The Society Islands, or French Polynesia, January 1896–April 1896

Reid L. Neilson and Riley M. Moffat, eds., Tales from the World Tour: The 1895–1897 Travel Writings of Mormon Historian Andrew Jenson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 223–65.

The Society Islands Mission embraces three groups of islands, namely the Society Islands (consisting of the so-called Windward and Leeward islands), the Tuamotu Archipelago, and the scattered Austral Islands, of which Tubuai is the principal member. The Lower Tuamotu conference embraces all the islands of the Tuamotu group lying west of longitude 42˚45´ west of Greenwich, and the Upper Tuamotu conference all the Tuamotu Islands lying east of the meridian named. The Austral Conference takes in all the Austral Islands, though nearly all the Saints reside on the island of Tubuai. As there is only a very few scattered Saints on the Society Islands, and those few all on Tahiti, these islands are not included in any conference organization; but as they are otherwise interesting, and may perhaps become a future missionary field, I will give a few particulars concerning them.

—Andrew Jenson [1]

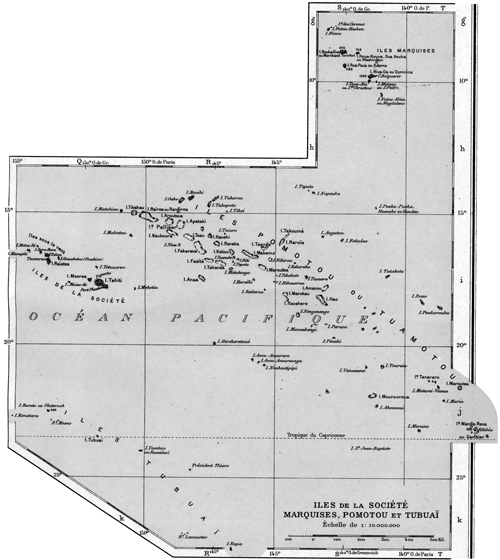

French Polynesia, Vivien de Saint-Martin, Atlas universel de géographie (Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1923)

French Polynesia, Vivien de Saint-Martin, Atlas universel de géographie (Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1923)

“Jenson’s Travels,” February 14, 1896 [2]

Papeete, Tahiti, Society Islands

Thursday, January 23. After giving the parting hand to Elders William Gardner, John Johnson, and R. Leo Bird, I boarded the little steamer Richmond and sailed from Auckland, New Zealand, at 6:10 p.m., bound for Tahiti, Society Islands. The weather was good, and the long voyage commenced under the most favorable circumstances. The course taken was a northeasterly one across the Hauraki Gulf, and we passed into the ocean proper with Cape Colville on our right and the Great Barrier on our left. Just as we were eating supper in the cabin an alarm was sounded on deck, and thinking that a man had fallen overboard or that something serious had happened, we all rushed on deck, when it was discovered that one of the sailors had got his hand entangled in the chain connected with the ship’s rudder. The limb was badly squeezed and wounded, causing the blood to flow freely, but no bones were broken. I had a good night’s rest but felt somewhat lonesome.

Friday, January 24. I spent my first day at sea reading, the weather being fine and the sea smooth. No seasickness was experienced by anyone onboard. At noon our position was 17º17΄ S latitude and 177º41΄ E longitude; the distance from Auckland was 187 and to Rarotonga 1,463 geographical miles. I also became acquainted with the other passengers, of which there were only four, namely, three French pearl merchants and Mr. Edenborough, who is part owner of the steamer. The ship’s crew consists of the captain (Robert G. Sutton, a congenial Scotchman), two officers, nine sailors, three engineers, six firemen, two cooks, and two stewards, making twenty-five men altogether. Adding the five passengers, we are thirty souls onboard, and not a woman among us. The ship is loaded with merchandise for different islands of the Cook and Society groups. There are also five bullocks, twenty sheep, two cats, and two canary birds onboard. The rats, of which there are many, were not counted. The ship registers 750 tons, was built in Dundee, Scotland, about ten years ago, and has the reputation of being an excellent sea boat.

Saturday, January 25. The weather continued fine and the sailing pleasant.

Sunday, January 26. Ditto.

Monday, January 27. Ditto.

Tuesday, January 28. Ditto.

Wednesday, January 29. Ditto, but the weather is getting warmer. I have spent the time onboard so far reading, writing, and conversing with passengers, ship’s officers, and the ordinary sailors, cooks, and all on Utah, the Mormons, true versus false religion, the condition of the world, the prospects of war, and scores of other subjects; but as it was not customary to have preaching or lectures given onboard the Richmond, I did not apply for the privilege of speaking publicly. The voyage has been somewhat monotonous; not a sail or vessel seen of any kind since we left Auckland. One of the most enjoyable features of the trip has been the watching of the beautiful sunsets nearly every evening.

Thursday, January 30. Last night we crossed the line known as the Tropic of Capricorn, and thus the beautiful morning found us watching the limits of the tropics. At noon we were in latitude 22º26´ S; longitude 160º63´ W. We crossed the 180th meridian several days ago, but the ship still keeps New Zealand time. We are now 1,554 miles from Auckland, and it is 96 miles to Rarotonga; the thermometer stands at 82º F in the shade. In the afternoon some of the sailors announced that they saw land ahead, and at 6:00 p.m. the mountainous heights of Rarotonga could be seen with the naked eye by the ordinary mortal. The evening was most beautiful and almost cloudless, and the bright full moon beamed upon us and upon the broad expanse of the ocean in such perfect grandeur that words fail to express the thoughts that passed through my mind in thus gazing upon the beauties of nature. The island came nearer and nearer, and its rugged mountain peaks, which in some instances attain a height of nearly 3,000 feet, seemed to possess a peculiar charm and attraction on this occasion; for hours I never tired resting my eyes upon them. Soon we saw a bright light on the west shore of the island; next we could see and hear the breakers spend their fury upon the coral reef which encircles Rarotonga; and, finally, after rounding a point, we cast anchor off the town of Avarua, about half a mile from the shore, on the north side of the island at 10:00 p.m. There is a little harbor at this place protected from the ocean by a coral reef, through which there is an opening about one hundred yards wide; but the water in the harbor is only deep enough for very small vessels; the Richmond draws too much water to go in, hence our anchorage on the outside. Soon after anchoring, a boat manned by about a dozen natives came out, when it was decided to unload the cargo which we had onboard for this island at once. A whistle, which was understood onshore, was blown, after which a number of boats were soon plying between the ship and the wharf, bringing in the goods; and this work went on most of the night. I landed in one of the first boats, and spent about three hours onshore, where I found nearly the entire population of the town, both whites and natives, gathered around the post office, anxious to receive the mail which the Richmond had just brought. And this was not to be wondered at, for it was nearly two months since the previous mail had reached the island, as the steamer did not make her usual trip in December last. I conversed with a number of people, among whom Mr. Fred J. Moss, the British resident; John J. K. Hutchin, the chief Protestant missionary in the Cook Islands; Henry Nicholas, a New Zealand Maori who is the editor and proprietor of a little newspaper called Te Torea; Mr. Hubert Case, a Josephite missionary; and others. By means of these conversations I obtained considerable information about the Cook Islands, which I believe are very little known to the average American newspaper reader. It was about 2:00 a.m. in the night when I returned to the ship.

