Mission to Missouri

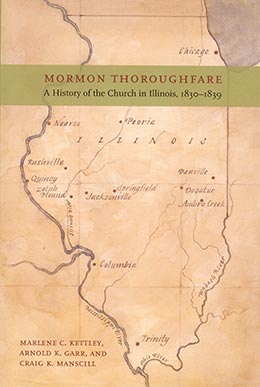

Marlene C. Kettley, Arnold K. Garr, and Craig K. Manscill, “Mission to Missouri, 1831,” in Mormon Thoroughfare: A History of the Church in Illinois, 1830–39 (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2006), 13–30.

Marlene C. Kettley was a researcher and historian, Arnold K. Garr was chair of the Department of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University, and Craig K. Manscill was an associate professor of Church History and Doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

As the “big snow” of the winter of 1830–31 melted in Illinois, missionaries traversed the state preaching the message of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. They had left their families and homes in Kirtland, Ohio, destined for the western borders of the United States—specifically Independence, Missouri. These missionaries, eleven pairs of elders, along with a small group of Church leaders and Colesville Saints, were commanded by revelation to assemble in Missouri for the next conference of the Church (see D&C 52, 54). They were to join Oliver Cowdery, who had been in Missouri for several months. Before leaving New York in October, Cowdery had been told to find the site for “the city Zion” on “the borders by the Lamanites” (D&C 28:9). The Book of Mormon spoke of a holy city in the last days, and many Christians were familiar with the biblical passages about the New Jerusalem coming down from heaven (see Revelation 21:2). The thought that the site of the New Jerusalem was soon to be revealed thrilled Church members. “The most important subject,” said Joseph Smith, “which then engrossed the attention of the saints” was the trip to locate the site of the New Jerusalem. [1] Soon after the members of the Church in New York gathered to Ohio, a revelation was given that commanded them to raise up churches in Ohio until “the time shall come when it shall be revealed unto you from on high, when the city of the New Jerusalem shall be prepared, that ye may be gathered in one” (D&C 42:9).

The call of missionaries to Missouri had a significant impact on the development of the Church in Illinois. The missionaries baptized the first Illinois converts, established the first branches of the Church in the state, and laid the groundwork for the Mormon thoroughfare for those traveling between the two Church centers of Kirtland and Independence.

The Church Leaders’ Party

Joseph Smith and his party of eight travelers left for Missouri on June 19 traveling by “wagon, canal boats, and stages to Cincinnati.” [2] Not wanting to lose time by overland travel, the party journeyed on the waterways skirting around Illinois as far as St. Louis, Missouri. Joseph then reported, “At St. Louis, myself, Brothers Harris, Phelps, Partridge and Coe, went by land on foot to Independence, Jackson county, Missouri, where we arrived about the middle of July, and the rest of the company came by water a few days later.” [3]

When Joseph and his companions reached Independence on July 14, they were greeted by the missionaries to the Lamanites and several new converts. The Prophet expressed his joy at this reunion: “The meeting of our brethren, who had long awaited our arrival, was a glorious one, and moistened with many tears. It seemed good and pleasant for brethren to meet together in unity.” But Joseph’s sentiments of that moment were not without some apprehensions, as he confided, “Our reflections were many, coming as we had from a highly cultivated state of society in the east, and standing now upon the confines or western limits of the United States, and looking into the vast wilderness of those that sat in darkness; how natural it was to observe the degradation, leanness of intellect, ferocity, and jealousy of a people that were nearly a century behind the times.” [4]

Completing a nearly nine-hundred-mile journey, Joseph was taken aback by the primitive conditions of the frontier town of Independence. It had fewer than twenty buildings. It was a bustling trail center for trappers and traders along with a population of southern farmers. No doubt Joseph had expected to find a thriving branch of the Church in Independence, with Oliver Cowdery and Parley P. Pratt proselytizing among their ranks. Joseph’s task of creating a godly civilization in a barbaric wilderness must of have been a foreboding assignment. Yet the resolve to build Zion was imposed forcefully upon the Prophet’s soul.

Not long after their arrival, a revelation confirmed that this was the land of promise, and the place for the city of Zion. “This land, which is the land of Missouri . . . is the land which I have appointed and consecrated for the gathering of the saints” (D&C 57:1). The gathering of Saints to Missouri also included many of the early converts from Illinois, such as William E. McLellin, who followed the missionaries to Missouri and was baptized there by Hyrum Smith.

Over the next few weeks, the Prophet Joseph Smith supervised the dedication of the land and the temple site and presided at the Church Conference. The Independence Saints were to collect funds to buy land and assist in establishing Zion.

After his stay in Missouri, Joseph and those in his traveling party departed on August 9. Their return to Kirtland followed, for the most part, the same route they had previously traveled. [5] Along their way they passed a group of missionaries who had recently crossed Illinois on their way to Missouri. Joseph and his party arrived in Kirtland on August 27.

Colesville Saints

The Saints from Colesville, New York, arrived in Independence on August 2. This party of nearly sixty members skirted around Illinois using wagons and waterways. Unlike the other traveling parties, the members of the Colesville Branch carried all their belongings and provisions. They were the first branch that had immigrated to Zion. The branch settled twelve miles west of Independence on the Kaw River. [6] Newel Knight, their leader, said the task of leading the Colesville Saints “required all the wisdom” he possessed.

