The Educational Legacy of Karl G. Maeser

A. LeGrand Richards

A. LeGrand Richards, "The Educational Legacy of Karl G. Maeser," Religious Educator 17, no. 1 (2016): 22–39.

A. LeGrand Richards (buddy_richards@byu.edu) was an associate professor of educational leadership and foundations at BYU when this article was published.

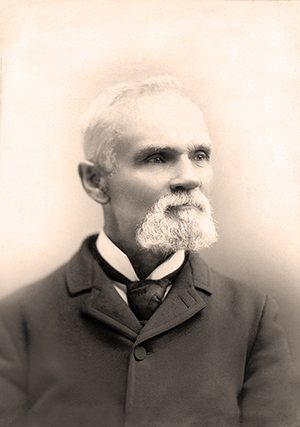

Karl G. Maeser

Karl G. Maeser

In 1855, German journalist Moritz Busch wrote a scathing book about Mormonism, scoffing at its naïveté and condemning its origin, while admiring the industrious accomplishments of its members. With remarkable accuracy he described the climate and geography of Utah, documented the history of the Church’s persecutions, and outlined the details of the plans for Salt Lake City. Busch wrote four chapters on Mormon doctrine and translated the Articles of Faith and several passages of the Doctrine and Covenants into German. But he couched his conclusions in the most derisive imagery, claiming that only in America could this “hollow nut” of fantasy and fraud grow into a gigantic tree whose “fruits are not entirely all rotten.”[1]

Of particular interest was Busch’s sarcastic review of Utah’s ambitions to establish a revolutionary university west of the Mississippi. He wrote that without an adequate knowledge of what a “real” university is, these “self-educated” Mormons, were planning a beautiful campus that would offer practical education in such ridiculous topics (as considered at the time) as engineering, farming, and mining. They promised they would “revolutionize the kingdom of the sciences,” overthrow the theories of Newton, and attract angelic regents from the university of heaven. Busch was convinced, however, that the Mormon emphasis on education would eventually backfire. He believed that if Mormons ever became truly educated, their entire house of cards would ultimately collapse.[2] It is more than a little ironic that perhaps the only person on the planet positively influenced by Busch’s caustic book was Karl G. Maeser, founder of Brigham Young University.

Reading this less-than-complimentary book on Mormonism ignited a flame in the young educator[3] that carried him across an ocean, gave him the courage to face remarkable obstacles, and inspired him to bring a unique educational perspective to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the western United States. Ultimately, Maeser became one of the most influential educators in the West. He trained thousands of teachers for both the Church academies and the district schools of Utah. He helped found over fifty schools, seven of which are now institutions of higher education (Brigham Young University Provo, Brigham Young University–Idaho, LDS Business College, Weber State University, Snow College, Dixie State University, and Eastern Arizona College). And yes, they even offer courses in electrical engineering, civil engineering, and agriculture. Decades after Maeser’s professional training, American educators would go to Germany to learn some of the ideas Karl was already applying. They called their movement “progressive education,” but when the movement went to Utah they were surprised that many of its practices were already there.[4]

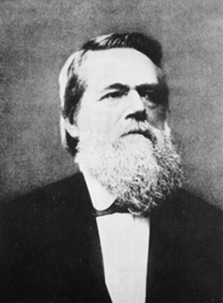

Moritz Bush (1821-99) was Maeser's most unusual "missionary."

Moritz Bush (1821-99) was Maeser's most unusual "missionary."

Early Career as a Teacher

At the time Karl read Busch’s book on Mormonism in 1855, he was an Oberlehrer at the Budich Institute (a private elementary school that also functioned as a teacher college to prepare young women to be teachers) in Dresden, Saxony. He had been trained at the Friedrichstadt Teacher College, where he developed an appreciation for the educational theories of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, who believed in the divine potential of every individual child, not merely of the children of the elite. The training Karl received in Dresden occurred in a brief window of time that was brutally closed just after Karl graduated in 1848, the year of revolutions in Europe. Rebellion had boiled over in many of the German provinces. Many people wanted a unified Germany with a common constitution that guaranteed the basic freedoms claimed in the United States. Karl had even supported a democratic movement before he accepted a three-year internship in Bohemia.[5] While he was away, revolution broke out in Dresden and the king of Saxony called upon Prussian troops to squelch it. The king of Prussia blamed the attempted revolutions of 1848 and 1849 on the teacher training programs and the educational theories that Karl had embraced. Most German states sided with Prussia in the reaction to education.

