The Testimony of Alma: “Give Ear to My Words”

John W. Welch

John W. Welch, "The Testimony of Alma: 'Give Ear to My Words,"' Religious Educator 11, no. 2 (2010): 67–87.

John W. Welch (WELCHJ@lawgate.byu.edu) was the Robert K. Thomas Professor of Law at the J. Reuben Clark Law School at Brigham Young University when this was written.

Address given at Campus Education Week in August 2003 and rebroadcast on KBYU and BYUTV.

Minerva K. Teichert, An Angel Appears to Alma and the Sons of Mosiah, ca. 1935, oil on masonite, 36 x 48 inches, Brigham Young University Museum of Art, gift of Minerva K. Teichert, all rights reserved.

Minerva K. Teichert, An Angel Appears to Alma and the Sons of Mosiah, ca. 1935, oil on masonite, 36 x 48 inches, Brigham Young University Museum of Art, gift of Minerva K. Teichert, all rights reserved.

"The angel of the Lord appeared unto them; and he descended as it were in a cloud; and he spake as it were with a voice of thunder, which caused the earth to shake upon which they stood" (Mosiah 27:11).

I am humbly grateful for the invitation to share with you a few thoughts about the wonderful words and inspiring testimony of Alma the Younger. I am amazed and enriched by the words of this truly towering figure in the Book of Mormon. I share the feelings of Elder L. tom Perry, who has written, "Alma the Younger has been a special favorite of mine." [1] I hope to do some small justice to a few of his exquisite words

In Alma 36, at the very beginning of his masterful blessing to his firstborn son, Helaman, Alma admonished, “My son, give ear to my words” (v. 1). We would all do well to follow this counsel, to give special heed to the powerful testimony of Alma, and to recognize the doctrinal purity and power that permeates the texts of this remarkable father, teacher, prophet, high priest, chief judge, governor, soldier, and record keeper. It is hard to say enough about this spiritual, dynamic, and articulate disciple of Jesus Christ.

Alma truly knew his Savior, the coming Redeemer, the Good Shepherd, who still stands at the head of his flock today. We should bear in mind that Alma paid the price for this knowledge. He made significant sacrifices. For example, he left the most powerful position in his society to become a humble full-time missionary, going at one time to the apostate city of Antionum when he himself was feeling "infirm," perhaps due to his failing health or some chronic malady. I stand in awe of the risks that he took in the gospel's behalf, especially when he was all alone, with no companion or bodyguard, right into the jaws of absolutely certain hostility in the city of Ammonihah, the hotbed of Nehorism, not long after he himself as the chief judge had personally ordered the execution of Nehor. Going into this city, he fasted and prayed many days over the sins of his people, to the point of such great hunger that it led to angelic intervention (see alma 10:7). I am also struck by all that had to transpire that we might have these precious words. I can only imagine the laborious efforts he and others undertook to record and preserve the speeches of this great leader in an era when writing such things was not a simple task. Remembering these sacrifices helps me treasure the se words all the more.

The speeches of Alma in the Book of Mormon are among the very richest chapters of the entire book. I think it is fair to call them a doctrinal epicenter of the Book of Mormon. Alma’s words bear repeated dissection, and they reward persistent pondering. I know that, like most of the Book of Mormon, the words of Alma will wear me out long before I wear them out.

Alma the Younger, of course, is best known for his unforgettable conversion story, rendered very sensitively by the artist Minerva Teichert, whose depiction I think clearly communicates the merciful holiness of the powerful angel of the Lord who appeared to the wayward young man and the four sons of Mosiah. As Elder Jeffrey R. Holland has said, " The life of the younger Alma portrays the gospel's beauty and reach and power perhaps more than any other scripture. Such dramatic redemption and movement away from wickedness and toward the permanent joy of exaltation may not be outlined with more compelling force anywhere else." [2]

But beyond his conversion, Alma became a strong public servant and influential political figure in Nephite civilization. In a way, Alma was the John Marshall of his day. Like Marshall, the formative chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, Alma served as the inaugural chief judge under the new Nephite legal system of the reign of the judges. He would also become a sort of Winston Churchill of his people, holding Nephite society together at a time of civil war, personally going out in one-on-one hand-to-hand combat against the arch-kingman Amlici; Alma’s words and deeds successfully galvanized the Nephites and led them to victory as Churchill did for the Allies in World War II.

At the same time, Alma went on to become a great prophet. He suffered the refining agonies of prison confinement, much as the Prophet Joseph did in Liberty Jail. Here you see Teichert's depiction of Alma's and Almulek's miraculous liberation from prison after enduring many days of brutal confinement.

Concurrently, Alma became something of the Thomas Aquinas of the Nephite world— his theological discourses, especially my favorites Alma 13 and 42, are among the richest doctrinal expositions in scripture. Alma persuasively articulated truth as he confronted formidable theological opponents—from the priestcrafty Nehorites and the Rameumpton-building Zoramites, to the logician Zeezrom and the philosophizing Korihor. Readers should approach Alma’s intellect and his keenly chosen words with the same receptive respect one uses in approaching the words of the greatest masters in world literature. In 1997, Noel Reynolds and I were able to participate in a private weeklong scholarly conference, which was organized by an exclusive non-LDS thinktank, in order to study the political theory implicit in the Book of Mormon’s teachings about liberty. After several days of intense scrutinizing, scholars who for the first time encountered the brilliant discourses of Alma expressed high regard for the depth and power of his compelling insights.

