Catholic-Mormon Relations

Donald Westbrook

Donald Westbrook, "Catholic-Mormon Relations," Religious Educator 13, no. 1 (2012): 35–53.

Donald Westbrook (donald.westbrook@cgu.edu) was a doctoral student in the School of Religion at Claremont Graduate University when this was written.

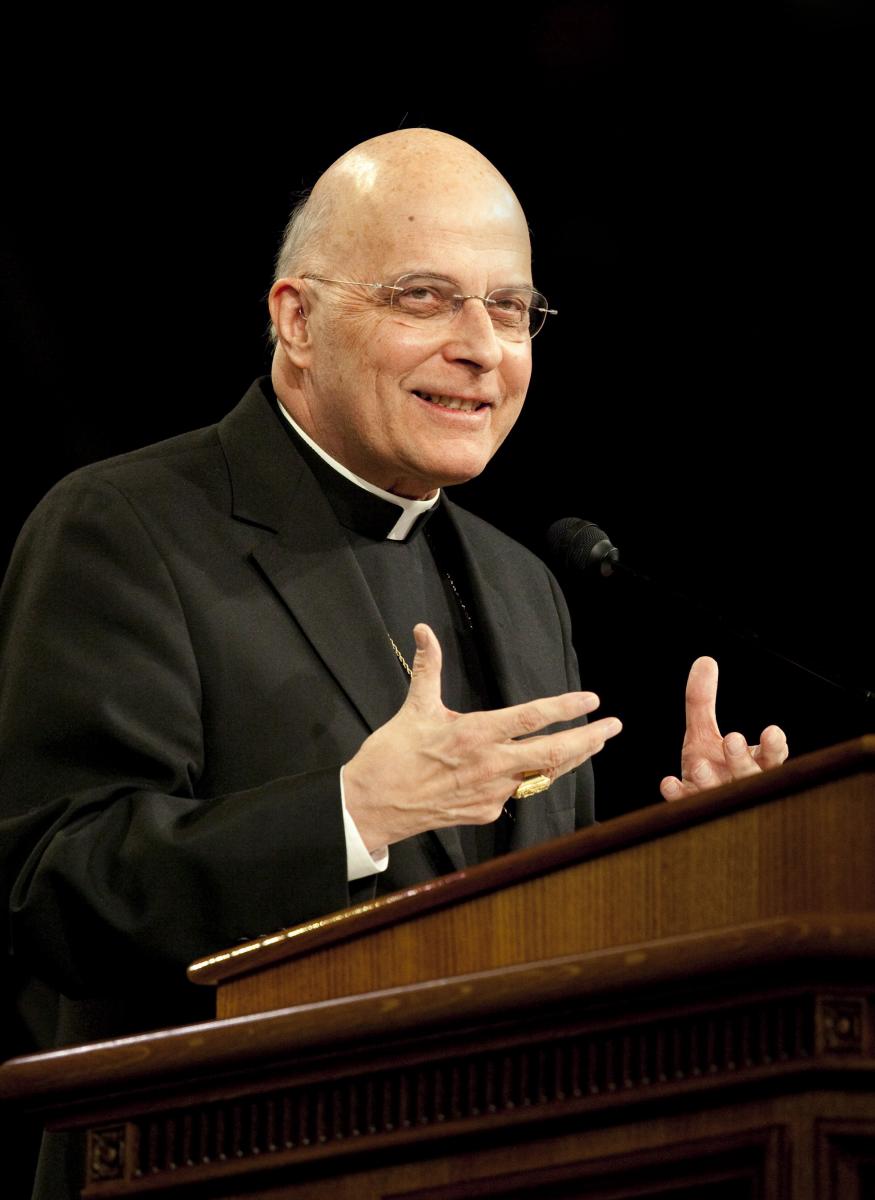

In 2010, Cardinal Francis George spoke at BYU on the topic of religious freedom and shared family values. Photo by Jaren Wilkey/

In 2010, Cardinal Francis George spoke at BYU on the topic of religious freedom and shared family values. Photo by Jaren Wilkey/

“The important thing is that we truly love each other, that we have an interior unity, that we draw as close together and collaborate as much as we can—while trying to work through the remaining areas of open questions. And it is important for us always to remember in all of this that we need God’s help, that we are incapable of doing this alone.”—Pope Benedict XVI[1]

“We labor diligently to write, to persuade our children, and also our brethren, to believe in Christ, and to be reconciled to God; for we know that it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do.”—2 Nephi 25:23

This essay very briefly introduces the reader to some of the problems and promises of relations between Catholics and Mormons in the American context. Exploration of the topic is worthwhile because relatively few Catholic and Mormon church leaders have explored it seriously, and even fewer academics and laypeople have addressed the matter in great depth.[2] The absence of substantive interfaith dialogue is all the more perplexing because Catholics and Mormons have recently come together in visible ways as partners in the defense of religious freedom. The passing in 2008 of California’s Proposition 8 was only the latest example of partnership between Catholics and Mormons (not to mention evangelicals) in a cause of shared moral concern. The essay attempts to remedy the lack of scholarly and interfaith attention to Catholic-Mormon relations by (1) evaluating the Catholic theological distinction between “ecumenical” and “interreligious” dialogue that might be a roadblock for Catholic ecclesiastical endorsement and participation, (2) presenting an introduction to Joseph Smith and Latter-day Saint restorationist theology intended for Catholics who are interested in Mormonism but do not know where to start learning about the religion, (3) offering an approach to Catholic-Mormon history and dialogue based on similarities and differences in each tradition’s worldview and “salvation history,” and (4) remarking on the future of Catholic-Mormon relations and dialogue. Ultimately, it is the goal of this essay to inspire interested Catholics and Mormons to come together for further reflection, clarification, conversation, engagement, and dialogue.

