Introduction

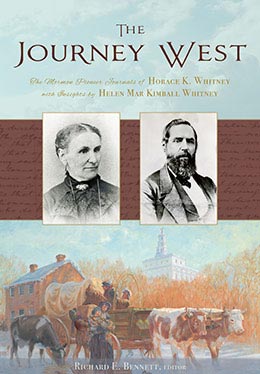

Richard E. Bennett, "Introduction," in The Journey West: The Mormon Pioneer Journals of Horace K. Whitney with Insights by Helen Mar Kimball Whitney, ed. Richard E. Bennett (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), ix–xxxviii.

There are many unwritten incidents which could be related with profit, and prove interesting reading to those who pioneered across the barren, trackless wastes of the great American desert to these once lone and dreary vales of the Rocky Mountains, as well as scores who are not of that number and even many strangers would enjoy reading of those early scenes among the “Mormons.” . . . I mention this as a stimulus to prompt others to write and give to the world the benefit of their travels and experience with this people.

—Helen Mar Whitney, Woman’s Exponent, vol. 15, no. 6,

15 August 1886, pp. 46–47

One of the ironies of Mormonism is that, although it is an American religion, the United States of America has struggled to accept it. In fact, the early history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is one long chapter of rejection, persecution, and expulsion. For years after its founding in upstate New York under the hand of Joseph Smith Jr. in April 1830, the church was on the run from pillar to post: first, New York; then Kirtland, Ohio; Independence and Far West, Missouri; Nauvoo, Illinois; and finally, the Rocky Mountains. Scholars have long argued over what poisoned the mix. Perhaps it was its radical claim of being the only true and restored church of Christ upon the earth. Or its adamant belief in the divine authenticity of the Book of Mormon, which Smith translated from ancient golden plates that he discovered in upstate New York. Furthermore, its fervent expectation in the imminent Second Coming of Christ to its new Zion in Jackson County, Missouri, seemed peculiar at best to local citizens bent on establishing a new home in the West.

Whatever the case, many Americans came to believe that the allegiance of most early Mormons was more to their prophet than to the president, more to revealed scripture than to the American Constitution. There may have been too much talk of a kingdom of God for a restless republic of the people to accept. And when large concentrations of Latter-day Saint “Yankees” began moving to the slave state of Missouri in the early 1830s intent on establishing their Zion, it inevitably created a climate of suspicion and distrust amidst a clash of cultures that eventually led to their undoing. The sad fact is Mormonism could not have chosen a more difficult time, a less promising place, amidst a more unwelcoming people to establish their New Jerusalem than in Missouri in the early 1830s.

The tragic expulsion of the Mormons from Missouri in the winter of 1838–39 under the threat of “extermination” as decreed by Governor Lilburn W. Boggs led to a forced two- hundred-mile march of several thousand Mormons from the far west of Missouri to Quincy, Adams County, in the more accepting “free” state of Illinois. There, over the next seven years, they finally established a home in their beloved Nauvoo, where they hoped to build a permanent settlement and to live and worship as they pleased. By 1844, some twelve thousand Latter-day Saints from the eastern United States, Canada, and Great Britain were crowding into their new surroundings in Nauvoo, and for a time their future looked promising.

But by 1844 the Saints were again facing all kinds of trouble. Many Missourians continued to hold grievances against them and plotted to recapture their prophet-leader. With Nauvoo threatening to become an economic powerhouse, other slower-growing nearby river towns, like Warsaw, stood to lose valuable business. And when rumors began to fly that Joseph Smith and a few other Mormon leaders were secretly practicing polygamy, many former friends and members turned suspicious and began speaking of conspiracy and kingdom building. “Saintly scoundrels” such as John C. Bennett, former mayor of Nauvoo, falsely charged that the city militia—the Nauvoo Legion—was plotting militarily against the very existence of the nation. When Joseph Smith announced in 1844 that he would seek the presidency of the United States in large measure to seek redress for Missouri’s depredations upon the Saints, his growing chorus of critics branded him a political and religious megalomaniac, a prophet without constraint, one certainly “without honor” in his own country. In short, the anti-Mormon press tried every which way to label Mormonism as an anti-American, anti-Christian, and anti-family religion—a lethal triplet of unfounded charges which nonetheless led inexorably to the murder of Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum in Carthage Jail in June 1844. Many expected their death would put an end to Mormonism once and for all.

Although Sidney Rigdon, James Strang, and others laid claim to Smith’s mantle of prophetic leadership, Brigham Young eventually held sway. As shrewd a leader as he was sympathetic to the plights of his people, “Brother Brigham,” in his capacity as president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, recognized that there was no future for the church in Illinois. By 1845, he and the Council of Fifty, a highly influential political advisory body to church leadership, were quietly laying plans for a departure west to some new home far away where they could finally live their peculiar religion in peace. On behalf of the entire council, Orson Spencer indicated that the Saints were “willing to accept of any eligible location within any part of the Territory of the U. States” so long as it was large enough to accommodate at least five hundred thousand people.[1] Faced with the threat of his own assassination, the possible interference of their westward march by a United States Army of the West, and potential defections in greater numbers, Brigham Young began to lead his people out of Nauvoo in the teeth of a very cold February of 1846. Their plan was to reach Council Bluffs on the Missouri River in a matter of weeks, establish farms and way stations at Grand Island and elsewhere in what is today Nebraska,[2] and from there dispatch a speedy vanguard company of pioneers over the mountains to some large valley all in 1846, that memorable “Year of Decision,” as historian Bernard DeVoto so aptly termed it.[3]

Alas, it was not to be. Instead of an express vanguard company of one or two hundred handpicked pioneers, soon 2,500 Saints rapidly crowded around their leader. Such a large, relatively unprepared company hedged up his way. Instead of leaving their Sugar Creek encampments just across the river from Nauvoo in early March, they languished there until mid-April. When finally they did begin to roll out across Iowa Territory, the rains came, incessant and torrential, so much so that instead of making their planned fifteen miles a day, they barely made one. With wagons sunk to their axles in mud day after weary day, many began to wonder whose side God was on after all. Desperately seeking his way across a three-hundred-mile-long Iowa mudhole, Brigham Young ordered most of his struggling, rain-soaked followers to start building their proposed way stations much sooner than anticipated. They first identified Garden Grove (just 143 miles west of Nauvoo) and then Mount Pisgah, Iowa (192 miles west) as places to build habitations and put in spring crops for the thousands yet to follow. Later that summer he instructed others to return to Nauvoo with vacated wagons to bring on the “poor camps” of refugees being hounded out of Nauvoo by mad militia mobs intent on destroying whatever vestige of Mormonism there remained. Under miserable skies, miscommunications, and misunderstandings and one failed timetable after another, their entire plan of exodus was in disarray. Many of his followers were sick and about to die from near starvation, sheer exhaustion, and the cruel and unrelenting exposure to the elements. Not only were their westering plans in doubt, but the very salvation of the church was at stake.

The Army of the United States did indeed come as earlier feared, but instead of interfering, it came inviting. With the expansionist-minded President James K. Polk anxious to declare war against Mexico to ensure the annexation of California, Captain James Allen of Stephen W. Kearny’s Army of the West caught up with the Mormons at Mount Pisgah in early June of 1846 and there asked for a battalion of five hundred of their strongest, healthiest men to enlist. Indignant to serve a nation many felt had consented to driving them out, the “Mormon Battalion” ultimately listened to the persuasions of one Colonel Thomas L. Kane of Philadelphia, a friend of both Polk and the Mormons. At his assurances, the embarked upon one of the longest overland marches in military history: from Fort Leavenworth to San Diego, a distance of 1,618 miles, where many were honorably discharged having never fired a shot in hostile action. Several, however, reenlisted and marched another five hundred miles north, where they participated in finding gold at Sutter’s Fort, near Sacramento, in 1848. Yet instead of staying on and making their fortunes, most of them headed east several hundred more miles to rejoin their families either in the Salt Lake Valley or, as was the case with many, somewhere back along the Mormon Trail. Thus some of the Mormon Battalion men marched more than three hundred miles!

Meanwhile, back in Iowa, Brigham Young and his vanguard company finally reached the Missouri River in mid-June, much too late—as every trader and mountain man knew well—to make a dash for the Rocky Mountains, a sad truth that the Donner-Reed party would learn the hard way that same year. In the fall of 1846, with reluctant permission from military officials to settle on Indian lands located on the west banks of the Missouri River in what today is Omaha, the Mormons established their Winter Quarters settlement, Nebraska’s first city. By the end of the year, four to five thousand were settled there, with a comparable number across the river in Council Bluffs (which they renamed Kanesville) and another three to four thousand strewn all across Iowa clear back to the Mississippi. Some stayed in St. Louis and in other Missouri river towns. While some murmured and more than a few defected, the vast majority of the Saints remained faithful to the leadership of Brigham Young.

After enduring a winter of suffering and death, the long-hoped-for spring of 1847 finally arrived. Brigham Young wasted no time in leading out his handpicked, hearty band of pioneers to find a new home in the West. His pioneer company of 148 (143 men, 3 women, and 2 children) left the Elkhorn River in early April and pioneered their own trail north of the Platte River so as not to interfere with the more crowded Oregon and California Trail followers on the south side, many of whom were from Missouri. Enjoying much better weather than the year before, they reached Chimney Rock (the approximate halfway point) on 28 May, Fort Laramie by 2 June, and Independence Rock by 21 June, from whence they followed the South Pass down and across the Green River to Fort Bridger. From there, they decided to travel down Echo and other canyons westward to scout out the Valley of the Great Salt Lake, where, on 24 July 1847 Brigham Young, though sick with Rocky Mountain spotted fever, declared it to be “the right place. Drive on!”[4] Their long journey now at an end, the word soon went out for all to come. And come they did. Eventually, tens of thousands of new converts from Great Britain, Scandinavia, and elsewhere found their way by ship, wagon, and even handcarts to their new mountain Zion.

