Nephi: An Ideal Teacher of Less-Than-Ideal Students

Tyler J. Griffin

Tyler J. Griffin, "Nephi: An Ideal Teacher of Less-Than-Ideal Students," Religious Educator 13, no. 2 (2012): 61–71.

Tyler J. Griffin (tyler_griffin@byu.edu) was an assistant teaching professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this article was published.

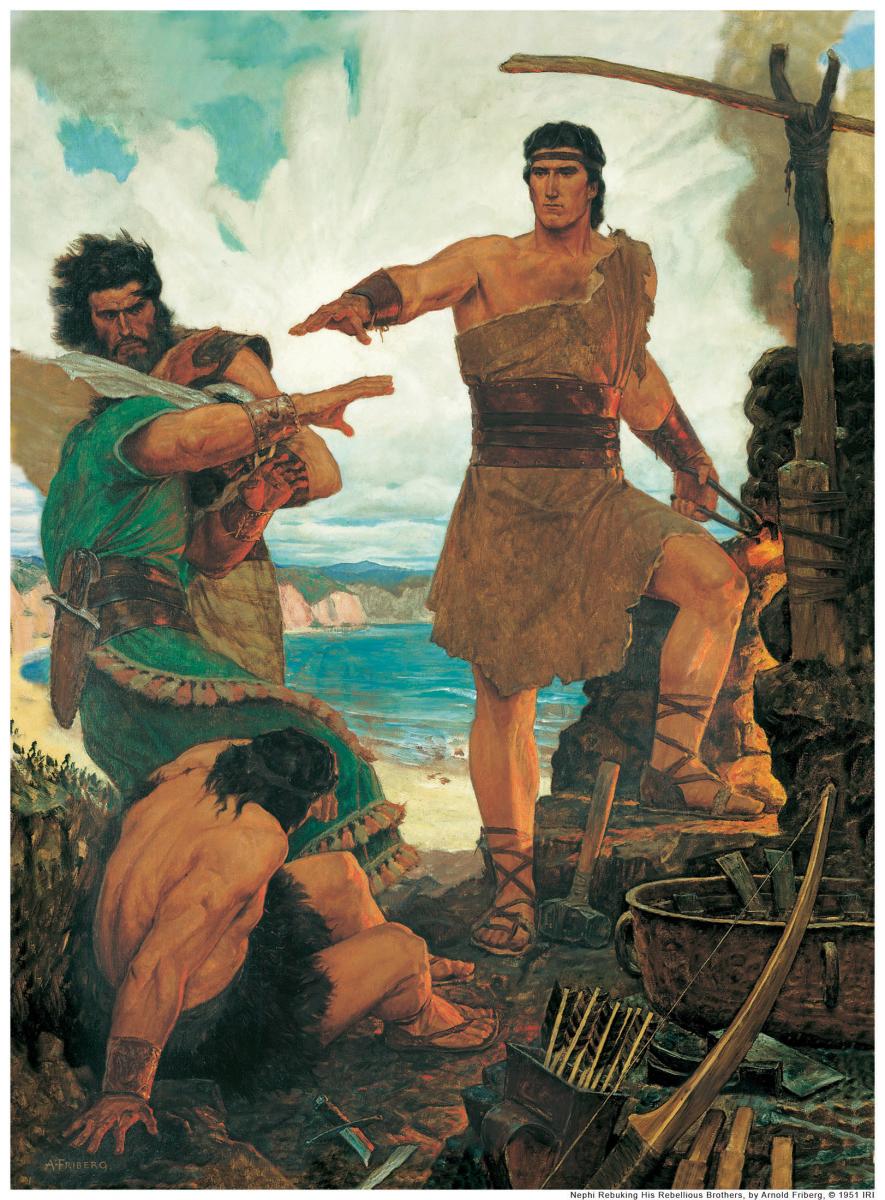

Laman and Lemuel's approach to life repeatedly demonstrated a rash, reactionary mentality. When things got tough, they responded with murmuring and misplaced aggression. Arnold Friberg, Nephi Rebuking His Rebelious Brothers, © 1951 Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Laman and Lemuel's approach to life repeatedly demonstrated a rash, reactionary mentality. When things got tough, they responded with murmuring and misplaced aggression. Arnold Friberg, Nephi Rebuking His Rebelious Brothers, © 1951 Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Many books and papers have been written on what Nephi experienced as a learner under the tutelage of the Spirit and the angel in 1 Nephi 11–14. Ironically, his experience as a student on the mountaintop was immediately followed by many opportunities for him to become a teacher in the wilderness to his family. Nephi’s interactions with the Spirit and the angel likely served as more than just a vision and discovery of eternal truths; his divine tutelage could also have served as a teacher-training experience. This idea leads us to ask the following questions: (1) What information exists in the chapters immediately following Nephi’s vision that reveals what kind of learners Laman and Lemuel were compared to Nephi? (2) Is there any textual evidence in chapter 15 that Nephi employed the same methods and approaches with his brothers that had been so effectively used on him by his own heavenly tutors? (3) What can we discover about learning and living by comparing and contrasting Nephi and his brothers through their wilderness wanderings in chapter 16? And finally, (4) what implications might these chapters and their principles hold for teachers and students of the gospel in our day?

The Role of the Student: Comparing Nephi with His Brothers in Chapter 15

What kind of a learner was Nephi? How well did Laman and Lemuel fulfill their roles as learners? All three of them were students in the same “classroom” of 1 Nephi 8 with father Lehi as their teacher and his dream as the subject matter. Nephi had a drastically different student experience than his two brothers did. Hearing the words of his father caused Nephi to magnify his role as a learner. It was not good enough for Nephi to hear about his father’s experience. Instead, he stated, “I, Nephi, was