Quest for the Presidency—and a Kingdom in the West

You have seen it announced that Joseph Smith is a candidate for the Presidency of the United States. Many think this is a hoax—not so with Joe and the Mormons. . . . Joe is really in earnest. —Correspondent of the Missouri Republican, 25 April 1844[1]

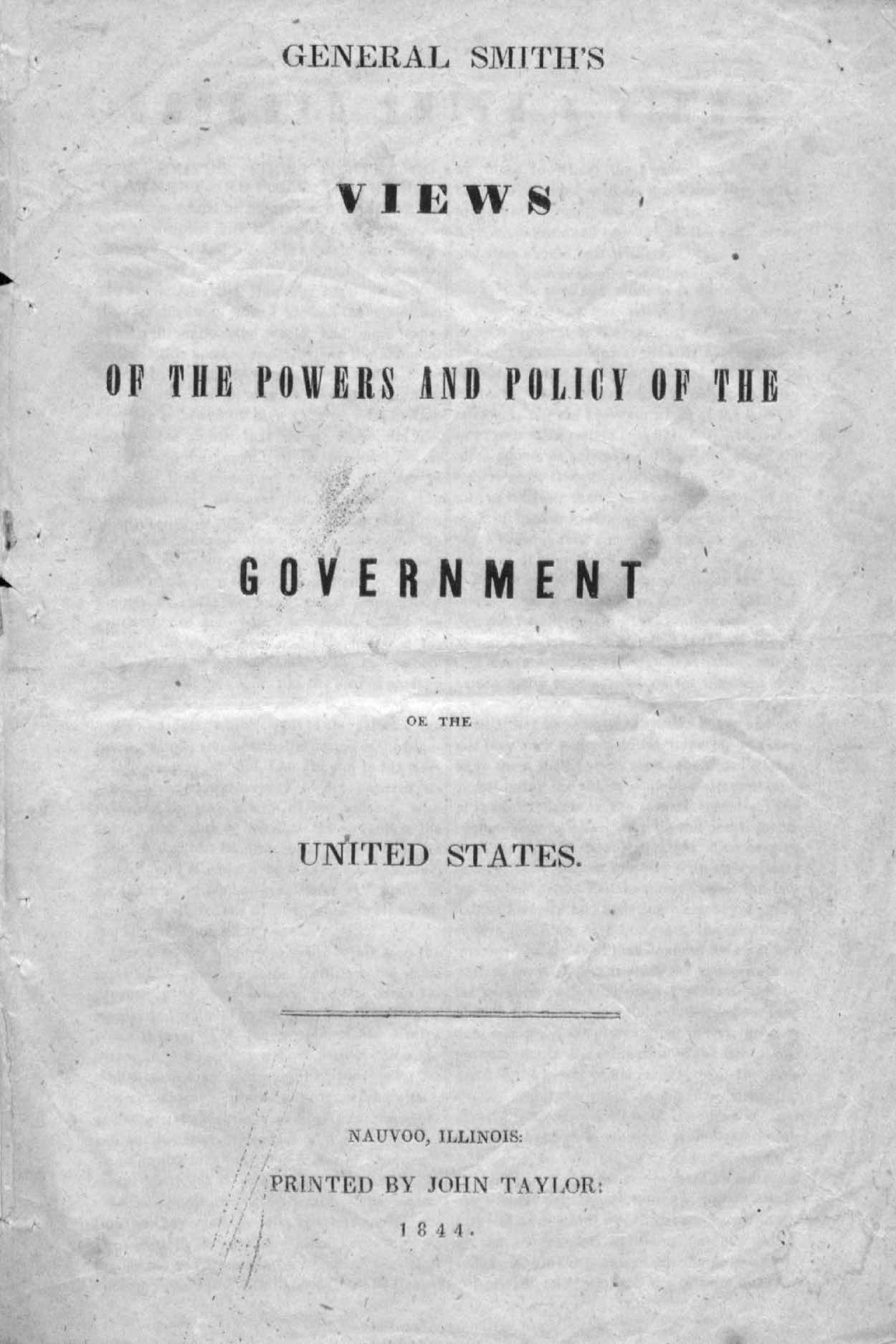

On 29 January 1844 church leaders nominated Joseph Smith for president of the United States. Joseph formulated his political views in a pamphlet titled General Joseph Smith’s Views of the Powers and Policies of the Government of the United States. He had it distributed throughout the country, and many local, regional, and national newspapers commented on it. In the ensuing months, church leaders organized a systematic campaign to elect Joseph. On 9 April, the final day of the church’s annual conference, they gave political instruction to more than a thousand men and asked for volunteers to become electioneer missionaries. Two hundred and forty-four responded immediately. Eventually more than six hundred were engaged in this new cause. Joseph’s campaign was unlike any other in the history of the nation: the prophet-leader of a new faith pursuing the presidency with a cadre of supporters canvassing the nation for him. In the backdrop of the campaign was Joseph’s evolving vision of theodemocracy, aristarchy, and the establishment of the kingdom of God.

“Who Should Be Our Next President?”

On 1 October 1843, just three days after Joseph created his “special council” of trusted associates mentioned earlier, apostle John Taylor, a council member and editor of the Nauvoo newspaper Times and Seasons, asked in print, “Who Shall Be Our Next President?” The editorial was undoubtedly a distillation of the council’s meeting. The election was “a question of no small importance to the Latter-day Saints,” declared Taylor. He rehearsed the injustices of Missouri and the Saints’ inability to receive redress from any level or branch of government. The special council had decided to enter national politics. “We make these remarks for the purpose of drawing the attention of our brethren to this subject, both at home and abroad,” Taylor wrote. Church leadership was ready to decide “upon the man who will be the most likely to render us assistance in obtaining redress for our grievances—and not only give our own votes, but use our influence to obtain others.” Taylor concluded, “We shall fix upon the man of our choice, and notify our friends duly.”[2]

Two nights later, Joseph and Emma Smith held a dinner party for more than one hundred couples, including those of the special council. As the evening ended, the attendees approved a list of resolutions. The contents of the resolutions delineated a discernible focus on a political Zion, with Nauvoo as its “emporium,” the Nauvoo Charter as its standard for “protection of the innocent,” the Nauvoo Legion as a “faithful band of invincibles” to defend it, and Joseph Smith—whether prophet, general, or mayor—the epitome of leadership.[3] Two weeks later, Joseph’s preaching became decidedly more political. “I am the greatest advocate of the Constitution of the United States there is on the earth. . . The only fault I find with the Constitution is it is not broad enough to cover the whole ground,” he declared. The later manuscript history added, “In my feelings I am always ready to die for the protection of the weak and the oppressed in their just rights.”[4]

Taylor’s article produced a response within a month. In early November Joseph huddled with members of the special council to discuss a letter from John L. Heywood, a Latter-day Saint and future electioneer missionary. A Colonel Frierson had offered Heywood his Democratic political connections to persuade Senator John Calhoun and Congressman Robert Barnwell Rhett, both of South Carolina, to present a Latter-day Saint memorial to Congress. In return, Democrats expected support for Calhoun’s expected run for the presidency.