So Karl returned to Dresden, where he was offered a job (hundreds of teachers left Germany in the wake of the failed revolution) in the First District School, but he was forbidden from teaching the way he had been trained. He was forced to teach six hours of the prescribed religion per week, but he had lost faith in the state religion. He found Busch’s book while preparing to give a lecture at the Saxon Teachers Association and could not be content with a critical review of Mormonism. He had to investigate Mormonism for himself. His conversion story is one of the most interesting in Church history.[6]

Educational Philosophy in the American West

From such an unlikely beginning, Brother Maeser weathered remarkable hardships and sacrifice; he was forced to leave his homeland, deprived of financial security and respect, and exposed to the raw challenges of the desert frontier before Brigham Young invited him to organize a Church school in Provo, Utah. Brigham’s charge was a simple one: “Brother Maeser, you ought not to teach even the alphabet or the multiplication tables without the Spirit of God. That is all. God bless you, goodbye.”[7] Brother Maeser took this charge very seriously. After a few weeks, word came to Provo from Salt Lake City that Brother Brigham was coming in a few days to inspect the school and to hear the prospectus for the Academy’s program. This nearly sent Brother Maeser into a panic because it wasn’t ready. The school he had received had no plan, had hardly kept any records, and had buildings that were in poor repair. He wrote, “I worried Friday night, all day Saturday and Sunday and did not sleep Sunday night.” On Monday morning he played the organ for the choir and was still perplexed about Brigham’s visit. What was the plan he should show the President of the Church? “I leaned my head on my hand and asked the Lord to show me these things. I had it in a minute.” He spent the rest of the day putting the plan on paper, grateful that the Lord had answered his sincere prayer. He also added, “The spirit said to me, ‘Why did you not ask me Friday? I would have given it to you then.’” [8]

Outwardly the plan did not look very different from those of other academies across the nation. The topics of the courses sounded similar, and students were organized into the standard primary, intermediate, academic, and collegiate courses. But Maeser was convinced that the foundation of revelation set it apart from all other schools. He wrote, “We had the educational systems of the world to pattern after, but we beheld also their faults in the shape of infidelity, of disregard of parental authority and old age, of corruption, of discontent, and of apprehension of unknown evils yet to come.”[9] He noted that in the same way an oak sapling does not look very different from a fully grown corn stalk, the BYA may have looked similar to other institutions but was built of much stronger spiritual fiber. [10] A secular curriculum with a built-in seminary was not sufficient for this school. “The Spirit of God” was to permeate “all the work done; whether it were class work or disciplinary labor.” [11]

Most of the educational approaches of the day were built on fear and competition. Corporal punishment dominated, even in Utah schools. Maeser welded the ideas of Pestalozzi and Froebel to his understanding of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. This position held that love, confidence, and personal responsibility could become the basis of a much more powerful learning experience. For Maeser, the most powerful incentive for learning was spiritual. He saw education as the process of becoming aware of one’s divine mission and choosing to develop the capacity to fulfill it. He did not believe that this mission could be known without personal revelation; hence his statement, “Nor can methods of squeezing immortal souls into a common mould be called education.”[12] Rather, true education recognizes “the necessity for self-activity, self-investigation, and self-research, and cultivate[s] the spirit of inquiry within them.”[13]

At the conclusion of his tenure as principal in 1892, Maeser claimed that there were two founding principles of the Academy and that it would be disastrous to the institution if it ever deviated from them.[14] The first was the injunction from Brother Brigham to teach all subjects with the Spirit of God and the second was the directive from the Prophet Joseph to teach them correct principles and let them govern themselves. With Pestalozzi, Maeser believed that every aspect of learning that could be handed over to the students themselves should be given to them. Students took over course mechanics, monitored each other’s progress, and learned leadership skills by sharing responsibilities and mentoring each other.[15] They were encouraged to ask and answer their own questions.

Widespread Influence on Teaching in the West

As the reputation of the Brigham Young Academy spread, other areas expressed the desire to pursue Maeser’s vision of an ideal education, one that fully integrated the gospel into every subject. He drafted a plan to the First Presidency to establish academies in every stake of the Church, patterned after BYA.[16] This was approved, and in 1888 the Church Educational System was established with Maeser as its first superintendent. While still serving as the principal of the Brigham Young Academy, which became the Church’s teacher college, Brother Maeser helped establish academies and seminaries from Canada to Mexico.[17] Travel to these academies was arduous and time consuming. Supplying a sufficient number of prepared teachers and sufficient resources to sustain these academies was almost overwhelming. Even so, as mentioned earlier, seven of these academies are now institutions of higher education.