desirous also that I might see, and hear, and know of these things” (1 Nephi 10:17). A major key that unlocked his role as a learner was revealed in the next phrase of this verse: “by the power of the Holy Ghost.” Nephi was not just entertained, intellectually stimulated, or emotionally moved by Lehi’s role as a teacher. Nephi recognized the true source of Lehi’s teachings and the power that he felt as his father taught. Another key was that he desired to know those same things for himself, from the same source from which his father had received them. He also believed “that the Lord was able to make them known unto [him]” (1 Nephi 11:1). But he was not content to sit idly and wait for revelation to come to him. As he “sat pondering in [his] heart [he] was caught away in the Spirit of the Lord” (v. 1). By appropriately fulfilling his own role as a learner, he invited the Holy Spirit to fulfill his role as the ultimate teacher. Chapters 11 through 14 contain the rich reward for Nephi’s effort and faith.

What about Laman and Lemuel as learners? Their response to Lehi’s teaching was not revealed until after Nephi had finished his vision and returned to the camp in chapter 15. How excited Nephi must have been returning to the tent of his father. Imagine his joy at knowing he had not only experienced “the things which [his] father [had seen]” (1 Nephi 11:3) but also gained additional insights into his father’s dream. Consider how frustrating it must have been for Nephi to be welcomed into camp by his brothers “disputing one with another concerning the things which [Lehi] had spoken unto them” (1 Nephi 15:2). Laman and Lemuel had failed to hear or recognize the whisperings of the Spirit during their father’s teachings. Having cut themselves off from the Spirit as their guide, they were left with only a few alternatives: (1) go to Lehi and ask follow-up questions on what he had taught, (2) discuss with each other what Lehi’s words meant to them, (3) argue with each other about what Lehi had said, or (4) totally ignore and disregard what Lehi had said. Unfortunately, they chose the third option. Nephi instantly recognized the source of their problem, that “they being hard in their hearts . . . did not look unto the Lord as they ought” (v. 3).

Nephi’s mountaintop experience would have been exhausting in every way, but seeing his brothers’ lack of faith and their disputations must have taken an additional toll on him. He gave one short line in verse 6 to hint that he was overwhelmed: “after I had received strength I spake unto my brethren” (emphasis added). And with that statement, Nephi began what would prove to be a mostly frustrating series of interactions with his brothers as their teacher.