Instead, Joseph wrote to each of the five likely candidates: Senator John C. Calhoun, General Lewis Cass, former vice president Richard M. Johnson, Senator Henry Clay, and former president Martin Van Buren. He asked, “What will be your rule of action relative to us as a people, should fortune favor your ascension to the chief magistracy?”[5] Joseph was looking for someone to rally the Saints to for quid pro quo protection. At this point, he was not committed to entering national politics himself. For example, in November Joseph received correspondence from newly baptized James Arlington Bennet, an influential easterner. Bennet offered to protect the Saints if the prophet helped him become governor of Illinois. Still dealing with accusations of political manipulation in the August election, Joseph forcefully declined: “Shall I, who have witnessed the visions of eternity, . . . shall I turn to be a Judas? . . . Shall I, who hold the keys of the last kingdom, . . . stoop from the sublime authority of Almighty God to be handled as a Monkey’s cat’s paw, and pettify myself into a clown to act the farce of political demagoguery? No, verily no!” [6]

In late December, letters from Cass, Clay, and Calhoun reached Nauvoo. Lewis Cass wrote, “I do not see what power the President of the United States can have over the matter, or how he can interfere in it.” Clay’s response also offered no assistance: “Should I be a candidate,” the senator penned, “I can enter into no engagements, make no promises, give no pledges to any particular portion of the people of the United States.” Calhoun opined, “According to my views, the case does not come within the Jurisdiction of the Federal Government, which is one of limited and specific powers.”[7] The other candidates never replied.

That same month Missourians brazenly kidnapped and tortured a Latter-day Saint and his son. This exponentially increased Joseph’s desire to protect himself and all Latter-day Saints.[8] He held a special council meeting, where it was decided to petition the federal government “to receive the city of Nauvoo under the protection of the United States Government.”[9] “I prophesy, by virtue of the holy Priesthood vested in me, in the name of Jesus Christ,” Joseph declared, “that if congress will not hear our petition and grant us protection, they shall be broken up as a government.”[10] A city ordinance created a police force to protect Nauvoo and the prophet. As anti-Latter-day Saint forces and threats grew, Joseph publicly lamented, “Is liberty only a name? Is protection of person and property fled from free America?”[11] One peril came from First Presidency member William Law. He accused Joseph of forming the police to intimidate him and others. Already economically and politically alienated, Law and his wife stopped attending Anointed Quorum meetings and protested plural marriage. Joseph dropped Law from the First Presidency, and estrangement over Zion between the two was complete. In a few months church leaders would excommunicate Law, who would respond by launching an opposition movement.[12]

As 1844 dawned, Joseph and the Saints were increasingly isolated politically.[13] On 2 January 1844, Joseph replied to Calhoun in the Nauvoo papers, and his caustic response was reprinted in newspapers nationwide. Whig papers delighted in Joseph’s castigation of Calhoun. “All men who say that Congress has no power to restore and defend the rights of her citizens,” he declared, “have not the love of the truth abiding in them.”[14] On 19 January, Joseph expounded on the Constitution and the candidates for president. He entertained some guests on 28 January and “lectured to them on politics religion &c.”[15] Politics—particularly national politics—was now on Joseph’s mind daily.

General Joseph Smith for President

The question posed in the Times and Seasons in October 1843—“Who shall be our next president?”—was answered by church leaders on 29 January 1844. Joseph met with the “Twelve Apostles, together with . . . Brother Hyrum and J[ohn] P. Greene . . . to take into consideration the proper course for this people to pursue in relation to the coming Presidential Election.” This group was fundamentally the protocouncil of “priests and kings” formed in the autumn. They decided it was “morally impossible for this people . . . to vote for the re-election of President Van Buren.” Nor could they vote for Henry Clay, whose counsel to them was to move to Oregon.[16] At this point Willard Richards moved “that we have independent electors and that Joseph Smith be a candidate for the next presidency and that we use all honorable means to secure his election.”[17] The council unanimously agreed. Joseph responded confidently:

If you attempt to accomplish this you must send every man in the city who is able to speak in public throughout the land to electioneer and make stump speeches, advocate the Mormon religion, purity of election, and call upon the people to stand by the law and put down mobocracy. David Yearsly must go. Parley P. Pratt to New York, Erastus Snow to Vermont, and Sidney Rigdon to Pennsylvania. After the April Conference we will have general Conferences all over the nation, and I will attend as many as convenient. Tell the people we have had Whig and democratic Presidents long enough: we want a President of the United States. If I ever get into the presidential chair, I will protect the people in their rights and liberties. I will not electioneer for myself. Hyrum, Brigham, Parley and Taylor must go. . . There is oratory enough in the church to carry me into the presidential chair the first slide.[18]

Joseph intended to send hundreds of men throughout the nation preaching and electioneering. He was already contemplating specific geographical assignments for the missionaries. His platform would be one of unity and universal protection of civil liberties. The April conference would launch a national campaign mobilizing Latter-day Saints to influence the electorate to vote for the prophet.

This was not a mere public relations campaign. The nomination called for independent electors eligible to represent Joseph in the electoral college, creating the necessary campaign infrastructure to have him elected.[19] To emphasize the blessing of heaven on the decision of that day, Joseph recorded what occurred that morning: “Captain White of Quincy. . . drank a toast, ‘May Nauvoo become the empire seat of government!’”[20] Before retiring that night, Joseph began dictating to William W. Phelps his Views pamphlet.[21]

Views called for unity and lamented how the Constitution’s promise of equal rights had been trampled by devious and immoral men: “Unity is power, and when I reflect on the importance of it to the stability of all governments, I am astounded at the silly moves of persons and parties to foment discord in order to ride into power on the current of popular excitement.” Joseph praised the wisdom of the early presidents, a quality he believed had been lost. “Now, oh people! people!” he pleaded. “Turn unto the Lord and live, and reform this nation. Frustrate the designs of wicked men.”[22]

He proposed reducing the membership and pay of Congress. Prison reform, stemming from his legal experiences in four states, was another tenet. Joseph also addressed the nation’s biggest obstacle—slavery. Through financial redemption, he proposed abolishing it by 1850. The sale of federal land would “pay every man a reasonable price for his slaves” and thus “break off the shackles from the poor black man, and hire him to labor like other human beings.” Joseph advocated a new national bank with branches in every state and territory. He also addressed the divided sovereignty of federalism and states’ rights, which had hampered the Saints’ efforts to obtain redress. More than any proposal, Joseph’s determination to give the federal government more power grew from the unredeemed sufferings of the Saints.[23] “Give every man his constitutional freedom and the president full power to send an army to suppress mobs. . . . The governor himself may be a mobber; and instead of being punished, as he should be for murder or treason, he may destroy the very lives, rights, and property he should protect.” The prophet supported manifest destiny—the doctrine that the United States was destined to stretch from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. He believed Oregon “belongs to this government honorably” and called on the Union “to spread from east to the west sea.” Joseph envisioned annexing not just Oregon but also, if they were willing, Texas, Mexico, and Canada.[24] He implored the people of the nation to “arise, phoenix like,” and “cheerfully help to [restore]” America’s greatness. He then added, similar to what he had declared on 29 January 1844 after his council unanimously agreed to his candidacy, “We have had Democratic presidents, Whig presidents, a pseudo-Democratic-Whig president, and now it is time to have a president of the United States.”[25]

Joseph’s electioneers distributed copies of this pamphlet throughout the nation. Photo by author. Document courtesy of Church History Library.

