Missionary Service

Bruce A. Chadwick, Brent L. Top, and Richard J. McClendon, “Missionary Service,” in Shield of Faith: The Power of Religion in the Lives of LDS Youth and Young Adults (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2010), 265–94.

Each year, nearly 30,000 Latter-day Saint young adults leave their homes to serve missions in various countries throughout the world for the purpose of converting others to the tenets of the Church. Once these young adults return home from their missionary service, many go on to further their education, begin a career, marry, and establish a family.

Returned missionaries are a unique group in the Church and are often a point of interest in family, Church, and other social settings. Parents, for example, note the challenges their returned missionaries face as they make the transition from the mission field to the home. Parents sometimes observe a raised level of stress that occurs as their sons or daughters shift from the focus of the mission to the focus of school, work, and dating.

Ward and stake leaders also have an interest in returned missionaries, often giving them counsel and encouragement as well as assigning them the most suitable Church callings during the transitional time. President Gordon B. Hinckley (2001) emphasized the importance of this duty to Church leaders when he said: “I am satisfied that if every returned missionary had meaningful responsibility the day he or she came home, we’d have fewer of them grow cold in their faith. I wish that you would make an effort to see that every returned missionary receives a meaningful assignment. Activity is the nurturing process of faithfulness” (p. 65).

Missionary service and returned missionaries are also a point of discussion in the day-to-day conversations among Latter-day Saints. Statements or questions such as “He’s a returned missionary,” or “She went on a mission,” or “Did you serve a mission?” can often be heard wherever Church members are gathered.

Why are Latter-day Saints interested in knowing if someone is a returned missionary? One reason may be that when Church members learn that someone has served a mission, they naturally see that person differently. People somehow expect more of returned missionaries—that they should be more spiritually grounded, that they should be leaders in the Church, that their homes and families should be stable, that they should be successful in their schooling and careers.

These assumptions, although commonly and culturally accepted, unfortunately may not always be the case. One bishop in a BYU singles ward observed a number of returned missionaries who regretted the “loss of the Spirit” since returning from the mission field, including some whose Church attendance gradually dropped off until they eventually disappeared from the landscape. Others had dropped out of school; were working in low-paying, dead-end jobs; were waiting longer to marry; and were alienated from their families. Some had experienced severe depression during their first two years home, while others had committed rather serious sins, including involvement with drugs, alcohol, pornography, and sexual transgressions.

Are these behaviors isolated cases or part of an emerging pattern of secularization among returned missionaries in the United States? We set out to further investigate this and other questions by surveying 5,000 returned missionaries scattered across the United States, hoping to gain a more accurate view about how they are doing—both in the early stages of their return home and the later stages as they settle into adulthood.

Three general questions were assessed in this study. First, how are returned missionaries doing in their current spiritual, family, and educational pursuits? We answered this question by looking at a number of demographic factors of returned missionaries. These include the educational attainment, socioeconomic status, family life, and religious experiences of those who had been back from their missions 2, 5, 10, and 17 years, respectively. The original strategy was to look at those who had returned from their mission 15 years before our study, rather than 17 years. However, a two-year adjustment was made because missionaries who returned 15 years before our study served for only 18 months. We thus selected the 17-year group who served for 24 months, the same length of time as the 2-, 5-, and 10-year groups.

Assessing these areas in the lives of returned missionaries provided a barometer on how successful they are as they venture out in the various roles of life. Part of this assessment was to also identify similarities and differences between the demographic traits of men and women. Duke and Johnson (1998) surmise that for Latter-day Saints, “The experiences of men and women are quite different and have a significant impact on the way they feel and worship.” Thus, we sought to understand the unique differences and similarities in life outcomes of returned-missionary men and women.

A second question we set out to answer is whether or not more recently returned missionaries are as committed to gospel values and Church activity as those who returned from their missions decades ago. Unlike most recent research on returned missionaries, which has mainly looked at the impact of the mission experience itself, our objective here was to examine if social change in the United States over the past several decades has influenced returned missionaries’ religiosity in some way (Thomas, 1992; Roghaar, 1991).

Three decades ago, Madsen (1977) found that returned missionaries were doing very well in their religious activity. He summarized his findings by saying that “the vast majority of returned missionaries attend Church meetings regularly, possess a current temple recommend, serve in Church callings, pay tithing, and observe the Word of Wisdom” (abstract). We used Madsen’s study as a baseline to compare the religious behavior and marital status of returned missionaries in our sample, thus allowing us to observe any changes over the past 30 years.

One of the theoretical foundations for hypothesizing whether returned missionaries of today should be any more or less religious than those studied back in the 1970s comes from the secularization thesis, a commonly discussed theme in industrial society. Scholars who accept this thesis propose that religious commitment in American society has been in a decline over the past several decades (Lechner, 1991). They believe that as modernization and science have increased in the United States, people are replacing faith in God with belief in science. Taking this view, we might predict that the religiosity of returned missionaries is also in decline and that our sample of returned missionaries would have lower religiosity than those who returned 30 years ago.

On the other hand, those who reject the secularization thesis argue that despite science’s increasing influence, a religious revival is occurring and religious devotion in the United States is as high as it has ever been (Caplow, Bahr, & Chadwick, 1983; Stark & Iannaccone, 1992; Warner, 1993). If this is true, we would anticipate that religiosity among LDS returned missionaries has actually increased over the past three decades or at least has remained steady.

Finally, a third question we desired to answer was, What things will help returned missionaries stay active and committed to the gospel after they return home? We assessed this with two approaches. First, we asked those in our sample to report their own insights about post-mission adjustment challenges as well as what they and the Church can do to help with that adjustment. Second, because private religiosity is a significant part of a Latter-day Saint life, we applied statistical modeling procedures to identify the most important factors that lead to private religiosity in adulthood among returned missionaries. Private religiosity involves such things as reading scriptures, personal prayer, and thinking about religion. The data collection procedures are described in detail in Appendix A.

Returned Missionaries: Socioeconomic Status, Family Life, and Religiosity

It is commonly believed that missionary service produces not only a strong testimony but also a foundation for success in a number of other areas of their lives. Based on our findings, there is solid evidence supporting this claim.

Socioeconomic status. Church leaders have consistently stressed the value of preparing for life’s work through a proper education. President Hinckley (2001) counseled youth and young adults of the Church: “You are moving into the most competitive age the world has ever known. All around you is competition. You need all the education you can get. . . . You belong to a Church that teaches the importance of education. You have a mandate from the Lord to educate your minds and your hearts and your hands” (p. 4).