The Cook Islands are eight in number and lie in the Pacific Ocean between 18º and 22º S longitude and 158º and 161º W longitude. The most important, the most fertile, and perhaps the most beautiful island of the group is Rarotonga, which is situated in 21º S latitude and between 160º W longitude [sic]. The island is of volcanic formation with mountains rising to a height of nearly three thousand feet, clothed in forest and bush of different tropical varieties. The circuit of the island is about twenty-five miles, and a good carriage road has been made all around it. A few small openings break the coral reef surrounding the island, an advantage which has made Rarotonga the chief resort of shipping and the center of trade for the group. The natives are good ship and boat builders. One of their vessels, a schooner of about 100 tons, recently built entirely by the natives, has already made several visits to Auckland. All their vessels are worked by native sailors; but when they make distant voyages, a European master is engaged. A census of the inhabitants of Rarotonga was taken June 30, 1895, which was the first regular census attempted in any one of the Cook Islands. According to the returns of that census, the inhabitants of Rarotonga numbered 2,454 souls, namely, 1,350 males and 1,104 females. Of this number, 2,121 were natives of the Cook Islands; 186 were born in other Pacific islands, 59 in great Britain, 24 in America, 4 in Germany, 1 in France, 2 in Norway, 8 in Portugal, 11 in China, and 38 (mostly half-castes) in other countries. In the matter of fruit growing, especially oranges and bananas, Rarotonga can hardly be surpassed. The native houses of the island are generally roomy and well built, and are mostly clustered together in villages which are all situated on the seacoast, on the strip of level lands which intervened between the foot of the mountains and the sea shore. The weekly newspaper (Te Torea) is published at Rarotonga by Henry Nicholas, a small four-page folio printed in both English and native in parallel columns; it is highly appreciated by the natives, who take special delight in waiting for it, the editor’s greatest trouble being to find space for their effusions. The other islands belonging to the group are Mangaia, lying 110 miles southeast of Rarotonga; Aitutaki, about 150 miles north of Rarotonga, Atiu, Mitiaro, and Mauke, lying about twenty miles apart and from 100 to 120 miles northeast of Rarotonga; and the two small Hervey Islands (called by the natives Manuae and Vitake) lying between Aitutaki and Atiu.

The Cook Islands are now a federation, which has a regular government, and derives a regular revenue from import duty. The population is about 8,000. The imports for 1894 amounted to £22,433, and the exports to £20,665. Of the imports, £13,151 were from, and of the exports £15,909 to, New Zealand. The chief exports are coffee, of which a very fine quality is grown, copra (the dried coconut), oranges, and general tropical fruits and cotton. Coffee and oranges grow very luxuriantly and without much care. Cotton, owing to low prices, has gone largely out of cultivation, though £1,700 sterling worth was shipped in 1894. Owing to their thorough natural drainage, the islands have a wonderfully good and dry climate—cool and agreeable for a tropical climate. Hurricanes are rare. The wet season lasts only from December to the end of March and has little of the close humid weather that prevails in many South Pacific Islands. The natives belong to the Polynesian race and speak nearly the same language as the Maoris of New Zealand and possess all the qualities, good and bad, of that most amiable of dark-skinned races. The rule of the chiefs among the natives has always been absolute. Each tribe has its ariki (king or queen as the case may be), who is really the leading maturapo, or noble. The ariki is only the first among equals, the mataiapos being the real rulers. Those holding land directly of a mataiapo are called rangatiras. There are no money rents, but an ariki receives certain definite services from the mataiapos, and, through the mataiapos, from the rangatiras. These services are all honorable; but below the rangatiras are the ungas, whose work is of a menial nature, such as pig feeding, cooking, etc. There is no armed body of any kind on the islands, and crime is claimed to be almost unknown, at least on Rarotonga. A very small body of police, or rather watchmen, suffices to keep order, despite the perpetual petty quarrels in which the remnants of old jealousies still involve the natives.

Some of the islands belonging to the group were introduced to the civilized world by the great navigator Captain James Cook, who in 1777 during his third great voyage of explorations around the world [sic]. The islands visited by him that year were Atiu and Mangaia, and the two little islets which he (on first discovering them in 1773) called the Hervey Islands, after one of the lords of the Admiralty of his day. The name “Hervey” has in consequence, often been applied to the whole group, but wrongly. The Cook Islands is the only name by which the group is officially known. Captain Cook never visited Rarotonga, where he might easily have landed and obtained supplies; but he didn’t discover that island. Those at which he touched faced him with unbroken coral reefs and surfs through which no boats could pass, while the natives were drawn up along the shore in menacing array. At that time the natives were cannibals, and in constant warfare with each other. Generally three distinct tribes lived on each of the larger islands, and each tribe was at war with its neighbors.

In 1821, Mr. John Williams, a London Society missionary, came from Raiatea, one of the Society Islands, to Aitutaki and established a mission there. From that island missionary labors were extended to the other members of the group, and by 1825 nearly all had embraced Christianity as taught by the London Society missionaries, and men, women, and children flocked to the schools to learn reading and writing. Soon, also they began to adopt European habits, some of which were good and others bad. Among other things they made for themselves a tasteful style of European dress from European cloth. But while they had flourished and multiplied in numbers under heathenism and in the midst of war, they soon commenced to decrease alarmingly fast under the new conditions of living. Various causes have been assigned for this. When the missionaries first came, the population was estimated at 16,000. Thus, during the seventy years which have elapsed since that time, they have dwindled down to one-half of that number.

Fearful that the islands might be taken possession of by the French or Germans, the natives sought the protection of Great Britain. In 1885, Makea Takau, the ariki va‘ine, or queen, of Avarua, one of the three districts of Rarotonga, visited Auckland, New Zealand, and there saw Mr. Ballance, the minister of native affairs, who, agreeable to the queen’s request, represented the situation in the Cook Islands to the Imperial government. Always on hand to extend her possessions and influence, Great Britain readily responded to the request of the native queen for imperial protection, and on October 27, 1888, the British flag was hoisted on the islands, which were thus placed under British protectorate. The natives were assured that neither their laws and customs then in force nor the governments of their arikis (chiefs) would in any way be interfered with. This agreement has ever since been complied with. In December 1890, a British resident was appointed in the person of Mr. Frederick J. Moss, who, since April 1891, when he finally entered upon the duties of his office, has done a great work in behalf of the people. His office is to advise the natives, to see that no injustice is done to anyone on the islands, and to protect British interest in particular. At the instance of Mr. Moss, delegates were sent from the various islands to Rarotonga to frame a constitution for a contemplated federation and government of the group. The delegates met June 4, 1891, and remained in session till the 10th, when a simple constitution was adopted, leaving each island free to regulate its own affairs but creating a federal parliament to raise a custom revenue and see to mail services and other purely federal matters. The appointment of a chief was one of the greatest difficulties in the way of federation, but finally, after much disputation, the queen Makea Takau was elected to hold the office for life.

Under the constitution adopted, Rarotonga, Mangaia, and Aitutaki send each three members to the Federal Parliament; and Atiu, Mitiaro, and Mauke, who for a long time had been under one local administration, sent three more, making twelve in all. The members meet at Rarotonga in a parliament house which was built for that purpose in 1893. The islands have in great measure laid aside their mutual jealousies, and the business of the government is now carried on without much difficulty. Public schools for teaching English and the general branches of education are also being established, and the steamer Richmond on her present trip brought the first furniture for such a school which is about to be opened at Rarotonga. At present the only taxation is a federal import duty of five percent ad valorem. The sale of stamps by the post office is also a source of revenue. British coin has been the only legal currency since January 1, 1895; but the Chilean dollar is still used by everybody except the government. Originally introduced as equivalent to four shillings, this dollar has fallen in value until it is now passed for two shillings. This is caused by the fall of the price of silver of late years; the bullion value of the Chilean dollar at the present time is only one and a half shilling. It is about twice the size and weight of the English florin, its equivalent as coin and is preferred by the natives on that account. In the Cook Islands there is no definite wages class. All the Rarotonga people have land enough to supply themselves and households with food; but the land is held by the household or family and not by the individual cultivator. They have no rent to pay and work only to obtain such luxuries or enjoyments as they may desire. Those who have to pay rent are natives coming from other islands. They are also the chief workers for wages; but their number is not large. Under these conditions there is no accumulation of wealth, and consequently no reserve of capital. [3]

Friday, January 31. The Richmond resumed her voyage at 4:30 a.m., and when I got up on deck, at 7:30 a.m., the island of Rarotonga was only visible as a little speck against the western horizon. A number of passengers came onboard at Rarotonga, among who were the Josephite missionary Hubert Case and wife, who are returning from an unsuccessful missionary trip to Rarotonga. They brought with a little six-week-old child who was born on Rarotonga. After sailing in a southeasterly direction till noon, land was again seen ahead, which proved to be the island of Mangaia, one of the Cook Islands situated about 110 miles southeast of Rarotonga. About 4:00 p.m. we came to a “standstill” about a quarter of a mile off the west coast of Mangaia, where the main village (Oneroa) of the island is beautifully situated in a coconut grove. Soon we saw a canoe with two white traders and three natives in it push through the breakers and make for the ship. The two traders came onboard and remained with us nearly an hour while the natives took the mail matter to shore and then returned in company with a bigger canoe on which two heavy bales of paper was sent onshore for the London Society missionary who resides on Mangaia and who has a printing press on which he prints occasional pamphlets in the native language. It seemed to require the utmost skill on the part of the natives to steer the canoe through the breakers, who spent their fury on the coral reef which bounds the coast at this point. There is absolutely no consistent landing place on this island; and in stormy weather it is impossible to effect a landing on this or any other part of Mangaia. This makes trade with the island very difficult.