Joseph’s electioneers distributed copies of this pamphlet throughout the nation. Photo by author. Document courtesy of Church History Library.

Joseph saw his candidacy simultaneously as unifying, restorative, and inspired. By deploring factionalism while advocating policies each party cared about, he appealed to voters across the political spectrum. Unsurprisingly, his central theme was unity—the underlining principle of Zion. Whereas political parties fragmented and disenfranchised, he would unite. His campaign was also restorative. God had sanctioned the American nation and her Constitution prepared by “wise men . . . raised up unto this very purpose.”[26] Yet for Joseph, the nation and its leaders had become corrupted. “But . . . [it is] my determination to arrest the progress of that tendency . . . and restore the government to its pristine health and vigor.”[27] Finally, Joseph understood his campaign as part of a divine plan. “I would, as the universal friend of man, open the prisons, open the eyes, open the ears, and open the hearts of all people, to behold and enjoy freedom—unadulterated freedom; and God . . . should be supplicated by me for the good of all people.”[28] Heaven and earth combined as Joseph chose words he also used to describe the kingdom of God: “Make HONOR the standard with all men; . . . and the whole nation, like a kingdom of kings and priests, will rise up with righteousnes, and be respected as wise and worthy on earth, and as just and holy for heaven.”[29]

On 6 February 1844 John Taylor held a dinner party for the First Presidency, the ten apostles currently in Nauvoo, and their wives. With the groups enthusiastic about Joseph’s candidacy, the evening turned to “the propriety of establishing a moot congress for the purpose of investigating and informing ourselves on the rules of national intercourse, domestic policy and political economy.”[30] Willard Richards sketched out a hypothetical federal government. Brigham Young was president, with John Taylor as vice-president and Richards as the secretary of state. Other apostles and Sidney Rigdon found themselves in cabinet positions or in the senate. Richards listed other names for “members of the house,” representing each state and territory.[31]

The names read like a who’s who of future Council of Fifty members and other electioneer missionaries. Of the forty-two nonapostolic names, only five would not serve as campaign missionaries. Most would labor in the same state on the list. Church leaders were already discussing not only who their electioneers would be but also where they would campaign. At some point that night, Joseph advised against creating this “moot organization and congress” for fear of “excit[ing] the jealousy of our enemies.”[32] (A month later Joseph changed his mind and created more than a moot congress—he organized the Council of Fifty, the genesis of the kingdom of God on earth.)[33]

The men reconvened the evening of February 7 at Joseph’s office to discuss “means to promote” the coming campaign and finishing Views. The next day, 8 February, they held a public political nomination meeting in the assembly room above Joseph’s red brick store. William W. Phelps read Views, its first public reading. Joseph then declared, “I would not have suffered my name to have been used by my friends on anywise as president of the United States . . . if I and my friends could have had the privilege of enjoying our religious and civil rights as American citizens, even those rights which the Constitution guarantees unto all her citizens alike.” Since no governmental hand had assisted the Saints, Joseph decided “to obtain what influence and power I can, lawfully, in the United States for the protection of injured innocence.” He was willing to die to defend his people’s liberties: “If I lose my life in a good cause I am willing to be sacrificed on the altar of virtue, righteousness, and truth in maintaining the laws and Constitution of the United States, if need be, for the general good of mankind.”[34]

Some have used the statement “I would not have suffered my name to be used” out of context to argue that Joseph was not serious about his campaign. However, such language was common in contemporary politics where ambition for the presidency was a public faux pas. Furthermore, his words give the reasons for his campaign and reveal the ultimate price he was willing to pay—his own life.[35] His campaign was deadly serious. The apostles called for a vote in support of Joseph’s candidacy and platform. It was affirmatively unanimous. The next night a similar session was held for others who could not fit in the room the day before. A third meeting occurred the following week. An editorial in the Times and Seasons declared, “There is perhaps no body of people in the United States who are at the present more interested about the issue of the presidential contest than are the Latter-day Saints.” “Our course is marked out,” it continued, “and our motto from henceforth will be General Joseph Smith.”[36]

News of Joseph’s campaign disturbed many non–Latter-day Saint residents of Hancock County. The Anti-Mormon Party held a county convention and publicized a “wolf hunt” around Nauvoo on 9 March—a direct threat to Joseph. With the scarring scenes of Missouri in his mind, the prophet immediately countered. Assembling the apostles, he raised the subject of fleeing the country entirely. Joseph instructed them to send a company to California and Oregon to find a location “where [they could] remove to after the temple [was] completed, and where [they could] build a city in a day, and have a government of [their] own.”[37] This was a drastically different option than gaining protective political power through election. Joseph pragmatically began preparing the Saints’ withdrawal from the United States so they could establish their own government—the theodemocratic kingdom of God.

The Twelve selected men for the exploring company. “Jonathan Dunham, Phineas H. Young, David D. Yearsley, and David Fullmer volunteered to go; and Alphonzo Young, James Emmett, George D. Watt, and Daniel Spencer were requested to go.”[38] Ironically, except for Dunham, everyone in this original group instead became electioneer missionaries. Two days later Joseph instructed the Twelve to select others and stipulated that those selected must each must be a “king and priest” so that among the “savage nations” they would “have power to govern”—a direct allusion to second anointings. Joseph added, “If we don’t get volunteers, wait till after the election.”[39] Within a week twenty-four men enlisted to join the Western Exploring Expedition, as they named it. Thus Joseph simultaneously prepared to rally his followers and other voters to elect him president of the United States and to seek refuge in the West. [40]

Either option, the presidency or autonomy in the West, would provide the desired result—protection for Zion and her priesthood ordinances. On 25 February Joseph attended a meeting of the Anointed Quorum. They prayed that his Views “might be spread far and wide and be the means of opening the hearts of the people.” He then prophesied “that within five years we should be out of the power of our old enemies, whether they were apostates or of the world; and told the brethren to record it, that when it comes to pass they need not say they had forgotten the saying.”[41] He proved correct. In 1849 the Saints were safely creating Zion in the Great Basin. Joseph himself lay buried—a victim of assassination, largely because of his candidacy.