Elders Called to Missouri

Eleven pairs of elders were also called to the Missouri mission. These men were among the best the Church had to offer. They included two of the Smith brothers, Samuel and Hyrum. Samuel’s companion was Reynolds Cahoon and Hyrum teamed up with the indomitable John Murdock. Parley and Orson Pratt were two of the most prominent missionaries called to serve, Parley being the eldest. The exuberant Zebedee Coltrin and Levi Hancock, a direct descendent of John Hancock, were called as companions. The other companionships included Lyman Wight and John Corrill; Thomas B. Marsh and Selah J. Griffin; Isaac Morley and Ezra Booth; David Whitmer (one of the Three Witnesses) and Harvey Whitlock; Solomon Hancock and Simeon Carter, from Amherst, Ohio; Edson Fuller and Jacob Scott; and Wheeler Baldwin and William Carter. [7]

All were commanded to “go two by two, . . . preach by the way in every congregation, baptizing by water, and the laying on of the hands by the water’s side” (D&C 52:10). They were further commanded to “take their journey unto one place, in their several courses, and one man shall not build upon another’s foundation, neither journey in another’s track” (D&C 52:33).

Each was promised: “He that is faithful, the same shall be kept and blessed with much fruit” (D&C 52:34). It would be a long, hard journey. The elders would make their way across most of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and then into Missouri. [8]

The missionaries preached to the good people of Illinois while crossing the state after the July Missouri conference. For the most part, the people of Illinois were a cross-section of Christian religions. The people who had settled in southern Illinois, beginning in the 1820s, came mainly from Kentucky and Tennessee. Sydney B. Ahlstrom, in his Religious History of the American People, commented: “The most important single factor in the westward movement of popular piety was the extended ‘Great Awakening’. . . . Because of the revivals (Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist in turn) there were among the migrants a significant number of strongly committed laymen who became missionaries without formal commissioning.” [9] At this time American society was involved in a “century-long process by which the greater part of American evangelical Protestantism became ‘revivalized.’ The organized revival became a major mode of church expansion—in some denominations the major mode.” [10] Such was the religious environment in which the Latter-day Saints missionaries were called to serve.

Almost every pair of elders was ready to leave Kirtland within two weeks of their call. Each set chose a different route because they had been commanded to “not build upon another’s foundation, neither journey in another’s track” (D&C 52:33). Some pairs of elders enjoyed greater success than others. Parley P. Pratt, who had returned from Missouri only a few months before, and his brother Orson spent most of the summer of 1831 preaching in Missouri, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Although they endured a great deal of suffering and hardship, they baptized many people and organized branches in the states they passed through. They did not arrive in western Missouri until September.

Several elders made the journey more quickly. Lyman Wight and John Corrill, for example, completed the trip on foot in two months—from June 14 to August 13. Few of the missionaries, however, arrived in time to participate in the conference held by the Prophet.

Upon arrival in Independence, some of the single elders established themselves as permanent residents, while those with families in the East returned home. With this missionary labor, many people between Kirtland, Ohio, and Independence, Missouri, became acquainted with the Latter-day Saints and their beliefs. Future missionaries would reap where these earliest elders had sown.

The route taken by some of these evangelists is not recorded, making it nearly impossible to determine what part of Illinios they crossed. Journal accounts are scant at best and nonexistent in the cases of Elders Isaac Morley and Ezra Booth.

Of the eleven pairs of elders, two sets did not embark on their mission at all. Edson Fuller and Jacob Scott did not go; neither did Wheeler Baldwin and William Carter. William Carter was willing to go, but his companion was not, and since Carter was blind, the Prophet Joseph asked him to remain in Kirtland.

The following accounts from missionary diaries help to map their travels and report their missionary activities. Since the missionaries had a destination to attain, they usually did not tarry long in any one place.

Lyman Wight and John Corrill

On June 14, 1831, Elders Wight and Corrill commenced their mission with Elders Hyrum Smith and John Murdock from Pontiac, Michigan. Elder John Murdock recorded, “Br Lyman [Wight] and John [Corrill left Detroit and] took the North route through Oakland County [Michigan].” [11] Since neither Wight nor Corrill kept a diary, we must piece together their missionary activities using secondary accounts. Elders Wight and Corrill walked through the sparsely settled forests and broad prairies of northern Indiana and Illinois. A confirmation of their activities is found in the History of Will County: “The Mormons were the first who preached in the settlement [Hickory Creek], and used to promulgate their heavenly revelations as early as 1831.” [12] Maps of this area indicate a rather limited population. Northern Illinois was sparsely crossed by trails of the native inhabitants and by a few wagon roads. While the roads were bogs in wet weather, beds of dust in the dry summer, and frozen ruts in the winter, travelers were still grateful for these roads since they led to a definite destination. One of the most prominent roads in northern Illinois was the Sauk Trail, which eventually became known as the Chicago Road. It served as a military highway and as a prominent stagecoach and mail route between Chicago and Detroit. [13]

Much of northern Illinois was still owned by Native Americans, with the exception of a strip of land referred to as the Indian Boundary, or canal land. In 1821–22, two lines, twenty miles apart and parallel to each other, had been surveyed, beginning at Lake Michigan and crossing parts of the present-day counties of Cook, Will, Kendall, Grundy, and LaSalle, ending at the Illinois River. This land had been purchased by treaty from the Native Americans for building a canal between these two navigable bodies of water. In 1831, pursuant to an act of the legislature, the canal committee laid out the towns of Chicago and Ottawa, each being a terminus of the proposed waterway. The canal became a national project; however, ground was not broken until July 4, 1836, and it would not be completed for years. [14] The treaty land was settled at an earlier date than land outside the boundary. Other lands owned by the Native Americans would not be available until after the Black Hawk War in 1832.