Mangaia is about twenty-eight miles in circumference, is of coral formation, and is covered with tropical vegetation; its highest point is less than 700 feet above sea level. There are about 2,000 natives, most of whom live in three main villages, namely, Oneroa, on the west; Tamarua, on the south; and Avarua, on the east coast. The white population consists of seven persons, namely, three traders, one London Society missionary, and three women. Of the latter, two are the wife and servant girl of the missionary, and the other, wife to one of the traders. The missionary church edifice, a concrete building with thatched roof, is situated on rising ground near the shore and looks quite imposing from the sea; it is said to be one of the finest and largest houses of worship on the South Sea Islands. The London Missionary Society representative on this island apparently has it all his own way. No other religious denomination is represented here, not even the Catholics; hence the inhabitants are governed under church discipline, and so rigged and tyrannical were some of the church laws and rules being enforced a few years ago that complains were finally made to the British resident in Rarotonga, who in October 1893 visited the island in person and effected a change of local government affairs. He found on his arrival that 194 native missionary policemen were employed to preserve order among a population of a little more than 2,000 souls; and that in trying to correct errors in the morals of the people the female offenders were punished much more severely than their male paramours, and that, too, in a manner that would naturally cause the heart of every British and American citizen to burn with indignation. Mr. Moss, the British resident, caused a law to be passed cutting the number of policemen down to twelve and thus compelled 182 able-bodied men to seek other employment. Complaints were also made against the London Society missionary, who was the instigator of the almost inhuman and barbarous punishment inflicted upon the women of the island who were suspected or proven guilty of loose habits; and in due course of time the missionary was called away, and a different man appointed to be his successor. The inhabitants of Mangaia seem to be of a warlike and quarrelsome disposition; each of the three villages of native districts have their own local self-government and do not recognize a common head; nor do they seem to attach much importance to the federation inaugurated under the auspices of the British resident, though they generally send their respective members to the Rarotongan parliament. The traders, who came onboard the Richmond, gave the natives a very hard name morally and also said that they lacked the hospitality and kindheartedness which generally characterize the inhabitants of the South Sea Islands and that they are very selfish and avaricious indeed. The products exported from Mangaia are mostly copra and oranges. Steamers only call two or three times a year, and that during the orange season mostly, while small sailing vessels constantly ply between that and the neighboring islands.

Early in 1845, Elder Noah Rogers visited Mangaia as a Latter-day Saint missionary. He came from the Society Islands and found the language of the Mangaians somewhat different to that spoken on Tahiti; however, he could understand them, and as there was no white missionary on the island at the time Elder Rogers offered to tarry and teach them. But he was informed that two London Society Missionaries in Tahiti (Messrs. Platt and Baff) had written to the natives on Mangaia, warning them against receiving any missionaries or teachers unless they brought letters of recommendation from them. Consequently, they had passed a law to the effect that no white man should live among them. Thus Elder Rogers was compelled to leave without having a hearing, and he proceeded eastward to Rurutu, where he was told a similar story, and found that the missionaries named had written to other islands to the same effect in order to prevent Brother Rogers or any other Latter-day Saint elder from commencing missionary operations in that part of the Pacific. So far as I know no subsequent efforts have been made by any of our elders to preach the gospel to the natives of the Cook Islands nor Rurutu, which latter island lies about 350 miles southwest of Tahiti.

We resumed our voyage from Mangaia at 5:00 p.m. and spent another pleasant night on the briny deep.

Saturday, February 1. The day was cloudy, and it rained a little. When the usual nautical observations were made at noon by the ship’s officers, we were in latitude 20º S and longitude 155º38´ W. Our course was north 50º E. We were 176 miles from Mangaia and 318 from Raiatea. I spent most of the day conversing with the ships’ officers and passengers. [4]

Sunday, February 2. I spent part of the day reading. At noon we were only eighty-seven miles from Raiatea, and early in the afternoon the mountainous outlines of that historical island were seen straight ahead. A little later the islands of Tahaa and Bora Bora, all members of the Society group, were visible a little to the left of Raiatea. At 3:30 p.m. the machinery was stopped in order to make some slight repairs, and we “laid by” for about an hour. When we resumed the voyage, we only proceeded forward slowly, as we would not be able to land at Raiatea till the next morning, owing to the dangerous reef through which we would have to pass by daylight. The night was dark until the moon arose, when the voyage around the south end of Raiatea became very interesting. I stood on the bridge conversing with the captain till a late hour. The ship, after reaching the east side of the island, “stood off and on” till morning.

Monday, February 3. Just after the dawn of day, the Richmond was enabled to run through the narrow passage of the coral reef and soon reached the stone wharf at Uturoa, the main village of Raiatea, which is situated on the northeast coast of the island looking over toward Tahaa, the neighboring island. Both islands are enclosed by the same coral reef, and the four-mile-wide channel between them is not passable for ships, except by very careful manipulations following the various windings or narrow passages through the coral reef. Both islands are of volcanic formation and present a general tropical appearance. Raiatea has about 2,000 and Tahaa 1,000 inhabitants, nearly all natives. On landing at Uturoa, Raiatea, we found the people in their holiday attire, it being Sunday with them, which indeed is the correct time, as this island lies in 151º32´ W longitude from Greenwich. I took a long walk along the road following the beach and conversed with quite a number of natives who could talk a little English. The south end of the island is in a state of rebellion against the French government, and as a matter of protection to themselves the people have hoisted the British colors. It mattered not that a French man-of-war came along a short time ago and shot and pulled down a number of these flags, for as soon as the soldiers had gone away they hoisted them again. The queen of the island has accepted of French protection and keeps the protectorate flag waving from her domicile, which is located somewhat centrally on the east coast. The north end, or the part of the island where we landed, has declared itself French altogether. Thus there are three parties on this little island, of which one hoists the French, the other the French protectorate, and the third the British flag. The natives generally favor the British government, which seems to have done them a flagrant injustice by selling them for a “mess of pottage.” It seems that in the controversy between England and France in regard to their respective New Zealand possessions, England finally agreed to give up her claim on the Society Islands to the French, in consideration of France relinquishing her claim to her infant colony in New Zealand; but it seems that the natives of the Society group, who, for causes pretty well-known, have learned to love the English and hate the French, never were properly consulted in this matter and don’t ever understand the situation now; as they are still expecting Great Britain to come to their rescue and protect them against what they call the aggressions of the French. On the other hand, the French authorities are endeavoring to gain the confidence and good will of the natives by pursuing a mild and lenient policy toward them; and they expect that peace will finally be established on that basis. The neighboring islands of Huahine and Bora Bora have already yielded to French rule, though the former held out for a long time. In order to preserve the peace and protect life and property, about one hundred French mariners are quartered on Raiatea at present. The white population of the island does not exceed twenty-five or thirty all told; most of these are American, British, and German traders; there are only two or three Frenchmen on the island, besides the soldiers. Most of the business of the group is carried on by the British. A son of the late Elder Benjamin F. Grouard, one of the first Latter-day Saint missionaries sent to the Society Islands, is said to reside on this island. [5]

After stopping just three hours at the wharf, the Richmond continued her voyage at 9:00 a.m. and “stood off” in an easterly direction for Huahine, twenty-five miles away. The weather was in an unsettled state, and we encountered a number of squalls, accompanied by heavy rains, before we reached the named island at 11:30 a.m. The steamer came to a stop off a village situated near the northeast corner of the island. A trader came out in a little boat, manned by five bright native boys, to communicate with the ship. From him I learned that there are about 1,500 inhabitants on Huahine, which really consists of two islands, namely, Huahine Nui (Big Huahine) and Huahine Iti (Little Huahine). Like the neighboring islands, Huahine is mountainous and of volcanic formation. The highest point of the island is 1,497 feet high. The loftiest mountaintop on Raiatea is 3,389; on Tahaa, 1,936; and on Bora Bora, 2,339 feet above the level of the sea. From our position off the coral reef surrounding the island, Huahine looks real beautiful, though we noticed the coconut palms were badly blighted. I was told that this blight had been brought over from Tahiti, where nearly all the coconut trees died under that disease years ago, and it is only of later [latter] years that a new growth have matured there. The Huahine people fear that they will have to pass through a similar experience with their coconut trees.