Nephi began his “class” similarly to how the Spirit had begun with him, by asking a few questions. His brothers’ responses helped Nephi determine their level of readiness to learn. Nephi used what he had observed in his students’ behavior and “[desired] to know of them the cause of their disputations” (v. 6). Nephi modeled for us a wonderful example of not jumping to conclusions about students’ behavior until they have been given a chance to account for their own actions. Unfortunately, Laman and Lemuel’s response in verse 7 revealed a complete lack of understanding of Lehi’s teachings. Nephi’s logical follow-up question reiterated his own reflexive reaction as a learner: “Have ye inquired of the Lord?” (v. 8). Even though he was asking a question, Nephi was also teaching by example when he humbly acknowledged the true source of learning with his simple, faith-filled question. Therefore, he was hoping that his students had done that which continually came so instinctively to him. Laman and Lemuel’s answer proved to be a significant turning point for Nephi as an instructor. They said, “We have not; for the Lord maketh no such thing known unto us” (v. 9).

That answer exposed the major chasm between Nephi and his brothers as learners. Nephi had used his agency to act; he consistently sought to learn “by study and also by faith” (D&C 88:118). Laman and Lemuel, however, regularly waited “to be acted upon” (2 Nephi 2:14). Because of their lack of faith and action, Nephi could not use many of the more powerful teaching techniques that had been so effectively used on him by the Spirit and by the angel in his own learning. Many religious educators today might consider Nephi’s teaching techniques with Laman and Lemuel less effective. However, Laman and Lemuel’s reactions to Nephi’s teaching forces us to acknowledge that students’ willingness to appropriately fulfill their role in learning has a significant effect on both what and how a teacher teaches.

A final observation on Laman and Lemuel as learners might be helpful to contextualize what skills and willingness they brought with them to Nephi’s “classroom.” There is no textual evidence in the Book of Mormon that Laman and Lemuel ever read from the brass plates or made any records of their own proceedings. We never find them reading from the scriptural record. Instead, Nephi used phrases like, “I did read many things to them, which were engraven upon the plates of brass, that they might know concerning the doings of the Lord in other lands. . . . And I did read many things unto them which were written in the books of Moses. . . . I did read unto them that which was written by the prophet Isaiah” (1 Nephi 19:22–23; emphasis added). These plates were written in Egyptian, while they spoke Hebrew (see 1 Nephi 1:2; Mosiah 1:4).

[1] It would have required extra effort on their part to master scripture reading and writing. It is possible that Laman and Lemuel read the scriptures, but Nephi chose not to mention it. Another possible scenario is that Laman and Lemuel were capable but simply chose not to read the plates. This would be similar to many people today who know how to read but choose not to spend any time in the scriptures for themselves. One more potential scenario is that Laman and Lemuel had never taken the time and effort to learn the language of scriptures. Whatever the real situation was, it is apparent that Laman and Lemuel relied on Nephi to read and interpret the scriptures for them.

Two additional factors later in the Nephite and Lamanite story may help inform us on this issue: (1) Omni 1:17 reveals the consequences of people who do not have scriptures or who do not use them. The early Lamanites fulfill all of these results perfectly—they had many wars and serious contentions (e.g., Jacob 7:24; Omni 1:10; Words of Mormon 1:13; Mosiah 9:13–18; Alma 24:20), their language had become corrupted (Omni 1:17; Mosiah 24:4), and they denied the existence of their creator (Mosiah 10:11–12). If Laman and Lemuel had valued the words on the brass plates, they could have made their own copy of the record before Nephi left in 2 Nephi 5:5. Instead, their tradition was that Nephi had stolen the plates from them (see Mosiah 10:16). (2) Consider how other writers in the Book of Mormon clearly stated that they had been “taught in all the language of [their] fathers (Mosiah 1:2; see also 1 Nephi 1:2–3; Enos 1:1). Based on many clues of how sluggishly Laman and Lemuel fulfilled their role as learners in most other settings, it would not be surprising to find that they had simply refused to put forth the effort to master the skill of reading scriptures and thus had to rely on Nephi and Lehi to read from the plates for them. A lack of scriptural literacy would greatly affect their ability to learn and would help explain more clearly why Nephi chose to read and tell them so much rather than let them participate and discover more truths for themselves.

