Mormonism and American Religious Art

Jane Dillenberger

Jane Dillenberger, “Mormonism and American Religious Art” in Reflections on Mormonism: Judaeo-Christian Parallels, ed. Truman G. Madsen (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1978), 187–200.

Jane Dillenberger, art historian and critic whose expertise is focused on religious art in America, included in one of her San Francisco exhibits seven paintings of C. C. A. Christensen, a Mormon artist whose canvases had been more or less unknown for several decades. In her present essay (which includes some illustrative reproductions) she raises both historical and aesthetic questions. For example: How much of Mormon attitudes toward art, toward, for example, Florentine architecture or Christian statuary, arose from the vision of a new revelatory encounter with the Divine, and how much derived from the attitudes which converts brought with them into the Church? Much of modern revelation reenthrones the glory and dignity and transforming role of the sensuous-artistic. Yet some Mormon art has lagged behind that renewing insight. And the Mormons generally have been significantly suspicious of “arty” approaches to life and of appeals to the aesthetic which somehow seek to separate it from sanctity to offer it as a substitute for religious living.

Holding to high standards of classical art, Professor Dillenberger finds in Christensen and some other Mormon artists a passion and insight and joy that overcomes limitations of skill and method. And she contrasts such paintings with the “illustrative” kind of art which has sometimes been dubbed “World’s Fair Mormonism.”

The question follows (and was raised following the presentation of her paper) whether it is appropriate to speak of Mormon art or of artistic Mormons. She inclines toward the second position. She urged that in the end, as with truth so with beauty, “nothing praiseworthy or lovely” can properly fall outside the Mormon perspective or its educational outreach. Her implicit thesis is that religious art, illustrative or not, becomes merely decorative in proportion to the superficializing of religious feeling. Depth, strength of conviction, and dedication are prerequisites of lasting religious art. Here she is at one with the vision of the highest in the Mormon legacy.

T. G. M.

In an address, “The Arts and the Spirit of the Lord” (given at BYU on February 1, 1976), Elder Boyd K. Packer tells how, as chairman of a group responsible for producing a filmstrip on Church history, he discovered a large roll of canvases painted by one of his progenitors, C. C. A. Christensen (1831–1912). Elder Packer’s committee sent a truck down to Sanpete County to recover the paintings, and when the massive roll of canvases was opened out, the Mormon story was visible from the Giving of the Golden Leaves to Joseph Smith to the Arrival in the Great Salt Lake Basin when Brigham Young declared “This is the place.”

In the 1890s, C. C. A. Christensen had used his own paintings to accompany a lecture on Church history when he traveled through Western settlements telling the Mormon story. As each episode was recounted, the corresponding painting would be unrolled and displayed by lamplight. Thus C. C. A. had done for his generation of Mormons what Elder Packer’s committee of seminary men intended to do for their own generation. But it is certain that the discovery of the Christensen paintings meant for the outside world the discovery of Mormon art. The paintings were exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1970 and reproduced in color in Art in America, a significant nationally known periodical. And seven of the paintings were included in a large traveling exhibition in 1972, “The Hand and the Spirit: Religious Art in America 1700–1900.”

The twenty-two paintings, done on heavy linen, each 8 feet by 10 feet, were originally sewn together so that they could be turned by a crank, and the audience thus viewed the paintings, episode by episode, as the artist told their story. When the roll of paintings was recovered the individual paintings were separated, conserved, and framed. It was in this form that they have been seen subsequently.

