The Design, Construction, and Role of the Salt Lake Temple

Richard O. Cowan

Richard O. Cowan, “The Design, Construction, and Role of the Salt Lake Temple,” in Salt Lake City: The Place Which God Prepared, ed. Scott C. Esplin and Kenneth L. Alford (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, Salt Lake City, 2011), 47–68.

Richard O. Cowan is a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University.

Within days of President Brigham Young’s arrival in the Salt Lake Valley in July 1847, he designated the site for the future temple. As he and a few others were walking across the area that one day would be Temple Square, he stopped between the two forks of City Creek, struck the ground with his cane, and declared, “Here will be the Temple of our God.” Wilford Woodruff placed a stake in the ground to mark the spot that would become the center of the future building. [1]

Building a Temple in the Desert

As early as December 23, 1847, an official circular letter from the Twelve invited the Saints to gather and bring precious metals and other materials “for the exaltation . . . of the living and the dead,” for the time had come to build the Lord’s house “upon the tops of the mountains.” [2] Soon afterward, President Young named Truman O. Angell Sr. as temple architect, a post he would hold until his death in 1887. His previous work as a wood joiner on both the Kirtland and Nauvoo Temples provided useful background for his new assignment. He would have an able assistant, William Ward, who received his architectural training in England and was skilled in stone construction. (Angell’s experience was primarily with wooden structures.) A skilled draftsman, Ward prepared drawings for the Salt Lake Temple under Angell’s direction. [3]

In 1852, men were put to work building a fourteen-foot wall of sandstone and adobe around the temple block. This not only provided security for the construction site but, like other projects sponsored by the Church's Public Works Department, also created worthwhile employment for men who otherwise would have been idle. [4]

At the general conference of October 1852, President Heber C. Kimball, first counselor in the First Presidency, asked the Saints whether they should build the temple of sandstone, of adobe, or of “the best stone we can find in these mountains.” The congregation unanimously voted that “we build a temple of the best materials that can be furnished in the mountains of North America, and that the Presidency dictate where the stone and other materials shall be obtained.” [5] In the mid-1850s, when deposits of granite were discovered in Little Cottonwood Canyon twenty miles southeast of Salt Lake City, President Young determined that the temple should be built of this material. Its permanence would be a fitting symbol of the eternal covenants to be entered into there.

The Salt Lake Temple site was dedicated on February 14, 1853. During the next several weeks, excavation for the temple proceeded. Cornerstones were laid on April 6, the twenty-third anniversary of the Church’s organization. Large stones, measuring approximately two by three by five feet, had been placed in convenient positions ahead of time. They were of firestone brought from Red Butte Canyon. [6]

On this beautiful spring day in the valley, general conference convened in the old adobe tabernacle on the southwest corner of the temple block. Accompanied by military honor guards and the music of three bands, a procession headed by Church leaders marched to the spot where the First Presidency and the Patriarch to the Church laid the southeast cornerstone. [7] President Young then spoke, explaining that the temple had to be built in order that the Lord “may have a place where he can lay his head, and not only spend a night or a day, but find a place of peace.” [8] The Presiding Bishopric, representing the lesser priesthood, laid the southwest cornerstone. The presidency of the high priests, the stake presidency, and the high council then placed the northwest cornerstone. Finally, the northeast cornerstone was laid by the Twelve and representatives of the seventies and the elders. The laying of each stone was accompanied by special music, speeches, and a prayer.

After a one-hour break, the conference resumed in the old tabernacle. Concerning the future temple, President Young declared:

I scarcely ever say much about revelations, or visions, but suffice it to say, five years ago last July [1847] I was here, and saw in the Spirit the Temple not ten feet from where we have laid the Chief Corner Stone. I have not inquired what kind of a Temple we should build. Why? Because it was represented before me. I have never looked upon that ground, but the vision of it was there. I see it as plainly as if it was in reality before me. Wait until it is done. I will say, however, that it will have six towers, to begin with, instead of one. Now do not any of you apostatize because it will have six towers, and Joseph only built one. It is easier for us to build sixteen, than it was for him to build one. The time will come when there will be one in the centre of Temples we shall build, and on the top, groves and fish ponds. But we shall not see them here, at present. [9]

Some temples built in the twentieth century, including Hawaii, Idaho Falls, Los Angeles, and Oakland, would fulfill elements of President Young’s prophecy. Even though the Conference Center across the street is not a temple, some have thought of its rooftop gardens as at least a partial fulfillment of this prophecy.