Elders Wight and Corrill traveled along the old Sauk Trail, which passed through the center of Will County in northeastern Illinois. The missionaries would have followed trails or paths branching off to various small settlements or clusters of cabins. They met James Emmett while traveling in the area in July 1831. The 1830 U.S. Census indicates that a James Emmett was living in Will County, Illinois. At the time of the census, the Emmett household had four members: two adults, a male and female between the ages of twenty and thirty years old, and two children under the age of five. There is no record from Emmett himself about his conversion. However, through the autobiography of Morris Phelps and the biography of Charles C. Rich, Emmett’s conversion story is told.

Emmett brought Elders Wight and Corrill to preach at the home of Morris Phelps. Morris and Laura Clark Phelps lived in the northern part of the county, near the Du Page River, in what is now Du Page County. Phelps had previously been introduced to the Church by a relative from Kirtland. The two elders preached before an audience of about twenty, including Phelps, his wife, and several of their neighbors, and then they baptized James Emmett. After carefully examining the records pertaining to the state of Illinois for the year 1831, it appears that James Emmett is likely the first convert in the state. [15] Feeling the joy and gratitude common to converts, Emmett wanted to share his new religion with his friends. According to the History of Will County, one of Emmett’s neighbors, Mr. Buck (a survivor of the “Winter of the Deep Snow”), “turned Mormon, and followed the elect to Nauvoo.” [16]

Leaving northeastern Illinois, Wight and Corrill traveled southwest to Tazewell County. With a letter of introduction from Morris Phelps, they met Sanford Porter, whom they taught for three days. Initially declining baptism, Sanford prayed until he received a spiritual confirmation of the gospel. Porter and several of his family members were baptized on August 10, 1831, likely in the Porter Mill Pond, three miles east of Peoria, Tazewell County (now Peoria County), Illinois. Porter notes in his journal that Jonathan Sumner was also baptized that August. The new converts were ordained elders and both were commissioned to preach the gospel. [17]

In the meantime, Elders Wight and Corrill continued their journey to Missouri. The journals and recollections of other early converts give us an understanding of the diligence of these early missionaries. Hosea Stout and others indicate an early contact with the elders in Illinois and of hearing the message of the Restoration. [18] It is certain the elders would preach as they traveled through the more populated areas of the state. Yet, no direct record of their route or their activities has been found.

John Murdock and Hyrum Smith

Of the elders called to the Missouri mission, Hyrum Smith and John Murdock traveled the furthest. They began their journey traveling northwest towards Detroit, Michigan, then looped south, going through Illinois and Missouri. By the time they arrived in Jackson County, most of the other missionaries had come and gone.

John Murdock recorded that he left Kirtland on June 14, 1831, with Lyman Wight, John Corrill, Mother (Lucy) Smith, her niece, Almira Mack, and Hyrum Smith. They traveled to Detroit on the steamer William Penn. By the sixteenth, Murdock and Smith had traveled as far as Pekin on the Chicago Road (the old military road). On the first of July, they “lodged with Potawatomee Indians.” They received “boiled beans for supper and deerskins to lye [sic] on and pounded venison to eat in the morning.” [19] Murdock gave a fairly detailed account of their journey. He wrote:

[July] 10th Sunday Preached at 11 o clock

Traviled 5 m’s Preached in the evening.

11th Expounded scriptures to a Quaker and preached in evening.

12th 17 m’s to Laffayette Tipacanoe Co. Preached at the courthouse.

[Wednesday] 13th 25 m’s to Atica, and pased where Br’s Carter and S. Hancock baptized some

members 40 m’s s. w. of Loagansport. [20]

As they continued westward, they traveled through “Len Grove,” Sadorus Grove, and then fifteen miles to Pyatt’s Grove. [21] From there it was another fifteen miles to the “old trading house on the Sangamon River,” forty-seven miles southwest of Danville. On July 25, they preached at Decatur, Macon County. Next the elders turned toward Springfield, Sangamon County, preaching two sermons in that area. On August 1, they crossed the Illinois River, and two days later the Mississippi River, entering Missouri. [22]