The Mormon exodus was that of an entire believing people fleeing out of Babylon to a new mountain home “far away in the West” (to borrow William Clayton’s phrase),[5] where they could worship without fear of persecution. They came to believe, as Brigham Young’s “Word and Will of the Lord” revelation at Winter Quarters stated, that they would find their place if they followed their God. In the process, they forged a character and an identity that to this day sets the Latter-day Saints apart from the rest of America, if not in an ethnic way, then certainly in a religious one. It is within this rich and unfolding drama that the Horace K. Whitney journals and the accompanying selective reminiscences of his wife must be understood and appreciated.

Children of the Restoration

Horace Kimball Whitney and Helen Mar Kimball (Smith) Whitney are a unique couple in Latter-day Saint history. While most early Mormon diarists and correspondents converted to the church later in life and migrated to join the fledgling Latter-day Saint movement, Horace and Helen were children of the Restoration, childhood acquaintances, if not sweethearts, from two of the most prominent convert families in Kirtland, Ohio. Born in 1823, Horace was the oldest son of Newel K. Whitney, the second presiding bishop of the church. Helen Mar, daughter of Heber C. Kimball, a member of the original Quorum of the Twelve, was five years his junior. The two grew up together in the shadow of the Kirtland Temple, moved on to Nauvoo with their parents, and eventually married one another in the Nauvoo Temple just one day before the Mormon exodus to the Salt Lake Valley began in early February 1846. One might say they saw it all in that they lived through the exciting, if not deeply troubling, growing pains of the young Church of Jesus Christ under the leadership of their prophet, Joseph Smith Jr. They suffered along with the rest of their fellow believers, losing their first three children to the rigors of the exodus, but their sorrows never gave way to faithlessness, hopelessness, or despair. Instead, they chose to see life and its incessant challenges through the confident lens of youthful love and abiding optimism, full of hope and faith. As Joseph Conrad once penned about such youthful exuberance and adventure, “I remember my youth and the feeling that will never come back any more—the feeling that I could last for ever, outlast the sea, the earth, and all men; . . . the triumphant conviction of strength, the heat of life in the handful of dust.”[6] For Helen and Horace, the sea that they were about to cross was what many then called the Great American Desert.

Horace Kimball Whitney

Horace Kimball Whitney was born in Kirtland, Ohio, 25 July 1823, the oldest child of Newel K. and Elizabeth Ann (Smith) Whitney. His father, a prominent and successful store owner and operator, and his mother, a goodly woman full of Christian faith and integrity, converted to Mormonism in November 1830 when Parley P. Pratt, Oliver Cowdery, Ziba Peterson, and Peter Whitmer Jr. came to town with their message of the Book of Mormon and the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. In early February 1831, Horace first met Joseph Smith Jr., the Mormon prophet, who upon arriving in Kirtland said to Horace’s father, Newel K. Whitney, “You prayed me here. What do you want of me?” Joseph Smith soon afterwards called Brother Whitney as bishop of the church in Kirtland. Baptized when nine years old by Reynolds Cahoon, Horace ever revered Joseph Smith as the prophet of God. Many a night by the hearth of the Whitney home as the fire crackled and the candles flickered, he listened to Joseph Smith tell of his spiritual quests, his visions and blessings, and the translation of the Book of Mormon, believing with the total trust of a young boy.

Horace’s parents, more well-to-do than most, made sure that their son received a first-rate education, providing him with every advantage of schooling that his time and environment could afford. Because of it, he acquired a thirst for learning that would last a lifetime. When his bedroom candles burned out at night, he would often open his window with his books in hand to read by the light of the moon. “Ask Horace” became a proverb among his boyhood friends when seeking information upon almost every topic. He ever looked back with fondness upon the opportunity he had of learning from Joseph Smith, Heber C. Kimball (his future father-in-law), Brigham Young, and other church leaders in the Hebrew school held in the upstairs of his own home where he learned Hebrew, Latin, and Greek as well as English. Blessed with a quick and impressionable mind, he learned faster than most and received one ribbing after another from those who loved and admired him for racing ahead of them. A careful notetaker and observer, Horace loved literature, history, and the study of books. His memory was, as one put it, “like hooks of steel.”

While others may have sought him out, Horace was never one to seek the limelight. He was a sensitive, unassuming, and rather modest young lad, and though a lively conversationalist, he shunned popularity and position. He was most comfortable as a follower, not the ambitious leader, and had a reputation for honesty and integrity. A better writer than a preacher, Horace once admitted, “Were preaching an employment by which to earn one’s livelihood, and I had chosen it as such, my nervous excitement on attempting to speak would warn me that I had mistaken my calling.”[7]

Growing up, young Horace witnessed the many ups and downs of Kirtland. New converts by the hundreds continued to pour into the city from all over the eastern United States. Meanwhile, the Prophet proclaimed a spate of visions and revelations, established new positions in the church, and made exciting new proclamations, foremost of which was his call for the Saints to construct the Kirtland Temple in their poverty, beginning in 1833. Now a strapping young man, Horace helped out as much as he could. In April 1836, with the temple’s dedication, several claimed to see celestial beings surround the structure in what has gone down in church history as a Pentecostal season of spiritual manifestations.

In vivid contrast, he also witnessed the rise of rancor, bitterness, and finger-pointing among the Saints with the collapse of the Kirtland Safety Society Anti-Banking Company, an economic hardship largely attributable to the nationwide Panic of 1837. Once harmonious feelings deteriorated into acrimony, distrust, defection, and persecution, so much so that the Whitney family felt compelled to quit their city for their own safety and join in with some five hundred others in the so-called “Kirtland Camp” of 1838 for a new “Zion” home in Missouri.

Fifteen-year-old Horace, however, never made it to Missouri. Upon arriving in St. Louis and hearing that the Saints in Missouri were facing an extermination and expulsion order courtesy of Governor Lilburn W. Boggs in the late fall of 1838, the Whitney family decided to spend the winter in Carrollton, Greene County, Illinois, some twenty-five miles north of St. Louis. There Horace obtained employment as a country teacher, despite his youthful age. Being large in stature and slightly bearded, Horace came off older and more mature looking than most others his age. When the examining trustee queried, “I should say you were about twenty-one, Mr. Whitney,” he replied, “You needn’t guess again,” and the examination closed.

Within a year, however, the Whitney family was on the move again, this time north to join the Saints in their settlement of Commerce, Illinois, which Joseph Smith—fresh out of Liberty Jail—rechristened Nauvoo, the “City Beautiful.” While his father took up his duties as presiding bishop of the church, Horace once again taught school for a season, teaching reading, writing, and arithmetic to a handful of students at a fee of three dollars a quarter.[8] Once settled in Nauvoo, he also learned the printer’s trade and was employed with the Times and Seasons newspaper as a compositor. A lover of music and the theater, Horace learned to play the flute, a talent he continued to foster throughout his life. In 1843, soon after being ordained an elder by Joseph Smith, he served a mission to the east with Amasa Lyman. Upon his return to Nauvoo, he began thinking seriously about a future companion. Who better, perhaps, than his childhood friend and sweetheart, Helen Mar Kimball? But courting Helen Mar would pose serious unforeseen difficulties, and marrying her would come at a most unusual cost.

Helen Mar Kimball

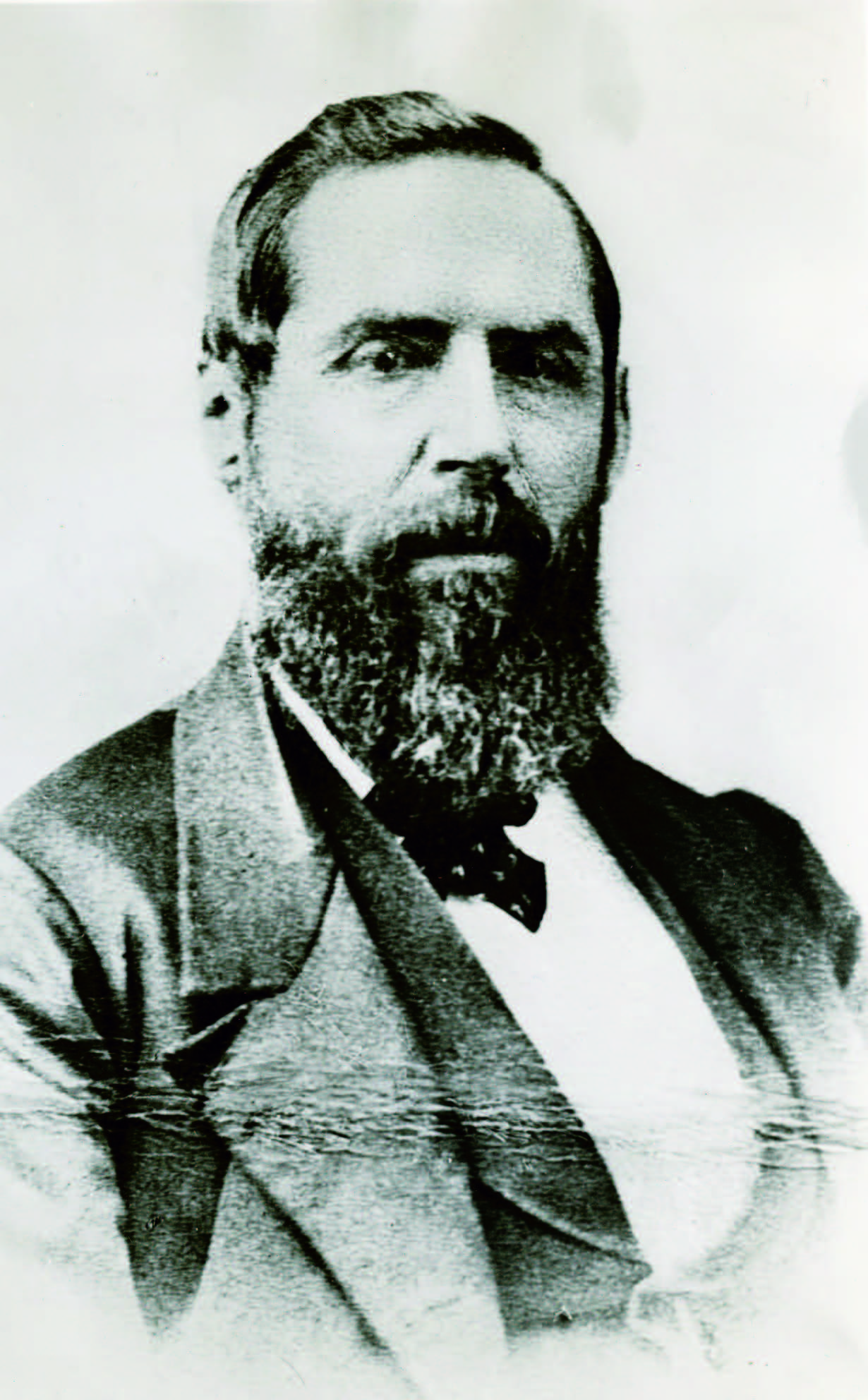

Horace K. Whitney (1823–84). Courtesy of Church History Library.