William Ward later described the source of the temple’s basic design: “Brigham Young drew upon a slate in the architect’s office a sketch, and said to Truman O. Angell: ‘There will be three towers on the east, representing the President and his two counselors; also three similar towers on the west representing the Presiding Bishop and his two counselors; the towers on the east the Melchisedek priesthood, those on the west the Aaronic preisthood. The center towers will be higher than those on the sides, and the west towers a little lower than those on the east end. The body of the building will be between these.’” [10]

Because the great temple would not be completed for forty years, temporary facilities needed to be provided where the Saints could receive temple blessings. During the pioneers’ early years in the Salt Lake Valley, these blessings had been given in various places, including the top of Ensign Peak and Brigham Young’s office. By 1852, endowments were being given in the Council House, located on the southwest corner of what are now South Temple and Main streets. This facility also accommodated a variety of other ecclesiastical and civic functions, so a separate place was needed where the sacred temple ordinances could be given. The Endowment House, a two-story adobe structure dedicated in 1855, was located in the northwest corner of Temple Square. It continued to bless the Saints until it was torn down in 1889 after other temples were finished in the region and as the Salt Lake Temple itself neared completion. [11]

Meanwhile, the Saints maintained their interest in constructing the temple. In the spring of 1856, Brigham Young sent Truman Angell on a special mission to Europe. Specifically, President Young instructed him to make sketches of important architectural works to become better qualified to continue his work on the temple and other buildings. [12]

On July 24, 1857, as the Latter-day Saints were celebrating the tenth anniversary of their entrance into Salt Lake Valley, they received the latest disturbing news that a potentially hostile United States army was approaching Utah. Not knowing the army’s intentions, Brigham Young had the temple foundation covered with dirt as a precaution. When the army arrived the following year, Temple Square looked like a freshly plowed field, and there was no visible evidence of the temple’s construction. As it turned out, the army marched through Salt Lake City without harming any property and set up its camp some thirty miles to the southwest, near Utah Lake. Even during the years when the army was in Utah, draftsmen in the architect’s office were busy planning the exact size and shape for each of the thousands of stones that would be needed for the temple. With the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, the army was needed elsewhere, and it departed from Utah by December of that year. The foundation was uncovered in preparation for work that would resume the following spring. [13]

At this time, President Young examined the newly uncovered foundation and became aware that it was defective. He and his associates noticed large cracks and concluded that its small stones held together with mortar could not carry the massive weight of the temple. [14] On January 1, 1862, he announced that the inadequate foundation would be removed and replaced by one made entirely of granite. The footings would be sixteen feet thick. “I want to see the Temple built in a manner that it will endure through the Millennium,” he later declared. [15] The work of rebuilding the foundation moved slowly, and the walls did not reach ground level until the end of the construction season in 1867, fourteen years after the original cornerstones had been laid.

Transporting the granite by wagon to Temple Square posed a major challenge to which the coming of the railroad provided a solution. When the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, a more efficient method of transportation became available. During the early 1870s, tracks of the Utah Southern (later part of the Union Pacific) pushed southward toward Utah Valley. Rather than following a direct route, they were swung to the southeast in order to pass closer to the temple quarry. (Over 125 years later, this exact route would be followed by the Trax light rail system.) A connection with downtown streetcar tracks provided direct access to Temple Square. Still, at the time of President Young’s death in 1877, the temple walls were only twenty feet high, just above the level of the first floor. Thus most of the temple’s construction was yet to be accomplished, even though twenty-four years of the forty-year building period had already passed. During the next few years, however, with the problems of transportation resolved, the pace would accelerate considerably.

Because the builders recalled President Young’s desire for this temple to stand through time, the structure was very solid. Even at their tops, the walls were six feet thick, and the granite blocks were individually and skillfully shaped to fit snugly together. Nearly a century later, Elder Mark E. Petersen attested to the soundness of the temple’s construction. He was in the temple when a rather severe earthquake hit, damaging several buildings around the Salt Lake Valley. “As I sat there in that temple I could feel the sway of the quake and that the whole building groaned.” Afterward, he recalled, the engineers “could not find one semblance of damage” anywhere in the temple. [16]

Before his death in 1868, President Heber C. Kimball had prophesied that “when the walls reached the square, the powers of evil would rage and the Saints would suffer persecution.” [17] This point was reached in 1885, when the main walls of the temple, excluding the towers, were completed.