The next day they reached Salt River, where they remained for seven days. Elder Murdock was ill again, so they hired William Ivie to take them to Chariton, seventy miles away. For the ride, Elder Murdock gave his watch as payment. At Chariton the two missionaries remained a week. During this week, their flagging spirits were revived by a meeting with the Prophet Joseph, Sidney Rigdon, David Whitmer, and Harvey Whitback, who were returning from a visit to the Saints at Independence. While they were all together, they decided that their group should contribute enough money to purchase a pony for Elder Murdock to ride, and this enabled Murdock and Smith to proceed on their way. The ailing Elder Murdock rode the pony fifty miles to Lexington, located on the Missouri River. At Lexington, Smith and Murdock slept in an unfinished building where only half the floor was laid. During the night, Elder Murdock, suffering from a high fever, attempted to get to an open window on the opposite side of the room. In doing so he stepped off the floor and fell across the uncovered joints. Hyrum, hearing the crash and the groans that followed, sprang from his bed and assisted his companion back to the floor and into bed. [23]

Despite their trials as they pressed westward, Hyrum and his companion followed the command of the Lord to preach the gospel at every opportunity. In the villages, towns, cities, and frontier homes, they found a heterogeneous people: some righteous, some believers, some cultured, and some opposite to all of these. The missionaries often were depressed in spirits over the conditions of wickedness, ignorance, and priestcraft they met on all sides. However, they continued to sow their seed and found that some fell on fertile soil. There were people who listened, investigated, and received a conviction of the truth. When at last they reached Independence, Missouri, these two seasoned missionaries met the Saints who had preceded them with a great feeling of rejoicing and tears of joy.

After staying in Missouri for a short time, William McLellin and Hyrum Smith returned to Ohio. On September 7 they reentered Illinois at Atlas. On the ninth they arrived at Jacksonville, Morgan County. The next day, Saturday, they preached at the court house with about five hundred in attendance. McLellin noted there was “perfect silence and good attention.” They continued eastward, visiting McLellin’s brother Israel and uncle William Moore. On the seventeenth they reached Shelbyville, where they preached. On Sunday they preached at a location seven miles to the northeast. By September 20 they had arrived at Charleston, Cole County, where McLellin had business to conduct. The next day they preached and wrote “people seemed quite believing.” On the twenty-second they visited the grave of McLellin’s wife, and on the twenty-third they had an appointment to preach in the schoolhouse by “candle light.” This meeting was held in the same building where McLellin had previously taught. They preached again on Sunday at the Hicklins’ home, where some of their listeners were angry and others were inquiring. The twenty-ninth found Smith and McLellin leaving Illinois, continuing their journey to Kirtland. [24]

Thomas B. Marsh and Selah Griffin

Originally Elder Marsh was assigned Ezra Thayer as his companion, but Ezra, who failed to prepare himself to serve, was replaced by Selah Griffin, who had previously been assigned to Newel Knight. Elder Knight had been called to lead the Colesville Branch to Missouri.

Little has been recorded of the missionary efforts of these elders. Thomas Marsh and Selah Griffin traveled to Missouri, “preaching by the way.” [25] These two diligent missionaries left Kirtland about the middle of June 1831. They commenced to preach in the various townships through which they passed on their way to Missouri; apparently they met with several sincere investigators in this endeavor, for they recorded that “many believed our testimony, but we did not wait to baptize any.” [26]

Reynolds Cahoon, who had reached Missouri and was returning home by way of Boone County, Missouri, met up with Griffin and Marsh. Elder Cahoon wrote that “Brother Marsh was sick so we prayed with him and layed [sic] hands upon him. We remained with him that night and preached in the evening. The next day we obtained some physic [medicine] and gave to Bro. Marsh, after which we continued our journey.” [27]

Marsh was not alone in his affliction; both John Murdock and Parley P. Pratt were likewise discomforted during this same mission. While recovering, Marsh stayed at the home of Benjamin Slade in Missouri. He probably arrived in Independence in August or September 1831, where Bishop Partridge provided him with a pony for his return to Kirtland, accompanied by Cyrus Daniels. [28]

Isaac Morley and Ezra Booth

There is no apparent record of the missionary travels of Isaac Morley or Ezra Booth. We do know, however, that while they were on the mission Ezra lost his faith in the prophetic calling of Joseph Smith. President Joseph Fielding Smith explained, “Through the performance of a miracle he was baptized, and from that time he desired to make men believe by the performance of miracles, even by smiting them, or with forcible means.” [29] When Ezra returned to Ohio in September 1831, he was an apostate. Fellowship was withdrawn from him on September 6, 1831. At the time Joseph Smith received a revelation that said, “I, the Lord, was angry with him who was my servant Ezra Booth, . . . for [he] kept not the law, neither the commandment” (D&C 64:15). “Ezra officially denounced Mormonism on 12 September 1831 and published a series of nine letters in the Ohio Star, a paper printed in Ravenna, Ohio, explaining the ‘Mormon delusion.’” [30]

David Whitmer and Harvey Whitlock

Unfortunately, neither David Whitmer nor Harvey Whitlock left an account of their missionary activities. The best account of their mission comes through the journal and letters of William E. McLellin. One such letter was written by McLellin to his non-Mormon relatives, warmly and carefully recounting his conversion the year before, which began when two different sets of the elders, traveling to Zion in 1831, preached in his village of Paris, Illinois. The first pair, Samuel Smith and Reynolds Cahoon, held an evening meeting and described in detail the coming forth and contents of the Book of Mormon. They left the next morning. McLellin’s next exposure to the new religion is recounted in this letter:

