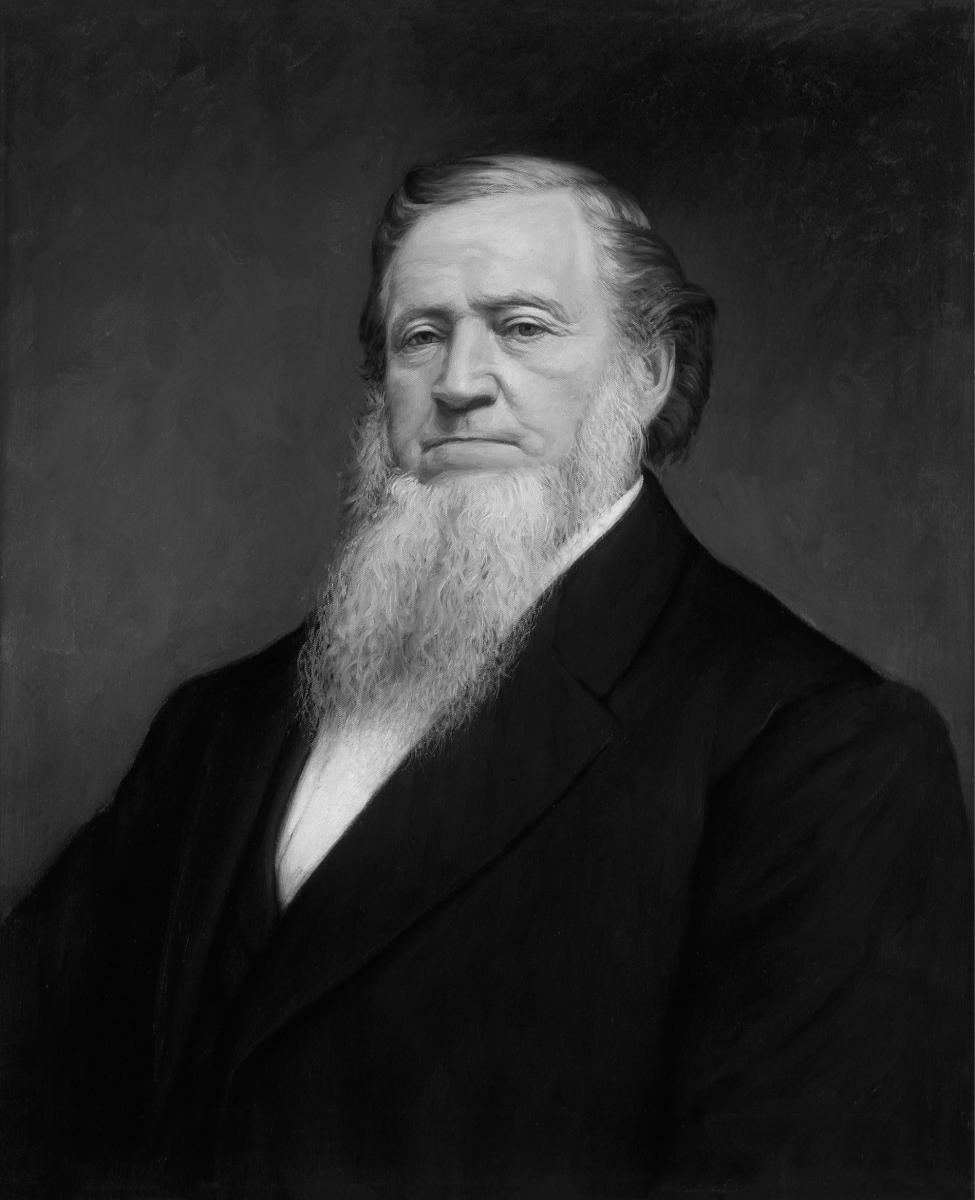

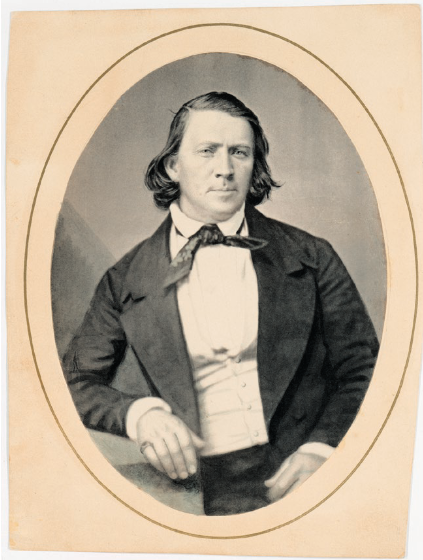

Chad M. Orton, "'This Shall Be Our Covenant': Brigahm Young and D&C 136," Religious Educator 19, no. 2 (2018): 119–51.

Chad M. Orton (ortoncm@ldschurch.org) was curator in the Historical Sites Division of the Church History Department and coauthor of 40 Ways to Look at Brigham Young: A New Approach to a Remarkable Man when this was written.

Brigham emphatically declared: "There is great delight in the law of the Lord to me, for the simple reason — it is pure, holy, just, and true...My religion is to know the will of God and do it."

Brigham emphatically declared: "There is great delight in the law of the Lord to me, for the simple reason — it is pure, holy, just, and true...My religion is to know the will of God and do it."

Two and one-half years after Brigham Young assumed the primary leadership role for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and nearly a year after the first Saints left Nauvoo, Illinois, to begin the journey west, the responsibility of leading the Church had taken a physical toll on him. By January 1847 he had lost so much weight that his clothes no longer fit. The reason was that the Latter-day Saints had literally and figuratively become stuck in the mud. Worn out and needing wisdom on how to extricate the Church and move the work forward, Brigham received the answers he desperately needed when the Lord revealed his “Word and Will,” a revelation later canonized as Doctrine and Covenants section 136.

Because this only canonized revelation of Brigham Young begins by addressing “the Camp of Israel in their journeyings to the west” (v. 1), it has been primarily viewed, and often glossed over, as simply a “how to” guide for organizing pioneer companies. While the revelation contains specific organizational concepts (v. 3, 5, 7, 15), organizing companies for emigration was only one aspect of its contribution towards advancing the work. More importantly, the revelation helped to refocus Brigham and the Saints on the importance of the covenants they had made and served as a reminder that both personal salvation and the progress of the Church were dependent upon harkening to the word of Lord.[1]

Received at a pivotal time in the history of the Church, the “Word and Will of the Lord” became a seminal moment for Brigham and provided him an important “before and after” lesson. The “before” was the 1846 journey across Iowa; the “after” was the 1847 travels of the vanguard pioneer company from Winter Quarters to the Salt Lake Valley.[2] Having proven the word of the Lord during the 1847 exodus, he subsequently included the revelation’s principles in his teaching as he continued to lead the Saints after they had reached their promised land.[3] Thus, while section 136 had a great effect upon Brigham as “American Moses” in gathering the Saints, it also had an influence on him in his role as “American Joshua” overseeing Mormon settlement of the West.

The Before: Iowa, 1846

When Brigham made the decision for the Saints to begin leaving Nauvoo in February 1846’s bitter cold, he fully expected to lead the vanguard company of approximately three hundred men to their new home that year.[4] His goal was to arrive early enough to grow crops that would help sustain the thousands of Latter-day Saints who would subsequently join them before the year was out. Instead of reaching the Rocky Mountains, however, his company struggled to make it across Iowa. Rather than taking four to five weeks to reach the Missouri River as anticipated, that portion of the journey had taken more than four months. The delay in part was the result of heavy rains that caused streams and rivers to rise significantly above normal levels and turned rolling plains into muddy quagmires.

Iowa’s mud and swollen rivers would have been less problematic if the advance company had not been joined by more than a thousand others, an unwieldy number that further slowed its progress. Many of these Saints had left Nauvoo ahead of schedule because of fears regarding the Church’s enemies, while others were simply anxious to get on the road or to travel with Brigham and other members of the Twelve in a time of uncertainty. Having left earlier than planned, a large number were ill-prepared for the journey. Helen Mar Kimball Whitney recalled, “There was such a great desire among the people and such a determination to emigrate with the first company that there [were] hundreds [who] started without the necessary outfit.”[5] The situation prompted a frustrated Brigham to declare three months into the journey: “The Saints have crowded on us all the while, and have completely tied our hands by importuning and saying do not leave us behind. Wherever you go we want to go and be with you, and thus our hands and feet have been bound which has caused our delay.”[6]

Winter Quarters, 1846–47

When the advance company finally reached the Missouri River in mid-June 1846, their energy and supplies were largely spent. As a result, they were forced to find a place to winter and try again the following year.

