Milieu of the Martyrs

F. LaMond Tullis, "Milieu of the Martyrs," in Martyrs in Mexico: A Mormon Story of Revolution and Redemption (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2018), 1–18.

“What bravery! They died with their boots on,” remarked one of the Zapatista executioners.[1] He was reflecting almost respectfully on the surreal way that Mormon leaders Rafael Monroy and Vicente Morales had stood to receive the fusillade that pierced their bodies on the evening of 17 July 1915. The terror of facing an execution squad notwithstanding, no cowering, no begging, and no hysterics marred their calm and stalwart resolution to not repudiate their faith. The Zapatista commander had given them that option. The men responded by reaffirming their religious convictions, emphasizing that the only arms they possessed were not the clandestine military weapons they were accused of hiding in the Monroy family store but rather their sacred texts—the Bible and the Book of Mormon—which Monroy carried with him nearly all the time.[2] Monroy was president of the San Marcos Branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Vicente Morales, Monroy’s employee, was also his first counselor.

Whether the slaughterers would have spared the men had Monroy and Morales renounced their faith is now moot. They sealed their fidelity when the executioners fired, when the muzzles of their American-made Winchester M1895 lever-action or Springfield M1903 bolt-action rifles spit out the bullets that silenced their young lives.[3]

Accounts of the executions are copious, ranging from academic treatises to magazine articles, newsprint, films, sound bites, diaries, journals, and family lore, with varying degrees of conformity to the facts, which this monograph attempts to correct.[4] With the centennial of the martyrdoms having arrived in mid-2015, more appeared to be forthcoming, including a new feature-length film.[5] All this notwithstanding, and although the martyrdoms themselves are among the most dramatic events in the history of the Church in Mexico, they had causes and consequences not only for Vicente Morales and Rafael Monroy and their respective families but also for the whole San Marcos Church membership and subsequent converts. Beyond, these events articulated the long process of institutionalizing the Church in San Marcos.

This book scans the background and details of some of those causes and consequences not only for Church members but also for the Church as an institution in San Marcos. Specifically, it reflects on the lives of Rafael Monroy and Vicente Morales as martyrs in their faith and later studies the executions as a reflection not only of the Revolution of 1910–17 but also of the international political economy undergirding it. The monograph examines the conversions of the Monroy family and of Vicente Morales within the context of Mexico’s contesting political ideologies and thereafter looks into the aftermath of the martyrdoms for the members in San Marcos. It shows how numerous members eventually rose above their tribulations and substantial personal failings to bequeath to the present-day LDS Church an example of profound personal and institutional fidelity. Finally, it examines how the Church became institutionalized in San Marcos, Tula, Hidalgo.

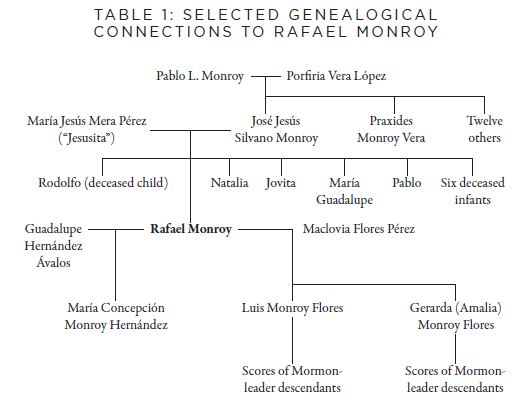

Rafael Monroy Mera (1878–1915)

