Called and Sent Forth: Electioneer Profiles

“I cannot do justice to the feelings of my heart, but acknowledge the tender mercies increasing my lot in company with these brethren . . . on my way to perform this important mission [to campaign for Joseph Smith], the faithful and acceptable performance of which involves my future prosperity in Church life.” —Franklin D. Richards, 27 May 1844.[1]

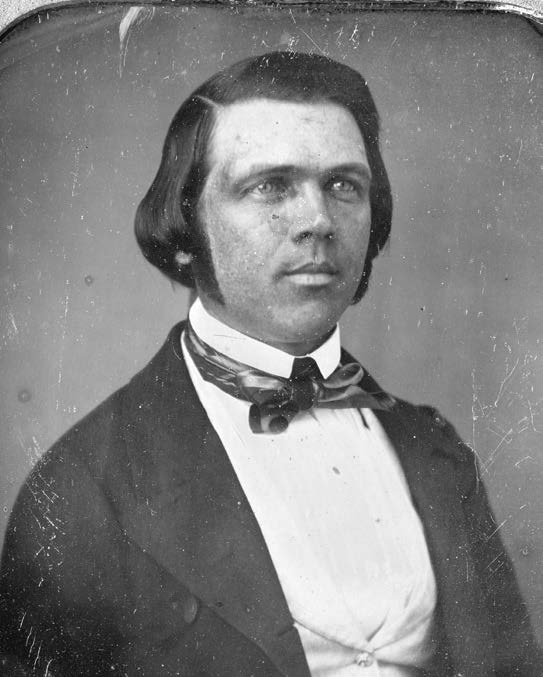

Electioneer Experience: Franklin D. Richards. At the April 1844 conference, twenty-three-year-old Franklin D. Richards and his brother Samuel, age nineteen, received assignments to electioneer with Amasa Lyman, copresident of the Indiana campaign. A month later, their uncle, apostle Willard Richards, insinuated that their campaigning missions would extend to England. The next day, 4 May, their twenty-five-year-old cousin Ed Pierson arrived in Nauvoo from Massachusetts. Accompanying him were missionary companions Elijah F. Sheets and Joseph A. Stratton, who had just completed an assignment back east in which they baptized more than one hundred converts. On 5 May Brigham Young formally extended the Franklin brothers’ mission to England, to be undertaken after the campaign. With the poor timing of a young husband, Franklin “revealed the fact of [his mission] appointment to the family” at a wedding celebration. The news shocked his young bride of less than two years, causing her “considerable sorrow of heart” to the point of “weep[ing] openly for a day or two.” On 13 May, Franklin, excited about his upcoming mission, went to hear “Elder Taylor lecture on Politics.”

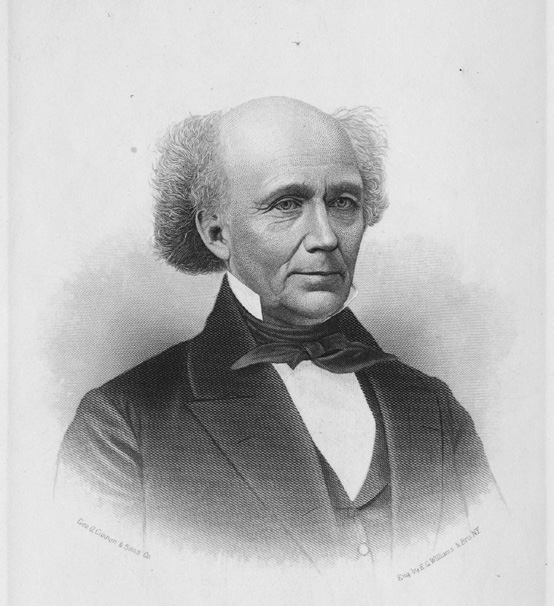

Franklin D. Richards was one of

Franklin D. Richards was one of

more than six hundred electioneers who campaigned for Joseph. Daguerreotype ca. 1850–60 by Marsena Cannon. Courtesy of Church History Library.

At the 17 May state convention for Joseph, Brigham ordained Franklin and Stratton high priests and gave them “letters of introduction and licenses.” Four days later at six o’clock in the morning, Franklin and fifty to sixty other electioneers boarded the steamboat Osprey to head to their various assignments in the East. The group included his brother Samuel, Stratton, Sheets, and Pierson, as well as apostles Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and Lyman Wight.[2]

* * *

The departure of this early group of electioneer missionaries illustrates church leaders’ efficiency in calling and assigning them, as well as the faithful responsiveness of those called. Franklin and Samuel Richards were among the original campaigners, yet their major change in assignment was met with excitement and firm resolve. Sheets, Stratton, and Pierson arrived in Nauvoo in early May expecting to spend the summer there, yet in less than three weeks they were headed back east as electioneers—Stratton to Delaware, Sheets to Maryland, and Pierson back to Massachusetts. Sheets wrote, “[The call] came rather unexpected to us, but we took co[u]rage.”[3] At St. Louis the group, having swelled to nearly one hundred, split in different directions. Their arrival was published in the St. Louis Era on 31 May. Newspapers from Maine to Louisiana and in the political centers of New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC, reprinted the news that the electioneer missionaries were coming. The Richards brothers, Stratton, Sheets, Pierson, and others took the steamer Louise Phillipe, destined for Pittsburgh, while the rest continued south.

Over the next several weeks, the Richards group crisscrossed the eastern states to their different assignments, working together, separately, or with new recruits. The latter included such men as Samuel H. Rogers and James H. Flanigan, who had already been proselytizing and had switched their efforts to campaigning. Occasionally they interacted with “field” electioneer missionaries like Thomas King and James Greig. These were Saints who joined the campaign effort in towns and cities across the nation, bringing with them their diverse abilities and local knowledge. Whether they were called in the April 1844 church conference, dispatched later from Nauvoo, transferred from proselytizing missions to campaigning, or recruited in the field, members of the growing cadre for the kingdom of God all shared a passionate desire to establish Zion and elect Joseph Smith as president of the United States.

The Call to Serve

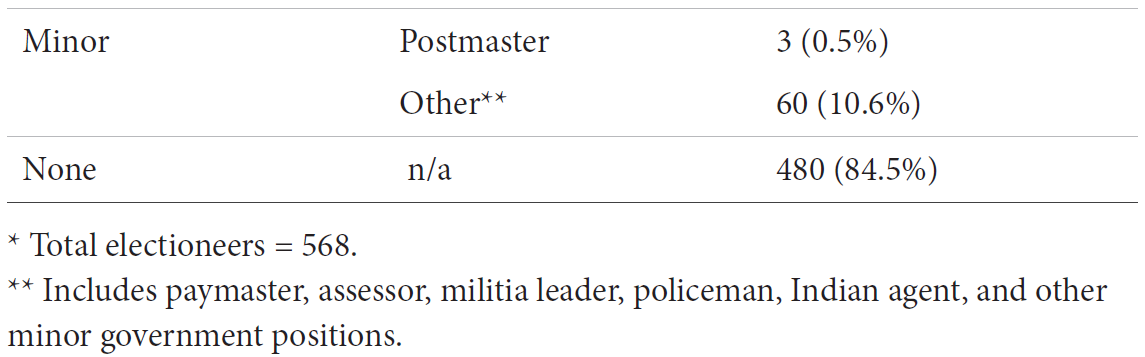

Between the request for volunteers on 9 April 1844 and the publishing of names in the Nauvoo newspapers a week later, the number of electioneer missionaries grew from 271 to 336.[4] Church leaders, looking for more, continued to recruit in Nauvoo and the surrounding communities. The search for help extended across the nation as scheduled conferences of the church netted recruits. In all, at least 611 electioneer missionaries campaigned in all twenty-six states and the territories of Wisconsin and Iowa.

