Hinduism

Roger R. Keller, "Hinduism," Light and Truth: A Latter-day Saint Guide to World Religions (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 16–39.

Hinduism is a highly varied faith, but it is beautiful in its diversity. People seek God, and for those who live their faith well, they live very much as do Latter-day Saints with similar standards and values.

Temple in Belur, India. Central to Hindu worship is seeing the god housed within his or her temple. All images courtesy of author unless otherwise noted.

Temple in Belur, India. Central to Hindu worship is seeing the god housed within his or her temple. All images courtesy of author unless otherwise noted.

Hinduism is a vibrant, multifaceted faith with roots deep in India’s soil. Most of its nine hundred million adherents [1] are in India, but many Hindus have left India for educational or vocational reasons, creating thriving communities all over the world. The Hindu umbrella is large, incorporating polytheists, monotheists, and atheists. It is generally a nonmissionary faith, with the belief that all persons follow the way they made for themselves in prior lives and that the way they follow is uniquely theirs. Not only is it hard for Hindus to understand the missionary zeal of Christianity and Islam, but they also resent the implication that their indigenous religion is inferior or inadequate when compared with other faiths. Hinduism has many sensible answers to human questions and meets many human needs, so this chapter will attempt to show Hinduism in its beauty and diversity while in conversation with Latter-day Saint thought.

Origins

A Hindu Position

Hinduism holds itself to be one of the oldest faiths, if not the oldest faith, on the face of the earth. From a Hindu perspective, the precepts that make up Hinduism can be traced back to ancient wise men living far back in the mists of time who heard the vibrations of the universe, received them, and passed them along orally to others who continued the transmission. These oral traditions were passed along among a people known as the Aryans, whose origins are not clear. Eventually their oral traditions were written down, and today these make up the most sacred portion of the Hindu scriptures. They are texts that are believed to have no human authors but rather emanated from either the depths of the universe or the all-encompassing deity, dependent upon one’s Hindu perspective. [2]

A Historical View of the Religion

From the standpoint of the history of religions, Hinduism is viewed by scholars as an amalgamation of the Aryan religion and the religion of a people known as the Dravidians from the Indus Valley Culture. The Dravidians were the original inhabitants of the Indus Valley, which lies in current-day Pakistan. We know very little about them, since the written script they used is found in few places and has therefore not been translated. Thus our knowledge of the Dravidians is based on archaeology. Archaeology suggests that they were agriculturalists and that they had a highly developed civilization as evidenced by the population centers of Harappa and Mohenjo Daro. Both centers had public water and sewage systems, public baths, and other refinements. Small figurines of bulls and nude women suggest that the religion of the Dravidians was a fertility cult. In addition, we know that they were a black-skinned people but not Negroid, based on their descendants, known as Tamils, who still live in India, especially in the south.

By contrast, the Aryans were a Caucasian nomadic, herding people, perhaps coming from the steppes of Russia, although scholarly opinion is not at one on this issue. Around 1500 BCE, they began to migrate in search of pasture for their flocks and herds. Some moved into the Indus Valley; others traveled into Persia, the Greek Peloponnesus, Europe, and Scandinavia. In other words, the Aryans are the ancestors of those whose roots lie in Europe. Among scholars, there seems to be a growing consensus that there was a gradual Aryan migration, with the Dravidians already beginning to move out by the time the Aryans arrived due to a changing climate that was making it harder to raise crops. The land was becoming more suited to a pastoral life than to an agrarian one. Be that as it may, a great deal is known about the Aryans because we have their writings, these being known as the Vedas. We learn from the Vedas that the Aryans worshiped nature gods, had an elaborate sacrificial system, and had a priestly structure to carry out their sacrifices. The scholarly argument contends that Hinduism arose from the interaction of these two cultures, which lived side by side for a millennium.

Bull Nandi, Birla temple. Small figurines of bulls suggest that the religion of the Dravidians was a fertility cult.

Bull Nandi, Birla temple. Small figurines of bulls suggest that the religion of the Dravidians was a fertility cult.

Scripture

Shruti. The Hindu scriptures are divided into two categories: the Shruti and the Smriti. Shruti means “that which is heard,” and these contain those texts which were heard by the ancient wise men eons ago. The wise men were not the authors of these texts, but rather, they received them more in the manner of a court reporter who writes down what has been said. These texts are in Sanskrit and are the province of scholars and priests; most are used in support of sacrificial rituals.

The foundational Hindu texts, the Vedas, include the Rig Veda (“Wisdom Consisting of Verses”), which is recited by “caller priests” who invite the gods to the sacrifices; the Sama Veda ("Knowledge of Melodies”), which is sung by “singer priests” in support of the sacrificial rituals; the Yajur Veda (“Knowledge of Sacrificial Sayings”), which is chanted by the “sacrificial priests” during the sacrifices; and finally the Atharva Veda (“Knowledge of Magic Sayings”), which is primarily concerned with diverting disasters.

In addition to the Vedas, the Shruti contain philosophical commentaries on the sacrificial process; internal meditative rituals to be performed in the forest; [3] and philosophical treatises which begin to deal with reincarnation, the identity between the world soul and the human soul, and the ascetic life of the forest monk.

