Robert J. Matthews and His Work with the Joseph Smith Translation

Ray L. Huntington and Brian M. Hauglid

Ray L. Huntington and Brian M. Hauglid, “Robert J. Matthews and His Work with the Joseph Smith Translation,” ReligiousEducator 5, no. 2 (2004): 23–47.

Ray L. Huntington was associate department chair of ancient scripture at BYU, and Brian M. Hauglid was an associate professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this was published.

In 1979, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints published its edition of the King James Version of the Bible. The Scriptures Publication Committee decided to include portions of the Joseph Smith Translation in the new edition. For the first time, Latter-day Saints had access to Joseph’s inspired work in their own personal scriptures. Many Latter-day Saints may be unaware that the efforts to include the JST material in the new edition of the Bible were pioneered by Robert J. Matthews, former dean of Religious Education at Brigham Young University. Beginning in 1953, Brother Matthews began a letter-writing campaign to the RLDS Church (now called the Community of Christ), requesting permission to study the original JST manuscripts. Through his sustained efforts, the RLDS Church gave Brother Matthews permission to examine the manuscripts.

We feel there is a great need for Latter-day Saints to hear Brother Matthews’s story, which culminated in the decision of the Scriptures Publication Committee to include excerpts of the JST in our LDS edition of the Bible. As we conducted this interview, it became clear to us that the Lord raised up Robert J. Matthews to do this significant work.

Huntington: Brother Matthews, could you please give a brief historical overview of the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible?

Matthews: The Prophet Joseph Smith began translating the Bible in June of 1830. He worked steadily, with some breaks in between, from June of 1830 to July 1833. So it took just over three years. During that time, he went all the way through the Old Testament and all the way through the New Testament, but not in that order. He began in Genesis 1 and translated through Genesis 24:41, and the Lord told him to begin translating the New Testament (D&C 45:60–62). He then went to Matthew and translated all of the New Testament sequentially and then went back to Genesis and did the rest of the Old Testament. He finished the Old Testament on July 2, 1833.

Joseph Smith began translating in Harmony, Pennsylvania. Then, because of persecution, the Prophet moved to the Whitmer home in Fayette, New York. The second portion of Genesis was done in Fayette. Then, he moved to Kirtland, and because of persecution at Kirtland they moved to Hiram, where most of the New Testament was done between September 12, 1831, and September 12, 1832. After completing the New Testament, he moved back to Kirtland, and it was in the upstairs of the Whitney store that he finally finished the Old Testament. The first scribe was Oliver Cowdery, and he wrote the first ten pages in Genesis, and that is pretty much what we have in the book of Moses, chapters 1 through 5. Then, Oliver was called on a mission, as you know, to the Lamanites in Missouri. John Whitmer became the scribe, and after that Emma was scribe for a little while, and then Sydney Rigdon came on the scene and remained the scribe for quite a long time. He is listed in Doctrine and Covenants 35:20, where the Lord says that Sydney was to write for Joseph. He was writing the JST, but then Sydney became ill after the persecution at Hiram when he was dragged by his heels on the frozen ground. He didn’t write much after that, and Frederick G. Williams became the scribe. They were pretty much through the New Testament at that time, and Frederick G. Williams finished recording changes in the New Testament.

Joseph Smith wrote a little, but not much. It is hard to tell just what parts are his and what are not. His writing contribution is rather small. There is also, in addition to the handwritten manuscript, a large pulpit-sized edition of the King James Version of the Bible, published by H&E Phinney in Cooperstown, New York, in 1828. Oliver Cowdery purchased that Bible for $3.75 from the Grandin Bookstore in Palmyra. Someone—we don’t know whether it was Joseph or Oliver or who, maybe it was all of them—went through portions of it and made little marks, sometimes a check mark in front of a verse and then an indication within the verse where there needed to be a correction.

In the places where they marked the Bible, they just wrote the reference and then the correction in the manuscript—not the entire verse, just the correction; so both the marked Bible and the manuscript had to be used together.

After they moved to Nauvoo, the Prophet went through the manuscript again, editing it and getting it ready for the press, and there is quite a lot of information in the Times and Seasons indicating that they were planning to publish the JST in Nauvoo. That was where it was at the time Joseph was killed. I will make one similarity here. The JST was started in Harmony and then worked on in Fayette; that’s a little like the translation of the Book of Mormon. We talk about part of the Book of Mormon being translated upstairs in the Whitmer home. Well, so was part of the JST. The translations involved the same people, Oliver Cowdery, John Whitmer, Joseph Smith, and so on. So there is a little similarity there.

Hauglid: Brother Matthews, what does the manuscript look like?