Lesser-known of the Maeser legacy was his influence on the public schools of the Utah Territory. When he arrived in Utah in 1860 he was appointed as a regent of the University of Deseret (now the University of Utah),[18] which served as a type of board of education for the district schools. He helped found the first Territorial Teachers Association in Utah and was an active participant in the Association throughout his career. From his earliest years in Germany, Maeser was actively engaged in preparing teachers, and he carried his experience and passion to Utah. He helped establish the first teacher preparation courses at the University of Deseret and served as the president of the Salt Lake Teachers Association.[19] He knew that his ideal of an education that fully integrated the gospel into all subjects was not possible for all students, so he also supported district schools by preparing as many faithful Latter-day Saint teachers as practicable. Maeser knew that these teachers were under strict edict to refrain from sectarian instruction, but he also knew that faithful Latter-day Saint teachers would not seek to undercut the faith of their students. From 1876 on, at least half of the teacher candidates in his teacher preparation classes were preparing to teach in the district schools. He held in-service courses for district teachers on weekends starting in the fall of 1876. [20] Maeser was elected to the Utah Constitutional Convention and had an important influence on the education committee. He helped decide the location of the southern branch of the state normal school (now Southern Utah University) and personally trained most of its original faculty.[21] It was most appropriate, therefore, that a public school in Provo was named after him in 1898.[22] Maeser’s contribution to public education was substantial.

Maeser also recognized that public schools, as nonsectarian, would be prohibited from building on the same spiritual foundation as the Academies. As superintendent of Church schools he was commissioned to draft the first curriculum for religion classes that were to be held in the wards during the week to supplement the secular education provided in the district schools.[23] When President Lund gave him the assignment, Maeser replied, “I have the plan already.” He felt inspired to draft the plan a year previous but did not feel it his place to suggest it before receiving the assignment.[24] This plan has evolved into the seminary and institute programs of the Church.

Writings and Sayings

Maeser wrote only one book (School and Fireside) but delivered thousands of addresses and wrote dozens of articles. His tireless efforts culminated in numerous lasting contributions to the Church. For example, upon his arrival in Salt Lake City, he helped organize the German home mission. The German saints would gather one evening in the week to hear a German translation of the sermons offered in the bowery on Sundays.[25] Later this evolved into German meetings held in Salt Lake and other cities. As Swiss Mission president in 1869, Maeser began publishing Der Stern, a Church magazine that has continued (now as the Liahona). He translated twenty-nine of the best-known English hymns into German (including such favorites as, “The Spirit of God,” “How Firm a Foundation,” “We Thank Thee, O God, for a Prophet,” “Do What Is Right,” “Ye Elders of Israel,” “Praise to the Man,” “O My Father,” “The Time Is Far Spent,” “Now Let Us Rejoice,” “Come, Come Ye Saints,” and many more. Most of his translations of these hymns are still used in the German Gesangbuch. He translated about a third of the Doctrine and Covenants into German[26] and put the German translation of the Book of Mormon into chapter and verse,[27] consistent with the English translation. He served four full-time missions for the Church; it would be difficult to identify any year following his conversion that he was not also serving a mission.

Known for his sentence sermons, Brother Maeser wrote hundreds of sayings that have been repeated in numerous settings. The most famous of these is not found in his writings, but as far as I can tell was first quoted by Richard Lyman, one of his students:

My young friends, I have been asked what I mean by word of honor. I will tell you. Place me behind prison walls—walls of stone ever so high, ever so thick, reaching ever so far into the ground—there is a possibility that in some way or another I may be able to escape, but stand me on that floor and draw a chalk line around me and have me give my word of honor never to cross it. Can I get out of that circle? No, never! I’d die first.[28]

Other sayings can be found directly in his own writings, including:

“Be yourself, but always your better self.”[29]

“Make the man within you your living ideal.”[30]

“Man grows with his higher aims.”[31]

“Nature is the best educator.”[32]

“School is a drill for the battle of life; if you fail in the drill you will fail in the battle.”[33]

“Every one of you, sooner or later, must stand at the fork of the road, and choose between personal interests and some principle of right.”[34]

“The exercise of authority without intelligent justice and kind consideration is tyranny, and obedience without consent of heart or brain is slavery.”[35]

“We can never give what we ourselves do not possess.”[36]

“Strive to be yourself that which you desire your children or pupils to be.”[37]

“The law is not made for true men and women but for criminals.”[38]

“Because a man does not steal while in prison does not make him honest.”[39]

“A slave does a thing because he must, a free man because he wills to do it.”[40]

“The strongest incentives to discipline are love and confidence.”[41]

“No teacher should teach by precept who cannot teach by example.”[42]

“Navigators do not take their reckoning from the flaming comet, but from the fixed stars.”[43]

“Knowledge is not power unless it is sustained by a character.”[44]

“Mar a sapling and the full-grown tree will show the scar.”[45]

“A quiet school may be a failure. Graveyards too are quiet.”[46]

“An overburdened animal [or student] refuses to rise.”[47]

“Providing good school buildings without paying the teachers adequately is like stealing the oats from the horses to pay for the grand stable and carriages.”[48]

“The home is the sanctuary of the human race, where each generation is consecrated for its life’s mission.”[49]