In deciding who to count as an electioneer missionary, it is helpful to turn to a statement by campaign manager and apostle John Taylor. In the 28 February 1844 edition of the Nauvoo Neighbor, he urged the Latter-day Saints “to use all [their] influence at home and abroad for the accomplishment of [electing Joseph] . . . by lecturing, by publishing, and circulating his works, his political views, . . . and present[ing] him before the public in his own colors, that he may be known, respected, and supported.”[5] Obviously this appeal applied to those who would volunteer to be electioneer missionaries as well as to those who circulated Joseph’s political platform via church newspapers. It also applied to the chosen electors and delegates in states that held their conventions before the campaign ended. Naturally there are overlaps in these categories, but the vast majority of electioneer missionaries were the volunteers and those formally called as such. In any event, Taylor’s words clearly encapsulate the defining work of the electioneers.

The call to serve as an electioneer came in four distinct ways. The majority, 336 or 55 percent, volunteered or were selected during or just after the April conference. The Twelve asked the initial 271 to indicate which state they wished to labor in. Most chose their birth state; others chose a different state or expressed no preference. As a result of up-the-line review, a few had their initial choice crossed out and a different state written in. When the Times and Seasons list of 15 April appeared, most of the electioneers retained their requested assignments. The Twelve appointed one or two missionaries as presidents for each state. These men were responsible for publishing Joseph’s Views and holding periodic conferences to organize missionary work, assign individual electioneering tasks, and prepare state conventions in which electors would be chosen to represent Joseph in the electoral college.

English convert Alfred Cordon was among this first group of electioneer missionaries. On 9 April he recorded, “The conference was . . . then delivered into the hands of the Twelve and after a few remarks, they called upon all the brethren that could go and leave their families to go on a mission some for 3, 6, or 12 months. I had a strong desire to go out in the vineyard and labor, but I had no means of leaving my family, no, not for one month.” The next week on 15 April, Cordon went down to the docks to greet arriving English converts. There apostle Heber C. Kimball approached him “and told [him] that the Twelve had set [him] apart to go to the state of Vermont.” Surprised, Cordon replied he would go if that was their will. Arriving at home, he presented the matter to his wife, who faithfully replied, “Go and fulfill the work you are called unto.” Less than three weeks later, Cordon’s little family hunched over their table to eat the last of their food, unable to collect debts owed to Cordon. “I laid my hands on my wife and children and blessed them,” Cordon recorded, “[and] committed them to the keeping of the Eternal God, and on the fourth of May I started on my mission.”[6]

The second set of missionaries volunteered or received their calls in or near Nauvoo after the selection of the initial group. This second group consisted of 138 men, representing 23 percent of the total, including those working in and around Nauvoo in official campaign roles. Norton Jacob, David Fullmer, and Moses Smith were three such missionaries. They departed for Michigan on 14 May 1844 in a carriage with Charles C. Rich, president of the Michigan campaign. Curiously, like Rich, all three men had no previous connections to Michigan. However, they were all neighbors in northeast Nauvoo. Most likely, Rich, a member of the Council of Fifty, recruited them to serve with him. Jacob’s journal records that “at the spring conference 1844 Br. Joseph directed [that] all the elders of Israel should go into the vineyard. [Joseph] had previously been nominated for president of the United States, and part of the business of the elders would be to set forth his claims to the people.”[7] Charles Rich and David Fullmer had worked together on two high councils, and Moses Smith and Norton Jacob were close neighbors who spent their entire mission as companions.[8]

Those of the third group of electioneer missionaries were already serving missions away from Nauvoo and shifted their efforts to Joseph’s campaign. There were at least twenty-three such missionaries, representing 4 percent of the cadre. One was Crandell Dunn, who was serving in Michigan at the time he met up with cadre members Ezekiel Lee, Ira S. Miles, Samuel Bent, and Graham Coltrin in Kalamazoo, Michigan, on 28 May. Three days later apostles George A. Smith and Wilford Woodruff arrived and privately met with Dunn, giving him “instructions about Joseph Smith, [the] presidency, and his claims.” The next day Dunn was electioneering.[9] On 22 May, David S. Hollister, a member of the campaign’s central committee, found Irish convert and missionary James H. Flanigan in Wilmington, New Jersey. That night they gave a lecture on religion and politics. Thereafter Flanigan continued preaching politics throughout the Mid-Atlantic states.[10]

Samuel H. Rogers, Flanigan’s original missionary companion, had prepared him for such a transition. Having left Nauvoo together in April 1843, a year later they were working in different parts of the mid-Atlantic. On 21 April 1844, Rogers wrote to Flanigan to encourage his former companion: “Let us fight manfully for King Immanuel. Let all that we do be for the establishment of Zion.” Rogers then turned to his new focus of Joseph’s campaign. “[Let] us use our endeavors at the ensuing election to get General Joseph Smith the presidential chair of this nation,” wrote Rogers, “for he will fill the office as the chief magistrate with dignity and with greatness [and] honor to the nation [better] than any other man in the union. . . . Hereafter our motto is General Joseph Smith for president.” Flanigan wrote back, “Be faithful. The cause is good. . . . Vote for Joseph Smith as president.”[11]

The final subset of electioneer missionaries consisted of Saints from throughout the nation who either volunteered or were called by members of the cadre. One hundred and twelve, or 18 percent, of the electioneer missionaries were part of this group. Most often, cadre leaders found or called these men at the conferences held in the states. On 2 July 1844 in Boston, James H. Glines attended a “meeting of the priesthood by invitation,” where “much instructions and council was given, and the spirit of the Lord was made manifest.” Apostles Heber C. Kimball and Orson Hyde ordained Glines an elder. Then Brigham appointed him to a mission in his native New Hampshire “to preach the gospel and electioneer for Joseph Smith to be the president of the United States.” Glines headed for Haverhill, New Hampshire, and made appointments to “speak in favor of the election of the Prophet and of the powers and policy of the government of the United States.”[12] Milton Holmes and his father, the branch president of the Georgetown Massachusetts Branch, had for several years chosen not to gather to Nauvoo, much to the chagrin of church leaders. Yet in June 1844 Milton campaigned in Maine with former missionary companion apostle Wilford Woodruff. They had not seen each other for five years. Woodruff recorded, “It was quite a treat to enjoy his company once more.”[13]

Regardless of how they were called, many of the electioneer missionaries served with companions they knew. One hundred and thirteen, or 19 percent, worked with family members. Others companioned with close friends from Nauvoo or even former missionary companions. Erastus Snow even took his mother to visit family in Rhode Island on the way to his assignment in Vermont.[14]

A Season of Farewell

From 10 April 1844 (when Lorenzo Snow departed for Ohio) until mid-June, hundreds of electioneer missionaries left Nauvoo. Many, like Jacob Hamblin, recorded a sense of excitement. A lowly miner, Hamblin embraced the church in 1842 and became an elder. Hamblin wrote that during the April 1844 conference, “the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles called on the seventies that could leave their families and go on a mission to different parts of the United States to hold forth the prophet Joseph Smith as candidate for the president of the United States.” He remembered, “I felt anxious to go on such a mission.” Lyman Stoddard, who taught and baptized Hamblin, recommended him. Apostles George A. Smith and Amasa Lyman consequently ordained Hamblin a seventy. They “appointed [Hamblin] to the state of Maryland with Elder Stoddard.” Before leaving, Hamblin journeyed “to Wisconsin to see if [he] could convince [his] father’s folks of the gospel.” To his surprise they had moved to a farm in Iowa, just thirty miles northwest from Nauvoo. Unsuccessful in his attempt to bring them into the church, he returned to Nauvoo. “After a few days [he] started on [his] mission in company with John Myers, as Elder Stoddard had been sent to another source.”[15]