For these and many other reasons, understanding Alma is crucial to any understanding of the Book of Mormon. He is central. King Benjamin's speech is phenomenal, yet only one speech, given on one occasion, the coronation of Mosiah the Second, and is encompassed in only four chapters. Of Alma we have ten speeches, comprising over sixteen chapters, not to mention several other shorter Alma texts. These words are treasures of spiritual literature standing at the core of the Book of Mormon.

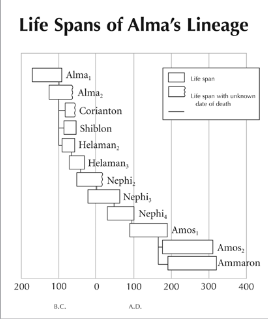

The testimony of Alma is indeed the spinal cord that runs through the backbone of Nephite prophetic history. Genealogically, we have an interesting situation here, with Alma standing in a position that we do not often appreciate, as you will see on this chart.

| Alma's Family Line |

|---|

| Alma the Elder |

| Alma the Younger |

| Helaman |

| Helaman |

| Nephi |

| Nephi |

| Nephi |

| Amos |

| Amos-Ammoron |

This chart shows the lineage of Alma and approximate life spans of him and his descendants mentioned in the Book of Mormon.

This chart shows the lineage of Alma and approximate life spans of him and his descendants mentioned in the Book of Mormon.

He is the son of Alma, the priest of Noah who was converted by Abinadi. We don't know when Alma the Younger was born, but since he was still a young man at the time of his conversion, it was probably between 95-100 BC. He probably wasn't born much before 125-120 BC, right around the time that his father's covenant community rejoined the Nephites in Zarahemla. Alma the Younger has three sons: his oldest is Helaman, who will become the leader of the stripling warriors about ten years after Alma's mysterious departure. Helaman's son, Helaman, is after whom the Book of Helaman is named. The son of Helaman is Nephi, the one who goes with his brother Lehi and converts the Lamanites in the miraculous episode reported in Helaman chapter 5. His son is another Nephi, the one after whom the book of 3 Nephi is named, who prays that the Lord will come on the morrow. And after that Nephi we have his some, another Nephi, who begins the book of 4 Nephi, and then the plates pass on to his son Amos, to his son Amos, and to his brother Ammaron, who is the one who gives all of the plates and Nephite sacred artifacts to Mormon. So, in a sense, Mormon got the plates from Alma. It was Alma the younger who received the plates and sacred implements from King Mosiah, the last kind before Alma became the chief judge. Can you see why one may call Alma and his lineage the backbone of the Book of Mormon? This point might also explain why Mormon and the Nephite record keepers took special efforts to preserve the speeches of Alma, their most illustrious ancestor. He is the linchpin in the main line of Nephite prophets all the way down until the virtual end of their civilization

In light of the importance of his texts, I wish to examine four sources of power in the words of Alma the Younger; I hope that these four points will help you gain greater appreciation and understanding of his words and testimony. First, I will show how he speaks with an authentic voice of true personal experience. Second, he knows his audiences and tailors his words to meet their particular needs and circumstances. Third, he makes very skillful and creative use of language and literature. And fourth, he bears open testimony of his deepest spiritual desires and of vital eternal truths.

1. Alma speaks with the authentic voice of personal experience.

In commenting on ways in which Alma's words subtly and authentically reflect his unique persona, we enter a fascinating field. in a moving article about Alma's totally repentant transformation, published in the March 1977 Ensign, Elder Holland invites us into the life of this engaging person: there is so much that should be said of him; his political role, his high priestly power, his missionary trials, his concern for his sons. He saw people repent at great social and political cost. Some paid with their very lives...he taught deep doctrines, he lived by sublime personal values, and he rejoiced in his own missionary success and the success of his brethren...All this came after his willingness to undergo...the monumental process of the soul called repentance."[3]

We are the great beneficiaries of Alma’s remarkable candor about his own mistakes and successes. Alma spoke as a personal witness and bore personal testimony of the things that he had experienced and learned. As a writer, he does not hold back from us his personal character. He lets it spill out. As a speaker, he is personal and intimate. If we are receptive readers, we can know this man. We can see his character as he shares with us his innermost thoughts.

Take Alma 5 as an example. In this speech he pours out his feelings. He says, "I speak in the energy of my soul"(v.43). "I do know that these things whereof I have spoken are true. And how do ye suppose that I know of their surety?...They are made known unto me by the Holy spirit of God. Behold I have fasted and prayed many days that I might know these things of myself, And now I do know of myself that they are true"(vv.24-46). Not all speakers are as intimate and personal with their audience as Alma. He is not afraid to stand up and share his personal experiences. That openness gives his words power. That forthrightness lets people know exactly where he stood. You never are in doubt about where Alma stands on the gospel of Jesus Christ. He does not mince words. his speeches reflect his real life, and in doing so they reflect the truth in a very powerful, personal way.