Background and the Ecumenical/

Before I proceed, some personal background might be helpful. As a Roman Catholic layperson, my motivation for exploring Catholic-Mormon relations is to encourage my Catholic brothers and sisters to take more seriously the history and belief system of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. At best, Catholics have a vague admiration of Mormons for their emphasis on the family and maintenance of wholesome and healthy lifestyles; at worst, they are suspicious of an odd belief system that they feel masquerades as Christian but is, in fact, a secretive cult. In order to better understand and appreciate our Mormon brothers and sisters and their worldview, it is imperative that Catholics learn more about Mormonism, preferably from Mormons themselves. This paper is the result of comparative historical and theological study, but it is first and foremost the product of my sustained conversations and dialogue with Latter-day Saint friends, colleagues, church leaders, and academics.

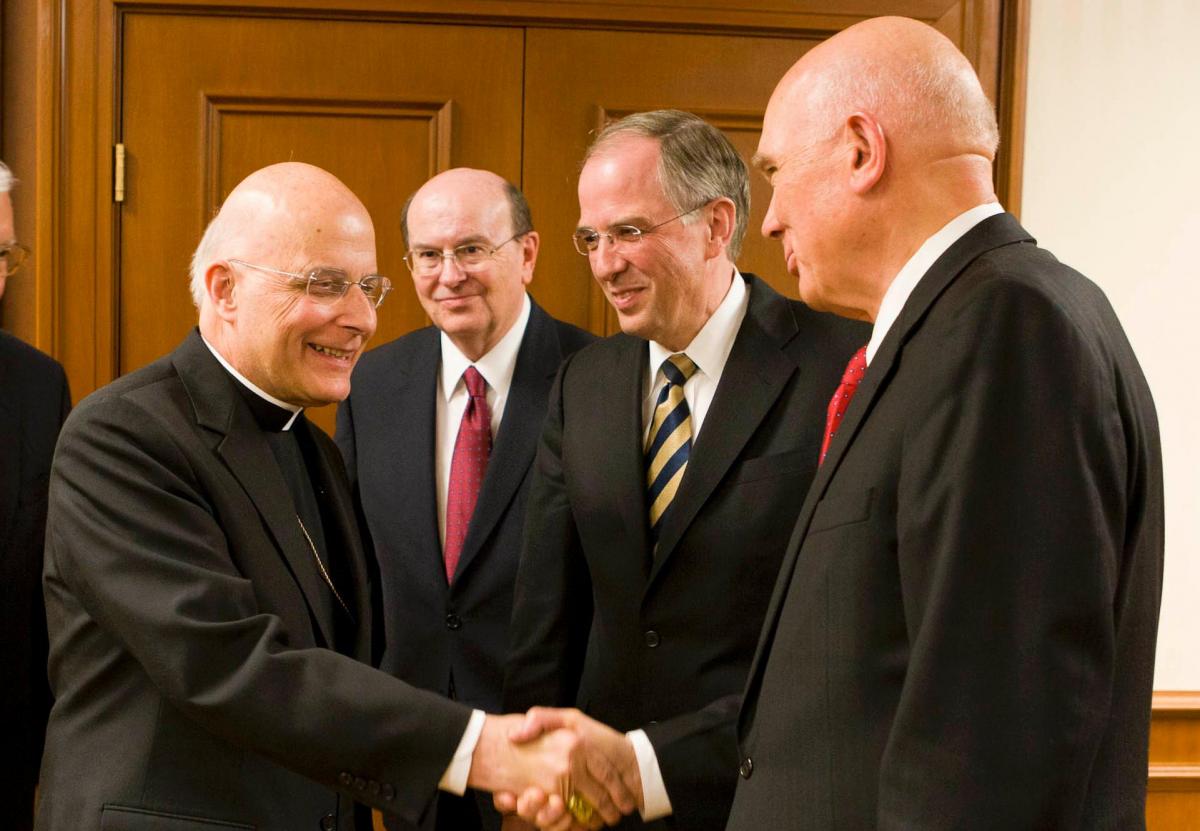

Encouragingly, interfaith relations between Catholics and Mormons seem to have improved in recent years. In February 2010, Cardinal Francis George, archbishop of Chicago and then president of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, spoke to a sympathetic audience at Brigham Young University on the topic of religious freedom and shared family values. The 2009 national convention of the Catholic Theological Society of America included a session entitled “Barriers and Bridges: The Challenges of Mormon-Catholic Dialogue.” Also in 2009, the Mormon Studies program at Claremont Graduate University sponsored a discussion on sacramental theology that featured Robert L. Millet of Brigham Young University and Father Alexei Smith of the Los Angeles Roman Catholic Archdiocese’s Office of Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs. These and other encouraging developments[3] signal what many Catholics and Mormons hope will lead to continued and substantive dialogue between our churches, in much the same way that evangelicals have extensively and fruitfully dialogued with Mormons in print, private meetings, and conferences.

However, it is disappointing that the US Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Secretariat for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs, which devotes itself to ecumenical and interreligious dialogue in the United States, has not commenced a substantive and ongoing dialogue with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I suspect this lack of formal and ongoing commitment is partly because the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity helps set the ecumenical and interreligious agenda for the worldwide church and the US Conference of Catholic Bishops designs programs and commissions to reflect this council’s broad global aims. On the other hand, it may simply be the case that Catholic authorities have been preoccupied with dialogue on other fronts and Mormons are not on their ecumenical radar. However, a deeper reason might be at work: the Catholic Church is still not sure what to make of the LDS Church on a theological level.

Questions that get tossed around include: Are Mormons Christian?[4] How should Catholic-Mormon dialogue progress given that the Catholic Church does not recognize Mormon baptisms? What do we do about the differences between Catholics and Mormons on doctrinal matters such as the Trinity and the nature of man’s relationship to the Triune God? If Catholics do engage in ongoing dialogue with Mormons, would that count as ecumenical or interreligious dialogue, or perhaps some nebulous area in between? Does Mormon doctrine provide enough theological common ground for a productive exchange or are we just too different theologically?