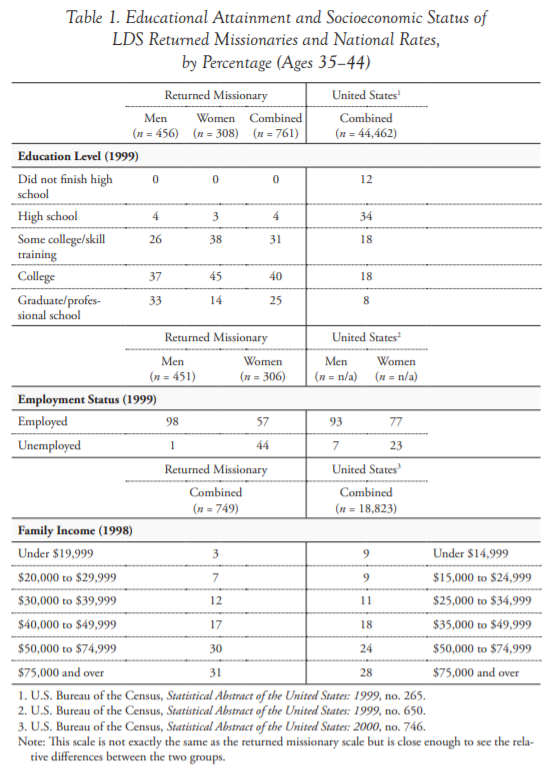

How are returned missionaries doing in this endeavor? We found 95% of them had at least some college or skill training (see Table 1). Among those who had been back from their missions the longest (17 years), 37% of the men and 45% of the women had completed an undergraduate degree. Another 33% of the men and 14% of the women had earned an advanced degree. The rate for both men and women combined in these two categories is 40% with an undergraduate degree and 25% with an advanced degree. These rates are considerably higher than the national average. For example, among those in the United States of about the same age (35 to 44) in 1998, only 18% of men and women combined had a college degree, and an additional 8% had an advanced degree (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1999, no. 265).

Two other important indices of socioeconomic status are employment and income. Returned missionaries rank relatively high in both. We found that 95% of the men and 63% of the women were gainfully employed at the time of this study. Employment among the 17-year group was at 98% of the men and 57% of the women (see Table 1), while the national rate for men of the same age group was at 93% and 77% for the women (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1999, no. 650). The lower employment rate among returned-missionary women when compared to other women in the United States is not surprising given the Church’s view that the primary role of mothers should be centered on more domestic responsibilities.

The higher levels of education found among returned missionaries is evident in family income, which was a little above the national average. Eighty-five percent of the men in the 17-year group and 67% of the women (78% combined) made $40,000 or more in 1998 (see Table 1). By comparison, 70% of families in the United States made $35,000 or more in 1998 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000, no. 746).

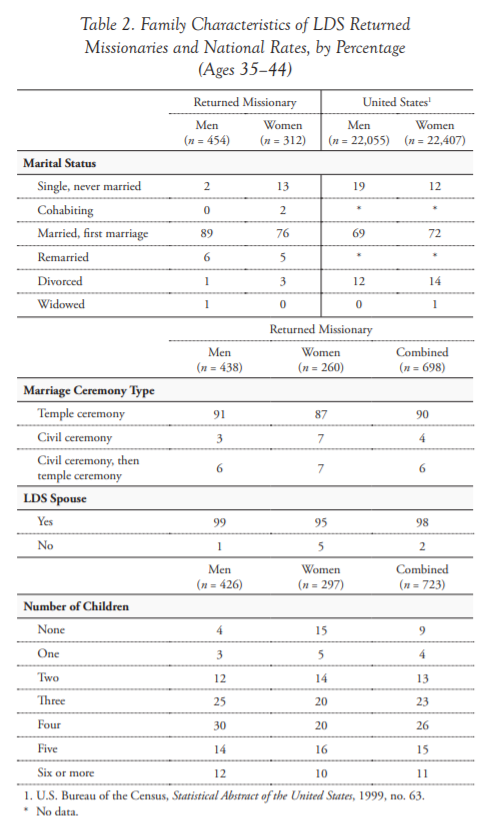

Family life. The LDS Church is known for its strong family values. Accordingly, we looked at a number of family indicators to ascertain the family life of returned missionaries. Table 2 shows the marital status of returned missionaries. Among the male 17-year group, about 90% were in their first marriage, while 6% had been divorced or remarried. Only 1% were currently divorced, and 2% were still single.

Among men in the national sample in 1998, around 69% were married (first marriage or remarried), 12% were divorced, and almost 19% had never married (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1999, no. 63). Thus, returned-missionary men were more likely to get married and less likely to divorce than other men across the United States.

Among women returned missionaries, 75% of those in the 17-year group were married (first marriage), 5% were remarried, about 4% were separated or divorced, and 13% had never married. For women of comparable age on a national scale (1998), about 72% were married (first marriage or remarried), around 14% were divorced, and 12% had never married (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1999, no. 63). Like the men, these figures show that the divorce rate among returned-missionary women is much lower than the national rate. The percentage who had not yet married was nearly identical.

We also found that nearly all returned missionaries who were married had a spouse who is a member of the Church, and 96% either had married in the temple or had been sealed later. In addition, a relatively high fertility rate was discovered. Latter-day Saints have been known for having larger families than the national average, and this study verifies this pattern. The average number of children among returned-missionary families for the 17-year group was 3.7 for the men and 3.2 for the women. In contrast, the average number of children ever born to women between the ages of 35 and 44 in the United States in 1995 was around 1.9 (Chadwick & Heaton, 1999).

