Discipleship: Brigham Young and Joseph Smith

Ronald K. Esplin

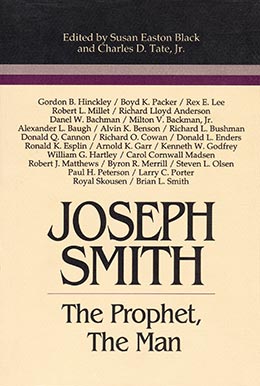

Ronald K. Esplin, “Discipleship: Brigham Young and Joseph Smith,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet, The Man, ed. Susan Easton Black and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1993), 241–69.

Ronald K. Esplin was director of the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Church History at Brigham Young University when this was published.

Brigham Young announced, “I feel like shouting hallelujah, all the time, when I think that I ever know Joseph Smith, the Prophet whom the Lord raised up… and to whom He gave keys and power to build up the kingdom of God on the earth and sustain it” (Journal of Discourses 3:51; hereafter JD). Today many look back on Brigham Young as the Great Leader, a man singularly capable of molding a people and building a flourishing commonwealth in an unpromising desert, but that is not how he thought of himself. Even after leading the Saints for 30 years, in his own eyes he was the Disciple, a follower of his prophet and mentor Joseph Smith. He understood and acknowledged that in ways large and small his leadership flowed from that discipleship.

“I know how I received the knowledge that I have got,” he said in 1866. During the early years with Joseph, “I had but one prayer, and I offered it all the time, and that was that I might be permitted to hear Joseph speak on doctrine, and see his mind reach out untrammeled to grasp the deep things of God.” He maintained that “an angel never watched him closer” and that he “would constantly watch him if possible and learn doctrine and principle beyond that which he expressed.” It required several years of this close attention to the Prophet, Brigham declared with some exaggeration, “before I pretended to open my mouth to speak at all” (Brigham Young Papers, Discourse, 8 Oct 1866). He took care never to let “an opportunity pass of getting with the Prophet Joseph and of hearing him speak in public or in private, so that I might draw understanding from the fountain from which he spoke.” “This,” he insisted, “is the secret of the success of your humble servant” (JD 12:269-70).

Brigham Young was the quintessential disciple. He loved Joseph as a friend and admired and emulated his personal qualities, but more importantly, he also revered and followed him as a prophet of God and an apostle of Jesus Christ. Though he gained a testimony and was baptized months before meeting the Prophet, for Brigham Young the restoration and the accompanying opportunities that changed his life came through Joseph Smith. And, once he met him, he devoted his life to supporting, defending, and learning from “our Moses that the Lord has given us” (Brigham Young Letter to Mary Ann Young, 16 Oct 1840, LDS Church Archives; hereafter CA). Joseph was his father in the gospel, his mentor, his model, his friend; he was Joseph’s intrepid defender, enthusiastic supporter, and finally successor, who unwaveringly and forever sought to carry out the Prophet’s measures.

Living in western New York, a youthful Brigham Young experienced the same religious upheavals that buffeted Joseph Smith, and they left him just as unsatisfied. “I saw them get religion all around me—men were rolling and holloring and bawling and thumping but it had no effect on me,” he later recalled. “I wanted to know the truth that I might not be fooled—children and young men got religion, but I could not” (Brigham Young Papers, Minutes, 8 Jan 1845). Local ministers provided moral teaching, but none answered his questions about God or told him what he must do to be saved. He longed to associate not with a preacher of morals alone but with a prophet who possessed the knowledge and power of heaven, and he concluded that he would gladly give all the riches he ever could obtain to meet one who could show him about God, heaven, and the plan of salvation (JD 9:248). Later he remembered having felt “that if I could see the face of a prophet, such as had lived on the earth in former times, a man that had revelations, to whom the heavens were opened, who knew God and his character, I would freely circumscribe the earth on my hands and knees” (JD 4:104).

Not surprisingly, given this deep desire and the years those yearnings went unsatisfied, when Brigham Young finally became convinced of the reality of the Restoration and that Joseph Smith was such a prophet, these truths transformed his life. But not immediately. His native caution and fear of being deceived prevented him from embracing these truths when first he encountered them.

At age 29, living then only a half-day’s walk from Joseph Smith’s Palmyra, Brigham Young first saw the Book of Mormon. Although intrigued, even hopeful, he nonetheless would not allow himself to believe too readily. Despite his long search, he was unwilling to make a mistake about something so profoundly important to life and salvation. Perhaps that is why he didn’t journey immediately to meet the young Prophet. He sought the advice of family and friends, several of whom then became Latter-day Saints before he did. He tested his own heart and soul: If this is true, would it be to him more important than life itself? Could he, as the New Testament demanded, forsake all, even family, for the true gospel of Christ?

One by one he wrestled with his questions and doubts until each was resolved, but still he hesitated. After trying to judge the Restoration largely with his own abilities, the plain testimony of a simple elder, a man without eloquence who could say only “I know,” finally brought Brigham Young into the Church. “The Holy Ghost proceeding from that individual illuminated my understanding, and light, glory, and immortality were before me. I was encircled by them, filled by them, and I knew for myself that the testimony of the man was true.” This testimony “like fire in my bones” swept away his doubts and planted his feet in a new direction (JD 1:90). Thereafter he could say that when first he encountered the Restoration, “I fathomed it as far as I could and then embraced it for all the day long” (Brigham Young Papers, Minutes, 8 Jan 1845).

From that day forward, Brigham Young knew that Joseph Smith was a prophet of God, a man such as he had searched for in his youth—a conviction he carried to his grave. Though he had yet to meet Joseph, who had moved from New York, and would not for more than half a year after his April 1832 baptism, the remarkable transformation in Brigham Young’s life had begun, a process that Joseph would later guide and speed as mentor, friend and model. And the impact of Joseph would be the more profound because it came after yearning and long searching for one who could teach him of God.

Brigham Young’s reputation at this time was that of a sober, honest, hard-working tradesman. He was noted for common sense, ingenuity and practicality, and not at all for impetuousness or displays of emotion. Indeed, if anything, he seemed gloomy and downcast. The man who later promoted dancing and theater as appropriate expressions of a joyful soul was nowhere in evidence, nor was the man who would close down his business the better to preach the glad tidings unencumbered. But that is what Brigham Young soon did.