Nephi’s Teaching Topics and Techniques in 1 Nephi 15

Nephi’s heavenly tutelage was very interactive. He and his heavenly teachers effectively used various levels of questioning to help him discover or understand many eternal truths. As a teacher of Laman and Lemuel, however, Nephi rarely chose to repeat this collaborative pattern. Once Nephi diagnosed Laman and Lemuel’s lack of faith and their unwillingness to ask the Lord for help, he abandoned the interactive teaching techniques with which he had begun. From that point forward, Nephi’s teaching became predominantly one-sided, relying heavily on telling them what everything meant. In 1 Nephi 15:9–20, Nephi asked seven questions, none of which Laman and Lemuel answered because they were all rhetorical in nature. Nephi hinted that his initial speech was much longer than the twelve verses we have in the record. He used phrases such as “I, Nephi, spake much unto them concerning these things” (v. 19) and “I did rehearse unto them the words of Isaiah. . . . I did speak many words unto my brethren” (v. 20). Rather than asking them what they understood, Nephi simply told them “this is what our father meaneth” (v. 17). Thankfully, even with students who struggle, an inspired teacher like Nephi can still have a positive impact. This is illustrated when Nephi wrote, “They were pacified and did humble themselves before the Lord” (v. 20). This pacified attitude led them to interact once again with Nephi in verse 21.

What might religious educators today learn from Nephi’s choice to deliver such lengthy, one-sided lectures? Ideally, his brothers would not have relied so heavily on him for their learning. They had the capacity to eventually experience the same vision he had received from heaven. However, Laman and Lemuel seemed unwilling to exercise their agency and faith to the required degree for that to happen. For them as learners, the first small step was to gain some humility and incrementally increase their faith. As we saw in verse 20, Nephi’s technique seems to have been successful in helping them take those first small steps as learners.

Building on their foundation of basic humility, Laman and Lemuel started to take some responsibility for their learning by asking specific questions about four of the objects in Lehi’s dream (vv. 21, 23, 26, and 31). In responding to their questions, Nephi used the phrase “And I said unto them” (or some variation of it) seven times (vv. 22, 24, 27, 28, 29, 30, and 32) and “I did exhort them” twice in verse 25. He finished with, “And thus I spake unto my brethren. Amen” (v. 36). Once again, Nephi clearly dominated the “talk time” and made most, if not all, of the symbolic connections for them. The one constant for them as learners seemed to be that they were willing to listen to Nephi at that time.

Chapter 16 opens with Laman and Lemuel’s reaction to all of Nephi’s words in the previous chapter. They were overwhelmed by his teachings in their initial response (see v. 1). After giving them two more verses of explanation, Nephi finished by saying he “did exhort [his] brethren, with all diligence, to keep the commandments of the Lord” (v. 4). The happy ending of this learning experience is that Laman and Lemuel “did humble themselves before the Lord” (v. 5). Unfortunately, their humility proved to be slowly gained and quickly lost.

Out of the “Classroom” of Chapter 15 and into the “Laboratories” of Chapter 16

The more traditional teacher-student interactions between Nephi and his brothers are replaced in the rest of chapter 16 with the family breaking camp to follow the directions of the Liahona through the wilderness. Even though there is very little direct dialogue recorded between Nephi and his brothers in this chapter, their responses to life lessons reveal a great deal about them as students. By analyzing how they responded in life’s “laboratory,” we can learn much about them that helps clarify and give context to their behavior in the more traditional learning settings with Nephi.

Laman and Lemuel’s approach to life repeatedly demonstrated a rash, reactionary mentality. If things were going well, then they were happy. When things got rough, however, they responded with murmuring and misplaced aggression rather than doing that which might have improved their situation. This “victim-by-choice” versus “agent” disparity between Nephi and his brothers was clearly revealed when things first got rough in the family’s journey. Nephi broke his bow in verse 18. Laman and Lemuel became “angry with [Nephi] because of the loss of [his] bow.” The unwritten implication is that they were completely relying on Nephi to provide food for the group since their bows had “lost their springs” (see v. 21), and he had let them down. Under normal circumstances, it would be reasonable to expect the older brothers to be the ones responsible for providing food for the family. Rather than finding a solution to their problem or discussing their options, they chose to react with anger against Nephi. This “laboratory of life” crisis revealed another manifestation of their “victim-by-choice” mentality that seems consistent with their approach to learning in their “classroom” settings. In chapter 15 and most other formal gospel-learning settings, Laman and Lemuel consistently relied on Nephi to figure out the answers and then “feed them” what they needed spiritually.