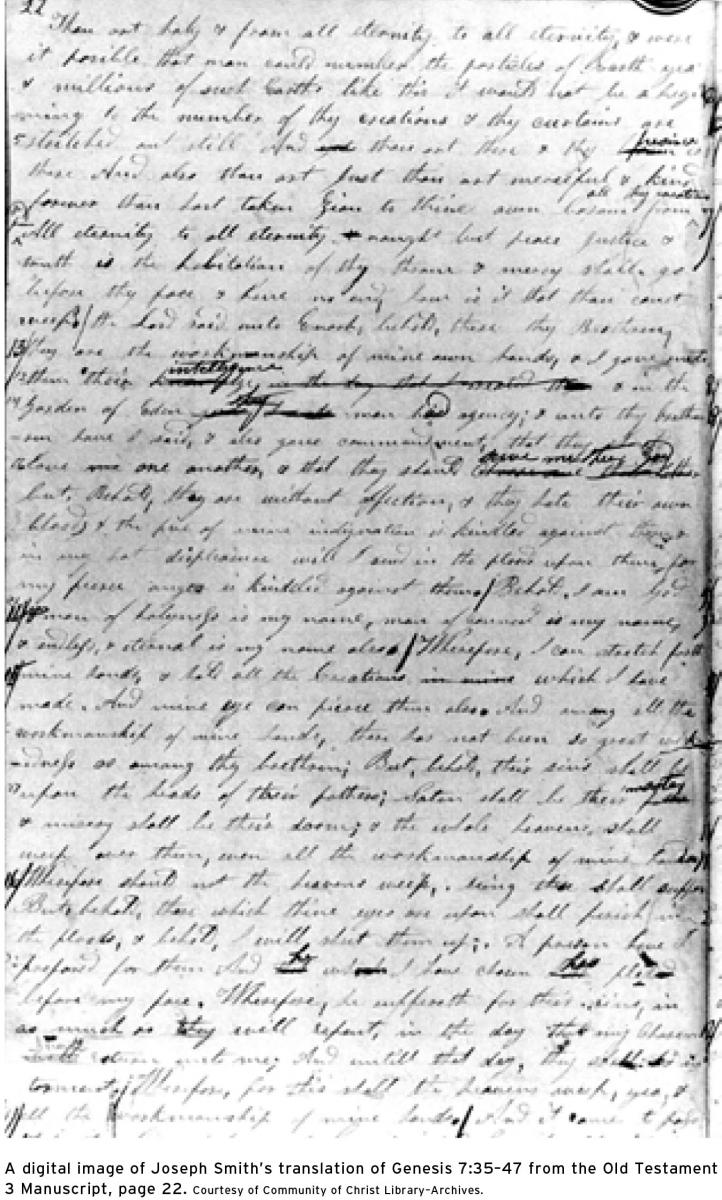

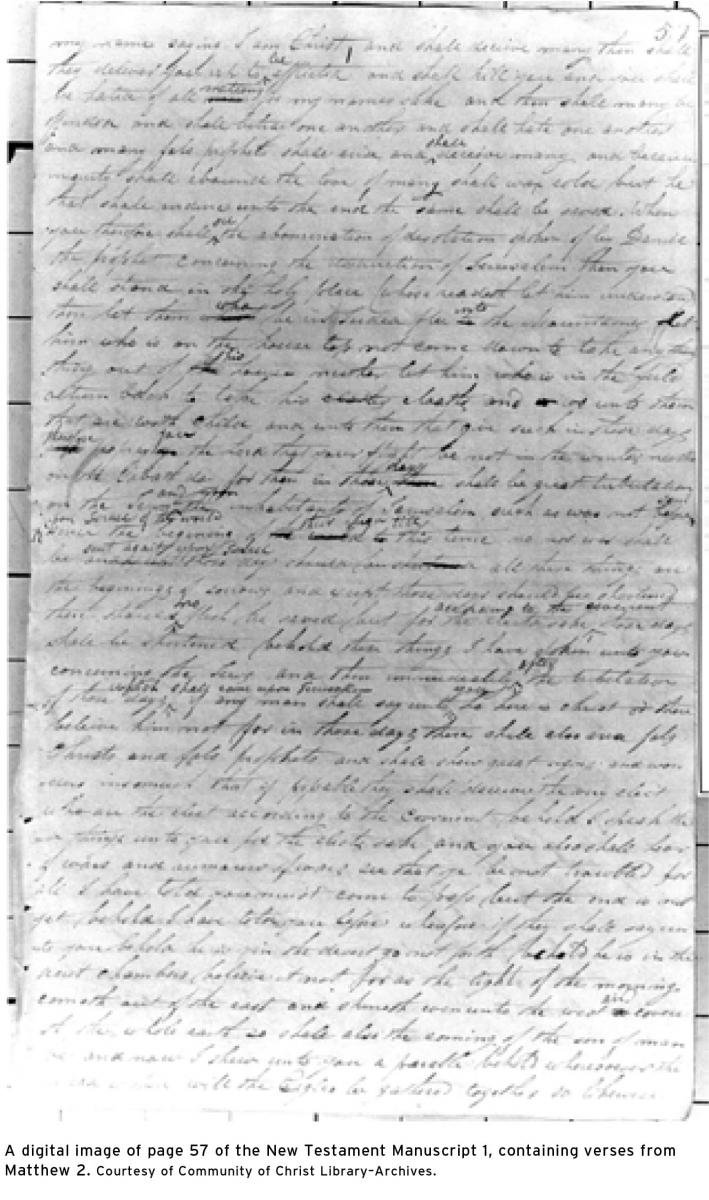

Matthews: The paper is yellowed and has no lines. If it ever did have lines, they are not apparent. The ink, which was no doubt black at the time they were writing, has turned to a rich, dark brown. The pages are really quite attractive. They are kind of a tan paper with dark brown writing. The scribes wrote right out to the edge of the paper. You couldn’t put a pin sometimes between where the writing ends and the edge of the paper. The pages originally were fourteen inches by seventeen inches and then folded to make eight and one-half by fourteen. And they wrote on both sides of the paper.

Hauglid: How many pages?

Matthews: There are about four hundred fifty pages.

Huntington: Were all the corrections Joseph made to the Bible written only in the manuscript?

Matthews: Yes, the Bible doesn’t have any words of correction, just indications where corrections are to be made. They had two ways of translating. When they first started, they wrote the whole chapter in the manuscript, even the passages that didn’t need to be changed. They even wrote entire chapters that didn’t need any correction. That was very slow, so then they adopted a faster method, and that was to mark the Bible where corrections needed to be. Then all they wrote on the paper was the correction. That was much faster.

Huntington: When and where did the RLDS Church first publish the Joseph Smith Translation?

RJM: When the Prophet was killed, the manuscript and the marked Bible were at the Smith home. The RLDS Church was organized on April 6, 1860. In 1866, they decided that they ought to publish the Prophet’s translation of the Bible. So they organized a committee and went to Emma, and the spokesman for the committee was Joseph Smith III. He went to his mother and said, “Can we have the manuscript?” She said yes and gave him the manuscript. The headquarters of the RLDS Church at that time were in Plano, Illinois, and that is where they did the work on it. The Bible translation came off the press in 1867. I think that it was actually printed in Cincinnati. This original edition had no footnotes, cross-references, or anything. Then, in 1936, after a committee labored for several years, the RLDS Church published a teacher’s edition. This edition had a concordance, footnotes, cross-references, and a lot of things. That’s when they first officially called it the Inspired Version. Until then, it was officially called Holy Scriptures. In 1936, the teacher’s edition was called Holy Scriptures, Inspired Version, although many had begun to call it the Inspired Version.