Baptism by immersion suggests death followed by resurrection to new life. Seldom was the symbol more appropriate than in the case of Brigham Young. Hope and purpose replaced discouragement as if a curtain had been removed from the face of the sun. Instead of sorrow and grief, suddenly it became “Glory! Hallelujah! Praise God!” (JD 8:119; compare 3:320-21; 8:129). Indeed, he later insisted, from the day of his baptism forward, he felt as if he were in another world and that looking back into the old was “like looking into Hell” (Minutes, General, 7 Apr 1850).

From the time of his baptism Brigham felt an urge to preach. Although a man of humble background and unpolished speech who lacked the confidence to face an audience, the message of the Restoration gave him courage and the fire within refused him rest: “I wanted to thunder and roar out the Gospel to the nations. It burned in my bones like fire pent up. . . . Nothing would satisfy me but to cry abroad in the world, that the Lord was doing in the latter-days” (JD 1:313). Brigham’s initial preaching circuit was largely within his own region, especially while his wife Miriam, who was also baptized despite advanced consumption, still needed his care. After his wife’s death in September, a loss their new-found faith helped him bear, Vilate Kimball took charge of his two little girls, freeing him for a broader circuit. In the year following her death, he traveled twice to Canada and twice to Kirtland, Ohio, preaching along the way.

Though neighbors marveled at the dramatic changes when Brigham Young “got religion,” they could be aware of only part of the transformation underway in heart and soul. There began the process that eventually transformed Brigham, an uneducated “carpenter and joiner” of upstate New York, into “President Young,” a major religious leader and acclaimed pioneer colonizer of the Far West. After his conversion, Brigham Young’s new religion assumed first importance in his life. Preaching and teaching it became his first love, seeing its message spread and obeyed, his chief satisfaction, and attending to its needs, his principal concern. Pursing these interests brought new challenges and opportunities that harnessed his abilities and helped him develop new ones. In all of this Joseph Smith loomed large.

As a young man, Brigham had felt willing to cross the continent to talk with a man who could teach him of God. Naturally he was now anxious to visit Joseph Smith. In the fall of 1832, only three weeks after Miriam’s death, Brigham, his brother Joseph Young, and Heber Kimball set out for Kirtland. When they revealed the purpose of their trip to people along the way, some could not refrain from criticizing the Mormons, and one minister lectured them on Joseph Smith’s true character. Though he could not yet speak from personal acquaintance, this attack prompted Brigham to affirm his absolute faith in Joseph Smith and forcefully declare the basis of his own conviction. Even if the prophet he had never seen should prove to be a horse thief by day and a gambler by night, he maintained, “I know that the doctrine he preaches is the power of God to my salvation, if I live for it” (JD 8:15-16). The story of his November meeting with Joseph Smith, whom he encountered chopping wood near his home, is a familiar one. That is not where Brigham gained a testimony of Joseph as a prophet; he already had that. But it was his initial opportunity to learn first hand what a prophet might be like in the flesh, and he was not disappointed. He later testified that he did receive, there in the Ohio woods, a clear spiritual confirmation that Joseph Smith was what he claimed to be (Manuscript History 4).

Both Heber and Joseph Young later affirmed that on this occasion the Prophet Joseph, outside the hearing of Brigham made a remarkable prophecy to the effect that Brigham Young would one day preside over the Church (Esplin, “Emergence” 94-95). These reminiscent accounts are interesting not just because of the role Brigham Young came to play but because of the unusual quality of his discipleship. Though he was not alone in displaying unwavering devotion to the Prophet, it is possible that this comment or some other foreshadowing imparted to Brigham a sense of destiny and special responsibility that encouraged and focused him in his extraordinary devotion to learn all that he could at the feet of Joseph.

Brigham and his companions left Kirtland joyful at having met the Prophet and reinforced in their testimony of his authority and mission. They had found him to be all that a prophet should be, and that without stiff piety. Indeed, they found a prophet equally at home in the woods and fields as at the pulpit—or on his knees at home, where they joined him in prayer; a man who, though resolutely earnest about his God and his religious mission, nonetheless loved games, tests of strengths, parties, and music. In Joseph Smith, Brigham Young saw an untutored youth who yet had the confidence to face the world squarely, and he learned from Joseph that the Lord could rely on men just like himself—men of simple faith, courage and integrity—and bless them with all that was necessary to succeed. Joseph Smith’s example of a balanced and well-rounded man of God served as a key to unlock Brigham Young’s emotions and his confidence and abilities as a leader.

Brigham once described his parents as “some of the most strict religionists that lived upon the earth” (JD 6:290). Speaking about his youth, he said:

I was kept within very strict bounds, and was not allowed to walk more than half-an-hour on Sunday for exercise. The proper and necessary gambols of youth [were] denied me. . . . I had not a chance to dance when I was young, and never heard the enchanting tones of the violin, until I was eleven years of age; and then I thought I was on the high way to hell, if I suffered myself to linger and listen to it. (JD 2:94).

Fearful of being overpowered by emotions, which he therefore kept tightly in check, and trained since boyhood to avoid music, theater and other “frivolous” pursuits shunned by his Puritan forbearers, Brigham found in Joseph a man who enjoyed in moderation all good things and who knew how to keep such things in perspective. For Brigham Young this was liberating, and eventually it led to as profound a transformation in his emotional and cultural life as that which had already taken place in his spiritual life. Had Joseph not provided an appropriate counter to his stern, emotionally narrow upbringing, Brigham Young would have been quite a different man indeed.

The next spring Brigham Young returned to Kirtland for a brief visit, his second opportunity to “sit at the feet of Joseph.” As before, the Prophet’s impact on Brigham’s life was profound. Joseph had already announced “the Gathering,” urging members to congregate in the cities of Zion in order to build a new society and, at Kirtland, a temple to their God. Brigham knew of the teaching (those he accompanied from Canada were moving to Kirtland in response to it), but he had not applied it to himself. Driven since baptism by a fire in his bones, he had no intention of “gathering,” but instead expected to preach and baptize, pushing to Kirtland others who could assist in the building.