Levi Jackman remembered that “Joseph wanted a large number of elders to go out on missions, and I concluded to go.”[16] He left 5 June 1844 with Enoch Burns. Jacob Norton, writing eight years later, noted, “Br. Joseph [Smith] directed that all the elders of Israel should go into the vineyard. He had previously been nominated for president of the United States, and part of the business of the elders would be to set forth his claims to the people.”[17] James W. Phippin recorded a decade later that “at the April conference 1844 a call was made for volunteers to go into every state of the union to preach and spread abroad the views of Joseph Smith relative to the policy of the government.”[18] He departed for New York with Samuel P. Bacon on 18 April. Ira N. Spaulding remembered, “I was counseled to go into the state of Ohio, into Lucas and Richland Counties, amongst my friends to gain an influence among them in favor of President Joseph Smith being elected president of the United States.”[19]

Most electioneer missionaries left behind families, often at great sacrifice. Heber C. Kimball made it clear in the April conference that poverty or family concerns were not to hinder men from campaigning. James C. Snow and Alfred Cordon left their wives and children without even a pound of flour. They departed only after their wives insisted that God would provide for them.[20] Some electioneer missionaries sold family heirlooms or other valuables to finance their missions.[21] Before leaving, John Tanner handed Joseph the two-thousand-dollar note still owed him from Kirtland, saying, “Brother Joseph, you are welcome to it.” Joseph responded, “God bless you, Father Tanner; your children shall never want bread.”[22] Several missionaries were widowers who entrusted their children to the care of neighbors or friends, or simply left them on their own. John Blanchard left behind nine of his eleven children, aged three to twenty, in order to fulfill his mission. A widower for the second time just two months previous, Jacob Morris left his two children behind. More than a dozen of the missionaries were newlyweds, including some who married just weeks and even days before departing. More than seventy electioneers left wives who either were pregnant or had newborn children.[23]

Thirteen cadre members took their wives with them, and at least four of the wives gave birth during their husbands’ missions.[24] Jacob Gates, Lewis Robbins, and Crandell Dunn had their wives accompany them on their earlier preaching missions that were now focused on campaigning for Joseph Smith.[25] David L. Savage took his young wife Mary to help her deal with the recent loss of their first child.[26] The most intriguing couple to go was Moses and Naomi Tracy, who took with them their four children, ages two through ten. When Moses received his call, Naomi desired to accompany him and let her parents and in-laws meet their grandchildren for the first, and possibly only, time. Moses counseled with Joseph, who not only sanctioned Naomi’s going but also told Moses she would “prove a blessing to him” during his mission. Joseph was correct. Naomi, an educated schoolteacher and naturally more extroverted than her husband, helped teach the gospel and campaign for Joseph’s candidacy in New York.[27]

Missionaries expressed mixed emotions at saying goodbye to family and friends to head into an uncertain future. Several mentioned tender farewells at the waterfront of the Mississippi as they boarded steamboats.[28] John D. Lee perhaps best penned their feelings: “I took leave of our beautiful city on board of the steamer Osprey. . . . The importance of my mission came rushing into my mind, banishing grief and anguish!! . . . I lifted up my voice in supplication to the author of all good, demanding protection at his hand in behalf of myself and family. . . . I touched forth into the wide field of our labor perfectly calm and tranquil following my chief leader (Christ) and fearing no danger.”[29]

Only a handful of missionaries that were assigned to serve away from eastern Illinois never left Nauvoo.[30] William L. Watkins’s unnamed companion would not join him, so Watkins stayed in Nauvoo. Joseph L. Robinson, assigned to his native New York, was preparing to leave in early June when the Saints destroyed the press of the Nauvoo Expositor, a newspaper hostile to the church. Because of the tumult that followed, on 9 June during Sunday services “patriarch Hyrum Smith came upon the stand and said he did not want any more elders to go out upon this electioneering mission, as there was a storm brewing and he wanted all that was here to stay at home.” Robinson remained in Nauvoo, though he reported, “There were two brethren . . . who went to Brother Hyrum and begged to go as they were preparing to take their wives with them to New York and were anxious to go. He told them to go if they wanted to, so they went but never came back again.”[31]

Four electioneer missionaries assigned to Illinois returned to Nauvoo after the Expositor affair but before Joseph’s assassination: Daniel Allen, David Lewis, Stephen Markham, and Elijah Swackhammer. A few even returned from other states before Joseph’s murder. George W. Langley left sometime in May for his native Tennessee and, after baptizing a convert, returned to Nauvoo—all in two weeks. Jacob Gates and Robert T. Burton, serving missions before Joseph’s campaign, both returned before Joseph’s death—Gates in late May and Burton in early June. Council of Fifty member Jedediah M. Grant returned early from Michigan.

Electioneer Missionary Profile

The average electioneer missionary was thirty-five years old, three years younger than Joseph. The oldest, sixty-six-year-old Samuel Bent, was born just two years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The youngest was sixteen-year-old Charles H. Basset, who died in 1907. The last to pass away was Harley Mowrey (Morey) in late 1920 at the age of ninety-eight. Seventy-five percent of the electioneers were married. The average length of the electioneers’ church membership in 1844 was six years. The average field missionary, however, had been a member of the church only half that time. John W. Roberts and Ezra Thayre of Nauvoo were baptized within six months of the church’s organization. Field missionary Breed Searle chose baptism on 3 May 1844, in the middle of the campaign. He hosted a campaign conference a month later.[32]

Eighty-eight percent of the electioneers were born citizens of the United States. Two-thirds were born in the New England states, New York, Pennsylvania, or Ohio (not surprising since early missionary work centered in these states). Twelve percent consisted of immigrants, slightly higher than the contemporary national figure of 9.7 percent.[33] Missionary successes in Canada and Great Britain, coupled with the call for converts to gather to Nauvoo, explain the higher percentage. Of the immigrant electioneers, nineteen were born in Canada, fifteen in Great Britain, five in Ireland, and four in Germany. One-third of the electioneer cadre served in their birth states; others served in states where they had lived for a period of time. Wisely, campaign leaders assigned missionaries where they would have the most influence.

Surprisingly, only 36 percent of the campaigners had served a previous mission for the church. Yet Amasa Lyman and Erastus Snow had already served eight missions each. Those from the Nauvoo area had previous missionary service at a ratio of two to one compared to field missionaries.[34] Those that served previously had preached in neighboring towns and in distant states of the Union, in Canada, and even in Great Britain. Some, such as Benjamin Winchester in Pennsylvania and William I. Appleby in the Mid-Atlantic states, were fortunate to see converts baptized by the hundreds. Others, such as Joseph Curtis, struggled to spread the gospel. As he stumbled through his first sermon, the listeners coldly told him to stop preaching and go home. Many cadre members’ earlier missions resulted in the conversion of men who would become electioneer missionaries themselves. At least seventy men joined the church through the efforts of their future cadre colleagues, and some of these close relationships continued in the form of electioneer companionships.

Some electioneers experienced persecution in their previous missions. A mob beat Benjamin Brown and Jesse W. Crosby, leaving them for dead. Simeon A. Dunn also narrowly escaped death at the hands of a mob. Joel H. Johnson’s companion Joseph Brackenbury died from poisoning by enemies in 1832—the first Latter-day Saint missionary to die while serving. Johnson defended his dead companion’s body when members of the mob offered a reward for digging up and mutilating the corpse. Alfred D. Young’s life was spared when Davy Crockett’s nephew’s gun, pointed at his face, did not discharge.

Members of the electioneer cadre had diverse experiences and backgrounds. Daniel Allen was a descendant of Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allen. In fact, many electioneers had fathers and grandfathers who had fought in the Revolutionary War or the War of 1812. Ezekiel Lee and Reynolds Cahoon had served in the latter conflict. William G. Goforth’s father was a nationally renowned physician, Julius Guinard was the grandson of the president of the College of New Orleans, and the father of William R. R. Stowell was an eminent lawyer who argued before the Supreme Court. Others came from humbler backgrounds. Enoch Burns and John D. Lee suffered abuse and were deserted as children. William L. Watkins, who was seventeen at the time of the campaign, had suffered an accident fifteen years earlier that left him with a crippled leg. After his father died while immigrating to the United States, George D. Watt suffered from depression, experiencing regular suicidal thoughts.