“With the removal of religion as the fundamental principle of education, our public school system has been deprived of the most effective motive power.”[50]

“The promise of the beautiful rainbow is visible only to those who face the storm with the sun at their backs."[51]

He wrote my favorite of his sayings on the chalkboard of the Maeser School November 9, 1900 (three months before he died): “This life is one great object lesson to practice on the principles of immortality and eternal life.” This saying welds Maeser’s professional training as a Pestalozzian teacher with his faith in the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. Object lessons for a Pestalozzian educator meant far more than a clever way to introduce a pre-planned lecture. They represented an invitation to study some natural object carefully to discover what it might teach us. The great teacher will observe objects with the students, ask provocative questions, and listen to the observations and insights of the students.[52] To study life in its eternal context and to learn from it the principles of eternity links man with God’s work and glory. Every teacher, then—not only those assigned to teach doctrine— enters sacred ground and has “the mission of an angel to perform.”[53] What higher aspiration might we seek?

Legacy of Faith and Vision

Brother Maeser grounded his educational philosophy in his view of the restored gospel. He believed that the greatest incentive to learning is fundamentally spiritual because each person has a divine mission to discover and fulfill. The task of the educator is to help awaken this sense of mission and to inspire the learner to make the necessary choices. Maeser opposed the coercive educational methods of his day that were based on the lower Mosaic law of “thou shalt and thou shalt not.” This approach tends to elicit the response, “Okay, if I have to.” Maeser taught that Christ invited us to the higher law: “Come, follow me.” This encouraged the “I will” of moral agency.[54] Not only did he oppose corporal punishment in schools, Maeser taught that other coercive educational approaches that feed on competition, comparison with others, and external rewards by mortal assessments ignored the motives that could drive the educational experience much further.

Maeser believed that faith and confidence in the students can help unleash the most powerful incentives, which are religious. He told his students that he would trust them until they demonstrated that they were not trustworthy.[55] He invented tasks for students to do so they would learn to do things on their own and develop a sense of public spirit by serving each other.[56] He believed teachers should not do for students what they could do for themselves, and he encouraged both teachers and students to realize that all true education is “self-education.” This was especially true when the students sought to become what God would have them be.

For Maeser then, the role of teacher was a sacred one. He believed that teachers were not to see themselves as the primary source of knowledge for their students; rather he took seriously that God is the source of truth and that students should be directed to Him for truth and that the process itself would edify. He taught that in Moses’ day a fence was placed at the base of Mount Sinai, prohibiting all but Moses from climbing to the presence of God. Maeser believed, however, that the fence has now been removed and that the ascent is now open to all who are spiritually willing to make the climb.[57] Teachers can encourage the climb, but should avoid substituting for Him to whom we must all someday account.

Maeser held very high expectations for his students, but he rarely prescribed them in specific detail. He had a remarkable capacity to imagine their potential. He also realized, however, that such potential would be developed only by the diligent efforts of each moral agent. At the same time, Maeser developed a keen sense of humor that was deeply endearing. One day Dr. Maeser was late for class. This was a rare experience, but in his absence a few of the young men had an idea for a prank. They had noticed a donkey outside of the school and brought it into the classroom, tying it to the teacher’s lectern. Then they waited for Dr. Maeser’s response. Not about to overreact, the seasoned teacher sized up the situation quickly and quipped, “Dat is right, dat is right, when I am not available, you should appoint the smartest one among you to take my place.”[58] He had the capacity to enjoy the humor of a moment without losing a focus on eternity.

Brother Maeser knew that teachers face two different kinds of students. One comes to school, easy to love. They usually come from homes that support them, are grateful to be there, and are ready to learn. He noted that they may be successful regardless of our help. But there are also students who may not be easy to love at all. In fact, they may resent coming to school, greet you with disdain, and curse at you when they arrive. They may not wear the best clothes or have very positive experiences in their own homes. These were the ones that, like flowers growing in a cellar, require special attention. These were the ones that teachers could launch into a new trajectory and have the greatest impact on. He believed that if the teachers would ask in prayer, the Lord would help them know the best approach for every type of student, especially those that needed special attention.[59]

Maeser left us a legacy of faith, service, and vision. He battled with his own weaknesses and had to face remarkable challenges. He taught that the truths he knew were “not learned from books alone. They are gained from life's bitter school and in the darkest hours.”[60] His ideas were refined in the furnace of affliction and consecrated through his sacrifices. Financially, he struggled all his days after joining the Church. It must have been humiliating for a refined former German professor to push a wheelbarrow from door to door to collect tuition in turnips, squash, and cabbages and to beg for any extra morsels his students’ families might be able to spare. His appointment as principal of the Brigham Young Academy never meant financial security; in fact, the Academy faced financial collapse at numerous points during and after Maeser’s tenure as principal. In January of 1884, for example, the uninsured Academy building was destroyed by a devastating fire, but Maeser doggedly insisted it was only the building that was demolished. “The Academy lives on.”[61]