But in a few days two others came into the neighborhood proclaiming that these were the last days, and that God had sent forth the Book of Mormon to show the times of the fulfillment of the ancient prophecies, when the Savior shall come to destroy iniquity off the face of the earth and reign with his saints in Millennial Rest. One of these was a witness to the book and had seen an angel, which declared its truth. His name was David Whitmer. They were in the neighborhood about a week. I talked much with them by way of enquiry and argument. They believed Joseph Smith to be an inspired prophet. They told me that he and between 20 & thirty [of] their preachers were on their way to Independence. My curiosity was roused up and my anxiety also to know the truth. [31]

McLellin wrote that Elders David Whitmer and Harvey Whitlock preached and bore their testimonies of the restored Church a few days after Smith and Cahoon. [32] McLellin states that he arranged for these elders to preach at Paris to a large assembly. Perhaps Thomas Rhoades was one of those who first heard the gospel while residing in the area of Paris, Edgar County. [33] On July 30, McLellin closed the school where he was teaching and followed the missionaries to Missouri. He traveled with the elders through Shelby County, but parted from them to visit his brother and uncle at Springfield. McLellin then continued on to Independence, where he was soon baptized by Hyrum Smith.

Parley Pratt and Orson Pratt

Courtesy of Church Archives

Courtesy of Church Archives

The Pratt brothers also give few details of their missionary labors. Parley’s autobiography states: “After the conference my brother and myself commenced our journey . . . [and] traveled through the States of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Missouri, in midst of the heat of summer on foot, and faithfully preached the gospel in many parts of all these States.” Parley and Orson were successful, as they “baptized many people and organized branches of the Church in several parts of Ohio, Illinois and Indiana.” [34] However, their journey was exhausting. When they reached upper Missouri, “they collapsed in the summer heat; first Orson, then Parley, fell ill with fever and chills. . . . The two finally arrived at Jackson County after a thousand miles and at least fifty wayside meetings.” [35] The names of converts and locations of branches are missing from these accounts. Likely the new members soon traveled to Missouri, as did many of the newly baptized in northern Illinois. Orson notes that he returned to Ohio in the company of Brother Dobbs, even though Orson was suffering from the ague. [36]

Parley remained in Missouri for the winter of 1831–32. In 1832, John Murdock returned east with Parley Pratt, having preached in various places in Missouri. On March 8 they crossed the Mississippi River for the last time, being unable to secure a place to preach in St. Louis. On the ninth, they traveled to Eportis and preached that evening. Elders Murdock and Pratt preached in the Baptist meetinghouse at Canteen [Madison County] again in Illinois. For the next several days, they would preach daily. On the thirteenth they were awakened at midnight by Isaac K. McMahan, who had followed them for twenty-seven miles in order to be baptized. McMahan insisted on being baptized immediately, so the services were held at two o’clock in the morning. McMahan was then ordained an elder and taught the importance of gathering to Zion.

Pratt and Murdock then preached in Greenville (Bond County) and baptized Joseph Young. They continued to teach as they traveled across Illinois. On the seventeenth they preached at Vandalia, Fayette County, the state capital. By March 18 they were about five miles from any house when Parley began to shake from ague. [37] Murdock then administered a blessing to Pratt, whereupon he fully recovered.

It is sometimes difficult to appreciate the challenges these early missionaries faced. Though Brother Parley felt he had “little faith,” he did not lack courage and determination to complete the assignment given to him by Church leaders. These elders preached thirty-one times between there and Orange, Ohio. [38] Their route seems to be fairly close to that of the “National Road,” which extended from Baltimore, Maryland, to St. Louis, Missouri.

Solomon Hancock and Simeon Carter

Solomon Hancock and Simeon Carter established a branch in the area of Attica, Indiana. [39] Hancock and Carter had arrived on July 4, preached in the area for four or five days, and baptized about thirty people. Three or four weeks after these elders left, Thomas B. Marsh and Selah Griffin came into the area as they returned from Missouri on their way to Kirtland in the fall. [40]

Reynolds Cahoon and Samuel Smith

Samuel H. Smith and Reynolds Cahoon left Kirtland on June 9. After traveling through Ohio and Indiana, they crossed into Illinois near Terre Haute, Indiana. At Paris, the seat of Edgar County, they preached in the courthouse. Lucy Mack Smith’s historical account of her son Joseph Smith tells what happened in Paris, Illinois:

Samuel replied that he would be glad of the opportunity. Mr. McLellin went out, and in a short time he had a large congregation seated in a convenient room, well lit up at his expense. After the meeting was dismissed, Mr. McLellin urged them to stay in the place and preach again, but they refused, as their directions were to go forward without any further delay than to warn the people as they passed.

Soon after they left, which was the next morning, Mr. McLellin grew uneasy, and he afterwards told me the following story:

“When night came I was unable to sleep, for I thought that I ought to have gone with them, as I had an excellent horse, and I could have assisted them much on their journey. This worked upon my mind, so that I determined to set out after them the next morning, cost what it might. I accordingly told my employer what I had concluded to do, and obtaining his consent, I set out in pursuit of my new acquaintances. I did not overtake them, but I pursued my route in the same direction, until I came to Jackson County, Missouri, where I was baptized.”