Horace K. Whitney (1823–84). Courtesy of Church History Library.

Helen Mar Kimball was born in Mendon, Monroe County, New York, ten miles west of Palmyra, on 22 August 1828, the fourth child and oldest daughter of Heber Chase and Vilate Murray Kimball. Her parents converted to Mormonism in April 1832 and removed to Kirtland in the fall of 1833, when she was but five years old. Her father, totally devoted to the cause and a hardworking farmer, potter, and blacksmith, had traveled with Joseph Smith on the Zion’s Camp expedition of 1834 to Jackson County, Missouri. His unswerving commitment to the Mormon prophet led to him being called as one of the original Twelve Apostles in February 1835. He would later serve in the First Presidency of Brigham Young for more than thirty years. In the spring of 1836, Helen Mar attended Eliza R. Snow’s school in a house connected to Joseph Smith’s dwelling, where she remembered using the Book of Mormon as a textbook. “Uncle” Brigham Young, a very close friend of the Kimballs, baptized her a member of the church in the frozen Chagrin River in 1837, cutting a hole in the ice to perform the ordinance. Unbothered by the cold water, she said of it later, “I had longed for this privilege and though I had some distance to walk in my wet clothes I felt no cold or inconvenience from it.”[9]

When her parents decided to move west to Missouri, “I was delighted,” she remembered, “although some of my little mates tried to frighten me with awful tales about being eaten alive by the Missourians, who were cannibals with horns.”[10] Very much like her father in faith and disposition, she was seen by many as his “best representative.” Shortly thereafter, nine-year-old Helen Mar left for Missouri with her parents, arriving in Far West on 25 July 1838. Unfortunately, they arrived in a hurricane of persecution. Six months later, the Kimballs fled for their lives, along with thousands of other Saints, to Illinois, settling first in Atlas, Illinois, later in Quincy, and finally in Commerce (Nauvoo), arriving there in the summer of 1839.

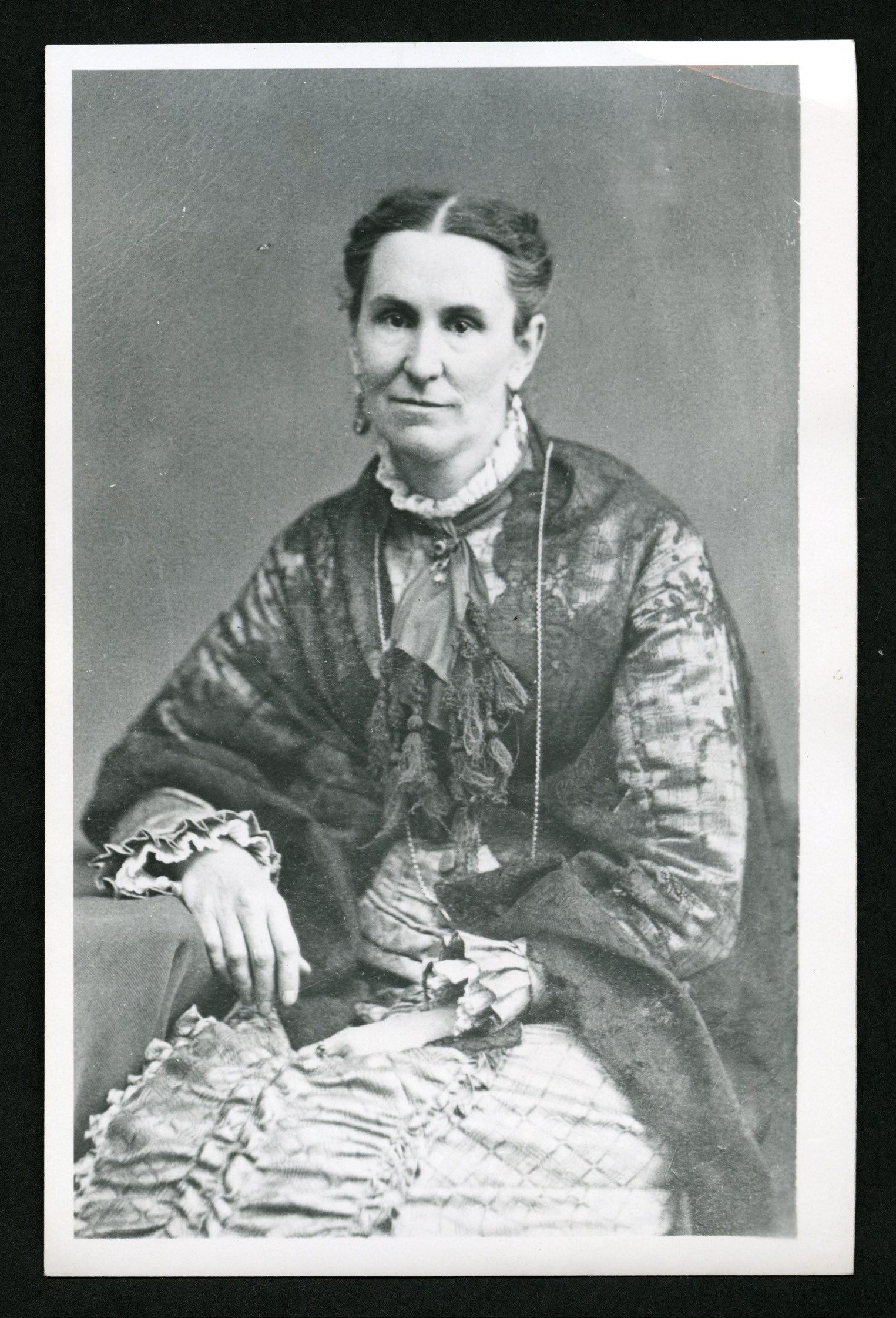

Helen Mar Kimball Whitney (1823–96). Courtesy of Church History Library.

Helen Mar Kimball Whitney (1823–96). Courtesy of Church History Library.

Life in Nauvoo was never easy. Her father, Heber, was soon called on a mission to Great Britain, leaving his family behind for eighteen months. The success of that apostolic mission led to thousands of new British converts eventually migrating to Zion.[11] That remarkable achievement, nevertheless, must be weighed against the sufferings and deprivations of family loved ones and “church widows” left behind. Although Heber built a primitive log home upon arriving from Quincy and a newer house just before he left for England, life in Nauvoo ever proved challenging and unpredictable. Although Joseph Smith called their city “Nauvoo the Beautiful,” he later said it was at first “a deadly sickly hole,” and, while painting as bright a picture as possible for would-be emigrants, he admitted that “although we have been keeping up appearances, and holding out inducements to encourage immigration, that we scarcely think justifiable in consequence of the mortality that almost invariably awaits those who come from far distant parts.”[12] Many sickened and died from malaria, ague, and other diseases. Money was always scarce; food, shoes, and clothing were in short supply; and visitors were not always sensitive. Helen remembers receiving two toy china dolls from her father as a gift, which she put on salt cellars for display. When Joseph Smith dropped by one day to visit the family, he accidentally broke the head off one of them and merely remarked, “‘As that has fallen, so shall the heathen gods fall.’ I stood there a silent observer, unable to understand or appreciate the prophetic words, but thought them a rather weak apology for breaking my doll’s head off.” [13]

The Prophet came by for another reason when Helen was but fourteen years old. It is a well-established fact in Mormon history that Joseph Smith claimed to have received a revelation as early as 1831 on the eternality, as well as the plurality, of the marriage covenant under certain prescribed conditions. Fearing resistance and a harmful backlash if publicly announced, he had introduced the “principle” of plural marriage in secret difficulty and deft denial.[14] Evidence suggests that he took his first plural wife, Fanny Alger, in 1835. And well before he informed his first wife, Emma, he also had married Louisa Beaman, his first plural wife in Nauvoo, in April 1841.[15] That same month, he also married nineteen-year-old Emily and twenty-two-year-old Eliza Partridge, two sisters whom Emma may have given to her husband in marriage. By that time, Joseph Smith had already married as many as eighteen other women. In all, he may have married as many as thirty women, some for “time” and others for “time and eternity.”[16] His brother Hyrum was at first a reluctant believer in the practice, but eventually, he also accepted it, marrying at least three women. Wanting to support her husband but unwilling to share his affections with other wives, Emma found polygamy to be “an excruciating ordeal.” She not only “vacillated” in her support of it but eventually denied that her husband had ever countenanced the practice. The intensely difficult matter of plural marriage contributed to her decision not to go west with the Saints in 1846 and in significant ways contributed to the establishment of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in 1860.[17]

Newel K. Whitney store, Kirtland, Ohio, circa 1907. Photograph by George Edward

Newel K. Whitney store, Kirtland, Ohio, circa 1907. Photograph by George Edward

Anderson. Courtesy of Church History Library. Original in the George Edward Anderson

Collection, Brigham Young University.