It became evident that there were some typographical errors in the text of the 1867 JST, or Inspired Version, as they called it. So in 1944, the Reorganized Church published A New Corrected Edition. That caused alarm among Mormons in the West, because some thought the Reorganized Church had made new changes. Actually, what they were doing was comparing it to the manuscript and correcting the typos. I have found 342 typos in that first edition. This teacher’s edition was exactly the same text as the 1867 edition, and in 1944 they corrected those. But in doing the corrections, they also made other errors, so they still had to make some more corrections in later editions, and then it was printed frequently off and on. The most recent edition was published in 1991.

Hauglid: Where were the JST manuscripts kept from the death of Joseph to the first publication of the Inspired Version in 1867?

Matthews: Well, interestingly enough, they were not kept in the RLDS Church archives because the Smith family considered them Smith family property. When Brigham Young and the others were leaving Nauvoo to come west, President Young sent Willard Richards to Emma to see if she would give him the manuscript and the Bible, and she said, “No, that’s not Church property. That’s our Smith family Bible, and that’s Smith property.” It was kept in Emma’s house, so that’s where Joseph Smith III went to get it. He went to Emma in the Mansion House in Nauvoo and got the manuscript. Emma’s house caught on fire two or three times, and Emma also lived in various places. She makes mention in a letter (which the Reorganized Church has and which I’ve read) and in writing to her son that the translation is a very precious manuscript. She said, “I really believe that’s why my house never burned down, that the Lord was protecting that manuscript.”

There is another note to add here. After the publication of the Bible, the headquarters of the Reorganized Church were moved to Lamoni, Iowa. In either 1907 or 1909, there was a major fire at Lamoni that burned most of the diaries, almost all of the other manuscripts, and almost all of the rare things at RLDS headquarters. Fortunately, the JST manuscript was at the home of one of the Smiths. So viewing it as Smith property may have saved the manuscript.

Huntington: Did the RLDS publish directly from the original manuscripts prepared by Joseph Smith and his scribes?

Matthews: No, they didn’t. The RLDS did the same thing that was done with the Book of Mormon. That is, the 1866 Publication Committee of the RLDS Church made an entire duplicate of the JST manuscripts. The Reorganized Church still has that. I’ve seen and handled it. It seems to be a good, faithful copy of the original. Every time you do anything by hand, you make a few little variations. So the type was set from the Committee Manuscript, not from the original.

Hauglid: Where have the manuscripts been since the first publication in 1867?

Matthews: They had been kept in a trunk at Emma’s house. She moved from time to time. The trunk had a false bottom. I read in RLDS literature that the manuscripts were kept in this trunk that had a false bottom, so they were totally out of sight. For some reason, they didn’t always keep the Bible with the manuscript. They looked upon the manuscripts as very important and the Bible as more of a keepsake. Joseph’s son, Alexander Hale Smith, was given the Bible. He had that Bible in his library in his home in Lamoni. When his twenty-year-old daughter Elizabeth was married, her father said to her, “Any of my books that I have you’re welcome to as a wedding present.” She said, “I want grandfather’s Bible.” That’s the marked Bible. Alexander let out an “oh.” And she said, “Now you said . . . “ So he gave Elizabeth the marked Bible. After their marriage, her husband wanted to move to San Bernardino, California. That was frontier country, so that Bible traveled out to San Bernardino, probably in a wagon. He was killed there in an accident, and she came back, bringing the Bible with her, and it was later that the manuscript and the Bible were put in the archives of the Reorganized Church. After Alexander Hale Smith died, the Bible was kept by Israel Alexander Smith, another one of the brothers, and the Bible and the manuscript were kept in his home until 1942. Then, the Bible and the manuscript were put in the archives of the Reorganized Church.

Huntington: How did the Bible and the manuscript become the property of the RLDS Church?

Matthews: Inside the cover of the Bible, there are two or three paragraphs telling about this. It doesn’t tell about San Bernardino, but it says on such a date Elizabeth Smith brought back the Bible and gave it to Israel Alexander Smith, and he donated it to the Reorganized Church.

Huntington: In the LDS Church we call the Prophet Joseph Smith’s work with the Bible the Joseph Smith Translation, or JST. My understanding is that it hasn’t always been called this. What have been some of the other names given to Joseph’s translation of the Bible?

Matthews: Well, it’s evident from reading the Doctrines and Covenants and also the History of the Church that the Prophet Joseph always called it the New Translation. Then, when the Reorganized Church published it, they called it Holy Scriptures. Then, in 1936, with the teacher’s edition, they tacked on the subtitle Inspired Version, and that’s the way it was spoken of until the time when the LDS Church was working on the project of a new edition of the King James Version in the 1970s. We wanted to quote from the Prophet’s translation, but when you quote in footnotes, you have to have abbreviations. NT, which would mean New Translation, looks too much like New Testament, especially in a footnote, so it was ruled out. IV looks too much like a Roman numeral IV, so that was also ruled out. It was decided by the committee in the 1970s and presented to the First Presidency and the Twelve to call the Prophet’s work the Joseph Smith Translation, and the proper abbreviation would be JST.

Hauglid: When did you first become interested in the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible?

Matthews: As a boy growing up in Wyoming, I was the last of a large number of children. Our family was active in the Church, but I never heard anybody ever talk about Joseph Smith’s translation of the Bible. I didn’t know he had made one. On July 9, 1944, I had just graduated from high school, and I was sitting in the living room of my father’s home listening to Elder Joseph Fielding Smith give a lecture over KSL radio. He gave a series of lectures. On that day, he was speaking about the Godhead, and he quoted John 1:18, which says, “No man hath seen God at any time.” And then Elder Smith said, Joseph Smith corrected that verse by revelation, and when he said revelation, that word penetrated right into my soul. It was the word revelation that did it. It struck me. It didn’t hurt, but I knew that I’d been hit. Those lectures have since been published in a book called The Restoration of All Things, by Joseph Fielding Smith. That is how I know that experience took place on July 9, 1944, because I looked it up to see what day he had given that radio address. It was a deep feeling within me that Joseph Smith made some corrections in the Bible by revelation. Then, I began to want to know more. That fall I came to BYU as a student and went to Dr. Sidney B. Sperry and asked him if he knew that Joseph Smith translated the Bible, and he said, “Yes, we know, but we don’t know much about it.” So that was the beginning of my interest, and I never lost that feeling. Although months would go by and I’d never do anything about it, I always had a sustained interest in the Joseph Smith Translation. Through the years after that, I obtained a copy of the Inspired Version, published by the RLDS Church.