This was a time of bitter anti-Mormon persecution, and Temple Square was temporarily confiscated by hostile government officials. Thus the stage was set for the anti-Mormon crusade that raged during the 1880s. The Saints’ enemies boasted that the Mormons would never be allowed to finish the temple but that the “Gentiles” would complete the building for their own purposes. [18] Following the abandonment of plural marriage, relationships between Mormons and Gentiles improved. Confiscated properties were returned, and Utah finally became a state in 1896.

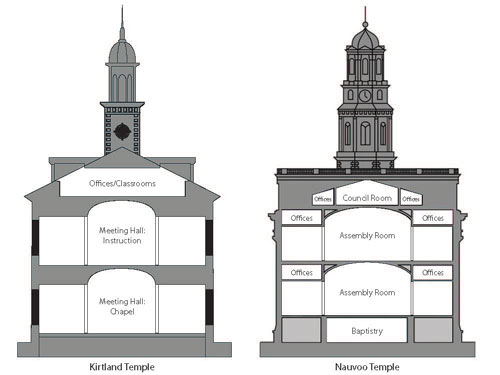

Fig. 1. Cross sections of the Kirtland and Nauvoo temples. (Image previously published in Temples to Dot the Earth [Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 1997]. Used with permission.)

Fig. 1. Cross sections of the Kirtland and Nauvoo temples. (Image previously published in Temples to Dot the Earth [Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 1997]. Used with permission.)

The Temple’s Interior

The temple’s exterior walls were nearing completion in the mid-1880s when the architects proposed significant changes for the yet-unconstructed interior. The original plan called for the Salt Lake Temple to follow the basic pattern of earlier temples. The Kirtland Temple had consisted primarily of two large assembly rooms, one above the other. The Nauvoo Temple expanded on this plan by adding a row of small rooms along each side of the elliptical ceiling of the two main auditoriums (see fig. 1). The large rooms were illuminated by tall windows, while the small side rooms had round windows. This pattern reflected the pattern used in the Nauvoo Temple.

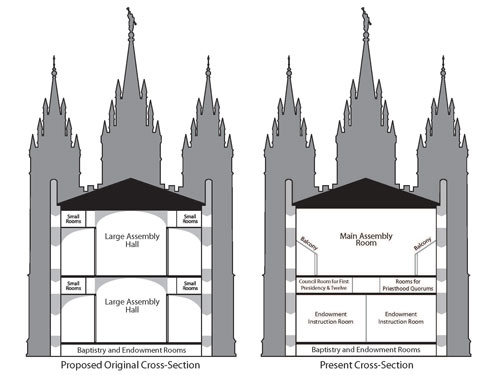

With the dedication of the Logan Temple in 1884, Truman O. Angell Jr. turned his attention to assisting his elderly father in completing drawings for the Salt Lake Temple. Early the following year, he proposed that rather than having two large assembly rooms with elliptical ceilings, as had been the case in Nauvoo, the Salt Lake Temple should follow the pattern that Presidents Young and John Taylor had already approved for Logan and Manti. There would be only one assembly room (on the upper floor) and it would have balconies under the elliptical windows along each side. The temple’s main floor would contain spacious rooms for presenting the endowment, while an intermediate floor would provide smaller council rooms for the use of various priesthood groups (see fig. 2). This plan would accommodate three hundred persons in the endowment sessions—more than twice the number that could be served in the basement under the original arrangement. These changes were consistent with President Young’s 1860 instructions that the temple would not be designed for general meetings, but rather it would “be for the endowments—for the organization and instruction of the Priesthood.” [19] Thus the design of the Salt Lake Temple reflected the Saints’ unfolding understanding of temple functions.

Truman O. Angell Sr., however, urged President Taylor to finish the temple according to the original plans. No final decision was made before President Taylor’s death in July of 1887. Although the general features of the younger Angell’s proposal were eventually adopted, none of his plans were followed exactly. The final plans for the temple appear to have been drawn under President Wilford Woodruff’s direction by Joseph Don Carlos Young, who became Church architect in 1890—just three years before the temple’s completion. [20] It is evident, therefore, that most of the work on the temple’s interior must have been accomplished during only these last few years of construction.