That was his view until he heard Joseph Smith address the elders in July 1833. Listening to the Prophet’s moving charge to dedicate themselves fully to building a new Zion on earth opened to Brigham a fuller vision of his responsibility. Though essential, preaching and baptizing were not enough; he now understood that he must help build, literally, the gathered communities of the Saints, including a House of the Lord. This clarion call to spend not another hour building up the kingdoms of this world furnished Brigham a life-long motto: “With us it is the kingdom of God, or nothing” on this earth (Brigham Young Papers, Minutes, 25 Dec 1857).

After baptism, the once despondent, earth-bound Brigham had soared to heaven, and Joseph Smith now brought him back. For Brigham Young, this began a process of welding temporal and spiritual into one whole, joining labors of muscle and hand with faith of heart and soul. “What is the nature and beauty of Joseph’s mission?” he later asked an audience: “When I saw Joseph Smith, he took heaven, figuratively speaking, and brought it down to earth; and he took the earth, brought it up, and opened up in plainness and simplicity, the things of God; and that is the beauty of his mission” (JD 5:332). As Brigham liked to say, Joseph took heaven and earth and made them shake hands.

Without delay Brigham Young returned to New York for his children and few belongings. There he found his friend Heber Kimball already convinced of the necessity of gathering. In Ohio that fall and winter Brigham married Mary Ann Angell, reestablished his household, and began applying his skills as a craftsman to building Kirtland. Here began a durable pattern: though he and other elders would continue to spend most summers preaching “abroad,” most winters would find them at home, tending to domestic concerns and building the communities of the Saints.

The first winter that Brigham Young spent in Joseph Smith’s Kirtland and the following spring of 1834, during which he spent night and day for three months with the Prophet as part of Zion’s Camp, cemented a relationship between Brigham and Joseph that thereafter could not be broken.

Zion’s Camp was especially pivotal. To every member of the ill-equipped band, the 900-mile foot journey to Missouri in the heat of summer was a great physical trial. To some it was a spiritual one, as well, for after great sacrifice Zion’s Camp was disbanded without restoring the Missouri Saints to their lands. But for Brigham Young, Heber Kimball, Wilford Woodruff, George A. Smith and others who had begun to share Joseph Smith’s vision of a sacred community, it proved a great blessing. While some chafed at Joseph’s leadership and complained when things went poorly, these men sensed the advantages of being led by a prophet of God as Moses anciently led the children of Israel, and they began to understand what Joseph was trying to accomplish.

“Joseph often addressed us in the name of the Lord while on our journey,” Wilford Woodruff later noted, “and often while addressing the camp he was clothed upon with much of the spirit of God” (1:9-10). Later retellings had a distinctly Old Testament flavor; they saw themselves as chosen servants blessed for faithfulness or chastised for disobedience. At times they witnessed God’s timely intervention in their behalf, giving prophetic warnings or preventing battle, but when they murmured or quarreled, they felt God’s wrath. To those who shared the Prophet’s vision, each experience confirmed anew the power and nearness of God and provided a way to understand the camp’s vicissitudes. According to the revelation that disbanded them, before Zion could be redeemed, the elders must be “taught more perfectly, and have experience, and know more perfectly concerning their duty, and the things which I require at their hands” (D&C 105:10). That explanation helped Brigham Young and others understand the problems of the camp without concluding that they had mistaken their God or had followed a false prophet. Indeed, it inspired renewed commitment as they contemplated a future “endowment of power from on high” which the revelation promised as a part of their preparation (D&C 105:11-13, 18, 37).

Zion’s Camp participants also viewed Joseph Smith at close range and observed his character. Joseph Young remembered how the Prophet led “not as a haughty chieftain, not as an arrogant man, but [as] a man filled with the Holy Ghost.” Oh “how kind and modest he was . . . but how determined and resolute in carrying out the will of the Lord” (“Reunion”). George A. Smith observed the same spirit. Though Joseph had both the care of the whole camp and “a full proport[io]n of blistered, bloody& sore feet,” he never complained, not even when others repeatedly grumbled to him of their miseries. When minor irritations nearly caused rebellion, George A. remembered that “Joseph had to bear with us and tutor us, like children” (George A. Smith “History”).

Brigham Young’s feelings were not ambivalent about Joseph or Zion’s Camp. Kirtland friends challenged him: What profit was there in calling men from their labors to Missouri and back? If the Lord commanded it, what object did He have in mind? Who has it benefitted? Brigham may not have had all the answers, but he know one who had benefitted: “I told those brethren that I was well paid—paid with heavy interest—yea that my measure was filled to overflowing with the knowledge that I had received by traveling with the Prophet” (JD 10:20).

Associating with Joseph Smith, learning from him, and experiencing important events with him, Brigham felt amply repaid. “I would not exchange the knowledge I have received this season for the whole of Geauga County” (JD 2:10).

I have travelled with Joseph a thousand miles. . . . I have watched him and observed every thing he said or did. . . . For the town of Kirtland I would not give the knowledge I got from Joseph on this Journey; and then you may take the State of Ohio and the United States. . . . It has done me good . . . and this was the starting point of my knowing how to lead Israel. (Salt Lake High Council Record)

Brigham went on Zion’s Camp not as a leader but as a follower. He set a good example, and he and his brother Joseph often buoyed up sagging spirits by singing the songs of Zion as they traveled, but only after the test of Zion’s Camp would significant leadership opportunities come. Indeed, even after his call as a member of the original Quorum of the Twelve Apostles a few months after his return to Ohio, he and his friend Heber Kimball were still viewed as the least of the young Church’s leaders. Some of the educated and polished “marveled” when they would meet Kimball or Young on the street their looks expressed “What a pity!” that the Lord could not find someone better to serve (JD 8:173). [1] But in one respect, they already excelled their peers: they were in Kirtland no stronger defenders of Joseph Smith, the Prophet of the Lord.

From the beginning in Kirtland there were detractors, and almost as early Brigham Young stood out as one who vigorously defended Joseph. Even his later statements about the period retain something of the emotional intensity of his defense: “When I saw a man stand in the path before the Prophet to dictate him, I felt like hurling him out of the way and branding him a fool,” he declared (JD 10:363-64). Essentially he did just that during an incident, included in his history, of catching a man loudly denouncing Joseph through the Kirtland streets after midnight. Cowhide in hand, Young jerked the man around and warned him that if he did not stop and let the people sleep, he would whip him on the spot. He declared that they had the Lord’s prophet right there and did not need the devil’s prophet yelling in the streets (Manuscript History 17). No doubt such characteristic vigor in defense of the Prophet was one reason Brigham Young became a prime target of Kirtland apostates in the months ahead.