Church leaders mailed fifteen hundred copies of Views to the “president and cabinet, supreme judges, senators, representatives, principal newspapers in the United States, . . . and many postmasters and individuals.”[42] The Nauvoo Neighbor for 28 February carried the headline “Joseph Smith for President.” An article called for united campaigning: “It becomes us, as Latter-day Saints, to be prudent and energetic in the cause that we pursue, and not let any secondary influences control our minds or govern our proceedings.” Electing the prophet was now “an imperative duty,” requiring the Saints “to use all [their] influence at home and abroad for the accomplishment of this object.” They would succeed “by lecturing, by publishing, and circulating his works, his political views, his honor, integrity and virtue . . . and present him before the public in his own colors, that he may be known, respected, and supported.”[43] The cry “General Joseph Smith for President!” now became the primary mission of the church, its leaders, and its members.

A meeting of church leaders on 4 March 1844 nominated James Arlington Bennet as Joseph’s vice-presidential running mate. As a national author, previous regional newspaper editor, and noted philanthropist, Bennet had the gravitas Joseph sought. Four months earlier Joseph had vehemently declined Bennet’s political support. Then Joseph was dealing with the backlash of supporting his brother Hyrum’s revelation in the congressional elections. At the time the prophet wanted his name out of politics. Further, Joseph was most likely suspicious of Bennet and his motives. But in March everything was different: no national candidate was coming to rescue the Saints, Joseph was leading a serious campaign for the presidency and he and his associates were looking everywhere for political allies. Bennet now seemed more than palatable.

Writing to Bennet on the council’s behalf, Willard Richards revealed the thoughts of Joseph’s inner circle. He reported enthusiastic astonishment “at the flood of influence that is rolling through the Western States in his [Joseph’s] favor, and in many instances where we might have least expected it.” Joseph’s candidacy seemed only logical given his role as God’s prophet. “General Smith is the greatest statesman of the 19th century. Then why should not the nation secure to themselves his superior talents, that they may rise higher . . . and exalt themselves through his wisdom?” Bennet’s earlier desire to have Joseph help him become governor of Illinois was “mere sport, child’s sport.” “For who would stoop to the play of a single State,” Richards continued, “when the whole nation was on the board?”

While all nascent campaigns speak in confident tones, there was something different here—something divinely confident. Richards instructed Bennet: “If glory, honor, force, and power in righteous principles are desired by you, now is your time. You are safe in following the counsel of that man who holds communion with heaven; and I assure you, if you act well your part, victory’s the prize.” Success would occur as they “go to it with the rush of a whirlwind, so peaceful, so gentle, that it will not be felt by the nation till the battle is won.” Richards gave Bennet his campaign role. “Get up an electoral ticket—New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and any other state within your reach. Open your mouth wide, and God shall fill it. Cut your quill, and the ink shall flow freely.” A special conference would convene on 6 April in Nauvoo, and then “our Elders will go forth by hundreds or thousands and search the land, preaching religion and politics; and if God goes with them, who can withstand their influence?” Two days later, the Nauvoo Neighbor added Bennet’s name under Joseph’s on its front-page banner.[44]

In Nauvoo, conversation everywhere centered on politics, even at religious meetings. On 7 March 1844, Joseph, William W. Phelps (his chief political adviser), and apostle John Taylor (his campaign manager) addressed an audience of eight thousand at the temple site. Joseph announced, “We are Republicans and wish to have the people rule, but they must rule in righteousness. Some would complain with what God Himself would do.” The key for good rule was the righteousness of the people and the leaders—something the restored gospel produced. Phelps then read Views. The thousands assembled voted to support Joseph for the presidency “with one exception.”[45] Joseph famously declared: “As to politics, I care but little about the presidential chair. I would not give half as much for the office of president of the United States as I would for the one I now hold as lieutenant-general of the Nauvoo Legion. . . . We have as good a right to make a political party to gain power to defend ourselves,” he declared, “as for demagogues to make use of our religion to get power to destroy us. . . . As the world has used the power of government to oppress and persecute us,” he continued, “it is right for us to use it for the protection of our rights.” Joseph stated, “We will whip the mob by getting up a candidate for president.” He overflowed with confidence. “When I get hold of the Eastern papers, and see how popular I am, I am afraid myself that I shall be elected,” he proclaimed.[46]

The next day, church leaders received information that James Arlington Bennet was an immigrant from Ireland, making him constitutionally ineligible for the vice presidency.[47] Seeking a new candidate, they decided to write to Colonel Solomon Copeland, who had befriended the missionaries, including Wilford Woodruff, in Tennessee in the mid-1830s. The council instructed Woodruff to write a letter extending the invitation. Woodruff penned the document a week later. He outlined the Saints’ suffering in Missouri and their inability to get any redress. “We deem it no longer necessary,” he continued, “to use our influence promoting men to the highest offices of this government who will not act for the good of the people but for their own aggrandizement & party purposes.” Instead, Woodruff wrote, they would have their own candidate, “and that candidate is General Joseph Smith.” “And sir,” Woodruff continued, “the request I wish to make of you is to know if you are willing to permit us to use your name as a candidate for vice president at the next Election.” Woodruff included a copy of Views and invited Copeland to come visit Nauvoo. Copeland never responded.[48]

