Standing Together for the Cause of Christ

Jeffrey R. Holland

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, "Standing Together for the Cause of Christ," Religious Educator 13, no. 1 (2012): 11–19.

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles when this was written.

The following address was given to Christian leaders in Salt Lake City, March 10, 2011.

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland. © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

I am honored to be with you tonight and am grateful you have chosen to visit Salt Lake City. You have not asked me here to make—nor would I accept the invitation to make—some sort of ecumenical statement. There is nothing of that in what we are doing. We all are who we are and believe what we believe. In saying that, I acknowledge at the outset important doctrinal differences between us. But I also acknowledge that what we have in common is good, so extensive and so potentially powerful in addressing the ills of society, that we ought in the fellowship of Christ to know and understand each other better than we do. It is in that spirit that I come tonight.

My remarks here will be my own and carry no official declaration from the Church. That is the spirit in which I have come, extending to you not only my own affection and goodwill but also that of my colleagues who constitute the presiding officers of our Church. At the close of your conference meetings, we hope you will leave knowing that you were both loved and welcome here and that perhaps a significant step forward in the Christian community has been taken.

Friends, you know what I know—that there is in the modern world so much sin and moral decay affecting everyone, especially the young, and it seems to be getting worse by the day. You and I share so many concerns about the spread of pornography and poverty, abuse and abortion, illicit sexual transgression (both heterosexual and homosexual), violence, crudity, cruelty, and temptation, all glaring as close as your daughter’s cell phone or your son’s iPad. Surely there is a way for people of goodwill who love God and have taken upon themselves the name of Christ to stand together for the cause of Christ and against the forces of sin. In this we have every right to be bold and believing, for “if God be for us, who can be against us?” (Romans 8:31). You serve and preach, teach and labor in that confidence, and so do I. And in doing so I believe we can trust in that next verse from Romans as well, “He that spared not his own Son, but delivered him up for us all, how shall he not with him also freely give us all things?” I truly believe that if across the world we can all try harder not to separate each other from the “love of Christ,” we will be “more than conquerors through him that loved us” (vv. 35, 37).

I don’t need to tell anyone in this room that Latter-day Saints and more traditional Christians have not always met on peaceful terms. From the time in the early nineteenth century when Joseph Smith came from his youthful revelatory epiphany and made his bold declaration regarding it, our exchanges have too often been anything but cordial. And yet, strangely enough—and I cannot help but believe this to be a part of a divine orchestration of events in these troubled times—LDS and Christian academics and church figures have been drawn together for a number of years in what I think has become a provocative and constructive theological dialogue. It has been an honest effort to understand and be understood, an endeavor to dispel myths and misrepresentations on both sides, a labor of love in which the participants have felt motivated by and moved upon with a quiet force deeper and more profound than a typical interfaith exchange.

The first of those formal dialogues took place in the spring of 2000 at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, where, in an earlier life, I served as president. Among our guests were Richard Mouw of Fuller Theological Seminary; Craig Blomberg of Denver Seminary; Greg Johnson of Provo, Utah; Craig Hazen of Biola University; David Neff of Christianity Today; and Carl Moser, currently on the faculty at Eastern University in Philadelphia. On the LDS side, participants included Stephen Robinson, Robert Millet, Roger Keller, David Paulsen, Daniel Judd, and Andrew Skinner, all from Brigham Young University. Names and faces have changed somewhat, but the dialogue has continued.

I am told that over the next decade they came prepared (through readings of articles and books) to discuss a number of doctrinal subjects, including the Fall of man, the Atonement of Jesus Christ, scripture, revelation, grace and works, Trinity/

As the dialogue began to take shape, it was apparent that the participants were searching for a paradigm of some sort, a model, a point of reference—were these to be confrontations? Arguments? Debates? Were they to produce a winner and a loser? Just how candid and earnest were they expected to be? Some of the Latter-day Saints wondered: Do the “other guys” see these conversations as our “tryouts” for a place on the Christian team? Is it a grand effort to “fix” Mormonism, to make it more traditionally Christian, more acceptable to skeptical onlookers? In turn, some of our Christian friends wondered: Are those “other guys” for real? Or is this just another form of their missionary proselytizing? Is what they are saying an accurate expression of LDS belief? Can a person be a New Testament Christian and yet not subscribe to later creeds which most of traditional Christianity adopted? A question that continued to come up on both sides was, Just how much “bad theology” can the grace of God compensate for? Before too long, those kinds of issues became part of the dialogue itself, and in the process, the tension began to dissipate.