Smriti. The Smriti, meaning “that which is remembered,” have human authors who write what they know, often in story form, and incorporate in their stories the principles that are contained in the Shruti. However, the Smriti are much more “user friendly.” Many of them are attractive stories that keep the interest of the lay reader, and they are read and told in the average home. Thus, most Hindus are far more familiar with parts of the Smriti than they are with parts of the Shruti. The Smriti contain stories and legends about gods and their activities that are somewhat similar to Aesop’s Fables, which are told to educate as well as entertain. They also contain the Mahabharata, a huge epic poem which exceeds in length The Iliad and The Odyssey combined. The poem narrates the wars and interactions between two ancient Indian families—the Pandavas and the Kauravas—and very probably has its roots deep in the soil of ancient India. One chapter within the Mahabharata is the Bhagavad Gita, the most sacred book of the Hare Krishna sect of Hinduism. The power in the Bhagavad Gita is Krishna’s teaching about the role of devotion to him in salvation and is loved by all Hindus. The Ramayana is a wonderful story of the love between the god Rama and his wife, Sita, and the battle between good and evil. Because of these themes, the Ramayana is a popular story among all Hindus, but it also cuts across cultural lines. The author has seen it performed in the Sultan’s palace in Yogjakarta, Indonesia, a country that is 95 percent Muslim. He has also seen it performed in Bangkok, Thailand, a country that is virtually all Buddhist, and of course it has been performed in India and the United States. In all cases, it is thoroughly enjoyed. Finally, the Laws of Manu address the laws that guide the various castes, as well as the proper roles for women and the various rites of passage in Hindu life. It is clearly written from the male, priestly perspective.

The Hindu Worldview

Aryan Deities

Some of the gods that were part of the Aryan religion still play a significant role in present-day Hinduism. For example, Indra is the king of the gods and a storm god. He is the ruler of the middle sky and the god of the monsoon storms, which bring life to India annually. He was very much the patron god of the Aryans, and those who attacked the Aryans attacked Indra, who would fight on behalf of his people.

Agni is the god of fire. Essentially, he is the messenger boy who carries the sacrifices from earth to heaven. Soma is the god of immortality, and by drinking soma, a hallucinogenic drink, one may take on the characteristics of the god. Thus, warriors often drank soma before entering into battle. It may seem strange that there is the close tie between something material (i.e., the drink soma) and the god Soma. However, if Latter-day Saints will think about what actually happens in taking the sacrament, they will realize that there is a close connection between the elements of bread and water, which worshipers take into themselves, and Jesus Christ, with whom the worshipers identify through the material elements of bread and water and the Spirit. Because of that identification, worshipers leave the sacrament table as clean and pure as they were the moment they emerged from the baptismal pool. They have taken upon themselves the name of Christ (or Christ himself) and have thereby received his perfection.

One final god derived from the Aryans is Brahmanaspati, who is the god who knows how to influence the other gods, or is the power in prayer which moves the gods. People who know how to control Brahmanaspati have tremendous power—the power that the Brahmins, the priests, are believed to hold. For this reason, the priests stand atop the social structure known as the caste system. While there may be many persons with power in the temporal realm that can kill and destroy, only the priests have the power to influence the gods. They have cosmic power through Brahmanaspati. A parallel to Brahmanaspati in Latter-day Saint thought could be priesthood power. Through it, we can draw on the very power that God himself uses. However, rather than influencing God, as do the Brahmins, priesthood is used to bring God’s power and influence to earth and to people.

Caste and Social Responsibility

Probably one of the most recognized but least understood aspects of Indian life is the caste system, or the system of social segregation. It is probable that the hierarchical social structure defined by priests did not exist among the Aryans, for nomadic societies tend to be divided on the basis of responsibility, creating a horizontal structure. However, when the Aryans finally settled in the Indus Valley, what previously was a vocational grouping became vertical and hereditary, and thus one’s caste was defined by the caste of one’s parents. Marriage and social relationships were and still are to be within castes, thereby stratifying the society. A text that defined traditional caste responsibilities comes from the Institutes of Vishnu 2—1.17 and reads:

Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras are the four castes. The first three of these are called twice-born. They must perform with mantras the whole number of ceremonies, which begin with impregnation and end with the ceremony of burning the dead body. Their duties are as follows. A Brahmin teaches the Veda. A Kshatriya has constant practice in arms. A Vaishya tends cattle. A Shudra serves the twice-born. All the twice-born are to sacrifice and study the Veda. [4]

From the above, it is clear that Brahmins perform the priestly tasks and are at the top of the system, because they know how to influence events at the cosmic level. A Brahmin presides at the sacrifices and performs them on behalf of others. In return, they give him alms which support him and his family. Kshatriyas were the warriors and the nobles who had tremendous temporal power and could make life good or bad for people, but they did not have the special knowledge of the Brahmins. Their basic job was to protect the community. Vaishyas were the people who really made society work. They were the farmers, merchants, accountants, money lenders, etc. Finally, the Shudras were the servant class and were involved in various trades or crafts.

Twice-born. We should notice the reference to the “twice-born” in the passage above. The male members of the first three castes may be twice-born, meaning that they could be initiated into the full range of responsibilities within Hindu society, particularly that of studying the sacred texts and performing the prescribed ceremonies of religious life. At various canonical ages, the three twice-born castes can receive a sacred thread which is worn over the left shoulder for life. The ceremony marks the entrance of the young man into adulthood. There are certain appropriate times for the ceremony, depending on caste, as well as certain things which are received, again depending on caste. Twice-born they may be, but equal they are not.