Their murmuring intensified once they all returned to camp empty-handed: “Laman and Lemuel . . . did begin to murmur exceedingly, because of their sufferings and afflictions in the wilderness; and also my father began to murmur against the Lord his God” (v. 20). Some of Nephi’s most powerful teaching took place by his example in that critical moment. He chose to act rather than passively wait for a solution to appear by complaining about their situation. He made a new bow and an arrow and then asked his father where he should go to find food. That was an outward manifestation of how Nephi repeatedly fulfilled his role as an active learner. He did all in his power to solve problems while trusting completely in the Lord, whether he was seeking revelation or seeking food.

Nephi’s faithful example and words of encouragement engendered a fresh humility in the entire group (see v. 24), even with unfulfilled hunger. When he finally returned with food, “how great was their joy!” (v. 32). Unfortunately, their teachability and gratitude only lasted until the next trial in their journey, when Ishmael died at Nahom (v. 34). This experience again revealed a major flaw in Laman and Lemuel as learners. They were turned inward so much that they never seemed to notice that Nephi was suffering through the same trials they were facing. He had likely been just as hungry as they were when his bow broke, and Ishmael was his father-in-law too. Laman and Lemuel’s self-absorbed approach to life reflects learners in formal classroom settings who harden their hearts and limit what a teacher can do.

After Ishmael’s death, Laman and Lemuel’s murmuring intensified to the point of their saying, “Let us slay our father, and also our brother Nephi, who has taken it upon him to be our ruler and our teacher, who are his elder brethren” (v. 37). What an ironic statement! Since they were unwilling to act for themselves, Nephi had been providing for them physically and spiritually. Only the voice of the Lord in verse 39 could subdue them to where they “did repent of their sins, insomuch that the Lord did bless us again with food, that we did not perish” (v. 39).

One of the potential bright spots for Laman and Lemuel was what Nephi mentioned as a time when they did “wade through much affliction in the wilderness” as well as “bear their journeyings without murmurings” (1 Nephi 17:1–2). Unfortunately, they spent eight years in that wilderness covering a distance that should have taken them far less time to travel. Alma gave us his thoughts on why the trip took so long: “Therefore, they tarried in the wilderness, or did not travel a direct course, and were afflicted with hunger and thirst, because of their transgressions” (Alma 37:42). This same problem was manifest in their learning. Because of faithlessness and transgressions, Laman and Lemuel took much longer than necessary to learn the lessons the Lord had in store for them.

Ultimately, Laman and Lemuel’s periods of humility and faith decreased in power and frequency until the brothers grew completely hardened and plotted to kill Nephi (see 2 Nephi 4:13–14; 5:1–4). Rather than allowing them to kill him, Nephi chose to follow the promptings of the Lord. He took those who would follow him and permanently left his brothers (2 Nephi 5:5–6). He had done all he could for them as a brother and a teacher while still respecting their agency. Nephi had other, more receptive students to teach, whose willingness to learn allowed him to teach beyond rudimentary levels. As readers of his words in the latter days, we too are a part of Nephi’s “classroom.” If we fulfill our roles in learning, we will be blessed by Nephi’s powerful teachings that include some of the most sublime doctrines and principles ever recorded (see 2 Nephi 5–33).

Implications and Teaching Ideas for Religious Educators Today

Let us now analyze these stories in the broader context of the plan of salvation and look for implications, teaching approaches, and applications for us in our roles as learners and teachers today.

- Knowing that the Book of Mormon was written for our day, it is important for us to recognize the powerful contrast between the learning and living approaches of Nephi and his brothers. As with all good people in the scriptures, Nephi provided us with a powerful type of the Savior, while Laman and Lemuel repeatedly exemplified the opposite. Jesus never murmured or waited for others to do his work for him. Conversely, Satan wanted all the rewards without paying the necessary price. Then, when things did not go his way, he chose the path of murmuring and feeling wronged rather than taking responsibility and making proper adjustments that could have led to his eternal happiness.