The Catholic distinction between ecumenical and interreligious dialogue, which is largely how the Catholic Church has categorized dialogue since the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), seems to present a simplistic and false theological distinction. The distinction is simplistic because it leaves out a number of religious groups, such as the Mormons, who clearly identify themselves as Christian yet are excluded from the ecumenical category because of theological commitments that put them outside mainstream Christianity. “Mainstream Christianity” here means a certain kind of Christianity—a creedalism in which particular doctrines are taken as standards of Christian orthodoxy. Classic examples include, but are not limited to, a commitment to the Nicene (325), the Nicene-Constantinopolitan (381), and the Chalcedonian Creeds (451) and a commitment to the canon of scripture as “closed” and limited to the Old and New Testaments. Since Mormonism falls outside these standards of theological orthodoxy with its open scriptural canon, rejection of the traditional creeds, and restorationist theology, Mormon-Catholic dialogue likely cannot properly be ecumenical given current Catholic (and for that matter, Protestant) parameters.[5] At the same time, Mormon-Catholic dialogue is clearly not interreligious either, because this would mean inaccurately lumping the Mormon Church with non-Christian religions such as Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sikhism.[6]

It would seem that dialogue between Catholics and Mormons is neither ecumenical nor interreligious. It occupies a nebulous and liminal space between the two categories and shares elements of both.[7] It is not ecumenical because that word has a history and specific meaning of ecclesial and/

As a Catholic, it is sometimes tempting to simply throw out or ignore the ecumenical-interreligious distinction if it is problematic or unhelpful in evaluating Catholic-Mormon relations. But like it or not, these are the categories that are largely in use in theological circles and that have embedded themselves in the interfaith vernacular. In the wake of the Second Vatican Council, Catholic archdioceses now have an Office of Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs, which compounds the problem of the sometimes false distinction. Rather than employ these categories or attempt to definitively settle the question of whether dialogue with Mormons counts as ecumenical or interreligious from the Catholic perspective, this paper opts instead to speak of worldviews and salvation history in the examples below. This approach seems more helpful, hopefully less abstruse, and uses a vocabulary that better frames and evaluates specific historical examples in a way that speaks to a broad spectrum of Catholics and Mormons.

When interfaith dialogue comes to mind, many people think of dialogue between academics and church leaders, but of course that represents merely one way of entering the conversation. Obviously dialogue does not have to take place at the level of Rome or Salt Lake City, or even at the level of dioceses and stakes, which is to say at the levels of traditional ecclesiastical authority. It can and should and does take place among ordinary, everyday people who self-identify as Catholic or Mormon (whether they be laypersons, church leaders, or academics) or who are simply interested in Catholicism and Mormonism, people who are mutually interested in learning from one another and about one another. The common denominators for participation in conversation and dialogue—however it is classified—should be trust, mutual respect, and cross-cultural appreciation rather than a position inside or outside an ecclesiastical hierarchy.

Joseph Smith and Latter-day Saint Restorationist Theology

It seems impossible to understand Catholic-Mormon relations, particularly for Catholics unfamiliar with the origins of Mormonism, without at least a cursory understanding of the person and mission of Joseph Smith Jr. In many ways, Joseph Smith was truly a product of his time. He lived from 1805 to 1844 during a period in American history known as the Second Great Awakening.[10] This was a time of intense religiosity—a time of divine visions, evangelical fervor, revivals, itinerant preachers, and competing churches vying for new members. The religiosity was so intense that Joseph Smith’s region of New York, Manchester and Palmyra, would later be called the “burned-over district” because it had been so thoroughly evangelized that there were few or no areas left unaffected by these zealous efforts.[11]

In this environment, Joseph Smith was confused. He was asking questions that presupposed the existence of objective Christian truth, but he was not sure where this truth was to be found. “In the midst of this war of words and tumult of opinions, I often said to myself: What is to be done? Who of all these parties are right; or, are they all wrong together? If any one of them be right, which is it, and how shall I know it?” (Joseph Smith—History 1:10). It is a testament to the intense religiosity of his time that Joseph Smith was wondering where this ultimate truth was or was not (as opposed to today, when many wonder if ultimate truth exists at all), and Smith seems to have been a genuine religious seeker overwhelmed by the competing voices of his day.

Since he was unsure about the religious environment surrounding him and, specifically, unsure which of the Protestant churches he should join, Joseph Smith decided to ask God. Around 1820, Joseph Smith went into the woods outside his farm near Manchester, New York, and prayed to God after reading James 1:5 (“If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given him”). According to Joseph Smith’s accounts, and today called the First Vision by Mormons, what followed was an experience in which God and Jesus visited Smith and told him that his sins were forgiven and that all the churches of his day were false.[12] Smith seems to have been mostly familiar with Protestant denominations in upstate New York, but he presumably understood this message from God to apply to all Christian traditions: they are impure, fundamentally untrue, false churches with false messages. As Joseph Smith recounted the divine event, “The Personage who addressed me said that all their creeds were an abomination in his sight; that those professors were all corrupt; that: ‘they draw near to me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me, they teach for doctrines the commandments of men, having a form of godliness, but they deny the power thereof’” (Joseph Smith—History 1:19).

What Smith set out to do during the rest of his life was to establish and lead the one true church on the earth as God’s prophets did in biblical times of old. The goal was nothing less than the restoration of that true and pure Christian church that had existed in New Testament times but was adulterated and gradually lost in the early history of Christianity (or, to put it differently, in the early history of the Catholic Church).[13] The church, initially called the Church of Christ, was founded on April 6, 1830, the same year the Book of Mormon was published. Doctrine and Covenants section 21, which was recorded on this inaugural date, provides something of a job description of Joseph Smith’s obviously preeminent role in the church: “Thou shalt be called a seer, a translator, a prophet, an apostle of Jesus Christ, an elder of the church through the will of God the Father, and the grace of your Lord Jesus Christ” (D&C 21:1). Though a twenty-five-year-old man with little formal education, he was clearly entrusted with the highest of ecclesial responsibilities.