Some have suggested that in the Salt Lake Temple, shafts were provided for elevators and spaces left throughout the building for electric conduits and heating ducts even before these technologies were known. Angell Sr., however, certainly would have learned about elevators, which were just coming into use at the time of his 1856 visit to Europe. By the early 1860s, electricity was already being used in Utah for the Deseret Telegraph system. Hence, most of the temple’s interior was designed and built long after these technologies emerged. Although the west center tower proved to be a convenient location for the two main elevators, there is no evidence to suggest that their shafts were planned when there was no knowledge of this technology. [21]

Fig. 2. Cross sections of the Salt Lake Temple showing the original and final designs of the temple's interior. (Image previously published in Temples to Dot the Earth. Used with permission.)

Fig. 2. Cross sections of the Salt Lake Temple showing the original and final designs of the temple's interior. (Image previously published in Temples to Dot the Earth. Used with permission.)

Symbolism of the Temple’s Exterior

As had been the case in ancient times, the temple’s physical arrangement was calculated to teach important lessons. The intent of the temple’s design, one architectural historian observed, was “to aid man in his quest to gain entrance back into the presence of God from whence he came.” [22]

As with the Nauvoo Temple, special ornamental stones were an important feature of the Salt Lake Temple’s exterior. An earthstone formed the base of each of the temple’s fifty buttresses. These were the largest stones in the temple, weighing over six thousand pounds and having on their face a representation of the globe, four feet in diameter. These stones served as a reminder, architect Angell explained, that the gospel message had to go to all the earth. [23] Each buttress had a moonstone about halfway up, and a sunstone near its top. Because the earth is presently in a telestial condition, the three ornamental stones on each buttress might represent the three degrees of glory in ascending order—telestial, terrestrial, and celestial. These, together with the starstones on the temple’s towers, also reminded Latter-day Saints of these kingdoms. One scholar has suggested another possible interpretation. Referring to Abraham 3:5, he pointed out that “as we move upward into the heavens, the time sequences become longer. Likewise, the temple stones that communicate time begin with a short period of time, the day, and move toward the eternal present, where time almost ceases to move.” The earthstones at the temple’s base represent our planet, which rotates once every day. Stones about halfway up the building depict the moon’s monthly cycle. Sunstones near the top symbolize yet a longer period of time—the year. The depiction of stars even higher on the building suggests yet longer periods of revolution. [24]

The constellation of Ursa Major (the Big Dipper), depicted on the west center tower, is positioned so that the two “pointer stars” at the end of the dipper are literally aligned with Polaris (the North Star) in the heavens. This star appears to be a fixed point in the sky around which other stars revolve; hence, it might be thought of as representing eternity, or the absence of time. Angell suggested another message to be gained from this constellation on the temple—“the lost may find themselves by the Priesthood.” [25] In more recent years, President Harold B. Lee referred to this statement in conjunction with the introduction of family home evenings and other priesthood-centered programs, and likened it to the increasingly important role being given to the priesthood. [26]

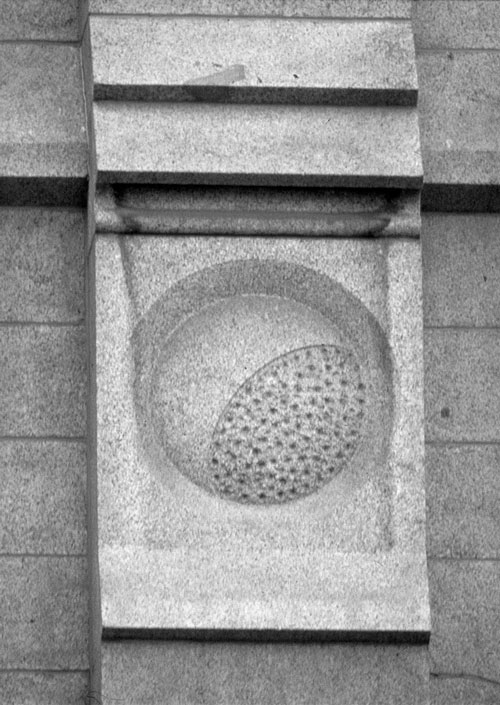

Fig. 3. Architectural detail on the exterior of the Salt Lake Temple showing a moon motif. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Fig. 3. Architectural detail on the exterior of the Salt Lake Temple showing a moon motif. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