These dissimilar upbringings merge in the stories of Elijah F. Sheets and Edward Hunter. A wealthy Quaker who lived in Pennsylvania, Hunter built what he named the West Nantmeal Seminary. It was a finely constructed building open to preaching for all denominations. To help work his five-hundred-acre farm, Hunter took in eight-year-old Sheets, an orphan from the age of six. Sheets lived with and worked for Hunter nine years before apprenticing to a local blacksmith in 1840. That same year both Hunter and Sheets joined the church. They began supporting its missionary work immediately, Sheets as a missionary and Hunter with his wealth.

Though diverse, the electioneer cadre constituted a unified group of mature, mostly married men trusted to serve because of their loyalty to Joseph and the church. A third of them had already proved faithful and diligent in missionary work. Church leaders specifically selected the electioneer missionaries to serve in areas of the nation they were familiar with so they could have increased influence among the people. In this way Joseph and the other leaders maximized the potential of the cadre to influence Latter-day Saints and the general electorate to embrace his platform and help propel him into the presidency. Joseph, confident of divine intervention to aid the cause, was in this election to win. He believed his cadre of electioneer missionaries would be the vanguard of that intervention.

Religious Backgrounds

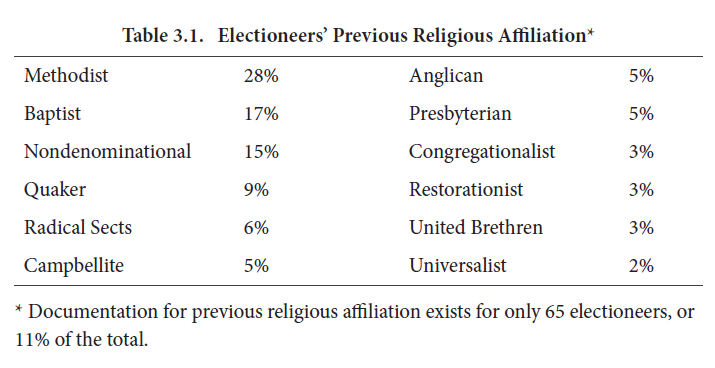

The electioneer missionaries came from varied religious backgrounds (see table 3.1). Several had been ministers in other faiths, and a significant minority had been Methodists, the denomination Joseph favored before his first vision. Coincidentally, several electioneers had spiritual struggles similar to Joseph’s while deciding which denomination to join, only to have a certain experience convince them to become Latter-day Saints.

Several electioneer missionaries converted to the church after experiencing visions or dreams or hearing spiritual voices. After reading the Book of Mormon for the first time, Samuel Bent saw a vision that showed him that the fulness of the gospel would be revealed in conjunction with the Book of Mormon and that he would be an instrument in proclaiming that message.[35] In a dream, Jonathan O. Duke witnessed his wife accepting the restoration of primitive Christianity, which he had denied. Startled by the vision, Duke immediately embraced the church.[36] On his way to South America in search of better health, Chapman Duncan heard a voice telling him to go no farther south than St. Louis or “you shall die.” Turning and seeing no one, Duncan continued his journey. At St. Louis, he heard the voice instruct him to “go to the place of gathering of my people [and] thou shalt live.” Confused and stranded on the wharf, Duncan introduced himself to a fellow passenger. The man, Philo Dibble, announced he was a Latter-day Saint and was traveling to Independence, Missouri, to gather with God’s people. Amazed, Duncan followed and was soon baptized.[37] Lorenzo Snow, a college-educated schoolteacher, struggled with his decision of whether to join the church and went into a grove of trees to pray. He recorded, “I had no sooner opened my lips in an effort to pray than I heard a sound just above my head like the rushing of silken robes; and immediately the Spirit of God descended upon me, completely enveloping my whole person, filling me from the crown of my head to the soles of my feet, and oh, the joyful happiness I felt!” [38]

Others experienced miraculous healing before or during baptism. Jedediah M. Grant joined the church after two elders healed his mother of rheumatism. An invalid for eight years, the mother of cadre brothers William, Joseph, and Thomas Woodbury was cured during their family’s baptism. Stephen H. Perry’s baptism healed him of thirty years of epilepsy. Joseph Shamp, a doctor, was unable to save his dying daughter. After a prayer by two missionaries, Shamp’s daughter regained health and survived. He demanded immediate baptism.

Cadre members embraced the concept of Zion and were fiercely loyal to its founder.[39] Israel Barlow rode two hundred miles to meet Joseph and was convinced he was a prophet. John S. Fullmer and Haden Church made similar journeys, coming to the same conclusion. Working as one of Joseph’s clerks, Howard Coray recorded, “I had many very precious opportunities” to view Joseph interacting with others. He believed Joseph “was equal to every occasion, that he had a ready answer for all questions.”[40] Personal contact was not necessary to fuel such devotion. Alfred Cordon, a convert in England, wrote Joseph in 1842, opening his letter: “Dear Brother, whom, having not seen, I love.”[41] The first English convert, George D. Watt, wrote that he believed in Joseph when his pastor spoke of him a year before missionaries appeared. When they did arrive, he outran other potential converts to the water to be the first baptized. John Tanner named his newborn son Joseph Smith Tanner without ever having met the prophet.

Despite a poor first impression, others also became loyal followers of Joseph. Edward Hunter was not impressed with Joseph when he heard him preach in the winter of 1839. Soon, however, he was taken with the devotion of Joseph and his missionaries. On a carriage ride he told the prophet, “How is it that I am attracted to those backwoods boys [missionaries]? I believe I would risk my life for them.” Within days he joined the faith.[42] After hearing Joseph preach, George C. Riser took his sick son to Joseph, who healed the boy. Afterward, Riser overheard the prophet joke with apostle Orson Hyde. Initially bothered by Joseph’s joviality, Riser wrote, “Upon reflection I could not think of anything they had said but what was innocent, and I felt that a prophet had a right to enjoy himself innocently as well as any other person.”[43] Convinced Joseph was God’s messenger, Riser received baptism in the frigid December waters of the Mississippi.