The Prophet also instructed several others to enter quietly into the practice, although to speak little if anything about it, with most plural marriages performed in private homes. One of the first was Helen’s own father, Heber C. Kimball. In early 1842 he married two spinster sisters, Laura Pitkin and Abigail Pitkin, both of whom were friends of the family, and soon afterwards the much younger Sarah Peak (Noon). [18] Vilate, Heber’s original wife and devoted follower of the Prophet, after struggling with the principle, is on record as receiving a revelation dispelling her doubts and encouraging her not only to accept but also to promote plural marriage. Heber was eventually sealed to at least forty-three women before he died in 1868, with children from seventeen of them. Still, according to his biographer, “It was always Vilate who remained the center of his emotional life.”[19]

Meanwhile, underscoring the secrecy of the practice, when Sarah Peak had a child in December 1842 (or early January 1843), Helen, who was now her stepdaughter, “had no knowledge then of the plural order,” as she later recorded, “and therefore remained ignorant of our relationship to each other until after his [the infant’s] death, as he only lived a few months. It’s true I had noticed the great interest taken by my parents in behalf of Sister Noon [Peak] but . . . I thought nothing strange of this.” [20]

Kirtland Temple, circa 1907. Photograph by George Edward Anderson. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Kirtland Temple, circa 1907. Photograph by George Edward Anderson. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Then on 27 July 1842, Bishop Newel K. Whitney and Elizabeth Ann gave their seventeen-year-old daughter, Sarah Ann Whitney, Horace’s younger sister, to Joseph Smith in yet another plural marriage, with her father, Bishop Whitney, performing the ceremony and her mother standing by. “They willingly gave to him their daughter,” said Helen of this event, “which was the strongest proof that they could possibly give of their faith and confidence in him as a true Prophet of God.”[21]

Horace, however, was not so impressed. Though he soon afterwards accepted the call to serve a short-term mission east with Amasa Lyman, he remained unreconciled to the matter until later. According to Helen, “He had some slight suspicion that the stories about Joseph were not all without foundations, but had never told them, nor did he know the facts till after his return to Nauvoo, when Sarah hastened to tell him all. It was no small stumbling-block to him.”[22]

Twenty-five sons and daughters of Heber C. Kimball, 14 June 1887. Helen Mar Whitney, middle row, fourth

Twenty-five sons and daughters of Heber C. Kimball, 14 June 1887. Helen Mar Whitney, middle row, fourth

from left. Courtesy of Church History Library.

In May 1843, Helen Mar Kimball was two or three months shy of her fifteenth birthday when Joseph Smith approached her parents seeking permission to marry their daughter. Anxious to have his family sealed to that of the Prophet’s, Heber encouraged his daughter to accept the proposition. Astounded, Helen vacillated for the next twenty-four hours. “I was skeptical—one minute believed, then doubted,” she later wrote. “I thought of the love and tenderness that he felt for his only daughter, and I knew that he would not cast her off, and this was the only convincing proof that I had of its being right. I knew that he loved me too well to teach me anything that was not strictly pure, virtuous and exalting in its tendencies; and no one else could have influenced me at that time or brought me to accept of a doctrine so utterly repugnant and so contrary to all of our former ideas and traditions.”[23] In what might be termed a “dynastic” sealing between two of the most prominent families in early Mormonism, the Smith and Kimball houses would now be eternally linked together. Nevertheless, it almost broke her mother’s heart. “She had witnessed the sufferings of others, who were older & who better understood the step they were taking,” Helen later recalled. “& to see her child, who had scarcely seen her fifteenth summer, following in the same thorny path, in her mind she saw the misery which was as sure to come as the sun was to rise and set: but it was all hidden from me.”[24]

Daguerreotype of the Nauvoo Temple, ca. 1847, photographed by Louis R. Chaffin. Original in the Cedar City

Daguerreotype of the Nauvoo Temple, ca. 1847, photographed by Louis R. Chaffin. Original in the Cedar City

Daughters of Utah Pioneers Museum. Used with permission.

With Joseph Smith’s death in June 1844, Helen became a very young widow without child, sealed for eternity to the Prophet but with a full life ahead of her. Horace was then twenty years old and looking for a companion. The two began dating and, putting all their doubts, questions, and misgivings aside, made plans to marry—eventually. Their courtship may have been shortened by circumstance, but they had long recognized they had much in common—by faith, interests, and disposition. And theirs was more than a platonic relationship. In one of his letters written somewhere along the Mormon Trail in Nebraska, Horace remembered some of those quieter, more intimate times: “I think of you all the time, and God knows, that my thoughts are frequently wafted home to the old chapel fireside, when we so much enjoyed each other’s society at eventide.”[25] However, the intense persecution surrounding the Saints in Nauvoo in late 1845 and the decision of church leaders to leave Nauvoo sooner rather than later led them to move quickly. Better to be married during the harrowing journey west, they figured, than to try to find one another in an unknown somewhere in the wilderness. Helen received her endowment on New Year’s Day 1846, and on 3 February, just one day before the commotion of the Mormon exodus began, she and Horace went to the not-yet-dedicated Nauvoo Temple to exchange vows on their very special day.

What happened next was a strange twist. On their wedding day, Helen was sealed to Joseph Smith for eternity, with Horace standing proxy for the Prophet; then Horace and Helen were sealed together for time. The next day, Helen stood proxy as Horace was sealed to an Elizabeth Sykes, deceased. Todd Compton, in his book on Joseph Smith’s many wives, refers to this as a “wistful sadness,” a “bittersweet, paradoxical marriage” for young sweethearts that would go through life expecting to spend eternity with other companions.[26]

Tithing Office, Salt Lake City, 1861. Charles W. Carter Collection,

Tithing Office, Salt Lake City, 1861. Charles W. Carter Collection,

Church History Library.

One would err, however, in concluding that their marriage for time would be an unhappy one. As Helen wrote in a short autobiography, “I loved and married your father. . . . We have lived happily together for over 35 years.”[27] And despite the fact that they lost their first three children to the rigors of the exodus, they would have eight more. A staunch believer in the sanctity of plural marriage, Helen encouraged her husband, Horace, to take other wives, which he did. Nonetheless, Horace was never a strong supporter of polygamy. He obeyed it out of his enduring devotion to the Prophet Joseph but did so reluctantly. Like his father-in-law’s marriage to Vilate, his first wife was preeminent. “You will always be the one, and the only one to whom I shall resort to pour out my griefs,” he wrote in April 1849, “and from whom I shall expect that consolation which man sometimes stands in need of, and which can only be administered with effect by a dutiful and affectionate companion, which you have always proved yourself to be. . . . As long as you are mine, Helen, you shall continue to stand at the head.”[28]

Departing Nauvoo in the vanguard company of the Twelve, and as their writings will attest, their honeymoon was more of a “honeymud,” as they and their fellow Saints crossed Iowa together, victims of one of the wettest springs on record. Taken together, Horace’s daily journal entries and Helen’s reflective commentaries bring to life the love they shared one for another, their mutual faith in God and in Mormonism, and their hope for a new life with fellow believers in a new home “far away in the West.”

In the years following their arrival in the Salt Lake Valley—Horace with the Brigham Young company of the Twelve in July 1847, and Helen in 1848, after Horace had visited Winter Quarters in the fall of ’47—the two went on to live a happy married life. Horace worked as a clerk in the Tithing Office for twenty years. To augment his meager income, he also worked as one of the original compositors for the church-owned Deseret News, beginning in 1853. He fostered his love for music and the theater by becoming a member of various bands and orchestras and by serving as an officer in the Deseret Dramatic Association. He also served a second mission for the church, this one back to the Ohio of his childhood, in 1869–70. Ever faithful to the church, he once penned the following: “My intention is to live humbly and prayerfully, bear a faithful testimony to the truth, and in all things honorably acquit myself before God and man.”[29] Horace Whitney at least two other women–including Lucy Amelia Bloxham in 1850, by whom he had one child; and Mary Cravath in 1856. He successfully passed that legacy of faith on to his children, one of whom, Orson F. Whitney, himself a very gifted writer and speaker, served twenty-nine years in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, from 1906 to 1935. Horace died in Salt Lake City on 22 November 1884 at age sixty-one.

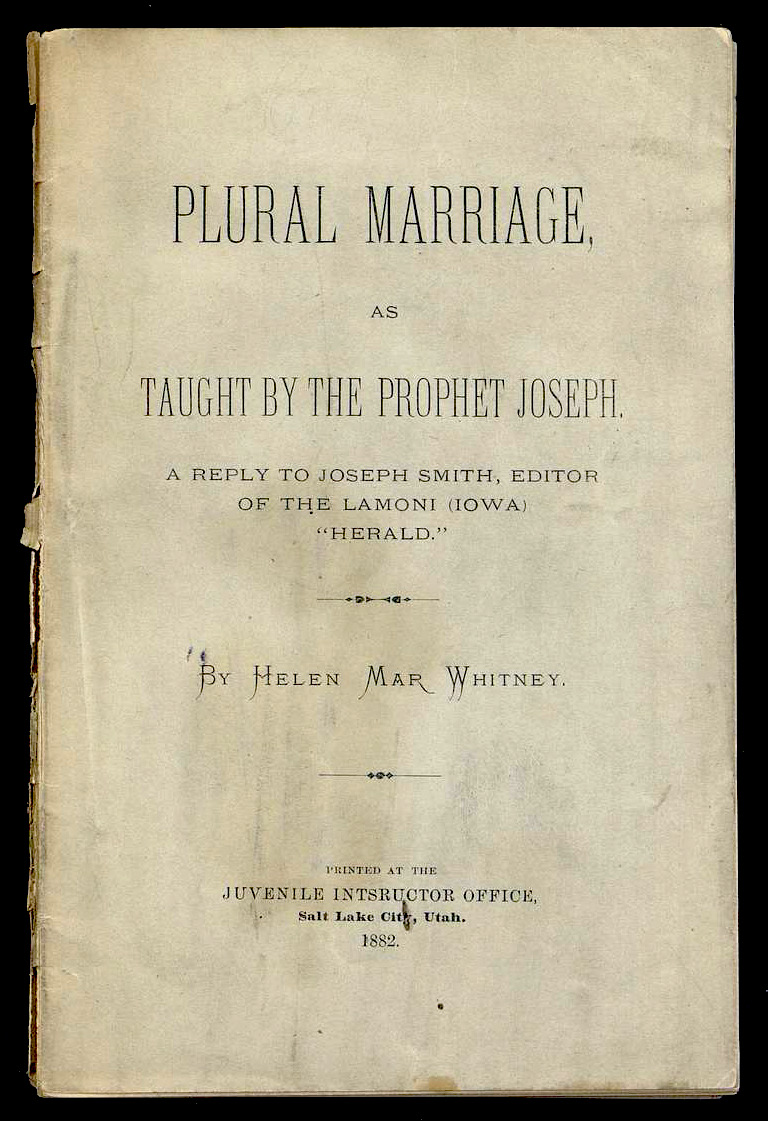

Helen Mar Whitney, Plural Marriage as Taught by the

Helen Mar Whitney, Plural Marriage as Taught by the

Prophet Joseph. Church History Library.