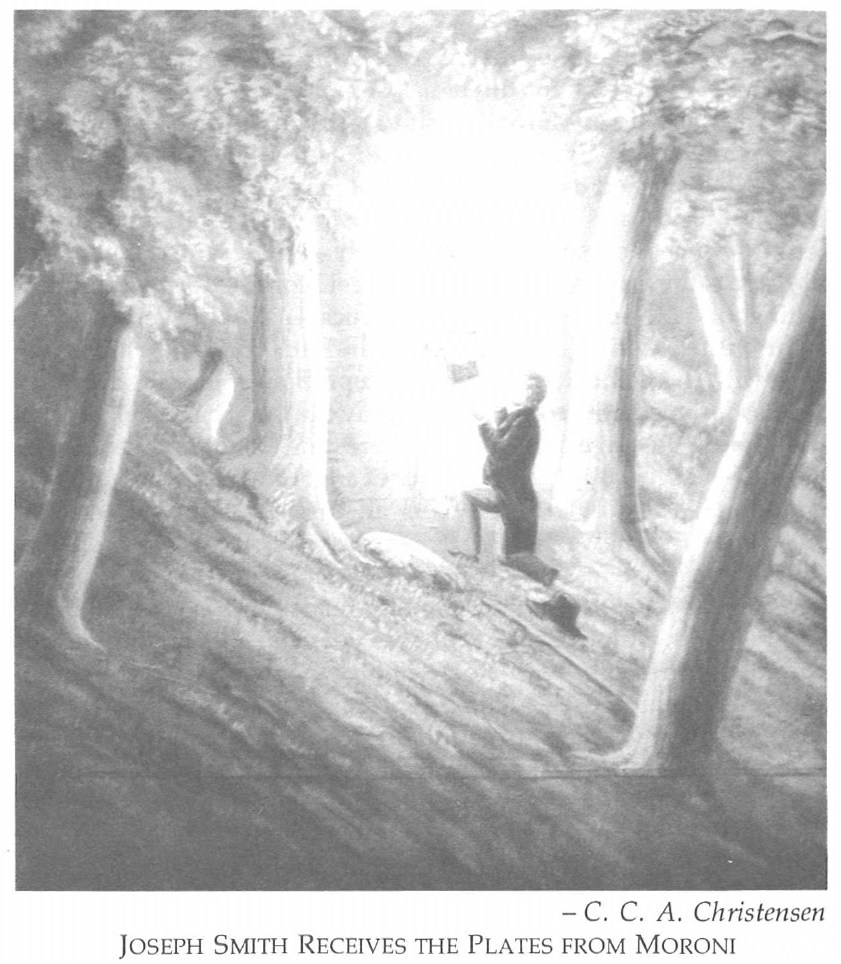

The first painting has the descriptive label: “In 1827, when Joseph Smith, the future Mormon Prophet, was 21 years old, an angel named Moroni, who had appeared to him several times before, delivered a book of golden pages to him with a strict charge, to translate the contents of the book—which he translated, as the ‘Book of Mormon’—for the benefit of all living.”

The painting of Moroni’s visit to Joseph Smith has a poetry of conception which gives the event depicted a kind of verity. The artist has distanced us from the miraculous encounter. The steeply sloping hillside and diagonal trees provide a charming woodland setting, which is cursorily—even naively—represented. But not at all naive is the artist’s placing of the angel Moroni, deep within this setting, his body entirely and quietly vertical—the only vertical form in the entire painting. A nimbus surrounds his body as he holds the book with the golden pages before Joseph Smith. Joseph, dressed, in all propriety, in the frock coat and gray trousers, has fallen on one knee before the angel Moroni. An interesting iconographic detail is the fully bearded angel. The absence of angel’s wings is not unusual iconographically, but the beard is an unusual attribute. And it underlines the inevitable parallelism between this event and the biblical event of Moses receiving the tablets of the Law.

The label for the second painting reads: “In late March 1832, near Kirtland, Ohio, Joseph Smith was sleeping, after having stayed up most of the night with a sick child, when about a dozen men burst into the room, seized him and dragged him into a field. There they tore off his clothes, beat and scratched him, and covered his bruised body with hot tar and feathers; nevertheless he appeared at church the following day and calmly preached without mention of the attack he had endured the previous evening.”

As one studies this scene of the mobbing of Joseph Smith, it is obvious that Christensen did not have the ability to represent the human body in movement with any sense of accuracy and organic unity. Yet the awkwardness of the individual figures is offset by Christensen’s instinct for effectively grouping the figures, thus conveying the sense of impending violence. Contrasted with the procession of evildoers is the setting of nature: the full moon glimpsed through a rift in the clouds illumines the clearing, a few barren trees, and the distant darkened dwellings.