The fourth caste, the Shudras, are not twice-born because they are not believed to have sufficient spirituality to perform the rituals and sacrifices, much less study the sacred texts. Given this, however, all castes have certain common responsibilities according to the Institutes of Vishnu 2—1.17:

Duties common to all castes are patience, truthfulness, restraint, purity, liberality, self-control, not to kill, obedience toward one’s gurus, visiting places of pilgrimage, sympathy, straightforwardness, freedom from covetousness, reverence toward gods and Brahmins, and freedom from anger. [5]

Few religious persons could fault these values.

In addition to the classical four castes, there is also another group that is outside the caste system, but for all intents and purposes, it is a caste in itself. These people are known as the Untouchables or outcasts. These were probably people of Dravidian descent, while the four castes were probably of the Aryan race. The Untouchables were and are those who hold the lowest and most impure jobs in society, such as tanners and persons who work with sewage, clean the streets, or burn dead bodies. Because Gandhi did not believe that people should be categorized by parentage, he called the Untouchables Harijans, which means “children of God.” In other words, people are what they make themselves by their actions, not by their birth. There are Brahmins who behave as Untouchables, and there are Untouchables who behave as Brahmins. People should be accepted in society based on their behavior, in Gandhi’s view. Today, the Indian Constitution prohibits discrimination based on caste for jobs and political offices. There are even parliamentary seats reserved for members of the “scheduled castes” (Untouchables), so that all persons are represented. There are also groups within Hinduism that do not believe in the caste system, one of which is the Hare Krishnas.

The traditional four-caste system has been modified over time. Today, in each historical caste, as well as among the Harijans, there are many subcastes known as jatis. Usually, these are based on occupations, and it is around these that most Hindu life is oriented, for they function like the historic castes. One is born into them, has social relations within them, and marries within them. Thus, jatis are open or closed to one another, as were the historic castes, and India is still very conscious of caste or jati standing.

In closing the discussion of caste, it should be said that the caste system is not about economics but rather about spiritual standing. Shudras or Untouchables may be very rich, but they are spiritually light- years behind a dirt-poor Brahmin. The higher castes have some advantages educationally and financially, but neither of these is the ultimate goal of Hinduism. Rather, spirituality is the goal, and all else must ultimately be left behind to attain this. Consequently, the measure of a person is not his or her wealth but his or her spirituality. Thus, people are socially where they belong. Since they must live out the way they created for themselves, the caste and jati system creates a highly stable society.

This is quite different from the Latter-day Saint view, in which individuality and personal agency are stressed. Human beings control their own destinies. There is social mobility through hard work, education, and seizing opportunities. People are not locked into social positions by birth but may grow and advance through their best efforts. Among Latter-day Saints, class stratification is denied because God is not a respecter of persons. All are equal before him. All are his children, and he loves none more or less than others. However, he does give commands, and based on obedience to those commands, he rewards or condemns. Goodness, however, does not necessarily ensure material wealth or well-being.

Hence, caste in any form is anathema to Latter-day Saints. In the end, everything belongs to God, who gives all and who calls all to the service of their brothers and sisters. No church member is better than any other. All have been called to their own roles, but not because one is inherently better than another. We may show our differences in the way we respond to God, but for all of us, leadership is finally service, not status.

Hindu Philosophy

Monism

The traditional Brahmin worldview begins with a concept known as monism, the belief that all things are one. There is only one reality, and all things are simply extensions of that one which is called Brahman. Perhaps the best definition of Brahman is simply “Brahman is.” Thus, it is an illusion to believe that persons or other things have an identity separate and distinct from this world soul. As long as persons hold to the illusion of individual identity apart from Brahman, they will continue to return to the rounds of rebirth. Only when they come to an experiential knowledge of their oneness with Brahman will they finally be released.

The best example of the monistic worldview is that it would be an absolute illusion for a wave on the surface of the ocean to believe that it was something separate and distinct from the ocean. The human soul is the wave which appears momentarily and then vanishes. This would be pure monism.

However, most Hindus believe they have individuality and thus hold a modified monism. Their view would be more that of an ocean wave slamming into a cliff, and while the droplets of water, the souls, are in the air, they are truly separate from the ocean. But ultimately, they fall back into the ocean and all individuality is lost in the sea. In the end, all things are Brahman.

The concept of monism is foreign to the Latter-day Saint way of looking at the universe. The LDS perspective begins with the eternal nature of things. Matter, energy, intelligences, and God are all eternal and uncreated, but they are held to be distinct and separate. Matter, energy, and intelligences are not God, and thus he can organize them into universes, galaxies, star systems, animals, plants, fish, and fowl. The highest of God’s acts is the clothing of intelligences with spirit forms that bring men and women into the spirit world and ultimately, as with all life, to an earth. Thus, there is individuality to all things, though we share the thought with Hinduism that all is uncreated. Salvation is to find union with the Father through Christ, like Christ’s union with the Father, in which there is oneness in love, purpose, and will. In this union, however, humans do not lose their individuality in God; what they lose is their ego. We cannot take into God’s presence a will different from his. Satan tried that and was expelled. Neither are humans just an extension or piece of God. Instead they bear a divine spiritual nature derived from God. Consequently, the union Latter-day Saints experience is a spiritual union, not a material union.