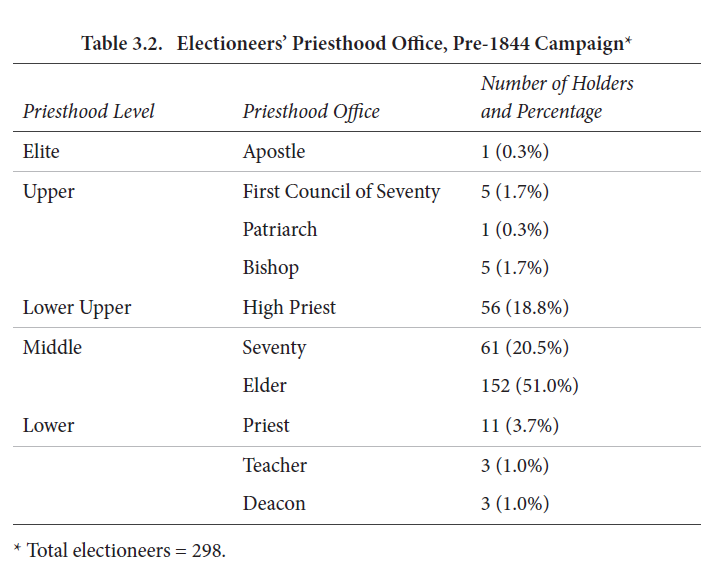

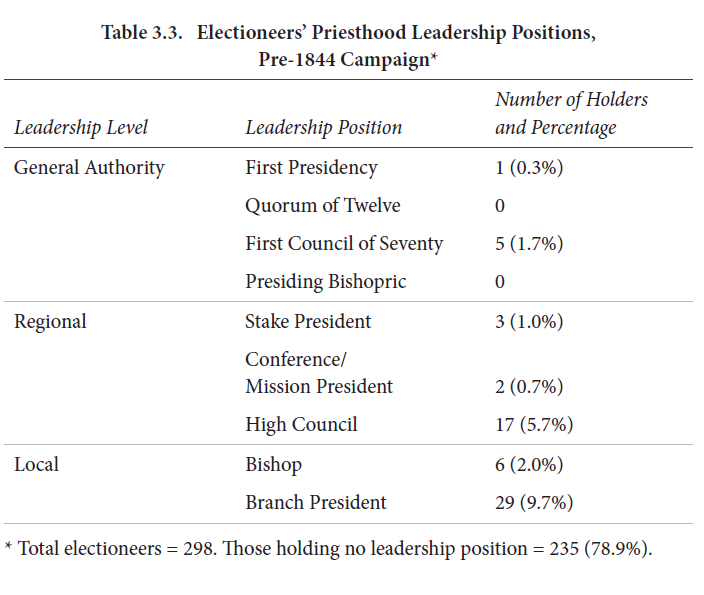

Before their missions, the electioneers each held a priesthood office in their newfound faith (see table 3.2). Every male deemed worthy through obedience and loyalty to the church, its leaders, and teachings received a priesthood office. More than 70 percent held at least the office of elder or seventy. Predictably, missionaries from Nauvoo, where many priesthood opportunities existed, held positions in the higher offices in larger numbers than was possible elsewhere. Conversely, field missionaries were overwhelmingly elders and priests. While priesthood offices were open to all worthy men, leadership positions were finite (see table 3.3). The vast majority of electioneer missionaries did not hold leadership positions before the campaign. Those who did were overwhelmingly leaders at the local level. Twenty-two percent of field missionaries were also local presiding elders. This is an indicator that Joseph’s campaign was successful in engaging the participation of local leaders and their congregations. Importantly, these were the men who knew conditions on the ground and were most likely to forge personal bonds with voters.

Some electioneers were not always steadfast in their loyalty to Joseph and the church. At least thirty received some type of discipline before the campaign. For example, Ezra Thayre was disfellowshipped for disobeying the law of consecration in 1831, excommunicated for apostasy in 1835, and considered “spiritually dead” in 1843.[44] Following the difficult times at Kirtland in 1837, James M. Emmett and others were disfellowshipped or excommunicated. After signing an affidavit for the state of Missouri against Joseph in 1838, William W. Phelps was excommunicated. Lyman O. Littlefield and Darwin Chase were brought before the Nauvoo high council for adultery. On 13 April 1844, just days after Jacob Shoemaker’s selection as an electioneer missionary in Pennsylvania, the Nauvoo high council disfellowshipped him for stealing George Morris’s axe and then beating him “violently.” The high council withdrew fellowship “until he [could] make good.”[45] All these men reconciled themselves to Joseph and the church in time to campaign. They had regained their places among the faithful and were considered safe in the cause. Expediency may also have figured into their calls since Joseph would need as many supporters as possible if his candidacy was to attract the attention of the masses.

Economic and Occupational Backgrounds

Joseph’s vision of Zion included a society with “no poor among them” (Moses 7:18). The prophet and other leaders struggled from 1831 to 1834 to establish the law of consecration. Among the wealthier electioneer missionaries, several followed this law to the fullest. Daniel Allen, upon joining the church in 1834, sold his farm in Huntsburg, New York, and gathered to Kirtland. There he gave the church the full six hundred dollars from the sale. John Tanner owned twenty-two hundred acres of farmland and a hotel in New York. Following his baptism, he sold everything, moved to Kirtland, and began living the law of consecration. He loaned what was left to Joseph, who never would be able to repay. Many of the less economically fortunate felt the same yearning for Zion. Joseph B. Bosworth preached about Zion declaring that “he had no property, but if necessary for her [Zion’s] deliverance he would sell his clothes at auction, if he might have left him as good a garment as the Savior had in the manger.”[46] Enoch Burns gave his last five dollars after his baptism. Dozens of the electioneer cadre lost everything when their stock in Kirtland’s Anti-Banking Safety Society became worthless. Despite many who strove to live the law of consecration, it failed. By revelation in 1838, Joseph replaced consecration with tithing.

However, many cadre members yearning for Zion continued to live consecration’s principles. After being baptized in 1841, David D. Yearsley sold all his possessions and moved to Nauvoo. There he built the only three-story brick house in town and donated the rest of his money by purchasing stock in church projects. That same year Edward Hunter moved from Pennsylvania to Nauvoo. He invested heavily in Nauvoo real estate and gave Joseph twenty-seven thousand dollars. In the spring of 1844, the prophet was financially strapped and facing numerous lawsuits. Stephen Markham sold his newly finished home, gave Joseph the twelve hundred dollars he received for it, and moved his family into a tent until he could build a cabin.

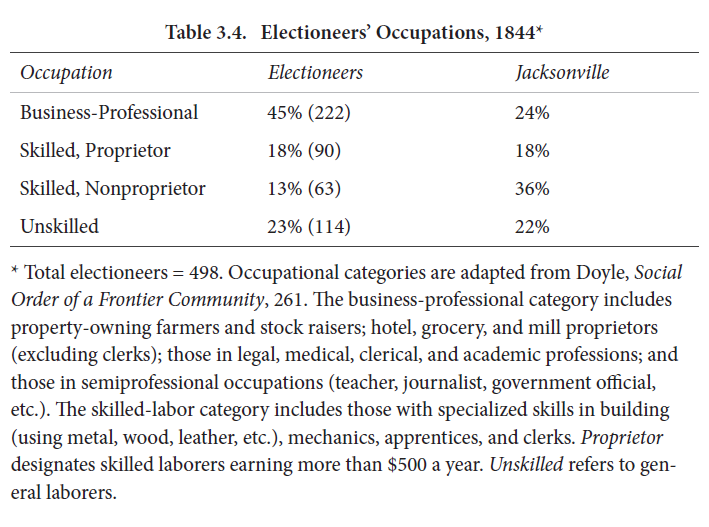

Cadre members came from diverse occupational backgrounds (see table 3.4). The largest occupational group among them was “business-professional.” One hundred and fifty landed farmers dominated this level, with most owning more than fifty acres of land. Some, like Samuel Bent and Increase Van Duezen, counted their property in the hundreds or thousands of acres. Others had different business occupations. David D. Yearsley owned two general stores and extensive farmland. Eighteen were thriving merchants. Ebenezer Robinson owned several rental properties and managed the Mansion House in Nauvoo. Isaac Chase operated one of the larger sawmills in Nauvoo, and George B. Wallace ran an extensive lumber and contracting business in Boston. Dan Jones owned a steamboat on the Mississippi, and Selah Lane owned a clipper that plied the Atlantic. Lucius N. Scovil operated Nauvoo’s largest bakery and confectionary. Several schools sprung up in Nauvoo owing to its burgeoning population, and fourteen electioneers were educators, with eleven of them living in or around Nauvoo. John M. Bernhisel and Levi Richards, personal physicians of Joseph, led a group of a dozen doctors, eight of them living in or near Nauvoo. John S. Reid and Lemuel Willard were the only lawyers among the electioneers. Henry Sherwood was Nauvoo’s marshal, and Jedediah M. Grant was the group’s only stockman.