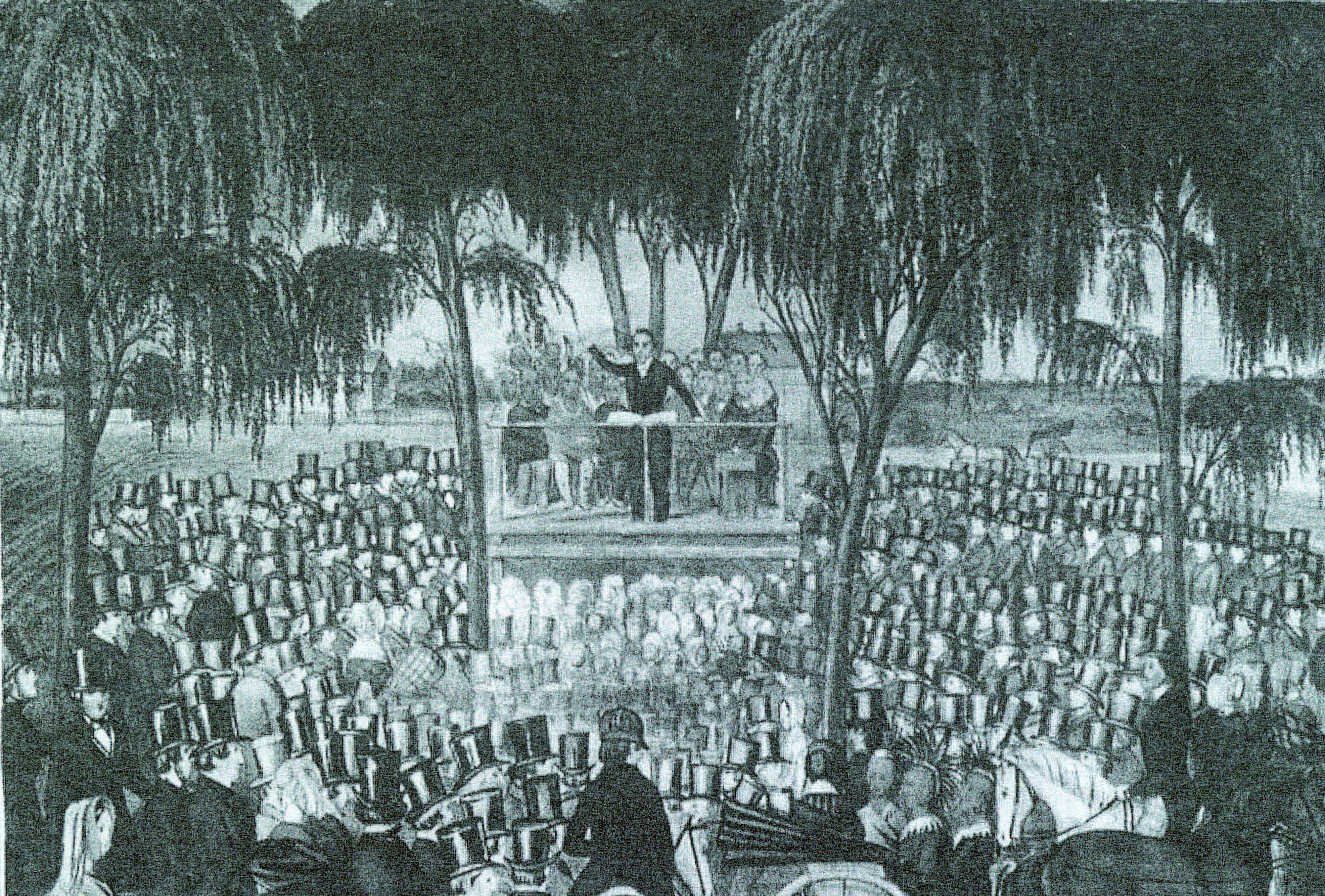

Engraving depicting the 6 April 1844 conference in Nauvoo, during which electioneer missionaries were called. Engraving ca. 1845 by Lloyd George (b. 1817) courtesy of Church History Library.

Engraving depicting the 6 April 1844 conference in Nauvoo, during which electioneer missionaries were called. Engraving ca. 1845 by Lloyd George (b. 1817) courtesy of Church History Library.

The Council of Fifty: The Campaign and the Kingdom of God

On 9 March 1844, Joseph spent most of the frustrating day in his role as mayor. In a rarity, the city council voted against Joseph on an issue. Toward the end of the debate, Joseph stated: “It was the principles of democracy that the people’s voice should be heard when the voice was just, but when it was not just it was no longer democratic, but if the minority views are more just, then aristarchy should be the governing principle; i.e., the wisest and best laws should be made.” [49] Rule by aristarchy was more sensible than government by the popular or mistaken. Joseph’s comments show he had decided the time had come to implement the revelation of almost two years earlier regarding the kingdom of God.

The next day, Sunday, 10 March, he preached on the need to obtain “endowments of the fulness of the Melchizedek Priesthood and of the kingdom of God,” a theodemocratic theme. Late that afternoon Joseph gathered the apostles and other members of the protocouncil at the Nauvoo Mansion. They read two letters from apostle Lyman Wight and Bishop George Miller, leaders of the small colony in Wisconsin that provided lumber for the temple. A federal Indian agent had blocked proselytizing and lumber procurement. From Wight and Miller’s viewpoint, the government was not only failing to protect Zion, now it was actively impeding it. They proposed increasing their colony and moving to the independent Republic of Texas. Joseph was intrigued. He asked the men around him, “Can this council keep what I say, not make it public?” They all assented. The time had come to begin organizing the kingdom of God. The group met again that night at the red brick store.[50]

The next day, 11 March, Joseph officially organized the kingdom of God in Henry Miller’s home. Twenty-three men were present, including eleven future cadre members. The council had three immediate purposes: to discuss the idea of colonizing within the Republic of Texas, to seek “the best policy . . . to obtain their rights from the nation and ensure protection for themselves and [their] children,” and to “secure a resting place in the mountains. . . where [they could] enjoy the liberty of conscience guaranteed to us by the Constitution.”[51] “All seemed agreed,” the minutes record, “to look to some place where we can go and establish a theocracy either in Texas or Oregon or somewhere in California.”[52] The council was informally called the Council of Fifty, but the official, revealed name was “The Kingdom of God and his Laws, with the keys and power thereof, and judgement in the hands of his servants. Ahman Christ.”[53] They admitted more members over the following days.

Every male to whom Joseph had given the second anointing and was thus a legitimate king and priest was placed in the Council of Fifty.[54] The theological underpinnings of temple ordinances were foundational to the council for at least two reasons. Anointed Quorum members had already made covenants not to discuss their endowments and so theoretically could be trusted. Also, members of the Council of Fifty needed the legitimate, governing authority of heaven that came from the temple ordinances. As the first meeting finished, the men of the council were elated. “The most perfect harmony prevailed during the whole of this council,” the minutes state. “Many great and glorious ideas were advanced,” William Clayton wrote in his journal, with the minutes agreeing that “the brethren all feel as though the day of our deliverance was at hand.”[55]

In the view of the early Latter-day Saints, while the establishment of the United States and its Constitution were inspired, their roles were merely preparatory to the kingdom of God. Orson Pratt later explained, “A republic was organized upon this continent to prepare the way for a kingdom which shall have dominion over all the earth to the ends thereof.”[56] On 12 May 1844 Joseph preached, “I calculate to be one of the instruments of setting up the kingdom of Daniel by the word of the Lord, and I intend to lay a foundation that will revolutionize the whole world.”[57] While most modern Saints interpret this verse to mean the church, that is not what Joseph was declaring. The context clarifies that he was referring to an actual kingdom, the one he established two months before. Joseph would make this distinction clear to the Council of Fifty: “The kingdom . . . is an entire, distinct and separate government,” he taught. It “was not a spiritual kingdom, but was designed to be got up for the safety and salvation of the saints by protecting them in their religious rights and worship.”[58] The expectation was that eventually the kingdom of God would spread theodemocracy to every nation and bring order to a chaotic world before and in the aftermath of the second coming.