An interesting feature on the moonstones is often overlooked. Proceeding from right to left, they successively represent the moon’s new, first-quarter, full, and third-quarter phases. Since the fifty buttresses cannot be divided evenly by these four phases, “the specific reason for fifty moon-stones,” one student of the Salt Lake Temple’s architecture has concluded, “was to create a sequential break to establish the beginning point of the lunar cycle.” [27] This break occurs on the north wall. If the date of January 1 is assigned to the new moon immediately after this break, dates can also be assigned to each of the succeeding phases. The right buttress on the face of the temple’s main east center tower would thus represent April 6, regarded by some Latter-day Saints as the date of the Savior’s birth. [28] Gilded letters on this same tower identify April 6 as the date of the temple’s commencement and completion (see fig. 3). [29] The left buttress on this tower includes a representation of the full moon. Because Easter is celebrated on the Sunday following the first full moon after the beginning of spring, this moonstone may remind us of the Savior’s atoning sacrifice, which was completed with his Resurrection on that first glorious Easter morning. A plan of the temple drafted in 1878 carefully plotted each moon stone according to lunar phase and month of year. [30]

The buttresses of the east center tower also include cloudstones, which show rays of sunlight penetrating through the clouds. These are representations of the gospel light piercing the dark clouds of superstition and error (see Isaiah 60:2–3). They also recall how a cloud of glory filled the ancient temple (see 1 Kings 8:10) and will rest upon the latter-day temple in the New Jerusalem (see D&C 84:5). On the same tower, the keystone at the top of the lower large window depicts clasped hands. These are reminders of the power that comes from brotherly love and fellowship and of the unity that must exist among those who would build Zion (see Galatians 2:9; Moses 7:18; D&C 38:24–27; 88:133). The hands also suggest the importance of honoring sacred commitments. President Gordon B. Hinckley declared that the temple is “a house of covenants. Here we promise, solemnly and sacredly, to live the gospel of Jesus Christ in its finest expression. We covenant with God our Eternal Father to live those principles which are the bedrock of all true religion.” [31] The keystone above the east center tower’s upper window depicts God’s “all-seeing eye” which watches over both the righteous and the wicked (see 1 Kings 9:3; Psalm 33:13–14, 18–19; Proverbs 15:3). [32]

The Angel Moroni

On April 6, 1892, as a band played “The Capstone March,” the Saints gathered south of the temple. An estimated forty thousand crowded into Temple Square, while an additional ten thousand filled the surrounding streets or watched from windows and the roofs of adjacent buildings. To that date, this was the largest group of Saints to meet in one place. Promptly at high noon, President Wilford Woodruff stepped to the podium, raised “both hands to heaven,” and proclaimed in a loud voice: “Attention, all ye house of Israel and all ye nations of the earth. We will now lay the top stone of the Temple of our God.” [33] The official capstone was the upper half of the round ball atop the east center spire. It had been hollowed out to accommodate scriptures, selected books, and other historical mementos, including music, coins, photographs, and “a polished brass plaque inscribed with historical information.” [34] President Woodruff pressed a button on the stand, and an electrically operated device lowered the capstone slowly and securely. As the stone descended into place, Elder Lorenzo Snow led the Hosanna Shout, with thousands of white handkerchiefs waving in unison. From high up on the temple, architect Joseph Don Carlos Young called out that the capstone was duly laid. With great emotion, the huge throng sang “The Spirit of God.” [35]

Later that afternoon the statue of the angel Moroni was hoisted to its position on top of the capstone. The twelve-and-a-half-foot, hammered-copper figure had been prepared in Salem, Ohio, from a model by Utah sculptor Cyrus E. Dallin. Even though Dallin was not a Latter-day Saint, he later professed, “My ‘Angel Moroni’ brought me nearer to God than anything I ever did. It seemed to me that I came to know what it means to commune with angels from heaven.” [36] Unveiled at a ceremony at 3:00 p.m., its gold-leafed surface gleamed in the sun. The statue depicted a heavenly herald sounding his trumpet, representing the latter-day fulfillment of John’s prophecy of an angel bringing “the everlasting gospel to preach unto them that dwell on the earth, and to every nation, and kindred, and tongue, and people” (Revelation 14:6).

Not all temples have had statues of Moroni. Only one of the Church’s previous five temples had an angel on its tower. The Nauvoo Temple featured a weathervane depicting an angel flying in a prone position. This was a common decoration on churches of the time, so whether or not it was specifically intended to represent Moroni is a matter of conjecture. Thus the Salt Lake Temple was the first to include the familiar vertical figure, which eventually would become a well-known feature of Latter-day Saint temples.