Before moving to San Marcos in December of 1906, Rafael’s immediate family had become relatively well off elsewhere in Hidalgo. Various members worked as hacienda administrators, teachers, and governmental employees. For generations, the Monroy family had striven to be upwardly mobile, to rise from servitude to independence and beyond, and there is evidence of success. For example, Rafael’s grandfather Pablo L. Monroy along with Pablo’s wife, Porfiria Vera López, sat in elegant dress around 1875 for a photograph[6] just a decade following the popularizing of the new technology in Mexico during the years of the French intervention (1864–67). (The Austrian emperor Maximilian, who Napoleon III had installed over Mexico, was a boundless fan of photos and circulated many of Empress Carlotta and him to try to legitimize his French-imposed reign.)[7] Moreover, Rafael’s grandfather had been able to educate at least some of his fourteen children. His son José Jesús Silvano Monroy Vera, who became Rafael Monroy’s father, certainly was literate, as was his sister, Praxedis Monroy Vera, who was, in fact, a schoolteacher in El Arenal, Hidalgo (located forty-five miles northeast of San Marcos). Later, she helped her nieces Natalia and Jovita, Rafael’s sisters, to become state-appointed teachers in small villages or hamlets relatively close to the Monroy extended family. As customary for the times, the teenage teachers’ students ranged in age from very young (ca. age six) to advanced (ca. age fifteen and sometimes older), all highly desirous to begin their first year of formal education.[8]