My LDS friends tell me that the initial feeling of formality has given way to a much more amiable informality, a true form of brother- and sisterhood, with a kindness in disagreement, a respect for opposing views, and a feeling of responsibility to truly understand (if not necessarily agree with) those not of his or her own faith—a responsibility to represent one’s doctrines and practices accurately and grasp those of others in the same way. In the words of Richard Mouw, the dialogues came to enjoy “convicted civility.”[1]

Realizing that the Latter-day Saints have quite a different hierarchal and organizational structure than the vast evangelical world, no official representative of the Church has participated in these talks, nor have there been any ecclesiastical overtones to them. Like you, we have no desire to compromise our doctrinal distinctiveness or forfeit the beliefs that make us who we are. We are eager, however, not to be misunderstood, not to be accused of beliefs we do not hold, and not to have our commitment to Christ and His gospel dismissed out of hand, to say nothing of being demonized in the process.

Furthermore, we are always looking for common ground and common partners in the hands-on work of the ministry. We would be eager to join hands with our friends in a united Christian effort to strengthen families and marriages, to demand more morality in media, to provide humane relief effort in times of natural disasters, to address the ever-present plight of the poor, and in more recent months, to guarantee the freedom of religion that will allow all of us to speak out on matters of Christian conscience regarding the social issues of our time.

In this latter regard, the day must never come that you and I or any other responsible cleric in this nation is forbidden to preach from his or her pulpit the doctrine we hold in our heart to be true. But in light of recent sociopolitical events and current legal challenges stemming from them, particularly regarding the sanctity of marriage, that day could come unless we act decisively in preventing it.[2] The larger and more united the Christian voice, the more likely we are to carry the day in these matters. In that regard we should remember the Savior’s warning against “a house divided against itself,” a house which finds it “cannot stand” against more united foes pursuing an often unholy agenda (see Luke 11:17).

Building on some of this past history and desirous that we not disagree where we don’t need to disagree, I wish to testify to you, our friends, of the Christ we revere and adore in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. We believe in the historical Jesus who walked the dusty paths of the Holy Land and declare that He is one and the same God as the divine Jehovah of the Old Testament. We declare Him to be both fully God in His divinity and fully human in His mortal experience, the Son who was a God and the God who was a Son; that He is, in the language of the Book of Mormon, “the Eternal God” (see Book of Mormon, title page). We testify He is one with the Father and the Holy Ghost, the Three being One: one in spirit, one in strength, one in purpose, one in voice, one in glory, one in will, one in goodness, and one in grace—one in every conceivable form and facet of unity except that of their separate physical embodiment (see 3 Nephi 11:36). We testify that Christ was born of His divine Father and a virgin mother, that from the age of twelve onward He was about His true Father’s business, that in doing so He lived a perfect, sinless life and thus provided a pattern for all who come unto Him for salvation.

In the course of that ministry, we bear witness of every sermon He ever gave, every prayer He ever uttered, every miracle He ever called down from heaven, and every redeeming act He ever performed. In this latter regard, we testify that in fulfilling the divine plan for our salvation, He took upon Himself all the sins, sorrows, and sicknesses of the world, bleeding at every pore in the anguish of it all, beginning in Gethsemane and dying upon the Cross of Calvary as a vicarious offering for those sins and sinners, including for each of us in this room.

Early in the Book of Mormon, a Nephite prophet “saw that [Jesus] was lifted up on the cross and slain for the sins of the world” (1 Nephi 11:33). Later, that same Lord affirmed: “Behold, I have given unto you my gospel, and this is the gospel which I have given unto you—that I came into the world to do the will of my Father, because my Father sent me. And my Father sent me that I might be lifted up upon the cross” (3 Nephi 27:13-14; compare D&C 76:40–42). Indeed, it is a gift of the Spirit “to know that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, and that he was crucified for the sins of the world” (D&C 46:13).

We declare that three days after the Crucifixion, He rose from the tomb in glorious immortality, the first fruits of the resurrection, thereby breaking the physical bands of death and the spiritual bonds of hell, providing an immortal future for both the body and the spirit, a future which can only be realized in its full glory and grandeur by accepting Him and His name as the only “name under heaven given among men, whereby we must be saved.” Neither is there nor can there ever be “salvation in any other” (Acts 4:12). We declare that He will come again to earth, this time in might, majesty and glory, to reign as King of Kings and Lord of Lords. This is the Christ whom we praise, in whose grace we trust implicitly and explicitly, and who is “the Shepherd and Bishop of [our] souls” (1 Peter 2:25).