In addition to these pioneers, thousands of other Latter-day Saints had left Nauvoo as scheduled, expecting their journey would end that year in the place which God had prepared for them “far away in the west.”[7] Instead, they also needed a temporary home. By the fall of 1846, more than 7,000 were in exile near the Missouri River, living in caves, wagons, makeshift hovels and log cabins, primarily at Winter Quarters, Nebraska, and Kanesville, Iowa. Another 3,000 were forced to winter under similar conditions at settlements further back along the trail. At these various locations, many were sick or dying from malnutrition and exposure, and a number were experiencing a crisis of faith.

Not only had the delays and the resulting disappointment of not reaching the promised land taken a physical and emotional toll on Brigham, but to this was added the stress and toil of having to prepare for the upcoming emigration season while at the same time having to see to it that the needs of the Saints were met. Shortly before the “Word and Will” was received it was reported that Brigham slept “with one eye open and one foot out of bed, and when anything is wanted, he is on hand.”[8] Not surprisingly, all of this made Winter Quarters among the most difficult periods of his life. He wrote at the time that he felt “like a father with a great family of children around me” and later recalled that his responsibilities pressed down upon him like a “twenty-five ton weight.”[9] The task that he had been given was beyond his natural ability and he needed assistance if he was to accomplish the work.

“Word and Will of the Lord” Is Received

Although the Iowa experience and the stress of Winter Quarters weakened Brigham physically, they helped prepare him to receive the “Word and Will of the Lord” at a time when it would be both welcomed and fully embraced.[10] On January 14, 1847, after months of contemplation, councils, and prayer, Brigham received the help he anxiously sought to move the work forward.[11] Two days later the revelation was presented to the Saints at Winter Quarters.

While most principles of the revelation had been previously revealed to Joseph Smith or could be found in ancient scripture, the Saints had not always acted as if they were important. Now, however, they found a ready place in Brigham’s heart. As Brigham’s subsequent actions demonstrated, the message he took away from this revelation was straight forward. Modern Israel, like ancient Israel, had become “lost” in the wilderness because they had not always harkened to the voice of the Lord. Brigham and the Saints had been doing things their way and hadn’t made as much progress as they had hoped. Now it was time to try it the Lord’s way.[12]

In addition to providing Brigham the answers he needed to put the Church back on track, the revelation served as a powerful witness to Brigham and the Saints that because they were on the Lord’s errand, the Lord did not expect them to carry out his work without his help. In presenting the revelation to the Saints, Brigham emphatically reassured them that the Church continued to be “led by Revelation just as much since the death of Joseph Smith as before.”[13]

Implementing the “Word and Will”

As instructed in the revelation (vv. 3, 15), beginning in 1847 Brigham placed a renewed emphasis upon organizing emigrating companies with “captains of hundreds, captains of fifties, and captains of tens, with a president and his two counselors at their head.”[14] Brigham had attempted to organize the Saints in a similar manner prior to their leaving Nauvoo, but the organizational structure had not always been viewed as essential. Now in 1847 the way the Saints were organized would become so important that even before Brigham began dictating the revelation he directed “that letters be written to instruct the brethren how to organize companies for emigration.”[15]

The revelation’s organizational pattern was not new. Moses, at the suggestion of his father-in-law and with the blessing of the Lord, first employed it during the Exodus. Jethro, seeing the toll that the journey was taking upon his son-in-law, encouraged Moses to appoint “rulers of thousands, and rulers of hundreds, rulers of fifties, and rulers of tens,” “able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness.” Jethro envisioned these individuals serving as the leaders and judges over their respective groups, taking to Moses only the “great matter[s]” they could not resolve. Jethro told Moses that this organizational model would make the journey “easier” on him since these rulers could “bear the burden with” him. Jethro encouraged Moses to take this pattern to the Lord to see if “God command thee so,” noting that if he did command it, “then thou shalt be able to endure, and all this people shall also go to their place in peace.”[16]

Joseph Smith had used a similar pattern in organizing “Zion’s Camp” in 1834, calling the leaders “captains” rather than “rulers.”[17] The model was also employed on a limited basis during the Mormon exodus from Missouri during the winter of 1838–39, although most of those fleeing the state traveled as families or in small groups they organized themselves.

In addition to giving a renewed emphasis to this aspect of company organization, Brigham also implemented two other organizational changes. First, the size of a company would be limited to no more than 100 wagons. Secondly, once individuals became members of a specific company, they were to remain part of that company throughout the journey, except in unusual circumstances. This policy of having membership in one company was a marked departure from the fluidity of company membership that was an aspect of the exodus across Iowa and that would continue to be a common practice among non-LDS emigrants.[18] Although the ideal was not always realized, beginning in 1847 the Mormon exodus became “the most carefully orchestrated, deliberately planned, and abundantly organized hegira in all of American history.”[19]

At the same time that he was making preparations for the 1847 emigration, Brigham embraced the Lord’s injunction that when “companies are organized let them go to with their might, to prepare for those who are to tarry,” by preparing “houses, and fields for raising grain” (vv. 6, 9). In connection with the Twelve, he sent out instructions that all who remained behind needed to be “amply provided for,” declaring that “those who are going to remove this spring” had the responsibility to “use all diligence in plowing, planting, sowing and building for those who are to remain.”[20]

In addition to designating the land that was to be used for the planting and sowing when conditions that spring would allow, he “counseled the brethren to get timber and season it” in the meantime so that there would be lumber available in 1848 to build wagons for that year’s emigration.[21] Because Winter Quarters had been established on the edge of “Indian land,” he set in motion plans for the creation of a stockade where individuals could obtain safety in the event of an attack.[22] Shortly before the vanguard company left, he also requested “those who were ready to start to assist in removing some families” to better living quarters.[23]

In addition to overseeing the general needs of the Saints, Brigham also focused attention upon the families of the members of the vanguard company. He met “with the brethren of the Twelve, the presidents of companies and captains” and outlined “the policy to be pursued by the Pioneers in leaving their families.”[24] One aspect of this policy stipulated that no one would be allowed to go west unless each “individual in his family” had “300 lbs of bread stuff” to live on.[25]

The Twelve to Teach the Lord’s Will to the Saints

As important as was the instruction as to how the exodus was to be organized was the Lord’s declaration as to who was to lead the Saints. The “Word and Will of the Lord” proclaimed that the journey, and thus the future of the Church, was “under the direction of the Twelve Apostles” (v. 3).[26] Because the revelation served as a testament that the Twelve were the authorized successors to Joseph Smith until the First Presidency was reorganized, Hosea Stout concluded that it would “put to silence the wild bickering and suggestions of those who are ever in the way. . . . They will now have to come to this standard or come out in open rebellion to the Will of the Lord.”[27]

The revelation (D&C 136) served as a powerful witness to Brigham Young and the Saints that because they were on the Lord’s errand, the Lord did not expect them to carry out his work without his help.

The revelation (D&C 136) served as a powerful witness to Brigham Young and the Saints that because they were on the Lord’s errand, the Lord did not expect them to carry out his work without his help.

Of the six individuals specifically commanded in the revelation to organize companies (vv. 12–14), five were members of the Twelve (Ezra T. Benson, Orson Pratt, Wilford Woodruff, Amasa Lyman and George A. Smith), while the sixth, Erastus Snow, would fill a vacancy in the Quorum in 1849. None of those individuals, however, would travel with the companies they organized. Instead, each was a member of the first pioneer company to enter the Salt Lake Valley.[28] By employing the revelation’s organizational pattern, Brigham and the Twelve were now freed up to lead out and provide general leadership for the Church since the day-to-day responsibility for each company of Saints now resided with its presidency and captains.

As significant as was the Lord’s testimony of the Twelve was his declaration that they had the collective responsibility to “teach this, my will, to the saints” (v. 16). The fact that the Church was organized according to the word of the Lord little mattered if the Saints’ behavior also did not collectively reflect the will of the Lord.[29] In this regard the revelation served as a forceful reminder to Brigham that he and other members of the Twelve had a similar charge to that given to Moses—they were to teach the “ordinances and laws” and to show the Saints “the way wherein they must walk, and the work that they must do.”[30]

Immediately Brigham went to work to ensure that members of the Twelve fully understood what the Lord expected of both them and the Latter-day Saints. While a number of Saints had willfully ignored counsel during the previous year’s journey, there was also a large number who had not been sufficiently taught what was expected of them, a situation that the Twelve were now charged to rectify. Brigham also informed Church members that the Twelve would “communicate with, instruct, and counsel you as they shall be directed by the Holy Spirit, and we call upon you to give heed to their admonitions in all things, which if you do, ye shall find peace and rest, and safety and prosperity.”[31]

Establishing the Trail along the Covenant Path

Central to the revelation was the reminder that modern Israel was a covenant people and that covenants were an essential aspect of the Lord’s work. In verse 2 the Lord declared that the Latter-day Saints were to undertake their exodus “with a covenant and promise to keep all the commandments and statues of the Lord our God.” In verse 4 the “Word and Will” further stated that “this shall be our covenant—that we will walk in all the ordinances of the Lord.”