The kingdom of God as Joseph envisioned it would tolerate and defend the religious freedom of the religions and societies that would persist in the first part of the Millennium.[59] Under this system of theocratic governance in a pluralistic society, people outside the church would “be admitted to the right of representation . . . and have full and free opportunity of presenting their views, interests and principles, and enjoying all the freedom and rights of the Council.”[60] To this end, Joseph included three “gentiles” in the council: Uriah Brown, Edward Bonney, and Merius G. Eaton. Three of fifty members certainly did not fully represent pluralistic participation, yet the token accommodation was made in good faith.[61] Joseph was adamant about securing religious freedom for all. He expressed hope that every man in the council would, when aged, be able say in retrospect that “the principles of intolerance and bigotry never had a place in this kingdom, nor in my breast” and would be “ready to die rather than yield to such things.” . . . “Only think! When a man can enjoy his liberties and has the power of civil officers to protect him, how happy he is.” Joseph was so animated as he finished his discourse that the two-foot ruler he was “pretty freely” using “broke . . . in two in the middle.”[62]

The Council of Fifty met once or more a week for the next two months. New members were added until their number reached fifty. The council sent ambassadors to Washington, DC, with petitions. They also sent Amos Fielding to England with unspecified overtures and Lucien Woodworth to Texas to negotiate establishing a Latter-day Saint colony in the Texas Republic. Reflecting the Council of Fifty’s belief that they were more than a body to protect the church within the United States, Orson Hyde referred to the council members as “stand[ing] on the summit of all earthly power,” and Parley P. Pratt referred to them as “the most exalted council with which our earth is at present dignified.”[63] They were “not tied to any country”[64] because the prophet was “already president pro tem of the world”[65]—“God’s messenger to execute justice and judgment in the earth.”[66]

During his sermon on 24 March 1844, Joseph announced that he had uncovered a conspiracy to kill him, his family, and other church leaders. He named William Law and others as conspirators. The enmity between Law and Joseph was now public. At some point in the council’s 26 March meeting, Joseph’s mood turned sober. Several of the apostles recorded two months after his death what they remembered of the prophet’s words:

Brethren, the Lord bids me hasten the work. . . . Some important scene is near to take place. It may be that my enemies will kill me, and in case they should, and the keys and power which rest on me not be imparted to you, they will be lost from the earth; but if I can only succeed in placing them upon your heads . . . I can go with all pleasure and satisfaction, knowing that my work is done, and the foundation laid. . . . Upon the shoulders of the Twelve must the responsibility of leading this church hence forth rest.

The record then states that Joseph and Hyrum Smith placed all the keys of authority on the Twelve. Joseph then continued: “I roll the burden and responsibility of leading this church off from my shoulders onto yours. Now, round up your shoulders and stand under it like men; for the Lord is going to let me rest awhile.”[67]

In retrospect, Joseph’s apparently self-evident declarations that “some important scene is near to take place” and “it may be that my enemies will kill me” were prescient.[68] The apostles may have remembered only the parts of his speech alluding to his possible death because it had in fact happened. No contemporary journals or other writings of that day, including the Council of Fifty minutes, attribute such sentiments to Joseph or mention any forebodings of approaching catastrophe. There did not seem to be serious concern about the prophet being killed. In fact, the events of the next three weeks would show the council members full of confidence in their plans to see him elected president. That the “important scene” would be Joseph’s death was only one possibility among many. And the statement that the Lord was going to let Joseph “rest awhile” could mean he would have some greater responsibility outside the church, such as his current position as chairman of the Council of Fifty, or even president of the United States.[69]

As April conference approached, Joseph and the Council of Fifty were excitedly engaged—far from the melancholy of impending doom. They coordinated Joseph’s presidential campaign, prepared for possible resettlement of Zion in the West, negotiated with other countries through ambassadors, and learned the ways of the kingdom of God so that they might become effective “kings and priests.” All of this created an electric atmosphere as the long-awaited April conference drew near. On the eve of the conference, Joseph held Council of Fifty meetings on 4–5 April, and some of the ideas discussed would exuberantly flow into the discourses of the conference.[70] Lurking in the background were enemies, political and otherwise, plotting the destruction of Joseph and his Zion.

April Conference 1844

The much-anticipated conference opened on 6 April 1844, the fourteenth anniversary of the church. Nauvoo swelled to almost twenty-thousand Saints. Sidney Rigdon spoke first and, unsurprisingly, made union of church and state his theme:

I recollect in the year 1830 I met the whole Church of Christ in a little old log house, . . . and we began to talk about the kingdom of God as if we had the world at our command. . . . The time has now come to tell you why we had secret meetings. We were maturing plans fourteen years ago which we can now tell. . . . When God sets up a system of salvation, he sets up a system of government. When I speak of government, I mean what I say. I mean a government that shall rule over temporal and spiritual affairs.[71]

Rigdon was straightforward: church and state were to become one. It was a topic that absorbed him. Not only had he addressed it in the Council of Fifty in a “spirited and animated manner,”[72] but he would return to it twice more in the April 1844 conference.

Next, apostle John Taylor spoke. He declared that the Founding Fathers and others created “kingdoms and empires that were destined to dissolution and decay.” In comparison, the Saints were “laying the foundation of a kingdom that [should] last forever—that [should] bloom in time and blossom in eternity.” To ensure his audience understood the gravity of the moment, he declared, “We are engaged in a greater work than ever occupied the attention of mortals.”[73] While some preaching took place throughout the day, there was no doubt what was on the minds of the leaders of the church—the theology and politics of governance.

The next morning, Sunday, 7 April, Hyrum Smith addressed the congregation. “We are now the most noble people on the face of the globe, and we have no occasion to fear,” he asserted. The reason for his exuberance, he declared, was that he had a “big soul.” The Saints all had big souls. “As soon as the gospel catches hold of a noble soul, it brings them all right up to Zion.” The prophet then stood. The congregation, amazed by what they had heard thus far, were about to be theologically stunned by the doctrinal crown of Joseph’s teachings. What began as a funeral sermon for the recently deceased King Follet became an astonishing announcement: “God himself was once as we are now, and is an exalted man, and sits enthroned in yonder heavens! . . . And you have got to learn how to be gods yourselves, and to be kings and priests to God, the same as all gods have done before you, namely, by going from one small degree to another, and from a small capacity to a great one; from grace to grace, from exaltation to exaltation.”[74]

The following day Joseph announced, “The whole of America is Zion, from north to south.”[75] The temple was to be completed so that “men may receive their endowments and be made kings and priests unto the Most High God.”[76] Zion was to grow throughout the Americas as endowed kings and priests built up branches and sent converts to Nauvoo for their endowments. This dovetailed with Joseph’s campaign platform to annex Oregon, Mexico, and Canada.

As these three days ended, Latter-day Saints understood that they had “big” and “noble souls”—big enough to one day become gods. Meanwhile, they were to become “kings and priests” through temple ordinances and to seek to convert the entire Americas. Furthermore, as the church grew, it was destined to govern not just spiritually but temporally. Church leaders would channel the feelings of exuberant eagerness at the conference into a determined, vibrant campaign for Joseph.

