Excavating a Christian Cemetery Near Selia, in the Fayum Region of Egypt

C. Wilfred Griggs

C. Wilfred Griggs, “Excavating a Christian Cemetery Near Selia, in the Fayum Region of Egypt,” in Excavations at Seila, Egypt, ed. C. Wilfred Griggs, (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1988), 74–84.

C. Wilfred Griggs was a professor of ancient scripture and director of ancient studies in the Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University when this was published.

May I begin this report with an expression of gratitude to Dr. Ahmed Kadry, Dr. Ali Kholy, Mr. Mutawe Balboush, and other officers and members of the Egyptian Antiquities Organization, for generous interest and support for Brigham Young University in its excavation work at the site of Seila. The excavation staff members express heartfelt gratitude to the Mormon Archaeology and Research Foundation and its director, Mr. Wallace O. Tanner, and to Brigham Young University and its administrators for temporal and financial support for the Seila excavation project.

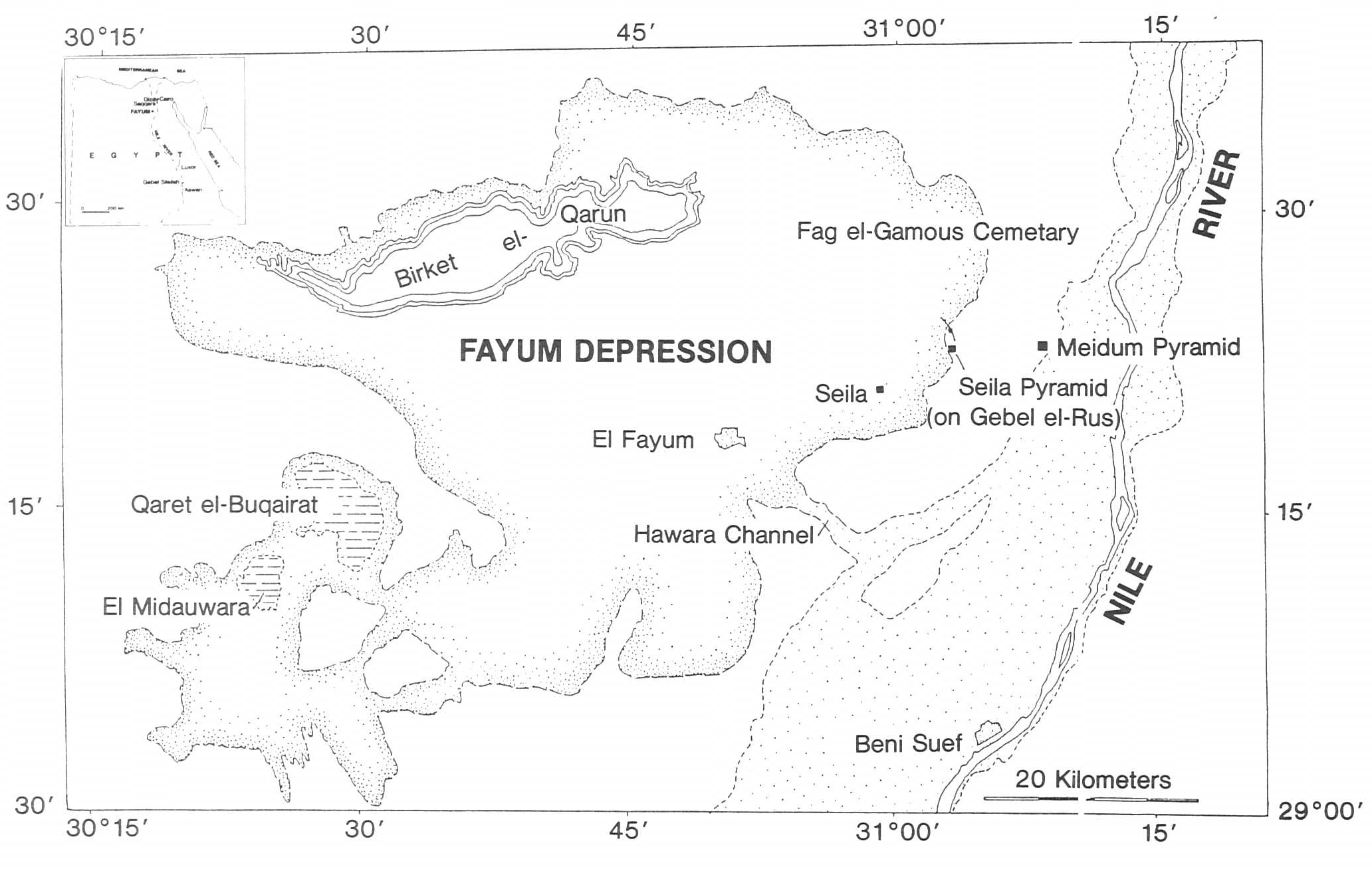

The archaeological site of Seila, taking its name from a nearby Egyptian village close to the eastern edge of the Fayum depression (see fig. 1, a map showing the site in relationship to the Fayum depression), is comprised of numerous components representing the entire scope of Egyptian history. Brigham Young University began work at the site in 1980, working jointly with the University of California at Berkeley that year, and having sole responsibility for the excavation since 1981.