Under Smith’s prophetic guidance, the Mormon Church restored ancient scripture, teachings, and institutions, including but not limited to the translation of the Book of Mormon (see D&C 3–5; 9; 16–17; 20), the restoration of the true priesthood (see D&C 2:1; 13; 84; 107; 124), the institutions of baptism (see D&C 22) and baptism for the dead (see D&C 128), the translation and reception of new scripture (works today known as the Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, and Pearl of Great Price), a retranslation of the Bible correcting errors that had crept in since New Testament times (see D&C 73),[14] covenants and ritual practices to be performed in temples (see D&C 127), knowledge about cosmology and the heavens (see D&C 76; 88; 131; 137), a restored understanding of the nature of God as physical,[15] and a literal and spiritual restoration of Zion itself (see D&C 97; 133).

For Smith, this was all made possible through continuing revelation—the idea that God spoke to him and through him as a modern prophet to lead the restored Church. Like other millennialists of the time, he thought the end of the world was near and attempted to build a community, indeed Zion itself, in anticipation of the Second Coming.[16] But Joseph Smith kept meeting resistance, and the Mormons were constantly displaced and persecuted—in New York, Ohio, Missouri, and finally Illinois, where he was assassinated by a mob in Carthage. The Mormon Church would continue under Brigham Young’s leadership, head west, and settle in what would become the Deseret Territory and later Utah; a splinter church would remain in the Midwest, becoming the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now the Community of Christ), which, beginning in 1860, was led by Joseph’s son, Joseph Smith III.[17]

Mormon-Catholic Relations in the United States: Salvation Histories Compared

As important as understanding Joseph Smith and Latter-day Saint restorationist theology is to the broader project of Catholic-Mormon relations, Catholics and Mormons did not interact very often during Joseph Smith’s lifetime. Smith’s message that the creeds of the churches of his day were an “abomination” surely applies to the Catholic Church just as much as it does to the Presbyterians, Methodists, Congregationalists, and others (if not more so given that the “early church” and Catholic Church are one and the same from the Catholic perspective), but most of Joseph’s interactions seem to have been with Christians of various Protestant backgrounds.

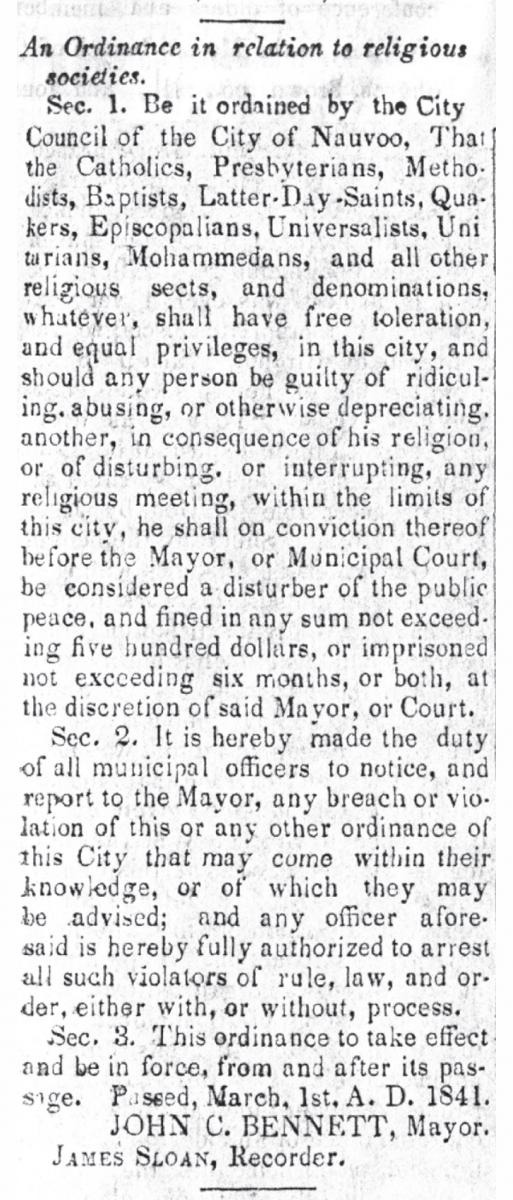

One notable exception came near the end of Joseph Smith’s life when, in 1841 in Nauvoo, Illinois, the city issued a decree on religious liberty that listed Catholics alongside a number of other groups, including Latter-day Saints themselves: “Be it ordained by the City Council of the City of Nauvoo, That the Catholics, Presbyterians, Methodists, Baptists, Latter-Day Saints, Quakers, Episcopalians, Universalists, Unitarians, Mohammedans, and all other religious sects, and denominations, whatever, shall have free toleration, and equal privileges, in this city.”[18] According to historian Richard L. Bushman, this welcome and pledge to religious groups in Nauvoo symbolized the sense all groups in the city would work toward the building of Zion.[19] In contrast to the exceptionalism that characterizes Mormon theology (to be addressed below), Joseph Smith took measures to ensure that the city would be a haven for those seeking freedom and toleration. After all, the Mormons founded Nauvoo, Illinois, because they were driven out of settlements in Missouri after military conflict and even an executive order to exterminate Mormons in that state (Missouri Executive Order 44). In Nauvoo, Joseph evidently had a vision that affairs would be different: “We claim no privilege but what we feel cheerfully disposed to share with our fellow citizens of every denomination.”[20]

Joseph Smith’s use of the phrase “fellow citizens” rather than “fellow Christians” seems significant. He sensed, despite different and competing religious systems and values, that religious groups and denominations came together as citizens in Nauvoo (and, of course, as citizens of the United States) who by that virtue were entitled to “free toleration” and “equal privileges.” In this sense, the Nauvoo ordinance brings to mind Cardinal Francis George’s 2010 address at Brigham Young University, entitled “Catholics and Latter-day Saints: Partners in the Defense of Religious Freedom.”[21] Cardinal George, who serves as archbishop of Chicago and was then president of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, remarked at the opening of his address: “I come before you today as a religious leader who shares with you a love for our own country but also, like many, with a growing concern about its moral health as a good society. . . . After 180 years of living mostly apart from one another, Catholics and Latter-day Saints have begun to see one another as trustworthy partners in the defense of shared moral principles and in the promotion of the common good of our beloved country.”

