Richard O. Cowan: Fifty-Three Years as a Teacher, Scholar, and Mentor

Lloyd D. Newell

Lloyd D. Newell, “Richard O. Cowan: Fifty-Three Years as a Teacher, Scholar, and Mentor,” in An Eye of Faith: Essays in Honor of Richard O. Cowan, ed. Kenneth L. Alford and Richard E. Bennett (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, 2015), 1–30

Lloyd D. Newell was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was published.

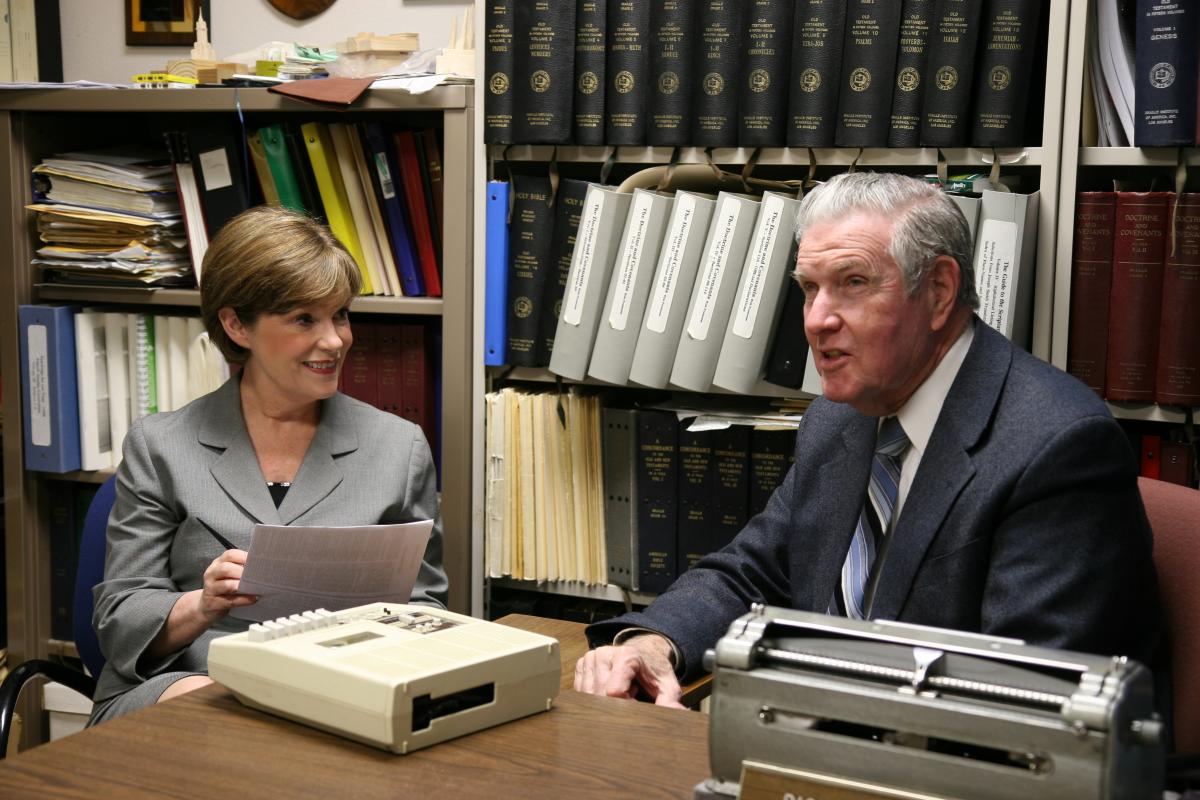

Richard and Dawn Cowan. (Courtesy of Dawn H. Cowan.)

Richard and Dawn Cowan. (Courtesy of Dawn H. Cowan.)

Anyone who has known or interacted with Richard O. Cowan knows that he is a most unusual man. It does not take more than a few moments with him to feel of his uncommon goodness, his unfailing kindness, and his wisdom and perspective. Being unable to see well with his physical eyes for most of his life has not stopped him from seeing clearly with his spiritual eyes the power and truth of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the world and its remarkable beauty, and all that is good and ennobling in others. I have long been impressed with his extraordinary vision.