You know the name of N. B. Lundwall, who published a lot of Church books. I couldn’t find an Inspired Version in any bookstore, so I wrote to him. He said he could get me one. He also told me something I had never known, and that is, he was a convert from the Reorganized Church. He got me my first copy of the Inspired Version, and I read the entire King James Version and Inspired Version, holding them side by side, reading a line from one and reading a line from the other. I went through both Bibles comparing every word. It took me several years, but I eventually did that.

Huntington: When did you do that?

Matthews: I did that between 1945 and 1950. That’s how I became acquainted with all of the changes. I had them marked in my Bible.

Hauglid: Do you still have the Inspired Version that Brother Lundwall got for you?

Matthews: Yes, I still have it. I was so interested in these changes, and I also noticed that they were the same as the book of Moses. So I would talk to people in my ward about these corrections Joseph Smith made. Everybody would say, “Oh, you can’t trust that. That’s the Reorganized Church. We don’t believe in that.” That’s the thing I heard most of all. “We don’t believe in that.” Everybody had the same thought: “It’s been changed by the Reorganized Church.” So I could see that if I was ever going to know what’s right and what’s wrong, I had to see the original manuscripts.

Huntington: Could you describe the events leading up to your initial contact with the RLDS Church?

Matthews: I remember talking to Dr. Sperry and Dr. James R. Clark about it. Brother Clark was the expert in the Church, or the expert at BYU, on the Pearl of Great Price. I remember asking him, “Is the book of Moses part of Joseph Smith’s translation of the Bible?” I don’t say this to discredit him, because nobody knew. He said, “I don’t know.” I said, “Well, it reads just like the beginning of the RLDS publication.” He said, “Well, it could be, but we don’t know.” So in talking with Dr. Sperry and Dr. Clark, I realized that if I was ever going to get any truth about this thing, I had to see the original manuscripts.

Huntington: Were you a teacher at BYU?

Matthews: No, I was a student. Along the way, in 1955, I became a seminary teacher. I wrote a letter to the Reorganized Church to ask them if I could see the manuscript. They wrote back and said no.

Hauglid: When was that, Brother Matthews?

Matthews: Well, it took fifteen years, so it was back in 1953 when I first wrote to them.

Huntington: How often did you write to the RLDS Church requesting to see the manuscripts?

Matthews: Off and on. I didn’t write every week, but over a period of fifteen years I kept writing, and they kept writing back and saying no. I wrote to their historian. He said no. I wrote to the president of their church two or three times. I may have been a little too strong at one point. I said to him in one letter, “I’m not trying to deceive or trick anybody. You’re just a little church, and we’re a big church and if you really have confidence in your grandfather’s work” (he was the grandson of Joseph Smith), “if you really have confidence in your grandfather’s work, our people are never going to accept it until somebody from our church has seen the manuscript.” He wrote back and said, “I thank you for your plainness, but the answer is still no.” Then, I read in the Deseret News that their church historian had died and that the new historian was Richard Howard. He was a graduate of Berkeley in history. So I wrote him a letter and said, “If I came to Independence, would you show me the manuscript?” And he wrote back and said yes. I thought he didn’t understand, so I called him on the phone. He said, “Yes, yes. You can come.” That’s how I finally got to see the manuscript.

Hauglid: Who were your contact people at the RLDS Church?

Matthews: Well, I originally contacted their historian, whose name was Charles Davies, and he said no two or three times. I tried their president, who was W. Wallace Smith, and he said no two or three times. So the first real flesh-and-blood contact that I had was Richard P. Howard, who was a gentleman and a fine man and a good scholar. The first time I went there, he showed me the marked Bible.

Huntington: What year was your first visit to see the marked Bible?

Matthews: This was on June 20, 1968. The reason I was able to do that was that I was on a three-week lecture tour for BYU, and my last lecture was June 20, in Kansas City. That’s just seventeen miles from Independence. He brought out the marked Bible and showed me a photocopy of the manuscript—not the original but a photocopy. I said, “Well, this is really nice, but any chance to see the original?” He said, “No, that’s too precious.” I said, “Well, can I look at this?”

“Yes, you can look at it.” So I would read and read from the photocopy, and every once in a while I would find words that were crossed out and something written above it. Now, on a photocopy, everything was black and white. So I went to Richard Howard and said, “Richard, I need to look at the original manuscript to see whether the ink in the cross out and the new words written above are the same color as the rest of it.” He agreed. So he would get that original page of the manuscript, and I would look at it. So little by little, I began to have access to the manuscript. Then, after I’d been there a couple of trips, he would get the original manuscript and I would work straight from that. But it was a gradual thing.

Hauglid: How many visits did you make to the RLDS archives? What took place in those visits?