Prior to leaving Nauvoo, Brigham had written that the most important thing “for the salvation of the Church” was for the Latter-day Saints to reach their promised land.[32] Following the revelation, his declarations stressed that behavior was more essential to the salvation and destiny of the Church and its members than physical location.[33] He would emphasize to the vanguard company that their responsibility extended beyond just blazing a trail that others would follow in the coming months and years. They also had a duty to see that the trail was established along the Lord’s covenant path and in harmony with the revealed word of the Lord.[34]

Besides their baptismal covenants, many Latter-day Saints had made temple covenants in the months leading up to the exodus from Nauvoo. During that time, Brigham oversaw a concerted effort to ensure that as many Saints as possible received their endowments and participated in other sacred ordinances in the Nauvoo Temple before heading into the wilderness.[35] Section 136 served as a reminder that while it was important to make covenants, it was equally as important to strive to keep them.[36]

The “Word and Will of the Lord” also emphatically reminded the Saints that their ultimate success was dependent upon God: “I am he who led the children of Israel out of the land of Egypt; and my arm is stretched out in the last days, to save my people Israel” (v. 22). Besides making a direct tie between the exoduses of modern and ancient Israel, the revelation indirectly provided the Latter-day Saints a connection to the journey of Lehi and Nephi, during which the Lord declared: “Inasmuch as ye shall keep my commandments, ye shall prosper, and shall be lead to a land of promise. . . . I will prepare the way before you, if it so be that he shall keep my commandments; wherefore, inasmuch as ye shall keep my commandments ye shall be led towards the promised land; and ye shall know that it is by me that ye are led. . . . After ye have arrived in the promised land, ye shall know that I, the Lord, am God; and that I, the Lord, did deliver you.”[37]

Although section 136’s reference to ordinances, covenants and obedience brought new hope, it also served as a warning. After the Saints failed to redeem Zion in 1834, the Lord admonished the Saints: “Were it not for the transgressions of my people, speaking concerning the church and not individuals, they might have been redeemed even now. But behold, they have not learned to be obedient to the things which I require at their hands.”[38] The lessons of the past were not lost on Brigham in 1847.

With a new understanding came a new attitude and a renewed energy. As God’s people, they not only had the responsibility to undertake the journey in a different manner, they also had the privilege. The ultimate success of the Saints settling their promised land was now less dependent upon maps, wagons and supplies than upon aligning their efforts with the word and will of the Lord. If they were to accomplish the task before them, spiritual preparation was more important than physical preparation and personal behavior than personal property.

While Brigham may have had concerns during his travels across Iowa as to how the Saints would succeed, he was certain during the journey from Winter Quarters that if the Saints were endeavoring to keep their covenants and live according to the revealed word they couldn’t fail, even if they again encountered circumstances beyond their control. Believing that they could bind the Lord to help them because of their faithfulness, Brigham “warned all who intended to proceed to the mountains that iniquity would not be tolerated in the Camp of Israel.” He also declared that he “did not want any to join [the vanguard] company unless they would obey the word and will of the Lord, live in honesty and assist to build up the kingdom of God.”[39] Only after individuals had been taught what was expected of them and agreed to live according to the revealed word were they permitted to add their names to the list of those who could emigrate.

Although a shortage of food had been a major issue during the Saints’ journey across Iowa, after the revelation Brigham believed that food and supplies need not be a primary concern if the Saints were striving to fulfill their part of their covenants. Four days after receiving section 136, he publicly proclaimed that he “had not cattle sufficient to go to the mountains” but that he “had no more doubts nor fears of going to the mountains, and felt as much security as if [he] possessed the treasures of the East.”[40] He further stated that each member of the vanguard company only needed to take one hundred pounds of food with them on their journey into the wilderness, declaring that all “who had not faith to start with that amount” could stay at Winter Quarters.[41]

A month into the journey, Brigham responded to the fears of some that the company might not reach their destination in time to plant crops: “Well, suppose we [do] not. We [have] done all we could & travelled as fast as our Teams were able to go.” He reassured the company that if they had done their part he would feel “as well satisfied as if we had a thousand acres planted with grain. The Lord would do the rest.”[42] Convinced that the Lord was as capable of making it rain manna on the plains of North America as on the plains of Arabia, Brigham’s testimony echoed the words of the Prophet Isaiah: “I never felt clearer in mind than on this journey. My peace is like a river between my God and myself.”[43]

Even the number of men making up the 1847 vanguard company may be evidence of this new attitude. Rather than 300 men, the number was halved to 144.[44] While there is no contemporary account as to why that specific number, a popular but unsupported belief has arisen that it reflected the twelve tribes of Israel.[45]

The After: Winter Quarters to the Salt Lake Valley, 1847

What is certain is that there was a noticeable change among the Saints following the revelation. William Clayton observed: “It truly seemed as though the cloud had burst and we had emerged into a new element, a new atmosphere, and a new society.”[46] The experiences at Winter Quarters, coupled with the subsequent journey to the Salt Lake Valley, became a teaching moment for the Twelve in terms of leading the Church, and for the Latter-day Saints generally in giving heed to the will of the Lord. George A. Smith declared that the Saints would look back at their journey as “one of the greatest schools they ever were in,” while Wilford Woodruff wrote, “we are now in a place where we are proving ourselves.”[47] In addition to proving the faith and obedience of Brigham and the Saints, the journey would become an exercise in proving the word of the Lord.

In spite of the Saints’ new commitment, the 1847 exodus was not without its trials. The vanguard company repeatedly found their resolve and faith tried. The initial plan was to leave “one month before grass grows,” but no later than March 15. However, spring was late in coming and the early grass grew weeks later than anticipated. Because of the unseasonably cold weather, the company was unable to get underway from its rendezvous location until mid-April.[48] The excitement of finally beginning the journey was soon tempered by the realities of unseasonably cold nights, windswept prairies, challenging river crossings, the loss of stock, and days filled with long, monotonous travel.

While there was an overall reformation in conduct among the members of the vanguard company, at times Brigham, having become passionately committed to the principles of the revelation, found himself frustrated with the behavior of some company members. In late May he read “the Word and Will of the Lord” to the company and “expressed his views and feelings . . . that they were forgetting their mission.” He further proclaimed that he would “rather travel with 10 righteous men who would keep the commandments of God than the whole camp while in a careless manner and forgetting God.”[49] The following day he declared that he wanted the company “to covenant to turn to the Lord with all their hearts. . . . I have said many things to the brethren about the strictness of their walk and conduct when we left the gentiles, and told them that we would have to walk upright or the law would be put in force. . . . If we don’t repent and quit our wickedness we will have more hindrances than we have had, and worse storms to encounter.” Having reproved with sharpness, Brigham then “very tenderly blessed the brethren and prayed that God would enable them to fulfill their covenants.”[50]

Ultimately, the 1847 emigration stood in dramatic contrast to the previous year’s journey. While Brigham Young’s company had traveled around 300 miles in 1846, in 1847 the vanguard pioneer company traveled approximately 1,000 miles in a shorter amount of time. Brigham attributed the difference to the Lord keeping his promise to lead and bless the Saints because of their efforts to align their will with his.

“The Word and Will”: The Practical Approach

After a brief stay in the Salt Lake Valley, Brigham returned to Winter Quarters in the fall of 1847. During the return trip he encountered the companies that Church leaders had organized according to the revelation. Instead of these companies traveling according to the “Word and Will of the Lord” and subsequent decisions of the Twelve, they had essentially become one large company consisting of nearly 1,500 individuals and 600 wagons.[51] There had been many problems along the way, including company members contending over the best camping spots.

More disconcerting to Brigham was the fact that this large company included two members of the Twelve—Parley P. Pratt and John Taylor. Both of these individuals had chosen not to travel with the vanguard company and the rest of the Twelve because they had just returned from missions to England and wanted more time before they undertook the westward journey. Although neither had been at Winter Quarter’s when section 136 was received and began to be implemented, Brigham had seen to it that they were taught about the revelation and informed about the decisions of the Twelve.