For example, in 2000 I was asked by BYU Religious Education to arrange a tour of the newly constructed Conference Center on Temple Square. A few years later I was also asked to organize a tour of the newly renovated Tabernacle. On both occasions, the first to inquire about and sign up for the tour was Richard Cowan. He was also the most excited about it. I found out later that both tours were requested because of his enthusiastic encouragement. He came on both tours with his beloved wife, Dawn, and together, arm in arm, they listened intently, deeply breathed in the air of both buildings, and seemed to want to soak in every moment. I have never forgotten it. He wanted to be “on location” and “see” it with his own eyes. Others will tell you that he is the same way on Church history tours, in-service trips, and speaking assignments around the world.

You sometimes have to remind yourself that he can’t see with his eyes, because he sees very clearly those things that matter most. And those things are the things he has in abundance: love and light, goodness and generosity, humility and meekness, compassion and kindness, to name only a few. He is a loving man with a loving wife and family. He is a man of God who loves the Lord and the gospel. He is a scholar who has authored or edited more than a dozen books and written scores of articles for Church and scholarly publications. He is a teacher who has informed and inspired more than forty thousand students.

Richard was born in Los Angeles, California, on January 24, 1934. His parents, Lee R. and Edith Olsen Cowan, taught him the gospel and believed in his talent and capacity to become whatever he put his mind to. His only sibling, a dear sister, Jean Simpson, said of him:

What I remember most about Richard growing up was his great thirst to learn about everything! He always had a questioning mind. Topics ranged from the solar system to trains, airplanes, and boats to the early California Missions and everything in between. Our mother did everything possible to nurture those interests, with the desire that Richard would have as normal a life as a sighted person. I remember outings to Griffith Park Observatory to learn more about the planets, trips to the ship yards in San Pedro (including a launching) to tour ships, sitting under the flight path at LAX to watch and hear the planes go over, trips to Union Station to get up close to the trains, visits to just about all of the Catholic Missions. Richard had a set of Young Science books about a myriad of topics, which all became ragged from use. Mother would read to him incessantly.

He was always very tactile; he would like to feel things with his hands to better understand the composition—to “visualize” it. He built scale models of many airplanes, ships, and the Missions. Not just from kits, but with balsa wood, sandpaper, an X-Acto knife, glue, and paint. He would have the details perfect on these models. Don’t ask me how he did it! It was always obvious that Richard had a brilliant mind and was very successful academically. Though he went to special schools through high school, he took part in student government in high school.

Richard’s love for learning led him to enroll at Occidental College in Los Angeles, where he rode the bus and streetcar most days to get to and from campus. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa at Occidental before going on to Stanford University for his master’s and PhD degrees. Jean remembers his incredible memory as she read university textbooks to him: “I would be reading a text to him, and he might say, ‘Go back a page, down to a paragraph that started . . . and read that again, please.’ Once he heard it, he remembered it.”

Commenting on the two sides of her brother’s nature, she said: “Richard was blessed with a great sense of humor and likes to laugh and crack jokes (usually very corny ones). He also has a serious and spiritual side. He took great pleasure in temple trips we would take to do baptisms for the dead. When the Los Angeles California Temple was being built, he wanted to keep up on the progress by visiting the site, and even asked to come home from his mission a little early so he wouldn’t miss the dedication.” (As it turned out, he completed his full mission and was able to attend the dedication a few days later).

Of Richard’s mission, Jean said, “Who would have thought that a visually handicapped young man would be able to learn Spanish and go to Texas and New Mexico for two-and-a-half years! But he did and was a very successful missionary. I think he made a commitment early in his life to serve the Lord whenever possible, having the faith that he would be blessed in return. And he has been right.”

Richard served the Lord in the Spanish-American Mission from 1953 to 1956. In 1958 he married his beloved wife, Dawn Houghton of Berkeley, California, in the Los Angeles California Temple. Three years later he finished his PhD at Stanford University, and he and Dawn moved to Provo, where he would teach at Brigham Young University for the next fifty-three years. His longevity in Religious Education, together with his scholarly contributions, will not soon be surpassed.

While at BYU he served as a counselor in a campus stake presidency, chaired the Gospel Doctrine Writing Committee for the Church for nearly twenty years, chaired the Department of Church History and Doctrine in Religious Education for three years, and in 2008 was ordained stake patriarch in the Provo East Stake. He retired from full-time faculty in Religious Education in April 2014.

Any who have been blessed to associate with Richard and Dawn Cowan over the years feel inspired, grateful, and humbled to consider them colleagues and friends. They are exceptional examples of synergy at work: together they are greater than the sum of their parts. Truly they are remarkable individuals who compose an even more remarkable team.

Blindness has never inhibited Richard. Dana Pike is shown catching Richard at the end of a several-hundred-yard zip line. (Courtesy of BYU Religious Education.)