On their route, Samuel and Brother Cahoon suffered great privations, such as want of rest and food. On this journey, they passed through Quincy. There were only thirty-two houses then in the place, and they preached the first sermon [of Mormonism] that ever was delivered in that town. [41]

The elders found the local residents uninterested. They traveled fifty-five miles before holding another meeting. On July 17, they met with a Presbyterian congregation. As Smith and Cahoon continued westward, they passed through Springfield and later crossed the Illinois River. There is record of their preaching at Rushville, Schuyler County on Friday, July 22. On Sunday they preached at the home of a Mr. Orr. Shortly they reached the Mississippi River and crossed into Missouri.

Other elders traveled through Illinois as they returned to their homes in Ohio. Samuel Smith and Reynolds Cahoon reentered Illinois on August 20 near Alton, Madison County. They passed through Edwardsville, Madison County, and reached Vandalia, Fayette County, on Wednesday, August 24. From there it appears that they traveled on the National Road to Terre Haute, Indiana.

The 1831 mission to Missouri had a significant impact on the establishment of the Church in Illinois. The message of the Restoration of the gospel was spread across the state within five months. At great sacrifice, these missionaries answered the call to serve. They baptized many people of whom some gathered to Zion, in Jackson County, Missouri, to strengthen the Church. They established branches of the Church and set apart others to preach and lead after their departure. These branches became important way stations or stopovers for future missionaries, Zion’s Camp, and the refugees of Kirtland Camp. In this way the Missouri mission established a thoroughfare between the two centers of the Church—Kirtland, Ohio, and Independence, Missouri. Illinois had found its place in Church history.

Notes

[1] See Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2nd ed. rev., ed. B. H. Roberts (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 1:188.

[2] The travelers included “Sidney Rigdon, Martin Harris, Edward Partridge, William W. Phelps, Joseph Coe, Algermon S. Gilbert and his wife” (Smith, History of the Church, 1:188).

[3] Smith, History of the Church, 1:189.

[4] Smith, History of the Church, 1:188.

[5] Smith, History of the Church, 1:206.

[6] Andrew Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1941), 874.

[7] Samuel H. Smith (1801–44), a vative of Tunbridge, Vermont, was a younger brother of Joseph Smith. He was one of the Eight Witnesses. He is traditionally recognized as the first missionary of the Church. He served as a member of the Kirtland high council. He participated in the battle of Crooked River in 1838. He died in Nauvoo in 1844 (see Far West Record, ed. Donald Q. Cannon and Lyndon B. Cook [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983], 289.)

Hyrum Smith (1800–44), born in Tunbridge, Vermont, was the elder brother of Joseph Smith. He was one of the Eight Witnesses. He became the assistant counselor in the First Presidency in 1837 and then Second Counselor to Joseph Smith later that same year. He was called to the office of patriarch in 1841. He was killed with the Prophet in 1844 (see Far West Record, 288).

Reynolds Cahoon (1790–1861), a native of Cambridge, New York, was baptized in 1830 and ordained a high priest in 1831. He was a counselor to Bishop Whitney in Kirtland and a member of the stake presidency in Adam-ondi-Ahman and in Iowa. He died in Salt Lake City, Utah (see Far West Record, 252).

John Murdock (1792–1871) was born in Kortwright, New York, was baptized in 1830 and ordained a high priest in 1831. He was a counselor to Bishop Whitney in Kirtland and a member of the stake presidency in Adam-ondi-ahman and in Iowa. He died in Beaver, Utah (see Far West Record, 278).

Orson Pratt (1811–81) was born in Hartford, New York, and joined the Church in 1831. He was a member of Zion’s Camp and of the high council in Clay County, Missouri in 1834. He was ordained an Apostle in 1835. He was excommunicated in 1842 but was rebaptized in 1843 and returned to his apostleship. He dies in Salt Lake City (See Far West Record, 283).

Parley P. Pratt (1807–57), brother or Orson and a native of Burlington, New York, was baptized and ordained an elder in September 1830. He was ordained a high priest the next year. He was one of the great early missionaries of the Church, his missions including the Lamanite mission to Missouri in 1830–31. He became an Apostle in 1835. He was assassinated in 1857 while on a mission in Arkansas (see Far West Record, 283).

Zebedee Coltrin (also Zebidee Coultrin) (1804–87) was a member of Zion’s Camp and was afterward ordained a member of the First Quorum of the Seventy. He also served as a member of the stake presidency in Kirtland. He settled in Spanish Fork, Utah (see Far West Record, 256).

Levi W. Hancock (1803–82) was baptized by Parley P. Pratt in November 1830. He was a member of Zion’s Camp and was afterward a President of the First Quorum of the Seventy. He also marched with the Mormon Battalion. He died in Washington, Utah (see Far West Record, 256–66).

Lyman Wight (1796–1858), a native of Fairfield, New York, was baptized in November 1830 and was ordained a high priest in 1831. He became an Apostle in 1841 after having served as a military leader and valiant defender throughout the Missouri difficulties. After the Prophet’s death, he led a group that settled in Texas. He was eventually cut off from the Church (Far West Record, 295).

John Corrill (1794–?), a native of Massachusetts, was baptized in 1831 and ordained a high priest and assistant to Bishop Partridge. He was a prominent leader in Jackson County, but he was excommunicated in 1839 in Far West when he joined with other dissenters (see Far West Record, 256).