Each prophet, of course, has his own personality. Their personalities come through in their vocabulary, out of their life experiences, and through the concerns that deeply drive them. The prophet Jeremiah was different from the prophet Isaiah. President Brigham Young’s personality was different from President David O. McKay’s. In Alma’s case, consider two key parts of his life that distinctively give extraordinary power to his words: his conversion, and his work as a jurist.

The crux of Alma's life came, and as he tells in Alma 36:18, when he remembered, in his moment of darkest distress, that his father had spoken of one Jesus, a Son of God who would come to atone for the sins of the world, and he cried out, "O Jesus, thou Son of God, have mercy on me, who is in the gall of bitterness." He never forgot that moment. The mercy that was shown to him in his desire to repent (otherwise unworthy as he was) became the driving characteristic of his total existence. If you listen carefully, you can hear echoes of this life-changing moment throughout his speeches, as Professor Kent Brown has shown in his study published in the 1992 Sperry Symposium volume. For example, we all remember Alma's soliloquy in Alma 29, " O that I were an angel" and could speak " as with the voice of thunder," "with a voice to shake the earth, and cry repentance unto every people." (vv.1-2). What we don't often think is this: Alma is thinking and talking here about that very angel who appeared to him, with a voice of booming thunder that shook the earth and urgently cried repentance to him. Alma wants to be like that angel! Professor Brown was right: The similarities between the angel of Alma's conversion and the angel of Alma's yearning "cannot be missed." [4]

That conversion experience was real. That reality surfaces again and again. As I have charted out elsewhere in print, subtle linguistic evidence makes it apparent that Alma’s three accounts of his conversion in Mosiah 27, Alma 36, and Alma 38 all originated from the same man.[5] Remarkably, even though these tellings come from three different times or stations in Alma’s life, and even though they are separated in the Book of Mormon by many words, events, conflicts, and distractions reported in more than a hundred pages of printed text, Alma’s distinctive words and phrases come through loud and clear, bearing the unmistakable imprints of a single distinctive person. His conversion story becomes the heart of his farewell testimony to his son Shiblon in Alma 38, who, Alma reminds, had been delivered by God from bonds and stoning at the hands of the Zoramites just as Alma had been delivered from his own spiritual bondage and work of destruction. His conversion stands behind his words of warning to the people in Ammonihah that they will be utterly destroyed if they, as he had once done, sought to “destroy his people” (9:19); and again, the “marvelous light” (36:20) of that conversion stands behind his encouragement to the poor in Antionum, who are told that they can plant the seed of truth, feel it swell, and taste its light and know as he came to know that the truth is good and that it is real (32:35). In these and many other ways, Alma’s indelible conversion gives his words potent credibility as he speaks incessantly from this platform of real personal experience.

Because of his own deliverance, alma repeatedly testifies that there is no other way by which we can be saved than through the atoning blood of Jesus Christ. In his sermons, you can find him speaking of the merciful deliverance on at least twelve major occasions. The crux of Alma 7 deals with the deliverance of the Atonement, with the suffering that Christ bore, painfully reminiscent of alma's own bitter suffering that racked him with eternal torment and pain. The plan of redemption is again a major theme in Alma 12-1, when he himself is in dire need of deliverance from prison in Ammonihah and again in Alma 33, where he appropriately quotes to the Zoramites the words of Zenos, who like them had himself been excluded from places of worship yet knew how to pray to and be heard by his Redeemer. Over and over, the atoning Christ, who joyously brings deliverance, is the central figure in the concerns of Alma. We misread Alma if we do not see his words against the setting of his personal experiences of deliverance.

Because of his own fortuitous redemption, Alma’s character is infused with patience and generosity toward others. He generously dedicated himself to proclaiming the word, because, as he says in Alma 6:5, “the word of God was liberal unto all.” Alma turned no one away. He went to the poor, to the rich, to his enemies, to his friends. He would give them anything, for he personally had been given much.

But Alma was also a jurist, for whom mercy could not rob justice. Together with his legal personality came a strong sense of justice and accountability. He knew that people are responsible for their actions. Alma was an experienced judge. Professionally, he was the highest jurist in the land. he served as chief judge for eight formative years, working long hours, being involved in landmark cases such as he trials of Nehor, and Korihor, with himself on trial in Ammonihah. You can take Alma off the bench, but you can't take the bench out of Alma.

| Legal Themes in Alma’s Speeches |

|---|

| Standing before the judgment bar of God (Alma 5) |

| Basis of God’s judgment (Alma 12) |

| Concept of restorative justice (Alma 41) |

| Operation of justice and mercy (Alma 42) |

Thus, when Alma speaks of the judgment of God, he speaks with legal experience. In at lease ten passages, you can find Alma talking about God judging his people. for example, Alma describes what it will be like when we stand before the judgment bar of God in Alma 5: 15-23, he devotes nine verses to describing how we will feel standing before God as our judge. He asks: When we look up to God in that day, "do ye imagine to yourselves that ye can lie unto the Lord in that day, and say--Lord, our works have been righteous works upon the face of the earth--and that he will save you? Or otherwise, can ye imagine yourselves brought before the tribunal of God with your souls filled with guilt and remembrance of all your wickedness, yea, a remembrance that ye have set at defiance the commandments of God?" This sounds to me like a judge speaking to us, like a person who has had actual people standing before him, waffling, trying to lie, trying to misrepresent, but feeling shame and knowing full well that they must be held accountable for what they have done.