However, when Pratt and Taylor were preparing to leave the rendezvous location in mid-June, they concluded they would have to set aside the revelation and the decisions of the Twelve if they were to reach the valley that fall. “Theory is not what we will see now so much as the practical,” Pratt declared at the time.[52] For Brigham, the word of the Lord was not theory—it was the practical approach. When Brigham discovered what had happened and why, he could not hide his frustration with Pratt and Taylor: “Our companies were perfectly organized . . . Why should our whole winter’s work be set at naught[?] . . . If the Quorum of the Twelve does a thing it is not in the power of two of them to rip it up. . . . I know you have had a hard time and you have brought it on yourself. . . . We’ve got the machine a moving[;] it is not your business to stick your hands among the cogs and stop the wheel.”[53] In essence, Brigham reminded them what he had previously publicly declared: “When God tells a man what to do, he admits of no argument, and I want no arguments.”[54] Both Pratt and Taylor accepted the reproof and acknowledged their mistake.[55]

“The Word and Will”: Personal Anchor Points

Having proven for himself how the Saints were better off heeding the word and will of the Lord, Brigham never forgot the lessons he learned as a result of having received and implemented section 136. His focus upon the benefits of covenants and the importance of hearkening to the revealed word of the Lord caused the anxiety he felt at Winter Quarters to fade away. He subsequently found himself “full of peace by day and by night,” and sleeping as “soundly as a healthy child in the lap of its mother.”[56]

Near the end of his life Brigham emphatically declared: “There is great delight in the law of the Lord to me, for the simple reason—it is pure, holy, just, and true. . . . My religion is to know the will of God and do it.”[57] Not only had section 136’s general principles become personal anchor points for him, but during the thirty years that he led the Church he faithfully taught the Saints through word and deed the importance of making them, along with other aspects of the revealed word of the Lord, anchor points in their own lives as well.

“Bear an Equal Proportion”

In verses 8 and 10, the “Word and Will of the Lord” declared that the Saints had the responsibility to “bear an equal proportion, according to the dividend of their property, in taking the poor, the widows, the fatherless, and the families of those who have gone into the army [Mormon Battalion], that the cries of the widow and fatherless come not up into the ears of the Lord against this people. . . . Let every man use all his influence and property to remove this people.”[58] Prior to leaving Nauvoo, Brigham had moved at October 1845 conference “that we take all the saints with us, to the extent of our ability, that is, our influence and property.” Only 214 individuals, however, signed the “Nauvoo Covenant”—a number insufficient to meet the needs of all who wanted to start west.[59] As a result, in the fall of 1846 several hundred Latter-day Saints who had remained behind because of poverty and sickness were driven from Nauvoo by armed mobs, most unprepared for the journey.

Following the revelation, Brigham put a renewed emphasis upon the Saints’ collective responsibility to assist those who needed help emigrating. As soon as companies were organized for the 1847 emigration, he instructed the captains of ten “to ascertain what property their ten possessed, so that the widows and women whose husbands were in the army might be taken along, so far as there was means to take them.”[60] He and other members of the Twelve also instructed the Saints that “the widow and the fatherless must not be forgotten, let as many of them be taken as can.” They further noted that they wanted each company “to take as many of the sisters whose husbands . . . are in the army, so that when we meet the Battalion, they will bless us, greet their families with thanksgiving, and immediately go to planting, plowing and sowing, instead of being obliged to walk back some hundreds of miles further, after their long and tedious journey and wasting their flesh, and blood, and bones to no purpose.”[61]

Part of Brigham’s frustration with Pratt and Taylor centered on the fact that they had not brought with them as many of these individuals as anticipated, in spite of the Lord’s promise that if the Saints would “do this with a pure heart, in all faithfulness, ye shall be blessed; you shall be blessed in your flocks, and in your herds, and in your fields, and in your houses, and in your families” (v. 11). As a result of the decision to ignore this aspect of the revelation, more than thirty Mormon Battalion members upon arriving at Salt Lake and discovering their families had been left behind, immediately undertook the long journey back to the Missouri River in the fall of 1847.

Once settled in Utah, Brigham through word and deed continued to emphasize the need for the Saints to help the poor and widows. “The Latter-day Saints . . . have got to learn that the interest of their brethren is their own interest, or they never can be saved in the celestial kingdom of God,” he declared.[62] On another occasion he proclaimed: “The Lord will bless that people that is full of charity, kindness and good works. When our monthly fast days come round, do we think of the poor? If we do, we should send in our mite, no matter what it is. . . . If God has not sustained us after all that we have passed through, let some one tell how we have been sustained.”[63]

In addition to using his own resources to help gather individuals and support them once they had arrived in Utah, Brigham introduced specific programs such as the Perpetual Emigrating Fund, and the use of handcarts and down-and-back companies, thus allowing individuals to gather who lacked sufficient means to purchase a wagon and team. He also tried to keep the concept of pure religion before the Saints by organizing United Orders, and attempting to implement the Law of Consecration.

“In Mine Own Due Time”

In the revelation the Lord declared that “Zion shall be redeemed in mine own due time” (v. 18). Because Brigham had been so anxious to reach the Saints’ promised land in 1846, he had not fully embraced what Joseph Smith had told him in a dream he had during the whirl of activities leading up to the exodus from Nauvoo: “Brother Brigham don’t be in a hurry—this was repeated the second and third time, when it came with a degree of sharpness.”[64] To ancient Israel, the Lord had made a similar declaration: “For ye shall not go out with haste, nor go by flight: for the Lord will go before you; and the God of Israel shall be your rearward.”[65]

Having learned his lesson during the 1846 and 1847 westward journeys, Brigham counseled those who would be returning to Winter Quarters in the fall of 1847 to “not give way to an over anxious Spirit so that your Spirits arrive at Winter Quarters before the time that your bodies can possibly arrive there.”[66] He later encouraged all the Saints to slow down and make certain they were putting the Lord first: “You are in too much of a hurry. You do not go to meeting enough, you do not pray enough, you do not read the Scriptures enough, you do not meditate enough, you are all the time on the wing, and in such a hurry that you do not know what to do first.” He concluded that many listening to him likely had not prayed that morning, their reason being that they had too much to do. “Stop! Wait!” he pled. “When you get up in the morning, before you suffer yourselves to eat one mouthful of food, . . . bow down before the Lord, ask him to forgive your sins, and protect you through the day, to preserve you from temptation and all evil, to guide your steps aright, that you may do something that day that shall be beneficial to the kingdom of God on the earth. Have you time to do this? Elders, sisters, have you time to pray? This is the counsel I have for the Latter-day Saints to-day. Stop, do not be in a hurry.”[67]

“Let Him That Is Ignorant Learn Wisdom”

The revelation also warned against pride and the attitude of some individuals that they really weren’t dependent upon the Lord: “And if any shall seek to build up himself, and seeketh not my counsel, he shall have no power, and his folly shall be made manifest. . . . Let him that is ignorant learn wisdom by humbling himself and calling upon the Lord his God, that his eyes may be opened that he may see, and his ears opened that he may hear; For my Spirit is sent forth into the world to enlighten the humble and contrite, and to the condemnation of the ungodly” (v. 19, 32–33).

Shortly after Brigham received the “Word and Will of the Lord,” Joseph Smith again appeared to him in a dream. In response to Brigham’s request for advice, Joseph declared: “Tell the people to be humble and faithful, and be sure to keep the spirit of the Lord and it will lead them right. Be careful and do not turn away the small still voice; it will teach them what to do and where to go; it will yield the fruits of the kingdom. Tell the brethren to keep their hearts open to conviction, so that when the Holy Ghost comes to them, their hearts will be ready to receive it.” Joseph further noted that the Saints “can tell the Spirit of the Lord from all other spirits; it will take malice, hatred, strife and all evil from their hearts; and their whole desire will be to do good, bring forth righteousness and build up the kingdom of God. Tell the brethren if they will follow the Spirit of the Lord, they will go right.”[68]

Like Joseph Smith, Brigham was uneducated by the standards of the day. Also like Joseph, Brigham readily acknowledged that his accomplishments, including leading the Saints to their promised land, were not the result of his natural talents and abilities as a leader but because he was a devoted follower: “What I know . . . I have received from the heavens, . . . not alone through my natural ability, and I give God the glory and the praise. Men talk about what has been accomplished under my direction, and attribute it to my wisdom and ability; but it is all by the power of God, and by intelligence received from him.”[69] On another occasion he stated: “What do you suppose I think when I hear people say, ‘O, see what the Mormons have done in the mountains. It is Brigham Young. What a head he has got!’ . . . It is the Lord that has done this. It is not any one man or set of men; only as we are led and guided by the spirit.”[70]

