Review of The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception

R. Devan Jensen

Devan Jensen, "Review of The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception," Religious Educator 16, no.1 (2015): 163–166

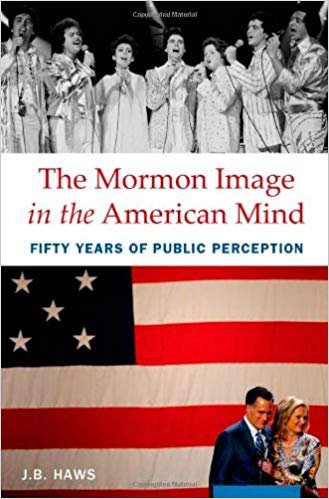

J. B. Haws. The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. Notes, black-and-white illustrations, bibliography, index. 412 pp. ISBN 978-0-19-989764-3, US $29.95.

J. B. Haws. The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. Notes, black-and-white illustrations, bibliography, index. 412 pp. ISBN 978-0-19-989764-3, US $29.95.

This book tells the story of America’s perceptions of Mormonism over the past five decades, bookended by the presidential campaigns of George Romney and Mitt Romney. It deservedly won the Mormon History Association’s Best Book Award for 2013. The book provides valuable historical context to events of modern Church history. In terms of Church publicity, it was truly the best of times, the worst of times.

The introduction notes how little George Romney’s religion affected his presidential campaign of 1968. His credentials were impressive. George led American Motors to new prominence and gave rise to the compact car. His prominent role in company commercials made him a “household name” (1). Elected three times as Michigan governor, he led the state’s constitutional convention. He was also viewed as a progressive in the civil rights movement.

During his campaign, the media viewed his faith neutrally and even positively at times. The New Republic called him “a kind of political Billy Graham.” The Nation commented on his faith as one of his “assets” and a significant part of his “attractive public image” (2). This was a surprising turn from the Church’s image just a few decades earlier when Senator Reed Smoot was grilled in a Senate hearing about his loyalty to the United States because of suspected ties to polygamy.

All seemed golden until a candid but politically damaging comment surfaced about George being “brainwashed” about US involvement in the Vietnam War. His campaign never recovered, but public perceptions of his faith did not contribute to his political downfall.

In contrast to his father’s campaign, Mitt Romney’s credentials were overshadowed by his religion. After years of success at Bain Capital, Mitt helped save the Olympic Games in Salt Lake City. As a Republican, he won the governorship of Massachusetts. But his faith led to serious challenges from the religious right in his first presidential campaign. A Christian website posted the claim that “if you vote for Romney you are voting for Satan” (2). In an NBC News/

The book offers an incredible perspective on swings in public perception toward the Church over the past fifty years. Like the world of politics, public perception is fickle, oscillating drastically as a result of world events and media portrayals. The civil rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s negatively impacted the view of the Church, but some ground was regained after the 1978 revelation extending the priesthood to all worthy men. The title “Church Rites versus Civil Rights” cleverly summarizes the tension between these two worldviews.

In the chapters titled “Familiar Spirits” (parts 1 and 2), Haws discusses the public relations nightmare of anti-Mormon efforts in the 1980s and 1990s. The book and film titled The God Makers had a devastating impact on the Church’s image, with some carryover into the early 2000s. The Mark Hofmann forgeries and bombings similarly left a crater in the Church’s public image. The book offers a noteworthy discussion of six excommunications in September 1993 and the tension growing between conservative and liberal intellectuals of that time. Haws briefly mentions the expulsion of several BYU professors in the 1990s, and this topic could have been explored more. In today’s Church, we still feel the tension simmering between orthodox and progressive views in the Ordain Women and same-sex marriage movements.

In the 1980s to 1990s and on into the 2000s, the pendulum swung to the positive—for example, the national championship BYU football team in 1984, a Mormon Miss America, the Church’s sesquicentennial in 1997, and the 2005 celebration of the bicentennial of Joseph Smith’s birth. President Gordon B. Hinckley’s openness to the media sent a signal of new openness to interviews (158).

In more recent years, popular media portrayed the Church in a more complicated light. The Broadway musical The Book of Mormon surprised audiences with its irreverent but warmhearted tribute to Mormons, and the HBO drama Big Love burned in the public mind an afterimage of polygamy and discouraged some members with its portrayal of sensitive temple scenes.

Surprisingly, faith played a less important factor in Mitt’s second campaign in 2012. Mormon support for Proposition 8 in California did win the ire of same-sex marriage advocates. But media sources mainly portrayed the faith neutrally or positively, and Harry Reid’s presence as Senate majority leader perhaps limited the anti-Mormon rhetoric. Many from the religious right supported Mitt’s second campaign, although they thought of it as, in Larry Sabato’s words, a “shotgun marriage between two very different religions [that] are completely dependent on one another for victory” (265). Chief among those reluctant supporters in 2012 was Pastor Robert Jeffress, who just one year earlier labeled Mormonism a cult. He rejected President Barack Obama’s “perceived attack on religious values and religious liberties” and threw his support to Mitt. Richard Mouw was much more positive about supporting Mormon faith and values.

Haws concludes that public perception of Mormons remains ambivalent. Laurie Maffly-Kipp, professor at the University of North Carolina, wryly summed up deep-seated distrust of Mormons as the invasion of the body snatchers syndrome: “While Mormons embody the economic and moral success endorsed by the American Dream, they also subscribe to beliefs that to many, seem peculiar—even bizarre. . . . No matter how much Mormon behavior conforms to what most consider admirable (and maybe especially because they look so wholesome), some Americans are convinced Mormons secretly await an opportunity to take over the world” (277). This perception will continue as long as Mormons remain in the world but not of the world.

In the concluding chapter, Haws writes that the Church wants to be accepted as Christian, but with a distinctive brand. Terryl Givens stated the paradox this way: “You want to have acceptability . . . [so] that you can fraternize with . . . fellow Christians, but at the same time you don’t want to feel so comfortable that there’s nothing to mark you as a people who are distinct, who have a special body of teachings, a special [body of] responsibilities” (280). This different flair will likely always set us apart from our fellow Christians as well as our fellow Americans.

A limitation of the book is that its well-defined scope circumscribes discussion within the walls of the American political area. There are few references to Church events worldwide or international perspectives of Mormonism. Historians may dislike the placement of notes at the back of the book (rather than footnotes or endnotes).

This book would be excellent for general readers interested in Mormonism’s changing public perception, as well as for teachers of modern Church history seeking context for recent events and the status of the Church in American media and political arenas.