Judge Alma is the one who tells us most explicitly in Alma 12:14 the three evidentiary grounds on which we will be judged: by our words, our deeds, and our thoughts. He says, “For our words will condemn us, yea, all our works will condemn us; . . . and our thoughts will also condemn us, and in this awful state will shall not dare to look up to our God; and we would fain be glad if we could command the rocks and the mountains to fall upon us to hide us from his presence.”

| The Speeches of Alma | ||

|---|---|---|

| Reference | Topics | Audience setting |

| Mosiah 27:24-31 | Alma's conversion | those assembled to pray for Alma |

| Alma 5 | true conversion | backsliding church members in Zarahemla |

| Alma 7 | atonement | righteous people in Gideon |

| Alma 9 | repentance and deliverance | wicked people in Ammonihah |

| Alma 12-13 | the plan and holy order of God | wicked people in Ammonihah |

| Alma 29 | "O that I were an angel" | unknown |

| Alma 32-33 | humility, faith, prayer, atonement | the poor outcasts in Antionum |

| Alma 36-37 | Alma's conversion, following the Lord | his son Helaman |

| Alma 38 | Alma's conversion, wise counsel | his son Shiblon |

| Alma 39-42 | sin, redemption, justice, mercy, resurrection, restoration | his son Corianton |

Again, it is Alma the judge who articulates the meaning of restorative justice in alma 41. He explains that the meaning of the word restoration is to bring back good for that which is good; evil for that which is evil; devilish for that which is devilish. The restorative concept, which epitomized the ancient Israelite eye-for-eye, bruise-for-bruise rubric of talionic justice, the undergirded Hebrew law in biblical times, as Alma would well have known.

Strikingly, it is no surprise that it is judge Alma, of all the prophets, who wrestles most of all, particularly in Alma 42, with the tension between justice and mercy. After all, as a judge he had been required both to apply the demands of the law and also to consider the petitions for mercy in a number of very hard cases. Getting justice and mercy together is the ever-present task of every good judge.

Like a judge or lawyer, Alma also knows how to ask the penetrating questions. In Alma 5 alone, I count fifty questions that he asks, one after another: " Can ye look up, having the image of God engraven upon your countenances?"(5:19). "Can ye feel so now?"(5:26). "have ye walked, keeping yourselves blameless before God?" (5:27). "Are ye stripped of pride?" (5:28). "Of envy?" (5:29). "Of what fold are ye?"(5:39). his questions go on and on, extremely effectively. as I give ear to his words, I feel like I'm being cross examined by a masterful jurist who knows how to ask me exactly the right questions.

2. Alma knows his audiences and tailors his words to their needs and circumstances.

It helps us give ear to Alma’s words when we see how sensitively he spoke to each of his particular audiences. Because we know that he spoke so personally to them, we can hear him speaking personally to us, as we too share many of the recurring concerns and persistent predicaments felt by those Nephite audiences.

Consider the audience's role in each of his ten main texts.

| Audiences Addressed by Alma | |

|---|---|

| Mosiah 27 | To his family and friends |

| Alma 5 | To church members in Zarahemla |

| Alma 7 | To righteous members in Gideon |

| Alma 9 | To wicked people in Ammonihah |

| Alma 12–13 | To his accusers in Ammonihah |

| Alma 29 | To himself in prayer to God |

| Alma 32–33 | To the poor outcasts in Antionum |

| Alma 36–37 | To his righteous son Helaman |

| Alma 38 | To his second son Shiblon |

| Alma 39–42 | To his wayward son Corianton |

First we have his spontaneous conversion speech in Mosiah 27, where he stands up and addresses his family who have fasted and prayed over him for three days and three nights. he knows how much they had worried about him, before and during this ordeal. He addresses their concerns using straightforward, graphic terms that must have been both relieving and astonishing to them, telling them exactly what had happened to him in the amazing reversal that he has just experienced. His style here is succinct and declarative.

Next we have Alma 5. Here Alma is speaking to backsliding church members in the city of Zarahemla. Remember that there had been 3,500 converts the year before. It had been a great, successful year for the missionary effort following the defeat of Amlici. But Alma had a retention problem; perhaps some had joined for social or political reasons in the aftermath of the civil war. In this setting, Alma delivers a classic covenant renewal speech, encouraging people to renew or to deepen the level of conversion they had previously experienced. Here his style is authoritative, drawing heavily on phrases from King Benjamin’s renewal text given in the same city of Zarahemla forty-two years (or six sabbatical periods) earlier.