After the dedication of the Kirtland Temple in the spring of 1836, the Prophet turned his attention to building Kirtland as the headquarters and temple city of the Saints, leading by 1837 to an increase in dissent and a division about the role of a prophet in “secular” affairs. Brigham Young and others who desired a sacred community led by “our Moses” had little sympathy with such detractors. Brigham, especially, challenged them to draw any meaningful line between the temporal and the spiritual, between where the Prophet could lead and where he must not.

At one point dissenters attempted to depose Joseph Smith while he was away and appoint David Whitmer in his stead. To determine how best to proceed, they held a council in the upper room of the temple. Most present were dissatisfied with Joseph, but Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball, the two senior members of the Twelve residing in Kirtland, and President John Smith, had learned of the plan and also attended. No doubt Brigham Young went “pretty well charged with plenty of powder and ball” until he felt “like a thousand lions,” as he described his emotions on another occasion (Brigham Young Papers, Discourse, 8 Oct 1866). After listening to the murmurings of rebellion against the Prophet, he rose up, and in a

plain and forcible manner, told them that Joseph was a Prophet, and I knew it, and that they might rail and slander him as much as they pleased; they could not destroy the appointment of the Prophet of God, they could only destroy their own authority, cut the thread that bound them to the Prophet and to God, and sink themselves to hell. (Manuscript History 16).

Young’s firm opposition enraged several, among them the “old pugilist” Jacob Bump. Physically restrained from attacking Brigham, Bump twisted and shouted, “How can I keep my hands off that man?” No less angered, Young retorted that Bump could lay them on if it gave him any relief. The meeting broke up with the dissenters unable to unite in opposition.

It should be noted that despite Brigham Young’s great confidence in Joseph Smith and his unwavering loyalty to the Prophet, he was not unaware that Joseph, like other mortals, had faults. “I admitted in my feelings and knew all the time that Joseph was a human being and subject to err,” he said later, “still it was none of my business to look after his faults.” When Brigham was tempted to question, he repented of his unbelief, “and that too, very suddenly.” Of course Joseph made mistakes, but “it was not for me to question whether Joseph was dictated by the Lord at all times and under all circumstances or not.” To avoid the trap that had ensnared others, Brigham refused to permit himself to dwell on Joseph’s supposed mistakes, nor could the testimony of others critical of Joseph sway him, “for he was superior to them all, and held the keys of salvation over them. Had I not thoroughly understood this and believed it, I much doubt whether I should ever have embraced what is called ‘Mormonism’” (JD 4:297-98).

Even amidst controversy, most members remained loyal to the Prophet and to his version of a new community under priesthood, but some leaders did not. Some of those closest to Joseph, including members of Brigham’s own quorum, found themselves at least briefly among the critics, and a number thereafter separated themselves permanently from the Church and its Prophet. Amidst this turmoil, Joseph Smith called Heber Kimball to head a mission—the first ever abroad—to England, a mission the Twelve would have jointly undertaken in happier circumstances. The thought of going alone to sophisticated Great Britain intimidated the uneducated Kimball and he pleaded that Brigham be allowed to accompany him. No, Joseph insisted: he would need Brigham at home (Kimball, President Heber C. Kimball’s Journal, 10-11).

As dissent raged, Brigham found himself literally in the forefront of defending his Prophet. While Sidney Rigdon and Hyrum Smith denounced apostates and buoyed up the faithful from the pulpit, Brigham Young, not yet comfortable in an intensely public role, labored unceasingly to defend Joseph in council and to win back dissenters one by one. And the crisis weighed heavily upon him. Reminiscing about it later, he confessed that in “those days” he went many a night without sleeping at all. “I prayed a good deal [and] my mind was constantly active in those days” (Woodruff 5:63). As Heber Kimball noted in his autobiography, emotion in Kirtland reached such a state that “a man’s life was in danger the moment he spoke in defense of the prophet of God,” and no one spoke out more vigorously than Brigham Young (Kimball “History of Heber C. Kimball”). Consequently, in the face of violence and threats, on 22 December 1837, Brigham Young fled Kirtland in order to save his life. He was the first to leave but not the last: less than three weeks later Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon also fled, and within a few months most of the faithful departed for Missouri.

The sad tale of Missouri need not concern us here. Rather than being in the center of things, Brigham Young first settled on a small farm a few miles from Far West where he attempted to nurse his wife back to health after the terrible ordeal of Kirtland. That proved providential, for when disaster overtook the Missouri Saints and many of the leaders, including all the presidency, were arrested, Brigham Young was relatively unknown, and, therefore, unmolested. That left him, along with Heber Kimball, who had just returned from England, free and able, assisted by a newly rejuvenated Quorum of the Twelve, to step forward and lead when Joseph could not. [2]

After directing the exodus from Missouri, Brigham Young faced critical decisions in Illinois, where most of the Saints had fled for safety. The first involved the question of a new home—or, even more basic, whether or not they needed a unique City of the Saints apart from others. Some, including important leaders, said no. Gathering, they insisted, always created opposition and they had had enough. Church members should simply live as others, getting together as Latter-day Saints on the Sabbath but otherwise fitting into existing communities so as to avoid difficulties. Brigham Young knew better. He reminded the Saints that Joseph had taught them of the importance of a sacred, separate community and of a temple. Scattered they could build neither (Esplin, “Emergence” 372-75). Following his lead, the people voted in March, 1838 to gather yet again. When the Prophet rejoined them a few weeks later, he ratified the decision and immediately confirmed arrangements to build a new city.

Meanwhile Brigham Young faced another decision: Should the Twelve return to Missouri, from which they had just fled (and which still imprisoned Joseph and Hyrum Smith, Parley P. Pratt of their own quorum, and others) in order to fulfill the revelation requiring them to gather 26 April on the Far West temple site before departing on their long-awaited mission to England (see D&C 118:4-5)? Several argued that surely under the circumstances the Lord would take the “will for the deed.” Brigham thought otherwise. He rebelled against letting their failure to return provide ammunition against Joseph and he had faith enough to go (Manuscript History 35). Enemies boasted that the revelation appointing a specific time and place “proved” that Joe Smith was not a true prophet, for it would not and could not be fulfilled.

