31, 1924.

[64] Bean, Autobiography, 2:32.

[65] Willard Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, January 18, 1927, and August 11, 1927.

[66] Willard Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, December 20, 1927. The RLDS interest in the Hill Cumorah provides good corroborative evidence of the historical importance of the hill.

[67] Bean, Autobiography, 2:34.

[68] Bean, “How We Got the Hill Cumorah,” 6.

[69] Bean, “How We Got the Hill Cumorah,” 6.

[70] The Grange Hall was a building that was appraised at $38,000 at the time of this deal. Mr. Sexton had previously foreclosed a mortgage of $9,500 on it, but Willard was able to get it in the deal for only $6,000; Bean, Autobiography, 2:34.

[71] Bean, “How We Got the Hill Cumorah,” 6. See also Bean, Autobiography, 2:34.

[72] Bean, “How We Got the Hill Cumorah,” 6. See also Willard Bean to the Presiding Bishopric, February 2, 1928.

[73] Bean, Autobiography, 2:35.

[74] Bean, “How We Got the Hill Cumorah,” p. 6.

[75] The First Presidency to Willard W. Bean, March 6, 1928, Palmyra Bean Packer Collection.

[76] Bean, Autobiography, 2:35.

[77] Bean, “How We Got the Hill Cumorah,” 3; also personal interview with Palmyra Bean Packer who was living at the Joseph Smith farm at the time the Church purchased the Hill Cumorah and is now (2002) residing in Provo, Utah.

[78] Jackson D. Haag, The Detroit Michigan Evening News, July 11, 1928; see Journal History, July 14, 1928, 7.

[79] Journal History, February 18, 1928, 2.

[80] Journal History, February 18, 1928, 2.

[81] Heber J. Grant, in Conference Report, April 1928, 3. For all intents and purposes, the Church does own the entire hill; however, technically, the Church’s property ends on the south before the hill actually does. See the map of the current Church property in the Appendix of Bean, Autobiography, 3:159.

[82] Anthony W. Ivins, in Conference Report, June 6, 1928, 10–15, emphasis added. This talk was later reprinted in The Improvement Era 31, no. 8 (June 1928): 675–81.

[83] Ivins, in Conference Report, April 6, 1928, 10–15.

[84] Ivins, in Conference Report, April 6, 1928, 10–15, emphasis added

[85] Richard H. Jackson, “Perception of Sacred Space,” Journal of Cultural Geography 3, no. 2 (1983), 95.