Maeser developed a vision of what the Academy would someday become, but sometimes he had to hold that vision almost by himself. At one point he became sorely discouraged; he had been overworked and hadn’t been paid for over six months (again). A foundation for the new academy building had been laid, but they had lacked the funds to build on it for eight long years. His closest friends accused him of spending so much time attempting to help establish another academy in Salt Lake City that he was neglecting BYA. He felt that his own board was indifferent to whether he stayed or left the Brigham Young Academy, so he told his family that it was unfair to them to have to sacrifice so much. The Maeser family packed their bags so that they could move to Salt Lake where Brother Maeser could obtain a more secure position. Days passed and they didn’t move. When Maeser’s daughter finally confronted her father about when they would be moving, he told her that he had changed his mind: “I have seen Temple Hill filled with buildings—great temples of learning, and I have decided to remain and do my part.”[62] It would not have been easy to imagine the more than three hundred buildings that now fill what was then a sagebrush-covered east bench nor would it have been easy to conceive of the type of financial support available to the Brigham Young University today.

In January 1892, Maeser led a procession of students up Academy Avenue to the new education building (now the Provo City Public Library), gave his final address as principal of BYA, and turned the reins over to Benjamin Cluff. But Maeser’s “retirement” from BYA was hardly a retirement in any sense of the word; he transferred his full-time effort to his assignment as superintendent of Church schools by teaching, training, encouraging the work, and visiting each school from Canada to Mexico at least annually. With the conveniences of modern travel, few of us can appreciate how difficult such travel was at that time by rail and buggy. In 1894, Maeser was called to serve as the mission president in California for seven months while he represented the Church Educational System at the San Francisco World’s Fair. Maeser’s remarkable diligence has left an indelible imprint on the progression of the Church’s educational system.

I think Brother Maeser would consider his most important legacy, however, to be the personal impact he had on his students and family. His own life stands as a powerful object lesson to all those willing to study the details. George Sutherland, for example, was a student of Maeser and became a senior justice of the US Supreme Court. He knew a number of great intellects and never joined the LDS Church but declared of Brother Maeser, “I have never known a man whose learning covered so wide a range of subjects, and was at the same time so thorough in all. His ability to teach ran from the Kindergarten to the highest branches of pedagogy. In all my acquaintance with him I never knew a question to be submitted upon any topic that he did not readily and fully answer.” Sutherland attributed his own love of the US Constitution to this powerful teacher.[63]

George Albert Smith, eighth President of the Church, spent a fairly short amount of time as a student of Brother Maeser but declared, “The influence of that good man on my life was so great that I am sure it will endure for eternity.”[64] Others, such as James E. Talmage and Reed Smoot, spent years under Maeser’s tutelage and regularly sought out his counsel before making major decisions in their lives. At the age of eighty-seven, Amy Brown Lyman, who served as the eighth general president of the Relief Society, described Brother Maeser’s profound influence on her: “Next to my own parents he has influenced my life most.”[65] Some of his students thought the power of his personality could never be accurately described. “He had a magnetic power of inspiration.”[66]

As a twenty-eight-year-old mule skinner in northern Utah, J. Golden Kimball heard Brother Maeser speak to a small group about education and was so impressed by it that he determined to move to Provo in the dead of winter (by wagon and team) in order to study with him. Similarly, Benjamin Cluff walked to Provo from Heber City (about forty miles) in order to study with Maeser. Later, Cluff had the privilege of studying with some of the most renowned educators in the country, including Francis Parker, John Dewey, G. Stanley Hall, George Herbert Mead, and Charles W. Eliot. About Brother Maeser, Cluff wrote, “Of all the teachers whom I can now recall, none is more prominent and none is recalled with more respect and affection than is Dr. Karl G. Maeser.[67]

Maeser often expressed the desire to die in the harness, serving the Lord and his children. After inspecting the Weber Stake Academy, where young David O. McKay was teaching, Maeser spent February 14, 1901, in his Salt Lake City office writing letters. In the afternoon he presided over the General Board meeting of the Church Sunday School. That evening he entertained his family before retiring for the night. Peacefully and quietly his spirit left his body in the early hours of the next morning.[68]

Word quickly spread that the beloved teacher had died. Immediately plans were made to mourn his loss and celebrate his final graduation. The funeral held in the Salt Lake Tabernacle was the kind reserved only for the most notable Church authorities. The major schools in Utah were closed, the Utah State Congress adjourned, and letters of tribute flowed in from all parts of the Church. Members of the First Presidency spoke and members of the Quorum of the Twelve served as pallbearers. A special train was scheduled to bring attendees from Utah Valley.[69] Separate memorial services were held in Provo; Beaver; Castle Dale; Ephraim; Vernal; Thatcher, Arizona; Juarez, Mexico; and other places throughout the West. The outpouring of love for Maeser at his passing stood as a testimony to the personal impact he had on concourses of people.