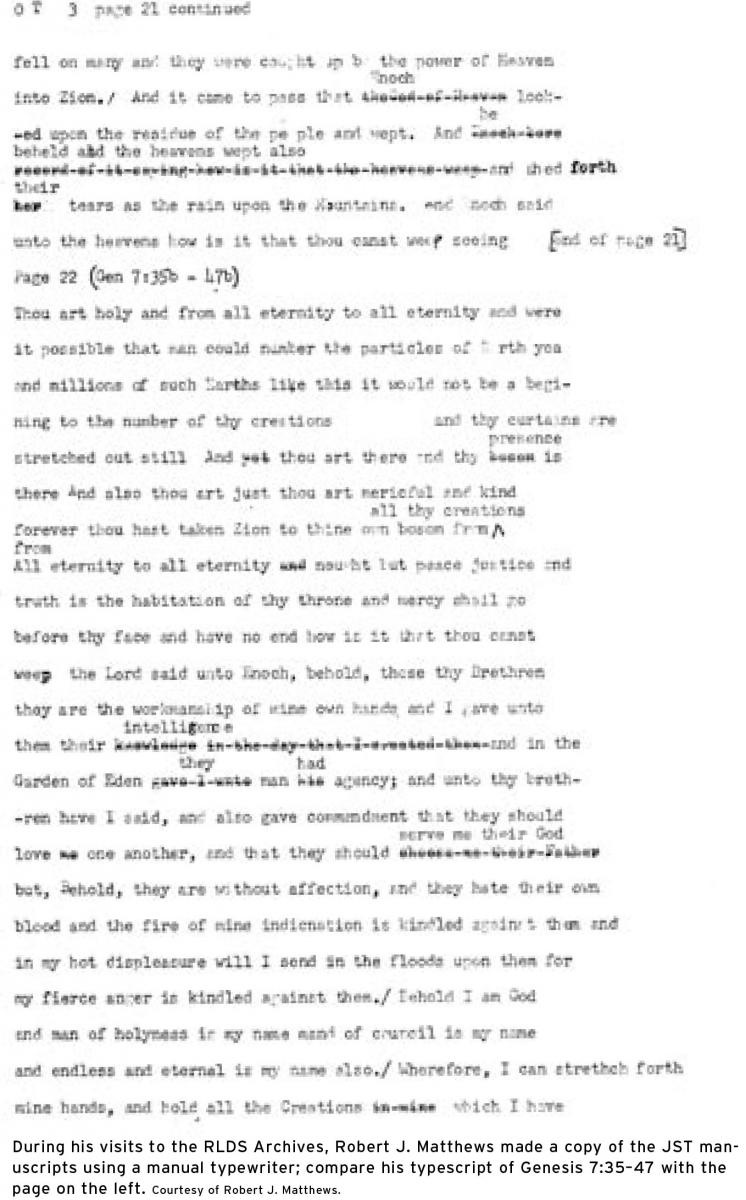

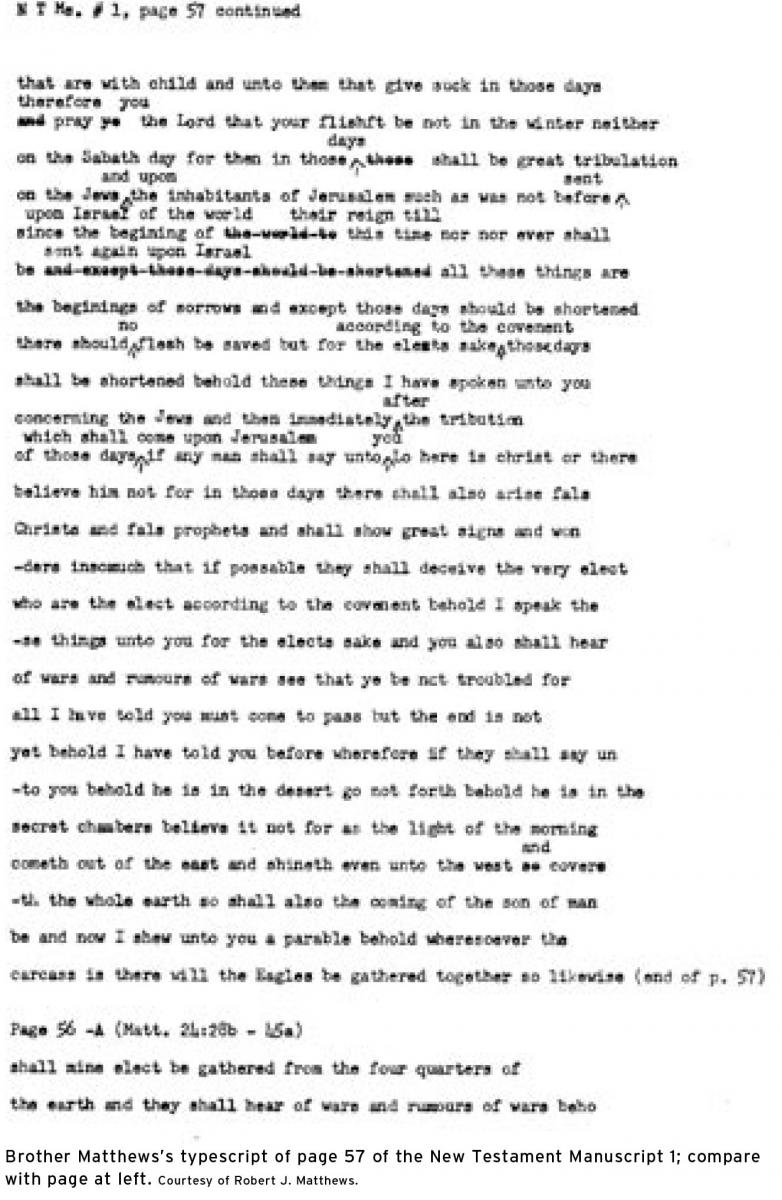

Matthews: Altogether, it took thirteen visits from 1968 to 1974, and except for the first one, which was only one day, I stayed a week for each of the other twelve visits. I would get there on Monday, be at their office when they opened at eight in the morning, stay all day until they closed at night, and stay a week. They were not open on Saturdays, so I would be there Monday through Friday. Sometimes I would go a whole year or several months in between without a visit. I copied all the marks that were in the marked Bible that we’ve talked about. I went to their bookstore downtown and bought a King James Version of the Bible. Then, with the large, marked Bible of Joseph Smith, I copied every mark from that Bible into my King James Version. I didn’t count how many, but I kept track of the time. It took seventeen hours of diligent marking to copy every cross out, every check mark, every circle, and every item.

There is one interesting thing about Joseph Smith’s Bible. It does not contain any of the words of the correction, but frequently in the margin he would write, “This is my book” and sign “Joseph Smith.” Across the top of the page he’d write, “Joseph Smith Jr.” Once he wrote in the margin, “O Lord, bless Oliver.” So there were little things like that. It authenticates the book. I copied all of those.

Hauglid: Do you still have your copied Bible?

Matthews: Oh yes. I’ve also copied the changes into five other Bibles since then. Another thing I did, having read the entire printed JST, was to compare it to the King James before I ever made any of these visits. I had certain questions, and so I would turn and find the original for each of those statements. Then, after I got all of that satisfied, they let me use their typewriter and they provided the paper, and I typed the entire manuscript, line by line—in other words, a line of writing in the manuscript made one line of typing. So I have a complete copy, line for line of the original JST manuscript.[1]

Huntington: All four hundred and something pages?