In Alma 7, Alma speaks to the righteous people in the new city of Gideon. These people were probably children of the immigrant people of Limhi, for they named their city after Gideon, who was Limhi's captain who had been killed by Nehor. Thus, their fathers had been rescued from captivity and suffering themselves, and they must have sought solace concerning the death of their friend and hero Gideon. In this setting, alma focuses on the Atonement of Jesus Christ, a message that would have spoken deeply to these faithful souls as he told them that Christ would "take upon him their infirmities, that his bowels may be filled with mercy, according to the flesh, that he may know according to the flesh how to succor his people according to their infirmities" (7:12). Here Alma's style is consoling and sympathetic as he makes a special point of reaching out to them personally in his own language or dialect.

In Alma 9, we encounter a totally different mood. Alma boldly delivers a pure prophetic judgment speech to the wicked people of Nehor in the land of Ammonihah. Here Alma focuses on repentance and how God will deliver people only if they properly repent; otherwise they are ripe for destruction. His style is blunt and consequential.

Alma chapters 12 and 13 comprise two of the most powerful chapters in all of the Book of Mormon, dealing with the plan of salvation and the holy order of the Melchizedek priesthood prepared from before the foundation of the world. After being in prison for about three months, Alma took this one last opportunity to understand the true plan of redemption and the eternal powers of the ordinances of the priesthood. Nehorites specifically rejected the Nephite doctrines on sin and priesthood, so Alma addresses precisely these two topics, meeting his Nehorite challengers squarely on the issues most vital to them, as well as to us. His words here are deliberative, freighted with ritual allusions and cosmic symbolism.

In Alma 29, Alma’s primary audience is himself. Who can fail to sense his sincerity as he ponders the wish and prayer of his heart: “O that I were an angel” (v. 1). We will come back to this interior text.

Alma 32–33, on planting the seed of faith and nourishing its growth, are words tailored exactly to the needs of the poor outcasts in Antionum who had built the synagogue, in which the Zoramite leaders would not let them worship. Here Alma uses the imagery of planting and nourishing a seed to reap a glorious harvest, something that even the poorest peasant farmer among them would readily understand. His themes are humility, faith, prayer, and coming unto Christ. His style is empathic and invitational.

Alma chapters 36–42 preserve Alma’s words to his three sons, Helaman, Shiblon, and Corianton. How different the blessings and instructions are to each! There is nothing trite or rubber-stamped here. Alma was a good father; he knew each of his sons personally. He had taught and worked with them. Helaman, the responsible oldest son, suitably received the firstborn’s doubled blessing (twice the length of Shiblon’s) and is charged with the duty of keeping the records. Shiblon, a middle son, receives wise social counsel: “use boldness, but not overbearance” (38:12), “see that ye bridle all your passions, that ye may be filled with love; see that ye refrain from idleness” (38:12–13). Corianton, the wayward son, is told of sin, abomination, crime, resurrection, restoration, and judgment in words that would set his teeth on edge as the Hebrew father was told that he should speak at Passover to a son in need of censure and repentance.

From this brief survey, I hope you will agree that we have our work cut out for us as we strive to hear the rich and manifold tonalities in each of Alma's speeches. We give sharper ear to his carefully tailored words when we hear them through the ears of his audiences. And speaking of Alma's carefully crafted words, let us turn to my third point.

3. Alma makes very skillful and creative use of language and literary forms.

Alma is obviously a very skillful writer. He was gifted with words from the time of his youth. When Mosiah 27 describes Alma and the four sons of Mosiah who caused so many difficulties for Alma’s own father and the Church, it notes that Alma was adept at flattering the people with his words. He was a skillful orator. He knew how to use words. That was how he was able to cause so many problems. After his conversion, he employed that impressive talent in the work of the Lord. Let’s look more closely to better appreciate a few of the amazing compositional qualities of Alma’s words.

Alma was precise with individual words. For example, in Alma 36, as Alma strives to communicate the ecstasy he felt at the joy of his conversion, he quotes Lehi when he says, “Yea, methought I saw, even as our father Lehi saw, God sitting upon his throne, surrounded with numberless concourses of angels, in the attitude of singing and praising their God; yea, and my soul did long to be there” (36:22). Twenty-one words are quoted precisely, absolutely perfectly, from the words of Lehi in 1 Nephi 1:8. This tells us that Alma knew his scriptures by heart. He could quote them vertabim (as he also quoted the words of Zenos spontaneously in Alma 33:4–11). By the way, if you think about it, this precision also bears strong evidence of the miraculous nature of Joseph Smith’s translation. I doubt that, in translating Alma 36, Joseph said to Oliver, “Please read back to me what we had Lehi say in 1 Nephi chapter 1. I want to get the quote exactly right.” I think that if he had said this, Oliver would have walked off the job.

In addition, Alma was meticulous about his cumulative and collective words. Certain words seem to have been measured and counted. We spot this trait in Alma 31: 26–35, when Alma prayed before entering the Zoramite city of Antionum. In that prayer he invoked the sacred name “O Lord” exactly ten times. It seems more than coincidental that ten is the traditional ancient number of perfection, an especially suitable number of times for uttering the holy name of God. That Alma would invoke the divine name ten times seems hardly accidental.