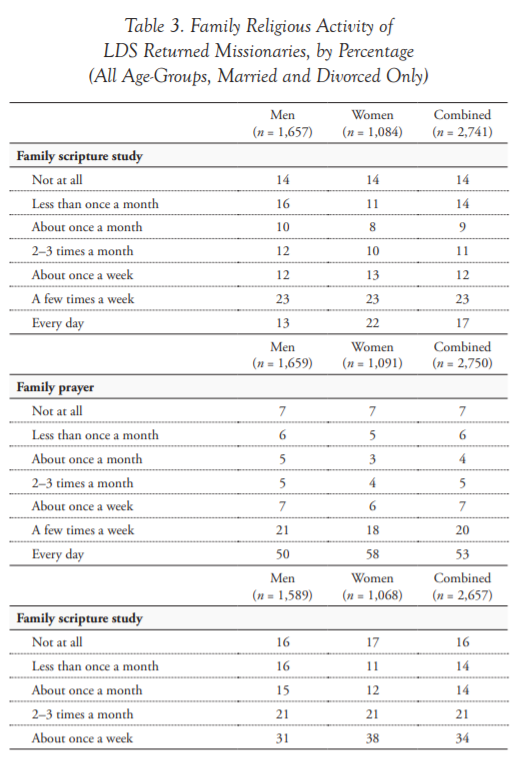

Religious activity. Full-time missionary service provides young adults with an opportunity unlike any other to develop personal spiritual habits. Results from our research suggest that these habits are not abandoned once the missionaries return home. For example, 87% of all returned missionaries attend sacrament meeting almost every week (see Tables 3 and 4). Sunday School and priesthood/

A comparison between men and women reveals women are consistently higher in their religiosity than men. This fits the same pattern found nationally, as women are often much higher in their religious beliefs, commitments, and behavior than men (Stark, 2004).

The relatively high rates of religiosity for returned missionaries is notable. This is especially significant given that our sample included not only recently returned missionaries but also those who have been home for a considerable length of time. These findings, when added to results from previous research on returned missionaries, provides consistently strong evidence that the vast majority of returned missionaries stay strongly committed to gospel values not only immediately upon their return but also later in their lives.

Family religious activities are at the core of a Latter-day Saint home. Recently, Elder Russell M. Nelson (1999) counseled, “Happiness at home is most likely to be achieved when practices there are founded upon the teachings of Jesus Christ. Ours is the responsibility to ensure that we have family prayer, scripture study, and family home evening” (p. 38). We assessed these three religious activities among returned-missionary families. As Table 4 illustrates, we found that 73% have family prayer at least a few times a week, 39% hold family scripture study that often, and 55% hold family home evening at least two or three times a month. Given the complexities and demands on the modern family, these figures indicate a relatively sound commitment to family religious practices in the homes of returned missionaries.

Comparing Recently Returned Missionaries to Those of a Generation Ago

Research on secularization of Latter-day Saints shows they may show resistance to the acceptance of “worldly values.” Stark (1984; 1996) found little evidence to support the idea that the LDS Church was in any kind of religious decline. He explained that the “secularization thesis would hold that religious movements such as Mormonism will do best in places where modernization has had the least impact. . . . These assumptions about secularization are refuted by research. . . . Mormons thrive in the most, not the least, secularized nations” (1984, p. 25).

In 1984, Albrecht and Heaton found that among many religious groups in the United States: “Educational achievement impacts negatively on religious commitment and that increased levels of education often lead to apostasy as individuals encounter views that de-emphasize spiritual growth and elevate scientific and intellectual achievement.” (1998, p. 25).

For Latter-day Saints, however, they found a positive relationship between education and religiosity and concluded that there was very little evidence to support the secularization thesis. Chapter 4 in this book provides powerful evidence refuting the notion that education is resulting in the secularization of LDS young adults. Others have found similar results (Stott, 1984; Merrill, Lyon, & Jensen, 2003; Top & Chadwick, 2001).

To test the secularization notion among returned missionaries, we examined the religiosity between returned missionaries of the 1960s and 1970s to those of the 1980s and 1990s. In 1977, Madsen conducted a survey of nearly 1800 returned missionaries from the United States who had been home from their missions up to 10 years. This information provided a baseline against which we compared our sample in both private and public religiosity as well as marital status. Private religious behavior includes such things as personal scripture study, personal prayer, holding a current temple recommend, and paying tithing. Areas of public religious behavior include attendance at sacrament meeting and other church meetings.

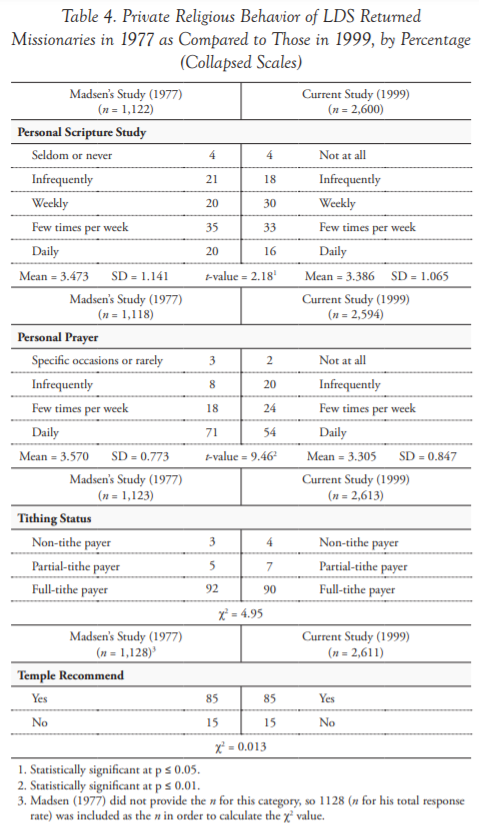

Private religious behavior. We found that returned missionaries in our sample read their scriptures and prayed somewhat less than those in Madsen’s study. As illustrated in Table 5, 49% of current returned missionaries had personal scripture study at least a few times a week or daily, compared to 55% of those 30 years earlier. In addition, 54% had daily prayer, compared to Madsen’s sample, which was at around 71%. About 85% in each group held a current temple recommend, and both groups were between 90 and 92% as full-tithe payers.

Why returned missionaries are praying and reading their scriptures less today than they did 30 years ago is not clear. Certainly secularization could account for this decline. Modernization has set up a more competitive world, requiring greater time demands on the family. More fathers are working longer, more mothers are entering the workplace, and more children are competing and specializing at school than they were 30 years ago. For returned missionaries, as with the rest of society, this tide of busyness may be sweeping them up, perhaps leaving them less time for private religious observances.

Another possibility is that given the added emphasis the Church has placed on the family during the past several decades, private religious practices are shifting to family religious practices. In other words, married couples, although recognizing the value of private religiosity, may end up substituting family prayer and scripture study for personal prayer and scripture study in order to keep up with the demands of other responsibilities.