Nauvoo city ordinance announced in March 1, 1841, Times and Seasons.©2010 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Nauvoo city ordinance announced in March 1, 1841, Times and Seasons.©2010 Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved.

Elder Dallin H. Oaks (right) greets Cardinal Francis George during the Cardinal's visit to Salt Lake City as Elder Neil L. Andersen and Elder Quentin L. Cook look on.

Elder Dallin H. Oaks (right) greets Cardinal Francis George during the Cardinal's visit to Salt Lake City as Elder Neil L. Andersen and Elder Quentin L. Cook look on.

Cardinal George sensed in Provo in 2010 what Joseph Smith seemed to sense in Nauvoo in 1841: despite real and divisive differences in theology, Catholics and Mormons can and should come together as partners not only in the defense of religious liberty but also as partners in “shared moral principles” and “the promotion of the common good of our beloved country.” Another way of putting this might be that Mormons during the Nauvoo period—and Catholics in recent years—have sensed the extent to which both groups in America share and exercise religious freedom by virtue of common citizenship, despite competing worldviews and interpretations of salvation history.[22]

What are these worldviews? Consider, as an entry point, this comparison of Roman Catholic and Mormon salvation histories. Sketching salvation history is typically a theological exercise, but in the case of introducing Catholic-Mormon relations this comparison is helpful to highlight basic similarities and differences for Catholics and Mormons interested in joining together in conversation and dialogue.

Roman Catholic Salvation History | LDS/ |

|---|---|

| —— | Premortal existence |

| Creation | Creation |

| Fall (Negative) | Fall (Positive) |

| Redemption | Redemption |

| Apostolic authority | Apostolic authority |

| Apostolic succession | Great Apostasy |

| —— | Restoration/ |

| Eschaton | Eschaton |

Based on this representation, three differences immediately stand out on the Mormon side: (1) premortal existence, (2) belief that the fall of humanity in Eden was a positive event because it made mortal life possible (as opposed to the Catholic and Protestant view that humanity is tainted with original sin that requires Christ’s redemption), and, arguably most important in the broad comparison, (3) the loss of apostolic authority after the death of the first Apostles, which resulted in the Great Apostasy and required the restoration of ecclesiastical authority through Joseph Smith as prophet. Of course, there are many other differences between the Catholic and Mormon worldviews (for example, the Mormon belief that the redemption of Christ included blood agony in Gethsemane, differences about the details regarding the afterlife, Mormon temple practices, and the Mormon belief that God and humanity are of the same ontological species), but these three stand out for the purpose of a visual introduction.[23]

Arguably more revealing than the differences are the tremendous similarities and parallels, especially in terms of ecclesiology. Ecclesiastical authority is of utmost importance to both Catholics and Mormons. Where Mormons hold to an apostasy in the early church after the death of the Apostles, Catholics insist that apostolic authority has never been lost and persists to this day in the office of bishop, most visibly the bishop of Rome (who is the pope) and the governing body of the Magisterium.[24] This feature of Catholic ecclesiology is said to have foundation in the message of Jesus, who founded the church, to Peter, himself traditionally the first bishop of Rome: “And I say also unto thee, That thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. And I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” (Matthew 16:18–19). Where for Catholics there is continuity of authority, for Mormons there is a break in the chain, at least until Peter, James, and John restored divine authority to the earth in 1830.

Unlike many Protestant denominations that have reached out to one another in ecumenical unity, especially in the last hundred years, both the Roman Catholic Church and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have viewed themselves in largely exceptional terms.[25] Both lay claim to the “fulness of the gospel”[26] and true and divine ecclesiastical authority. In fact, it might be the case that the largest barrier for Catholic-Mormon relations and dialogue is that the Catholic Church and Mormon Church are far more similar than different, particularly ecclesiologically.

In the history of Catholic-Mormon relations in America, contention over the issue of authority has manifested itself on a number of occasions in ways that provide helpful commentary on this worldview difference. In 1958, Elder Bruce R. McConkie published his encyclopedic volume Mormon Doctrine, which infamously described the Catholic Church in the following way: “The Roman Catholic Church [is] specially—singled out, set apart, described, and designated as being ‘most abominable above all other churches.’”[27] This language was removed from subsequent editions, and President David O. McKay did not approve the volume’s publication.[28] However, in characterizing the Catholic Church this way, McConkie linked the language of abomination that is found in Joseph Smith’s First Vision and throughout Mormon scripture (see 1 Nephi 13:5–8; 14:10, 13–17; D&C 88:94; and, of course, Joseph Smith—History 1:19) as applying most clearly to the Catholic Church above all other churches.[29] To put it differently, of the churches most responsible for the Great Apostasy and for the loss of ecclesiastical authority, McConkie’s Mormon Doctrine implied that the Catholic Church deserves the most blame because of its alleged but false apostolic succession that stretched over two thousand years.

The Catholic bishop in Salt Lake City at the time of the publication of Mormon Doctrine, Duane Hunt, took notice of the volume. According to one report, the bishop, with tears in his eyes, said to a Mormon friend, “We are your friends. We don’t deserve this kind of treatment!”[30] The following year, 1959, saw the publication of Hunt’s own book, arguably a defensive work in Mormon-dominated Utah, in which he responded to the allegation of apostasy in early church history. Provocatively titled The Unbroken Chain (and subsequently published as The Continuity of the Catholic Church), it was Bishop Hunt’s attempt, as he wrote in the preface, “to point out to them that any break in the succession of the church organisation or in the teaching of the Gospel would have been and has proved to be impossible.”[31]

Again, of the differences in worldview summarized in the chart above, the issue of authority is arguably most divisive, so naturally the Mormon notion of a Great Apostasy would be offensive to Catholic leaders, especially for a bishop stationed in Salt Lake City. With such intense focus on the points of ecclesial disagreement, there seems to have been little space for the two churches to jointly explore theological similarities. “I am not in the least interested in any Mormon doctrine,” Bishop Hunt wrote evasively and dismissively, “except in so far as it is unfavorable to the Catholic Church. Then, to the best of my ability, I shall reply.”[32]