On the last day of the conference, 9 April, church leaders held the special meeting for the elders that the Nauvoo papers had announced for two months. Brigham addressed the congregation of more than eleven hundred. He challenged the elders to zealously build up the church and establish Joseph’s political views. “We are acquainted with the views of Gen. Smith, the Democrats and Whigs, and all factions. It is now time to have a president of the United States. Elders will be sent to preach the gospel and electioneer. The government belongs to God. No man can draw the dividing line between the government of God and the government of the children of men.”[77] Brigham roared, “This is a fire that cannot be put out. . . . We will turn the world upside down.”[78]

The previous evening Hyrum had announced that the church leaders “calculate to send out about 1000 of you. Put 1000 el[ders] together and you can raise a hell on earth. You will have a great deal of knowledge. We want you to be successful.”[79] Now Hyrum charged the potential missionaries to “[not] fear man or devil; electioneer with all people, male and female, and exhort them to do the thing that is right. We want a president of the U.S., not a party president, but a president of the whole people, . . . a president who will maintain every man in his rights.”

Hyrum’s call to action was buttressed by the desire to create both religious and political union. “I wish all of you to do all the good you can,” he declared. “We will try and convert the nations into one solid union.” He “despise[0] the principle that divides the nation into party and faction.” Hyrum charged the electioneer missionaries, in words reminiscent of his candidate brother two months earlier, “Lift up your voices like thunder; there is power and influence enough among us to put in a president.” Success would follow. “I don’t wonder,” Hyrum confidently finished, “at the old Carthaginian lawyer being afraid of Joseph Smith being elected.”[80]

Brigham again stood. He “requ[e]sted all who were in favor of electing Joseph to the presid[e]ncy to raise both hands.” All but one raised their hands. The audience spontaneously began “clapping their hands and gave many loud cheers” that echoed across the hilltop.[81] Never had there been more excitement in the leadership and ranks of the church than at this moment. The minutes record, “The dearest and biggest vote and the most unanimous vote that ever passed in the world went for Joseph to be president.”[82] When the audience settled, Heber C. Kimball announced that conferences would be set up in each of the states to campaign for Joseph and to select delegates for a national convention. Whereas leaders had earlier counseled missionaries to not depart until their domestic situations were settled, the urgency of the campaign changed everything. “A great many of the elders will necessarily have to leave their families,” Kimball said, “and the mothers will have to assume the responsibility of governing and taking care of the children to a much greater extent.”[83] Amasa Lyman (a future cadre member) echoed the same sentiments two days later in a council meeting. He did “not think any sacrifice too great to make for the glories of this kingdom, even if it requires us to leave father, mother, wives, and children.”[84]

Brigham then called for volunteers to preach and electioneer. “A great company moved out and returned to the right of the stand and were numbered.”[85] It took an hour and a half for the clerks to process their names and information. In the end they recorded 271 names, covering three pages of minutes. Names of those who would serve for twelve months were written first, followed by those volunteering for six months, and then those serving three months. The leaders then adjourned the conference for an hour. When it reconvened, the names “were read and corrected” and “places [were] assigned for their missions.”[86]

* * *

The nucleus of Joseph’s electioneer missionaries was now prepared, called, and assigned. However, the cadre was smaller than expected. Church leaders had hoped for closer to one thousand. Only a quarter of the elders in the meeting had stepped forward. If the numbers greatly disappointed them, however, they did not express it at the time. In fact, Joseph recorded that the April conference had “been the greatest, best, and most glorious five consecutive days ever enjoyed by this generation.”[87] The time had come for the electioneer missionaries to “turn the world upside down.”[88]

Notes

[1] Correspondent of the Missouri Republican from Nauvoo, Illinois, 25 April 1844, as quoted in Baker, Murder of the Mormon Prophet, 190. This was reprinted in newspapers across the nation.

[2] JSH, E-1:1771; emphasis added; also Times and Seasons, 1 October 1843, 343–44.

[3] JSH, E-1:1744 (3 October 1843).

[4] JSJ, 15 October 1843; and JSH, E-1:1754 (15 October 1843).

[5] Joseph Smith to Martin Van Buren et al., 4 November 1843.

[6] JSH, E-1:1778 (13 November 1843); also Joseph Smith to James Arlington Bennet, 13 November 1843.

[7] For Cass’s response, see Lewis Cass to Joseph Smith, 9 December 1843. For Clay’s response, see JSH, F-1:28 (15 November 1843). Clay’s letter was not made public until after his nomination as the Whig candidate in May 1844. For Calhoun’s response, see JSH, E-1:1845–46 (2 January 1844).

[8] On the kidnapping, see JSJ, 6 December 1843.

[9] JSH, E-1:1798 (8 December 1843).

[10] JSJ, 16 December 1843.

[11] JSH, E-1:1804 (14 December 1843).

[12] See Bitton, Martyrdom Remembered, 1; and JSH, E-1:1857 (8 January 1844).

[13] For Joseph’s desire to reach out to the non–Latter-day Saint community, see Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 227–30.

[14] See JSH, E-1:1849.

[15] JSJ, 26 January 1844.

[16] See JSH, E-1:1869.

[17] JSJ, 29 January 1844.

[18] JSH, E-1:1868–70; emphasis added. There are a few details in this account that are not in Joseph’s journal of the same date. For clarity of language and the fact that those who filled in the gaps were present that day, I have used this manuscript source.

[19] The Joseph Smith Papers’ historian Spencer McBride has recently come to the same conclusion. See McBride, “Joseph Smith’s Presidential Ambitions,” 21–30.

[20] JSJ, 27 January 1844.

[21] The pamphlet was Joseph’s, but it was primarily written by W. W. Phelps. Joseph asked Phelps three days earlier to write a response to President Tyler’s recent annual address to Congress. Undoubtedly, Phelps had been thinking or writing about many of the items that would eventually be in the pamphlet. See Tyler, “Message of the President of the United States,” 1–4; and Nauvoo Neighbor, 27 December 1843, 1–2. John M. Bernhisel also seems to have contributed to the pamphlet. See JSH, E-1:1895 (20 February 1844).

[22] Smith, Views, 4, 8.

[23] Smith, Views, 8 passim.

[24] Smith, Views, 10.

[25] Smith, Views, 10, 11; emphasis in original.

[26] Doctrine and Covenants 101:80.

[27] Smith, Views, 8.

[28] Smith, Views, 12; emphasis added. Joseph told a group of people when asked who he was that “Noah came before the flood, I have come before the fire.” As reported by Abraham H. Cannon in Cannon, Diaries, 16:30.

[29] Smith, Views, 9; emphasis added and original capitalization preserved.

[30] Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 159.

[31] See Richards, “Proposed plan for a moot organization and congress.”

[32] Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 159–60.

[33] See Council of Fifty, Minutes, 11 March 1844, in JSP, CFM:40.

[34] JSH, E-1:1886 (8 February 1844). In a touch of irony, on this day when Views was first publicly read, Joseph’s journal records, “Held Mayor’s court, and tried two negroes for attempting to marry white women; fined one $25. and the other $5.” JSJ, 8 February 1844.