After lying by about half an hour, we continued the voyage passing around the north end of the island. Inside the coral reef at this point is a lagoon abounding with poisonous fish. It is a sort of flat fish with stingers in the back; and a little native boy who accidently stepped on one a short time ago died from the effects of the poison thus introduced into his blood. Near the extreme north end of the island is a very steep sugarloaf-shaped mountain, which is especially noted as the battleground between the French and natives. The French landed their marines from their warships, and the soldiers pursued the natives up the mountain slope, but the latter, who had previously prepared themselves for such an event, rolled heavy rocks down upon the French, who were finally driven back to their ships after losing several of their number. In continuing our voyage we passed outside of the bay or harbor where Captain Cook anchored at different time during his visits to the island between the years 1769 and 1777. Elder Noah Rogers, one of the pioneer Latter-day Saint missionaries to the Society Islands, visited Huahine in the latter part of 1844; but he was rejected by the people; he also visited Raiatea, Tahaa, and Bora Bora, but with the same result. I think he is the only elder who ever visited this group of islands for missionary purposes.

The four islands named are the four principal members of the group which Captain Cook named the Society Islands in 1769; but there are five other islands or system of islands—for there is generally a number of them bearing a common name enclosed by the same coral reef. Thus we have Motu Iti, lying north, and Maupiti west of Bora Bora. Still further west are the coral islands, Mopelia, Bellingshausen and Scilly, the latter being the uninhabited island on the coral reef of which the unfortunate barque Julia Ann, was wrecked en route from Australia to California with a company of Saints in 1855. The present population of the whole group, or the islands named in the foregoing does not exceed 5,000 of whom 600 are on Bora Bora, Tahiti and adjacent islands were not originally included in the Society group.

As we continued our voyage from Huahine we took a southeasterly course for Tahiti, about one hundred miles away. About 3:00 p.m., the island of Moorea was in sight; we passed it in close proximity in the evening on our right; and at 10:30 p.m., we anchored in the harbor of Papeete, Tahiti, after having sailed about 2,400 miles (the way we came) since we left Auckland. As no doctor could be induced to come out to the ship so late in the night though the whistle was blown repeatedly for the purpose, all hands remained onboard till morning.

Monday, February 3. (Tuesday, February 4, by New Zealand time) The Richmond obtained her landing permission early in the morning, and at 7:00 a.m., I put my feet upon the soil of Tahiti for the first time in my life. After some searching I found Elder Frank Cutler, president of the Society Islands Mission, who was waiting for my arrival but had not heard the whistle of the steamer the night before, and consequently knew not of her presence in the harbor till I made him aware of that fact by suddenly ushering myself into his presence. Elder Cutler lives all alone in a small rented cottage in the city of Papeete, boards himself, and sleeps on the floor. He kindly invited me to share his humble home with him if I could put up with his fare. The offer was accepted; and now for the history of the Society Islands Mission.

“Jenson’s Travels,” February 20, 1896. [6]

Sanau, Kaukura, Tuamotu Islands

From February 3, 1895 (the day of my arrival in Papeete, Tahiti, from New Zealand), till the 15th of the same month, I was busily engaged at Papeete, gathering historical information about the Society Islands Mission, [7] assisted part of the time by Elder Cutler. But as no mission record of any kind has been kept so far, it was no easy task to compile history, there being nothing to compile from except a few letters on file from the different elders now in the field, principally for the year 1895. Unless historical data can be obtained from the private journals kept by the respective elders who have labored in these islands, the history of this mission will necessarily be incomplete.

According to the reports which have recently been forwarded form the different elders to the president of the mission, there were 984 souls, including children, belonging to the Church in the mission at the close of 1895. Of these, 57 were on the island of Anaa, 85 on Faaite, 50 on Fakarava, 14 on Aratika, 130 on Takaroa, 32 on Kauehi, 13 on Raraka, 59 on Katiu, 51 on Makemo, 114 on Hao, 8 on Amanu, 3 on Tauere, 73 on Marokau, 128 on Hikueru, 153 on Tubuai, 5 on Rurutu, 6 on Tahiti, and 3 scattered otherwise members. The mission is divided into three conferences, namely the Lower Tuamotu, presided over by Elder Carl J. Larsen; the Upper Tuamotu, with Elder Thomas L. Woodbury as president; and the Austral Conference, over which Elder J. Frank Goff presides. Elders Eugene M. Canon, Alonzo F. Smith, and George F. Despain labor in connection with Elder Larsen in the Lower Tuamotu Conference; Elder Arthur Dickerson is Elder Woodbury’s companion in the Upper Tuamotu, and Elder Fred C. Rossiter helps Elder Goff in the Austral Conference. Elder Cutler himself has had no companion since he succeeded to the presidency of the mission in May 1895. From the foregoing it will be seen that there are nine elders from Zion in the Society Islands Mission at the present time. Of these, Elders Cutler, Woodbury, Larsen, Cannon, and Goff have labored in the mission since March 21, 1893; the others arrived January 4, 1895. During the year 1895, the elders have done missionary work on the following named islands: Anaa, Ahe, Araitika, Apataki, Arutua, Amanu, Faaite, Fakarava, Hao, Kauehi, Katiu, Makemo, Marokau, Raraka, Takaroa, Tahiti, Tubuai, Toau, Taiaro, and Takume.

The Society Islands Mission embraces three groups of islands, namely the Society Islands (consisting of the so-called Windward and Leeward Islands), the Tuamotu Archipelago, and the scattered Austral Islands, of which Tubuai is the principal member. The Lower Tuamotu conference embraces all the islands of the Tuamotu group lying west of longitude 42˚ 45´ west of Greenwich, and the Upper Tuamotu conference all the Tuamotu Islands lying east of the meridian named. The Austral Conference takes in all the Austral Islands, though nearly all the Saints reside on the island of Tubuai. As there is only a very few scattered Saints on the Society Islands, and those few all on Tahiti, these islands are not included in any conference organization; but as they are otherwise interesting, and may perhaps become a future missionary field, I will give a few particulars concerning them.

The Society Islands lie between latitude 16˚ and 18˚ S, and longitude 148˚ and 155˚30´ west of Greenwich, and consists of fourteen islands exclusive of islets. They are divided into the Windward Islands, consisting of Tahiti, Moorea, Maitea or Mehetia, and Tetuaroa; and the Leeward Islands, consisting of Tubuai-Manu, Huahine, Raiatea, Tahaa, Bora Bora, Motu Iti, Maupiti, Mopelia, Bellingshausen (or Lord Howe’s Island), and Scilly. (Map of French Polynesia from 1917 Hachette atlas. All the 1890s maps I could find still used many of the English names the white explorers gave the islands when Jenson used the native names.) The Windward Islands were formerly called the Georgian Islands, and the name Society Islands only applied to the Leeward Islands. The latter were independent states until 1888, when they were taken possession of by the French. The area of the whole group is estimated at 580 square miles, and has a population of about 1,800 at the present time. [8] Nearly all the islands (except the few coral islands and islets) closely resemble each other in appearance. They are mostly mountainous in the interior, with tracts of low-lying and extraordinary fertile land occupying the shores all around from the base of the mountains to the sea, and surrounded by coral reefs. The largest islands are abundantly watered by streams and enjoy a temperate and agreeable climate, considering their location in the tropics. Almost every tropical vegetable and fruit known is grown here; but agriculture is neglected. The native inhabitants belong to the Polynesian race and resemble the Sandwich Islanders very much in character and disposition. They are affable, ingenious, and hospitable, but volatile and sensual. The women of Tahiti are represented by many as being the prettiest met with on any of the Pacific Islands. The practice of tattooing has almost wholly disappeared, and many of the natives pattern now after Europeans in their dress, especially the women, who are now generally in full dress and only show their bare feet and usually uncovered head. The men wear only a shirt and a breechcloth, the indispensable pareu, on ordinary occasions. Copra (dried coconuts), oranges, and lime juice are the principal articles exported. The Tahitian oranges are supposed to be the best in the world. Copra is the general article of barter throughout the islands for groceries and general merchandise, which are imported chiefly from America, France, and New Zealand; but the natives could easily subsist without these imported wares, as the islands produce everything necessary to sustain life, including breadfruit, bananas, fei plantain, yam, sweet potatoes, taro, etc. Both French and Chilean money is used. Taxes and customhouse duties are paid in French money, but Chilean money is used almost exclusively in trade. A Chilean dollar is worth less than half a United States dollar; it is taken at par value with two English shillings and two and a half francs. The denominations in use here are ten cents, twenty cents, fifty cents, and one dollar pieces—all silver. The animal kingdom of the Society Islands is represented by horses, cattle, sheep, goats, hogs, dogs, and fowls, etc. Most of these species were originally imported by the whites.