Under Brigham Young’s leadership the apostles returned to Missouri and in the pre-dawn hours of 26 April gathered at the Far West temple site. They ordained two apostles, symbolically laid the temple cornerstone, sang hymns and prayed. Certain that the revelation could not be fulfilled, mob leaders had left no guard, and by the time they arrived later that morning, the apostles had come and gone. As they left Far West, Theodore Turley knocked on the door of apostate Isaac Russell who had taunted him for believing in a fallen prophet. Turley enjoyed leaving Russell astonished and speechless with the news that the Twelve had now fulfilled the revelation (History of the Church 3:336-40).

After the Missouri disaster, leaving destitute and seriously ill families in Illinois and traveling to England was a test of faith for Brigham and his fellow-apostles. It was also a test of discipleship. They left families in the hands of God and performed their duty brilliantly under the most difficult of circumstances because the Prophet Joseph had dispatched them on a mission that could not wait. Before their departure, Joseph counseled them to seek the Lord’s spirit, to be humble, and above all, to be united. Because Brigham Young and the other apostles devotedly followed his instructions, they became more untied as a quorum and therefore more powerful than ever before, and they experienced extraordinary success.

In England Brigham Young keenly felt the absence of Joseph’s counsel and of his companionship. In April 1840, only days after arriving, the apostles met to organize their work. Without delay Brigham mailed minutes of their proceedings to Joseph with a note that conveyed the void he felt at being so distant. Professing himself a servant, as willing to take counsel “as ever I was in my life,” Brigham implored Joseph to make known to them “the mind of the Lord, and his will concerning us,” especially if he saw “any thing in or about the whole affair, that is not right” (“Reports and Minutes” 1:119-22). Although Brigham yearned for counsel, communication was slow and the distance great, and he knew he must act on the best light he had. As he wrote the Prophet in September 1840: “Our motto is go ahead. Go ahead—& ahead we are determined to go—till we have conquered every foe. So come life or come death we’ll go ahead, but tell us if we are going wrong & we will right it” (Joseph Smith Papers, Brigham Young and Willard Richards letter to First Presidency, 5 Sep 1841).

After months with no letter from Joseph, one arrived in November 1840 which, though damaged and hard to decipher, seemed to express dissatisfaction with their handling of publications. Brigham Young revealed his feelings in a letter to his wife Mary Ann, noting that had they been able, they would have done some things differently, but “I have done all that I could to doe good and promote the cause we are in . . . the very best I could.” If there are problems, “I think Br. Joseph will tel us all about things when we return home,” but meanwhile “tell him to ennyrate to say what he wants me to doe and I will try to do it” (Brigham Young to Mary Ann Young, 12 Nov 1840, Blair Collection; with little formal education, Brigham Young and several of his associates necessarily spelled phonetically). When they finally received a lengthy December letter in early 1841, in which the Prophet expressed great confidence in the apostles and approval of all they had done, Brigham was overjoyed (Joseph Smith Papers, Letter to the Twelve, 15 Dec 1840).

Confident of his authority and that he was doing his best to serve the Lord, the long wait for direction from the Prophet did not hinder Brigham’s work, but the absence of his friend and mentor sill weighed upon him and he worried about Joseph. “When I com hom[e] I shall want to be with the Brethren [of] the first Presidency,” he wrote his wife in June 1840: “I long to see the faces of my friends again in that Country once more” (Brigham Young Letter to Mary Ann Young, 12 Nov 1840, Blair Collection). In October he asked Mary Ann how the Church felt about Brother Joseph, “our Moses that the Lord has given us.” Word had circulated that Joseph foresaw that some would forsake him and seek his life. “I shall be glad when [the] Church understand things and Lern [Learn] that the Lord is God and he will takcare [take care] of his own work, and Moses will do the work the Lord tells him to do” (Brigham Young letter to Mary Ann Young, 16 Oct 1840, CA). For his part, Brigham Young was anxious to return to Nauvoo to help protect the Prophet and teach the Saints that truth.

After their return to Nauvoo in the summer of 1841, the Twelve enjoyed a new relationship with Joseph Smith and the First Presidency. At a special August conference called for the purpose, the Prophet placed the Quorum of the Twelve next to the First Presidency to oversee the entire Church, a position earlier suggested by revelation but never before put into practice (see Esplin, “Joseph, Brigham” 310-12). From this point forward, the apostles served as Joseph Smith’s right hand in every important endeavor, and, as president of that quorum, Brigham Young became an even closer confidant, friend, and advisor. Joseph Smith turned over to President Young and his associates responsibilities ranging from missionary work and settling immigrants to constructing the temple and publishing the Times and Seasons. Even with those responsibilities that he continued to control more directly, the Prophet often sought Brigham’s help. When the first full temple ordinances were given in May 1842, for example, Brigham and Heber were among the small number of participants, a measure of their closeness to the Prophet and the trust he had in them. In all things, Brigham Young did what Joseph asked. He also continued to observe the Prophet closely and to learn from him. After three years of such devoted and intimate discipleship in Nauvoo, Brigham Young was qualified to lead when the Prophet was murdered in 1844.

Brigham Young was not emotionally prepared for the Prophet’s death, however, nor was he anxious to lead. Driven not by ambition but by a desire to serve the Lord and His prophet, he seems not to have contemplated life without Joseph. His fondest wish was to serve Joseph, not to succeed him. For Brigham Young, as for many of the Saints, the death of Joseph Smith was an unexpected blow and a great personal loss.

Even though the Prophet had commented both publicly and privately that his time was short and that once his mission was finished he had no promise of life, as with the apostles of old surprised by the death of Jesus, President Young and the Twelve had not fully understood, and Joseph’s death came as a traumatic shock (Esplin, “Joseph Smith’s Mission” 304-09). Intellectually and spiritually Brigham came to understand that it was necessary for the martyrs to seal their testimony with their blood, but emotionally, accepting the loss took a very long time. Perhaps he even blamed himself. Even years afterward he insisted that if the Twelve had been in Nauvoo they might have prevented the tragedy, for they would not have let Joseph and Hyrum go back to Nauvoo and into the hands of enemies.