Matthews: Yes. There are two Old Testament manuscripts, and there is a set of New Testament manuscripts. It works like this. The first draft is not punctuated or versed. The second draft is revised in words, plus you can tell it is being prepared for a printer because it often has versification, chapter headings, and so on. So there are two Old Testament and two New Testament manuscripts. Then, they had an additional Old Testament manuscript, just a few pages. It went through about seven chapters of Genesis, which they thought to be the first draft, but it has since been decided that that little short manuscript was probably John Whitmer’s own personal copy.

Huntington: How did your interest and research with the JST manuscripts contribute to the LDS publication of the King James Bible in 1979?

Matthews: When I was doing this work with the Reorganized Church, I never felt I was doing it for anybody but myself. It turned out that it was good I felt that way because every once in a while the RLDS leaders, such as Richard Howard and one-time President Wallace Smith (president of their church), said to me, “Whom do you represent?” I said, “I don’t represent anybody. This is my own personal interest.” That way they let me keep coming. If I had been a representative of the Church, I don’t think they would have let me do it.

Huntington: Describe the relationship between the RLDS Church and our church at the time you were making your visits to their headquarters in Independence.

Matthews: There really wasn’t much exchange of research between the RLDS library and our Church library. There just wasn’t a feeling of cooperation there. At least, that is the way it appeared to me. But they were very nice to me, and I wasn’t trying to tell them anything that wasn’t true. I was totally honest with them, and they believed me. They were very formal at first, but it loosened up as time went along. I did talk with Elder Bruce R. McConkie about the work I was doing with the JST because he was very interested in it. So I did talk with him about it. When the time came to make this new edition of the Bible, the Brethren organized the committee, but they did not dictate what to put in it. The Bible Committee spent the first year deciding what to include. The question came up, should we have excerpts from the Joseph Smith Translation? And it was talked back and forth and decided yes. Well, I already had a typewritten copy of most of the manuscript. I hadn’t finished it by then because this Bible Committee began in 1971. I had it well under way, and they knew that I had been all through it and that I had a relationship back there and one thing and another. So I think, although I didn’t start out with it in mind, my work with the Reorganized Church did a few things. First, it established a liaison between us. Second, I knew them personally, and they knew me, and we trusted each other. Third, I had considerable information about the manuscript that no other LDS member had. So when it came to making the new LDS edition of the Bible, they asked me to be the one to help put the JST in the new LDS edition of the Bible.

Huntington: Who was the chair of that committee?

Matthews: Elder Thomas S. Monson, because it worked by seniority. Elder Monson, Elder Boyd K. Packer, and Elder Bruce R. McConkie were the three main members of that committee.

Hauglid: Was this the Scriptures Publications Committee?

Matthews: Yes. Elder Monson had the seniority of the three, and he was automatically the chairman.

Hauglid: Who contacted you about helping them?

Matthews: I don’t remember, probably Elder Monson. The first meeting I attended was with Ellis Rasmussen, Elder Monson, Elder Packer, and Dan Ludlow. Dan was an important contributor, even though he was never really a formal member of the committee. But he was chairman of Correlation, and this was a Correlation project.

Huntington: So the manuscript that was used for placing the JST excerpts into the LDS King James Bible was taken from the typed manuscript that you copied from the original. Is that correct?

Matthews: Well, yes and no. What we did was this: I bought two printed copies of the RLDS Inspired Version, because they are printed on both sides, you know. So you had to have two copies because if you cut something off one side and you want something on the other side, you have to have another copy. I would cut out from a printed edition of the Inspired Version a passage that we wanted and glue it to a piece of paper. Then, I would cut out the verse from the King James Version and put it above the section from the Inspired Version and show at what point we wanted the JST to contribute to it. You could say the manuscript that was used was the printed Inspired Version, but I had inspected the printed RLDS Inspired Version by comparing it with the original manuscript, and I had a copy of my comparison. So, depending on how you interpret that, you could say the originals were the source, but the originals stayed in Independence, Missouri. The typesetter actually worked from the printed Inspired Version. So I had stacks and stacks of paper, eight and one-half by eleven, with King James Version passages pasted above passages from the JST and where the call letter a, b, or c should be and then how much of the JST should be included. That’s how it was done.

Huntington: But you had made corrections to their published Inspired Version that you used based on the original?

Matthews: Yes, but it didn’t take many. The printed RLDS Inspired Version is very accurate.

Huntington: That’s important to note.

Matthews: I think one of the important things out of everything I learned was that the printed Inspired Version is quite accurate. If the manuscript is accurate, the printed edition is accurate. They followed the manuscript quite carefully. There are a few little things.

Hauglid: Joseph made over three thousand changes or corrections to the Bible; isn’t that correct?

Matthews: Yes, there are 3,410 verses of the JST that are different from the KJV.

Hauglid: And the Scriptures Publications Committee used about one-third of those changes in our edition of the King James Version?

Matthews: Yes, that’s pretty close. A little more than one-third. When we were putting the cross-references and footnotes into the Bible, there was no need to do anything with the book of Moses. The book of Moses has 335 verses, I think, so we already had that many. Then we have Joseph Smith—Matthew; I think that has about fifty-five more verses. So we have approximately four hundred verses already in one of our standard works, the Pearl of Great Price. There was no need to duplicate any of those. We have in the footnotes and in the appendix in the back of our Bible about eight hundred more. That’s a little more than one-third. When we say there are 3,410 verses, a verse might have five or six changes in it. So there are that many verses of the JST that differ from the King James. That’s according to my count, and every now and again I make mistakes.

Hauglid: Why don’t we have all of the corrections Joseph made in our standard works?

Matthews: I think there are at least three reasons. A major reason is that it is copyrighted by the Reorganized Church, and we felt that they wouldn’t give it up to us just for the asking. Second, there wasn’t space. In the Latter-day Saint edition of the Bible, other things were demanding space and attention, so we didn’t have space to reproduce the entire JST in there. And we didn’t want to reproduce the book of Moses and Joseph Smith—Matthew. So those were two good reasons. I think a third reason is that some of these changes were a change of “wherefore” to “therefore.” That’s not a major doctrinal change, and there didn’t seem to be justification for putting that in. There’s another thing, too, and that is if you’re reading a whole paragraph and the corrections are in the paragraph, the context is clear. But when you take one word and put it in the footnote at the bottom of the page, you lose some of the context. There were, sometimes, little nuances in the JST that we felt weren’t valuable enough to merit a place in the new Bible.