Helen Mar lived on to publish a series of reminiscences of the Mormon exodus in her later life in the Woman’s Exponent, a literary magazine aimed at the Mormon female audience, that constitutes a fine complement to her husband’s diaries. Together, these two records form one of the most comprehensive records of the Mormon exodus extant and certainly the best husband–wife account available. She also published two booklets in defense of polygamy and of her teenage marriage to Joseph Smith.[30] Concerning her defense of plural marriage, she later wrote: “It was to be a life-sacrifice for the sake of an everlasting glory and exaltation,” a principle “calculated to purify and exalt the human family.”[31] And, speaking of her own teenage marriage to the Prophet and of those many women who married Joseph Smith, she wrote the following late in her life: “We may read the history of martyrs and mighty conquerors, and of many great and good men and women, but that of the noble women and fair daughters of Zion, whose faith in the promises of Israel’s God enabled them to triumph over self and obey His higher law, and assist His servants to establish it upon the earth, though buried in the past, I feel sure there was kept by the angels an account of their works which will yet be found in the records of eternity, written in letters of gold.”[32] Faithful to the Latter-day Saint cause, Helen Mar died in Salt Lake City a half century later, on 15 November 1896, twelve years after the death of her husband, and six years after President Wilford Woodruff’s Manifesto signaling an end to the Mormon practice of polygamy.

Scope

Returning now to the larger story of the Mormon exodus of 1846–47, it might be helpful to view it in its five distinct phases:

1. Departure from Nauvoo, Illinois, and the crossing of Iowa Territory, February–August 1846

2. Winter Quarters (Nebraska) settlement, fall 1846–spring 1847 (and later in Kanesville, Iowa, just across the Missouri River)

3. Vanguard company journey of the original Mormon pioneers under the direction of Brigham Young from the Missouri River Valley to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake, 1 April–24 July 1847

4. Original summer settlement in the Salt Lake Valley, complete with the building of fortifications, planting crops, and establishing colonization priorities, 25 July–31 August 1847

5. Return trip of the company of the Twelve Apostles and other church leaders from the Salt Lake Valley back to Winter Quarters, late August–31 October 1847

Several excellent journals have been published over the years that document this exciting chapter in Mormon history, including those of Thomas Bullock, William Clayton, Orson Pratt, Hosea Stout, Howard Egan, Norton Jacob, and Wilford Woodruff. Each has its own unique strengths and limitations. It is in comparison to these journals that the writings of Horace K. Whitney and Helen Mar take on special significance. Most of these pioneer journals cover only portions of the Mormon exodus as diagramed below.

| Diarists | Segments (taken from the above five distinct parts) | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Thomas Bullock | x | x | x | ||

| Wilford Woodruff | x | x | x | ||

| Hosea Stout | x | x | |||

| Orson Pratt | x | x | x | ||

| William Clayton | x | x | x | x | x |

| Norton Jacob | x | x | x | x | x |

| Howard Egan | x | x | x | ||

| Horace K. Whitney | x | x | x | x | x |

In contrast, the Whitney journals cover all five segments and provide a very complete account of the entire story. When Helen Mar’s reminiscences are included, they provide not only a woman’s essential perspective but a very personal, very faithful view as well. And although it is true that her reflections have twice before been published, never have they been so carefully aligned, as they are herein, to the everyday life on the Mormon Trail.[33] His and her writings are wonderfully synergetic, revealing, and supportive, and, when read in tandem one with another, like looking through a pair of binoculars, they clarify the many stories of the exodus, illuminate our understanding, and provide focus and a fuller, clearer, and more correct viewing of this important moment in time.

Phase 1: Crossing Iowa

Everything was supposed to happen in 1846.[34] The vanguard companies of approximately 2,500 left Nauvoo in early February 1846. The original plan was to cross Iowa in four to six weeks, get across the Missouri river, and then for Brigham Young and a handpicked number of the best pioneers to head west and find a suitable valley somewhere in “the tops of the Rocky Mountains.” However, “Brother Brigham” might have been able to escape his enemies but he could never get away from his people. At one point, in exasperation he said to his followers who were afraid of being left behind:

The Saints have crowded on us all the while, and have completely tied our hands by importuning and saying: Do not leave us behind. Wherever you go, we want to go, be with you, and thus our hands and feet have been bound which has caused our delay to the present time, and now hundreds at Nauvoo are continually praying . . . that they may overtake us and be with us. . . . They are afraid to let us go on and leave them behind, forgetting that they have covenanted to help the poor away at the sacrifice of all their property.[35]

This matter of covenant points to the fact that the Latter-day Saint leaders saw their exodus as an extension of the law of consecration and that if they lived in obedience to that promise, all would go well. However, such crowding, delays, and insufferable heavy rains during that spring of 1846 impeded their progress. Hundreds were left back at Garden Grove and Mount Pisgah, their hastily erected way stations in Iowa Territory that they established to preserve their health and strength and to put in crops for the thousands yet to follow. As a result, instead of crossing Iowa in four to six weeks, it took them three months! When Brigham Young and his advance company finally reached the Missouri on 14 June 1846, it was all but too late to make a dash for the Rockies.

Whitney’s journal attests abundantly to the trials and travails of crossing Iowa. Writing on 11 April, he noted the following: “Some of my fathers’ teams got stuck in the mud, and had to stop a mile or two back and none reached us except J. C. K[ingsbury] with the buggy, the one horse wagon, and Sarah Ann’s wagon. Bro. Pond broke his harness in attempting to extricate himself from a mud-hole.” Upon reaching the Grand River on 1 May, he wrote this entry: “The weather has been so inclement since our arrival that our stay here will necessarily be protracted beyond the time originally intended.” Whitney not only speaks corroboratively of their well-known troubles crossing Iowa but likewise offers a farmhand’s observations into the building of both Garden Grove and Mount Pisgah, insights not always afforded by other diarists. For instance, the following is his description of the early days at Garden Grove: “There are a hundred men assigned to this business, 10 laying up rails, 48 to building houses, 12 to each house – 10 herding cattle, 12 digging wells, 10 building a bridge across the river for to pass over on our journey west, 10 stocking ploughs and making drays, 5 or 6 blacksmith shops started, the remainder to attend to the business of farming, etc. etc.”[36]

Phase 2. Winter Quarters, September 1846–April 1847

Horace’s and Helen’s writings reflect the fresh vantage point of a young, highly committed Mormon pioneer couple, which lends a unique spirit of anticipation and faith to their observations. Contrasted with some other journals—like the writings of Hosea Stout, which tend to be critical, suspicious, and dark—the Whitneys wrote with a certain youthful alacrity.[37] Nevertheless, his writing style and sense of detail ofttimes are of the mundane, everyday variety, often lacking the emotion of the moment, a dimension his wife often added to complete the story.

Their insights are particularly revealing about the trying and very difficult Winter Quarters segment of the exodus, that period extending from the fall of 1846 until April the following year. The Saints’ first priority was planting spring crops, hay cropping, branding, and otherwise taking care of the thousands of head of cattle and sheep that were mostly confined in the “rush bottoms” some hundred miles upriver. They then turned their attention to fashioning crude living quarters. More than any other observer, explains how they survived that difficult winter. He informs us on what cabins they built, how they were constructed, how they were aligned throughout their makeshift community, and much more pertaining to the social life of their new city. While many passed the fall and early winter living in tents with wind-torn canvases, in caves dug out of the side of the Missouri riverbanks, or in wagons exposed to the elements, Horace speaks of the tireless energy required to build lifesaving, if hastily erected, cabins for as many as possible: “Saturday the 7th: Fine day. Engaged in roofing and sodding the second house into one room of which we [he and wife, Helen Mar] moved this evening, the other room being occupied by Sister Kimball [his mother-in-law] and Mary Kimball. We congratulated ourselves considerably upon being able to live in a house once again, as we have got thoroughly tired of living in tents.”[38]

His journals also speak of digging thirty-five-feet-deep wells and building, chinking, and daubing dozens of hastily built log cabins, often one or more in a day or two, each five to seven feet high with sod chimneys, tent awnings supporting dirt-covered roofs with freshly cut wooden shingles, and dirt floors. They erected their cabins very close to each other and in a “compact body” so that they might be “better able to defend ourselves against [Indian] encroachments.”[39]

These lodgings were not only drafty and often cold; they were not always the safest things to live in. “This evening a fire was discovered under the hearth in Bro. K[imball]’s room,” Horace recorded in January 1847. “We took down the better part of the chimney in order to get at the fire, which we put out, and rebuilt the chimney, this taking till half past 4 in the morning. Bro. K. felt very thankful that the fire did not occur in the night when we were all asleep, as there was 5 or 6 lbs of powder in a chest near the fire place, in addition to the danger incurred by the fire otherwise.”[40]

Horace likewise provides us with much information on the construction of the Winter Quarters Council House, which, much like the Newel K. Whitney store back in Kirtland, Ohio, would serve as the mercantile establishment and central gathering place for the Mormon settlement. Highly frugal in his own personal expenditures, Horace gives more financial details than most other diarists, complete with costs and expenditures. Such information allows us to reconstruct and understand the Winter Quarters economy.