At Maeser’s funeral, Elder Heber J. Grant, future President of the Church, declared that if all the effort, sacrifice, and expense required to open the German mission had done nothing more than lead to the conversion of Karl G. Maeser, “all the time and the money would have been well spent.”[70] President George Q. Cannon, representing the First Presidency, continued by expressing how “profoundly learned” Brother Maeser was, “yet so humble” that it seemed almost impossible to find a replacement for him. “He had an overwhelming love for children.”[71] Cannon hoped that the people of Zion would emulate Maeser’s life. Those of us who are the benefactors of this great man should appreciate the lessons that we too can learn from his life.

The Maeser legacy stands as a remarkable heritage and challenge. He took seriously the prophecy of President John Taylor that the day would come that “Zion will be as far ahead of the outside world in everything pertaining to learning of every kind” as it was regarding religious matters.[72] He recognized that this prophecy would not be fulfilled by copying what other institutions were doing any more than superiority in religious matters would come by copying the organization or doctrine of other churches. His model of education operated on the principle that God is the author of all truth and will reveal it according to the faith and diligence of His children in asking, seeking, and listening to His divine promptings. Of course such seeking will require sincere study, diligent effort, and profound research, but it will be undergirded with a learning by faith that will purify the seeker as well as bless mankind. When combined with the basic covenants and ordinances, seeking knowledge from God will bring promised answers and personal exaltation.

Maeser warned that the “prevailing system of competition” in schools engenders a spirit of selfish ambition.[73] Zion cannot be built up by anything that feeds such pride. An education to build Zion, then, must be built upon the principles of the celestial kingdom (see D&C 105:5), so all other approaches will eventually be found wanting. He might encourage us today to live up to the principles of education that have already been revealed and to seek truth from the author of truth and let our good works shine that others may see them and glorify our Father in Heaven, not us. Maeser would encourage us to hold true to the promises made by prophets, seers, and revelators regarding the potential to seek learning also by faith in all subjects, temporal as well as spiritual. By doing this we will be building on the sure foundation Maeser helped lay. To this end, his words echo through the decades: “Claiming the privilege of a veteran in the cause, I feel to exhort all parents and teachers of this younger generation to accept the work of latter-day education as a sacred heritage and to carry it to its final consummation, . . . thanking my Heavenly Father . . . for the privilege of beholding among our people the opening of an educational era in which our youth shall be prepared for their glorious destiny”.[74]

President Kevin J Worthen has invited us to stretch ourselves spiritually and intellectually to new heights by going “to the mountains.”[75] Brother Maeser encouraged teachers to do the same: “I may not live to see the day when teachers will be on the top of the mountains, but you ought to get there. . . . What a glorious hope lies before you.”[76]

Notes

The ideas of this article are developed more fully in A. LeGrand Richards, Called to Teach: The Story of Karl G. Maeser (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center and Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2014).

[1] Moritz Busch, Die Mormonen: Ihr Prophet, ihr Staat und ihr Glaube [The Mormons: Their Prophet, Their State and Their Faith] (Leipzig: Carl B. Lorck Verlag, 1855), 2; translation by A. LeGrand Richards.

[2] Busch, Die Mormonen, 69.

[3] See A. LeGrand Richards, “Moritz Busch’s Die Mormonen and the Conversion of Karl G. Maeser,” BYU Studies 45, no. 4 (2006): 47–67.

[4] For example, when John Dewey taught the BYU Summer Seminar in 1905, he told them, “I judge from what little I have seen in this state that you are already far advanced in that direction.” John Dewey, “Dr. Dewey’s Lectures,” UA SC 21, box 2, folder 1, 186, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University. Francis Parker, often called the father of progressive education, had a similar reaction in 1892 when he lectured at the BYA Summer Seminar. See Francis W. Parker to Karl G. Maeser, November 5, 1892, Church History Library (hereafter CHL)).

[5] See “Dr. Maeser’s Jubilee,” an appendix reporting a celebration for Dr. Maeser on his fiftieth anniversary as a teacher added to the 1898 edition of Karl G. Maeser, School and Fireside (Provo, UT: Skelton, 1898), 352.

[6] Chapters 3 and 4 of Called to Teach describe his conversion in great detail.

[7] Reinhard Maeser, Karl G. Maeser: A Biography (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1928), 79.

[8] “Founders Day Exercises,” The White & Blue, October 15, 1900, 12. Alma P. Burton refers to a story told by Ida Stewart Peay probably about this same experience. Alma P. Burton, “Karl G. Maeser, Mormon Educator” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1950), 62; see also Ida Stewart Peay, “The Story Dr. Maeser Told,” Improvement Era, January 1914, 194.