With Nauvoo quickly emerging as Illinois’s second largest city, there was an urgent need for skilled craftsmen. Members of the electioneer cadre who owned their own shops and tools prospered. Howard Egan was Nauvoo’s premier rope maker. Daniel Allen ran a tannery and shoe store. Other cobblers with shops included Nathaniel Ashby and Henry Herriman. Jonathan Browning, a nationally recognized gunsmith, produced rifles carrying the inscription “Holiness to the Lord.” Dominicus Carter and Osmon Duel were among those with blacksmith shops. The constant construction was a boon to a small army of proprietor carpenters. The temple and finer homes provided work for the cadre’s stonemasons and brickmasons, such as Stephen H. Perry and Jonathan O. Duke. Coopers included Henry H. Dean and James C. Snow. James H. Glines and three others owned tailor shops. Other proprietor craftsmen included Levi W. Hancock (cabinetmaker), Elam Luddington (shipbuilder), Joseph L. Robinson (chair maker), Amasa Lyman (cutler), and Charles Warner (auctioneer).

Sixty-three cadre members were craftsman without the capital to own shops or businesses. Frederick Ott and John B. Walker used their cabinetry skills in the employ of others. Samuel W. Richards worked as a carpenter for his older brother Franklin. Elijah Swackhammer, George T. Leach, and Garrett T. Newell worked in printshops. Samuel Shaw was a steamboat engineer on Lake Michigan. Jesse W. Johnston worked for a blacksmith in Quincy, Illinois, earning money to attend medical school. Other cadre members included James W. Phippin (harness maker), Stephen Post (blacksmith), Moses Tracy (merchant apprentice), and Stephen Willard (mason). Some of the cadre’s immigrants fell into this category. English converts James Burgess and Alfred Cordon worked as a carpenter and potter, respectively. German convert George C. Riser was a shoemaker.

The final group, unskilled laborers, made up almost a quarter of the electioneers. William L. Watkins, a seventeen-year-old, crippled immigrant from England, remembered that upon his arrival in 1843, “Nauvoo was flourishing, although the [immigrant] saints were generally poor.”[47] Most unskilled laborers, while poor, found jobs working on the temple site and were paid meager wages from tithing dollars. Nauvoo could absorb the high level of unskilled labor because of the temple project, but the consistent lack of capital created an economic system based primarily on land wealth and limited opportunities for social mobility.

It is instructive to compare this occupational distribution with that of the nearby town of Jacksonville, Illinois. The primary disparity between the two towns is that Nauvoo had a higher percentage of “business-professionals,” while Jacksonville had a higher percentage of nonproprietor skilled workers. The reason for the difference was the communitarian values of Zion in Nauvoo, where land distribution and ownership was seen as the right of all who gathered there. Joseph and other church leaders facilitated this as much as possible by offering generous credit terms to members. As a result, almost half of the electioneer missionaries were landed farmers. In contrast, in Jacksonville, as was typical in frontier communities, wealth tended to remain with an early, smaller group of large landowners who persisted over time. Transient skilled and unskilled labor, representing almost half of Jacksonville’s population, typified frontier towns where young men were on the move, looking for their next opportunity.

Latter-day Saint field missionaries were an exception with 64 percent in the business-professional category, a significantly greater percentage than in Nauvoo and Jacksonville. This discrepancy is explained by the nature of the men whom leaders recruited in the mission field to campaign for Joseph. Many were local presiding officers of the church who were often called to these positions because of their wealth and local status—attributes that enabled them to influence the church’s local growth and to succor poorer members and traveling missionaries.

Participation in Privileged Temple and Marriage Practices

Before his death in June 1844, Joseph shared the temple endowment, the sealing ordinance, and the practice of plural marriage sparingly and only among those in his inner circle. Thus it is not surprising that the overall participation of electioneer missionaries in newly introduced temple ordinances and practices in Nauvoo was minimal. Just seven of them—John Bernhisel, Reynolds Cahoon, Amasa M. Lyman, George Miller, William W. Phelps, Joseph Young, and Levi Richards—received the endowment before the campaign. Cahoon and Phelps were the only electioneer missionaries sealed to their wives. However, of the thirty men known to practice plural marriage before June 1844, eleven belonged to the cadre of electioneers. They thus represented a majority of those who practiced plural marriage who were not general church authorities. These were the men Joseph trusted, and they were intensely loyal to him and his vision of Zion.[48]

Tried in the Crucible of Persecution

Wise and politically connected, Dr.

Wise and politically connected, Dr.

John M. Bernhisel was one of few

political veterans available to assist with Joseph’s presidential campaign. Photograph by George Q. Cannon and Sons (ca. 1890) of an undated engraved portrait by E. G. Williams and Bros. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Most of the electioneer missionaries had experienced persecution and suffering in Missouri. Like Joseph, they looked to the federal government for redress for the property, liberty, and lives that had been lost. More than three hundred of them sent affidavits that Joseph took to Washington, DC, in 1839 along his formal petition for redress of grievances. After the Saints’ surrender at Far West, dozens were physically beaten or arrested and saw family members succumb to exposure or suffer abuse, rape, or even murder. The mob whipped and arrested Samuel Bent, whose wife perished from exposure. Hiram Dayton, Jonathan Hampton, and Melvin Wilbur lost children. Missourians gang-raped Eliza Snow, Lorenzo Snow’s sister and future plural wife of Joseph. A mob split open John Tanner’s head, leaving him for dead. Others of the electioneer cadre were present at the Hawn’s Mill Massacre. Ellis Eames narrowly escaped while friends were gunned down around him. David Lewis saw his brother wounded and then executed. Franklin D. and Samuel Richards also lost a brother in the massacre. David Evans, Jacob Myers, and Joseph Young gathered up the dead bodies and hastily buried them in the community well.

The suffering in Missouri cast a shadow on the church, including hundreds of the electioneer missionaries. John Loveless recalled, “In this, I was an eyewitness to scenes that, until this day, make my blood run cold and would almost make me fight a legion; women ravished, men murdered, houses burned, property destroyed, the prophet and patriarch, with many others, taken and cast into prison.”[49] Jesse Johnstun recorded, “I would have willingly fought until the last drop of my blood had been spilt.”[50] Just like their prophet, cadre members never forgot the sufferings and injustices of Missouri. These sons, grandsons, and great-grandsons of the American Revolution grew frustrated at the trampling of their constitutional rights. As no redress or aid materialized, they become more disillusioned with government in all branches and at all levels. Zion was what they longed for, and government and politics seemed increasingly hostile to its fulfillment. These men were battle-tested and ready to contend for political change even before Joseph’s campaign called them to action.