Joseph Smith was once asked the question, “What are the fundamental principles of your religion?” He replied, “The fundamental principles of our religion are the testimony of the Apostles and Prophets, concerning Jesus Christ, that he died, was buried, and rose again the third day, and ascended into heaven; and all other things which pertain to our religion are only appendages to it.”[3]

As a rule, Latter-day Saints are known as an industrious group, a works-conscious people. For us, the works of righteousness, what we might call “dedicated discipleship,” are an unerring measure of the reality of our faith; we believe with James, the brother of Jesus, that true faith always manifests itself in faithfulness. We teach that those Puritans were closer to the truth than they realized when they expected a “godly walk” from those under covenant. Salvation and eternal life are free (see 2 Nephi 2:4); indeed, they are the greatest of all the gifts of God (see D&C 6:13; 14:7). Nevertheless, we teach that one must prepare to receive those gifts by declaring and demonstrating “faith in the Lord Jesus Christ”—by trusting in and relying upon “the merits, and mercy, and grace of the Holy Messiah,” a phrase taken from the Book of Mormon (2 Nephi 2:8; see also 31:19; Moroni 6:4). For us, the fruits of that faith include repentance, the receipt of gospel covenants and ordinances (including baptism), and a heart of gratitude that motivates us to deny ourselves of all ungodliness, to take up His cross daily (Luke 9:23), and to keep His commandments—all of His commandments (see John 14:15).We rejoice with the Apostle Paul: “Thanks be to God, [who] giveth us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Corinthians 15:57).

I hope this witness which I bear to you and to the world helps you understand something of the inexpressible love we feel for the Savior of the world in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Given our shared devotion to the Lord Jesus Christ and given the challenges we face in our society, to which I alluded earlier and which you are addressing so faithfully, surely we can find a way to unite in a national—or international—call to Christian conscience. Some years ago, Tim LaHaye wrote:

If religious Americans work together in the name of our mutually shared moral concerns, we just might succeed in re-establishing the civic moral standards that our forefathers thought were guaranteed by the Constitution. . . . I really believe that we are in a fierce battle for the very survival of our culture. . . . Obviously I am not suggesting joint evangelistic crusades with these religions; that would reflect an unacceptable theological compromise for all of us. [Nevertheless], all of our nation’s religious citizens need to develop a respect for other religious people and their beliefs. We need not accept their beliefs, but we can respect the people and realize that we have more in common with each other than we ever will with the secularizers of this country. It is time for all religiously committed citizens to unite against our common enemy.[4]