He also describes the many dances, balls, and festive occasions that the Mormons held during that winter, as if to defy and stave off the darkness and sadness of that fateful time. A member of the Nauvoo brass band that had now been revived in Winter Quarters, Whitney also tells of one round of parties after another, whether with the bishops charged with taking care of the wives of the Mormon Battalion, the quorums of high priests, the “Silver Greys” of older folks, or some other group. “Ellis Eames, a player on the violin, came up from the Point [Council Point],” he recorded on 1 March 1847. “A number of [the] Band including him and myself went round in a sleigh this evening, (Porter driving) and serenaded several places in the town. Bro. K. was along with us. We stopt at Bishop Hunter’s and played a tune and then by invitation of Bro. K., went to his house, where we spent some time in dancing, etc. and retired.” [41]

Yet Horace and Helen Whitney were not oblivious to the sufferings and agonies of many around them that fateful winter. Sometimes referred to as Mormonism’s Valley Forge, the Latter-day Saints’ stay at the Missouri River in the winter of 1846–47 was a testing point of faith. William Clayton’s hymn of sacrifice and endurance—“Come, Come, Ye Saints”—spoke of holding on despite every challenge. This prairie anthem of the exodus said in part, “And should we die before our journey’s through, happy day! All is well!”—a foreboding of worse times to come. Because of their long exposure to the elements, their poor and substandard housing once they reached the Missouri, and the outbreak of such deadly diseases as malaria and scurvy, the Mormons began to perish in epidemic numbers. At least 1,200 died (one in ten) within two years of their arrival at Council Bluffs. These were frightening times among a people who believed they were on God’s errand. And Horce speaks much about it, although without criticism, rancor, or disbelief. His accounts of life at Winter Quarters are incomparably rich and detailed and unbelievably positive for such a dire moment, striking a tone of deliberate faithfulness in their furnace of affliction.

A good example of this is his characteristically matter-of-fact entry in October 1846:

Commenced raining this afternoon. . . . Forgot to mention that Eliza Ann Pierson, a niece of Dr. Willard [Richards] died last evening at his tent. She had left father and mother far behind, to join the saints of God in the wilderness, to suffer and die among them for the gospel’s sake. She was a worthy, exemplary young person, and the remembrance of the many happy hours I have passed in her society, together with her sisters and friends, will never be obliterated, while time shall last. She was from Richmond, Massachusetts, where I became acquainted with her during my sojourn in the E[eastern] States.

Not content to dwell on such sadness, he ends his entry thus: “This afternoon the brethren drove into camp all the cattle they found during their search yesterday which covered a large space of ground.”[42]

Indeed, most of his entries are as cheerful and upbeat as they are contemporary in the sense that they were usually recorded the day, or the day after, the events occurred. For example, in the midst of profound sickness, serious privations, and enormously hard work, Horace continuously sees the positive as indicated in the following entry: “William, Porter and myself took a walk around the city [Winter Quarters] this afternoon, the first time that we three have had a social walk and ‘chat’, since we left the city of Nauvoo. There seems to be a particular dispensation of Providence in our behalf; for although, we have had several cold nights and frosty ones, the weather had been remarkably mild for winter, and we have not, as yet, experienced the first snow storm.” [43] This silver lining descriptive approach, written at a time when they knew so many were perishing, permeates much of his descriptions.

Writing in December 1846, Horace makes reference without elaboration to the tragedy that struck Stillman Pond, who eventually lost his wife and four children: “Rather cool today. Today Abigail Pond died, her two sisters, Harriet and Jane died a day or two ago.”[44] Writing months later of a time when hundreds of others had perished, he records: “Fine day. Nothing of importance to-day. . . . There is a disease, called by the folks here, the ‘black-leg,’ getting quite prevalent in the camp. It commences with a sharp pain in the ankles, swells, and finally the leg gets almost black, and in many cases it proves fatal. There have a great many died, within the last month. It is caused, in a great measure, by the want of vegetable food, and having to eat salt food.”[45]

Thus Horace takes time to mention the sad and the sorrowful but never gives into it or provides it undue time or space. While we may regret the lack of intense emotion in his diaries, one senses from them a sheer determination not to surrender to the darkness and discouragements closing in around them. Their everyday efforts at survival drive from off the page any lengthy gloomy ruminations of how bad things had become.

Phase 3: To the Valley of the Great Salt Lake, April–July 1847

Horace Whitney’s fascination with the American Indian is well covered in his accounts. These include the Otoe, Omaha, Ponca, Pottawattamie, Pawnee, Sioux, Shoshone, and Ute tribes. He speaks in a fair-minded way of their habits, tribal warfare, trading practices, lodgings, hunting patterns, fears, and frustrations. Occasionally, he writes of how they were mistreated and misunderstood by others. For example, the following entry tells of the government payments made for certain Indian land properties at the Missouri.

Bro. C. [Layton] informs me he never saw such a swindling operation as that practiced on the Indians down there, they receiving their payments in money and then followed by a gang of sharpers who watch their opportunity, get them drunk and then gamble with them and cheat them out all their money. Bro. John Kay came down here from the Punkaw [Ponca] nation. He has been out with them hunting since he left here and will rejoin them in 6 weeks from this time.[46]

And then there is this very sad observation:

This evening, the [Omaha] Indians encamped near Brigham’s, had a great powwow among them, screeching and yelling in a horrible manner on account of their having just received intelligence that a large number of their warriors, who went on the hunting expedition a short time since, having been killed off by the Sioux.[47]

A member of Brigham Young’s 148 handpicked pioneers who left Winter Quarters in April 1847, Horace constantly tells of their encounters with other tribes. For instance, their deliberate calculation to make their own trail on the north side of the Platte rather than to follow the California and Oregon Trail on the south side brought them square into Pawnee country and right through the heart of the Pawnee Indian villages. The belief was that it was better to make peace with them up front. Writing in late April near the Pawnee Indian villages on the north side of the Platte, he records: “Pres’t Young . . . said that if we had an attack from Indians, it would be from the Sioux, not the Pawnees, for the latter knew that the former were in the country and were watching them – that the Sioux when they came to make an attack, always [down] a little ravine that lies north-east of us.” [48]

Horace describes what he saw upon reaching the Pawnee village: “Orson and myself went and took a view of the ruins of the Pawnee village which was an interesting sight, indeed, and gave me singular feelings. The village is situated on the northern bank of and immediately fronting the river – it is irregularly formed, or laid out, is 1¼ a mile in extent and comprised upwards of 200 lodges, a great share of which have been burnt down by the Sioux.” [49] One reason the Mormons brought a cannon with them was to scare off possible Indian attacks, attacks that never came.

All across Nebraska and Wyoming, Horace offers daily insights on the weather, the Platte River, buffalo—“the plain is perfectly black with them”—and their many hunting expeditions, accidents along the trail, camp life, Sunday sermons, daily mileages, and multiple creek and river crossings. As with the authors of most other overland trail journals, he is impressed with the changing topography and gives ample attention to such trail landmarks as Ash Hollow, Chimney Rock (which they reached in late May), Scott’s Bluff, Fort Laramie, Independence Rock, South Pass, Fort Bridger, and ultimately the Salt Lake Valley.

His journals are unexceptional in their daily accounts. The Orson Pratt and William Clayton journals are more explicit and more exciting in this regard. The major contribution of Horace’s journals is providing us with an understanding of the organization of the companies of the Saints and the doctrinal underpinnings surrounding it. Although not the official clerk of any of the pioneer companies, young Horace K. Whitney, as the son of Presiding Bishop Newel K. Whitney, was a trusted secretary to Brigham Young and knew well the inner operations of the church. Though still young, Horace was tasked by Brigham Young and other prominent leaders to keep their records, provide secretarial services, and record carefully and legibly the comings and goings of the Saints. For instance, it was Horace who recorded Joseph Smith’s revelation on eternal/

Another deficiency of Horace’s journals is that, unlike the Wilford Woodruff journals, they are not generally given to spiritual ruminations. As a young husband, laborer, sheepherder, and all-around construction worker, Horace is much closer to the hands-on, basic everyday survival activities of the camps. These routine but essential duties included herding sheep and cattle, working with the various Indian tribes, hunting and fishing, putting in crops and successfully establishing the new Salt Lake settlement in the summer of 1847, and undertaking a myriad of other life-sustaining responsibilities. Helen Mar’s reminiscences often provide the spiritual flavor and perspective that her husband’s daily recordings sometimes miss.

Yet the careful observer will also see much more in his journals than merely descriptions of the physical. Carefully tucked away within them are keys to a remarkable understanding of unique Mormon doctrines and practices as they were beginning to play out on the outer edges of the great American wilderness. As mentioned above, Joseph Smith had introduced the concept of the eternality of the marriage covenant shortly before his death in 1844 and along with it the practice of “celestial” or plural marriage. Not nearly so well understood was the “law of adoption,” also revealed in Nauvoo and played out here along the Mormon Trail.[50]

This principle had both a doctrinal and a social application. The doctrine of the law of adoption based itself upon the belief that salvation in the next life was partly dependent upon one’s actions in this sphere. These included being “sealed” to someone who held the power or priesthood of God and more specifically to someone who held such priesthood “keys” and authorities. And as with their trek west, which demanded the consecration and cooperation of everyone working together in camp, the Latter-day Saint view of salvation was arguably less an individual concern and more a group or family matter. As they wended their way west, it was, as William Clayton reminded them in his song, always a matter of “we’ll find the place” and of “should we die” rather than going it alone. Either they make it in the company of others in this life or in the next, or they do not.

The law of adoption was an early expression of this group salvation concept. The uniquely Mormon doctrine of baptisms for the dead, practiced in Nauvoo since 1841, was based upon the belief that families must somehow be “linked” together in one great family chain extending back into the mists of earthly time and that such extended and extensive earthly families could be welded together by priesthood authority and ordinances hereafter. As Joseph Smith’s revelations put it: “The earth will be smitten with a curse unless there is a welding link of some kind or other between the [ancestral] fathers and the children, upon some subject or other—and behold what is that subject? It is the baptism for the dead” (D&C 128:18). To speak of baptisms for the dead without intergenerational family sealings is to miss a critical point of their belief.