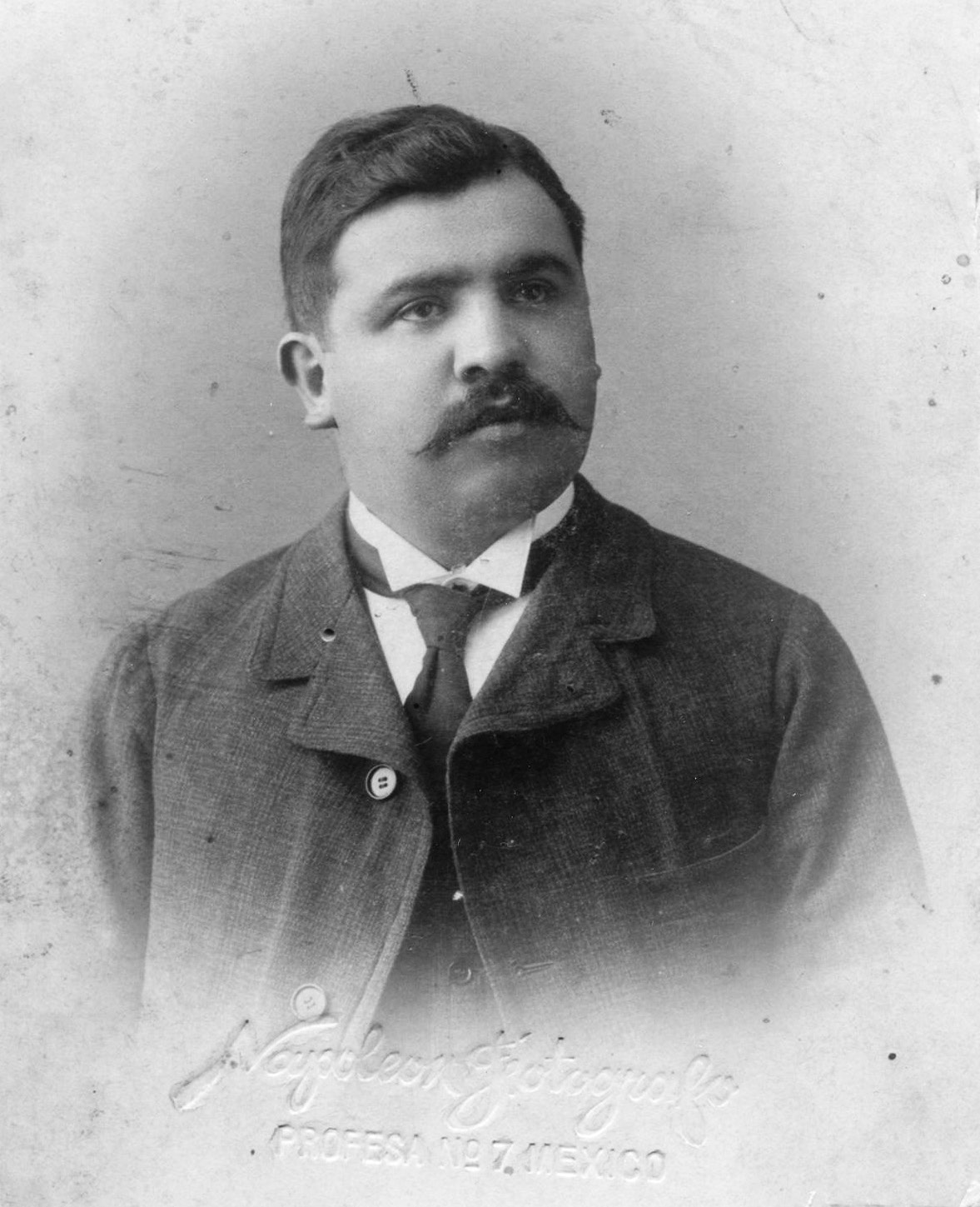

Portrait of Rafael Monroy done by the studio Napoleón Fotografía in Mexico City, ca. 1911. The venue, attire, and quality of the portrait suggest that the Monroy family was relatively well off economically. This image was cropped and enhanced from the original. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Portrait of Rafael Monroy done by the studio Napoleón Fotografía in Mexico City, ca. 1911. The venue, attire, and quality of the portrait suggest that the Monroy family was relatively well off economically. This image was cropped and enhanced from the original. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Rafael’s father was already an administrator of haciendas (administrador de haciendas) when he and the much younger María Jesús Mera Pérez (she went by Jesusita to distinguish her name from that of her partner, José Silvano de Jesús) decided to live together, a decision they later solemnized with a formal marriage.[9] Jesusita came from impoverished parents who worked on various ranchos in the vicinity. She was unable to attend any school until age thirteen, when she began to remediate her illiteracy. She was keen to study whenever she had a chance, and through the years she became respectably self-taught, although she always claimed not to know how to read or write well.[10]

María Jesús Mera Pérez de Monroy, known as Jesusita, mother of Rafael Monroy Mera, ca. 1911. Courtesy of Church History Library.

María Jesús Mera Pérez de Monroy, known as Jesusita, mother of Rafael Monroy Mera, ca. 1911. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Thinking about what would be best for the children that Jesusita and her partner expected would bless their home,[11] the couple eventually decided to move to where at least rudimentary educational opportunities existed. Rafael’s father resigned his administrative position, and the couple moved to El Arenal, six miles northwest of Actopan, to be near his extended family and the educational resources they nurtured. Rafael’s parents-to-be were intent that their yet unborn offspring should have an opportunity to be formally educated in order to rise above the toil of ordinary country life.[12]

With opportunities at hand, members of the Monroy extended family in El Arenal, especially José Silvano de Jesús’s sister Praxedis Monroy, taught all the children in El Arenal who were willing to work to become literate, and she and other members of the extended family gave extensive educational help to the children in the extended Monroy family. Accordingly, Rafael and his surviving younger siblings (Natalia, Jovita, Guadalupe, and Pablo) learned to read and write. Tellingly, their parents valued education enough not only to make opportunities available but also to free the children from domestic and field chores sufficiently to allow them to pursue it, which was, in the short term, an economic sacrifice for the parents.

Aside from becoming literate, Rafael grew up learning administrative skills from his father and grandfather, experiences that landed him a full administrative title in 1903 at age twenty-four, when his father, then the administrator of the Hacienda del Cedó near Actopan, suddenly died at age fifty. The hacienda owners debated about whom to appoint as the administrative successor. They settled on Rafael.

Conforming to the common practice of the times and certainly following a pattern that his father had set,[13] Rafael began about this time a nearly three-year romantic relationship with Maclovia Flores Pérez that produced two children, Luis and Gerarda (the latter was known as Amalia Monroy after age twelve).[14] Gerarda (Amalia) was born on 3 October 1906 in Llano Largo, Hidalgo, near the Hacienda del Cedó, where her mother, Maclovia, also was employed.

In late October 1906, shortly after the birth of Gerarda, Rafael resigned as administrator of the Hacienda del Cedó; split with his children’s mother, Maclovia; and—along with his mother, Jesusita, and siblings—moved to Tecajique, Hidalgo, for a couple of months. In December 1906, the Monroy family moved to San Marcos. Maclovia remained at work at the Hacienda del Cedó, and her children, Luis and Gerarda, stayed with her.