Unfortunately, Hunt’s response reflects the general attitude of Catholic ecclesial engagement with Mormon doctrine and theology that has taken place in recent years. At high ecclesiastical levels, Catholics seem by and large uninterested in theological engagement except in the form of a response to some ecclesial question or dispute. Rather than engage the Mormon worldview or salvation history, such responses have mostly been limited to reactions and proclamations aimed at clarifying the Catholic position with little if any elaboration. This has happened twice in the last decade and both times regarding the issue of baptism. The first was in 2001 when the Vatican issued a response to a dubium in which Mormon baptisms were declared invalid (thus requiring the rebaptism of Mormon converts to Catholicism).[33] The second came in 2008 when the Vatican directed Catholic dioceses worldwide not to provide records to the Genealogical Society of Utah, because of doctrinal disagreement over the practice of baptizing deceased Catholics in temples.[34] Both responses came from the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which exists to preserve and defend global Catholic orthodoxy.[35]

The Future of Catholic-Mormon Relations

Fortunately, relations between Catholics and Mormons seem to have improved, at least somewhat, since the contentious days of Elder McConkie and Bishop Hunt. Likely spurred on by the ecumenical efforts of Protestant brothers and sisters, the Second Vatican Council reoriented and modernized the Catholic Church on a number of fronts, including how Catholics view and understand other Christians and non-Christians.[36] Although the distinction between ecumenical and interreligious dialogue introduced earlier is arguably simplistic when evaluating Catholic-Mormon dialogue, the very existence of the distinction implies tremendous progress as the post–Vatican II church orients itself to traditions and theologies outside its own.

On the Mormon side, possibilities for interfaith relations have improved since the creation in 1973 of the Richard L. Evans Chair of Religious Understanding at Brigham Young University, which has been occupied by such luminaries as Truman Madsen, David Paulsen, Robert Millet, and presently James Faulconer, and has the goal of fostering “understanding among people of different faiths.”[37] Under Millet’s leadership, for example, Mormons and evangelicals came together in unprecedented ways, both public and private, especially through a dialogue relationship with Fuller Theological Seminary and that institution’s president, Richard Mouw.

But what is the future of Catholic-Mormon relations? However passive and reactive Catholic authorities can be in response to theological questions, there is little doubt that the Catholic Church has actively collaborated with Latter-day Saints on social, moral, and political causes. Catholic and Mormon support of Constitutional Amendment 2 in Hawaii (1998) and Proposition 20 (2000) and Proposition 8 (2008) in California were instrumental in the passage of state-level legislation defining marriage as a union between a man and a woman. In other words, there seems to be plenty of room for ecclesiastical-level engagement on shared values, but not so much on shared theologies. If worldview differences are any indication, this is not too surprising: it is far easier to join together on matters where there is moral and ethical agreement and little theological contention.

But what about Catholic-Mormon relations at the lay level? Here the opportunities for serious reflection, conversation, engagement, and dialogue are potentially more open-ended. Despite the apparent hesitance of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Secretariat on Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs to commence a substantive and ongoing dialogue between the Roman Catholic Church and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, there is no such limitation on individual Catholics to engage in interfaith relations as an extension of their calling and mission. One of the oft-neglected documents of the Second Vatican Council is the Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity (Apostolicam Actuositatem), which might have particular relevance for lay Catholics interested in dialoguing with Mormons.

While directed at lay Catholics, Apostolicam Actuositatem contains a simple but inspiring message applicable to both Catholics and Mormons as both traditions move forward: “Catholics should try to cooperate with all men and women of good will to promote whatever is true, whatever just, whatever holy, whatever lovable (cf. Phil. 4:8). They should hold discussions with them, excel them in prudence and courtesy, and initiate research on social and public practices which should be improved in line with the spirit of the Gospel.”[38] For laypersons, abstruse theological considerations often matter far less than the cultivation of trust, friendship, community, and love. However, until Catholic and Mormon ecclesiastical authorities commence a bilateral dialogue in the fashion of other such dialogues sponsored by the US Conference of Catholic Bishops,[39] it will be up to individual Catholics and Mormons to gather on their own and collaborate wherever possible. In so doing, these groups should find common ground and build community but never ignore the real theological differences between our traditions.

Notes

Many thanks to those who read and commented on early drafts of this essay, including Rachel Cope, Fr. James Massa, Sanjay Merchant, Robert Millet, Richard Mouw, Fr. Thomas Rausch, S.J., Jeffrey Roop, Fr. Alexei Smith, and Cory Willson. Most of all, deep thanks and appreciation to Richard Bushman, who was gracious enough to supervise an independent research project on this topic during the fall 2010 semester at Claremont Graduate University.

[1] Pope Benedict XVI and Peter Seewald, Light of the World: The Pope, The Church, and the Signs of the Times (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2010), 90. While Pope Benedict here speaks in particular of dialogue with Eastern Orthodox churches, the sentiment arguably applies to relations between Catholics and Mormons.

[2] Not surprisingly, scholarship on Catholic-Mormon relations focuses largely on the Utah context. See, for example: Gregory Prince and Wm. Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005), 112–23; and Gregory A. Prince and Gary Topping, “A Turbulent Coexistence: Duane Hunt, David O. McKay, and a Quarter-Century of Catholic-Mormon Relations,” in Journal of Mormon History 31, no. 1 (2005): 142–63. A useful history of the Catholic Church in Utah, even though it contains disappointingly little on relations with Mormons and the Mormon Church, is Bernice Maher Mooney and Msgr. J. Terrence Fitzgerald, Salt of the Earth: The History of the Catholic Church in Utah, 1776–2007, 3rd ed. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2008). One older sociological work is Robert Joseph Dwyer, The Gentile Comes to Utah: A Study in Religious and Social Conflict (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America, 1941), chapter 6.