A problem in this developing doctrine of salvation at this very early formative time was that deceased ancestors and ancestral families had died and gone on without the saving power of the priesthood. To be sealed to a man who had not the gospel in his life and who had never received the priesthood was not yet clear or convincing in Mormon thinking. In fact, it would not be until 1877 in the St. George (Utah) Temple that endowments for the dead and multigenerational family sealings began.[51] Until then, the Saints’ understanding was that they should be sealed or “adopted” into priesthood families, represented best by church leaders or general authorities, living or dead.

The essential thing was for the male head of the family—and his plural marriage wives and families—to be sealed or “adopted” to those priesthood leaders over him who held the keys of authority and eternal life in a vertical interconnected chain of priesthood-based, assured salvation. The practice of plural marriage, by which additional wives were sealed or married to the same man, was an extension or appendage to this doctrinal understanding, the horizontal branches to the ever-expanding vertical kingdom or tree of family salvation. And for a man to be an adopted son of such a family, or a woman to be sealed through being married, plurally if need be, provided an expectation of a more economically secure living in this world and the assurance of an eternal one hereafter complete with family and friends. Small wonder such practices were of great importance to this growing number of Latter-day Saints, many of whom wondered if they would survive their impending trials.

The practice of the law of adoption also influenced both the social order of the Winter Quarters community as well as its travel patterns. It often dictated social spheres of influence and one’s circle of friends and associates, even the locale of their tents or cabins. One’s place in the family hierarchy provided some kind of social stratification. Those in Brigham Young’s expanding family lived fairly close to one another, as did those in Heber C. Kimball’s family, Wilford Woodruff’s, Willard Richards’s, and those of other prominent church leaders. The expectation was that in return for spiritual blessings and eternal inheritances due from their spiritual fathers, adopted sons and families owed them physical support.

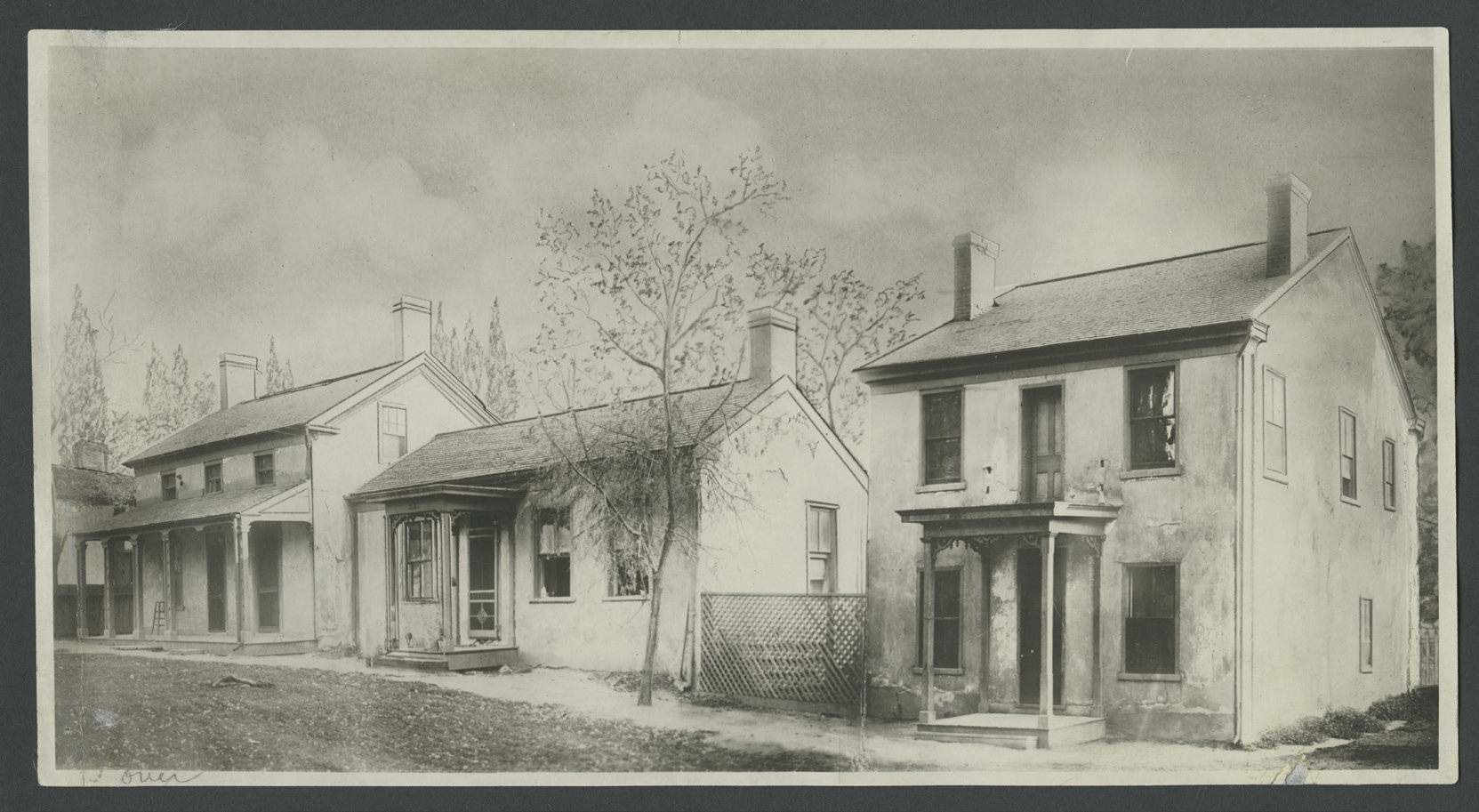

Homes of Horace K. Whitney’s wives (Helen Mar and Mary Cravath) and families, 26 E. North Temple, Salt

Homes of Horace K. Whitney’s wives (Helen Mar and Mary Cravath) and families, 26 E. North Temple, Salt

Lake City. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Occasionally large adopted-family or tribal-family meetings convened in Winter Quarters and along the trail for instructional purposes. Brigham Young remarked as follows in one such meeting:

Those that are adopted into my family . . . I will preside over them throughout all eternity and will stand at their head. Joseph [Smith] will stand at the head of this Church and will be their president, prophet and god to the people in this dispensation. When we locate [in the mountains] I will settle my family down in the order and teach them their duties. They will then have to provide temporal blessings for me instead of my boarding from 40 to 50 persons as I do now, and will administer spiritual blessings for them.[52]

Here, then, is a key reason why the Horace Whitney diaries take on increasing significance. His biological father and presiding bishop over the entire Church, Newel K. Whitney, was an adopted son—in the priesthood lineage sense described above—of apostle Heber C. Kimball, who coincidentally was also the biological father of Horace’s wife, Helen Mar Kimball (Smith) Whitney. Thus he belonged to the Kimball family before being married into it. Horace identifies by name a large number of three or four dozen men and their families who also belonged by the law of adoption to Heber Kimball: Jackson Redding, Asa Davis, Howard Egan, Dan Davis, Ellis Sanders, J. M. Grant, Alfred Randall, to name but a few.[53] He even spent most of one day and part of the next in early January making out a list of the entire Kimball clan.[54] Many of the Kimball family log cabins were erected in close proximity one to another, a Kimball enclave within an already tightly drawn Mormon wilderness community. By extension, the whole of Winter Quarters was “familyized” or “tribalized” in similar fashion. Horace’s diaries, therefore, provide us with a fuller understanding of the complicated social order among the Latter-day Saints and of developing doctrines and practices attendant to the exodus.

The original plan of their travels west was supposed to have followed after this tribal pattern. During wintertime deliberations in mid-January at the newly constructed Council House, Brigham Young drew up plans to have the first company or “division” of one hundred be drawn from his adopted/

In unofficially recording the essence of some of these large adopted family meetings, Horace Whitney provides invaluable insights into the need for such adoptions and the intergenerational linkages they entailed. Said father Heber C. Kimball after listening to comments from his adopted son, presiding bishop Newel K. Whitney:

I have been much edified by the conversation of Brother Whitney, and we always had the same feelings in common and our views always met, and our thoughts flow in the same channel. . . . I am your head, your lawgiver, and king, and will be, to all eternity, and I am responsible to my head and President and you are responsible to me, your file leader. I believe that some of my old progenitors, of whom I have no knowledge, will appear and tell me when the time shall come for me to rise up and administer in the ordinances for them, and I shall receive a great deal of knowledge from them. . . . I want to have power, when I see my brother and sister, to tell Death to depart.[56]

Thus from time to time, whether at Winter Quarters or at various resting places along the trail, Horace and Helen Mar provide profound doctrinal insights into Mormon thought and social practices as they were developing along their way west.

Phase 4: The Salt Lake Valley Settlement, 25 July–31 August 1847

Unfortunately, upon reaching the Salt Lake Valley on 24 July 1847, Horace Whitney says nothing about what Brigham Young may or may not have said when he first saw the future home of the Mormon people. For his part, he writes, “Going down several steep descents, we at length emerged from the pass (having come 4 miles) and were highly gratified with a fine view of the open country and the ‘Great Salt Lake’, whose blue surface could be seen in the distance with a lofty range of mountains in the background.” Not given to hyperbole, Horace stoops to discover something closer by, something that will later come to discomfort the Mormon settlements like little else could. “One thing I omitted to mention, viz. there are numerous black crickets of an enormous size to be seen here.”[57] He does, however, record in early August, just prior to their return to Winter Quarters, that Brigham Young decided that the Salt Lake Valley was indeed the right place to locate their city and to build their temple. Said he: “This is the spot that I had anticipated. They will not have a hard winter here. The highest mountains are near 1¼ miles high. We will find that sugar cane and sweet potatoes will grow here. . . . There never was a better or richer soil than this.”[58]

Reaching the floor of the valley on his twenty-fifth birthday, Horace speaks of the need for immediate irrigation efforts, early scouting expeditions, Brigham Young’s satisfaction with the valley as their “promised land,” edifying sermons in celebration of finding their place, hunting expeditions, floating on the Great Salt Lake, and feverishly planting crops in soil better than they had anticipated—all with the excitement of a young child on a Christmas morn. He also tells of surveying their new city under the direction of Henry G. Sherwood; fencing and building stockades, adobe houses, log cabins, and a bowery; and their first encounters with the Shoshone and Eutaw Indians.