Near the end of Brigham’s life, a visitor to the Beehive House, Brigham’s home in Salt Lake City, commented on a painting of the Prophet Joseph hanging on the wall, observing that it “did not show any great amount of strength, intelligence, or culture.” In response Brigham acknowledged that Joseph Smith “was not a man of education, but received such enlightenment from the Holy Spirit that he needed nothing more to fit him for his work as a leader.” Brigham then added, “And this is my own case also. . . . All that I have acquired is by my own exertions and by the grace of God, who sometimes chooses the weak things of earth to manifest His glory.”[71]

Brigham warned the Saints: “If you do not open your hearts so that the Spirit of God can enter your hearts and teach you the right way, I know that you are a ruined people.”[72] On another occasion he stated: “I think there is more responsibility on myself than any other one man on this earth pertaining to the salvation of the human family; yet my path is a pleasant path to walk. . . . All I have to do is to live . . . [so as to] keep my spirit, feelings and conscience like a sheet of blank paper, and let the Spirit and power of God write upon it what he pleases. When he writes, I will read; but if I read before he writes, I am very likely to be wrong.”[73]

Brigham also decried the fact that there were individuals in the Church who had too high opinions of themselves, observing on one occasion: “I have seen men who belonged to this kingdom, and who really thought that if they were not associated with it, it could not progress.”[74] On another occasion he declared, “Never ask how big we are, or inquire who we are.” Instead, he wanted individuals to ask, “What can I do to build up the kingdom of God upon the earth?”[75]

Because his desire was to build the kingdom, in addition to seeking to know the Lord’s will, Brigham was not above doing the small things. He willingly undertook tasks that many leaders left to others. When a ferry was needed during the 1847 journey, he “went to work with all his strength” and assisted in making “a first rate White Pine and white Cotton Wood Raft.”[76] The following year on his second journey to Utah, he crossed and re-crossed the North Platte River assisting company members safely across.[77]

During the early days in the valley, Brigham spent time physically assisting Saints by chopping wood, building houses, etc., often at the expense of other duties. On one occasion when Jedediah M. Grant sought out Brigham on a public matter, Grant found him shingling a roof. Frustrated, Grant told him: "Now, Brother Brigham, don't you think it is time you quit pounding nails and spending your time in work like this? We have many carpenters but only one Governor and one President of the Church. The people need you more than they need a good carpenter.”[78] Reluctantly Brigham came down from the roof to fulfill the roles that were his alone.

While Brigham would give his ecclesiastical and civic duties their proper attention, he also continued to do the little things. On one occasion a stranger approached Brigham while he was on the steps of his carriage loading luggage for a journey. “Is Governor Young in this carriage?” the man asked. “No, sir,” Brigham replied, “but he is on the steps of it.”[79] Elizabeth Kane reported that during a journey she and her husband Thomas L. Kane made through Utah with Brigham in 1872 that he personally inspected “every wheel, axle, horse and mule, and suit of harness belonging to the party” to make sure they were in good condition.[80]

He also did not take himself too seriously. During a visit to the home of Anson Call, Brigham took one of Call’s young daughters on his knee and as he started to tell her how pretty she was the child blurted out, “Your eyes look just like our sow’s!” To this Brigham replied: “Take me to the pig pen. I want to see this pig that has eyes just like mine.’” When the story was later retold, Brigham laughed as much as anyone.[81]

One contemporary critic of Brigham acknowledged that “the whole secret” of his “influence lies in his real sincerity. . . . For the sake of his religion, he has over and over again left his family, confronted the world, endured hunger, come back poor, made wealth and given it to the Church. . . . No holiday friend nor summer prophet, he has shared their trials as well as their prosperity.”[82] Because Brigham did not view himself as greater than his calling or above the work that the Saints had been asked to do, it is not surprising that those who knew him best lovingly referred to him as “Brother Brigham.”

“Keep All Your Pledges”

In verses 20, 25–26, the “Word and Will of the Lord” stressed the need for the Saints to adhere to the Judeo-Christian values of dealing honestly with their fellow men: “Keep all your pledges one with another; and covet not that which is thy brother’s. . . . If thou borrowest of thy neighbor, thou shalt restore that which thou hast borrowed; and if thou canst not repay then go straightway and tell thy neighbor, lest he condemn thee. If thou shalt find that which thy neighbor has lost, thou shalt make diligent search till thou shalt deliver it to him again.” Brigham taught the Saints, “Honest hearts produce honest actions—holy desires produce corresponding outward works.”[83] He also declared, “I have no fellowship for a man that will make a promise and not fulfil it.”[84]

When Brigham learned in 1866 that a note for a debt he incurred around 1826 while living in Auburn, New York, had been found, he asked his son, John W., who was bound for a mission to Europe, to make a side trip to Auburn, and cancel the debt: “A man by the name of Richard Steele kept a drug store about forty years ago. . . . He had my note for three dollars ($3.00), which I wished to take up, but he could not find it, and said that I must be mistaken about it. I offered to pay the amount, but he refused to receive it.” Brigham told his son that while Steele “may be dead . . . his heir or heirs may be living” and they were entitled to the money. In addition to paying the amount owed, Brigham instructed John W. to also pay forty year’s interest.[85]

“Thou Art His Steward”

Section 136 proclaimed: “Thou shalt be diligent in preserving what thou hast, that thou mayest be a wise steward; for it is the free gift of the Lord thy God, and thou art his steward” (v. 27). By word and deed Brigham directed the Saints’ attention to their responsibility to both beautify and protect the earth. “Not one particle of all that comprises this vast creation of God is our own,” he declared.[86] “How long have we got to live before we find out that we have nothing to consecrate to the Lord—that all belongs to the Father in heaven; that these mountains are His; the valleys, the timber, the water, the soil; in fine, the earth and its fullness.”[87]

Because of the interdependence between the temporal and spiritual, Brigham taught that the misuse of the earth’s resources was part of the ongoing battle between good and evil: “The enemy and opposer of Jesus . . . Satan, never owned the earth; he never made a particle of it; his labor is not to create, but to destroy; while, on the other hand, the labor of the Son of God is to create, preserve, purify, build up, and exalt all things—the earth and its fullness—to his standard of greatness and perfection; to restore all things to their paradisiacal state and make them glorious. The work of the one is to preserve and sanctify, the work of the other is to waste away, deface and destroy.”[88]

In 1847 Brigham reminded the vanguard pioneer company of Joseph Smith’s “instructions—given both on Zion’s Camp and by revelation—not to kill any of the animals or birds, or any thing created by Almighty God that had life, for the [mere] sake of destroying it.”[89] Two weeks later when men began to indiscriminately shoot buffalo, a frustrated Brigham declared that “it was a sin to waste life and flesh.”[90] He believed that God had not given mankind the right to selfishly and wastefully exploit the earth or to needlessly destroy his creations. Brigham’s belief stood in sharp contrast to what one European visitor observed in other areas of the American West. “Nothing on the face of the broad Earth is sacred to [the frontiersman],” this visitor wrote. “Nature presents herself as his slave” and man treats the world around him in a “shockingly irreverent manner.”[91]

During Mark Twain’s visit to California in 1861 he spent four hours in a canoe on Lake Tahoe watching a forest fire that he had accidently started. “It was wonderful to see with what fierce speed the tall sheet of flame traveled!” he gushed. After it was safe to return to shore, Twain felt a pang of regret—not for the destruction he had caused, but because his actions had caused him to miss dinner.[92] By contrast, following the 1860 Twenty-fourth of July celebration in Big Cottonwood Canyon, an eastern newspaper reporter was surprised to see that Brigham remained behind “after everyone was gone” and went to each campfire to “see that all fires were extinguished.”[93]

A long-term effect of Brigham as a steward of the Lord is City Creek Canyon, one of Salt Lake City’s natural treasures. Recognizing that City Creek was “the primary source of life-sustaining water” for the city, and wanting to show the “community a plan” for taking care of the Canyon, he took the extraordinary step in 1850 of petitioning the legislature “to grant unto him the exclusive control” over the canyon to ensure “that the water may be continued pure unto the inhabitants of Great Salt Lake City.”[94] He did this because of concerns about individuals who “lay down their religion at the mouth of the kanyon, saying, ‘thou lie there, until I go for my load of wood.’”[95] In 1853, after having built a road into City Creek and implementing a plan for the use of the canyon, Brigham allowed city residents back into the canyon.