Karma

How does monism fit with other concepts within Hinduism? Very well, for the system is quite tight. A principal concept is that of karma. Karma is what results from past actions, and it comes to fruition at various times and ways in various lives. In physics, every action has an equal and opposite reaction. So it is with karma, which explains many of the differences we observe in life. Why are some born wealthy and others poor? Because of karma. Why are some born perfect in body while others have birth defects? Because of karma. Why do some die early and others live to a ripe old age? Because of karma, and we did it all to ourselves. We are reaping what we have sown perhaps many lifetimes ago. We can have no objections to our situation in life because we created it for ourselves; and now we must live it out, although we can exercise our agency in how we live it. How we live it is defined by our caste laws and laws related to our sex or other stations in life.

Latter-day Saints have the idea of the law of the harvest, the point being that we reap what we sow. If we reject the offer of the Atonement, we are left responsible for our own acts. If we accept the Atonement, we will be blessed according to how faithfully we cling to Christ, how we live out the Christian life, and whether we accept the saving ordinances of the gospel offered through the priesthood. Thus, the Atonement can pay the price for our sins. The result of sin is not inexorable, as are the results of karma, thanks to Jesus Christ.

What about the relation between the premortal life, this life, and the consequences of our deeds in the former? By our very presence in this second estate, we know that we were faithful to the Father and to Jehovah when Satan led his revolt. Beyond that, we know very little about the exact correlation between the two estates, although we know that the great and valiant were reserved for the latter days. Often we assume these valiant persons to be only the Latter-day Saints, but there are many other persons of deep faith being born in these last times who improve the moral and spiritual content of human life, as we have already noted. They seem to have a role for which they too were foreordained. Given this, perhaps we as Latter-day Saints should concern ourselves more with the mercy and inclusiveness of God than with his justice and exclusivity. Perhaps, as President Hunter and Elder Orson F. Whitney suggested, God’s reach is much broader and more inclusive through his servants of many faiths than we might have supposed.

Reincarnation

Hindus believe in multiple lifetimes (i.e., the doctrine of reincarnation). It is clear to them that in one lifetime people cannot attain perfection sufficient for release from the rounds of rebirth, so there must be multiple lifetimes through which humans grow spiritually. While punishment for bad deeds certainly happens during the cycle of reincarnation, the underlying idea is one of growth toward spiritual things. Thus the Brahmins, the most spiritual of all groups, stand at the top of the caste system. Dependent upon their karma, persons may be reincarnated as any number of life-forms. The spectrum of life is as below.

Gods

Humans

Animals

Vegetation

Demons

Only as a human being may one find release from the wheel, for it is only as a human that one has agency or choice. Even the realm of the gods is only a place of rest and relaxation, but in the end, the gods must enter human life to find release. So it is with the lower life-forms. They are what they are because of karma, and they must remain as they are until the karma that placed them there is burned off. Karma is like a candle. When the candle finally burns down, all the fuel is exhausted. When the karma that placed one in a particular situation is burned up, new karma will come to fruition, and a new lifetime or life-form will occur with new opportunities for growth, if one is reincarnated in the human realm.

Latter-day Saints generally dismiss without much thought the doctrine of reincarnation. That, however, is too easy a response to the issue. The real question is, what is the problem with which the doctrine deals? The answer is that it deals with the reality that no one is able to be perfect in one lifetime. We all recognize that fact, no matter what our faith is.

Latter-day Saints also recognize the problem, although they give a different answer to it than does Hinduism. The Latter-day Saint answer lies in two principal doctrines: (1) the Atonement worked by Jesus Christ and (2) the doctrine of eternal progression. In the first instance, we do not have to become perfect, for Christ through his Atonement offers us his perfection. Each time we take the sacrament, we are made momentarily perfect in Christ. Ultimately, our goal is to live so near the Holy Ghost that we can be like Nephi in the book of Helaman, who was granted the right to ask for whatever he wanted, since he would never ask amiss. Most of us never attain that level of spirituality, but even Nephi leaned on Christ’s Atonement.

The second doctrine, that of eternal progression, simply means that we began our spiritual growth in the premortal life, continue that growth exponentially in mortality, and will continue to grow in our knowledge of God in the postmortal existence. Therefore, we may grow toward perfection in ourselves, a process that other Christians call sanctification. In this manner, Latter-day Saints deal with the issue of their imperfection. We must recognize that both approaches, the Hindu and the Latter-day Saint, make sense, given their underlying views of the world and of God.

Transmigration and Release

Coupled with reincarnation is the concept of transmigration, which many authors equate with reincarnation. However, as we will see with Buddhism, they are not equivalent. Transmigration means that something—my soul—moves from one life to another, and thus I am reborn. The soul is my essence until it falls back into the ocean, and until then, it moves from life to life.