Tahiti is by far the most important island of the group. It is about thirty-two miles long from northwest to southeast and is an elongated range of high land, which, being interrupted in one part, forms an isthmus about three miles wide which connects the two peninsulas. From a low margin of seacoast, the land rises to a very considerable height on both extremities of the island, where some high fertile valleys intersect the ranges at different parts. The loftiest mountain on the northern peninsula is Orohena, 7,339 feet high. The next in point of elevation are Pito Hiti, 6,996 feet, and Vaorai, 6,771 feet. This last-named mountain is sometimes called the Diadem. From these lofty peaks, ridges diverge to all parts of the coast; they are precipitous and generally narrow, in places a mere edge. The island is nearly surrounded by an excellent broad road called the Broom Road, which, overshadowed with trees, affords a delightful means of visiting the different settlements distributed around it. The code of laws adopted by the Pomares in early days, the punishment for getting intoxicated was making so many feet of this road. Outside the low belt of land at the foot of the mountains, a coral reef encircles the island at a distance of from one-fourth mile to three miles; and within this are several excellent harbors. Tahiti is decidedly a beautiful island and is sometimes called the Eden of the Paape. It is sufficiently high to be seen at forty-five miles distance at sea. Approaching it from the northeast or southwest, it looks like two islands, the low connecting isthmus not being seen. The natives distinguish the two peninsulas of which Tahiti is composed by the names of Opoureonu, or Tahiti Nui (Great Tahiti) and Tiaraboo or Taiarapu or Tahiti Iti (Little Tahiti), united by the isthmus.

Captain Cook in his description of Tahiti, or Otaheite, as he called it, on the occasion of one of his visits, says: “Perhaps there is scarcely a spot in the universe that affords a more luxuriant prospect than the southeast part of Otaheite. The hills are high and steep and in many places craggy; but they are covered to the very summits with trees and shrubs, in such a manner that the spectator can scarcely help thinking that the very rocks possess the property of producing and supporting their verdant clothing. The flat land which bounds those hills toward the sea, and the interjacent valleys also, teem with various productions that grow with the most exuberant vigor, and at once fill the mind of the beholder with the idea that no place upon earth can outdo this in the strength and beauty of vegetation. Nature has been no less liberal in distributing rivulets, which are found in every valley, and as they approach the sea, often divide into two or three branches, fertilizing the flat lands through which they run. The habitations of the natives are scattered without order upon these flats; and many of them appearing towards the shore, presented a delightful scene viewed from our ships especially as the sea within the reef which bounds the coast is perfectly still, and affords a safe navigation at all times for the inhabitants, who are often seen paddling in their canoes indolently along in passing from place to place, or in going to fish. On viewing these charming scenes, I have often regretted my inability to transmit to those who have had no opportunity of seeing them such a description as might in some measure convey an impression similar to what must be felt by everyone who has been fortunate enough to be on the spot.” [9]

Tahiti had 10,113 inhabitants in 1892, of which 4,288 resided in the city of Papeete; the area of the island is 260,000 acres.

Moorea situated about nine miles northwest of Tahiti ranks as one of the loveliest islands of the Pacific, and the harbor of Talu, near Papetoai, is one of the best in the world. The water is so deep close to shore that ships can be tied to a tree on the land. Moorea is a beautiful object as seen from Tahiti, and its beauty is enhanced on a nearer approach; its hills and mountains may, without any great stretch of imagination, be converted into battlements, spires, and towers rising one above the other, and their great sides are clothed here and there with verdure, which at a distance resembles ivy of the richest hue. Moorea has, if possible, a more broken surface than Tahiti, and is more thrown up into separate peaks; its scenery is wild, even in comparison with that of Tahiti, and particularity upon the shores, where the mountains rise precipitously from the water to the height of 2,500 feet. The reef which surrounds the island is similar to that of Tahiti and has no soundings immediately outside of it. Black cellular lava abounds, and holes are found in its shattered ridges, among which is the noted one through which the god ‘Oro is said to have thrust his spear. The inhabitants of Moorea reside upon the shores, and there are several large villages on the south side of the island. By the census of 1892, the inhabitants numbered 1,497. Coffee, cotton, sugar, and all other tropical plants succeed well in Moorea. The island lies in a triangular shape, of which the north side, which runs nearly due east and west, is about nine miles long. The southeast coast is nearly seven, and the southwest eight, miles long. Its area is about 32,710 acres, of which 8,650 are fit for cultivation.

Moorea was discovered by Captain Wallis July 27, 1767, and by him named Duke of York Island.

Maitea, or Osnaburgh Island, is the easternmost of the Society Islands and lies about sixty miles east of the east end of Tahiti, or about one hundred miles from Papeete. The island is high, round, and not more than seven miles in its greatest extent; its greatest elevation is 1,597 feet, and it is in latitude 17˚52´ S; longitude 148˚51´ W. Its north side is remarkably steep. The south side, where the declivity from the hills is more gradual, is the chief place of residence of the natives; but the north side, from the very summit down to the sea, is so steep that it can afford no support to the inhabitants. The eastern part is very pleasant, coconut and other fruit abounding. There were a number of Saints on this island at an early day but none now as far as known.

Tetiaroa is a small, low island, or rather a group of small, low coral islets enclosed in a reef about thirty miles in circumference, lying twenty-four miles north of Tahiti. They formerly belonged to Queen Pomare, of Tahiti, and were inhabited by the poorer people who subsisted on fish and coconuts. The latter still abound. Tahitian ladies of rank made this place one of their favorite resorts, going there, as they said, to improve their complexion by reposing beneath the shade trees; but more frequently, it is supposed that they go to recover from diseases brought about by licentious habits.

Tubuai Manu, or Maiao Iti, formerly also known as Sir Charles Saunder’s Island, is the shape of a foot, hence one of its names, as maiao is “foot” in the Tahitian tongue and iti is “little.” This island is composed of many little islands which gradually have been joined together through the process of nature to make one island, which is about thirteen miles in circumference; its greatest length from east to west is about six miles. In the center a hill, about 160 feet high with a double peak, rises, but the great portion of this land is fertile, and the lower ground abounds with coconut trees. The hills are wooded to the summits, and at a distance the island has much the appearance of a ship under sail. The northeast point is in latitude 17˚38´ S, longitude 150˚ 33´ W, is about fifty-five miles west of Tahiti, and has about 200 inhabitants. It was discovered by Captain Wallis July 28, 1767.

Huahine (Vahine “woman”) is the easternmost of the group, which was called the Society Islands by Cook, who discovered it in July 1769. It is situated about ninety-five miles northwest of Tahiti, is about twenty miles in circumference, and is divided into two peninsulas, called respectively, Huahine Nui, or “large,” and Huahine Iti, or “small.” A strait with shallow water less than a mile wide separates the two islands. Huahine has a very narrow strip of fertile land near the shore, and the mountains, which are not nearly as high as those of Tahiti, more strongly indicate volcanic action and are in some parts cultivated. On each side of the narrow strait separating the two islands the rocks, in many places, rise perpendicular from the water. Owhare Harbor, which was visited by Cook a number of times, is situated on the northwest part of the island. It was here that he, on his last visit, left Omai, the Tahitian native, who had attracted so much attention in England. Huahine formerly belonged to Tamatoa, the king of Raiatea, and was given by him to his daughter, king Pomare’s sister-in-law.