The oldest monument in the concession is the four-step pyramid of Seila constructed in the early Third Dynasty atop the Gebel el-Rus and situated on a line directly east of the 4th Dynasty Meidum pyramid. What relationship may exist between the later Meidum pyramid, the southernmost of the pyramids along the so-called Pyramid Row of the western edge of the Nile valley, and the earlier Seila pyramid, built on a ridge at the eastern edge of the Fayum depression and visible from both the Fayum and the Nile valley, is yet to be determined. During the 1981 season the BYU-Berkeley team removed the sandy debris from about one half of the exposed portion of the pyramid. Beneath the dust and sand accumulated over five millennia was a weathered and eroded surface, but some lower portions of the walls were protected from weathering by the aeolian sands, and there the limestone blocks are in quite good condition, measuring, on the average, 1 X 1/

Approximately 2 km northwest of the pyramid and adjacent to the Abdallah Wahbi canal, which borders the cultivated land on the east of the Fayum, is an ancient cemetery which now bears the name Fag el-Gamous (Way of the Cow). A large limestone stele was erected on the western edge of the cemetery, not far from the canal (probably adjacent to the road leading south from Philadelphia, about 5 km north of the cemetery), and perhaps was intended to be an identification marker or dedicatory monument relating to the entire area. The stele is so badly weathered, however, that no markings remain on it which would assist in determining its function. The cemetery itself, covering approximately 300 acres (125 hectares), is almost entirely unplundered, though repeated digging for interment of bodies and later subsidence of the burial shafts have left the entire area in a very disturbed condition. A few very deep shafts, ranging from 15 to 23 m in depth, have horizontal shafts and burial chambers leading from the base of the vertical shafts, and these date probably from the Middle Kingdom. One unfinished burial chamber, beginning with a large room (c. 3x3 m) hewn from a limestone ridge running east-west in the cemetery continues north in a shaft for approximately 4–5 m before turning east in an unfinished burial chamber. Other rectangular shafts approximately one meter square and hewn into the small hills and mounds of the cemetery area angle downward and appear to turn horizontally left or right to burial chambers, but these have not yet been excavated, and firm dates cannot be assigned to them.

The BYU team has concentrated in an area of the cemetery which dates from the first century before the common era through the eighth century BCE, based on artifact analysis, including pottery, coins, textiles, and jewelry.

Within the portion of the cemetery excavated to the present time, two patterns of interment can be distinguished. The first consists of shafts hewn through the limestone bedrock to varying depths for burial. The most shallow are approximately one meter deep, into which were placed shrouded remains partially or wholly enclosed in wooden sarcophagi. Some of the shafts contained a narrower burial pit at the bottom, in which the burial was placed, and dressed rocks were placed over the body, resting on the rock shelves formed when the burial pit was cut into the base of the shaft. Gypsum plaster was then poured over the rocks, sealing the burial in its tomb. The shaft was then filled to ground level with rocks, sand, and miscellaneous debris and subsequently cemented by halite salt. Other shafts extended to a depth of as much as four m, then branched horizontally into burial chambers of varying sizes and degrees of sophistication in construction (i.e., with rooms, doorways with rock thresholds, and dressed, though undecorated, walls).

In all of the shaft burials hewn through the limestone bedrock, the decomposition of the remains and related organic artifacts was virtually complete. Sealing in the moisture and the atmosphere of the burial by means of the gypsum plaster caps prevented the desiccation of the body, and the artifact recovery from this portion of the cemetery has been limited to pottery, jewelry, and skeletal remains. A small amount of gold, including an amulet, two nuggets, and a gold-filled tooth, also came from burials in the rock-shaft tombs. Burials ranged in number from one in the shallow shafts to twelve in the deep shafts, with burial chambers branching off horizontally from the shaft. We cannot determine whether the large number of burials in one shaft-tomb represented a family burial, opened repeatedly as different members of the family died (both children and adults were buried in the multiple-burial tombs), or whether some catastrophe in the village or family resulted in a mass common burial effort.