The description of the third painting in the series reads:

“Gentiles [the Mormon name for non-Mormons] burned barns, tore down cabins, destroyed crops and attacked Mormon families with extreme violence. Nonetheless the Mormons clung to their beliefs with tenacity and fought back with dogged determination. Some of their neighbors expressed great bitterness against them, and a hostile folk-lore began to assert itself. Mormon-haters resented the Mormon way of life and the Mormon claim that Joseph Smith was a true Prophet of the Lord.”

Christensen may have seen in Europe or at the Academy in Copenhagen a painting of the Massacre of the Innocents. The postures of several of the female figures in Christensen’s painting of the Missouri persecution suggest those in Raphael’s, Rubens’s and Breughel’s paintings of the theme. Christensen has therefore drawn upon this ancient biblical theme of brutality and attempted genocide in his rendering of the persecution of the Mormons. A parallelism between the New Testament episode and Mormon persecution may have been in the artist’s mind.

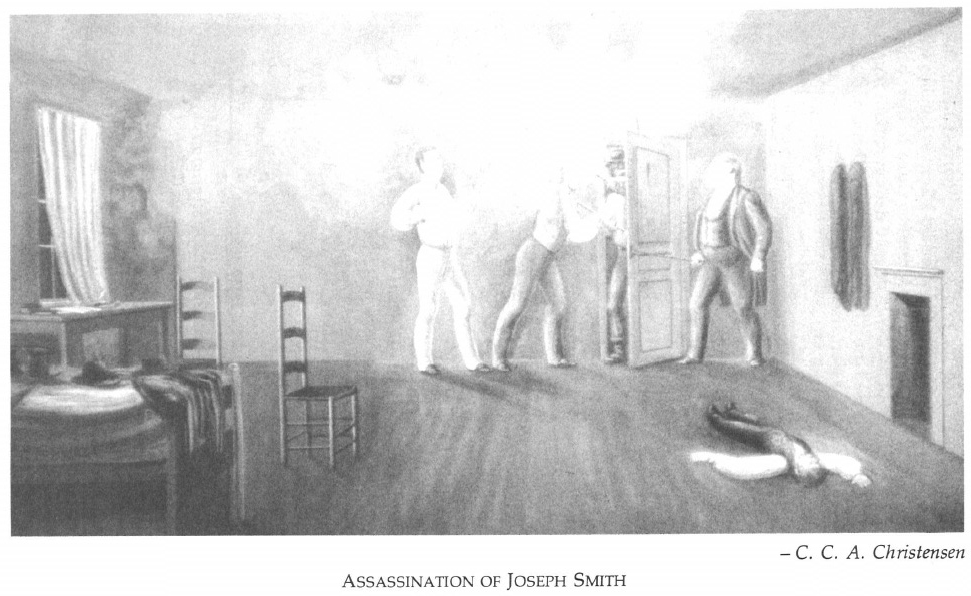

Despite the faulty draftsmanship of the figures in the next painting, this picture of the assassination of Joseph Smith is the most powerful single painting in the group. Joseph Smith, dressed entirely in white as befits the hero, the martyr, and the Saint, is at the center of the composition, deep in the space of the echoingly empty room. The narrow range of color kept within the grays, browns, and blacks, except for a red coat on the narrow bed, all accentuate the whiteness of the martyr. Beneath the scene in bold letters on a black background is the stark declaration, “The Blood of the Martyrs is the Seed of the Church.”

“Arrested on a charge of treason in June 1844, Joseph and his brother Hyrum, and two fellow Mormons, were confined in the second story of a jail in Carthage, Illinois, to await trial. Promises had been given that the Carthage Grays, a local militia company, would protect the prisoners. Instead, they turned against the men, stormed the jail and, despite a spirited defense, murdered Joseph and his brother. The killings occurred on the afternoon of June 27th, and messengers were sent to spread the news.”