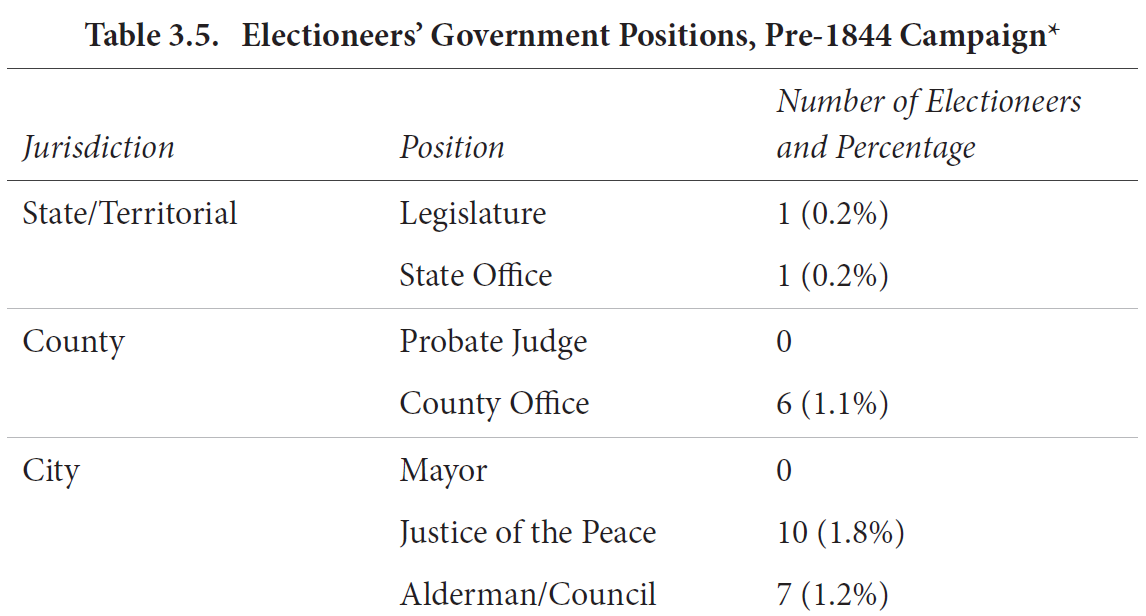

Political Involvement

Despite their political focus, few of the electioneers had been directly involved in politics or held office before the campaign (see table 3.5). In fact, eighty-five percent had never served in any political capacity. Although 11 percent had filled minor positions in government, fewer than 5 percent of them had city, county, state, or territorial experience—and even fewer had previous experience campaigning. This was common for the times, the 1840 election being historically the first in the nation with candidates and their supporters actively campaigning in large numbers.[51] However, the few electioneers who had previously campaigned had intense partisan convictions. For example, like most early Saints, Edward Hunter and Jonathan L. Heywood were staunch Jacksonian Democrats. When Hunter’s father, an influential Federalist in the Pennsylvania legislature, died, Hunter was offered his candidacy and could count on a sure election win. Yet he declined because of his democratic loyalties and opted to run for county commissioner instead. He handily won the office every time he ran. During Joseph’s campaign, Hunter represented Pennsylvania in the Illinois convention.

Heywood was a well-connected Democrat in Quincy, Illinois. After the election of the first Whig president in 1840, Heywood prepared to return Illinois and the nation to democracy in 1844. Still a year from his baptism, Heywood wrote his nephew in 1841 about the next national election: “The result may be doubtful, yet I still hope freedom will triumph over unlimited, irresponsible power.”[52] In the fall of 1843, Heywood used his democratic connections to offer Joseph Smith a quid pro quo arrangement with South Carolina senator John C. Calhoun and others. During the campaign, Heywood campaigned in Massachusetts with Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and other influential members of the electioneer cadre.

On the opposite end of Quincy politics was Jonathan Browning, a famous gunsmith and an ardent Whig who was elected several times as justice of the peace. He and his cousin Orville H. Browning were associates of young Abraham Lincoln and worked to elect him to Congress. They had also supported Henry Clay in his presidential aspirations. Jonathan’s conversion to the church was so unpopular among Quincy citizens that he moved his family and business to Nauvoo. Like Edward Hunter, Jonathan Browning worked as a delegate at Joseph’s Illinois convention.

John M. Bernhisel and William I. Appleby were also Whig activists. Bernhisel was an honors graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and an accomplished doctor when he embraced the church in the late 1830s. He served as a bishop in New York City before moving to Nauvoo and becoming Joseph’s personal physician and confidant. Bernhisel was a strident Whig, campaigning for William Henry Harrison in 1840. He was also friends with influential Pennsylvanian politician and judge John K. Kane (father of Latter-day Saint sympathizer Thomas Kane) and national Whig and future Republican leader Thaddeus Stevens. When his loyalties shifted to Zion, Bernhisel acted as an adviser during Joseph’s campaign and helped to edit the prophet’s Views. At the Illinois convention Bernhisel was a New York delegate and also served on the Central Committee of Correspondence for the campaign.

William I. Appleby grew up in New Jersey and became a respected schoolteacher. He spearheaded the county’s Whig campaign for William Henry Harrison. “I was active in the strife,” Appleby recorded, “using my influence and endeavors in behalf of Harrison’s election, attending political meetings, caucuses, &c.” In August 1840 an encounter with Latter-day Saint Alfred Wilson, who had just married Appleby’s niece, arrested his politics. “While in the height of my political zenith,” wrote Appleby, “[Wilson] remarked to me, ‘If you was only as zealous in the cause of God as you are in politics, you would make a first-rate preacher.’” Wilson’s words stung Appleby, a devout Methodist. After he was baptized by future electioneer colleague Erastus Snow, Appleby recorded the following in his journal: “My politics I laid by, and endeavored to seek after that which would be of more benefit.”

William G. Goforth was not a

William G. Goforth was not a

Latter-day Saint, yet his fame, political acumen, and newspaper left their mark on Joseph’s campaign. Potrait ca. 1840 by J. W. Taylor courtesy of Becky Pope.

As for the national election, to which he had previously devoted all his energies, Appleby observed: “I attended to my requisite duties, made out the returns &c., but took no part in politics, scarcely inquiring who was elected or who was not.” When Joseph’s campaign began, Appleby was already serving a mission in the Mid-Atlantic states. As Wilson had predicted, Appleby was a successful missionary and preacher. Traveling between Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware, Appleby left dozens of converts in his wake. On 5 May 1844 he met up with electioneer missionary John Wakefield. On hearing of Joseph’s candidacy, Appleby enthusiastically mixed his passions—religion and politics. That night he and Wakefield “both lectured on the powers and policy of the government &c.”[53]

Joseph’s cadre of electioneers also had three former political newspaper editors who helped spread his campaign message. William G. Goforth was a noted doctor from Belleville, Illinois, who had edited a small newspaper titled The Politician. In 1840 he led the Whig effort in Illinois to elect William Henry Harrison president. A prominent Freemason, Goforth spoke at the dedication of the Nauvoo Masonic Temple on 5 April 1844. Staying to attend the Saints’ conference, Goforth listened with interest at the call for electioneers. Owing to his experience in the previous presidential election and budding friendship with Joseph, Goforth was invited to participate in the prophet’s Illinois convention a month later. He became a delegate representing Illinois. During the campaign he split time between Nauvoo and Belleville in support of Joseph.[54]

As editor of The Prophet newspaper in New York City, Samuel Brannan advocated fiercely for Joseph’s candidacy. Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

As editor of The Prophet newspaper in New York City, Samuel Brannan advocated fiercely for Joseph’s candidacy. Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

William W. Phelps, Joseph’s prime

William W. Phelps, Joseph’s prime

veteran political confidant, helped

write Views and other political

literature and letters for the campaign. Daguerreotype ca. 1850–60 by Marsena Cannon courtesy of Church History Library.

Samuel Brannan spent a considerable part of his early adulthood in political newspapers. Born in Maine, he moved to Painesville, Ohio, in 1833 with his sister and her husband. They were baptized there, and Brannan apprenticed as a printer. When he received his inheritance, he ambitiously bought out his apprenticeship and invested in land. The financial crisis later known as the Panic of 1837 wiped out both his investments and his faith in the church. Eighteen and restless, Brannan went to New York City and sailed to New Orleans, where his brother lived. The two started a paper that failed after Brannan’s brother died of yellow fever. He next worked for, and briefly owned, the antislavery newspaper Indianapolis Gazette. Eventually returning to Painesville, he moved back in with his sister, retook his old job, and rejoined his former faith. When he briefly served as a missionary in Ohio, Brannan contracted malaria and almost died. At the time of Joseph’s campaign, Brannan was convalescing in New York City. He enthusiastically took an active role in helping to publish and edit the church’s newspaper in New York, The Prophet. By the fall of 1844 he was its owner and operator.[55]

* * *

The last, and most important, of the three editors was William W. Phelps. A founding member of the Anti-Masonic political party in 1827, Phelps edited two of the new party’s New York papers. After reading the Book of Mormon in 1831, he chose to walk away from politics and join the faith. Phelps moved to Missouri and by revelation started a newspaper. At a hearing in November 1838 after the Mormon Missouri War, he testified against Joseph and other leaders, prompting his excommunication in March 1839. Repentant, he rejoined the Saints in Nauvoo and became a trusted adviser again to the prophet. Phelps wrote most of Joseph’s political correspondence and edited Joseph’s Views pamphlet. His influence on Views was unmistakable and reflected his Anti-Masonry and Whiggish political ideas, “including anti-slavery views, prison reform, anti-elitism, more federal power to protect minorities, promotion of trade and currency, and fiercely anti-Van Buren.”[56] One of the Council of Fifty, Phelps was prominent at the Illinois convention and a member of the campaign’s Central Correspondence Committee.