Brigham Young was in New England with Orson Pratt when he learned of Joseph’s death. Shocked by the terrible news, Brigham smashed his hand against his leg in dismay—not just at the loss of a friend and prophet but at the loss of the keys Joseph possessed. He felt, he said later, “as tho my head wo[ul]d crack.” Just as suddenly he understood that the Lord had guided Joseph to prepare for this day: “it came like a clap—the keys of the K[ingdom] r here” and somehow it would be all right (Brigham Young Papers, Minutes 12 Feb 1849).

Once back at Nauvoo, Brigham’s inclination was to quietly join the Church in mourning the tragic loss. “There was more than 5 barels of tears shed,” he wrote to his daughter Vilate, and his own emotions demanded time for more of the same (Brigham Young Letter to Vilate Young, 11 Aug 1844, CA; the phrase following the one quoted is “I cannot bare to think any thing about it”). He had no inclination to step forward and declare himself Joseph’s successor, a word he would never use, nor could anyone take the place of Joseph, the Lord’s Anointed, the Seer, the Revelator, the Founding Prophet of this Dispensation. But Sidney Rigdon’s insistence on pressing his own claims forced Brigham to act without delay. In the clipped phrases of Thomas Bullock’s notes, President Young told the Saints:

I feel to want to weep for 30 days—& [only] then rise up & tell the people what the L[or]d wants with them—although my h[ear]t is too full of mo[u]rn[in]g [for?] bus[iness] trans[actions] at pres[en]t if the Ch[urch] is [to be?] org[anise]d & you want it—I will tell it for you (Bullock Minutes, 8 Aug 1844)

But first he turned to rumors that Joseph and Hyrum were not the only leaders targeted by anti-Mormon enemies: “I don’t know whe[the]r theyll take my life,” he commented, and he confessed that he did not care, for “I want to be with the man I love.” Nonetheless, recognizing that the Saints “are like chil[dren] without a fa[the]r,” he tried to reassure them. “I have spared no pains to learn my lesson[s] of the K[ingdom]” from the Prophet Joseph, he declared, and they could rest assured that “J[oseph] has laid the found[atio]n” and they, the Twelve, would build upon it (Bullock Minutes).

Other more polished accounts convey additional details of Brigham Young’s remarks to the grief-stricken Saints, like this from Wilford Woodruff:

For the first time in my life for the first time in your lives . . . do I step forth to act in my capacity in connexion with the quorum of the Twelve as Apostles of Jesus Christ unto the People and to bear of[f] the keys of the Kingdom of God in all the world. And for the first time are you Called to walk by faith not by sight. For always before you have had a Prophet as the mouth of the Lord to speak to you. But he has sealed his testimony with his Blood. . . . The Prophet Joseph has lade the foundation for a great work, and we will build upon it. . . . I will ask who has stood next to Joseph and Hiram? I have and I will stand next to him. We have a head and that head is the Twelve and we can now begin to see the necessity of the Apostleship. (2:435-37; the last two sentences quoted are crossed out in the original, perhaps by a later editor)

Another recorded:

The Twelve are appointed by the finger of God! Here is Brigham have his knees ever faltered? Have his lips ever quivered? Did he ever flinch before the bullets in Missouri? Here are Twelve, an independent body who have the keys of the Priesthood, the keys of the Kingdom to deliver to all the world. This is true So help me God. . . . You cannot appoint a Prophet, but if you let the Twelve remain & act in their place the keys of the Kingdom are with them, and they can manage the affairs of the Church & direct all things aright. (Minutes of a Special Meeting)

The vote of course, was nearly unanimous for the Twelve and the keys of the priesthood which they held. Brigham Young summarized the day in his journal: “I lade before them the order of the Church and the Power of the Priesthood. . . . the church was of one hart and one mind, they wanted the twelve to lead the church as Br Joseph had dun in his day” (Brigham Young Diary, Aug 1844). This, he said in a letter to his daughter Vilate “is our indespencable duty to due” (Brigham Young Letter to Vilate Young, 11 Aug 1844, CA).

“Joseph, the Temple, and the Twelve” became a rallying cry; they would continue with the temple and all that it represented, just as Joseph would have done. To apostates and dissenters, Brigham Young had but one message: Joseph lived and died a Prophet. He was not fallen or rejected of God but inspired to the end. And, promised Brigham, the Twelve would build on the foundation Joseph laid, not selected from Joseph’s rich legacy the things they liked but carrying out all the measures of Joseph.

The priorities established by Joseph Smith, including both finished the Nauvoo Temple and moving West, governed the actions of the Twelve under Brigham Young. Though neither enemies nor even most of the Saints yet understood, the Church would be leaving Nauvoo for the West—but not until the Saints could receive their blessings in the Nauvoo Temple as Joseph had directed (see Esplin, “A Place Prepared” 96-97). In the meantime, when Illinois canceled the Nauvoo Charters, even the city—renamed the City of Joseph—became a memorial to the fallen prophet.

Even though the Prophet had set the priorities, had left the Twelve keys of authority, and had instructed them in many particulars, new circumstances soon brought new questions. In the past Joseph himself had fielded such questions, but what now? By January 1845, for example, it began to appear that the Saints could not finish the temple without bloodshed. Joseph and Brigham had both declared that the temple was so important that they would finish it, if necessary, as had Israel anciently, with a sword in one hand and a trowel in the other. But facing the real probability of violence occasioned second thoughts: did the Lord expect them to finish the temple even if it meant bloodshed? Unable not to consult with Joseph, “his” prophet, Brigham turned directly to the Lord. “I inquaired of the Lord whether we should stay here and finish the templ the ansure was we should” (Brigham Young Diary, 24 Jan 1845; for a more detailed discussion fo the setting and the decision, see Esplin, “Brigham Young” 107-08).

And what about the West? The Prophet Joseph had long looked toward moving the Church to a place of refuge in the West, where, isolated from enemies, it could mature in safety. The when was clear: once the Saints were endowed in Nauvoo. But where? From Joseph Smith and his own prayer and study Brigham Young understood generally, but the Prophet had left no detailed blueprint, let alone a map. Where in that vast wilderness of the Rocky Mountains and Great Basin was the right place, and how would they find it? Again, with Joseph gone, Brigham had no where to turn but to the Lord. After fasting and much prayer in his temple office, Brigham Young received a vision. He was not given a map or a description of the route but he beheld in his mind’s eye the “right spot” so that he would recognize it when he got there (Esplin, “A Place Prepared” 100-01).