Thirteen years after Brigham appropriated City Creek for the purpose of preserving it, Fitz Hugh Ludlow visited Salt Lake City. Like others, he noted the famous open streams that ran along the street. He was taken back, however, by the fact that the “inhabitants of Salt Lake City” drew a “supply of water for all purposes” from these streams. Ludlow noted: “All the earlier association of an Eastern man connect the gutter with ideas of sewerage; and a day or two must pass before he can accustom himself to the sight of his waiter dipping up from the street the pitcher of drink water for which he has rung, or the pail full which is going into the kitchen to boil his dinner. . . . Dead leaves and sand, the same foreign matters as the wind drifts into any forest spring, are necessarily found in such an open conduit; but no garbage, nothing offensive of any kind, disturbs its purity.” Unaware that these streams were being watched over by a faithful steward who had received his errand from the Lord, Ludlow marveled that “the water seems to take care of itself.” [96]

“Praise the Lord”

In verse 28, the “Word and Will” declared, “If thou art merry, praise the Lord with singing, with music, with dancing, and with a prayer of praise and thanksgiving.” Because many religionists felt that music and dancing were largely inconsistent with a Christ-centered life, Brigham grew up in a household that viewed them as sins. He later informed the Saints: “I had not a chance to dance when I was young, and never heard the enchanting tones of the violin, until I was eleven years of age; and then I thought I was on the high way to hell, if I suffered myself to linger and listen to it.”[97] However, before leaving Winter Quarters, Brigham became a proponent of these activities. Within days of receiving section 136, Brigham proposed a social to show “to the world that this people can be made what God designed them. Nothing will infringe more upon the traditions of some men than to dance,” he declared, noting that “the Lord said He wanted His saints to praise Him in all things.” He further noted that “for some weeks past I could not wake up at any time of the night but I heard the axes at work. Some were building for the destitute and the widow; and now my feelings are, dance all night, if you desire to so do, for there is no harm in it. . . . I enjoin the Bishops that they gather the widow, the poor and the fatherless together and remember them in the festivities of Israel.”[98]

While understanding the need for recreation, Brigham also understood the need for moderation and raised a warning voice against individuals allowing diversions to consume their lives. To the vanguard company he declared: “There is no harm [that] will arise from merriment or dancing if Brethren, when they have indulged in it, know when to stop. But the Devil takes advantage of it to lead the mind away from the Lord.”[99]

While at Winter Quarters, someone established a “dancing school” that Brigham attended.[100] After reaching the Salt Lake Valley, Brigham oversaw the establishment of such a school and pushed for the Saints to build social halls and theaters. At one point he became so concerned about the social needs of the Saints that he sent a circular letter to each bishop offering advice on holding ward socials.[101]

Clarissa Young Spencer concluded, “One of Father’s most outstanding qualities as a leader was the manner in which he looked after the temporal and social welfare of his people along with guiding them in their spiritual needs.”[102] Another daughter, Susa Young Gates, felt that her father “manifested even more godly inspiration in his carefully regulated social activities and associated pleasure than in his pulpit exercises. He kept the people busy, gave legitimate amusements full sway and encouraged the cultivation of every power, every gift and emotion of the human soul.” She noted that “people would have had in those grinding years of toil, too few holidays and far too little of the spirit of holiday-making which is the spirit of fellowship and socialized spiritual communion, but for Brigham Young’s wise policy.”[103] As with other aspects of the “Word and Will of the Lord,” while the implementation and successful oversight were Brigham’s, the inspiration was the Lord’s.

Trials, Persecution, and the Martyrdom

The revelation also discussed the trials and persecutions the Saints’ had endured: “My people must be tried in all things, that they may be prepared to receive the glory that I have for them, even the glory of Zion; and he that will not bear chastisement is not worthy of my kingdom” (v. 31). Brigham subsequently taught that “in everything the Saints may rejoice,” including persecution, since it was “necessary to purge them, and prepare the wicked for their doom.”[104]

Concerning the scourges the Saints had collectively endured in Ohio, Missouri and Illinois, Brigham declared: “If we did not exactly deserve it [at the time], there have been times when we did deserve it. . . . It was good for [us] and gave us an experience.”[105] On the fifth anniversary of the Saint’s arrival in the Salt Lake Valley he proclaimed: “Be humble, be faithful to your God, true to His Church, benevolent to the strangers that may pass through our territory, and kind to all people; serving the Lord with all your might, trusting in him. . . . [Someday] we will celebrate our perfect and absolute deliverance from the power of the devil; [but] we only celebrate now our deliverance from the good brick houses we have left [at Nauvoo], from our farms and lands, and from the graves of our fathers.”[106]

Brigham counseled the Saints to “cast all bitterness” out of their hearts.[107] Regarding the wrongs they had suffered, he reiterated the Lord’s injunction that individuals must forgive, or “there remaineth in [them] the greater sin. . . . Ye ought to say in your hearts—let God judge between me and thee, and reward thee according to thy deeds.”[108] In March 1852 Brigham proclaimed: “Suppose every heart should say, if my neighbor does wrong to me, I will not complain, the Lord will take care of him. Let every heart be firm, and every one say, I will never contend any more with a man for property, I will not be cruel to my fellow-creature, but I will do all the good I can, and as little evil as possible. . . . I wish men would look upon that eternity which is before them. . . . It is a source of mortification to me to think that I ever should be guilty of doing wrong, or of neglecting to do good to my fellow men, even if they have abused me.”[109] Five years later he wrote in his journal, “I wish to meet all men at the judgment Bar of God without any to fear me or accuse me of a wrong action.”[110]

In multiple verses (17, 30, 34–36, 40–42) the Lord specifically addressed the enemies of the Church. Verse 17 instructed the Saints to “fear not thine enemies; for they shall not have power to stop my work,” while verse 30 stated, “Fear not thine enemies, for they are in mine hands and I will do my pleasure with them.” Brigham frequently addressed this idea during the early days in the valley. In 1850 he wrote: “We feel no fear. We are in the hands of our heavenly Father, the God of Abraham and Joseph who guided us to this Land. . . . He is our Father and our Protector. We live in his Light, are Guided by his Wisdom, Protected by his Shadow, Upheld by his Strength.”[111] Later he told the Saints that if they would do “the will of God . . . there is no fear from any quarter.”[112] He also counseled, “I want you to bid farewell to every fear, and say God will take care of his kingdom. . . . It is he who has preserved us—not we.”[113]

As soldiers with the U. S. Army approached Utah in August 1857 during the so-called Utah War, Brigham reassured the Saints: “Cannot this Kingdom be overthrown? No. They might as well try to obliterate the sun. . . . God is at the helm. . . . Do not be angry with [the army], for they are in the hands of God. Instead of feeling a spirit to punish them, or anything like wrath, you live your religion.”[114] The following month as the immediate threat of armed conflict began to diminish, Brigham wrote to Church leaders in southern Utah: “God rules. He has overruled for our deliverance this time once again and he will always do so if we live our religion, be united in our faith and good works. All is well with us.”[115]

Initially, Brigham gave vent to strong feelings following the martyrdom. “I have never yet talked as rough in these mountains as I did in the United States when they killed Joseph,” he noted.[116] While the emotional wounds brought on by the death of his friend and mentor were deep, the Lord’s declaration in “The Word and Will” helped remind him that they need not be long lasting. “I took him [Joseph] to myself. Many have marveled because of his death; but it was needful that he should seal his testimony with his blood, that he might be honored and the wicked might be condemned” (v. 38–39).