Gerarda stayed with her mother for twelve years. A year after her mother’s death in 1918, Gerarda eventually moved to the custody of her father in San Marcos and was renamed Amalia.[15]

Monroy family with missionaries and friends on an excursion, ca. 1922. Amalia Monroy, daughter of Rafael Monroy and Maclovia Flores Pérez, is standing at the left, ca. 1922. Around 1918 she came to live in the Monroy compound in San Marcos, Hidalgo. Courtesy of Maclovia Monroy de Montoya.

Monroy family with missionaries and friends on an excursion, ca. 1922. Amalia Monroy, daughter of Rafael Monroy and Maclovia Flores Pérez, is standing at the left, ca. 1922. Around 1918 she came to live in the Monroy compound in San Marcos, Hidalgo. Courtesy of Maclovia Monroy de Montoya.

In addition to learning how to be an hacienda administrator from his father, Rafael also learned at least one additional skill from him: the need—if not the art—of cultivating good relations with governmental officials. Indeed, assiduously nurturing relations with Hidalgo’s politicians and administrators had been front and center during the family’s entire time at the Hacienda del Cedó (1898–1906). Rafael acquired political visibility in the municipality (county) of Tula (in the state of Hidalgo), where authorities gave him various tasks relating to the development of agriculture and irrigation in the region. Any number of locals sought his advice regarding their business and ranching dealings.[16]

Rafael and his brother Pablo, who would soon die in San Marcos at age nineteen,[17] shortly took employment in the valley of Tula—Rafael as a police commander in Tula and Pablo as manager of Tula’s municipal slaughterhouse. Their sisters Natalia and Jovita kept their teaching positions but later—along with their sister Guadalupe and mother, Jesusita—joined Rafael in San Marcos, where he had been able to acquire the lands knows as El Godo and El Capulín. Rafael helped Natalia and his mother, Jesusita, establish a store (tienda) in San Marcos, which seemed to be every woman’s favorite wish.[18] Starting out in rented quarters near San Marcos’s central plaza, the family eventually built a home at El Capulín. It was in that house, in what became a casa de oración, a house of worship, that the first twentieth-century meetings of the LDS Church in that area took place.[19]

While living in San Marcos, Rafael Monroy developed a romantic relationship with Guadalupe Hernández Ávalos, whom he apparently had known for some time through his extended family. Guadalupe Hernández lived in San Agustín Tlaxiaca, Hidalgo (forty-five miles northeast of San Marcos), and there, in 1909 or 1910, she and Rafael Monroy were married.[20] In due course, they produced a daughter, María Concepción.

Wedding of Rafael Monroy Mera and Guadalupe Hernández Ávalos, San Agustín Tlaxiaca, Hidalgo, Mexico, 6 January 1909. Courtesy of Maclovia Monroy de Montoya.

Wedding of Rafael Monroy Mera and Guadalupe Hernández Ávalos, San Agustín Tlaxiaca, Hidalgo, Mexico, 6 January 1909. Courtesy of Maclovia Monroy de Montoya.

When Rafael and Guadalupe’s daughter was two years old, Rafael began to develop an interest in the LDS missionary discussions. He took particular interest not only in the Book of Mormon as a compelling document but also in the Restoration’s teachings about God’s relationship with his earthly children and his requirement that they repent of their sins and be baptized.

Except for Rafael’s wife, who was not happy about all this and had done her best to thwart the missionaries’ efforts,[21] the whole Monroy family was mesmerized at Joseph Smith’s hand in the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ and, in particular, his work in translating the Book of Mormon. Accordingly, and not surprisingly, Rafael and his sisters Guadalupe and Jovita were baptized in 1913, and soon their mother, Jesusita, joined them. Surprisingly, and despite her early foot dragging, Rafael’s wife, Guadalupe, was also baptized a month and a half later.[22] W. Ernest Young had discharged his missionary duties well.[23]

The family’s relatively good social and economic status in the community notwithstanding, Rafael, his sisters, and their mother soon felt the scimitar of persecution for having abandoned, in the eyes of their neighbors, the teachings of the community’s ancestors to join an alien US church.[24] Associating with foreigners was particularly anathema to the xenophobic Zapatistas from the state of Morelos, whose armed militia would later occupy the village.