Revelation was essential if the church were to survive, of course, and Brigham Young knew that he and his brethren held the necessary keys and that the Lord would not abandon them. Indeed, during the trying last months in Nauvoo, he had the faith to defend the Saints by the power of special prayer, as Joseph had taught them, rather than using the Nauvoo Legion, but that’s another story (Esplin, “Brigham Young and the Power of the Apostleship” 109 ff). Still, the confidence that God was with them did not take away the pain of losing Joseph as leader, counselor, and friend. In his new responsibilities more than ever, Brigham Young felt the loss of Joseph to whom he had long turned for advice. And now, amidst difficulties, in addition to seeking guidance and blessings of the Lord, Brigham longed the more for the Prophet. Not surprisingly, on more than one occasion his friend and spiritual mentor continued to counsel and comfort him through dreams and visions.

In Nauvoo, a year following Joseph Smith’s death, President Young was inundated with concerns and labors. Finishing the temple, preparing for a move to the West, the providing daily guidance and leadership occupied every waking moment. At this time, when he especially needed such counsel, he noted in his journal: “This morning I dreamed I saw brother Joseph Smith and as I was going about my business he says brother Brigham dont be in a hurry—this was repeated the second and third time, when it came with a degree of sharpness” (Brigham Young Diary, 17 Aug 1845). He similarly received advice from Joseph in 1848 in connection with “new beginnings” in the Salt Lake Valley, and on other occasions.

The most dramatic and important such experience occurred in Winter Quarters, February 1847, less than two months before President Young set out for the Rockies. Moving the Saints across Iowa had required more time and resources than Brigham Young had ever imagined. For a time it seemed as if the whole Church was mired, both literally and metaphorically, hub-deep in the spring prairie mud. The experience overwhelmed him, drained him and forced him to confront his own (and all human) limitations. He had long known that without the overseeing hand of God the Saints had neither safety nor promise, but now after exhausting his own physical and emotional reserves to little avail, he understood more than ever the need for God’s intervention. And he longed for Joseph to counsel him and to reassure the people.

Illness seized him during the night of 16 February and the pre-dawn hours of 17 February, a sickness so severe that he “fainted away, apparently dead for several moments” and, wrote John D. Lee, “it was with much ado that he could be kept from falling asleep to await the resurrection morn” (Lee Diary, 17 Feb 1847). Only those who die and go through the veil could know how he felt, he said two weeks later, adding that “I know that I went to the world of spirits” (Stout 1:238). However, it was not given him to immediately remember the details of what he saw there: “All that I know, is that my wife told me about it since.” She reported that his first words upon being revived were that he “had been where Joseph & Hyrum was” and that “it is hard coming back to life again” (Ibid; clerk of the high council, Stout first recorded Young’s remarks as part of the minutes and then recopied the account into his own diary).

Revived and returned to his bed, Brigham Young fell asleep and dreamed, and when he awoke, he called for writing materials. “In my dream I went to see Joseph,” he wrote. He found him sitting by a large window looking “perfectly natural.” Brigham took him by the hand, kissed his cheeks, and asked him why they could not be together as before. Joseph arose from his chair and “looked at me with an earnest and plesent countenance, spoak in his usual way it is all right. I then said to him I due not like to be a way from you. it is wright he replied we can not be together yet, we shall be by en by[.] but you will have to do things with out me a while and then we shall be together again.” Brigham then addressed Joseph as his mentor in the priesthood, one who knew the Saints better than he did. “the Bretheren [especially Brother Brigham!] have grate anxiety to understand the law of adoption or sealing principles and. . . . if you have a word of councel for me I should be glad to receive it.” The counsel was very simple: “be sure to tel[l] the people to keep the spirit of the Lord” (Brigham Young Holograph, 17 Feb 1847).

The interview over, Brigham turned and saw Joseph standing in the light “but where I had to go was as midnight darkness.” Because Joseph insisted, Brigham “went back in the darkness” and awoke (Stout 1:238). As he described the experience not long afterward, “I have been with Joseph and Hyrum; it is hard to come back to life again.” President Young affirmed that he knew this experience was “from the Lord through Joseph” (Fielding Diary, 1847).

Though Brigham Young spoke of this several times in the weeks remaining before heading for the Rockies (see Fielding), he did not elaborate on its meaning to him. Undoubtedly it buoyed his spirits, confirmed him in his course, and provided still more evidence that he was on the Lord’s (and Joseph’s) errand and would not fail. Discouragement fled as winter passed into spring and the tempo of preparations for departure to the Rockies increased. Though still burdened by the demands of leadership and the magnitude of the challenge, Brigham was again at peace within.

Confidence renewed, President Young went on to find the “right place” in the American West where, for the next 30 years, he dedicated his life to building the communities of Zion. Ill in July 1847 and unable to accompany the first pioneers into the Valley, President Young left them detailed instructions to find the best spot in the northern end of the valley they could and then, in order to save the seed, to plant without delay. Although he came into the valley on 24 July, he made no public comment about the location until, on 27 July he dragged himself, still ill, to the top of what is now known as Ensign peak. From that perspective he could see with his eyes the scene he had seen in Nauvoo in vision, confirming that they had truly found the right place. Without delay he ordered the wagons moved to what would become the temple site and the next day he gathered the pioneers around and formally proclaimed that “this is the right spot.” He further affirmed that both he and Joseph had seen it before, and that it was the very place that the Lord had prepared (Esplin, “A Place Prepared 110-11).

Both to the original pioneers and to later Saints, Brigham Young made it clear that they had reached the place Joseph had looked forward to and where he had longed to be. The Prophet Joseph would have given anything to be there, declared President Young, but he was gone and it was now their duty to build what might have been had Joseph Smith lived to lead his people to the Great Basin, but it is certain that Brigham Young, for all his “temporal” abilities and for all his willingness to innovate in practical matters, held fast to the goals and the principles he continued to see himself as building on Joseph’s foundation and as carrying out “all the measures of Joseph.”