[35] See JSH, E-1:1886 (9 February 1844); and Taylor, “Who Shall Be Our Next President?,” Times and Seasons, 15 February 1844, 439. Church historian B. H. Roberts argued that Joseph’s candidacy was not serious; see Roberts, Comprehensive History, 2:209. His conclusions are now seen as outdated.

[36] Times and Seasons, 15 February 1844, 440, 441.

[37] JSJ, 20 February 1844.

[38] JSH, E-1:1896–97 (21 February 1844).

[39] JSJ, 23 February 1844.

[40] Seventeen of the twenty-four would serve as electioneer missionaries. Most had not been anointed “kings and priests.” Joseph may have been planning to give them the second anointing.

[41] JSH, E-1:1898 (28 February 1844).

[42] JSH, E-1:1898 (27 February 1844).

[43] JSH, E-1:1900 (1 March 1844). The 1 March 1844 edition of the Times and Seasons also carried the banner “Joseph Smith for President.”

[44] Willard Richards to James Arlington Bennet, 4 March 1844, as found in JSH, E-1:1904 (4 March 1844). Bennet is not to be confused with James Gordon Bennett, the famous contemporary editor of the New York Herald.

[45] JSH, E-1:1908 (7 March 1844).

[46] JSH, E-1:1912 (7 March 1844).

[47] This information about Bennet’s immigrant status proved to be false. He was born in New York, the son of Irish immigrants. See Wilford Woodruff to Solomon Copeland, 9 March 1844.

[48] There is no evidence that Solomon Copeland or his wife was ever baptized. Two of their slaves, Lewis and Robert Copeland, did join the church in 1836. See “Academy Tennessee Branch,” Amateur Mormon Historian (blog). Some have assumed Solomon was a Latter-day Saint; see Winkler, “Mormon in Tennessee,” 48.

[49] Nauvoo Stake High Council Minutes, 9 March 1844.

[50] JSJ, 10 March 1844.

[51] JSH, E1:1928 (10 March 1844). Original members were Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, Willard Richards, Parley P. Pratt, Orson Pratt, John Taylor, George A. Smith, William W. Phelps (cadre), John M. Bernhisel (cadre), Lucien Woodworth (cadre), George Miller (cadre), Alexander Badlam (cadre), Peter Haws (cadre), Erastus Snow (cadre), Reynolds Cahoon (cadre), Amos Fielding (cadre), Alpheus Cutler (cadre), Levi Richards, Newel K. Whitney, Lorenzo D. Wasson (cadre), and William Clayton.

[52] JSP, CFM:40.

[53] JSP, CFM:48 (14 March 1844). See Clayton, journal, 1 January 1845, as quoted in Ehat, “Heaven Began on Earth,” 2; Andrus, Joseph Smith and World Government, 4; and Minutes of Council of Fifty, Saturday, 10 April 1880. The council was also referred to by other names, including “Special Council,” “General Council,” “Grand Council of the Kingdom of God,” and “The Fifties.” However, it was generally known as the Council of Fifty.

[54] The lone exception, Isaac Morley, entered the council the next year.

[55] JSP, CFM:44–45 (11 March 1844); and Nauvoo Diaries of William Clayton, 11 March 1844.

[56] Orson Pratt, “The Kingdom of God,” in JD, 3:73 (8 July 1855).

[57] JSH, F-1:18 (12 May 1844).

[58] JSP, CFM (18 April 1844):128; and Brigham Young, “The Kingdom of God,” in Journal of Discourses, 2:309–10 (8 July 1855).

[59] JSP, CFM:128 (18 April 1844).

[60] Taylor, Revelations, 1882–1883, MSS 1266, 17 June 1882.

[61] See Ehat, “Heaven Began on Earth,” 4.

[62] JSP, CFM:100, 101 (11 April 1844).

[63] Orson Hyde to Joseph Smith, 9 June 1844, p. 1; and Parley P. Pratt to Joseph Smith and Quorum of the Twelve, 19 April 1844, p. 2.

[64] George A. Smith, JSP, CFM:116 (18 April 1844).

[65] Lyman Wight and Heber C. Kimball to Joseph Smith, 19 June 1844.

[66] Orson Hyde to Joseph Smith, 9 June 1844.

[67] See Hyde, “Statement about Quorum of the Twelve.”

[68] Emphasis added.

[69] Some assert that this 26 March 1844 meeting was actually a 22 or 23 March meeting of the Anointed Quorum. However, no evidence points to women in attendance, which would have been the case with a meeting of the Anointed Quorum. Furthermore, in the meeting Joseph declared that several attendees needed the endowment before the temple’s completion, which would make no sense if this were an Anointed Quorum meeting, as by definition its members had already received their endowments (whereas 25 percent of the Council of Fifty were not endowed). Circumstantial evidence also points to this being a Council of Fifty meeting. During the succession crisis, some members of the Council of Fifty argued that the keys rested with them as well as with the Twelve.

[70] See Van Orden, “William W. Phelps’s Service in Nauvoo.” The multiple options being considered by Joseph fit his pattern of seeking revelation to guide the church by first following the counsel to “study it out in your mind” (Doctrine and Covenants 9:8). See also Andrus, Joseph Smith and World Government, 45–46.

[71] “Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons, 1 May 1844, 522–24.

[72] JSP, CFM:73 (26 March 1844).

[73] “Conference Minutes,” Times and Seasons, 15 July 1844, 578. In a Council of Fifty meeting the following week, Hyrum Smith would say, “We have greater power and are called to a greater work” than even that of Moses and Enoch. JSP, CFM:93 (11 April 1844).

[74] JSH, E-1:1957–58, 70–71 (7 April 1844); emphasis added.

[75] JSH, E-1:1982 (8 April 1844).

[76] JSH, E-1:1982 (8 April 1844).

[77] JSH, E-1:1993 (9 April 1844).

[78] General Church Minutes, 9 April 1844, 35.

[79] General Church Minutes, 8 April 1844, 32.

[80] JSH, E-1:1995–96 (9 April 1844).

[81] JSJ, 9 April 1844.

[82] General Church Minutes, 9 April 1844, 36.

[83] JSH, E-1:1998 (9 April 1844).

[84] JSP, CFM:103 (11 April 1844).

[85] History of the Church, 6:325. See also Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 165.

[86] JSJ, 9 April 1844. The minutes record the name of each volunteer and the state he was to labor in. Some names are underlined to indicate that they have not been assigned. Several assignments are crossed out and new ones recorded, corroborating that the names were read and corrected. The change in assignments was most likely from the church leaders. Joseph’s journal says 244 volunteered. However, in Thomas Bullock’s minutes, there are 277 names. Six are either crossed out or are repeats, leaving the number at 271. See “Minutes and Discourses, 6–9 April 1844,” pp. 37–39, https://

[87] JSH, E-1:2000 (9 April 1844).

[88] General Church Minutes, 9 April 1844, 35.