[3] For example, Elders M. Russell Ballard and Quentin L. Cook participated in a papal prayer service during Pope Benedict XVI’s 2008 visit to St. Joseph’s Church in New York. Although not so recent, Catholic apologist Patrick Madrid dialogued/

[4] The weekly Jesuit magazine America featured an article on the future of Catholic ecumenical engagement that captured this point: “These involve evangelicals, Pentecostals and, as most recently, Mormons (acknowledging that their identity as Christians is disputed).” See Christopher Ruddy, “Our Ecumenical Future: How the Bishops Can Advance Christian Unity,” in America, November 8, 2010, 14–17.

[5] The word ecumenical is often used to characterize interfaith gatherings of all sorts, but rarely are its history and meaning very clearly understood. Most scholars would agree that the word, at least in modern times, has Protestant origins and a largely Protestant agenda. Catholics arguably reappropriated the concept at the Second Vatican Council, as most clearly seen in the council’s Decree on Ecumenism, Unitatis Redintegratio. The Protestant understanding of the term dates back (at least) to the Edinburgh Missionary Conference in 1910. Although Catholics and Protestants, not to mention the diversity of Catholicisms and Protestantisms, have different historical understandings of the word, neither camp would typically classify dialogue with Mormons as ecumenical, for many of the reasons above. For a good introduction to the dynamics of ecumenical and interreligious dialogue from the Catholic perspective, see Cardinal Edward Idris Cassidy, Ecumenism and Interreligious Dialogue: Unitatis Redintegratio and Nostra Aetate (New York: Paulist Press, 2005); Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2006); and Cardinal Francis Arinze, Meeting Other Believers: The Risks and Rewards of Interreligious Dialogue (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 1997).

[6] Although Catholics distinguish between ecumenical and interreligious dialogue, which arguably amount to dialogue with Christians and non-Christians, respectively, Vatican administration nuances the distinction in some instances. For example, dialogue with Jews (the Pontifical Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews) takes place under the administration of the ecumenical Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. On the other hand, dialogue with Muslims (the Pontifical Commission for Religious Relations with Muslims) takes place under the administration of the interreligious Pontifical Council for Interreligous Dialogue.

[7] In fact, it may very well be the case that Mormon-Catholic dialogue could form a case study for the larger purpose of reexamining the traditional Catholic distinction between ecumenical and interreligious. This goal is peripheral to the present one but should be taken up in the future by qualified Catholic ecumenists, historians, and systematic theologians.

[8] Richard John Neuhaus wrote in 2000 that relations with Mormons should count as interreligious, although he allowed that this classification might change over time with the development of nascent Mormon theology. As he put it: “One must again keep in mind that Mormonism is still very young. It is only now beginning to develop an intellectually serious theological tradition. Over the next century and more, those who are now the ‘dissidents and exiles’ may become the leaders in the forging, despite the formidable obstacles, a rapprochement with historic Christianity, at which point the dialogue could become ecumenical.” See Richard John Neuhaus, “Is Mormonism Christian? A Respected Advocate for Interreligious Cooperation Responds,” in First Things, March 2000, http://

[9] Obviously there are other reasons, in addition to self-identification, for recognizing Mormons as Christians. The central point here is not to make a deep theological statement about the nature of Christian identity. Rather, the aim is to problematize the Catholic ecumenical/

[10] One helpful introduction to the Second Great Awakening that accessibly situates it within the context of nineteenth-century American religious history is Nathan O. Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991).

[11] Thomas F. O’Dea, The Mormons (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957), 11. Joseph Smith gives us a glimpse of this scene: “Indeed, the whole district of country seemed affected by it” (Joseph Smith—History 1:5–9).

[12] The version most Mormons are familiar with comes from the first chapter of Joseph Smith—History, which is included in the Pearl of Great Price, specifically 1:11–20. See also Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Knopf, 2005), 38–40; and Grant H. Palmer, An Insider’s View of Mormon Origins (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002), 235–58.

[13] As Richard Bushman points out, the idea of restoration was not new or unique to the Mormons. Some believe that it was inherited in part from Walter Scott, a Baptist preacher who lived in Ohio around the same time as the Mormons. See Richard Lyman Bushman, Mormonism: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 4. The idea of restoration is absolutely essential to understanding the emergence of the LDS Church, and even Mormons today take great effort to make this known to a broad audience. Gary C. Lawrence, a pollster, marketer, and Mormon, recently expressed bewilderment that most Americans (86 percent by his poll) fail to understand that the concept of restoration is the Church’s “main claim,” despite extensive missionary work. See Gary C. Lawrence, How Americans View Mormonism: Seven Steps to Improve Our Image (Orange, CA: The Parameter Foundation, 2008), 42.

[14] Joseph Smith’s retranslation of portions of the Bible is referred to as the “Joseph Smith Translation,” a portion of which is found in the Pearl of Great Price as Joseph Smith—Matthew, and is referenced in the footnotes of the standard works of Mormon scripture.

[15] See the King Follett Discourse, given by Joseph Smith and reported by Willard Richards, Wilford Woodruff, Thomas Bullock, and William Clayton, as found in BYU’s Mormon Literature Sampler, and first published in Times and Seasons, August 15, 1844, 612–17; http://

[16] In Joseph Smith’s time, perhaps the closest millennialist counterpart was William Miller, who led the Millerites to their “Great Disappointment” on October 22, 1844, just a few months after Smith died. See David L. Rowe, God’s Strange Work: William Miller and the End of the World (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008).

[17] For more about the succession crisis after 1844, see Thomas F. O’Dea, The Mormons, 71, 188; Fawn M. Brodie, No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith, rev. ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 1971), 396–404; and Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 555–57.