The next painting is described in these words:

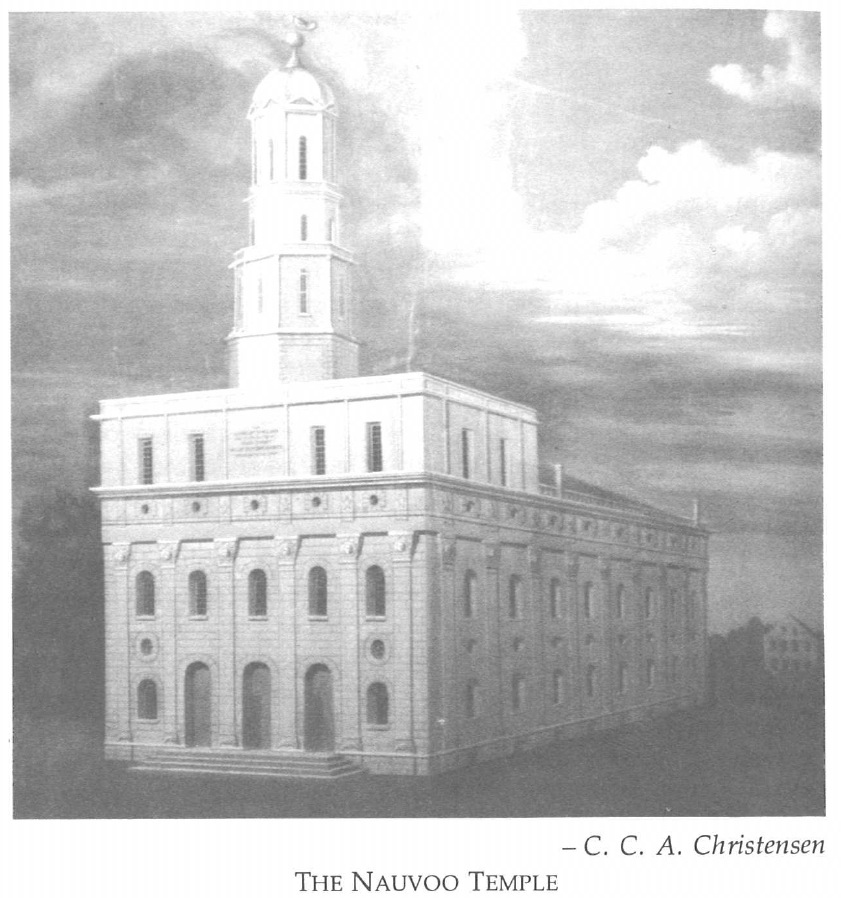

“The Nauvoo Temple was almost completed at the time Joseph Smith was murdered. It stood on the crest of the highest bluff in the center of the city, and the gleaming angel at the top of the spire could be seen for miles across the Illinois countryside. In 1844—the year of the Prophet’s death—Nauvoo was said to have 20,000 inhabitants, a population larger than that of Chicago at that same time. The Mormons’ homes, businesses and farms contributed to the city’s prosperity.”

This is an extraordinarily effective painting of the Nauvoo Temple. With the structure placed on barren ground without bush or tree, enclosure or sidewalk, the great temple seems an apparition rather than a structure built by human hands. No persons, no dogs, no carriage or cart, inhabits the surrounding quiet space.

The Mormons began the famous Nauvoo Temple in 1841. It measured 128 feet east and west, 88 feet north and south, and 60 feet above the ground level to the eaves. The spire rose an additional 98 feet. Native gray limestone from local quarries was used for the walls. For more than five years the Mormons labored, and at its completion the temple was the largest and most widely known structure north of St. Louis and west of Cincinnati.

Something of the massive size of the building can be gleaned by seeing an extant capital for the building. This stone is more than 4 feet in height and about 51/