Persecution aside, the Monroy home became the Church’s meeting place for what would become a gradually increasing number of Mormons in San Marcos. Vicente Morales moved in from Puebla to help.

Vicente Morales Guerrero (1887–1915)

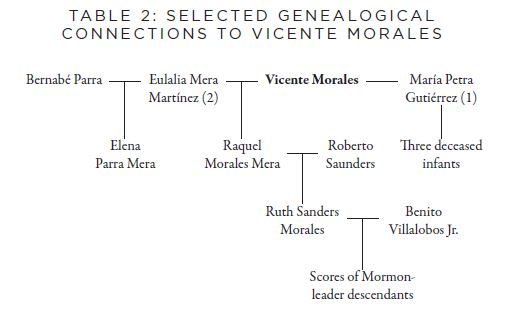

The rapidly assembled insurgent Zapatista firing squad that ended the life of Rafael Monroy Mera in 1915 also terminated that of his cousin-in-law, employee, and counselor in the San Marcos Branch presidency, twenty-nine-year-old Vicente Morales Guerrero.

If in the Zapatista mind a constellation of factors condemned Monroy to a firing squad (his religious persuasion being only one among several), the matter appeared to be less complicated for the Zapatista general regarding Morales. Morales was a Mormon, was therefore pairing with aliens, and was a confidant of the aspiring middle-class Monroy, who would not confess his alleged crimes, no matter the torture. Even worse, Morales would not betray Monroy by doing the confessing himself. That was enough. In those days, examination of evidence was not a hallmark of the Zapatistas’ minds except insofar as it affected their own sense of oppression and maltreatment at the hands of Mexico’s privileged classes. Spiteful vengeance (venganza rencorosa), not to mention indiscriminate vengeance, is a powerful motivator of malevolence. In the Mexican Revolution (1910–17), spiteful and indiscriminate vengeance amply fueled grief and despair as pandemonium enveloped the land like smoke from a million wildfires.

Vicente Morales was born among the indigenous Otomí in the municipality of Alfajayucan, in the state of Hidalgo.[25] He was living in Cuautla, in the state of Morelos, when he became acquainted with the Church, which he joined in 1907 at age twenty. From age seventeen, he had been in a common-law relationship with María Petra Gutiérrez, four years his junior, with whom he had begotten and buried two daughters by 1907. After Vicente and María legalized their union through marriage to facilitate Vicente’s baptism (which must have comforted María, given that she had joined the Church in Toluca at age ten), the couple had one more daughter (1909), who, like the others, died before her first birthday. In less than two years thereafter, María herself died (1911) from unrecorded causes, but perhaps related to another pregnancy.

With the family of his first love wiped out, and savaged by unremitting grief and despair, Morales nevertheless cemented himself in the Church by accepting a call as a part-time local missionary when regular missionaries fled Mexico in August of 1913 due to war hostilities.[26] Given his difficulty in speaking the Spanish language (his native tongue being Otomí), his acceptance of a mission assignment to Spanish speakers was of itself quite remarkable.[27] His missionary efforts eventually took him to San Marcos, Hidalgo, where he made several visits. Specifically, from January to March 1914, he and his traveling companions met with the Monroy family on at least three separate occasions to give them postbaptism gospel teachings.

The civil war was displacing hundreds of thousands of people, among them many Mormons, including Casimiro Gutiérrez and Plácida González, the parents of Vicente’s deceased wife, María. Toluca, where they had been residing, was either aflame or in rubble, and Casimiro and Plácida, along with their other children, fled to San Marcos and to the community of Mormons there, hoping for safety. After the martyrdoms, Casimiro assumed the office of branch president,[28] but that he and his family were in San Marcos beforehand probably encouraged Vicente to make numerous visits to his parents-in-law as the widower dealt with his grief.[29]

Ultimately, however, there was perhaps a more compelling reason for Vicente to be attracted to San Marcos as a local missionary. Her name was Eulalia Mera Martínez, the seventeen-year-old niece of Rafael Monroy’s mother, Jesusita, and therefore Rafael’s cousin, who was living in the Monroy compound. Her appearance, typical of a youthful Otomí as revealed in the one extant photo we have seen, was very appealing to Vicente. Indeed, Eulalia was beautiful, had come of age, and was a member of the Church. Although Vicente had lost three children and his wife, and although he was more than a decade older than Eulalia, he nevertheless wondered if the young woman might be interested in him. He was stable, had none of the regular male vices of the day, was a strong member of the Church who was faithful to its teachings, and was considered by some to be quite handsome. They were both of Otomí heritage. So, he wondered.