In the end, however, the goal is to get out of these rounds of rebirth through release. To gain release, persons must break the illusion of their separateness from Brahman and come to a knowledge of their oneness with Brahman. But this is not “head knowledge.” The head only gets us into trouble, for our thoughts are not reality. Only Brahman is real. Historically, according to the Brahmin priests, when persons have lived lives of such merit that their karma is reduced to the degree that they have the propensity for release, they can enter the Brahmin path of study and meditation which ultimately leads to the enlightenment experience. This is a profound experience of oneness with all things or oneness with Brahman. It is not an intellectual knowledge but rather an experiential knowledge. When persons become enlightened and experience their oneness with Brahman, it is equivalent in Latter-day Saint terms to having our “calling and election made sure.” Persons know at death that they will be released from the rounds of rebirth. But release means what? It is the drop of water falling back into the ocean. This is nirvana, the loss of individuality and selfhood.

Nirvana

But why would one want to reach a state of nonexistence? To answer this, we must walk in the shoes of persons who live in a different world than do we, which is not the comfortable world of the West. In the United States, only a relatively few people have wanted for the essentials of life. Most have far more in goods and privileges than they can ever use. However, most of the world does not live this way, nor have our brothers and sisters across the millennia had such luxury. Most have lived on the edge of death. They were lucky to have any kind of meal every couple of days; they watched their children die; they were subject to the brutality of the more privileged; they were enslaved. If persons believed that lifetime after lifetime they would return to such situations, release might look good.

Latter-day Saints too experience the vicissitudes of life. Rather than seeing them as something to be escaped, they are viewed as growth opportunities. If we are not challenged, we cannot grow. With that said, we must still stand silent before some of the incredible suffering that people have to endure in our world. Much of it is due to the inhumanity of people to people, the hoarding of resources, and the desire for power. Some would suggest that it is due to choices we made in the premortal life, but I find that hard to accept. In considering the relationship between premortality and mortal life, Elder B. H. Roberts probably set the right tone:

Between these two extremes of good and bad, obedient and rebellious [in the premortal life] were, I doubt not, all degrees of faithfulness and nobility of conduct; and I hazard the opinion that the amount and kind of development in that pre-existent state influences the character in this life, and brings within reach of men privileges and blessings commensurate with their faithfulness in the spirit world. Yet I would not be understood as holding the opinion that those born to wealth and ease, whose lives appear to be an unbroken round of pleasure and happiness, must therefore have been spirits in their first estate that were very highly developed in refinement, and very valiant for God and his Christ. . . . I hold that the condition in life which is calculated to give the widest experience to man, is the one most to be desired, and he who obtains it is the most favored of God. . . . I believe it consistent with right reason to say that some of the lowliest walks in life, the paths which lead into the deepest valleys of sorrow and up to the most rugged steeps of adversity, are the ones which if a man travel in, will best accomplish the object of his existence in this world. . . . [T]hose who have to contend with difficulties, brave dangers, endure disappointments, struggle with sorrows, eat the bread of adversity and drink the water of affliction, develop a moral and spiritual strength, together with a purity of life and character, unknown to the heirs of ease, and wealth and pleasure. . . . In proof of this I direct you to the lives of the saints and the prophets; but above all to the life of the Son of God himself. [6]

Recognizing that the above is only Roberts’s opinion, the views certainly fit with all that we know from the restored gospel. It seems that life is not meant to be easy. It is designed to stretch and mold us, and it is definitely not to be escaped. We can be sure that evil is derived not from God but from those of us who use our agency for ill in mortal life. Unfortunately, far too many of us use it to elevate ourselves rather than our brothers and sisters.

Four Permissible Goals of Life

A Hindu may pursue four goals in life. The first two of these are self-directed. In other words, they focus on the person, while the last two are directed away from the self.

Pleasure. The first permissible goal is pleasure, but not just any pleasure. Pleasure must be pursued within the context of caste law and social propriety. While pleasure is a permissible goal, it is not the highest goal, and hopefully either in this life or in some future life people will ask if there is not a higher way. And there is.

Power or wealth. The second permissible goal is not, however, a higher way because it focuses once again on the self. The second goal is power or wealth. Again, it cannot be pursued in ways that are at variance with caste and social convention. Persons may have to be a bit thick-skinned to climb the corporate or political ladder or to gain wealth. Once again, sooner or later should come the question of whether or not there is a higher way, which, of course, there is.

Duty. The third goal begins the higher way, and it is the goal of duty. As students, for example, people owe duty to their teachers. As householders, they owe duty to their spouses, their children, aged parents, the community, an employer, the PTA, the soccer league, and any number of other organizations. Persons cease to focus on their own wants and needs and become more concerned about those of their neighbors, family, and friends.

Release. For all its good, duty is still not the highest goal of a Hindu because the ultimate goal is to break the rounds of rebirth and gain release. But this sounds rather self-directed. “I want to gain release from the rounds of rebirth.” If we think about it, however, what does release mean? It means the drop of water falls back into the ocean or the wave vanishes from the surface of the ocean and all individuality is lost. In other words, release is the ultimate of nonself, because the self is lost in the ocean of Brahman.

Four Stages of Life

Student. Just as there are four permissible goals in life, there are also four stages of life—namely, student, householder, hermit, and holy man. The stage of student is what determines whether persons are twice-born or not. Persons who are twice-born can participate in all aspects of Hindu life, including the study of sacred texts. Shudras are not spiritually mature enough to study these texts and therefore cannot be twice-born and cannot be students. Today, few actually study the religious texts as young men. Some may, but most in India study in public or private schools and thereby have moved away from the religious nature of the student stage.