After excavating some 17-shaft burial chambers, the team moved across a small wadi (approximately 100 m north) to excavate in an area comprised of aeolian sands, fanglomerates, lakeshore sands and gravels. Burials were encountered near the surface where some have been exposed and removed by erosion, and within the first 5 X 5 m area 22 bodies were recovered between the surface and the depth of 1.5 m. Because the normal factors of Egyptian desert geography and climate (sand and low humidity) played their roles in this region of the cemetery, the condition of recovered artifacts was considerably better than in the limestone shaft burials. In addition to pottery and jewelry, burial wrappings were often well-preserved, and textiles have been recovered in great abundance. During the 1981 season, the excavators recovered some mummiform burials which had articles of clothing neatly wrapped and placed on the face of the deceased. When the corpse was wrapped for burial, after being clothed in linen garments overlaid with an embroidered robe worn like a serape, the extra clothing on the face made the shrouded corpse appear deformed at the head. Of the 123 burials excavated in 100 square meters during the 1984 season, none had the extra clothing wrapped upon the face, although various articles of clothing were placed in close proximity to a body. There were, however, numerous burials which had linen or palm-fiber rope folded to many thicknesses or intertwined into woven designs and placed upon the face just as the articles of clothing were in some of the burials found in 1981. We are quite certain that this aspect of the burial technique found often in the cemetery has religious significance, but we have not yet ascertained its meaning. Many head coverings have been excavated, including a number of hooded robes associated with both males and females, children and adults. The quality of cloth ranges from very coarse material to finely-woven linen, and there are many samples of embroidered designs. Some designs are geometric and others are symbolic, including a design resembling the Egyptian Wedjet eye and some sacerdotal symbols, and there is also some representational art, including one piece of cloth adorned with brightly colored ducks. Some cloth is hemmed and other pieces have fringed edges, with some of the fringe up to 25 cm long. Most of the burials were wrapped with linen ribbon, averaging a little more than 1 cm in width, and containing simple geometric designs in red, black, or white. These ribbons were wrapped in geometric crisscrossing patterns over the shrouded body, often with numerous wraps about the feet and neck areas. Although there is much similarity in clothing and wrapping techniques, individual differences from body to body show that each family (or whoever assumed responsibility for burials) was free to modify slightly the general methods and customs.

The jewelry associated with the burials consists mostly of necklaces, bracelets, and earrings. The materials used in fabricating the pieces include copper, bronze, tin, silver, and a slight amount of gold, as mentioned before. There are also some ceramic bracelets, and a few necklaces and bracelets were made of polished semi-precious stones, held together by single-strand fiber twine or a fabric string. Wire clasps are common for all kinds of jewelry, and one pair of earrings consists of four pendant pearls on each earring, connected to a wire clasp for wearing in pierced earlobes. The jewelry is found mostly with female burials, both children and adults. The observations that most burials do not have jewelry associated with them, and that the artifacts are made from relatively inexpensive and commonly available materials (with a very few notable exceptions which, if anything, tend to emphasize the mean quality of the rest), lead us to the conclusion that burial jewelry in the excavated portion of the cemetery had a sentimental value for the families associated with burying the deceased, rather than religious or commercial value. This may be an argument for the generally low economic status of the people associated with the cemetery, but one may also suggest that religious beliefs precluded the necessity of burying much of worldly value with the dead. The quality and amount of textiles buried with many of the bodies demonstrates that care was taken to ensure that the deceased were properly prepared for interment, and if this world’s goods were thought to be necessary in the post-mortal existence, more such artifacts would be expected to appear in the excavation.