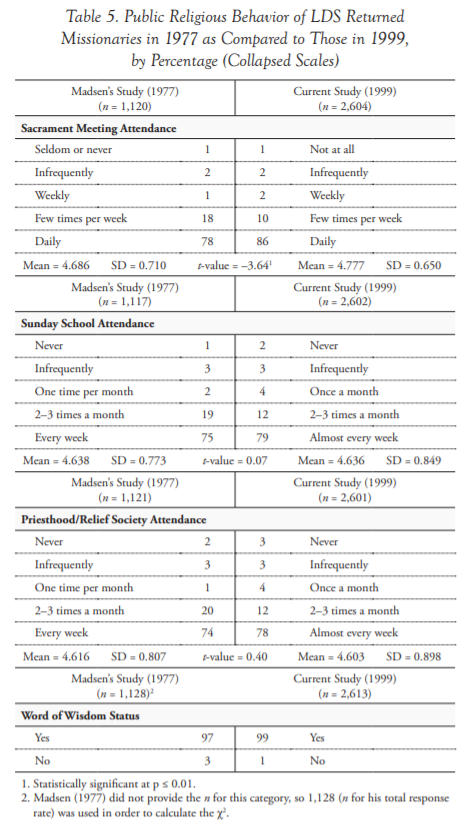

Public religious behavior. As for public religiosity, 86% of the returned missionaries we studied attended sacrament meeting on a weekly basis. This is higher than the 78% reported by returned missionaries 30 years ago. Both groups of returned missionaries ranged between 75 and 79% weekly attendance at Sunday School and priesthood/

Even though sacrament meeting attendance is significantly higher now than it was 30 years ago, a second look at where the shift occurs (see Table 5) explains that most of the movement is between those who attended “two to three times a month” and “almost every week.” In other words, the difference is found among those who were already very active and then became even more active.

The increase of public religiosity during the past 30 years can certainly be attributed to an increase in personal faith. There may be, however, a couple of structural explanations as well. One is that the Church has continued to build buildings closer to the people, making it easier to attend Church than in the past. A second possibility is because of the establishment in the early 1980s of the three-hour block of Church meetings. Prior to that time, members attended Sunday morning meetings comprised of priesthood and Sunday School, and later in the evening they would return for sacrament meeting. Unlike returned missionaries of the 1960s and 1970s, the establishment of the more time- and travel-efficient three-hour meetings may have played a part in higher Church attendance among returned missionaries of the 1980s and 1990s. Whatever the reasons, in the end, returned missionaries continue to remain extremely active in the public aspects of their religiosity in spite of so-called secularization.

When looking at the overall trend in religiosity among returned missionaries during the past several decades, we can see that some measures in the private realm have declined, while others have held steady. In the public sector, some indicators have increased, and others have remained the same. It would be premature, then, to suggest that secularization is found among returned missionaries. Other than private prayer, it is our feeling that as a whole, the religious behavior of returned missionaries today is generally similar to those studied in 1977.

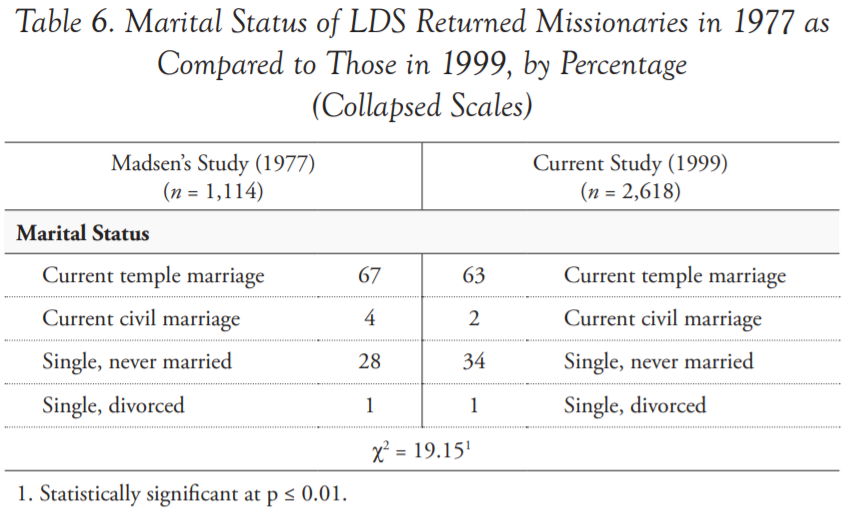

Marital status and temple marriage. Another indicator of religious conviction among Latter-day Saints is temple marriage. We found that 63% of those in our sample had a current temple marriage, as compared to 67% of Madsen’s sample (see Table 6). This marks a decrease of 4 percentage points over a 30-year period. However, the number of those remaining single has increased by 6 percentage points from 28% in Madsen’s sample to 34% in our sample.

It appears that the decrease in temple marriages is attributed to the higher numbers of those not yet married, rather than an increase in civil marriages. This tendency for returned missionaries to wait longer to marry follows the pattern in the United States over the same period of time. In the 1970s men and women in the United States married around the age of 24 and 21, respectively. The average age in 1990 was 26 for men and 24 for women. Increased opportunities for both education and work are some of the reasons attributed to the postponement of marriage among Americans (Gelles, 1995).

Helping Returned Missionaries Stay Committed to Gospel Values

As mentioned earlier, Church leaders have encouraged returned missionaries to continue living the same standards after their missions as they did while serving. Elder Dallin H. Oaks (1997) said: “I say to our returned missionaries—men and women who have made covenants to serve the Lord and who have already served Him in the great work proclaiming the gospel and perfecting the Saints—are you being true to the faith? Do you have the faith and continuing commitment to demonstrate the principles of the gospel in your own lives, consistently? You have served well, but do you, like the pioneers, have the courage and the consistency to be true to the faith and to endure to the end?” (p. 73).

We found that the large majority of returned missionaries in our study were doing well in their early postmission adjustments. For example, when asked how difficult it was for them to adjust to postmission life, only about 20% indicated that it was either “quite difficult” or “very difficult.” The vast majority (80%) indicated that this adjustment was either “somewhat difficult,” “a little difficult,” or “not at all difficult.”

We further examined adjustment issues by asking returned missionaries to responded to three open-ended questions about the specific difficulties they encountered as they returned home, and what things the returned missionaries themselves, as well as family and Church leaders, could do to help ease the stress of this transition.