Householder. The stage of householder is just what one would imagine (i.e., persons marry, have children, earn a living, care for the home, and owe responsibility to the community). The twice-born householder is expected to perform all the rituals related to various passages in life from conception to death. This is the last stage that most Hindus ever enter. The responsibilities and joys of family life are so all-consuming that there is no room for anything else. Both this stage and the stage of student are oriented toward the permissible goal of duty, since both draw people beyond themselves, although for the householder there are aspects of pleasure in marriage and family, as well as the seeking of wealth as men try to support their families.

Hermit. If persons want to pursue yet a higher goal, that of release, they must withdraw from the home and enter the stage of hermit, in which they seek to become detached from all things, be they persons, places, or things. Historically this stage has always meant that persons withdraw from society, often joining a guru in a place of spiritual retreat. There they leave their past behind, going beyond family, caste, or vocation. They are no longer who they were, since all of that was transient and impermanent.

Holy man. There is no sharp demarcation between the stages of hermit and holy man. To enter into the latter stage simply means that one has left all attachments behind and is fully focused on attaining release. They have no past, for it is gone. They have only the future hope and goal of attaining release, and many Hindus believe that when a holy man dies, he automatically gains release from the rounds of rebirth. These last two stages are not normally entered by women, although some will enter the third stage within the household, turning daily duties over to daughters-in-law while they focus on the spiritual. Almost no women enter the final stage, although there are some (few and far between) renowned female ascetics.

Latter-day Saints also have their stages of life. At eight years of age, children are baptized and are believed to become accountable for their choices. At twelve, young men are ordained to the priesthood, and young women enter the Young Women organization. At fourteen, both genders start seminary. Shortly after eighteen years of age, young men are expected to be ordained to the Melchizedek Priesthood and at nineteen to go on a mission. Girls move into the Relief Society at eighteen. At twenty-one, women may also go on a mission, if they have not yet been married. For both young men and women, normally the next stage of life is marriage and having a family while also getting an education and preparing for their future careers. This would be the householder stage. At the time of retirement, there is a stage of consecration for married couples who can once again give their lives to the church as missionaries. There is no retirement in the church.

Three Ways off the Wheel

The ultimate goal, as we have seen, is to gain release from the rounds of rebirth. This may be accomplished by following one of three paths—works, knowledge, or devotion.

The way of works. The way of works is the way that all must follow. Fundamentally it means living out individual lives within the context of caste laws, which indicate what is right and wrong for those persons. One follows his or her “way” in hopes of gaining a better rebirth in a future life. No one of any caste can escape the need to follow the route laid out by caste laws, so all castes walk this path. However, if persons are Brahmin males, another path is open to them which can lead directly to release.

The way of knowledge. The way of the Brahmin male is the way of knowledge. This is the path through which experiential knowledge of oneness with Brahman may be attained. Brahmin males held that only they had progressed sufficiently spiritually to be able to walk this path, since they had reduced karma to the degree that they were on the verge of release. The way of knowledge usually meant withdrawal into the stages of hermit and holy man, learning from a guru, and ultimately sitting in meditation that led to the experience of enlightenment, thus assuring release from the rounds of rebirth at death. As noted earlier, most Hindus assume that holy men achieve release upon death. We should probably also say here that if women want to gain release from the rounds of rebirth, it was assumed historically that eventually they had to become Brahmin males.

The way of devotion. The way of devotion was always part of the Hindu life, but it was not always viewed as a way to gain release from the rounds of rebirth. According to Brahmin males, that could be accomplished only through the way of knowledge. However, with the rise of Jainism and Buddhism, both of which offered paths to release that cut across sex and caste lines, the Brahmins validated the way of devotion to deities, which offered the same benefits as did Buddhism and Jainism but within a fully Hindu context.

Ganesha, the remover of obstacles, is one of the gods worshipped in the Hindu pantheon.

Ganesha, the remover of obstacles, is one of the gods worshipped in the Hindu pantheon.

We need to remember that the traditional goal of Hinduism was to gain release from the rounds of rebirth by gaining an experiential oneness with Brahman. However, concepts like Brahman, the wave on the ocean, droplets of water, and illusion are hard to comprehend because we try to understand the infinite with a finite mind. So, Brahman accommodates itself to our level of comprehension by manifesting itself in personal forms as creator, preserver, and destroyer. In these aspects, Brahman the infinite is known as the gods Brahma (creator), Vishnu (preserver), and Shiva (destroyer). It is through these three that the power of the devotional path of Hinduism arises.

Because these gods are aspects of Brahman or of the infinite, none of them are captured on the rounds of rebirth, and they can therefore free devotees from the realm of rebirth. Brahma is rarely worshiped by himself, and there are only two temples in all of India dedicated solely to him. He is the creator god, has essentially done his job, and is thus off on a long break. However, the two most popular male deities to whom devotion is directed are Shiva and Vishnu.

Shiva is the god of destruction and meditation. He destroys evil and ignorance particularly. Many who follow the meditative way model themselves after Shiva and devote themselves to him. A follower of Shiva can normally be identified by the horizontal stripes of white on his or her forehead.

Vishnu is the preserver deity. He preserves the earth and its people and has come in nine incarnations to preserve the world or its order. Some of those incarnations have been animal. One was a man-lion. Others were in human form, such as Rama or Krishna. Vishnu may be worshiped directly or indirectly through his incarnations.