* * *

Despite their varied backgrounds, the electioneer missionaries who campaigned for Joseph in 1844 coalesced around him and his Zion ideal and sacrificed to begin creating it. They gave all they had to their leaders even as their precious property and settlements were stolen, burned, or abandoned. Like other Saints at that time, most had not received temple ordinances or practiced plural marriage. However, of those privileged to do so in 1844, a significant number belonged to the electioneer cadre. While a majority had no experience governing or campaigning, the few who did brought significant experience to Joseph’s campaign.

In many ways, the electioneers represented a good cross section of 1844 Latter-day Saint men in Nauvoo and in the scattered branches of the church throughout the nation. So what makes them noteworthy? Unlike their fellow Saints, they chose to be electioneer missionaries, and they were committed not only to Zion but also to the uncertain consequences of seeking to establish a theodemocratic government in a democratic society. They had no qualms preaching and politicking, which was perhaps a step too far for other Saints. Although they came from different religious, economic, and political backgrounds, the men who campaigned for Joseph in 1844 had two things in common—a desire to build Zion and to see the prophet elected president. At what was often tremendous sacrifice, they tirelessly walked, preached, campaigned, and suffered for those causes. Their diligence began to generate a national interest in Joseph’s campaign. More importantly, their experiences molded them into a formidable group of capable men determined to bring about their prophet’s cherished religious, economic, social, and political Zion.

Notes

[1] Franklin D. Richards, Journal No. 2, 27 May 1844.

[2] The foregoing account is assembled from Franklin D. Richards, Journals 1 and 2, under the respective dates.

[3] Sheets, Journal, 6.

[4] “Special Conference,” Times and Seasons, 15 April 1844, 504–6. Margaret C. Robertson found fifty additional missionaries in her research, bringing the number to 386. See Robertson, “Campaign and the Kingdom,” 166n2. I found 225 more, bringing the total to 611.

[5] Taylor, “For President, Joseph Smith,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 28 February 1844, 2.

[6] Cordon, Journal and Travels, 3:178–79.

[7] Jacob, Reminiscence and Journal, 5.

[8] See Rich, Journal, 14 May 1844.

[9] Dunn, “History and Travels,” 1:41.

[10] See Flanigan, Diaries, 108–9.

[11] Samuel Hollister Rogers to Daniel Page, 24 April 1844.

[12] Glines, Reminiscences and diary, 39–40.

[13] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 2:416.

[14] Erastus Snow, Journal, 49.

[15] Hamblin, Record of the Life, 103.

[16] Jackman, “Short Sketch,” 21.

[17] Norton, Reminiscence and journal, 5.

[18] Phippen, “Autobiography,” 5–6.

[19] Spaulding, Autobiography, 199.

[20] Jenson, Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:794; and Cordon, Journal and Travels, 3:183.

[21] See, for example, Terry, Journal, 6 May 1844.

[22] See Tanner, John Tanner and His Family, 3.

[23] The information on Blanchard and Morris, as well as for other people in this chapter whose experiences are not keyed to sources in the notes, comes from my own genealogical research. I created a database of the 611 missionaries from an amalgamation of records from Susan Easton Black’s fifty-volume Membership of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, 1830–1848 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989), Ancestry.com, Personal Ancestral File, censuses, and other genealogical and family websites.

[24] The four wives were married to Lebbeus T. Coons, John Cooper, Uriel Nickerson, and Stephen Post.

[25] See Dunn, “History and Travels,” 1:22. Gates and Robbins took their entire families; see Robbins, Autobiography, 21–23.

[26] See Sudweeks, “Biography of David and Mary Savage,” 4.

[27] Tracy, Reminiscences and Diary, 27–29. I count Naomi among the electioneer missionaries because Joseph specifically directed her to accompany her husband on his mission and is the only wife on record to have campaigned for the prophet.

[28] For example, see Lee, Journal, May 1844–November 1846, 1; Smoot, Day Book, 1; and Erastus Snow, Journal 1835–1851, 47.

[29] Lee, Journal, May 1844–November 1846, 1.

[30] Four men listed in the 9 April 1844 minutes do not appear in the list printed in the Times and Seasons the following week: Jonas (Jonah) Killmer, Harrison Sagers, John C. Annis, and Moses Martin. I found no evidence that they left Nauvoo to campaign. In the minutes, Martin’s name appears without an assignment. Annis and Sagers had been involved in unauthorized plural marriages, bringing negative attention to the church in the previous months. While ultimately forgiven by the Nauvoo high council, they were not allowed to campaign—their names were simply crossed out. Another man, named Charles White, and Killmer had the word ordination written next to their names in the minutes. Although White did serve an electioneer mission to Massachusetts, there is no evidence that Killmer, who also was from Massachusetts, served.

[31] Quoted in Faulring, American Prophet’s Record, 489; see also Robinson, “History,” 93–95. At least ten men did not go to their fields of assignment: Joseph L. Robinson (New York), Amos Davis (Tennessee), David Evans (Virginia), John S. Fullmer (Tennessee), Jonathan Hale (Maine), Levi W. Hancock (Vermont), Jesse Walker Johnston (Ohio), William W. Phelps (Maryland National Convention), David H. Redfield (New York), and Cyrus H. Wheelock (New York).

[32] See “Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons, 15 July 1844, 580.

[33] Anderson, Encyclopedia of the US Census, 228.

[34] A mission here is defined as a period of one month or more preaching away from one’s hometown.

[35] See Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 1:368, s.v. “Bent, Samuel.”

[36] See Duke, Reminiscences and Diary, 1.

[37] See Duncan, “Biography of Chapman Duncan,” 2–3.

[38] Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:786–87, s.v. “Snow, Lorenzo.”

[39] See Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 190.

[40] Coray, Autobiographical Sketches, 2.

[41] “Letter from Alfred Cordon,” Times and Seasons, 16 May 1842, 795.

[42] Our Pioneer Heritage, 6:319.

[43] Riser, Reminiscences, 6–7.

[44] Jesse Wentworth Crosby, Autobiography, 23–24.

[45] Nauvoo Stake High Council Minutes, 13 April 1844.

[46] JSH, A-1:464 (21 April 1834).

[47] Watkins, “Brief History,” 1.

[48] See Buerger, “Second Anointing,” 23, where the eleven men are identified as John D. Lee, Joseph N. Bates Jr., Edwin Dilworth Woolley, Ezra T. Benson, Reynolds Cahoon, Dominicus Carter, Thomas S. Edwards, William Felshaw, Amasa Lyman, Erastus Fairbanks Snow, and Lorenzo D. Young. See also Smith, “Nauvoo Roots of Mormon Polygamy”; and Bergera, “Identifying the Earliest Mormon Polygamists.”

[49] Loveless, Autobiography, 2.

[50] Johnstun, Journal, 2.

[51] See Shafer, Carnival Campaign, vii, 149–54.

[52] Joseph Leland Heywood to his nephew, 28 July 1841.

[53] Appleby, Autobiography and Journal, 34–35, 117, 120.

[54] See Ford and Ford, History of Cincinnati, Ohio, 60; and Mulder and Mortensen, Among the Mormons, 14.

[55] See Roberts, Comprehensive History, 3:71.

[56] Van Orden, “William W. Phelps’s Service in Nauvoo,” 89–90.