Blindness has never inhibited Richard. Dana Pike is shown catching Richard at the end of a several-hundred-yard zip line. (Courtesy of BYU Religious Education.)

The following is excerpted from a series of discussions that took place between Lloyd Newell and Richard Cowan during summer 2014 shortly after Richard’s retirement from Brigham Young University.

Newell: Sometimes when I am with you I have to remind myself that you are unable to see. You are so interested in “seeing” everything around you. I think you have remarkable vision in the sense that you can see the best in others and see the beauty around you. Tell us about your eyesight.

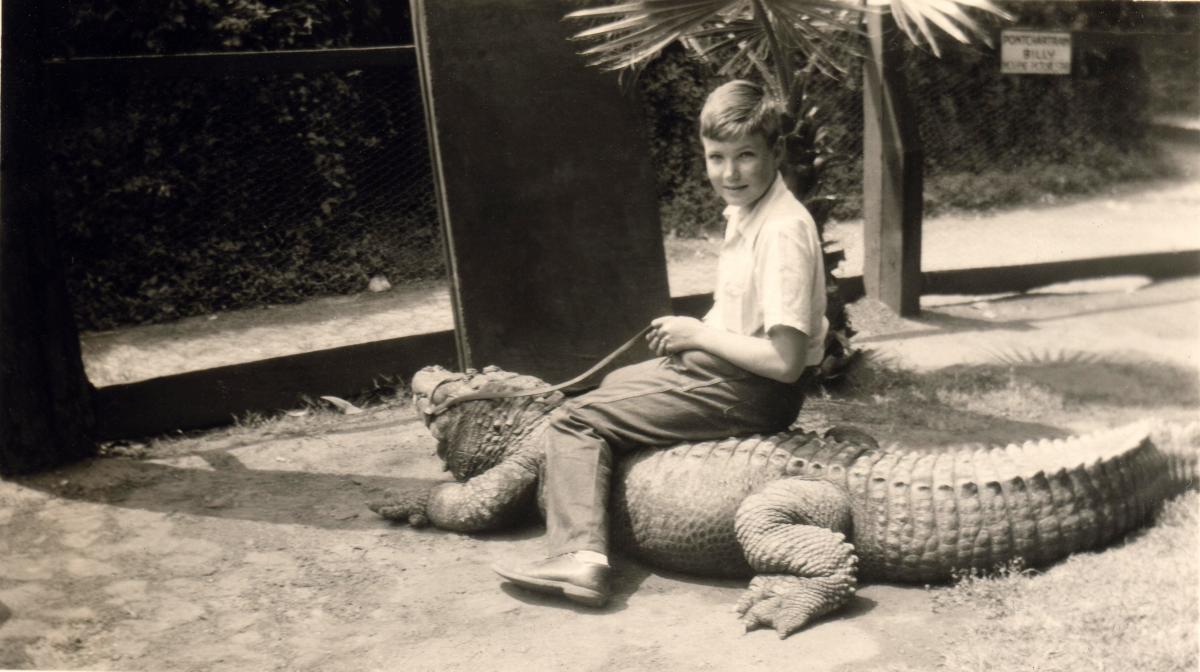

Richard at the alligator farm in Los Angeles. (Courtesy of Richard O. Cowan.)

Richard at the alligator farm in Los Angeles. (Courtesy of Richard O. Cowan.)

Cowan: I was born with poor eyesight, but I could see more than I do now. It was a condition that the doctor said would be deteriorating over the years. About ten years ago I got to the point where I had no vision left at all. Of course, I’m talking about physical vision.