Thomas B. Marsh (1800–66) was born in Acton, Massachusetts, and joined the Church in September 1830. He was appointed physician to the Church. He moved to Missouri and became a member of the high council in Clay County. In 1835 he was ordained an Apostle. In 1838 he became one of the “dissidents” who disagreed with Church leadership. He was excommunicated but was rebaptized in 1857 (see Far West Record, 276).

Selah J. Griffin (1792–?) was called on a mission with Thomas B. March in 1831. He lived in Jackson County, Missouri, and later in Caldwell County. He was a blacksmith (see Far West Record, 265).

Isaac Morley (1786–1865), a native of Montague, Massachusetts, was baptized in November 1830 and was ordained a high priest in 1831. He suffered with other Church leaders through the persecutions in Jackson County, Missouri, in 1833. He was a patriarch in Far West, Missouri, in 1837. He played important roles in Nauvoo and in Utah (See Far West Record, 277).

Ezra Booth (1792–?) was a Methodist preacher joining the Church. He was ordained a high priest in 1831 but was excommunicated later that year. He subsequently wrote nine anti-Mormon letters that appeared in the Ohio Star, thus becoming the first Mormon apostate to publish anti-Mormon literature (see Far West Record, 249).

David Whitmer (1805–88), a native of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, was one of the first members of the Church and one of the Three Witnesses. In 1834 he was ordained President of the Church in Missouri and successor to Joseph Smith. However, in 1838 he apostatized from the Church and was excommunicated (see Far West Record, 294).

Harvey Whitlock (1809–), a native of Massachusetts, was ordained a high priest in 1831. He located in Missouri that year. He was disfellowshipped about 1834 and excommunicated in 1838 (see Far West Record, 294).

Solomon Hancock (1793–1847), a native of Springfield, Massachusetts, was baptized in 1830 and was called on a mission to Missouri in 1831. He moved with his family to Jackson County in 1832. He was later a member of the high council in Clay County (see Far West Record, 266).

Simeon Dagget Carter (1794–1869), a native of Killingworth, Connecticut, was ordained a high priest in 1831 and was a member of the high council in Clay County and in Far West, Missouri. He served a mission to Germany in 1841. He died in Brigham City, Utah (see Far West Record, 253).

Edson Fuller (1809–?) was baptized and ordained an elder before June 3, 1831. He was soon after sent on a mission to Missouri but was troubled by evil spirits and excommunicated later that same year (see Far West Record, 261).

Wheeler Baldwin (1793–1887) was ordained an elder in 1831 in Ohio and a high priest later that same year. He joined with the Reorganized Church in 1863 (see Far West Record, 247).

William Carter (1798–1884) lost his elder’s license in September 1831 (see Far West Record, 253).

[8] The areas in which the Elders traveled, if known, in Illinois were:

Lyman Wight and John Corrill (north and central)

John Murdock and Hyrum Smith (central)

David Whitmer and Harvey Whitlock (central)

Parley P. Pratt and Orson Pratt (central)

Reynolds Cahoon and Samuel Smith (central)

[9] Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972), 431.

[10] Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People, 435.

[11] John Murdock Journal, Church Archives, MS 1194 2–3, June 14, 1834.

[12] The History of Will County (Chicago: William Le Baren Jr., 1878), 503. Hickory Creek Settlement referred to an area which included Joliet, New Lenox, Frankfort, and Homer. In March of 1831, the newly organized Cook County included parts of what is now Will County, all of Du Page, Cook, and Lake counties. It was organized into three districts: Chicago, Hickory Creek, and Du Page.

[13] Muriel Mueller Milne, Our Roots Are Deep: A History of Monee, Illinois (South Holland, IL: South Suburban Genealogical and Historical Society, 1990), 86. They were likely following “the old Sauk Trail,” which had been surveyed between Chicago and Detroit in 1821, and named the “Chicago Road.” It was a military highway.

[14] Augustus Maue, The History of Will County, Illinois (Topeka: Historical Publishing Company, 1928), 2 vols., 428; Past & Present of LaSalle County (Chicago: H. F. Kett, 1877), 162; “Walking east on Main Street to the bridge offers a view of where early Ottawa’s cabins clustered near the mouth of the Fox River.”

[15] US 1830 census, Putnam County, 302 (which included the present Cook, Du Page, Kane,) Kendall, Grundy, Will, LaSalle counties or roughly the upper northeastern part of Illinois, lists James Emmett as living in the general area of the present Plainfield-Bollingbrook area. James was born in 1803 in Kentucky and in 1823 married Phoebe Jane Simpson. They were parents of ten children. After his baptism in 1831, he joined the Saints in Independence, Missouri. With many other Saints, he filed a claim against the state of Missouri. James served as a missionary, first with Peter Dustin and then with Ira Ames. This family joined the Saints at Nauvoo. There his son James was struck by lightning and died age eight. James is an interesting study. When committed to the gospel, he was faithful and willing to do all he could to further the cause but was later disfellowshipped for leading a group of Saints away from Nauvoo. They went with the Saints to Utah. He died in California (see Clark V. Johnson, Mormon Redress Petitions, Documents of the 1833–1838 Missouri Conflict (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1992); Smith, History of the Church, 5:513; 7, 270, 434).