Nephi modeled for us a wonderful example of not jumping to conclusions about students' behavior until they have been given a chance to account for their own actions. Photo by John Luke, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Nephi modeled for us a wonderful example of not jumping to conclusions about students' behavior until they have been given a chance to account for their own actions. Photo by John Luke, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.The contrast of learning roles carries many implications for religious educators today. Much of what teachers do in the classroom is determined by how well their students fulfill their roles. How frustrating it must have been for Nephi to have so much to share with his brothers and yet be forced to go back to the most elementary teachings while using the most basic of techniques! If we help students see these chapters as a handbook for becoming more like the Savior in their role as learners, they will be more likely to shun the temptation to shirk that role and less likely to follow the path taken by Laman and Lemuel as learners. Teachers can often activate the role of their students with simple reminders to consider whose example they want to follow. This will help invite greater revelation in their individual and collective learning, both in classroom settings and in the “laboratories” of their lives.

- Laman and Lemuel repeatedly went back to feeling wronged or acted upon, both in their learning and their living. A simple object lesson that teachers could use to illustrate this approach to living and learning is a thermometer. If it is hot, the thermometer reacts by going up. When it is cold, the thermometer drops accordingly. Watching Laman and Lemuel throughout the story is much like watching a thermometer through changing climates. Conversely, an object that symbolizes Nephi’s approach to life and learning is a thermostat, which has the ability to read its surrounding conditions and cause desired changes on that environment. Nephi repeatedly recognized poor conditions around him and used his agency to try to improve the situation rather than feeling powerless and offended by it. This action-oriented approach was reflected in the examples of his life and in the way he tried to influence Laman and Lemuel for good in his teaching.

- The end of the story for Nephi as a student of heavenly tutors and as a teacher of his people is quite remarkable. He began his life listening to his father and believing his words. He paid the price to be able to read and write scriptures in the Egyptian language. He learned to hear, recognize, and follow the voice of the Spirit guiding him throughout the beginning chapters of his story. He progressed to conversing directly with the Spirit and with an angel in chapters 11–14. Fast-forward to 2 Nephi 29 and we find Nephi acting as a scribe for the Lord. In 2 Nephi 31, he is hearing and recording not only the voice of the Son (vv. 12, 14) but also the voice of the Father (vv. 11, 15). What a remarkable finish to a remarkable life as a learner and teacher to be tutored by the Savior and Heavenly Father directly!

Conclusion

All of us have the capacity to become more like Nephi in our roles as learners. Unfortunately, we also have the capacity to become more like Laman and Lemuel in that same role. Perhaps helping our students see this stark contrast might be enough for many to make improvements in the way they choose to learn in our classrooms and live their lives. Seeing Nephi’s faithful action as a symbol of the Savior’s perfection might be the motivation that some students need to stop sitting back and waiting for teachers to do all the work. At that point, they may choose to more fully engage in their study of the gospel with the help of the Holy Ghost and inspired teachers and thus progress in their appropriate use of agency. When more of our students do this, our abilities to more powerfully fulfill our teaching roles will increase.

Notes

[1] The exact nature of the “language” of all the texts written on the brass plates continues to be debated. Part of the challenge is that nowadays we differentiate between language and script. For example, a number of different European languages are written with the same Roman script. Recognizing and reading the script does not guarantee that one knows and understands the language. When Benjamin indicates that Lehi had “been taught in the language of the Egyptians therefore he could read these engravings” (Mosiah 1:4), he is likely referring to both language and script. However, as Brian Stubbs has observed: “Whether it was the Egyptian language or Hebrew written in Egyptian script is again not clear. Egyptian was widely used in Lehi’s day, but because poetic writings are skewed in translation, because prophetic writings were generally esteemed as sacred, and because Hebrew was the language of the Israelites in the seventh century b.c., it would have been unusual for the writings of Isaiah and Jeremiah—substantially preserved on the brass plates (1 Ne. 5:15; 19:23)—to have been translated from Hebrew into a foreign tongue at this early date. Thus, Hebrew portions written in Hebrew script, Egyptian portions in Egyptian script, and Hebrew portions in Egyptian script are all possibilities” for how various texts were represented on the brass plates. Brian D. Stubbs, “Book of Mormon Language,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 1:180.