The male deities also have female counterparts who give them power. No god has power without a female partner, and these partners may be worshiped. Through them, people can gain release because of their devotion. In addition to these male figures and their consorts, there is also Devi, the great goddess personified in Durga and Kali, both of whom strike fear into those who oppose them. Many Hindus worship them.

For those who follow the devotional way, and virtually all Hindus do so, they conceive of the god whom they worship as the god who manifests himself or herself in all the other deities. Henotheism is the name given to this practice of worshiping one god who is manifest in many other deities. The power of the devotional way is captured in the words of Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita. He says, “Be certain none can perish, trusting me. O Pritha’s son, whoso will turn to me, though they be born from the very womb of sin, woman or man; sprung of the Vaisya caste or lowly disregarded Shudra—all plant foot upon the highest path.” [7]

In other words, one does not need to be a Brahmin male to gain release from the rounds of rebirth. It can be done by becoming one through devotion with any one of the above deities who are manifestations of Brahman. Thus, as noted above, virtually all Hindus today are devotional Hindus. They worship a deity who can give them release. Even so, all must still follow the path of works, since all must live their caste laws. Some may follow the path of knowledge, living a more ascetic, meditative life and perhaps worshiping Shiva. In the end, the way of devotion is open to all.

Worship in Hinduism

To say that Hindu worship is varied is an understatement. There are probably almost as many ways of worshiping as there are worshipers, but there are some common elements that may be pointed out. The heart of Aryan worship was the sacrificial rituals that were designed to placate or please the various gods. Sacrificial rituals are still done today, generally with vegetable materials, as ways of expressing renunciation and penance. [8] Images also play a major role in Hindu worship. Some Westerners mistakenly believe the images themselves are worshiped, but they are not. They symbolize that which is divine, and they direct the worshipers’ attention in that direction. Since Brahman is viewed as being in all things, anything can be used to focus or crystallize people’s attention on god. Even a stone may represent deity, if that is the intention of the person setting up the stone. The ultimate impersonal, invisible God Brahman, may be manifest in many ways through the personalized Brahman and thus may be worshiped under many forms and names. As we have seen, Brahman can be seen as Brahma, Shiva, Vishnu, Rama, Krishna, Devi, or any other number of gods or goddesses. Since the male gods must have their female counterparts to have power, their wives may also be worshiped. For example, persons may worship Lakshmi, the wife of Vishnu, or Parvati or Durga, wives of Shiva. Most Hindus have a personal god whom they worship, and there may also be a god that is worshiped by their family to whom they submit. Simultaneously, there will probably be a local god who is worshiped. In the end, however, these are all manifestations of Brahman.

“Tools” of worship are mantras (chants), yantras (geometric pictures), and darshan (seeing the god). Chants are reality in sound. The vibrations from the chant when recited benefit both the one who recites and the hearer. They focus the mind through sound and exclude distractions as the worshiper focuses his or her mind on the reality that the sound represents, usually a god. However, the most powerful chant is simply the syllable om or aum. When pronounced properly, it captures the very essence of the universe.

Geometric pictures function in the same way that chants do, but rather than focusing the mind through sound, they focus the mind through a visual geometric representation and are often made of colored powders on the floor. The aim is to be able to visualize these and stop the flow of extraneous thoughts.

Seeing the god is also central to Hindu worship. Thus, one goes to the temple to see the god housed there. The god in turn sees the worshiper and blesses his or her life.

Ritual worship is called puja, although there are many names for worship forms. Common elements that may be observed in ritual worship are the reciting of chants inviting a particular deity to be present, the chanting of hymns of praise, and the waving of lamps, which is called arati. At the end of the waving of the lamps, worshipers will move their hands over the lamps and draw the warmth and the light to themselves, thereby being purified. At the end of worship, the priest may sprinkle the worshipers with holy water from the Ganges River.