Around 1912, then-fifteen-year-old Eulalia had moved to San Marcos from the municipal seat of Tula, Hidalgo. Jesusita took her niece in as if she were one of her own, a deed Jesusita had done before and would continue to do for others on numerous occasions. Eulalia was not long in her new home before she accepted the Mormon faith and was baptized (1913). By mid-1914, she had taken a liking to Morales, and, within a year, that liking matured. With President Rey L. Pratt’s written permission (necessary because Vicente had a missionary calling) delivered from the United States, where he had taken refuge from the civil war, Vicente and seventeen-year-old Eulalia were married in San Marcos in early January 1915, just six and a half months before Morales’s execution.[30] In March, when the fratricide of the civil war subsided for a few weeks, they had their marriage registered with civil authority in Tula—at least that part of civil authority that still functioned in Hidalgo.

The wedding celebration held in the Monroy compound was a grand affair. More than fifty people joined the gala. In addition to his extended family from the Rodríguez and Casimiro Gutiérrez clans, Vicente had invited many of his friends and acquaintances from other Church branches where he had served as a local missionary. Even Agustín Haro, the president of the San Pedro Mártir Branch, then in great distress as its members were scattering due to the war, showed up for the celebration.

Afterward, the invitees met in the one activity that always united them whether in celebration or in distress—a testimony meeting. A wedding celebration punctuated by a testimony meeting may seem strange. For the San Marcos members, such meetings were always the highlight of the first Sunday of the month as well as for every other occasion they could conjure up, including funerals and picnics in the countryside.[31] And, this time, it was a wedding.

When the Zapatista bullets pierced Vicente’s body on 17 July 1915, his daughter Raquel was still in utero. Eulalia was five months pregnant when she heard the Zapatista fusillade that killed her husband and her cousin Rafael Monroy. Let us look at the background to these events.

Notes

[1] The Spanish rendition as recorded by Rafael’s sister Guadalupe is “¡Qué valor de hombre! ¡Han muerto con sus calzones en su lugar!” María Guadalupe Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio Restaurado al Pueblo de San Marcos, Tula de Allende, Estado de Hidalgo,” Linaje Monroy en el Estado de Hidalgo, México, 1944, 27, https://

[2] An excellent analysis of the events leading up to the executions is Mark L. Grover, “Execution in Mexico: The Deaths of Rafael Monroy and Vicente Morales,” BYU Studies 35, no. 3 (1995–96): 7–28. See also LaMond Tullis, Mormons in Mexico: The Dynamics of Faith and Culture (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987), 100–103, 109–10.

[3] Winchester M1895 lever-action and Springfield M1903 bolt-action rifles were those generally used by Emiliano Zapata’s loosely structured revolutionary bands, the Zapatistas, and Francisco (Pancho) Villa’s revolutionary forces, the Villistas. During Mexico’s civil war of 1910–17, the Villistas, along with other revolutionary groups, sought to topple the country’s federal government and rupture the dysfunctional and feudal society it coercively sustained. At the time of the San Marcos martyrdoms, the Zapatistas and the Villistas were in one of their sometimes-temporary alliances, at least in the state of Hidalgo. The Zapatistas, whose forces occupied San Marcos, appear to have been taking instructions, if not orders, from Villista commanders whose forces had occupied nearby Tula. As for the rifles and who used them, see “Weapons Used in the Mexican Revolution,” History Wars Weapons, www.historywarsweapons.com/