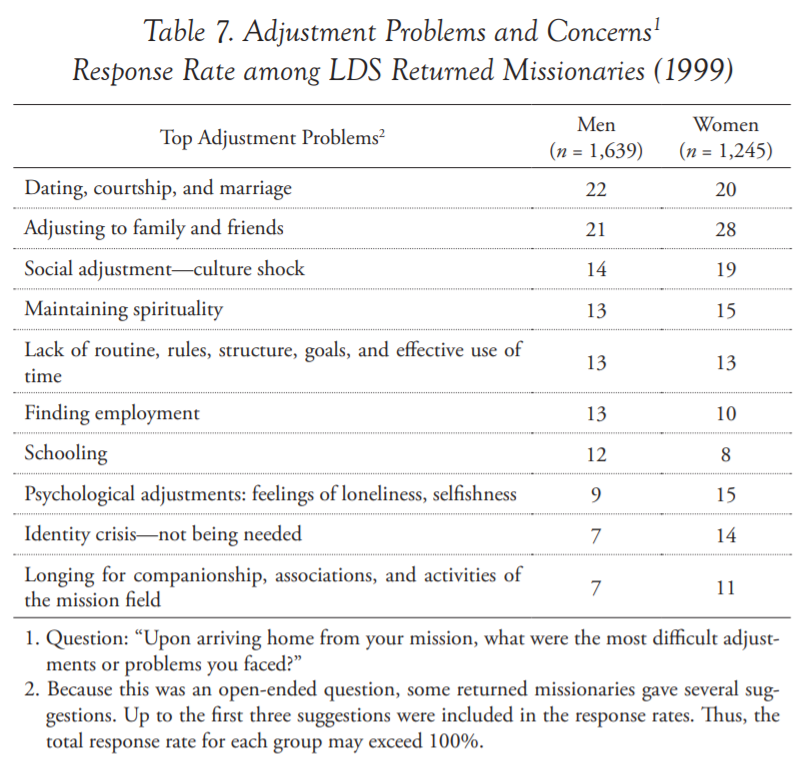

Adjustment concerns. The major concerns among returned- missionary men are how to handle dating and the marriage question, adjusting to family and friends, and dealing with culture shock (see Table 7). One man wrote, “Dating was a challenge, as relationships with young women had been carefully monitored by myself for two years. Also, dating leads to marriage, and with my parents’ marriage ending in divorce, this activity was scary.”

Another man reported the most difficult adjustment he faced was how “to make so many critical decisions about my schooling, career, employment, and social adjustment in such a short time.”

Women rated adjusting to family and friends and culture shock as the top two problems they faced. One young woman explained that because she saw her family in a new light, “[I] was very critical of them. This caused big problems with [my] mother.”

Other women found that old friends had changed. “My friends were all married,” one woman wrote, “so the friends I had were all in the mission field. I was very lonely.”

Another commented, “All of my closest friends were either married or currently serving a mission, so I felt the adjustment of making new friends. Also, I had a boyfriend who had waited for me, and we went through an adjustment phase and the stresses of deciding whether to get married, etc.” As this statement suggests, a concern about dating, courtship, and marriage was also ranked as a difficult problem for women. Although this “social life” adjustment does not appear to be as critical for the women as it is for the men, it is still a major concern for returned-missionary women.

Women ranked psychological adjustments higher on the list than men did. One woman explained that the most difficult adjustment she faced was, “Having a focus on myself! I felt so guilty. . . . Finding a new social group seemed so daunting and impossible. I felt so ‘nerdish’ and that was a new feeling and made me feel guilty that I cared about all that.” It appears that some young women may be more prone to experience a sense of guilt or frustration than men do as they make the transition from the mission field to home.

Although our focus here is on returned missionaries, it should be pointed out that these types of feelings and adjustments are certainly not unique to returned missionaries. All LDS young adults experience similar challenges, and they must navigate their way through what is termed “the transition into adulthood.”

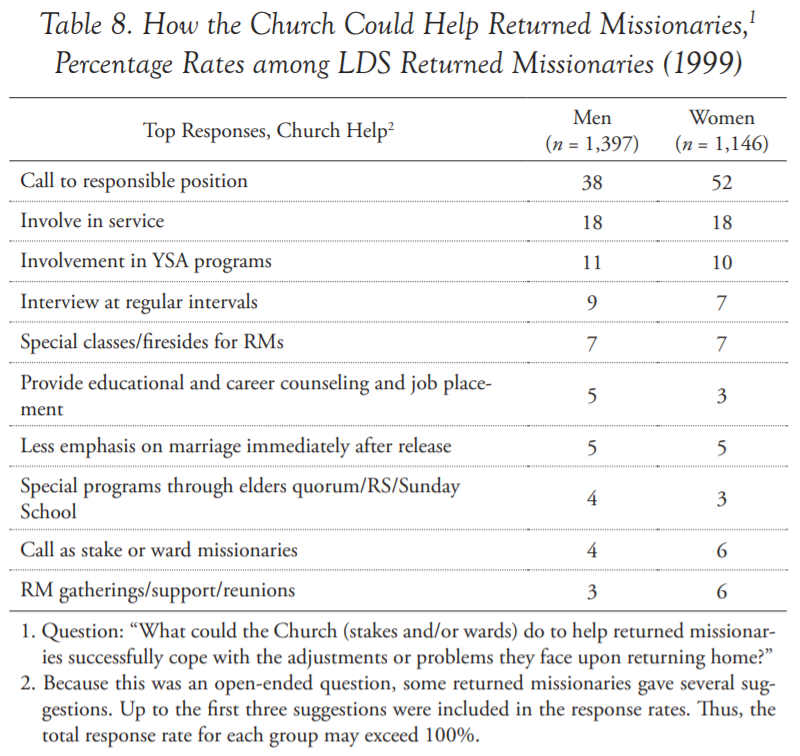

How the Church could help. When asked how the Church could help returned missionaries successfully cope with adjustments upon their return home, the most frequent suggestion was for them to receive a call to a responsible position as soon as possible (see Table 8). This is important in light of the statement by President Hinckley mentioned earlier that if every returning missionary had a “meaningful responsibility” once they returned home, they would have a greater chance at remaining strong and active in the Church. Confirming President Hinckley’s invitation, one young man stated, “Put the RMs to work right away, meaning a calling. Don’t let them drift for weeks or months with no responsibility. Challenge them. Most missionaries enjoyed the challenge of knocking on stranger’s doors, etc. Don’t feel like they need ‘time off.’”