By 1980, the Church would dedicate fourteen more temples, with only the two largest—Los Angeles and Washington D.C.—having the familiar herald angel on their towers. Since that time, even smaller temples have included statues of Moroni. Other artists have sculpted these statues, and interestingly, the angel on the Atlanta Temple was a smaller replica of Cyrus Dallin’s original Moroni. Many, but not all, of these angels face east, suggesting their watching for and heralding the Second Coming of Christ which has been compared to the dawning of a new day (see Joseph Smith—Matthew 1:26).

The Temple Completed and Dedicated

At the capstone-laying ceremonies on April 6, 1892, Elder Francis M. Lyman of the Quorum of the Twelve issued a challenge to the vast multitude of Saints assembled for the occasion. He spoke of President Woodruff’s desire and dream to live long enough to dedicate the temple. [37] Lyman proposed a resolution that those present pledge to provide the funds necessary to complete the building so that it might be dedicated just one year later—the fortieth anniversary of the cornerstone laying. This proposition was adopted unanimously. [38]

When this goal was set, most believed that the remaining work would take at least three more years. In fact, as late as March 1893, many still wondered if the temple could be finished by the following month. Nevertheless, those working on the temple made a special effort to complete the project on time. [39]

The temple was completed and ready for dedication by noon on April 5, 1893, just a few hours ahead of the deadline. Between three and five o’clock that afternoon, the temple was opened for the visit of prominent community leaders and members of other faiths. Some six hundred responded to the invitation, including the clergy, business leaders, federal officials, and their families. They were permitted to pass through every room in the temple from the basement to the roof and to examine any portion of the interior they desired. Qualified guides escorted them and answered their questions. Many expressed appreciation to the Church for this hospitable gesture. This inaugurated the custom of conducting a public open house prior to temple dedications. [40]

At last the long-anticipated day was at hand—the dedication of the great temple at Salt Lake City following a forty-year period of construction. [41] Of those who had helped lay the cornerstone in 1853, only a few were still living. The temple’s original architect, Truman O. Angell, had died in 1887. The supervising architect at the time of dedication, Joseph Don Carlos Young, had been born in 1855, two years after construction had begun. [42] During this period, more than a generation had passed away.

The first dedicatory session was on Thursday morning, April 6, 1893. “A terrible storm arose that day. Rain fell in torrents, and the wind blew with savage fury. It was as if the forces of evil were lashing out in violent protest against this act of consecration,” President Hinckley reflected a century later. “But all was peace and quiet within the thick granite walls.” [43]

The temple’s dedication was a spiritual highlight for those who attended. In the initial session, the dedicatory prayer was offered by President Woodruff, followed by the unique Hosanna Shout, led by President Snow. Thirty-one dedicatory sessions continued over the next three weeks. They were held in the large upper assembly room, which could accommodate about 2,250 persons, and included the dedicatory prayer and Hosanna Shout. As the choirs sang the “Hosanna Anthem,” composed by Evan Stephens especially for this occasion, the congregation joined at the appropriate point with the traditional singing of “The Spirit of God.”

Later Reconstruction of Adjacent Facilities

An annex stood about one hundred feet north of the temple proper. Designed by Joseph Don Carlos Young, its architecture was described as Byzantine or Moorish. It was built of cream-colored oolite stone from the Manti quarry. Thus the architecture and material of the annex were different from the temple itself. Construction on this facility started in 1892, and it was dedicated the following year at the same time as the temple itself. The annex included a large entry area where patrons presented their temple recommends and where the recorder noted and distributed names of persons for whom ordinances were to be performed. It also included an assembly room seating three hundred, where meetings were held for those preparing to enter the temple. [44]

Seven decades later, this structure was razed to make way for a new annex. In August 1962, the Salt Lake Temple closed. A temporary annex was constructed in the nearly completed North Visitors’ Center, and beginning in March 1963 patrons could access the temple via an underground passage while construction on the new facilities moved forward. These included a new addition on the north side of the temple which provided several new sealing rooms. The new temple annex, entered through a doorway in the north wall of Temple Square, included a four hundred-seat chapel, subterranean dressing rooms with four thousand lockers, and large waiting rooms for those attending temple marriages. Both the annex and the addition were faced with granite from the original canyon quarry and were designed to match the architecture of the temple. [45] These new facilities, which opened in March 1966, greatly expanded the temple’s capacity. On October 22, 1967, after the North Visitors’ Center had gone into service, the new facilities were dedicated by President Hugh B. Brown in a service attended by General Authorities and temple workers.