Alma was also skillful in sentence composition. He made brilliant use of antithetical parallelisms.

| Antithetical Parallelism in Mosiah 27:29–30 |

|---|

|

I was in the darkest abyss; But now I behold the marvelous light of God. My soul was racked with eternal torment; But I am snatched and my soul is pained no more. I rejected my Redeemer, and denied that which had been spoken . . . ; But now that they may foresee that he will come and that he remembereth. . . . |

In Mosiah 27 we find the words that he spoke right after his conversion. Just liberated from three days of torment and finding his whole life changed, he speaks in a spontaneous style: I was this, but now I’m that. I was this, but now I’m that. We find these antithetical parallelisms especially in verses 29 and 30. Let me emphasize them: “I was in the darkest abyss; but now I behold the marvelous light of God. My soul was racked with eternal torment; but I am snatched, and my soul is pained no more. I rejected my Redeemer, and denied that which had been spoken of by our fathers; but now [I affirm] that they may foresee and that he remembereth every creature of his creating.” These back-and-forth statements are called antithetical parallelisms: they are typically pairs of abrupt, short statements that work as good one-liners. They are especially suitable in showing surprise such as Mosiah 27.

Alma also made skillful use of complex structural chiasmus or inverted parallelism. This is the style of writing that presents a series of words in one order (A-B-C) and then turns around and presents them in the opposite order (C-B-A). Chiasmus is not completely unique to Hebrew literature, but its use is an indication of Hebrew style. A good example of chiasmus is found in Leviticus 24:13–23. Alma, as a close student of scripture, may have learned this writing technique from passages such as that one on the plates of brass.

Alma chapter 36, the entire chapter, is the best example of chiastic writing that I know of anywhere in the Book of Mormon or, for that matter, in world literature. It tells the same conversion story as does Mosiah 27, but now, with more time to structurally formalize his words, Alma takes all of the antitheticals and packs the bad things—I was this, I was this, I was this—in the first half of Alma 36, and then puts all the good things—now I am this, I am this, I am this—in the second half of the text. Using his own voice and original words, he has rearranged his initial spontaneous words into a masterful inverted parallel structure. You see here only the center elements in the overall chiastic structure of Alma 36.

| Chiastic Centerpiece of Alma 36 |

|---|

|

Lost the use of his limbs (v. 10) Feared to be with God (v. 15) Was harrowed up by the memory of his sins (v. 17) Remembered Jesus Christ, a Son of God (v. 17) Cried, “Jesus, thou Son of God” (v. 18) Was harrowed up by the memory of his sins no more (v. 19) Longed to be with God (v. 22) Received the use of his limbs (v. 23) |

The rest, we might say, is literature. Alma 36 is truly an impressive utilization of chiastic composition. Not only these center verses, but the entire chapter is structured chiastically, making it one of the longest chiasms you will find anywhere. Its degree of balance is also very remarkable. The center is right in the middle: 52 percent of its words precede this turning point, 48 percent are behind it. Twenty-five of its words appear exactly twice in the chapter: once in the first half and once again in the second half. After reading through this chapter with me, a famous scholar of Old Testament Yahwistic poetry smiled and said, “Mormons are very lucky. Their book is truly beautiful.”

And more than that, Alma uses chiasmus not just as a literary device but to focus attention on the critical turning point of his life. Chiasmus is the best literary form with focusing power. From these pivotal words, we can see the real pivot point of Alma’s life. It wasn’t the coming of the angel, where we might put it. The turning point of Alma’s life was three days later. “I remembered also to have heard my father prophesy unto the people concerning the coming of one Jesus Christ, a Son of God, to atone for the sins of the world. Now, as my mind caught hold upon this thought, I cried within my heart: O Jesus, thou Son of God, have mercy on me, who am in the gall of bitterness” (vv. 17–18). He even makes the structural contrast explicit: “Yea, my soul was filled with joy was as exceeding as was my pain” (v. 20), as if to say, “Get the point. I’m comparing the two. You can’t understand the one without the other.” Alma uses chiasmus as an effective focusing tool that embraces this entire chapter, which begins and ends with related words: “My son, give ear to my words” (v. 1) and “now this is according to his word” (v. 30), marking the boundaries of this textual space.