This sentiment was also expressed among the women in the study. For example, one woman declared, “I think that missionaries need to be involved immediately in Church positions so they stay active in serving and teaching.” She concluded, “They need to feel that their experiences and service to the Lord are valued and appreciated. The best way to do that is use them.”

Another women advised, “Give them a calling, or keep them busy. Be their friend. Talk with them on an individual basis. Really care about them.”

Other insightful suggestions from both men and women included involvement in service, providing strong young single adult programs, holding interviews at regular intervals with a Church leader, and holding special classes or seminars for returned missionaries. Counsel, support, and encouragement from Church leaders concerning educational pursuits, the launching of careers, and dating would perhaps ease the difficult decisions following mission service.

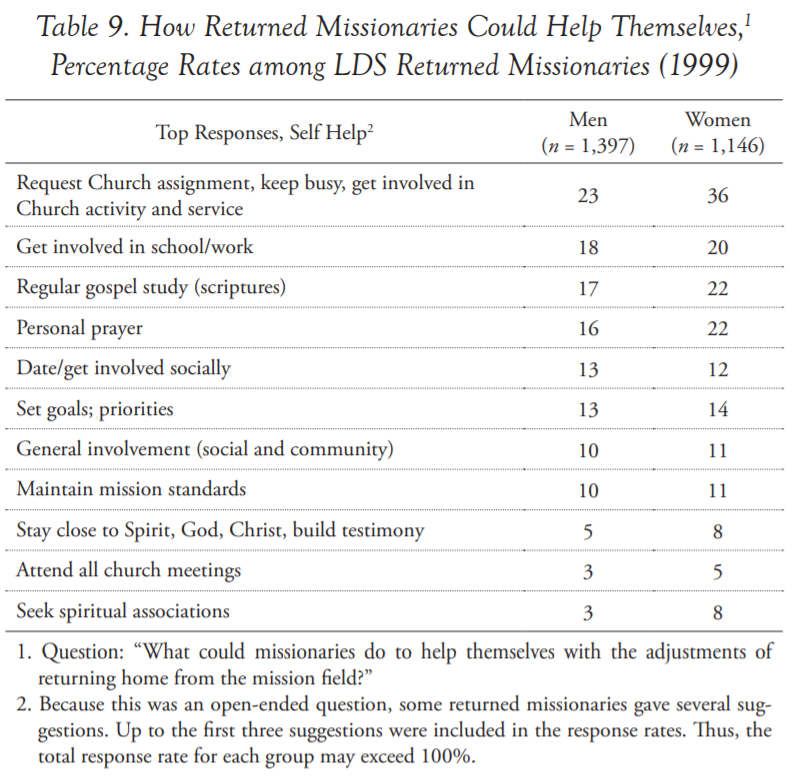

How returned missionaries could help themselves. The most frequent suggestion on how returned missionaries could help themselves was for them to request a church assignment, keep busy, and get involved in church activity and service (see Table 9). In other words, newly returned missionaries should be proactive in finding ways to serve. Setting goals, getting involved in school and work, having a regular gospel study program, and continuing to hold personal prayer were also important activities suggested by returned missionaries.

One young man said, “Continue to keep mission grooming standards and scripture study and prayer schedules. Don’t ‘take a break’ from serving in the Church (go on splits, home teach, attend firesides and socials, etc.).” Other suggestions were getting involved in dating, maintaining mission standards, seeking spiritual associations, attending all church meetings, and accepting personal responsibility for adjustment.

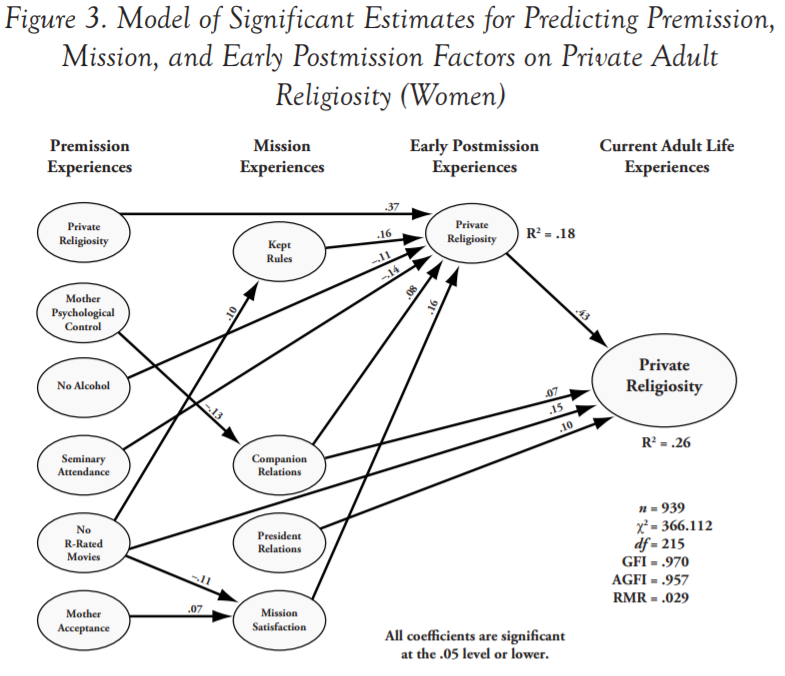

Staying committed to private religiosity in adulthood. Another way in which we probed the dynamics of the postmission experience was by assessing what factors in returned missionaries’ high school and mission years are related to helping them stay strong in their private religiosity after they return home. In other words, we wanted to know what things a person can do before, during, and soon after a mission that will help them to maintain a strong commitment to reading scriptures, praying, and thinking about religion.