In 1849 Brigham told the Saints that Joseph “lived just as long as the Lord let him live. But the Lord said, ‘Now let my servant seal up his testimony with his blood.’”[117] Later he reminded the Saints, “If it had been the will of the Lord that Joseph and Hyrum should have lived, they would have lived.”[118]

While Brigham’s critics have long portrayed him as a man bent on avenging past wrongs the Saints had endured, including the martyrdom of Joseph and Hyrum, Brigham did not fixate on those wrongs. “It is very seldom that I refer to past scenes,” he noted in 1856. “They occupy but a small portion of my time and attention. Do you wish to know the reason of this? It is because there is an eternity ahead of me, and my eyes are ever open and gazing upon it.”[119] On another occasion he proclaimed: “Instead of crying over our sufferings, as some seem inclined to do, I would rather tell a good story, and leave the crying to others.”[120]

He declared that “all evil is contrary to our covenants and obligations to God” and taught that to “make the doing of God’s will and the keeping of his commandments a constant habit” will cause it to “become perfectly natural and easy for you to walk uprightly before Him.”[121] He further taught: “Let us live so that we can say we are the Saints of God; and when the finger of scorn is pointed at us and we are held in derision and the nations talk about us, let us show an example before them that is worthy of imitation, that they cannot but blush before all sensible and intelligent persons when they say, ‘There is a people that sin; there is a people that are corrupt.’ . . . Let them howl and bark against us as much as they please, but let us live so that they have no reason to say a word.”[122]

“Be Diligent in Keeping All My Commandments”

The “Word and Will” closed with the Lord’s warning that the Saints needed to “be diligent in keeping all my commandments, lest judgments come upon you, and your faith fail[s] you, and your enemies triumph over you. . . . Amen and Amen” (v. 42). As president of the Church, Brigham raised a warning voice along these same lines. “If persons neglect to obey the law of God and to walk humbly before Him darkness will come into their minds and they will be left to believe that which is false and erroneous,” he declared. “Their minds will become dim, their eyes will be beclouded and they will be unable to see things as they are.”[123] On another occasion he taught: “If the Saints neglect to pray, and violate the day that is set apart for the worship of God, they will lose his Spirit. If a man shall suffer himself to be overcome with anger, and curse and swear, taking the name of the Deity in vain, he cannot retain the Holy Spirit. In short, if a man shall do anything which he knows to be wrong, and repenteth not, he cannot enjoy the Holy Spirit but will walk in darkness and ultimately deny the faith.”[124]

Addressing a comment of an individual who publicly proclaimed his intention to stay in the Church, Brigham declared: “What in the name of common sense is there to hang on to, if [one] does not hang on to the Church? I do not know of anything. You might as well take a lone straw in the midst of the ocean to save yourselves. . . . There is nothing but the Gospel to hang on to!”[125]

Summary

While section 136 immediately provided Brigham the answers that he needed to lead the Church at a pivotal time in his presidency, the long-term lessons he learned regarding the importance of keeping sacred covenants and obeying the revealed word of the Lord remain relevant today. The revelation serves as a testament that the Lord reveals his secrets—including secrets of ultimate success and true happiness—to “his servants the prophets.”[126] It also serves as a reminder that all individuals can receive for themselves the “Word and Will of the Lord” to help them with their own circumstances and challenges.

Notes

[1] Doctrine and Covenants 68:4 defines the word of the Lord as “the power of God unto Salvation.”

[2] For a more in depth look at the Mormon exodus from Nauvoo to Utah and the circumstances surrounding Brigham Young’s receiving the “Word and Will of the Lord,” see Richard E. Bennett, We’ll Find the Place: The Mormon Exodus, 1846–1848 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1997).

[3] Brigham’s actions after receiving section 136 are consistent with what the prophet Alma taught in his discourse on faith: “We will compare the word to a seed. Now, if ye give place, that a seed may be planted in your heart, behold, if it be a true seed, or a good seed, if ye do not cast it out by your unbelief, that ye will resist the Spirit of the Lord, behold, it will begin to swell within your breasts; and when you feel these swelling motions, ye will begin to say within yourselves—It must needs be that this is a good seed, or that the word is good for it beginneth to enlarge my soul; yea, it beginneth to enlighten my understanding, yea, it beginneth to be delicious to me.” (Alma 32:28).

[4] Brigham moved up the date when the Saints would begin leaving Nauvoo in part because he believed that “God will rule the elements, and the Prince and power of the air will be stayed” (Historian’s Office, History of the Church, January 24, 1846, Church History Library, Salt Lake City).

[5] Helen Mar Kimball Whitney, “Our Travels beyond the Mississippi,” Women’s Exponent, 1 December 1883, 102.

[6] Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 3 May 1846.

Eleven weeks after Brigham Young left Nauvoo, his company had only traveled about 145 miles and barely made it halfway across Iowa. Something needed to change if he and other members of the company were to reach the Salt Lake Valley that year. On 26 April, Brigham directed the company to begin work on a settlement where members that were slowing their progress could stop to rest and regain their strength, resupply, and seek out better outfits. For a little over two weeks, men split rails; built houses, fences, and bridges; dug wells; and cleared, plowed and planted fields. When the company moved out of this new community, which they named Garden Grove, several hundred Saints remained behind.

A short distance later in a last-ditch attempt to reach the Rocky Mountains, the company again stopped for two weeks beginning May 18 to create a second settlement that they called Mount Pisgah. Brigham now ordered other company members to stop until they were better able to undertake the journey. Prior to the company leaving Mt. Pisgah, a number of the Saints who had left Nauvoo around the first of May as originally planned caught up with the advance company, a fact that likely added to Brigham’s anxiety and frustration. William G. Hartley and A. Gary Anderson, Iowa and Nebraska, vol. 5, Sacred Places: A Comprehensive Guide to Early LDS Historical Sites, edited by Lamar C. Berrett (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2006), 72, 74–75, 83, 86.

While the settlements of Garden Grove and Mount Pisgah were initially viewed as necessary to help speed the journey of the advance company, later that year they would become home to thousands of additional Latter-day Saints who needed a place to winter.

[7] William Clayton, “Come, Come, Ye Saints,” Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 30.

[8] Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 7 January 1847.

[9] Brigham Young to Jesse C. Little, 6 February 1847, General Correspondence, Outgoing, Brigham Young Office Files, Church History Library; Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 1:166.

[10] In a revelation to the Prophet Joseph Smith, the Lord declared: “And my people must needs be chastened until they learn obedience, if it must needs be, by the things which they suffer” (D&C 105:6).

[11] Like Joseph Smith before him, Brigham Young found the words of James to be true: “If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and abraideth not; and it shall be given him. But let him ask in faith, nothing wavering” (James 1:5–6).

The fact that Brigham received section 136 in the middle of the westward journey and not prior to leaving Nauvoo is consistent with the truth taught by Elder Richard G. Scott during the April 2007 General Conference: “I wonder if we can ever really fathom the immense power of prayer until we encounter an overpowering, urgent problem and realize that we are powerless to resolve it. Then we will turn to our Father in humble recognition of our total dependence on Him” (Richard G. Scott, “Using the Supernal Gift of Prayer,” Ensign, May 2007, 8).

When the 2013 LDS edition of the scriptures was published, the date for the revelation was accidently deleted from the section introduction. Hosea Stout was present at the council meeting where “the word of the Lord was obtained.” He noted in his journal that it was “a source of much joy and gratification to be present on such an occasion and my feeling can be better felt than described.” Hosea Stout diary, 14 January 1847, as published in Juanita Brooks, On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press and Utah State Historical Society, 1982), 1:227, 229. For other references to the date of the revelation having been received on January 14 see Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 14 January 1847, and Wilford Woodruff journal, 14 January 1847, Wilford Woodruff Collection, Church History Library.

[12] Proverbs 3:5–7 states the concept this way: “Trust in the Lord with all thine heart; and lean not unto thine own understanding. In all thy ways acknowledge him, and he shall direct thy paths. Be not wise in thine own eyes; fear the Lord, and depart from evil.”

[13] Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 17 January 1847.

[14] Having adopted the organizational principles outlined in the revelation, Church leaders would adapt them to individual circumstances. While emigrating companies were organized with a presidency, the division into tens, fifties and hundreds became a guiding principle rather than hard and fast numbers. Actual divisions within a company usually reflected the makeup and needs of that company.

[15] Historian’s Office, History of the Church, January 14, 1847.

[16] Exodus 18:21–23.

[17] Following the expulsion of the Latter-day Saints from Jackson County, Missouri, Joseph Smith led an expedition from Kirtland, Ohio, to western Missouri, during May and June 1834, in an attempt to regain the land from which they had been expelled. A revelation given to the Prophet Joseph declared that if the Saints would allow the Lord to lead them, they would be able to redeem Zion. In this revelation, the Lord also made reference to Moses and the exodus (D&C 103:15–18). A subsequent revelation declared that Zion’s Camp was unsuccessful in its stated purpose because the Saints had “not learned to be obedient to the things which I required at their hands, but are full of all manner of evil, and do not impart of their substance, as becometh saints, to the poor and afflicted among them; and are not united according to the union required by the law of the celestial kingdom” (D&C 105:3–4). Ultimately, the Prophet Joseph disbanded the expedition rather than attempt to redeem Zion through violence.

[18] The organizational concepts revealed in the revelation, along with those which Brigham initiated on his own, remain at the heart of how the Church is organized today. Rather than being organized into emigrating companies, Latter-day Saints are now part of branches, wards, districts, and stakes, each of which has a “presidency,” “captains” that have direct responsibility for smaller groups within each unit, and a defined membership established upon guiding principles regarding the size of units.