[9] Karl G. Maeser, “The Brigham Young Academy,” Normal, November 13, 1891, no. 6, 43.

[10] Maeser, School & Fireside, 161.

[11] “Salt Lake Stake Conference,” Deseret Weekly News, September 17, 1898, 441.

[12] Maeser, School and Fireside, 264.

[13] Maeser, School and Fireside, 291.

[14] Karl G. Maeser, “Final Address,” Normal, January 15, 1892, 82, LH 1.B73 B5, LTPSC.

[15] See, for example, Maeser, School and Fireside, 250.

[16] Franklin D. Richards, journal, July 29, 1887, Richards family collection, MS 1215 4 36 222, box 4, reel 4, CHL.

[17] In Maeser’s day, a seminary was a feeder school to an Academy. It generally offered only the primary and intermediate courses. Only one Academy per stake was authorized.

[18] “Election of the Territorial and Other Officers by the Legislative Assembly,” Journal History of the Church, December 24, 1860, vol. 53, reel 18, CHL.

[19] Robert Campbell, “Correspondence,” Deseret News, November 29, 1871.

[20] See “Register of Studies,” October 27, 1876, UA 229, L. Tom Perry Special Collections; see also “Our Country Contemporaries,” Deseret Weekly News, December 27, 1876, 4.

[21] “State Normal School,” Salt Lake Herald, April 9, 1897, 7. Three of the first four faculty were graduates of BYA. See Anne Okerlund Leavitt, Southern Utah University: The First Hundred Years, A Heritage History (Cedar City, UT: Southern Utah University, 1997).

[22] Maeser School in southeast Provo was dedicated in 1898.

[23] General Board of Education meeting minutes, October 8, 1890. UA 1376, box 1, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[24] Statement by Eva Maeser Crandall, March 25, 1950, in Burton, “Karl G. Maeser,” 106.

[25] Karl G. Maeser, “Constitution of the German Intelligence Office,” in Correspondence, UA 1094, folder 1, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. This is not dated, but it was likely in October 1860.

[26] In each of the early issues of Der Stern, Maeser included a German translation of a section of the Doctrine and Covenants.

[27] Karl G. Maeser to Wilford Woodruff, July 16, 1888, Karl G. Maeser correspondence, UA 1094, box 1, folder 4, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, 44.

[28] Richard R. Lyman, interview by Alma P. Burton, February 1950, in Burton, “Karl G. Maeser,” 50. I have not found this quotation in any of Maeser’s actual writings or as recorded by any contemporary secretary. Lyman had been a secretary and kept the minutes of the domestic department in 1888–89 but did not record it in the extant notes. It is not out of character, however, and similar statements are found in the minutes and in School and Fireside: “A young man once asked me, what the Word of Honor meant. I answered him: ‘If I should give you my Word of Honor about anything, I would die before I would break it’” (291). On September 27, 1888, Richard R. Lyman recorded that Maeser gave some “incidental” instruction: “Wished he could let us know how he felt when he lost confidence in a student, that he would rather lose his life than his honor. Honor is easily broken but very hard to restore, and we should undergo any inconvenience rather than break ours.” “Records 1879–1900,” Richard R. Lyman, recorder, UA 195, folder 2, 45, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[29] The earliest recorded version of Maeser’s aphorism that I could find was cited in N. L. Nelson, “Dr. Maeser’s Legacy to the Church Schools,” Brigham Young University Quarterly 1, no. 4 (February 1, 1906), 14. See also “Dr. Karl G. Maeser—Some of His Sentence Sermons,” Millennial Star, July 16, 1908, 452, and “Sentence Sermons by the Late Dr. Karl G. Maeser,” Improvement Era, September 1939, 513. Perhaps this version was paraphrased from “Let every teacher try to be genuine, himself, his better self, striving to approach nearer and nearer to his ideal.” Maeser, School and Fireside, 279.

[30] Reed Smoot, in Conference Report, October 1937, 328.

[31] Maeser wrote this saying on one of chalkboards at the Maeser School on November 9, 1900. I was in charge of preserving three of the four chalkboards. They are now in the BYU Archives. For more information on Maeser’s sayings, see “Provo: Sentiments of Dr. Maeser,” Deseret News, February 23, 1901.

[32] Maeser, School and Fireside, 64.

[33] Cited “Dr. Karl G. Maeser—Some of His Sentence Sermons,” 452.

[34] “Sentence Sermons,” 513, 549.

[35] Maeser, School and Fireside, 245.

[36] Karl G. Maeser, “Sunday School Lectures,” Deseret News, June 25, 1892.

[37] Maeser, School and Fireside, 266.