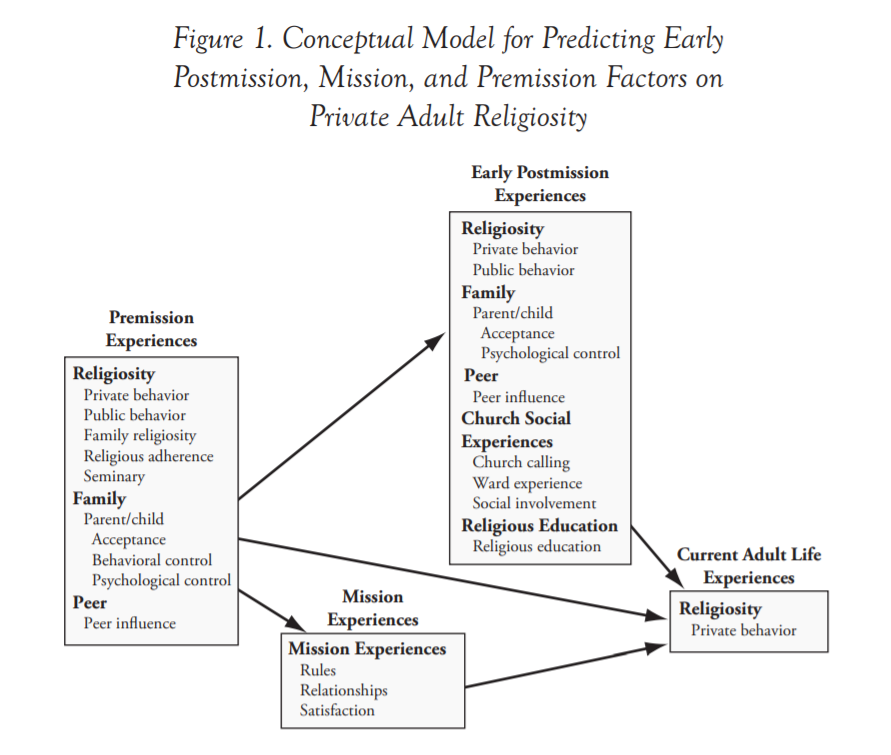

Figure 1 shows a conceptual model of the various dimensions that we hypothesized would influence private religiosity in adulthood. Private, public, and family religious practices at various times in life, parent and peer influences during adolescence, mission experiences, religious education, and church social involvement after a mission were all included in the model.

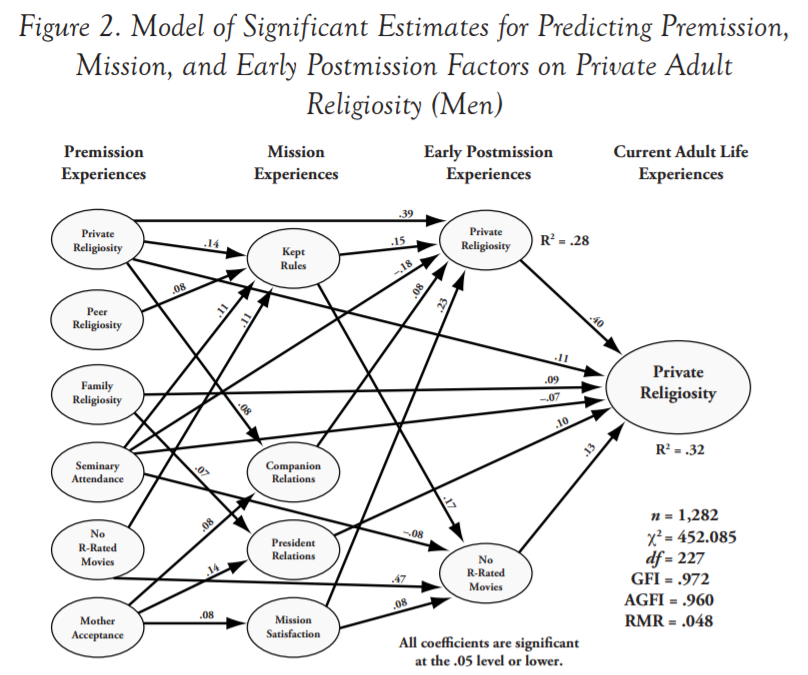

Results from our assessment concluded that private religiosity when the future missionaries were young was by far the most powerful predictor of private religiosity in adulthood. For example, the strongest correlation in the model was between early postmission private religiosity and adult private religiosity for both the men and the women. The relationship between premission private religiosity and early postmission private religiosity was also significant. Thus, if returned missionaries had a strong commitment to reading scriptures, praying, and thinking about religion during their high school years, they were more likely to continue these practices during the first year home from a mission, which leads to higher commitment later in life.

Another essential factor that led to strong private religiosity in adulthood, at least for the men, was the avoidance of R-rated movies and videos after their missions. We used R-rated media as an indicator of exposure to things such as profanity, violence, and pornography in the media. A strong relationship between avoiding R-rated movies and videos before a mission and staying away from them immediately after was also found. In other words, if youth disciplined themselves not to see R-rated movies (and for that matter, any media, regardless of rating, that offers exposure to inappropriate behavior) while in their high school years, they were less likely to view this material during the first year home from their missions, as well as later.

Private religiosity in adulthood was influenced by the type of mission experience as well, albeit indirectly. Findings vary between men and women. However, in general, missionaries who kept the mission rules, got along well with their companions, and had a satisfying mission experience were more likely to continue to read their scriptures, pray, and think about religion right after their missions, which is strongly linked to private religiosity in adulthood. In addition, men who kept mission rules and were more satisfied with their missions were more likely to avoid R-rated media immediately after their missions, thus leading them to higher religiosity in later life.

So the mission experience seems to matter when it comes to religious commitment later in life. However, we are a little more cautious when it comes to interpreting these correlations, because we are unsure if they represent a causal relationship or are the outcome of selection bias. In other words, certain missionaries bring with them into the mission field traits that help them keep mission rules or get along with a companion. Thus, the indicators we used to measure the mission experience may actually be measuring premission characteristics.

In addition, we found that family experiences, including family religious practices and the parent-child relationship, had a significant influence on private religiosity in adulthood. Specifically, men who were raised in homes where family home evening, family prayer, and family scripture study were practiced had higher adult private religiosity.

Notably, this direct relationship was not found for the women. They seemed to be more resilient to any neutral or negative experiences in their families than the men in terms of premission family religious practices. Perhaps the influence of Church advisors and/

We also found that the parent-child relationship during high school is indirectly related to adult private religiosity through the mission experiences. For both men and women, their mother’s acceptance influenced their experiences in the mission field. Women, however, were also influenced by their mother’s psychological control, directly influencing how these women got along with their mission companions.

Conclusion

Many feel that the postmission experience is a pivotal time for LDS young adults, where maintaining the religious identity they developed in the mission field is tested. Latter-day Saints tend to attach higher spiritual and social expectations to returned missionaries given their unique “life-transforming” experiences in the mission field. Results from this study indicate that such high expectations may be warranted. Returned missionaries are doing very well not only in the religious aspects of their lives but in a number of other areas as well.