The Temple’s Continuing Key Role

The Salt Lake Temple as well as the angelic figure atop its highest tower are two of the most widely recognized iconic symbols of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Additionally, for the Church itself, marvelous spiritual experiences have been linked with this temple over the years. Perhaps the most outstanding example was the appearance of the Savior to President Snow in the large corridor just outside the celestial room. President Snow later described what happened: “It was right here that the Lord Jesus Christ appeared to me at the time of the death of President Woodruff. He instructed me to go right ahead and reorganize the First Presidency of the Church at once and not wait as had been done after the death of the previous presidents, and that I was to succeed President Woodruff. . . . He stood right here, about three feet above the floor. It looked as though He stood on a plate of solid gold.” [46]

For many years (until the Missionary Training Center was established in Provo), this temple was where most outgoing missionaries received their endowment as part of their weeklong orientation. A disproportionately large number of Church members have chosen this temple for their eternal marriages. For example, in contrast to the roughly 5 percent of Churchwide endowments for the dead that were performed in Salt Lake during the early 1990s, 15 percent of all celestial marriages were performed there. [47]

Because of its location at Church headquarters, the Salt Lake Temple plays a unique and significant role in Church governance. Key decisions are reached following prayerful consideration by the Council of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, who meet weekly in their council room within the temple. These decisions include such matters as ordaining and setting apart new Presidents of the Church, appointing other General Authorities, creating new missions and stakes, and approving Church programs. Notable examples have included the 1952 decision to build temples overseas, the determination in 1976 to add what we now know as sections 137 and 138 to the standard works, and the 1978 revelation extending the priesthood to all worthy males (Official Declaration 2). Reflecting on these weekly meetings in the temple, Elder Spencer W. Kimball affirmed that those who could witness the prophet’s wisdom in reaching decisions would surely believe he was inspired. “To hear him conclude important new developments with such solemn expressions as ‘the Lord is pleased’; ‘that move is right’; ‘our Heavenly Father has spoken,’ is to know positively.” [48] Thus the Salt Lake Temple not only teaches gospel truths through its richly symbolic exterior and provides saving ordinances for the living and the dead, but also continues to play a key part as God’s kingdom rolls forth to fill the whole earth.

Daytime view of the south side of the Salt Lake Temple. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Daytime view of the south side of the Salt Lake Temple. (© Intellectual Reserve, Inc.)

Notes

[1] Matthias F. Cowley, Wilford Woodruff: History of His Life and Labors (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1964), 619–20; B. H. Roberts, Comprehensive History of the Church, 6 vols. (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1965), 3:279–80. After reviewing various diary entries, Randall Dixon believes that this event took place on July 26, 1847 (statement to the author, May 6, 2010).

[2] James R. Clark, comp., Messages of the First Presidency (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965), 1:333.

[3] C. Mark Hamilton, The Salt Lake Temple: A Monument to a People (Salt Lake City: University Services, 1983), 51–53.

[4] Arnold K. Garr, Richard O. Cowan, and Donald Q. Cannon, eds., Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 966–67.

[5] Heber C. Kimball, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854), 1:160, 162.

[6] Firestone was a variety of sandstone found in the mountains adjacent to Temple Square. Although it was used widely in buildings, it was prone to cracking because its porous nature allowed water to permeate the rock and freeze. Therefore, it was not as suitable as granite to support a large building such as the temple.

[7] The office of Patriarch to the Church was included among the General Authorities until 1978. See Daniel H. Ludlow, ed., Encyclopedia of Mormonism (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 3:1065–66.

[8] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 2:33; James H. Anderson, “The Salt Lake Temple,” Contributor, April 1893, 252–59.

[9] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 1:133.

[10] “Who Designed the Temple?” Deseret News Weekly, April 23, 1892, 578.

[11] The demolition of the Endowment House also served as a visible signal that the Church was serious about ending plural marriages. In his 1890 “Manifesto,” President Wilford Woodruff declared that because a plural marriage was alleged to have been performed there, “the Endowment House was, by my instructions, taken down without delay.” Doctrine and Covenants Official Declaration 1.

[12] Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Every Stone a Sermon (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1992), 17; see also Marvin E. Smith, “The Builder,” Improvement Era, October 1942, 630.