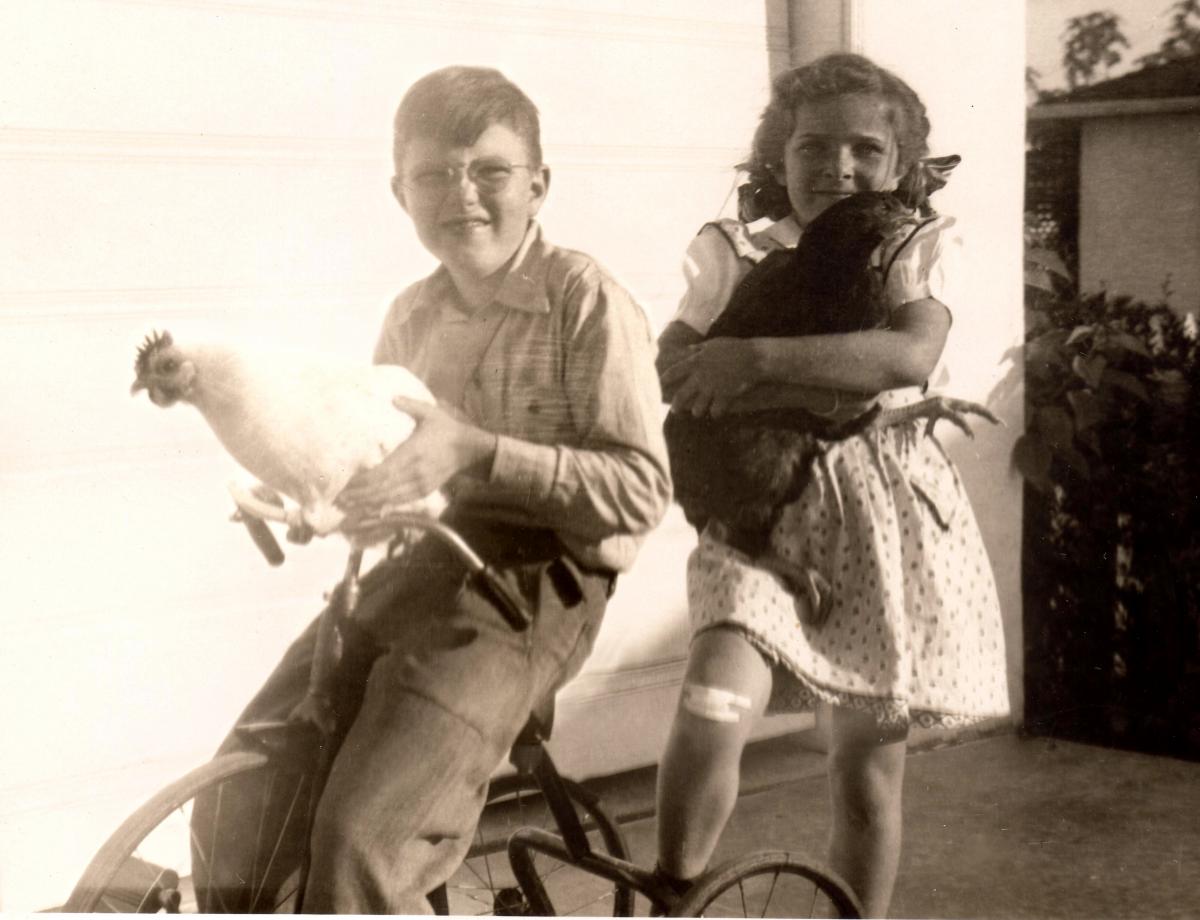

My parents were wonderful helps during my growing-up years. My mother particularly wanted to make certain that I didn’t miss out on anything just because I couldn’t see well. For example, I have a picture from my childhood that shows me sitting on a real live alligator at the alligator farm in Los Angeles. Mother took me to airports, the harbor, the observatory, and all sorts of different places to see things. I also had hobbies; I liked science and making models of ships and planes. I have another photo of my sister and me with our pet chickens on our tricycle handlebars. The point is that our mother enabled me to have a broad experience.

I started school in a special program called Sight Saving. In Los Angeles this program was available only at certain schools assigned to offer these special programs, so I couldn’t go to our neighborhood schools. When I was in junior high, I was able to ride the normal transit bus and streetcars, needing to transfer twice to get to and from school each day. Sight Saving had us read from books with large print, hoping that maybe we could be accommodated that way. However, by the time I was ready to go to high school, it was apparent that my vision was not good enough to stay in that program, so I was assigned to learn Braille. The thing that really hurt me was that I had to ride the school bus; I wasn’t able to be independent and get there on my own. I resented that sort of a comedown. I also did not like Braille. I thought of a blind person as the guy with a tin cup on the street corner asking for alms, and I did not want any part of that.

Richard, sister Jean, and pet chickens. (Courtesy of Richard O. Cowan.)

Richard, sister Jean, and pet chickens. (Courtesy of Richard O. Cowan.)

Newell: What impact has your visual impairment had?

Cowan: Growing up with a visual problem, I often wondered what I could do for a living. What could be my contribution? Future prospects seemed uncertain and even bleak. However, involvement in programs of the Church and my study of the scriptures gave me a more hopeful perspective and outlook toward life. Perhaps out of necessity, I came to rely more and more on the Lord for direction and support. Two favorite passages from scripture that have helped me are Moroni’s explanation that “weakness” can help us grow (see Ether 12:27) and the Lord’s promise to lead us “by the hand” if we are humble and prayerful (see D&C 112:10). I have tried to live my life with “an eye of faith” (Alma 32:40).