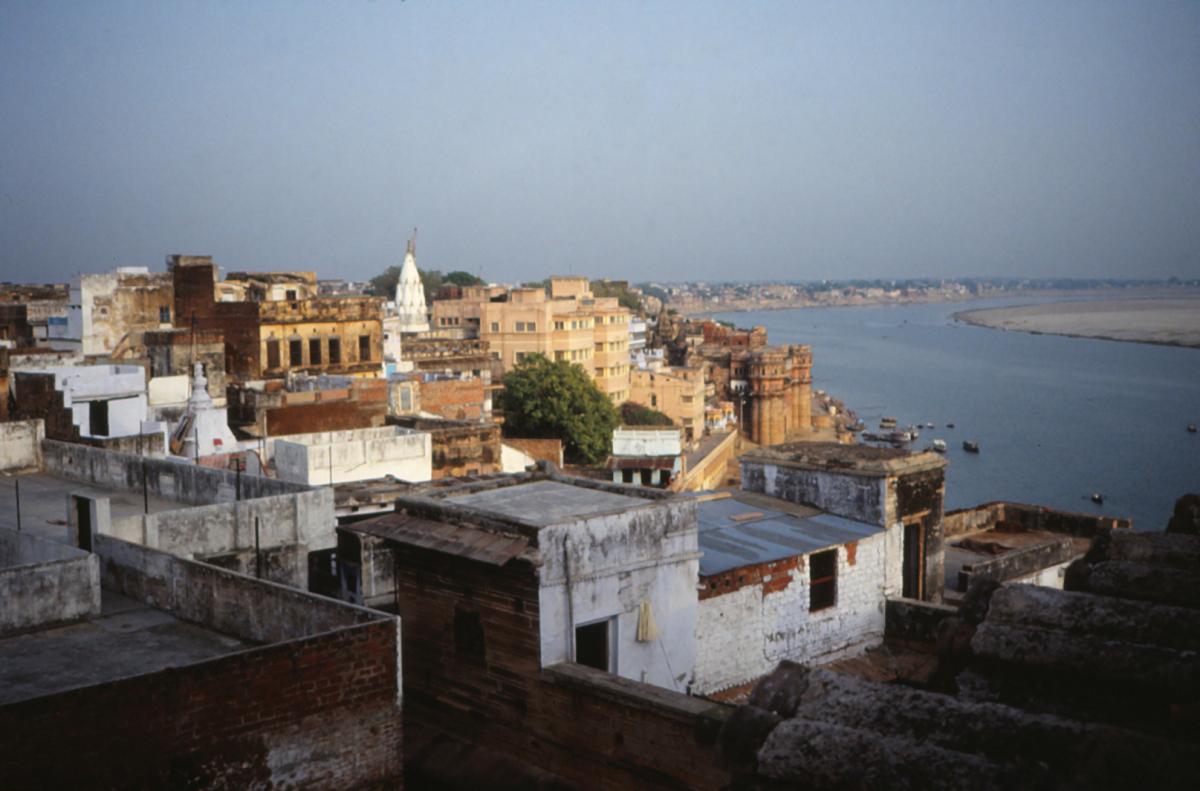

The Ganges River is considered sacred and is personified as a goddess.

The Ganges River is considered sacred and is personified as a goddess.

The most spectacular worship experience is known as the Kumbha Mela, a mass gathering that occurs four times during a twelve-year cycle. There are four sites where the Kumbha Melas are held. Up to ten million people gather at a Kumbha Mela, and the central ritual is all pilgrims bathing together in the river at a predetermined time.

Women in Hinduism

According to Sharada Sugirtharajah, society in the period of the Veda was based on the family and was patriarchal and life affirming. Initiation was open to men and women, and both could receive a spiritual education. In the realm of religious activities, men and women were equal. [9] However, with the rise of both Brahmin religious specialization and the ascetic ideal, the gap between men and women widened in society.

Historically Hinduism has been ambivalent about women, seeing them on the one hand as goddesses and on the other as temptresses. Generally, they were viewed as dependent beings for their entire lives. As girls, they were dependent on their fathers. As wives, they were dependent on their husbands, and as widows, dependent on their sons. In essence, they were not autonomous persons. When married, a woman moved into the home of her husband and became subject to his mother and other women in the household, which was often very difficult. If a husband died, the widow could not remarry, no matter how young she was. It was only in 1856 that a law was passed permitting widows to marry, although not many do so now, since it would run against custom and culture. While widowhood may be inauspicious, there is a breaking down of the public prejudice against it. For example, Indira Gandhi, a widow, was prime minister of India. However, the true feminine ideal is that of a mother, especially if she produces a son; this is because having a son will allow the family name to be continued and will thus ensure salvation of the family.

Latter-day Saints also have a patriarchal order, but it is an order shared by a man and a woman. They should be equal partners. In that partnership, both have roles that they are to fulfill—the husband is the provider and priesthood head of the home, and the wife is the primary nurturer of the family. Both roles are essential to the growing of an eternal family unit. If a man or woman loses a spouse to death, each is permitted, if not actually encouraged, to remarry. In Latter-day Saint thought, human beings were not meant to live alone.

Conclusion

Hinduism is a highly varied faith, but it is beautiful in its diversity. People seek God, and for those who live their faith well, they live very much as do Latter-day Saints with similar standards and values. These values, because they are common and good, must have their roots in a common God who is the Father of us all. Thus, he leads the Hindu toward him, just as surely as he leads the Latter-day Saint toward him, but the paths are different in external form, especially where Jesus Christ and priesthood authority are concerned.

Notes

[1] “Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents,” Adherents.com, last modified August 9, 2007, http://

[2] Swami Bhaskarananda, The Essentials of Hinduism: A Comprehensive Overview of the World’s Oldest Religion, 2nd ed. (Seattle: Viveka, 2002), 1–5.

[3] Constance A. Jones and James D. Ryan, Encyclopedia of Hinduism (New York: Facts on File, 2007), 42.

[4] Robert E. Van Voorst, Anthology of World Scriptures, 6th ed. (Mason, OH: Cengage Learning, 2008), 41.

[5] Van Voorst, Anthology, 42.

[6] B. H. Roberts, The Gospel: An Exposition of Its First Principles and Man’s Relationship to Deity, 10th ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1965), 277–79; emphasis added.

[7] David S. Noss and John B. Noss, A History of the World’s Religions, 9th ed. (New York: Macmillan College, 1994), 133.

[8] Anuradha Roma Choudhury, “Hinduism,” in Worship, ed. Jean Holm with John Bowker (New York: Pinter, 1994), 64.

[9] Sharada Sugirtharajah, “Hinduism,” in Women in Religion, ed. Jean Holm with John Bowker (New York: Pinter, 1994), 59–60.