[4] Grover, “Execution in Mexico”; Tullis, Mormons in Mexico, 100–103, 109–10. Primary sources include Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 25–30; Jesús M. Vda. de Monroy to mission president Rey L. Pratt, 27 August 1915; Rey L. Pratt to Jesús M. Vda. de Monroy, 28 October 1915, from Manassa, Colorado, where he had taken refuge from the Mexican Revolution; and Diary of W. Ernest Young, Appendix I, 669–85. Secondary sources include Rey L. Pratt, “A Latter-day Martyr,” Improvement Era 21 (June 1918): 720–26; Rey L. Pratt, in Conference Report, April 1920, 87–93; “Two Members Died Courageously for the Truth,” Church News, 12 September 1959; Jack E. Jarrard, “Martyrdom in Mexico,” Church News, 3 July 1971; and numerous entries elsewhere based mostly on those previously mentioned. As for films, the visitors’ center in Mexico City has a short clip on the assassinations. The most widely known is the somewhat ahistorical video And Should We Die (1966), written by Scott Whitaker and produced by Brigham Young University.

[5] Kirk Henrichsen has been planning a video. From the preliminary screenplay outline, the outcome will likely be the best film yet on the martyrdoms and their context. Kirk Henrichsen, “Preliminary Screenplay Outline Notes,” 19 March 2014. Copy provided by Hugo Montoya Monroy.

[6] The photograph appears in “Historia de Rafael Monroy,” Linaje Monroy en el Estado de Hidalgo, México, 1, https://

[7] For a treatise on early photography in Mexico, see Beth Ann Guynn, “A Nation Emerges: 65 Years of Photography in Mexico,” Getty Research Institute, http://

[8] Minerva Montoya Monroy to LaMond Tullis, email, 21 September 2016, citing the diary of María Guadalupe Monroy Mera, 31.

[9] Following the birth of the fifth of their thirteen children (five of whom survived infancy), the couple was married on 3 June 1886. Common-law unions were the norm at the time, as was profligate infidelity. For example, Rafael’s father had unions with at least four other women who bore him children. “Historia de Rafael Monroy.”

[10] “Biografía de Mamá Jesusita Mera Narrada por Minerva Montoya Monroy,” typescript, five pages, n.d. Copy provided by Hugo Montoya Monroy, 1 March 2014. Minerva gleaned her information from El Diario de María Guadalupe Monroy Mera, 6–7. Jesusita said that because of the family’s poor economic situation, she was unable to attend school. By this, she meant she could not attend until age thirteen and likely not for more than a year or so afterward. For that reason, she viewed herself as not being able to read well.

[11] Children, aside from being loved, were also a culturally valued demonstration of virility and fecundity and were generally considered an economic asset to a family because they could be put to work in the fields around age six.

[12] “Historia de Rafael Monroy,” 2.

[13] “Jesús Monroy had other sexual partners, e.g., Vicenta Ríos, Marciala, Valentina Bisuet y Petra Vera, with whom he had other children.” See “Historia de Rafael Monroy,” 3.

[14] A picture of Agustina Marcelina Maclovia Flores Pérez shows that she was a beautiful young woman. The children were Luis Monroy Flores (1904) and Gerarda Monroy Flores (1906). “Historia de Rafael Monroy,” 5.

[15] Hugo Montoya Monroy, comments to the author.

[16] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 3.

[17] María Concepción Monroy de Villalobos, oral history interview by Gordon Irving, 1974, typescript, James Moyle Oral History Program, Church History Library, 1–2.

[18] In her diary, Guadalupe says the store was established for Natalia. Minerva Montoya Monroy to LaMond Tullis, email, 21 September 2016, citing pp. 43 and 48 from the diary.

[19] Members from an earlier 1880–81 period are noted (e.g., Jesús Sánchez), although we have not seen any record that indicates they held meetings in San Marcos. “Historia de Rafael Monroy,” 14.