This was one of the first chiasms I discovered in the Book of Mormon as a missionary in 1967 and published in 1969 in BYU Studies. It remains one of my favorites. According to a recent statistical analysis by Boyd and Farrell Edwards in BYU Studies, the odds of this central configuration occurring by chance are minuscule.[6]

Alma was also creative with his words. Perhaps the most clever use of chiasmus is found in Alma 41:13–15. In speaking to Corianton, as we mentioned previously, Alma had to explain the meaning of the word restoration. The Nehorites taught that all people would be restored to a condition of happiness. Alma had to explain that the meaning of the word restoration is to bring back “good for that which is good, righteous for that which is righteous, just for that which just, merciful for that which is merciful.”

| First a List of Pairs | |

|---|---|

| Good | Good |

| Righteous | Righteous |

| Just | Just |

| Merciful | Merciful |

| Then a Pair of Lists |

|---|

|

Merciful Justly Righteously Good Mercy Justice Righteous Good (Alma 41:13–15) |

Then, as it appears in the English translation, he says: “Therefore, my son, see that thou art merciful unto your brethren, deal justly, judge righteously and do good continually.” Notice that he had said, “You will get a good reward if you are good; therefore be good.” But after having said only that much, the pattern is unbalanced. He has mentioned good, righteous, just, and merciful twice in the first list of pairs; and thus far he has only given that list once in the opposite order. So he continues: “And if ye do these things, ye shall have your reward.” He goes through the same four, again, in the opposite order: “Ye shall have mercy restored unto you again, you shall have justice restored unto you again, you shall have a righteous judgment restored unto you again, and you shall have good rewarded unto you again.” He has given us a list of pairs and then a pair of lists in the opposite order. This is very clever.

But again, the form of this passage is not just ornamental. Alma’s creative use of chiasmus in Alma 41 perfectly communicates the essence of restorative justice, namely that God’s justice will be balanced. As in Leviticus 24, the use of chiasmus in Alma 41 communicates the essence of ancient Israelite jurisprudence: bruise for bruise, tooth for tooth; or in other words, let the punishment match the crime. So the use of chiasmus in Alma 41 serves Alma’s needs beautifully and also gives us an exquisite example of this style of writing. Research has shown that some people knew about chiasmus in Joseph Smith’s day, although there is no indication that Joseph himself was aware of it; and even so, knowing a few of its rudiments is one thing; producing creative masterpieces of this quality is a very different matter.

4. I would conclude by giving ear to ten points as Alma bears open testimony of his deepest spiritual desires and of vital eternal truths.

Let’s turn particularly to Alma 29 and try now to give special ear to his words in these ten respects:

1. Let us appreciate the intensity with which Alma says, “I would declare unto every soul, as with the voice of thunder, . . . that they should repent and come unto our God, that there might not be more sorrow upon all the face of the earth” (Alma 29:2). Repentance is the key for us all, if we are to eliminate sorrow in our own lives or in the world around us. Alma 29 was written very shortly after one of the most sorrowful days in Alma’s life. Thousands of bodies were laid low in the earth (see Alma 28:11). The Nephites had fought a vicious battle in the defense of the rights of Ammonite converts to stay in the land of Zarahemla. This was a bittersweet time in Alma’s life. He felt the pain, the cost that had been paid by those soldiers and their families. Alma also knew the price that the Ammonites had paid to become converts to the Church. He also had witnessed up close the cost that Amulek had recently borne as the men in Ammonihah cast out the believing men and burned their books, along with their women and children. Among those women and children, would there not have been Amulek’s own wife and children? Alma knows that all this sorrow could have been averted by a willingness of some to repent. Helping someone to repent from day to day may be the most important function and operation of the priesthood. Alma looked up especially to Melchizedek as the greatest high priest, and why? Because when Melchizedek preached repentance to his people, they did repent, perhaps the most desirable priesthood miracle of them all.

2. Alma continues in 29:3–4, “But behold, I am a man, and do sin in my wish; for I ought to be content with the things which the Lord hath allotted unto me.” What’s wrong with Alma’s wish? He goes on to explain, “I ought not to harrow up in my desires, the firm decree of a just God, for I know that he granteth unto men according to their desire, whether it be unto death or unto life.” Alma knows the eternal truths that God is in charge; that he has allotted certain roles, callings, situations, or challenges to each of us; and that he will give everyone their free agency to choose in those roles the path of death or the path of life. Much of happiness is found in being content with whatever our just Lord has willed for us.

3. Let us give ear as he goes on in verse 5, “Yea, and I know that good and evil have come before all men; he that knoweth not good from evil is blameless.” We might ask, Is this Alma the lawyer again, thinking of them as acquitted from guilt? He continues, “But he that knoweth good and evil, to him it is given according to his desires, whether he desireth good or evil, life or death, joy or remorse of conscience.” Alma knows that opposition is in the very nature of this creation. As Alma grew older, things seem to have become even more black and white for him. This happens when we see things more in an eternal perspective: areas of gray become less significant. Ultimately, things either build up our desire in favor of the kingdom of God or take away from it.

4. What do we hear in verses 7 and 8 where he then asks, “Why should I desire that I were an angel, that I could speak unto all the ends of the earth? For behold, the Lord doth grant unto all nations, of their own nation and tongue, to teach his word, yea, in wisdom, all that he seeth fit that they should have”? Alma knows that the Lord will grant unto all nations the level of wisdom that they need. Throughout his speeches, Alma knows that we grow in knowledge incrementally. As a seed grows, we become perfect in that one thing, and then we go on to the next. For Alma, perfect knowledge is not received in a single chunk. Instead, God gives to each person incrementally the amount that he or she is to have at this time, according to the heed and diligence that each person is willing to bring to bear.