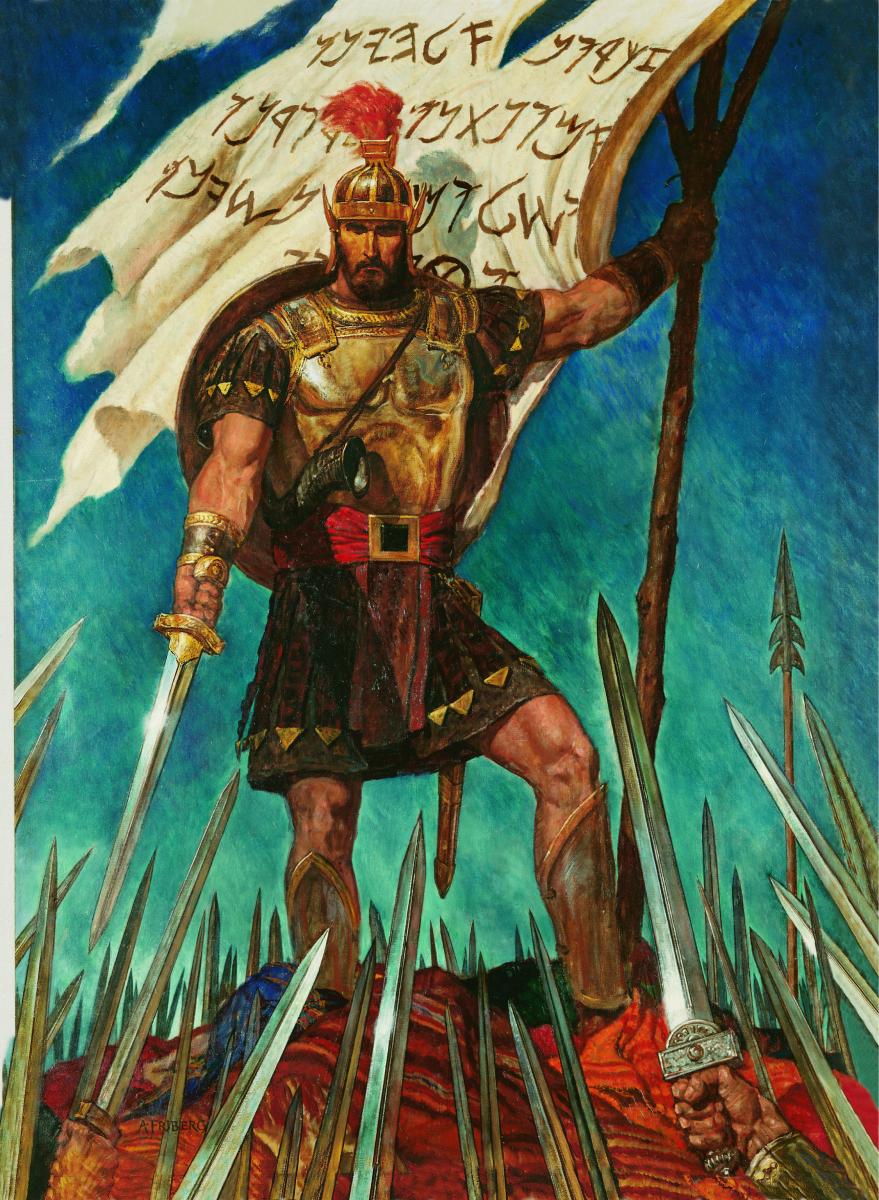

In Book of Mormon times, Captain Moroni rallied troops to fight for liberty by reminding them of their duty to God. Arnold Friberg, Captain Moroni and the Title of Liberty, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

In Book of Mormon times, Captain Moroni rallied troops to fight for liberty by reminding them of their duty to God. Arnold Friberg, Captain Moroni and the Title of Liberty, © Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

To be sure, there is a risk associated with learning something new about someone else. New insights always affect old perspectives, and thus some rethinking, rearranging, and restructuring of our worldviews are inevitable. When we look beyond a man or woman’s color or ethnic group or social circle or church or synagogue or mosque or creed or statement of belief, when we try our best to see them for who and what they are, children of the same God, something good and worthwhile happens within us, and we are thereby drawn into a closer union with that God who is the Father of us all.

In reflecting on his visit to Salt Lake City and his major message in our historic Tabernacle on Temple Square in November 2004, Ravi Zacharias observed:

The last time an evangelical Christian was invited to speak [in the Tabernacle] was 1899, when D. L. Moody spoke. . . . I accepted the invitation, . . . and I spoke on the exclusivity and sufficiency of Jesus Christ. I also asked if I could bring my own music, to which they also graciously agreed. So Michael Card joined us to share his music. He did a marvelous job, and one of the pieces he sang brought a predictable smile to all present. It was based on Peter’s visit to Cornelius’ home and was entitled, “I’m Not Supposed to Be Here.” He couldn’t have picked a better piece! I can truly say that I sensed the anointing of the Lord as I preached and still marvel that the event happened. The power of God’s presence, even amid some opposition, was something to experience. As the one closing the meeting said, “I don’t want this evening to end.” Only time will tell the true impact. Who knows what the future will bring? Our faith is foundationally and theologically very different from the Mormon faith, but maybe the Lord is doing something far beyond what we can see.[5]

Few things are more needed in this tense and confused world than Christian conviction, Christian compassion, and Christian understanding. Joseph Smith observed in 1843, less than a year before his death: “If I esteem mankind to be in error, shall I bear them down? No. I will lift them up, and in their own way too, if I cannot persuade them my way is better; and I will not seek to compel any man to believe as I do, only by the force of reasoning, for truth will cut its own way. Do you believe in Jesus Christ and the Gospel of salvation which he revealed? So do I. Christians should cease wrangling and contending with each other, and cultivate the principles of union and friendship in their midst; and they will do it before the millennium can be ushered in and Christ takes possession of His kingdom.”[6]

Thank you for your courteous invitation to me tonight. I close with this love for you, expressed by two valedictories in our scripture. First this from the Apostle Peter: “[May] the God of peace, that brought again from the dead our Lord Jesus, that great shepherd of the sheep, through the blood of the everlasting covenant, make you perfect in every good work to do his will, working in you that which is well pleasing in his sight, through Jesus Christ; to whom be glory for ever and ever. Amen” (Hebrews 13:20–21).

And this from the Book of Mormon, a father writing to his son: “Be faithful in Christ . . . [and] may [He] lift thee up, and may his sufferings and death . . . and his mercy and long-suffering, and the hope of his glory and of eternal life, rest in your mind forever. And may the grace of God the Father, whose throne is high in the heavens, and our Lord Jesus Christ, who sitteth on the right hand of his power, until all things shall become subject unto him, be, and abide with you forever. Amen” (Moroni 9:25–26).

Notes

[1] A term introduced in his book Uncommon Decency: Christian Civility in an Uncivil World (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1992).

[2] See the remarks of my fellow Apostle Elder Dallin H. Oaks at the Chapman University Law School, “Preserving Religious Freedom,” February 4, 2011, http://

[3] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1957), 3:30.

[4] Tim F. LaHaye, The Race for the 21st Century (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1986), 109.

[5] RZIM Newsletter 3 (Winter 2004): 2.

[6] Roberts, Comprehensive History of the Church, 5:498–99.