[19] Bennett, We’ll Find the Place, 73.

[20]“Twelve Apostles to the Saints,” 27 January 1847, as included in Historian’s Office, History of the Church, January 27, 1847.

[21] Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 16 January 1847.

[22] Hosea Stout diary, 22 March 1847, as published in Brooks, On the Mormon Frontier, 1:242.

[23] Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 2 April 1847; Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 26 March 1847.

[24] Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 21 March 1847.

[25] Hosea Stout diary, 15 March 1847, as published in Brooks, On the Mormon Frontier, 1:241. Brigham and the Twelve also counseled “those who remain” that they had a responsibility to “do all they can” to assist those who were going to the valley in 1847 since they would be preparing a place for them to settle. Church leaders concluded that this type of cooperation, coupled “with a little time and patience, and a great deal of active industry,” would result in “every man and woman” one day being “found in their own order and place amidst the habitations of the righteous.” “Twelve Apostles to the Saints,” 27 January 1847, as included in Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 27 January 1847.

[26] In addition to those who continued to put forth claims that they were Joseph’s appointed successor to lead the Church, another potential challenger to the authority of the Twelve in the minds of some was the Council of Fifty. Established in Nauvoo by Joseph Smith shortly before his death to help establish the political Kingdom of God in the Saints new home in the Rocky Mountains, it had also played a role in planning the westward trek from Nauvoo. The “Word and Will” served as a reminder that the Council, although including members of the Twelve, was subservient to priesthood authority. For more information on the Council of Fifty, see Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith, The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017). Although it is a common practice today to reorganize the First Presidency soon after the death of a prophet, it was not until December 1847, two and a half years following the martyrdom, that Brigham Young was sustained as president of the Church and the First Presidency was reconstituted.

[27] Hosea Stout diary, 14 January 1847, as published in Brooks, On the Mormon Frontier, 1:229.

[28] In addition to the five individuals mentioned in the revelation, the vanguard pioneer company included three other members of the Twelve—Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and Willard Richards, who would form the First Presidency when it was reorganized in December 1847. Parley P. Pratt and John Taylor arrived in Winter Quarters shortly before the company left, but chose instead to travel later in the year. Orson Hyde was appointed to remain behind to oversee affairs at Winter Quarters and surrounding settlements until Brigham Young returned. The final member of the Twelve, Lyman Wight, had previously gone to Texas with a small group of followers and would subsequently be excommunicated for apostasy.

[29] Brigham had recognized prior to this time that the Saints’ behavior had played a role in their problems but was not certain how best to address the problem. In late December 1846, he had raised the possibility of implementing “a reformation” among the Saints so “that all might exercise themselves in the principles of righteousness,” but had not acted upon the idea. Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 20 December 1846.

[30] Exodus 18:20.

[31] Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 27 January 1847. In presenting the revelation to the Saints at Ponca, Nebraska, Brigham wrote that the revelation “has become a law unto all saints” and that “union, obedience, and brotherly love, will secure you from future dangers.” Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 27 January 1847. Previously the Lord had declared: “Behold, I give unto you a commandment, that when ye are assembled together ye shall instruct and edify each other, that ye may know how to act and direct my church, how to act upon the points of my law and commandments, which I have given. And thus ye shall become instructed in the law of my Church and be sanctified by that which ye have received, and ye shall bind yourselves to act in all holiness before me” (D&C 43:8–9).

[32] Brigham Young to William Huntington, 28 June 1846, General Correspondence, Outgoing, Brigham Young Office Files.

[33] Brigham was not alone in this view. After hearing the revelation read, Horace Eldredge publicly declared that “its execution would prove our salvation.” Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 16 January 1847. In 1855 Brigham expounded further upon the importance of obedience: “We are fast becoming a great people, but it is not so much numbers that will make us mighty as it is purity[,] faithfulness and obedience and submission to the requirements and will of the Lord our God. Let us continually seek unto him for wisdom and strength to keep his commandments and perform our duties as good and faithful servants, before him keeping ourselves pure and holy and walking blameless in all of his ordinances.” Brigham Young to John Van Cott, 20 June 1855, General Correspondence, Outgoing, Brigham Young Office files.

[34] As the vanguard company began its journey, Brigham declared that he wanted the company to “go in such a manner as to claim the blessings of Heaven.” Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 15 April 1847.

[35] For a look at the covenants that Latter-day Saints make see “Understanding Our Covenants with God,” Ensign, July 2012, 22–25. Brigham later taught that “all the sacrifice that the Lord asks of his people is strict obedience to our own covenants that we have made with our God, and . . . to serve him with an undivided heart.” Brigham Young discourse, 21 June 1874, as published in Journal of Discourses, 18:246.

[36] The Lord had promised the Saints that through temple ordinances he would “endow those whom I have chosen with power from on high” (D&C 95:8). At the same time, he warned that the realization of this power was dependent upon behavior: “If you keep not my commandments, the love of the Father shall not continue with you, therefore you shall walk in darkness” (D&C 95:12). Instead of claiming the promised blessings associated with their covenants, the Saints in essence had been “walking in darkness at noon-day” during their journey (D&C 95:6).

[37] 1 Nephi 2:20; 17:13–14. Following his journey, Nephi declared: “My God hath been my support; he hath led me through mine afflictions in the wilderness; and he hath preserved me upon the waters of the great deep. . . . O Lord, I have trusted in thee, and I will trust in thee forever. I will not put my trust in the arm of flesh; for I know that cursed is he that putteth his trust in the arm of flesh. Yea, cursed is he that putteth his trust in man or maketh flesh his arm” (2 Nephi 4: 20, 34).

[38] D&C 105:2–3.

[39] Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 18 January 1847.

[40] Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 18 January 1847. Previously the Lord had declared, “Look to me in every thought; doubt not, fear not” (D&C 6:36).

[41] Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 3 March 1847.

[42] Norton Jacob journal, 23 May 1847, as published in Ronald O. Barney, The Mormon Vanguard Brigade: Norton Jacob’s Record (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2005), 145; spelling standardized. It was in the context of covenant keeping and obedience that the Lord declared, “I, the Lord, am bound when ye do what I say; but when ye do not what I say, ye have no promise” (D&C 82:10).

[43] Historian’s Office, General Church Minutes 1839–1877, 23 May 1847, Church History Library; spelling standardized. Isaiah 48:17–18 states, “Thus said the Lord, thy Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel; I am the Lord thy God which teacheth thee to profit, which leadeth thee by the way that thou shouldest go. O that thou hadst hearkened to my commandments! then had thy peace been as a river, and they righteousness as the waves of the sea.” See also 1 Nephi 20:17–18.

[44] Although it is widely believed that the vanguard company only ever consisted of 143 men (plus 3 women and 2 children), in reality 144 men began the journey. After having traveled to the rendezvous location on the Elkhorn River, Ellis Eames dropped out of the company on April 18. According to William Clayton, the reason was “poor health, spitting blood, etc.” William Clayton diary, 18 April 1847, Church History Library. Due to the short time he spent with the company, Eames has often not been listed among its members.

[45] While Orson F. Whitney was one of the first to note that “twelve times twelve men had been chosen,” he also concluded, “Whether designedly or otherwise we know not.” Orson F. Whitney, History of Utah, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon and Sons, 1892–1904), 1:301.

[46] Clayton diary, 29 May 1847.

[47] Historian’s Office, General Church Minutes, 23 May 1847; Woodruff journal, 16 May 1847.

[48] Although some members of the company had left their homes in late March, it was not until mid-April that the company was officially organized prior to leaving its rendezvous location on 17 April at the Elkhorn River approximately 27 miles west of Winter Quarters.

[49] Woodruff journal, 28 May 1847.

[50] Clayton diary, 29 May 1847.

[51] In addition to how they were traveling, the number in this combined company was likely also a concern to Brigham. Unlike the previous year when the goal was to get everyone to the Salt Lake Valley, the Twelve had decided that only “about one hundred families should follow the Pioneers, including as many of the soldiers families as could be fitted out.” Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 21 March 1847.

[52] Historical Department, Office journal, 15 June 1847, Church History Library.

[53] Historian’s Office, General Church Minutes, 4 September 1847; spelling standardized. Wilford Woodruff described this meeting of the Twelve as “one of the most interesting Councils we ever held together on the earth.” He noted that Pratt and Taylor were “reproved Sharply for undoing what the majority of the quorum had done in the organizing of the camps for travelling,” in which they had “spent the whole winter in organizing & which was Also governed by revelation.” Woodruff journal, 4 September 1847.

[54] Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 28 June 1846.