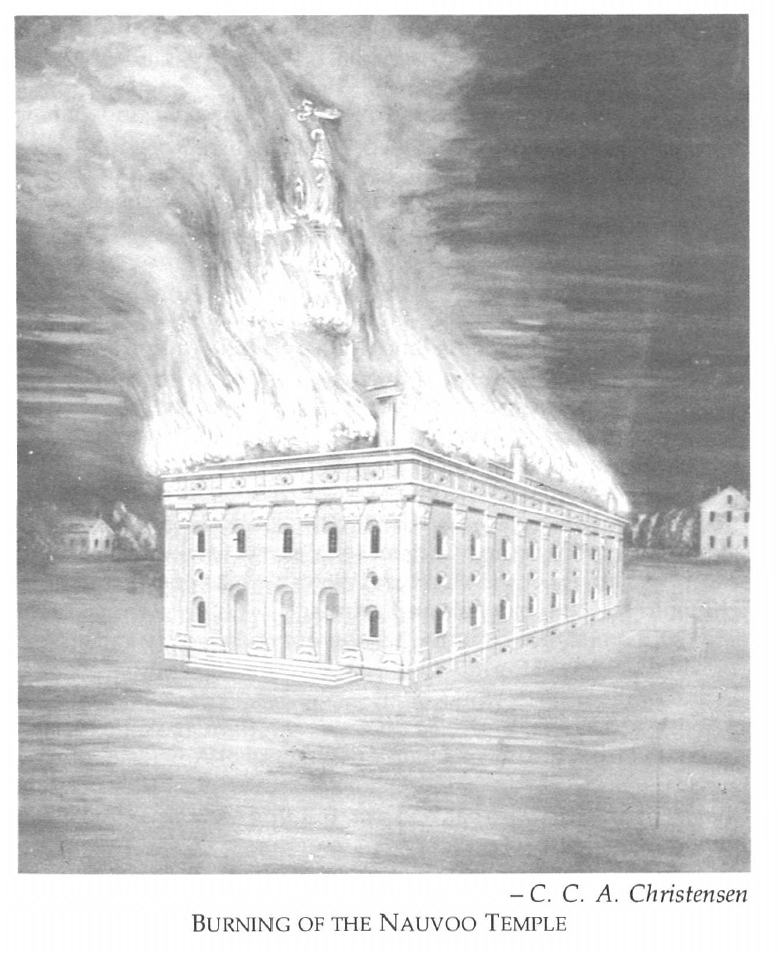

The Burning of the Nauvoo Temple is another striking painting and shares with the preceding panel a surrealism of form and effect.

“On the night of October 9, 1848 [actually November 19, 1848], a Mormon-hating arsonist raced in darkness through the upper floors of the Nauvoo Temple. About three o’clock in the morning of October 10th, flames burst suddenly from the tall spire, enveloping the gleaming angel, and those Mormons who were still in the vicinity, saw their temple burn to the ground. Flames leaping high into the clear October sky were visible from great distances.”

We come now to the departure from Nauvoo.

“Disheartened, the people had planned to move from Nauvoo in the spring, but persecutions became so violent that their first wagon team for the almost unknown west crossed the Mississippi River on February 4, 1846. By February 15, the weather had become so bitterly cold that the wagon train was able to cross safely on the ice. At Sugar Creek, nine miles into Iowa and almost in view of their former homes in Nauvoo, a temporary camp was set up. That night nine babies were born.”

The artist and his young Norwegian wife sailed to the United States in 1857. They made their way to the Mormon colony in Iowa City, where they bought a hickory handcart and set out to walk with a newly formed company to the valley of the Great Salt Lake. Thus the artist himself had experienced many of the situations which he represented. All of Christensen’s paintings which show the movements of large groups within a setting of nature have both a poetry and a veracity which make them particularly effective.

We turn now to the exodus of the last refugees. The description reads:

“The last of the Mormons driven from Nauvoo included many aged and ailing. At their first camp, near the Mississippi, they realized how poorly equipped they were for the westward trail. As they prepared their meager supper they heard overhead a wild whirl of wings. Thousands of quail descended among them. Soon they had caught enough to insure their having toothsome food for the first few days of their journey.”

And now, the arrival in the valley:

“On the last day of the long trek, President Young, weakened by mountain fever, mustered enough strength to ask Wilford Woodruff—in whose carriage he was riding—to turn the vehicle so that he might look out over the valley. From his seat, the weary leader could see across the long sea of grass over which a misshapen cedar tree lifted its crooked limbs. ‘This is the place,’ he said.”

With his imagination on fire and the compelling need to tell his story, the Mormon story, Christensen’s earnest awkwardness gives a kind of authenticity to the story. We value his veracity and find a charm in the poetic details and settings.