[18] Cited in Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 416, and originally published in Times and Seasons, March 1, 1841, 336–37. Another exception came on June 16, 1844, when Joseph Smith, days before his death, mentioned Catholics in his Sermon in the Grove: “The old Catholic church traditions are worth more than all you have said. Here is a principle of logic that most men have no more sense than to adopt. I will illustrate it by an old apple tree. Here jumps off a branch and says, I am the true tree, and you are corrupt. If the whole tree is corrupt, are not its branches corrupt? If the Catholic religion is a false religion, how can any true religion come out of it? If the Catholic church is bad, how can any good thing come out of it? The character of the old churches have always been slandered by all apostates since the world began. I testify again, as the Lord lives, God never will acknowledge any traitors or apostates. Any man who will betray the Catholics will betray you; and if he will betray me, he will betray you. All men are liars who say they are of the true Church without the revelations of Jesus Christ and the Priesthood of Melchizedek, which is after the order of the Son of God.” See Joseph Smith, “Sermon in the Grove,” History of the Church, 6:473–79; Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, 369–76; and available online: http://

[19] See Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 415–16.

[20] Quoted in Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 416.

[21] A video recording of Cardinal George’s address is available online through BYU TV; http://

[22] This is not meant to imply any relationship between Catholic and Mormon theology and nationalism or American exceptionalism. However, discussion of religious liberty is one approach to enter the topic of relations between Catholics and Mormons in the American context, especially as it seems to have been understood by figures such as Joseph Smith and Cardinal George.

[23] For Catholics interested in a brief but substantive introduction to Mormonism, see Bushman, Mormonism: A Very Brief Introduction. Of course, there is abundant information available through The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints directly, online (www.lds.org and www.mormon.org) and, of course, through missionaries.

[24] For more about these aspects of Catholic ecclesiology, see Catechism of the Catholic Church (New York: Doubleday, 1994), particularly sections 874–96. For an excellent and accessible guide to this catechesis, see Compendium to the Catechism of the Catholic Church (Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2006). For a more sophisticated treatment of Catholic ecclesiology, especially post–Vatican II, see Thomas P. Rausch, S.J., Towards a Truly Catholic Church: An Ecclesiology for the Third Millennium (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2005).

[25] After the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic notion of extra Ecclesiam nulla salus (“outside the Church there is no salvation”) has been rearticulated and reformulated in recognition of traditions outside its own. See, for example, the Vatican II document Lumen Gentium, available through the Vatican’s online collection of Vatican II documents; http://

[26] “Fulness of the gospel” is a Latter-day Saint phrase from the Book of Mormon (see 1 Nephi 10:14; 13:24; 15:13; 3 Nephi 16:10), Doctrine and Covenants (see D&C 1:23; 14:10; 20:9; 35:17; 42:12; 90:11; 118:4; 133:57), and Joseph Smith—History 1:34. However, the idea arguably bears striking resemblance to the Catholic ecclesial notion of extra Ecclesiam nulla salus, even post–Vatican II. Also see the Catholic declaration Dominus Iesus, published in 2000 by the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith under the leadership of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI). Section 16 of this document helps clarify the language of “subsists in” which is found in Lumen Gentium through an understanding that churches outside the Catholic Church are categorized according to their doctrinal and ecclesiological communion with the mother church: “With the expression subsistit in [Latin for ‘subsists in’], the Second Vatican Council sought to harmonize two doctrinal statements: on the one hand, that the Church of Christ, despite the divisions which exist among Christians, continues to exist fully only in the Catholic Church, and on the other hand, that ‘outside of her structure, many elements can be found of sanctification and truth,’ that is, in those Churches and ecclesial communities which are not yet in full communion with the Catholic Church. But with respect to these, it needs to be stated that ‘they derive their efficacy from the very fullness of grace and truth entrusted to the Catholic Church’ (emphasis added). See Dominus Iesus, available on the Vatican’s website; http://

[27] McConkie even listed the instruction “See Church of the Devil” under the index entry for “Catholicism.” See Bruce R. McConkie, Mormon Doctrine, 1st ed. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1958), 108. Compare the 1966 edition and subsequent editions, which omit this language.

[28] According to Gregory Prince and Wm. Robert Wright, “McKay was infuriated when he found out about the book. Even before he saw it himself, he reacted to reports from his colleagues by instituting a policy (which remains in effect to this day) requiring advance approval from the First Presidency before any General Authority could publish a book.” See Prince and Wright, Rise of Modern Mormonism, 121–22.

[29] See Prince and Wright, Rise of Modern Mormonism, 122. As Prince and Wright put it, “In support of his allegation, he cited ‘great and abominable’ references from the Book of Mormon, even though the book does not make that connection itself.”

[30] Quoted in Prince and Wright, Rise of Modern Mormonism, 122. The friend was Congressman David S. King and the occasion was his 1958 election.

[31] Duane Hunt, preface to The Continuity of the Catholic Church (Wrexham, UK: Ecclesia Press, 1996), 7. A PDF copy of this book is available online (with permission from Ecclesia Press): http://

[32] Hunt, preface to Continuity of the Catholic Church, 7. For an excellent treatment of Bishop Hunt, as well as President McKay’s relationship with Catholicism and Catholics, see Prince and Topping, “Quarter-Century of Catholic-Mormon Relations,” 142–63.

[33] Of course, the LDS Church does not recognize outside baptisms at all (and thus requires the rebaptism of all converts), underscoring the exceptionalism of priesthood authority for Mormons. The Vatican did not provide a theological reason for not recognizing Mormon baptisms, although one explanation might be Catholic insistence on employing a Trinitarian formula during baptisms. For the Vatican’s official response to this dubium, published in 2001 by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith under the administration of Cardinal Joseph Ratinzger (now Pope Benedict XVI), see http://

[34] See Chaz Muth, “Vatican letter directs bishops to keep parish records from Mormons,” Catholic News Service, accessed 10 October 2010, http://

[35] In 2001 this office was run by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who in 2005 became Pope Benedict XVI.

[36] See the council’s Decree on Ecumenism Unitatis Redintegratio, and Declaration on Relations with Non-Christians Nostra Aetate, both available through the Vatican’s online collection of Vatican II documents; http://

[37] BYU Religious Education, http://

[38] Apostolicam Actuositatem (Chapter III, Section 10), available through the Vatican’s website; http://

[39] For a listing of present dialogue relationships, see the US Conference of Catholic Bishops’ website for the Secretariat for Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs; http://