Of significance is the finding that the socioeconomic status among returned missionaries exceeds that of the national average. Family characteristics were also different than those nationally, with returned missionaries showing a much lower average of divorce and also more children than their peers across the United States.

High religiosity across a number of indicators was also found among returned missionaries. Although it is unfortunate that any returned missionary falls into inactivity, the fact that almost nine out of ten returned missionaries continue to regularly attend church for up to 17 years after their missions is remarkable. A comparison of returned missionaries’ private religiosity over the past 30 years show a modest decline in their scripture study and prayer, yet these levels still remain relatively high. On the other hand, an increase in church attendance was also found. A number of other factors remained the same. All of this underscores the point that the vast majority of returned missionaries continue to hold strong to their religious convictions and refutes any notion that there is an emerging pattern of inactivity or secularization among them.

The study shows that if returned missionaries had a strong commitment to private religiosity during their high school years, they were more likely to continue that practice during the first year home from their missions, which in turn continued into adulthood. Thus, it is important for parents and Church leaders to help young men and young women to begin a habit of personal prayer and scripture study during these impressionable high school years.

Other notable factors that were associated with private religiosity in adulthood were the avoidance of viewing R-rated movies, having positive mission experiences and attitudes, being involved in family home evening, family prayer, family scripture study while a youth, and having a positive relationship with parents.

Finally, the majority of returned missionaries are adjusting to regular life after a mission very well. As suggested by the returned missionaries themselves, the most important thing they can do to help themselves during this stage is to continue to maintain good spiritual habits, such as daily prayer and scripture study, church attendance, and serving in significant callings in their wards. Many of them recognize that such spiritual maintenance will help them have the spiritual resources to draw upon when they are challenged by other areas in their life, including dating, family, culture shock, school, and work.

In 1997, President Hinckley counseled Church leaders that the most important things they can do to help retain new converts is to provide them with “a friend, a responsibility, and nurturing with ‘the good word of God’” (Hinckley, 1997). Certainly this counsel can pertain to all members of the Church, and based on the findings in this study, it can especially be applied to “retaining” newly returned missionaries. Once home, if returned missionaries are provided with the responsibility of a church calling, involve themselves in church social activities where they can develop good friendships, and continue to be nurtured through personal prayer and scripture study, they will find the strength to successfully navigate their way through their postmission pursuits and continue to contribute as members of their family, society, and the Church.

References

Albrecht, S. L., & Heaton, T. (1984). Secularization, higher education, and religiosity. Review of Religious Research, 26, 43–58.

Caplow, T., Bahr, H. M., & Chadwick, B. A. (1983). All faithful people: Change and continuity in Middletown’s religion. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Chadwick, B. A., & Heaton, T. B. (1999). Statistical handbook on the American family. Phoenix: Oryx Press.

Clawson, R. (1936). The returned missionary. Improvement Era, 39, 590–594.

Duke, J. T., & Johnson, B. L. (1998). The religiosity of Mormon men and women through the life cycle. In J. T. Duke (Ed.), Latter-day Saint social life: Social research on the LDS Church and its members. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 315–343.

Gelles, R. J. (1995). Contemporary Families. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Groberg, L. B. (1936). A preliminary study of certain activities, the religious attitudes, and financial status of seventy-four returned missionaries residing within Wayne Stake, Wayne County, Utah (Master’s thesis). Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Hinckley, G. B. (2001). Latter-day counsel: selections from addresses by President Gordon B. Hinckley. Ensign, 31(3), 64.

Hinckley, G. B. (2001). A prophet’s counsel and prayer for youth. Ensign, 27(1), 2–11.

Hinckley, G. B. (1997). Converts and young men. Ensign, 27(5), 47–50.

Hoglund, W. J. (1971). A comparative study of the relative levels of physical fitness of male LDS missionaries who are commencing and those just concluding their missionary service (Master’s thesis). Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

King, A. W. (1936). A survey of the religious, social, and economic activities and practices of returned missionaries (Master’s thesis). Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Lechner, F. J. (1991). The case against secularization: A rebuttal. Social Forces, 69, 1103–1119.

Madsen, J. M. (1977). Church activity of LDS returned missionaries (Doctoral dissertation). Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

McClendon, R. J. (2000). The LDS returned missionary: Religious activity and post mission adjustment (Doctoral dissertation). Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Merrill, R. M., Lyan, J. L., & Jensen, W. J. (2003). Lack of secularizating influence of education on religious activity and parity among Mormons. Journal of the Scientific Study of Religion, 42 (1), 113–124.

Nelson, R. M. (1999). Our sacred duty to honor women. Ensign, 29(5), 38.

Oaks, D. H. (1997). Following the Pioneers. Ensign, 27(11), 72–74.

Probst, R. G. (1936). A study of fifty-seven return missionaries of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Idaho Stake of Bannock County, Idaho (Master’s thesis). Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Roghaar, H. B. (1991). The influence of primary social institutions and adolescent religiosity on young adult male religious observance (Doctoral dissertation). Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

Stark, R. (2004). Sociology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Stark, R. (1996). Postscript: So far, so good. Review of Religious Research, 38, 175–178.

Stark, R., & Iannaccone, L. (1992). Sociology of religion. In Borgatta, E. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Sociology, 2029–2037. New York: Macmillan.

Stark, R. (1984). The rise of a new world faith. Review of Religious Research, 26, 18–27.

Stott, G. (1984). Effects of college education on the religious involvement of Latter-day Saints. BYU Studies, 24, 43–52.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (1995). The family: A proclamation to the world. Ensign, 25(11), 102.

Thomas, D. L. (1992). Reflections on adolescent and young adult development: Religious, familial, and educational identities. Family Perspective, 26, 383–404.

Top, B. L., & Chadwick, B.A. (2001). “Seek learning, even by study and also by faith”: The relationship between personal religiosity and academic achievement among Latter-day Saint high school students. Religious Educator, 2(2), 121–137.

U.S. Bureau of the Census (2000), Statistical abstract of the United States, 2000 (120th Edition), Washington DC.

U.S. Bureau of the Census (1999), Statistical abstract of the United States, 1999 (119th Edition). Washington DC.

Warner, S. R. (1993). Work in progress toward a new paradigm for the sociological study of religion in the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 98, 1044–1093.

Yamane, D. (1997). Secularization on trial: In defense of neosecularization paradigm. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 36, 109–122.