[16] Maue, The History of Will County, fn 312. Additional information about “Mr. Buck” has not been located, though local and Church histories have been checked.

[17] Sanford was born in 1790 in Massachusetts, son of Nathan and Susannah (West) Porter. In 1812 he married Nancy Warriner. She was born in Vermont, the daughter of Reuben and Sarah (Colton) Warriner. Sanford and Nancy were parents of thirteen children, the first six born in New York, the next four in Ohio. This family came to Illinois in 1828, having traveled with Timothy B. Clark and family. Three children were born while they lived in Illinois, the last was born in Missouri. His wife, eldest son, and daughter were baptized with him. Sanford was faithful to the gospel all of his life. He led a group of Saints from Illinois to Missouri in 1831, leaving their home in December and reaching Independence in March. There are records of his faithful service to the Church. His journal provides insight into his character. At age seventy-three, he broke his leg chopping wood. It was thirty-six hours before a doctor could treat him. Sanford wrote: “By then the leg had turned a bad color. The Doctor said the leg would have to come off. [I] replied, when I go, I will go all together . . . The Doctor set the leg as best as he could. [Sanford asked the doctor and his sons to administer to him] and if the Lord was willing, I would live and the leg heal, . . . but my time was not yet, my leg healed all right.” Later he wrote: “My greatest trial came in 1864, my lifes pardner was taken from me and a deer good wife and mother she had always been. Then life lost its interest, but we must all remain until our time had come” (Sanford Porter, Reminiscences, Church Archives, 40).

[18] Hosea Stout, born in 1810, the son of Joseph and Anna Stout. In about 1819, the family moved to Ohio. His mother died in 1824. After this he and his cousin Stephen moved to Tazwell County, Illinois, and joined the household of Ephriam Stout at Stout’s Grove in Danvers Township, McLean County. In 1830 Hosea was an employee of Morris Phelps, while Phelps was living at Willow Springs, now Dillon, Illinois. He later taught school at Ox Box Prairie in 1832 and served in the Black Hawk War. Allen Stout wrote: “In spite of Hosea’s conversion, but lacking courage to be baptized, he returned to Stout’s Grove and commenced preaching the doctrine [of the Latter-day Saints], to his many astonished relatives. Two years later, Hosea was still hesitating when Hyrum Smith and Lyman Wight passed through Stout’s grove on their way to join the main body of Zion’s Camp” (Wayne Stout, Hosea Stout: Utah’s Pioneer Statesman [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1953], 32–33).

[19] John Murdock Journal, Church Archives, July 1.

[20] John Murdock Journal, Church Archives, July 9.

[21] James N. Adams and William E. Keller, Illinois Place Names (Springfield, IL: Illinois State Historical Society, 1968), 420. “Len Grove” is Linn Grove and Sadorus Grove, now Sadorus; both located in Champaign County. Pyatts, now called Monticello, is located in Piatt County.

[22] John Murdock Journal, Church Archives, August 1. William McLellin recorded being at Atlas, Pike County, Illinois, and then crossing the Mississippi River. There he learned that Hyrum Smith and John Murdock had been there only one week before (see William McLellin Journal, Church Archives).

[23] John Murdock Journal, Church Archives, 6.

[24] William McLellin Journal, Church Archives, 1.

[25] Millennial Star, June 11, 1864, 376.

[26] Millennial Star, June 11, 1864, 376.

[27] Journal History of the Church, August 13, 1831.

[28] Walter C. Lichfield, Thomas B. Marsh, Physician to the Church (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1956), 32.

[29] Joseph Fielding Smith, Essentials in Church History (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1973), 116.

[30] Susan Easton Black, Who’s Who in the Doctrine and Covenants (Salt Lake City, 1997), 31.

[31] Wm. E. and Emiline McLelin to Samuel McLelin, Independence [Missouri], August 4, 1832. The surname follows William’s later spelling in the article. We have edited certain capitalization and punctuation in this extract retaining McLellin’s underlining. Letter copied courtesy of RLDS historian Richard P. Howard.

[32] Andrew Jenson, Biographical Encyclopedia of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jensen History Company, 1901) 1:280.

[33] Kate B. Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1972), 371.

[34] Parley P. Pratt, Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1972), 68–69.

[35] Breck England, The Life and Thought of Orson Pratt (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1985), 28.

[36] Breck England, The Life and Thought of Orson Pratt (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1985), 28–29.

[37] John Murdock Journal, Church Archives, March 9.

[38] John Murdock Journal, Church Archives, March 15.

[39] Attica, Fountain County, Indiana, is northeast of Danville, Illinois.

[40] Kate Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage, 12:222. John Loveless recorded being baptized by Solomon Hancock and being confirmed by Simeon Carter, at or near Attica. In October, Carter returned “from his tour to Zion in Jackson County, Missouri.” Two weeks later, Solomon Hancock returned and baptized Mahala, John’s wife. John reported the Church was compelled to leave by a mob about November 1, 1831.

[41] The Revised and Enhanced History of Joseph Smith By His Mother, ed. Scot Facer Proctor and Maurine Facer Proctor (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1998), 280.