As a group, the paintings tell the story adequately and at times movingly. Some of the individual panels are sufficiently strong to be in and of themselves works of art—the Slaying of Joseph Smith, the panels of the Temple at Nauvoo, and The Burning of the Temple. Evaluated from the perspective of the history of American art, they are an interesting historical cycle done by a provincial artist of talent, that is, by an artist who has had some training and some exposure to the art of the past.

Though Christensen achieved naive effects, he is not what we call, for lack of a better word, a naive artist. A naive artist is one who is not only self-taught but is invincibly “ignorant,” or, we might say, blissfully ignorant, of the art of the past and of such studies as anatomy and perspective. His or her own way of seeing reality is paramount. However strange their visions may appear to us, most “naive” artists are convinced of the literal realism of their imagined worlds. In the little masterpiece of an anonymous artist called Meditation by the Seashore, we see a single figure looking out upon great waves, the ocean, and a distant ship. The proportions of his figure are odd, and the waves a decorative pattern. The shore and cliffs are from dreams, not reality. But this artist would be completely disinterested, and rightly so, in the study of anatomy and nature, which the professional artist must master. The naive artist paints as he sees, as he images, and he sees differently from most of us, and certainly differently from the professional artist.

A professional artist like Christensen’s contemporary, Thomas Eakins, not only spent years in the study of anatomy and dissection, but he taught anatomy to medical students at Jefferson Hospital in Philadelphia. Careful perspectival studies for his paintings of boating scenes or interior scenes exist. These studies lie behind the representation of persons, places, and things in his paintings, giving them an authentic and penetrating realism.

Of the three kinds of art and artists described, it is only the professional artist who is the maker of high art, who is technically equipped to communicate the inner being which animates the lineaments of the face and figure of a woman or man. Thomas Eakins, like Rembrandt, could depict a man or woman lost in thought, revealing the inner workings of their spirit.

Another kind of art flourished in the nineteenth century—the kind of popular prints which Currier and Ives published. Produced for mass distribution, these prints varied in quality from vigorous pictures of important events or picturesque places to sentimental and slick prints on subjects ranging from hearth and home to pious pictures for Protestant and Catholic devotions. The latter were not art, and one hopes the theologian would agree they were not religious. Their twentieth-century counterparts are the illustrations in the Bibles given to Catholic and Protestant children and in much of the church-school literature of those faiths. Also in this category of paintings for the masses are many of those to be seen in the Mormon visitors centers.