Elder Noah Rogers, one of the first Latter-day Saint Elders sent from Nauvoo, Illinois, to preach the gospel to the Pacific Islanders, came to Huahine in his calling as a missionary in the latter part of 1844; but the people would not receive him. After being rescued from the Scilly Island, on the occasion of the wrecking of the bark Julia Ann in 1855, Elders John S. Eldredge and James Graham, returning to America from missions to Australia, spent about a month at Huahine, waiting for the schooner Emma Parker to get ready to take them to the Sandwich Islands. Undoubtedly they did some preaching at the time. This was in January 1856.

Raiatea, or Ulietea, lies about twenty-five miles to the westward of Huahine and 120 miles northwest of Tahiti. It is about forty miles in circumference, of a mountainous character, is covered with vegetation, and is but too well watered, with cascades, rivers and swamps abounding in all directions. At a distance of one or two miles from the shore, the land is encircled by a coral reef that also encloses the adjacent island of Tahaa. This reef has several small islets on it. Raiatea has seven excellent anchorages on the weather and lee side of the islands. The best of these is the Uturoa Harbor on the northeast coast. It is a reef harbor and has two or three entrances. The soil of the island is exceedingly fertile; exotic fruit trees thrive vigorously, and particularly the fruit of the lime. Raiatea is a beautiful island indeed. Among its historic localities is a valley by the seaside called Opoa, where the chief temple and image of ‘Oro was situated in the days of old. To this place the inhabitants of some of the other islands flocked to offer sacrifices to their god ‘Oro. They brought with them the putrid bodies of persons, who had been hung on trees in their own islands, and left them to be consumed in Opoa. Near this valley is a large cave, the bottom of which has never been found. This place was called “poor night” by the natives, and was supposed to be the place of departed spirits. There is a legend among the people to the effect that a cruel king of Raiatea, who was curious to examine this cave, ordered his subjects to let him down by a rope. They obeyed; but when they found their chief in their power, they let go the rope and left him to perish.

Elder Noah Rogers visited Raiatea as a missionary in 1844 but was rejected by the people. Elder John McCarthy immigrated to America from Australia, visited Raiatea late in 1855, or early in 1856, after being shipwrecked in the ill-fated Julia Ann on the Scilly Island. He remained two weeks and baptized a Spaniard by the name of Shaw whom he ordained an elder, but what became of that elder I have been unable to learn.

Tahaa, which is forty miles in circumference, is sometimes called the twin sister to Raiatea, as it is enclosed in the same coral reef. The water between the two islands is smooth and only about two miles in width, and both are surrounded by a great number of anotus, which rest upon the coral reef. Tahaa is about half the size of Raiatea and is not so fertile. Captain Cook visited this island in his boats in 1773; and Lieutenant Pickergill was sent around it by him in a boat in 1773.

Bora Bora is distinguished by a very lofty double-peaked mountain, which rises in the midst of and reaches far above the surrounding hills. It is crowned by a square piece of rock which appears as if placed there by human hands, though no human foot has ever reached the summit. Bora Bora is about eight miles northwest of Tahaa, to which it is inferior in extent, but the reef with which it is surrounded is nearly full of islets, much larger than those which are scattered among the rocks that enclose Raiatea and Tahaa. Bora Bora is more rude and craggy than the rest of the Society Islands. Its eastern side has a barren appearance, the western is more fertile; a low border which surrounds the whole, together with the islands on the reef, are very productive. Its earliest inhabitants are said to have been malefactors, banished from the neighboring islands. Caption Cook did not land here upon his first or second voyage, and in 1777 he was prevented from anchoring in the harbor by contrary winds. On its west side is Vaitape, the port of the island, to which the distance from Tahiti is about one hundred and fifty miles.

Bora Bora, as well as Huahine, Raiatea, and Tahaa, was visited by Elder Noah Rogers in the latter part of 1844; but the natives, influenced by sectarian ministers, would not receive him as a Latter-day Saint missionary. I believe no attempt has been made by any of our Elders to preach on Bora Bora since 1844. According to French official reports, the island of Bora Bora has about 600 inhabitants at the present time. Huahine has about 1,300 and Raiatea and Tahaa together about 3,000 inhabitants.

Motu Iti is the northernmost of the Society Islands proper and consists of some very small, low islets, connected by a reef, about ten miles north northwest of Bora Bora, to which it belongs. It has no permanent inhabitants; turtles abound.

Maupiti, or Marua, is the westernmost of the Society Islands proper.

It is forty miles northwest of Raiatea and is distinctly visible from the lower hills of that island. It is about 170 miles northwest of Tahiti. The island is composed of hills wooded to their summit and occasionally crested by coconut trees but presenting ragged and mural cliffs to the seacoast, especially one rocky mass on the southwest side, which rises 700 feet above the sea, resembling the ruins of a gigantic castle. The population of the island is small; the principal village is situated on the southeast side. The island is surrounded by a coral barrier reef at a distance of about three miles, enclosing numerous small islets covered with coconut trees. The island, which is seldom visited by foreign vessels, is in latitude 16˚26´ S, longitude 152˚12´ W.

On learning of the disaster of the Julia Ann on the Scilly Island reef in 1855, the king or chief of Maupiti, in response to a petition by Elder John McCarthy and others, dispatched two little schooners to the Scilly Island for the purpose of talking off the castaway “emigrants,” but on arriving there they found that Captain Pond, who had chartered the schooner Emma Packer at Huahine, had been there twelve hours before and had taken the people away. Elder McCarthy then returned with the schooners to Maupiti, where he commenced to preach the gospel. He found favor with the King Tapor and baptized the king’s interpreter, Captain Celano, a Maltese by birth, who could speak seven languages. Brother McCarthy ordained this man an elder and was enabled through him to preach the gospel to the natives, who seemed favorably impressed by his testimony. After about three weeks’ stay on Maupiti, Elder McCarthy sailed for the island of Raiatea. This was in December 1855.

Scilly Island consists of a number of very low islets, or motus, lying on a coral reef which measures about fifteen miles in circumference. The easternmost motu is in latitude 16˚28´ S, longitude 154˚30´ W, or about 185 miles west from Raiatea and 300 miles northwest of Tahiti. Besides the circular reef composing the island, a hidden reef extends in a westerly direction for many miles, and the whole reef system constitutes a very dangerous locality for navigators. It was on the hidden reef on the west and about twelve miles from the island reef that the ill-fated bark Julia Ann en route from Australia to America with a company of Saints was wrecked October 3, 1855. On that sad occasion two women and three children were drowned and the survivors compelled to spend several weeks (most of them just two months) on the uninhabited island subsisting on turtle and brackish warier. They were finally taken off by the Emma Packer, a schooner, which Captain Pond had chartered for the purpose at Huahine. The Scilly Island was discovered by Wallis in 1767.

About fifty miles southeast of Scilly Island lies Mopelia, another coral island about ten miles long by four broad, discovered by Wallis in 1767; and about forty miles northeast of Scilly is Bellingshausen Island, which is also a low, uninhabited coral island, triangular in form and richly covered with tropical vegetation. These three last-named islands do not properly belong to the Society group, but as they belong to no other group geographically and they are now classed as French possessions and counted by French officials as members of the Society Islands, I have also described them under that head in this article.

“Jenson’s Travels,” February 22, 1896 [10]

Island of Manihi, Tuamotu Archipelago, South Pacific Ocean

Saturday, February 15. Elder Frank Cutler and I, intent upon a missionary and historical tour to the Tuamotu Islands, boarded the fine schooner Teavaroa, Henry Mervin, supercargo, at 11:00 a.m., and at 12:00 noon we set sail and left the Papeete wharf, island of Tahiti. The wind being contrary and very little of it at that, it took us two hours to get out of the harbor, having to tack a number of times. The American mail vessel Tropic Bird had most of her sails set as we passed her ready to go to sea, but could not get out against the wind. The island of Tahiti and also the neighboring island Moorea, with their grand, lofty mountains, look grand and imposing from the sea. Having cleared the reef at 2:00 p.m., we soon struck the trade wind, which filled our sails nicely and enabled us to take a northeasterly course. There was quite a heavy swell on the ocean which caused everybody onboard who were not sailors to reel and stagger; and, contrary to my fond expectations, I got seasick and fed the fishes several times during my first night on the Teavaroa. In fact Elder Cutler and I spent a miserable night lying on the cabin deck and trying in vain to sleep; it was too warm and sickly in the cabin below.