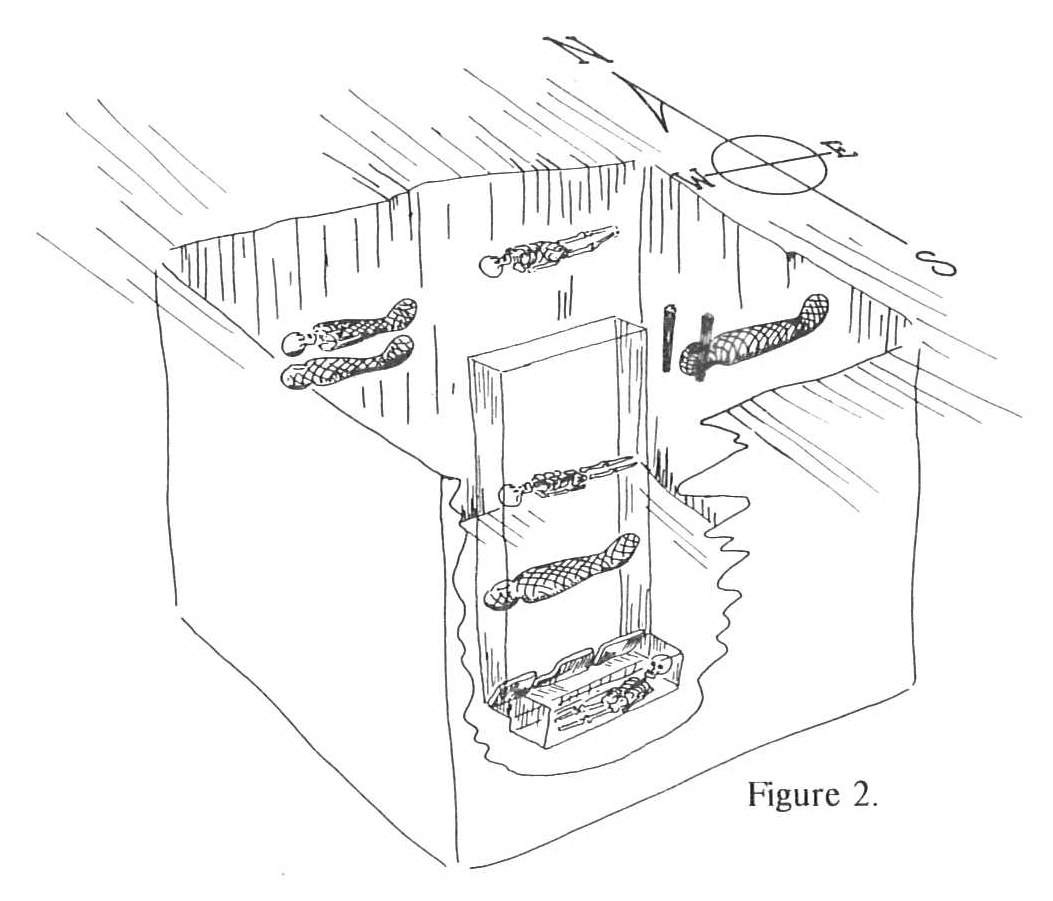

Virtually all the burials in the cemetery are buried on an east-west axis, with variations that correspond to the sun’s amplitude at different seasons of the year. The joint planes of the limestone bedrock happen to run in the same directions, and one could account for east-west burial shafts in that portion of the cemetery by assuming that it was easier to dig shafts along those joint fractures than across or against them. That supposition does not hold in the sandy areas of the cemetery, however, where digging grave shafts would have been equally easy in any direction, and the burials still fall on the east-west axis. We conclude, therefore, that direction of burial was important for reasons beyond those associated with ease of digging, and we further surmise that one might determine the season of digging the shaft by noting where on the sun’s amplitude the axis falls. This would be valid only for the first burial in the shaft, since later burials would be added to the reopened shaft without attempting to align the body with the seasonal amplitude of the sun’s rising. In the shafts dug in the sandy portion of the cemetery, there are as many as five burials from near the surface to the bottom of the shafts, each shaft having an average depth of about three m (see fig. 2, sketch illustrating burial patterns in the sandy portions of the cemetery). However, the burials are not evenly spaced in depth, but sometimes one touches the next above or below, and at other times the burial layers are a meter apart. In some instances children and adults are clustered, as if in family units; in other instances there seem to be no connections between burials in the same shaft. Bundles of reeds used as head markers, pottery, and other artifacts were placed as markers in strata well beneath the surface of the ground, where it would be impossible to see them after the shaft was filled. The reasons for placing such markers beneath the ground have not yet been determined. The burial technique for the first burial, at the bottom of the shaft, differed in most instances from the later (and higher) interments. Angling slightly to the north or south of the vertical shaft the diggers fashioned a burial chamber with dressed stones or mud bricks, often leaning them at an angle from the floor to the wall of the shaft. Only rarely did burials of the upper strata exhibit the same protective measures, and then large amphora shards were used as often as the dressed rocks or mud bricks. In addition to the added effort made for burials at the base of the shafts, one especially noteworthy difference from all other layers must be mentioned. All of the burials from upper layers were placed with the feet at the east and head at the west, suggesting that the person would arise in a resurrection facing east. The bottom layer burials, however, almost always reverse the direction, having the head to the east and feet to the west. Such a significant and total change of technique in one of the most conservative and pervasive ritual activities of man can best be accounted for by a major cultural upheaval in the area. Because the pottery of all strata above the bottom layer dates from the second century C.E. and later (the pottery is often mixed because of disturbances caused by reopening shafts), and because the pottery from the bottom layers of shafts dates from the first centuries BCE and C.E., we propose that the cultural change occurred around the end of the first century C.E. The discovery of two terra cotta figurines of robed figures, one complete and one broken (an angel, the Virgin Mary?) in the burial level just above the bottom of the shafts suggest the arrival and widespread adoption of Christianity. The late first century—early second century C.E. pottery associated with these burials, and a consistency in burial techniques from that level to the present terminus ad quern of the eighth century C.E. at the surface level of the cemetery, lead to the further suggestion that the cultural change which occurred in this area around the end of the first century or the early part of the second century was dominant for at least the next six or seven centuries. Of course this hypothesis must remain somewhat conjectural until inscribed materials or other similarly indisputable artifacts of early Christianity are recovered, but it is at present the best explanation for such a remarkable shift in burial direction, and it also accords with the fact that Christianity became the dominant religion in Egypt for the succeeding centuries. One would thus not expect another major change in burial techniques after the arrival of the Christian faith, and none occurs. The argument for an early arrival and spread of Christianity within Egypt can be made from literary sources, but this may well be one of the first archaeological sources to support that proposition.