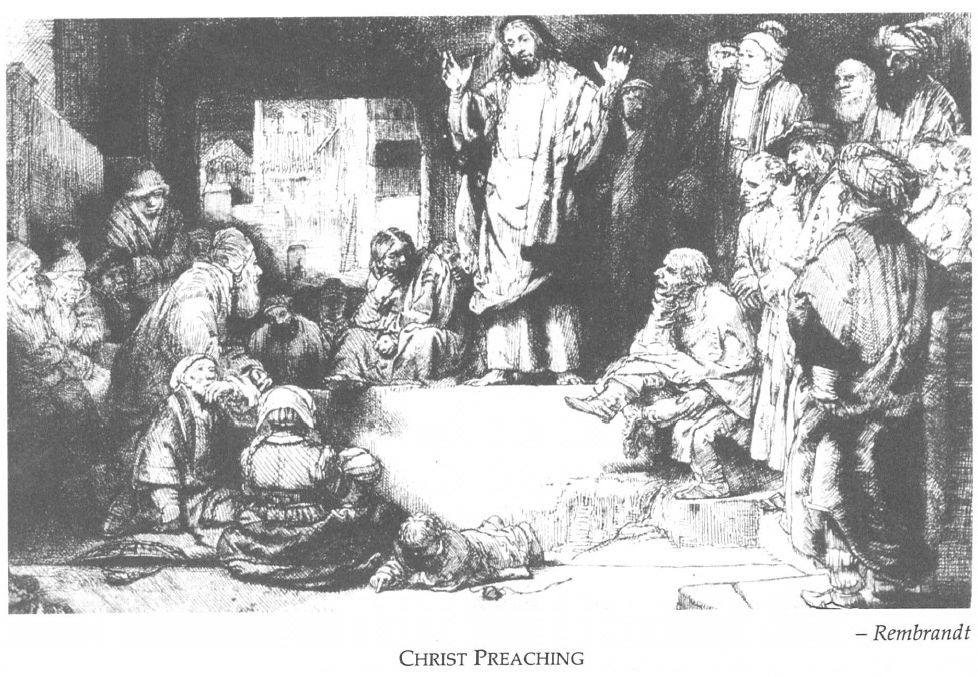

If we contrast Rembrandt’s etchings of biblical subjects with the illustrative art of the visitors centers, we are at once aware of the power and profundity of Rembrandt’s recreation of the Crucifixion event. The tragedy in human terms is eloquently depicted; the frail and vulnerable Christ upon the cross, the group below—individuals, yet each is caught within the dramatic surge of the tragedy which each contributes to or witnesses, by intent or by default. Nonetheless, the shower of light and the invincible posture of the frail Christ upon the high cross show the Christ to be indeed the Son of God and the event to be encompassed within the embrace of the Heavenly Father. By contrast typical visitors’ center paintings seem like stills from a movie, with extras dressed and posed and acting as directed. In style and content they are perilously close to the socialist realism of Russia and China, an art developed to communicate political doctrine but one which validates the political stance with religious allusion and iconography.

Christ Preaching is the subject of this etching by Rembrandt, but it is more commonly known as The Hundred Guilder Priest for the price paid for one of the first prints—a price considered very high in Rembrandt’s own day. It is the same subject essentially that I have seen in three different paintings in Salt Lake City. Yet those paintings are very near to colored photos enlarged to wall size. The intention of the artist in that case was to make the event seem illusionistically real. Great art is concerned with the appearance of reality only to transform it. Rembrandt suggests, evokes the divinity of Christ by his manipulation of the lights and darks about the Christ; his slightly off-center figure seems to radiate light, yet the deepest velvety blacks frame him. Deep shadows fall at the lower right, and light touches the arm and hand of a sick woman, a doughty old man listening, back to us at the left, a thoughtful brooding face in the crowd above. Much is suggested; nothing is delineated realistically. The biblical paintings for so-called educational purposes become within a generation dated and irrelevant, whereas art such as that of Rembrandt is timeless, and it rewards continuing and attentive viewing “time without end.”

Mormon Art, Christian Art, and Religious Art are all problematical terms. Any prefacing, limiting term before the word art creates problems. T. S. Eliot pointed out that to determine whether a poem or a painting is a work of art can only be done by the standards and disciplines of that particular branch of art. But to determine whether or not it is a religious poem or a religious painting, one must bring other standards to bear. Herein lies the problem.

Most art historians agree that there is good art and bad art, but not that there is Mormon Art, Women’s Art, Black Art, and so on. This conviction is not a matter of fine argument and distinctions, but conclusions drawn from the evidence. Michelangelo worked almost exclusively for the popes, yet his art could never be confined by the label “Roman Catholic Art.” Rembrandt’s biblical subjects, which come out of a Protestant culture, are as moving to Catholics as to Protestants. Christensen’s significant paintings are as expressive to me as they are to Mormons. Indeed, I believe that I, and historians of American art, value them more highly than do the Mormon people for whom they were made.

Protestant and Roman Catholic art used for educational purposes is no better than the Mormon art now in the visitors’ centers. But Protestants and Catholics alike have floundered in their educational efforts, whereas Mormonism has a highly developed and effective educational system which brings much emphasis on the visual image. With such a cohesive educational network encompassing family, church, and temple, the opportunity for educating the eye and the spirit through great art and for teaching the great truths through the great masters is limitless. Rembrandt and Michelangelo are as much a part of Mormon history as are Christensen’s paintings.

I would appeal to the Mormons to initiate a new “cleaning of the temple”—to remove the illustrative, shallow, socialist-realist-religious art, and await the coming of the artists who are equal to your epic history and your grand vision.