Sunday, February 16. We had kept a northeasterly course all night, and at 10:00 a.m., we sighted the island of Makatea straight ahead. Failing to make the windward side, we passed its extreme northwest point within a distance of 300 yards at 2:00 p.m., which gave us an excellent opportunity of studying the formation and vegetation of the island. Makatea is an uplifted coral island situated in latitude 15º52´ S; longitude 148º20´ W of Greenwich, or about 125 miles northeast of Tahiti; it is about five miles long by four wide and produces copra, beans, sweet potatoes, etc., which latter products the natives have commenced to import to other islands. Makatea, unlike all the other Tuamotu Islands, is elevated in the center, its highest point being 250 feet above sea level and is covered with a brush called tamanu. The only village on the island is situated on the northeast coast; the inhabitants, numbering about 150, are now nearly all Josephites. The island has recently been visited by Elders Eugene M. Cannon and Alonzo F. Smith, but with what success I do not know at present.

The west coast of Makatea was very interesting to look at as we sailed by; its nearly perpendicular walls rise to a height of about one hundred feet (perhaps more) and they abound with caves and numerous strange formations—the work of corals and the actions of water during the past centuries. After leaving Makatea, we continued our voyage in the direction of Rangiroa.

Monday, February 17. The early-morning hour found us beating off the south coast of Rangiroa, which is the largest of all the Tuamotu Islands extending as it does from northwest to southeast about forty-two miles and is twenty miles wide on an average. Its center is situated in latitude 15º9´ S and longitude 147º40´ W of Greenwich. This island, like most of its sister islands, consists merely of a coral reef, which here and there is covered with trees. Some of these patches are several miles long and from a few yards to half a mile or more in width; but others contain only a few acres, some of them as seen from a distance puts one in mind of a huge bouquet of flowers. The lagoon inside the reef abounds with pearl shells for which the natives dive whenever the lagoon is open for that purpose. Coconut trees are plentiful on this island, and the export of copra amounts to something like 400 tons a year. Rangiroa, which translated means “long heaven,” was one of the islands of the Tuamotu group where Elder Benjamin F. Grouard and other elders at an early day preached the gospel with success, and branch organizations were kept up till about 1885, when the Josephites interfered and caused the natives to identify themselves with their organization.

During the day, Teuira, the Hawaiian captain of the Teavaroa, related the following incident in his life. Sometime in 1882 he sailed from Tubuai bound for Tahiti as master of the schooner Alura Toeran, having twelve souls onboard, including himself, all natives. There were eight men, three women, and one child. The schooner was a vessel of seventeen tons register. After proceeding about 135 miles from the port of embarkation, a terrific whirlwind struck the vessel and capsized her, spilling most of the passengers in the ocean. The captain, not being on duty on time but asleep in the cabin, was not aware of what had happened till he felt his feet and soon his whole body in the water. He made a spring for the cabin door and soon found himself together with nine others sitting on the keel of the vessel, which by this time had turned completely upside down. But two of the women were missing, one of whom was the captain’s own wife. Though they were supposed to be drowned already, Teuira, who like most natives of the Pacific Islands is a good diver and swimmer, dove under the vessel and tried to force his way into the cabin, but as one or more heavy boxes had rolled against the door from the inside he was at first unable to effect an entrance, but succeeded, after diving several times in pushing the door open, when he found the two women standing in water to the neck, being just able to breathe. Bidding one of them to follow him at a time by diving for the door, he succeeded in pulling them out from the interior of the vessel and then helped them to a position on the keel. Thus all hands were saved so far, but how to proceed next was a question of vital importance. Most of the others seemed to have lost their presence of mind and could think of no means of escape from the doomed vessel, but the captain, unaided by the others, set to work to unfasten the little boat which was secured to the deck or rigging of the vessel deep under the water. This he did by diving down repeatedly and stopping under the water as long as possible, working at the ropes. At length his toil was rewarded, and to the great joy of all the little craft, scarcely ten feet long, was floating on top of the water. To bail it out was an easy task; but after eight persons had got into it, it commenced to sink, thus showing that it was altogether inadequate to carry away any more than half of the shipwrecked people, and even that number would by no means be safe in case of stormy weather and a rough sea. Something else must yet be done in order to save all. Though considerably exhausted from his previous diving, the captain renewed his labors under water and succeeded, after going down many times, in unfastening the booms of the ship and bringing them together with some of the sails to the service [surface]. All hands now went to work assisting the captain in constructing a sort of craft by tying the two booms together with three ropes in such a way that the boat occupied a central position between them, being lashed to the timber, and thus prevented from sinking. Secured in this manner, all the people after deciding to make their way to Tahiti if possible, left the capsized vessel at 6:00 p.m. on a Friday evening, the capsizing having occurred in the morning. A woman’s shawl fastened to a short stick or paddle which was raised from the raft served the purpose of a sail, the canvass taken from the schooner having been used to wrap around the boat. Being exposed to the mercy of wind and waves, the unique raft was kept heading in the direction of Tahiti for three days, but as the wind was contrary, that island was about as far off at the end of that time as when they started out. The wind blowing in the direction of Rurutu, it was now decided to change course and head for that island; and after suffering terribly from want of food and water, a single box of oranges being the only eatables secured from the schooner, Rurutu was finally reached on the Saturday, just eight days from the time of the shipwrecking. As the raft was thrown violently against the reef, all the people were cast into the sea, but they had strength enough left to swim to shore, and thus they were all saved. The people of Rurutu treated the unfortunate navigators with great kindness, and after recuperating for several days, they were taken back on another vessel to their own island, Tubuai. As an appreciation of bravery and true merit, Captain Teuira was subsequently awarded a gold medal by the French government, of which he appears to be justly proud.

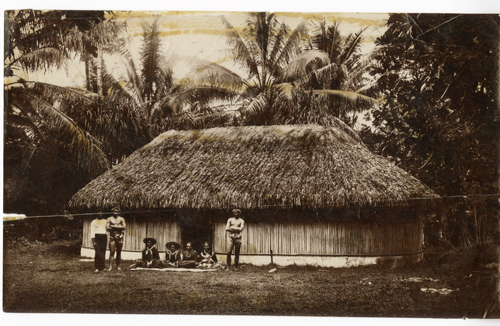

Tuesday, February 18. Early in the morning the island of Kaukura was seen straight ahead, and we were making good speed towards it when the wind suddenly died out and left us drifting helplessly at sea. About noon, however, a breeze sprang up which enabled us to reach that particular motu, or part of Kaukura which is known as Raitahiti, where some of the people are located temporarily to gather and dry coconuts for the markets. At 2:00 p.m. the ship’s boat was launched, and Elder Cutler and I landed together with a part of the crew who were going to work with the copra. The passage over the reef at this point is a dangerous one, and several accidents have happened of late both to men and boats; but the weather being good, we got safely in. On landing we met a number of natives, who greeted us warmly and invited us into one of their huts, where we were given coconut milk to drink. We then engaged in long conversations with some of the leading men present, among whom were Tetuarere who presides over the Josephite organization on the island of Kaukura. Elder Cutler talked a long time to the people who gathered to see us, and they all seemed very much pleased with what they heard; and when we left, they presented us with two baskets of coconuts and two live chickens. We returned to the ship after sundown.

The island of Kaukura is twenty-six miles long from northwest to southeast, and ten miles broad on an average. Its west point is in latitude 15º43´ S, longitude 146º50´ W, and about 195 miles northeast of Tahiti. It has a boat entrance near the northwest end. About two hundred tons of copra is exported from the island per year. The lagoon also abounds with pearls, but it is closed at present. Among those Elder Cutler and I met onshore—the two white traders of the island—one (Peter Peterson) was a Shaleswick Dane, the other (George Richmond) an American from the state of Massachusetts. No schooner or other vessel from Tahiti having called for a long time, the island had been short of provisions for over two months, and even the traders asserted that they had been without bread for three weeks. All the flour consumed here is imported from San Francisco and is sold by the local traders at the rate of seven Chilean dollars per 100 pounds. Mr. Richmond has married a native wife with whom he has twelve children. The other man simply lives with a native woman.