[38] Domestic Department Minutes, February 19, 1880, recorded by J. L. Robinson, UA 195, folder 4, 103, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[39] Domestic Department Minutes, April 11, 1889, recorded by Richard R. Lyman, UA 195, folder 2, 77, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[40] Domestic Department Minutes, February 27, 1890, recorded by Robert Anderson, UA 195 folder 2, 96–97, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[41] Maeser, School and Fireside, 205.

[42] “Emery Stake Sunday School Conference,” Deseret Weekly News, November 23, 1895, 718.

[43] George Brimhall, “Continuity in Character,” Improvement Era, October 1899, 929.

[44] Domestic Department Minutes, February 14, 1889, recorded by Richard R. Lyman, UA 195, folder 2, 74, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[45] “Dr. Maeser’s Lectures,” Deseret Weekly News, June 18, 1892, 846

[46] Karl G. Maeser, cited in “The Teachers’ Association,” Daily Enquirer, October 8, 1886, 3.

[47] Compare Maeser, School and Fireside, 278.

[48] Compare Maeser, School and Fireside, 93.

[49] Maeser, School and Fireside, 59.

[50] Maeser, School and Fireside, 56.

[51] Compare Karl G. Maeser, “Voices from Nature: The Rainbow,” Juvenile Instructor, March 1, 1867, 34.

[52] This approach is introduced in Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, How Gertrude Teaches Her Children, trans. Lucy E. Holland and Francis C. Turner (London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1907).

[53] “Dr. Maeser’s Lecture,” Deseret Weekly News, June 25, 1892, 21.

[54] “Maeser, School and Fireside, 116.

[55] J. L. Robinson, “Domestic Notes,” March 11, 1880, 106, UA 195, folder 4, L. Tom Perry Special Collections. ns.g: Guiding Readers to Christns.g: Guiding Readers to Christns.g: Guiding Readers to ChristKarl G. Maeser,

[56] Richard R. Lyman, recorder, “Theological Minutes,” March 7, 1879, UA 228, 45, 75, L. Tom Perry Special Collectio

[57] Maeser, School and Fireside,

[58] Other versions phrase it differently: “When I am detained always choose the brightest one among you,” in Mabel Maeser Tanner, “My Grandfather Karl G. Maeser.” “Dat is right, dat is right, when I cannot be present at our meetings, appoint one of your own number to preside,” in Eva Maeser Crandall interview, March 25, 1950, interviewed by Burton, “Karl G. Maeser,”

[59] “Dr. Maeser’s Lecture,” Deseret Weekly News, June 25, 1892,

[60] Allie Canfield, recorder, “Theological Minutes,” March 9, 1884, 21

[61] Ernest L. Wilkinson and W. Cleon Skousen, eds., Brigham Young University: A School of Destiny (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1976), 74–

[62] Wilkinson and Skousen, Brigham Young University: A School of Destiny,

[63] George Sutherland, A Message to the 1941 Graduating Class of Brigham Young University from Mr. Justice George Sutherland (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 194

[64] George Albert Smith, in Conference Report, April 1949, 83. Later he wrote that he was especially impressed by Brother Maeser’s comment, “Not only will you be held accountable for what you do and say, but for what you think.” “Dr. Karl G. Maeser Memorial: Tributes from His Students, a Pictorial History of the Brigham Young University, Including the Maeser Memorial Building” (Lehi, UT: Lehi Banner, 1907),

[65] Amy Brown Lyman, “Notes for the Dedication of the Karl G. Maeser Monument,” Amy Brown Lyman Collection, MS1070, C

[66] Edward Schoenfeld, “A Character Sketch of Dr. Karl G. Maeser,” Juvenile Instructor, March 15, 1901, 1

[67] Wilkinson and Skousen, Brigham Young University: A School of Destiny, 1

[68] “Editorial Thoughts: Assistant Superintendent Karl G. Maeser,” Juvenile Instructor, March 1, 1901, 1

[69] “Dr. Maeser Is Laid to Rest,” Deseret News, February 19, 1901,

[70] “Dr. Maeser’s Funeral,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 20, 1901,

[71] “Dr. Maeser Is Laid to Rest,”

[72] John Taylor, address in Ephraim, Utah, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 21:1

[73] Maeser, School and Fireside,

[74] This Maeser quote was written on the blackboard at the Karl G. Maeser memorial service held at the academy at Juárez, Mexico. See “Memorial Services in Honor of Dr. Karl G. Maeser,” Deseret News, March 1, 1901,

[75] Kevin J Worthen, “Enlightened, Uplifted, and Changed” (inaugural address, Brigham Young University), September 9, 2014,

[76] From an address given at the summer institute, August 16, 1893, Provo, UT, in “The Teachers Institute,” Deseret Weekly News, August 26, 1893