5. Alma knows that we grow not only in knowledge of that which is just and true but also in a knowledge of that which is good. Notice and give ear to Alma’s particular words here. It is one thing to know that something is true, another thing to know that it is good. When the seed begins to grow, I think it is significant that the first thing that a person knows, in Alma 32:33, is that the seed is good. Indeed, Satan knows a lot of truth; he is very smart. But what Satan doesn’t know or won’t respond to is that which is good. Hitler knew a lot of truth, but what he didn’t know was how to put that knowledge of mathematics, communications, or economics to work for good purposes. I think Alma wanted us to know that the gospel is both true and also that it is good.

6. Next in Alma 29:9, Alma’s testimony turns to sharing his joy: “And this is my glory, that perhaps I may be an instrument in the hands of God to bring some soul to repentance; and this is my joy.” Alma knows that joy is found in helping others, especially in helping them fulfill eternal needs. If you ever feel sad or sorry for yourself, follow Alma’s pattern. Go out and do your visiting teaching or your home teaching; find a way to help someone repent. There you will find joy, as he did.

7. Do we give ear as Alma reminds us that we must remember what the Lord has done? When he sees others truly penitent, then he remembers “what the Lord has done for me, yea, even that he hath heard my prayer; yea, then do I remember his merciful arm which he extended towards me” (v. 10). Remembering is a spiritual process. Remembering is to the past as faith and hope are to the future. It is significant that we make only one promise as we partake of the sacrament, namely that we will remember him always.

8. Alma remembered specifically that he had been heard of God. He testifies that God will hear the words of our mouth. Let us listen carefully here. There is an upside to this and a downside as well. Sometimes we only want God to hear our prayers when we are taking a test or find ourselves in great need. Perhaps on a Friday night or off at a party, we’d rather not have God listening in to what is going on. But Alma learned that God heard him even in his most rebellious moments.

9. Alma ends his testimony in chapter 29 by speaking of the fruits of joy and happiness that will come by planting and cultivating a particular word that will spring up in us unto eternal life. He is carried away with joy because he had been called “by a holy calling, to preach the word” (v. 13). For Alma, that word is the seed that we must plant: “And now, my brethren, I desire that ye shall plant this word in your hearts” (33:23). In Alma 33, Alma reveals what that most important seven-part “word” or proclamation is.

| The Word |

|---|

|

Believe in the Son of God, That he will come to redeem his people, And that he shall suffer and die To atone for their sins; And that he shall rise again from the dead, Which shall bring to pass the resurrection, That all men shall stand before him, to be judged (Alma 33:22) |

We give ear to this word when we plant, cultivate, and give room for this word of faith in our lives.

10. Lastly, Alma’s soliloquy ends with a final priestly blessing to all people, grounded in the eternal hope of everlasting life, “that they may sit down in the kingdom of God” and “go no more out” and that all things “may be done according to [the] words” God has promised as Alma has spoken (29:17). Alma’s testimony veritably glows in that bright hope of eternal glory. Let us give ear to that sure word of promise.

In sum, for the many reasons we have discussed, Alma bears a powerful testimony. We do well indeed to give heed to his words. I hope that these few suggestions will help you give closer ear to his words. He speaks directly, boldly, unequivocally, with unflinching language of sure knowledge. As he testifies in Alma 36:4–5 and 26, I would not that ye think “that I know of myself,” for “if I had not been born of God I should not have known these things,” but “many have been born of God, and have tasted as I have tasted,” and the knowledge which I have is of God.” Think of hearing Alma bear this testimony; what a direct and beautiful testimony he bore!

Brothers and sisters, I add my testimony of the truthfulness of the plan of salvation and redemption and of the goodness of the words which Alma has spoken. I say with Alma, “Who can deny” the truthfulness of these words? (5:39). I say with Alma, “Can ye withstand these sayings?” (5:53). I say with Alma, “What have ye to say against this? . . . The word of God must be fulfilled” (5:58), for these things are true.

I hope and pray that in some beneficial way you will never think of the words of Alma quite the same way again, that you will see him as a towering figure in the center of the Book of Mormon out of which so much continues to emerge. His legacy throughout the Book of Mormon is indelible. He did as much as or more than any other to prepare and to hold the Nephite nation together, that there would be a righteous and knowledgeable group preserved to greet the resurrected Lord as he came to instruct them at the temple in Bountiful. I pray that Alma’s words may similarly prepare us to receive the coming of the Savior and to stand before him at the Judgment, which will surely occur one day.

Notes

[1] L. Tom Perry, “Alma the Son of Alma,” in Heroes from the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1995), 98.

[2] Jeffrey R. Holland, “Alma, Son of Alma,” Ensign, March 1977, 79.

[3] Holland, “Alma, Son of Alma,” 84.

[4] S. Kent Brown, “Alma’s Soliloquy: Alma 29,” in Alma, the Testimony of the Word, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 149.

[5] See charts 106–7 at http://

[6] Boyd F. Edwards and W. Farrell Edwards, “Does Chiasmus Appear in the Book of Mormon by Chance?” BYU Studies 43, no. 2 (2004): 103–30.