Wednesday, February 19. The shipping of copra was continued from yesterday, and it took all day before the crew finished their labors. In the evening all the men came onboard, and the ship stood off and on all night as she had done all day. Elder Cutler and I, remaining onboard, spent the day reading and writing. The day was exceedingly hot, and life on the Teavaroa that day was in consequence anything but pleasant. About fourteen tons of copra was taken onboard. Copra has only been known in the Pacific Ocean during the last twenty years. It was first introduced by Godeffroi and company, the well known Hamburg House, who laid the foundation of the German interests in the South Seas. The introduction of copra changed the face of the oil trade and gave a new value to the low atolls, or lagoon islands, which are the coconut’s natural home. The kernel of the nut is dried and sent to Hamburg or other European ports, where the oil is extracted, and the refuse sent as oil cake to England. The cocoa palm loves the sea air, and the salt spray; and on these low atolls it gets both. The absence of grass or other competing growths makes the cost of cultivation small. The cost of gathering the harvest is also easy. The fruit, which ripens on the tree, is collected and husked when it falls; and the kernel, after being dried in the sun, is cut up and loaded in bulk in the ship’s hold. The natives are very skillful in the preparation of copra, and they seem to like the work connected with it.

Thursday, February 20. We awoke early enough to behold the beautiful sunrise, at which time we were only half a mile off Panau, the only village of any importance on the island of Kaukura. At 6:00 a.m. Elder Cutler and myself landed with the ship’s boat, which brought goods onshore. The boat landing here is quite safe, and consists of a break in the reef through which a small vessel can approach the dry sandy beach within one hundred feet or so. As soon as we landed, the inhabitants of the village flocked around to shake hands and bid us welcome, and we were at once conducted through the main portion of the village to the house of Teura, the native trader whom we had met before on the neighboring motu. The principal men of the island soon gathered, or rather followed us there, and we now spent about an hour in lively conversation, telling them something about Church history and showing them views, specimens of rocks from some of our temples, etc., which seemed to interest them very much. When we were ready to leave, some of them made us presents of shells and said they were much pleased with our visit.

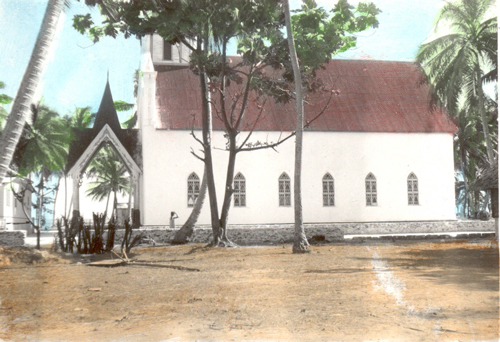

The village of Panau occupies nearly the entire surface of the motu known by that name, which is about half a mile long by a quarter of a mile wide and is covered with young, thrifty coconut trees. These have all been planted since the cyclone in 1878, when the entire island was bereft of its fine growth of trees and brush of every kind; also the whole village was destroyed, only one house being left standing, and the ruined condition of that one was pointed out to us as we passed. The most imposing structure of the village is the Catholic church, a stone building surmounted with a little spire, which presents a fine appearance from the sea. The meetinghouse which the Josephites are using is a plain lumber structure with board shutters instead of windows. This also was built after the cyclone, mostly from the material which had been in the former one that was blown down by the storm. The main thoroughfare of the village is lined on both sides with coconut trees, and the houses, many of which are built in European style, lie scattered somewhat irregular on both sides of the alley. Before the cyclone the island contained over two hundred inhabitants; now it has scarcely much above half of that number according to the best information we could obtain, as one hundred persons perished during the storm. This catastrophe need not have happened; but when the natives saw their island almost inundated by ocean water which the terrific wind blowed [sic] over it, and their coconut trees pulled up by the roots or break square over in other instances, some of them seemed to lose their presence of mind and ordinary judgment, as they took to their boats and pushed off onto the lagoon; but of course no boat could live upon the water in such weather, and the consequence was that all those who embarked were drowned, while all who remained on land escaped with their lives, though they lost nearly all their property. No other island of the Tuamotu group suffered in that storm to such an extent as Kaukura, as the center or the heaviest part of the cyclone seemed to strike it with all its force.

Among the natives with whom we conversed at Panau was an old man by the name of Tehopea, who claimed to have met the late Elder Benjamin F. Grouard on the island of Rangiroa about the year 1852, or just before that elder returned to America. He also said that there was a continuous branch of the Church on Kaukura from the time the American elders left till the Josephites came.

About 7:30 a.m. we returned to the ship, which about half an hour later set sail for the neighboring island of Arutua about twenty miles distant. About 10:00 a.m. the treetops of that island were seen ahead; but as the wind was contrary, it took us till late in the afternoon to reach a point off Rautini, the name of that particular motu of Arutua where the village stands and the people live. About 3:00 p.m. the ship’s boat was launched and left for the village. I jumped in at the last moment, but Elder Cutler, who was not through with his toilette, was left behind. As the wind blowed toward the island, the ship dared not go in close to the reef, hence the crew had to row the boat a long distance to the place of landing, and as the sea had a very heavy swell on, the rowing was difficult, and we were tossed about considerably before we got through the passage and reached the stone wharf in front of the village. Here I was in a fix without an interpreter, as the few Saints temporarily located on the island while fishing for shells soon gathered around me at the house to which I was first conducted; but the native brother who was our fellow passenger and who also landed could talk a very little broken English, and I got along, as well as I could with his services. I also introduced myself to Mr. Carl Hanson, a Swede, and one of the traders of the island, from whom I obtained several particulars in regard to the island of Arutua, which is nearly circular in shape and measures about fifteen miles across, lagoon included in most places. The pass which our boat came through is the only passage which connects the lagoon with the ocean; it is deep enough for vessels of twenty or thirty tons’ burden only, and as the current often runs very swift, and it is on the southeast or windward side of the island, the entrance is very dangerous. The little village, which is nearly hidden from sight in the coconut grove, lies on a small motu on the right-hand side as we enter. The reef around the lagoon is pretty well covered with vegetation, except on the west and south, where there is considerable bare reef. Arutua is noted for its fine pearl shells, some of which are marvels for size. In one year alone (1886) fifteen tons of shells were fished out of the lagoon; but this season has been an unsuccessful one and all the transient divers are preparing to leave, as they cannot find shells in paying quantities. The cyclone of 1878 destroyed most of the trees of Arutua; hence the present beautiful growth of coconut trees consists mostly of new plantations. Arutua is about 215 miles northwest of Tahiti. That and the two neighboring islands Kaukura and Apataki were named the Palliser Islands by Captain Cook.

Before I left the village, Marerenui, a brother in the Church, made me a present of a fine pair of shells, and we returned to the ship about sundown, reaching it with much difficulty, as the rowing had to be done against the wind and high rolling waves.

Friday, February 21. We had sailed to and fro all night, and when the light of the morning dawned upon us we were coasting along the west line of Apataki, but just as the crew was getting the boat ready to go ashore, a drenching rainstorm set in, which continued all day, and thus we were compelled to spend a very dull day in an inactive manner at sea. Several squalls struck the vessel, which somewhat relieved the monotony; but the real excitement of the day was the catching of a large swordfish (on the fish line) which had been following the ship for some distance. The fish, which weighed several hundred pounds and was a beautiful specimen of his kind, was successfully hauled alongside the vessel, where he was speared or harpooned almost to death; but just as the crew, which was considerably excited, was in the act of lifting him bodily onboard, the fish made one last desperate struggle and thus jerked himself loose from the hands that held him and was lost as he sank in the ocean. It was too bad. We could have got him just as well as not had the crew not been so excited that they neglected to secure him with ropes before attempting to haul him onboard. In the afternoon, notwithstanding the rain, Mr. Mervin and part of the crew landed in the boat. On their return it was decided to sail at once for the island of Manihi, distant about sixty miles in a northerly direction. Consequently, about sundown we set sail for that island, and the wind being favorable and the weather now being good, we sped toward Manihi at the rate of ten miles an hour during the night.

“Jenson’s Travels,” February 29, 1896 [11]

Teavaroa, Takaroa, Tuamotu Islands