Huntington: Did the Scriptures Publications Committee need to get permission from the RLDS Church to include the changes that we used in our edition of the King James Bible?

Matthews: I don’t know if we had to or not, but we did. The Brethren are very interested in maintaining relationships. The committee said to me, “Sometime when you’re in Missouri, sit down with their historian and show him every one of the passages that we want to use and see if we can get permission to do that.” I did that; I took him a list.

Huntington: This was Richard P. Howard?

Matthews: Yes, this was Richard P. Howard. I had a typewritten list. I said, “We’d like to use all of these things.” He said, “Well, I’m sure that’s all right. I’ll have to get it cleared.” So they worked it out between the two publishing houses, between Deseret Book and Herald House, which is the RLDS publishing house. It’s all written up properly, and for the exchange of one dollar paid to the RLDS Church, to make it a legal document, Deseret Book got permission to use those corrections. I feel that if we had asked for everything, if we had said to them, “We want everything in the JST,” they might have said no, and maybe we would not have anything. But we thought that it was in the part of good judgment to get those that were most doctrinal, and, in fact, I wrote up a list of principles governing what we wanted to use. If it dealt with priesthood, if it dealt with the Atonement, if it dealt with the house of Israel or any other doctrinal concept, we wanted it. This list was published in an Ensign article in June 1992.[2]

Hauglid: Did your work with the JST result in any contribution to the other standard works?

Matthews: Yes, it did in several ways. One is that some of the headings in the Doctrine and Covenants now mention the JST when they didn’t used to. There are also footnotes in the current edition of the Doctrine and Covenants that use the JST. Plus, I had noticed through the years that sometimes almost the identical words, half a sentence or so, would be in the Doctrine and Covenants, as it appeared in the JST and often similar doctrines, but I didn’t know which came first. It was the popular view of many people that after he had a revelation in the Doctrine and Covenants, Joseph Smith would then go the Bible and correct it. I discovered by working with the manuscript that it was just the opposite. I noticed when I first saw the manuscript that there were frequent dates at the top or the middle of the page. I also noticed that the handwriting changed from one scribe to the other from time to time. None of that was interesting at first to me, but as time went along and I became more familiar with the JST and with the manuscript, I realized that according to the dates that are written in the manuscript, some of those concepts were revealed in the JST before they appeared in the Doctrine and Covenants. One is the age of accountability, which shows up in the JST chapter of Genesis 17 in about April 1831. It doesn’t show up in the Doctrine and Covenants until November 1831 in section 68. That’s just one example. There are maybe a dozen such instances, where things occurred in the manuscript of the JST at an earlier date than they occurred in the Doctrine and Covenants.

So that gave me, and I have tried to persuade others, a whole new view of the historicity of the Doctrine and Covenants and its relationship to the JST. They are not two entirely separate books; they’re interwoven. They are not just two books with similar roots; they have the same root—revelation. Many of the revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants were stimulated and initiated by passages in the JST—section 76 is a major one, but there are others such as section 91 and much of section 88. You know, Scott Faulring and Kent Jackson have been doing a very careful study of the manuscript. One of the things they have been able to do that I was not able to do is to determine more carefully just when certain portions of the JST were actually made. They discovered that large portions of it were earlier than we had known before. So the concept of being a forerunner to the Doctrine and Covenants is even stronger now than it was when I did it. I had grasped the idea, but they have provided a great amount of confirming evidence. That, I think, is a major thing.

Then, too, in the new edition of the Pearl of Great Price, you notice each chapter of the book of Moses has a heading as to when it was received. That didn’t used to occur in the former editions of the book of Moses, since they had some of the wrong dates. We were able to correct the dates.

Huntington: Did those new dates come from your work on the JST?

Matthews: Yes.

Hauglid: The LDS Church had the opportunity a few years ago to clean and preserve the JST manuscripts and marked Bible. What can you tell us about that?

Matthews: I was not directly responsible for that exchange of work, but perhaps I did open the door between the two churches for research and study. In 1995, the Reorganized Church made an agreement for our church’s Historical Department to do some conservation work. They washed them. Somebody through the years had patched some of the JST manuscripts with mending tape. You know mending tape that long ago would get brittle and go dark. Our manuscript experts in Salt Lake City removed that tape. They put the manuscripts in mylar folders, each one of them. Some places where pages had crumbled and wrinkled along the edges have been repaired. There were some repairs to the marked Bible. The cover was worn. They put a new cover on it. It has had two good effects. First, the manuscripts are much cleaner, and you can read them now where the tape had once been. Second, some of the pages had become wrinkled. They would wet them and straighten them and let them dry straight, so they really have preserved them.

A number of years ago there was a major exchange of documents between the two churches. Again, I didn’t broker that, but I may have had something to do with it, as I said before, opening the door so that there was more contact between the two churches. But there was a major exchange. The Reorganized Church had some letters and documents that we wanted. We had things that they wanted. The exchange between the two churches was written up in the Church News, and it was quite interesting.

I was talking to President Alvin R. Dyer one day about that. He said, “Well, we gave them more then they gave us. They got the better of the deal.” I was back in Independence, and I was talking to Richard P. Howard one day, and Richard said, “You know, we gave you more than you gave us. You got the better of the deal.” I thought, “Well, isn’t that interesting?” I didn’t tell them what the others had said. I talked with Elder McConkie about it. He said, “Who cares? They got what they wanted; we got what we wanted. Who cares who got the better deal?” I thought that was impressive.

Huntington: What other benefits came to you and others as a result of your contact with the RLDS Church?

Matthews: I probably never would have made so many trips to Missouri had it not been that my attention was focused on that manuscript. As a result of going there, I became very well acquainted not only with the work of Joseph Smith and with the Bible but also with many other things. For one thing, I became more acquainted with the geography of Missouri. Not every trip, but often, when I was in Independence, we would take side trips over to Liberty, Adam-ondi-Ahman, or Far West. We’d go to Richmond and visit the cemeteries. Sometimes I did that alone. Sometimes I did that with Larry C. Porter and Richard L. Anderson.