Clearly that was true of his personal supervision of the construction of the St. George Temple. He understood clearly that the Prophet Joseph’s charge to him regarding temple ordinances required a temple in the Great Basin, and as he grew older, he also realized that the Salt Lake Temple would not be completed in the years he had left. Fulfilling his temple-related mission required a temple on a smaller scale that could be built more quickly and St. George filled the requirement. In early 1877, just months before his death, he there completed his temple-related responsibilities—and one more commitment to Joseph.

President Young’s final major project in this life occupied the half-year between dedication of the temple and his death in August 1877. In a sweeping reorganization, he revitalized the Church from top to bottom, putting in place dozens of new leaders and also more complete organization and procedures that would help govern the Church for a century (see Hartley). This, too, he saw as connected to temple and to the mission and responsibility given him by Joseph Smith. That done, he was ready to meet both his Mentor and his Maker. According to his daughter Zina who was present, on 23 August 1877, Brigham Young quietly passed away after looking upward and saying the words: “Joseph, Joseph, Joseph” (Gates 380).

Throughout his life Brigham Young defended the character and testified of the uprightness of Joseph Smith.

I never preached to the world but what the cry was, “That damned old Joe Smith has done thus and so.” I would tell the people that they did not know him, and I did, and I knew him to be a good man; and that when they spoke against him, they spoke against as good a man as ever lived. (JD 4:77)

In 1853 Brigham wrote to an old friend, not a Latter-day Saint, this view of the Prophet Joseph:

In 1833 I moved to Ohio where I became acquainted with Joseph Smith, Jr, & remained familiarly acquainted with him in private councils, & public walks and acts until the day of his death, & I can truly say, that I invariably found him to be all that nay people could require a true prophet to be, & that a better man could not be, though he had his weaknesses; and what man has ever lived upon this earth who had none? (Brigham Young Papers, Letter to David B. Smith, 1 Jun 1853)

In this age when public figures so often fail to measure up in their private lives, the testimony of an intimate friend like Brigham Young is significant: “If ever Joseph got wrong, it was before the public, in the face of the eyes of the people; but he never did a wrong in private that I ever knew of” (JD 10:364).

As private friend and public associate, Brigham Young knew Joseph Smith as well as any man—a fact that adds weight to his testimony of Joseph as Prophet of God. “I am Brigham Young, an Apostle of Joseph Smith, and also of Jesus Christ,” he declared (JD 5:269). Joseph Smith was not co-equal with Christ, of course, but “Joseph Smith was the first Apostle of this Church, and was commanded of Jesus Christ to call and ordain other Apostles” and send them with authority to all the world. “These other Apostles are Apostles of Jesus Christ, and of Joseph Smith, the chief Apostle of this last dispensation” (JD 9:364).

The Savior was “the best man that ever lived on this earth, and my firm conviction is, that Joseph Smith was as good a man as any Prophet or Apostle that ever lived upon the earth, the Savior excepted. I wanted to say so much for Brother Joseph” (JD 19:364).

Bibliography

Esplin, Ronald K. “Brigham Young and the Power of the Apostleship: Defending the Kingdom through Prayer, 1844-1845.” Sidney B. Sperry Symposium, January 26, 1980: A Sesquicentennial Look at Church History. Provo, UT: Brigham Young Univ, 1980. 102-22.

_____. “The Emergence of Brigham Young and the Twelve to Mormon Leadership, 1830-1841.” Dissertation. Brigham Young Univ, 1981.

_____. “Joseph, Brigham and the Twelve: A Succession of Continuity.” BYU Studies (Sum 1981) 21:301-41.

_____. “Joseph Smith’s Mission and Timetable: ‘God Will Protect Me until My Work is Done.” The Prophet Joseph Smith: Essays on the Life and Mission of Joseph Smith. Eds. Larry C. Porter and Susan Easton Black. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1988. 280-319.

_____. “‘A Place Prepared’: Joseph, Brigham and the Quest for Promised Refuge in the West.” Journal of Mormon History (1982) 9:85-111.

Fielding, Joseph. Diary. LDS Church Archives.

Gates, Susa Young, and Leah D. Widstoe. The Life Story of Brigham Young. New York: Macmillan, 1931.

Hartley, William G. “The Priesthood Reorganization of 1877: Brigham Young’s Last Achievement.” BYU Studies (Fall 1979) 20:3-36.

History of the Church. 7 vols. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1980.

Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. 1854-86.

Kimball, Heber C. “History of Heber C. Kimball by his own Dictation.” Heber C. Kimball Papers. LDS Church Archives.

_____. President Heber C. Kimball’s Journal: Seventh Book of Faith- Promoting Stories. Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1882.

Lee, John D. Diary. LDS Church Archives.

Manuscript History of Brigham Young. Ed. Eldon J. Watson. LDS Church Archives.

Minutes of a Special Meeting in Nauvoo, 8 Aug 1844. LDS Church Archives.

Minutes, General Collection. LDS Church Archives.

“Reports and Minutes.” Times and Seasons (Jun 1840) 1:119-22.

“Reunion of Zion’s Camp Veterans.” Deseret News (19 Oct 1865).

Salt Lake High Council Record, 1869-72.

Smith, George A. “History of George Albert Smith.” George Albert Smith Papers. LDS Church Archives.

Smith, Joseph. Papers. LDS Church Archives.

Stout, Hosea. On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout. 2 vols. Ed. Juanita Brooks, Salt Lake City: Univ of Utah, 1964.

Woodruff, Wilford. Wilford Woodruff’s Journals. 9 vols. Ed .Scott Kenney. Salt Lake City: Signature, 1983.

Young, Brigham. Diary. LDS Church Archives.

_____. Holograph. LDS Church Archives.

_____. Letters. Blair Collection. Univ of Utah.

_____. Letters. LDS Church Archives.

_____. Papers (including Discourses and Minutes). LDS Church Archives.

Notes

[1] Brigham Young here conceded that his call “was indeed a mystery” even to him until he considered that perhaps the alternative to men like Heber and himself were “Big Elders” who knew so much that they could not be taught. “When I considered what consummate blockheads they were, I did not deem it so great a wonder” (JD 8:173).

[2] From Liberty Jail the Prophet wrote Young and Kimball that in the absence of the Presidency, it “devolves upon you, the Twelve” to lead out, which they already had begun to do (see Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and Hyrum Smith to Heber C. Kimball and Brigham Young, 16 Jan 1838, Joseph Smith Papers).