More optimistic than he had been in Winter Quarters, Horace permeates his writings with a spirit of redemption, a promise now fulfilled, a place sought after and now discovered. To that end, he records Heber C. Kimball’s 22 August 1847 sermon in detail: “I wish to God, we had not got to return. If I had my family here, I would give anything I have. This is a Paradise to me. It is one of the most lovely places I ever beheld. I hope none of us will be left to pollute this land.”[59]

Phase 5: Return to Winter Quarters, September–October 1847

But return they must. The account of the return of 108 men, including Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and most of the other leading authorities of the church, is not well documented in most other leading Mormon exodus journals. However, it is a story amply documented in Horace’s writings, as he was among the few directed to return. Leaving the valley on 26 August 1847, the return company made much faster mileage going back than they ever did coming out. Often they covered twenty-two to twenty-eight miles per day, compared to fifteen on the outbound journey. Some reasons for this were their knowledge of the trail, much lighter and fewer wagons, the use of horses rather than oxen, their knowledge of the best camping spots, and shallower creeks and rivers because of the lateness of the season. Among the highlights of their return trip was meeting the so-called Emigrant Camp or “Big Camps” of Mormons heading west under the direction of Parley P. Pratt and John Taylor.

Upon reaching Winter Quarters on 30 October after traveling over two thousand miles over a trackless wilderness, finding a new city and a new hope for the Saints, and enduring privations of almost every kind, the matter-of-fact Horace K. Whitney ended his voluminous journals with the following:

An expression was then taken whether we should all remain in a body, horsemen and all, and go into town together or otherwise; which resulted in the affirmative. Pres’t Young and Bro. Heber then spoke briefly, stating that they were satisfied with the conduct of the Pioneers during the journey of the past season, and blessed them in the name of the Lord; and soon after we were dismissed with the injunction to provide plenty of cotton wood for our horses during the night. Bro. Heber let me have a little flour to-night, as my provisions had all given out.[60]

Conclusion

In summary, the Horace K. Whitney journals and the Helen Mar Whitney reminiscences which accompany them are a two-part history. A young husband–wife duo of writings, they add a freshness and vitality to a well-worn story. While his writings are given more to the nondescript details of everyday living, hers are more of the reflective, ruminating variety. Taken together, they provide remarkably candid insights into the peculiar beliefs, customs, and practices of their people. And, while discussing the negative and the forlorn, they both maintain a cheerful, youthful tone and honest perspective. Combined into one, they are a lasting tribute to those men and women who made so many sacrifices in the cause of their faith and in the hope of a new life “far away in the West.”

Notes

[1] Council of Fifty, Minutes, 4 February 1845, in Matthew J. Grow et al., eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 243.

[2] Nebraska did not become a territory of the United States until 1854, nor a state until 1867. Iowa, on the other hand, became a territory in 1838 and a state in 1846.

[3] Bernard DeVoto, The Year of Decision: 1846 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1943).

[4] Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 23 July 1847, Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Later, on 8 August and as affirmed in the Horace Whitney journals, Brigham Young referred to the Salt Lake Valley specifically when he said, “This is the spot that I had anticipated.” The term “spot,” and more specifically “consecrated spot,” is in consonance with the early revelations of the church referring to Zion in Missouri as the “spot” to build the temple and establish a righteous people” (D&C 57: 3; 84:31).

[5] William Clayton, “Come, Come, Ye Saints,” Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 30.

[6] Joseph Conrad, Youth: A Narrative and Two Other Stories (Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1903), 41.

[7] Horace K. Whitney to Helen Mar Kimball Whitney, 24 December 1869, Helen Mar Kimball Whitney Papers, MSS 179, Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections and Archives Division, Utah State University Logan, UT.

[8] Handwritten memorandum of Horace K. Whitney, 22 November 1840, Helen Mar Kimball Whitney Papers, MSS 179.

[9] Helen Mar Whitney, Woman’s Exponent, vol. 9, no. 22, 15 April 1881, p. 170.

[10] Helen Mar Whitney, Woman’s Exponent, vol. 9, no. 6, 15 August 1880, p. 42.

[11] James B. Allen, Ronald K. Esplin, and David J. Whittaker, Man with a Mission, 1837-1841: The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in the British Isles (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book 1992) See Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green, The Field Is White: Harvest in the Three Counties of England (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017).

[12] Joseph Smith to Horace R. Hotchkiss, 25 August 1841, Church History Library. Don Carlos, Joseph and Emma Smith’s own son, died less than a month later at fourteen months of age.

[13] Helen Mar Whitney, Woman’s Exponent 10, no. 5, 1 August 1881, 34.

[14] Address of Brigham Young, 8 October 1866, Brigham Young Papers, Church History Library.

[15] See the LDS Church website essay on plural marriage entitled “Plural Marriage in Kirtland and Nauvoo,” https://

[16] To date, no solid evidence has been located to indicate that he had any children from any of his plural wives. See Ugo A. Perego, Natalie M. Myers, and Scott R. Woodward, “Reconstructing the Y-Chromosome of Joseph Smith: Genealogical Application,” Journal of Mormon History 31, no. 2 (Summer 2005): 70–88.

[17] At least twenty-nine other men married a total of fifty plural wives in Nauvoo before Joseph’s death. Some scholars have estimated that as many as nine hundred plural marriages were performed in Nauvoo.

[18] Stanley B. Kimball, Heber C. Kimball: Mormon Patriarch and Pioneer (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 95.

[19] Kimball, Heber C. Kimball, 99.

[20] Helen Mar Whitney, Woman’s Exponent, vol. 11, no. 4, 15 July 1882, 26.

[21] Helen Mar Whitney, Woman’s Exponent, vol. 11, no. 19, 1 March 1883, p. 146.

[22] Helen Mar Whitney, Woman’s Exponent, vol. 11, no. 19, 1 March 1883, p. 146.

[23] Helen Mar Whitney, Woman’s Exponent, vol. 11, no. 5, 1 August 1882, p. 39.

[24] Autobiography of Helen Mar Kimball Whitney, 30 March 1881, MS 744, Church History Library.

[25] Horace K. Whitney to Helen Mar Kimball Whitney, 15 April 1847, Helen Mar Kimball Whitney Papers.

[26] Todd Compton, In Sacred Loneliness: The Plural Wives of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1997), 486–87.

[27] Autobiography of Helen Mar Kimball Whitney, 30 March 1881.

[28] Horace K. Whitney to Helen Mar Kimball Whitney, 17 April 1849, Helen Mar Kimball Whitney Papers.

[29] Horace K. Whitney to his family, 26 November 1869, Helen Mar Kimball Whitney Papers.

[30] Helen Mar Whitney, Plural Marriage as Taught by the Prophet Joseph Smith: A Reply to Joseph Smith, Editor of the Lamoni (Iowa) Herald (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1882), and Helen Mar Whitney, Why We Practice Plural Marriage (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1884).

[31] Woman’s Exponent, vol. 9 no. 15, 1 January 1881, p. 114, and vol. 11, no. 19, 1 March 1883, p. 146.

[32] Helen Mar Whitney, Woman’s Exponent, vol. 10, no. 11, 1 November 1881, p. 83.

[33] Helen Mar’s accounts have been published in the Woman’s Exponent and in A Woman’s View: Helen Mar Whitney’s Reminiscences of Church History, ed. Jeni Broberg Holzapfel and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1997). The reminiscences of Helen Mar herein included are selective, not exhaustive, and are included to amplify and illustrate her husband’s journals.

[34] “It being the intention at that time to cross over the Rocky Mountains the same year.” Whitney Journals, 31 March 1846.

[35] Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 3 May 1846 (hereafter Journal History).

[36] Whitney Journals, 27 April 1846.

[37] For the best study of Hosea Stout, see On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout, ed. Juanita Brooks, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1974).

[38] Whitney Journals, 7 November 1846.

[39] Whitney Journals, 13 December 1846.

[40] Whitney Journals, 18 January 1847.

[41] Whitney Journals, 1 March 1847.

[42] Whitney Journals, 11 October 1846.

[43] Whitney Journals, 22 November 1846.

[44] Whitney Journals, 7 December 1846.

[45] Whitney Journals, 18 March 1847.

[46] Whitney Journals, 6 November 1846.

[47] Whitney Journals, 12 December 1846.

[48] Whitney Journals, 22 April 1846.

[49] Whitney Journals, 24 April 1846.

[50] For a good introduction to the law of adoption, see Gordon Irving, “The Law of Adoption: One Phase of the Development of the Mormon Concept of Salvation, 1830–1900,” BYU Studies 14, no. 3 (Spring 1974): 291–314. See also Richard E. Bennett, Mormons at the Missouri, 1846–1852: “And Should We Die” (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987). For the most current study of the topic, see Jonathan A. Stapley, The Power of Godliness: Mormon Liturgy and Cosmology (New York: Oxford, 2018).

[51] For more on this subject, see Richard E. Bennett, “‘Line upon Line, Precept upon Precept’: Revelations on the 1877 Commencement of the Performance of Endowments and Sealings for the Dead,” BYU Studies 44, no. 2 (2005): 38–77.

[52] Journal of John D. Lee, 16 February 1847, as quoted in Bennett, Mormons at the Missouri, 192.

[53] Whitney Journals, 19 October 1846.

[54] Whitney Journals, 1 and 2 January 1847.

[55] Whitney Journals, 18–22 January 1847.

[56] Whitney Journals, 14 February 1847.

[57] Whitney Journals, 24 July 1847.

[58] Whitney Journals, 8 August 1847.

[59] Whitney Journals, 22 August 1847.

[60] Whitney Journals, 30 October 1847.