[20] When Rafael Monroy and Guadalupe Hernández joined in marriage on 8 January 1909 (Hugo Montoya Monroy’s date) or 6 Janaury 1910 (María Guadalupe Monroy Mera’s date from her diary), Maclovia appeared to give up on any thought of reconciliation with Rafael. She subsequently began a relationship with Santos Ortiz that produced two girls, Juliana and Alfonsa. We do not know if Rafael maintained any communication with Maclovia and his children. However, several fragments in the history of the family indicate that from time to time, Rafael mentioned his children with Maclovia. Hugo Montoya Monroy to LaMond Tullis, 27 February 2014.

[21] Grover, “Execution in Mexico,” 11.

[22] Walter Ernest Young, The Diary of W. Ernest Young (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1973), 107.

[23] On 11 June 1913, W. Ernest Young performed the baptisms, while mission president Rey L. Pratt witnessed the baptisms. Young, Diary, 658–60. See also the narrative of Guadalupe Monroy Mera, one of those baptized, in “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 4–5.

[24] Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 3–45.

[25] Ruth Josefina Saunders Morales de Villalobos (daughter of Raquel Morales Mera and granddaughter of Vicente Morales) to LaMond Tullis, 11 February 2014. Morales’s case illustrates the problem of gathering genealogical information in Mexico. Although one source alleges that Morales was born in Cuautla, there are no extant records. All the recorded vital statistics in Morelos prior to about 1912 were burned during the civil war. Guadalupe Monroy, who knew Morales perhaps as well as anyone except his immediate relatives (who left no records), affirms that he was born in Hidalgo, as stated in the text. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 7.

As for the Otomíes, they predated the Aztecs, who arrived in the central Mexican plateau around AD 1000. The Otomíes existed in numerous subethnic groups, speaking several and sometimes mutually intelligible variants of the Otomí language. Many of their ancestral customs and language variants prevail into 2018. Their ancient homeland included portions of the present state of Hidalgo, but descendants are now located in major numbers in the states of Hidalgo and Querétaro. Other identifiable and smaller Otomí populations exist in the states of Puebla, México, Tlaxcala, Michoacán, and Guanajuato. For a perceptive discussion of the Otomíes in one area, see Mateo Cajero, Historia de los Otomíes en Ixtenco, 2nd ed. (Bristol: University of the West of England, Bristol, 2009).

[26] The call probably came from Agustín Haro, president of the San Pedro Mártir Branch, which, along with the Ixtacalco Branch, undertook supervision of San Marcos when the full-time missionaries and President Rey L. Pratt fled Mexico. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 7–48. Haro, whose own work in the Church has become legendary, was Casimiro González’s brother-in-law. Saunders Morales to Tullis.

[27] Saunders Morales to Tullis. Additionally, accomplished writer Guadalupe Monroy put it this way: Morales “was quite poor and spoke Spanish incorrectly or with a bad pronunciation because his mother tongue was Otomí. He was from Alfayayucan from the state of Hidalgo. Luck had extracted him from there and he had accepted the gospel.” (Morales “era un hermano de humilde condición, hablaba el idioma Español muy incorrectamente o mal pronunciado porque su idioma natal era el otomí. Él era del Pueblo de Alfajayucan del estado de Hidalgo y la suerte lo había sacado de aquellos lugares y había aceptado el Evangelio.) Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 7.

[28] Saunders Morales to Tullis. See also Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 110–11.

[29] The record does not disclose when Morales first began his missionary work in San Marcos, but he was there with his companion Juan García on 25 January 1914, when they met with the Monroys. On this occasion, Vicente was known as having the office of deacon and his companion as being a teacher. A month later, he returned with his companion Ángel López and yet a month later with Antonio Pérez. By this time, Vicente held the office of teacher. Others who accompanied him to San Marcos and visited the Monroys were Anacleto Rodríguez and Francisco Rodríguez. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 7–9.

[30] Vicente Morales and Eulalia Mera were married 4 January 1915. Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 13. Further corroboration in Familia Montoya Monroy, “Martirio en México,” Linaje Monroy en el Estado de Hidalgo, México, 17 January 2014, 3, https://

[31] Guadalupe Monroy’s extraordinary detail in her records over twenty years includes not only the names of those who bore their testimonies in these meetings but also summaries of what they said. In this case, see Monroy Mera, “Como Llegó el Evangelio,” 13.