During other trips I would visit with the Reorganized Church historian, and I got their views about a lot of things, so it was very helpful as far as what it did for me in understanding that period in Church history. I was able to read many letters written by Joseph Smith III and got his views about several things. I met some very fine people such as Richard P. Howard, the RLDS historian. I met W. Wallace Smith, who was the president of the RLDS Church and the grandson of Joseph Smith. I met Wallace B. Smith, who was Wallace’s son and a future president of the RLDS Church. My first visit there I met a man, a member of the RLDS First Presidency named F. Henry Edwards, and he was very pleasant; he was an Englishman and very talkative. He had married one of Joseph Smith III’s daughters, so his children were descendants of Joseph Smith, and I met two of his sons, one Lyman Edwards and another Paul Edwards. They are both rather prominent in leadership in the RLDS Church, particularly in the academic area. It was wonderful to meet and discover what good and hospitable people they are. So through it all, as the years went by, I became acquainted with an RLDS archivist named Ronald E. Romig, who’s been to BYU several times, and one of his assistants, Barbara Bernauer. I became friends with them and appreciated their hospitality. Also, the Reorganized Church’s current historian, Mark Shearer, is a very special man. On one of my early visits, there was a young man who worked in their Historical Department by the name of Grant McMurray. He was a young, slender, gracious, friendly man, and he’s now president of their church. About a year ago at one of their conferences, he quoted me, and I thought that was rather amazing.

What other benefits besides the JST have come to me? I feel like I am much more acquainted with Church history during the Missouri era than I would have been had I never been there. I met some very fine people and also learned much more about the death of Joseph Smith and the burial and moving of Joseph’s and Hyrum’s bodies from one place to the other. They have a much more detailed account of that than we have in our records, and I have been fortunate enough to read the RLDS materials, so it has been good for me in many ways.

Hauglid: What would you most like the members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to know about the Joseph Smith Translation?

Matthews: As I indicated earlier, when I was doing this work, I never thought I had a message for anybody; I was deeply and sincerely interested in Joseph Smith’s work with the Bible. But as the years have gone by, I have been able to see that it had some intrinsic value for members of the LDS Church, not only as a historical thing, but I’d like the members of both churches to be thoroughly convinced that Joseph Smith’s work with the Bible was a very important doctrinal work. I would like them to know that it was true, that it is important, that his work with the Bible was a command from the Lord. In the Doctrine and Covenants, the Lord frequently tells him to do it. There is a great lesson for all of us in that because in reading the Bible and concentrating, praying, and meditating, the Prophet Joseph received revelation. That is the way the Lord teaches the gospel to His people. When you study the scriptures, you are going to learn and receive revelation.

The Prophet Joseph was inspired to make many corrections and alterations, as well as to add much new background information in various places in the Bible. Reading the JST is like having Joseph Smith for a study companion because you get his views on how he understood certain things. I think the JST has been underappreciated by many people in both churches but, particularly, I think, by our people, because it was not brought to Utah, and then when it was published it was done by the Reorganized Church, so for some it had a little cloud hanging over it. I hope now that cloud has vanished. I think even our scholars have barely understood that the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible has a very direct relationship to the Doctrine and Covenants, to the doctrines that we believe in the Church. I have frequently said that every person who has joined the Church since 1831 has been affected by the JST, even though he or she did not know it. It was in the JST where the revelation was first given on the age of accountability for baptism. Then, in 1832, the revelation on the three degrees of glory was an outgrowth of his work with the Bible. Most of what we know about Adam and Melchizedek and eternal marriage and priesthood organization originated in the JST. There are many things that were outgrowths of revelation received while he was working with the Bible. It is a very prominent and important part of our history, and it ought to be a part of our present understanding. With the footnotes and the appendix in our edition of the Bible, I think the decision has already been made by the Brethren that the JST should be a part of our scripture study. Had it not been so, it would never have been put in this new edition of the Bible.

Robert J. Matthews’s Trips to Work on the Joseph Smith Translation

|

Visit |

Date |

Purpose |

|

1 |

June 20, 1968 |

RLDS Auditorium. Visited with Richard P. Howard and W. Wallace Smith. Saw photocopies of the Inspired Version manuscript and Joseph Smith’s marked 1828 Phinney Bible. |

|

2 |

November 1–6, 1968 |

With Larry C. Porter. While Brother Porter did this research, I copied all the markings from the Joseph Smith Phinney Bible into a copy of the King James Bible I bought for this very purpose. It required seventeen hours of diligent work. Examined the marked Bible carefully. Also worked with photocopies of the handwritten manuscript. |

|

3 |

July 27–August 3, 1969 |

With Richard L. Anderson. While Richard did his research, I spent all week reading and making handwritten notes from the Inspired Version manuscript (photocopy). |

| 4 | September 7–12, 1969 | For the first time I examined the original manuscripts, beginning on September 12, my forty-third birthday. Began typing the manuscript (New Testament 1). Did nearly one hundred pages this week. Working with originals was a great thrill. |

| 5 | February 7–14, 1970 | Spent most of the week with the RLDS 1866 committee manuscript. Also compared my copy of the Bernhisel manuscript with the originals, identifying passages and manuscript sources. |

| 6 | Week of August 4, 1970 | Continued copying the manuscript all week in both Old and New Testaments. |

| 7 | Week of November 4, 1970 | Continued copying the manuscript all week, including Acts through Revelation. Also met BYU Religious Education faculty and MHA persons at Graceland College in Lamoni, Iowa, and visited Missouri sites with them. At the time, I was still employed by seminaries and institutes. |

| 8 | June 19–26, 1971 | Typed Old Testament manuscript from Isaiah through Malachi. Also visited with President W. Wallace Smith and his counselor, President F. Henry Edwards. |

| 9 | Week of April 11, 1972 | Spent all week copying the Old Testament manuscript from Exodus through 1 Kings. |

| 10-12 | Exact dates not recorded | Made three trips to Independence, checking my typescript with the originals and also reading letters, diaries, publications, and Inspired Version articles in the Saints’ Herald. |

| 13 | January 3–10, 1974 | Worked all week in RLDS Library copying and comparing my typescript with the original and reading from Joseph Smith III letterbook. |

Notes

[1] In late 2004, the Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University will publish a new transcription of all the original manuscript pages of the Joseph Smith Translation. Brother Matthews is one of the editors of this project. See Scott H. Faulring, Kent P. Jackson, and Robert J. Matthews, eds., Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2004).

[2] Robert J. Matthews, “I Have a Question,” Ensign, June 1992, 29.