As mentioned above, the team excavated 123 burials in 100 square meters during the 1984 season (some had to be left in situ until a future season because they were in the baulk between areas), and the pathology of the bodies done by the three palaeopathologists on the staff yielded considerable information regarding gender, age, stature, and general health. Cranial analysis, including palaeodontology, bone development, especially in the epiphyses of the humerus, femur, and tibia, and determination of pubic width, subpubic angle, and the presence or absence of a lateral recurve were among the field activities of the pathologists in determining anthropological data. Of the 123 burials, 8 were so close to the surface of the ground and so badly preserved or so fragmentary that no meaningful data could be obtained from them. From the remaining 115, however, the following general observations can be presented:

|

Newborn-6 month infants |

7 |

|

6–18 month infants |

7 |

|

18–36 month children |

1 |

|

3–6 year olds |

16 |

|

6–9 year olds |

7 |

|

9–15 year olds |

4 |

Gender is virtually impossible to determine in the children, but the excellent state of preservation of the bodies allowed positive identification of two males in the oldest group (nine to fifteen years).

In the adult population of the excavated areas, there were 31 males and 42 females, totalling approximately 2/

|

15–25 years |

4 males |

13 females |

|

25–35 years |

11 males |

17 females |

|

35–40 years |

7 males |

5 females |

|

40 plus |

9 males |

7 females |

It appears from this sample that infant mortality was about three times as high to the age of six (31 burials) as it was between the ages of six and fifteen (11 burials), and female mortality during the child-bearing years (fifteen to thirty-five) was just double that of males of the same age group (30 to 15). The difference in male and female mortality rates for those older than thirty-five years was negligible (16 to 14), according to this sample. Of course, further excavation in the cemetery will enhance or modify these observations, but they are offered for the four random sample areas excavated in the cemetery.

Not all of the burials had preserved head and body hair, but the characteristics of those which did are rather striking. Eight of the adult males had facial hair, i.e .mustaches and/

The palaeodontology gave considerable information and also raised some interesting questions. The teeth of the infants were still in the bone, as expected, and the development of both baby and permanent teeth was normal for most of the subadult population, with some anomalies such as missing or defective teeth occurring then as they do now. It is in the adult population that dental characteristics are the most telling. Of the 73 adults, 37 had significant periodontal disease, or deterioration of the gum, to the extent that many had lost most or even all of their teeth. Most of those same bodies had some buildup of calculus around the teeth, and both periodontal disease and calculus problems point to the fact that there was little or no practice of dental hygiene, either in dietary selection or by cleaning the teeth and gums. Interestingly, however, there were only 14 adults who had any measurable decay in existing teeth, and most of that decay was minimal, often only one cavity per person. This lack of decay suggests little sugar in the diet, among other possible reasons. Ten adults had extremely good teeth, mostly females, and further analysis must precede conclusions regarding the wide disparity in dental conditions of the adults. The same is true for attrition in the teeth, which ranges from little wear to attrition to the root tips. At present it does not seem adequate to assign the difference in wear patterns totally to dietary causes, such as sand in breads, etc. Some scientists have offered to help in this matter by performing an isotopic analysis of bone fragments in order to determine individual diets more certainly.

This brief survey of the BYU excavation of the Fag el-Gamous cemetery in the Fayum leaves many questions unasked and others unanswered, but as the excavation continues in succeeding seasons, the data gleaned from burials and artifacts will yield increased understanding concerning the Roman-Christian period of Egyptian history, especially in the Fayum.