[13] Manuscript History of Brigham Young, December 18, 1861, 49, in W. A. Raynor, The Everlasting Spires: The Story of the Salt Lake Temple (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1965), 102.

[14] Raynor, Everlasting Spires, 101–3; see also Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1833–1898, Typescript, ed. Scott G. Kenney (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1984), 5:399.

[15] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 10:254; see also Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 6:71.

[16] Mark E. Petersen, Priesthood Genealogical Research Seminar (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1974), 510, quoted in Richard O. Cowan, Temples to Dot the Earth (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 1997), 102–3.

[17] Orson F. Whitney, Life of Heber C. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1967), 397.

[18] James H. Anderson, “The Salt Lake Temple,” Contributor, April 1893, 269–70. Concerning the seizure of Temple Square, see Joseph Fielding Smith, Essentials in Church History (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1979), 489.

[19] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses 8:203.

[20] Truman O. Angell Jr. to John Taylor, April 28, 1885, and Truman O. Angell Sr., to Taylor, March 11, 1885, in Hamilton, Salt Lake Temple,54–57.

[21] Paul C. Richards, “The Salt Lake Temple Infrastructure: Studying It Out in Their Minds,” BYU Studies 36, no. 2 (1996–97), 212–18.

[22] Hamilton, Salt Lake Temple, 147.

[23] Truman O. Angell Sr., “A Descriptive Statement of the Temple Now Being Erected in Salt Lake City. . . .” Millennial Star, May 5, 1874, 273–75.

[24] Richard G. Oman, “Exterior Symbolism of the Salt Lake Temple: Reflecting the Faith that Called the Place into Being,” BYU Studies 36, no. 4 (1996–97), 4:32–34.

[25] Angell, “The Temple,” Deseret News, August 17, 1854, 2.

[26] Harold B. Lee, in Conference Report, October 1964, 86.

[27] Hamilton, Salt Lake Temple, 143.

[28] Recent scholarship has suggested other possible dates for the Savior’s birth. See, for example, Jeffrey R. Chadwick, “Dating the Birth of Jesus Christ,” BYU Studies 49, no. 4 (2010): 5–38.

[29] Hamilton, Salt Lake Temple, 142–43.

[30] Hamilton, Salt Lake Temple, 142.

[31] Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Salt Lake Temple,” Ensign, March 1993, 6.

[32] Duncan M. McAllister, Description of the Great Temple (Salt Lake City: Bureau of Information, 1912), 7–10; Anderson, “Salt Lake Temple,” 276.

[33] Deseret Weekly News, April 9, 1892, 516.

[34] Matthew B. Brown and Paul Thomas Smith, Symbols in Stone: Symbolism on the Early Temples of the Restoration (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 1997), 127. Unfortunately, when the capstone was opened in 1993 many of the items it contained had been destroyed because of exposure to moisture.

[35] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 9:192–94 (April 6, 1892); compare James E. Talmage, House of the Lord (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1962), 149–52.

[36] Cyrus Dallin, in Levi Edgar Young, “The Angel Moroni and Cyrus Dallin,” Improvement Era, April 1953, 234.

[37] Matthias F. Cowley, Wilford Woodruff: History of His Life and Labors (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1964), 562.

[38] Anderson, “Salt Lake Temple,” 274.

[39] Anderson, “Salt Lake Temple,” 283.

[40] McAllister, “Temples of the Latter-day Saints: Purposes for Which They Are Erected,” Liahona, February 22, 1927, 417; John R. Winder, “Temples and Temple Work,” Young Woman’s Journal, February 1903, 51.

[41] For a description of these events, see Holzapfel, Every Stone a Sermon, especially chapter 9.

[42] Anderson, “Salt Lake Temple,” 279.

[43] Gordon B. Hinckley, in Conference Report, April 1993, 92.

[44] Hamilton, Salt Lake Temple, 182.

[45] Arnold J. Irvine, “Temporary Annex Ready For Use,” Church News, March 16, 1963, 8–9; George L. Scott, “New S. L. Temple Annex Opens,” Church News, March 19, 1966, 7–11.

[46] LeRoi C. Snow, “An Experience of My Father’s,” Improvement Era, September 1933, 677, 679.

[47] Based on temple ordinance statistics in author’s possession.

[48] Spencer W. Kimball, “. . . To His Servants the Prophets,” Instructor, August 1960, 257.