Richard and Dawn at the Land and Records office at Nauvoo, Illinois. (Photo by Richard B. Crookston.)

Richard and Dawn at the Land and Records office at Nauvoo, Illinois. (Photo by Richard B. Crookston.)

Newell: What were some of the early pivotal moments of your life?

Cowan: Important milestones came along in my early life that were sources of encouragement. I received my patriarchal blessing when I was in high school. It has meant so much to me. Among other things, the patriarch said that I would wield my pen. I didn’t know what that meant as a high school kid. I thought of people signing bills and could not imagine that this is what I would ever be doing, but of course in hindsight I can see what he had in mind. That patriarchal blessing gave me guidance and hope. I always thought that being a patriarch would be a scary assignment, because of being in a position where you are expected to give that kind of inspired guidance to people. I can testify that now that I’m a patriarch, it in fact is a scary opportunity. But realizing the impact my own patriarchal blessing has had on my life, I consider it a great opportunity and awesome responsibility to give such blessings to others.

When I was in college, I had the special opportunity of receiving a blessing from President David O. McKay. This was an interesting experience. It was during the time that the Los Angeles California Temple was being built, and President McKay came to Southern California for some meetings in relation to that. I can remember wondering, Would it be possible to get a blessing from the prophet? I had not mentioned that to anyone. One evening, he addressed a gathering of youth from throughout Southern California, and the throng filled the large South Los Angeles Stake Center, so I reluctantly recognized that that would not be the occasion for me to realize my secret wish. The next night, however, he also agreed to speak just to our own stake youth group. The patriarch who had given me my patriarchal blessing (but who was now in the stake presidency) unexpectedly came up to me and said, “Richard, did you ever think you would like to get a blessing from President McKay? I think we can arrange it.” It happened, and I remember the long walk across the cultural hall and down the corridor, arm-in-arm with the prophet to the room where they had arranged for us to have this experience. Events like that gave me courage.

It was after my second year of college that I wondered if a person like me could go on a mission. I went in to see our bishop, and I was interested in his reaction. He said, “I don’t know, but why don’t we just fill out the papers and see what happens.” In those days, we had to be interviewed not just by our bishops and stake presidents but also by a General Authority. It happened that the next weekend was our stake conference, and we had a General Authority visitor, so within a week I had all three of those interviews. There were two important experiences that happened while I served in “la misión celestial” (it was the one true mission!), a Spanish-speaking mission in Texas and New Mexico. We had a General Authority visit every year. The first visit I experienced was when Elder Clifford E. Young, an Assistant to the Twelve, came after I had been in the mission about six months. We had to travel about 120 miles from Silver City to Las Cruces, New Mexico, where this conference would take place, where we would meet the visiting General Authority. My companion at the time was Melvin Hammond. I was his first missionary companion, and we had been together for several months at this point. I did not know at that point that Elder Hammond would be a future member of the Seventy and the Young Men president of the Church, but we enjoyed being together as companions. We rode in the back of a pickup truck for the 120 miles to get to this conference. It was on that occasion with Elder Young that I experienced such a neat feeling being with the Brethren and wondered, What could I do vocationally that would bring me into that kind of relationship? At that point I had been thinking of going either into teaching or law; I was a political science major because it could help me go in either direction. It was on that occasion that the impression came, Teach religion at BYU. That was the day I made that key decision. I have had the opportunity of being back in Las Cruces, where this took place, for “Know Your Religion” assignments, and I have told the people about the important event that happened for me in their community.

The other significant thing that happened as part of my mission experience was meeting Sister Dawn Houghton, who would later become my beloved eternal companion. I have a photo of a certain sister missionary standing next to me. We engineered it that way. It was inappropriate for an elder and sister to have a picture taken, just the two of us, so we had our companions step in for the photo.

Elder Cowan (center) and Sister Dawn Houghton (second from left), Spanish-American Mission, 1956. (Courtesy of Richard O. Cowan.)

Elder Cowan (center) and Sister Dawn Houghton (second from left), Spanish-American Mission, 1956. (Courtesy of Richard O. Cowan.)

After returning home and finishing my undergraduate schooling, in light of the decision that I had made to go into college teaching, I knew that I needed graduate degrees and that that would be a long course to follow.

On our way back to Southern California after attending a general conference, Dawn and I decided that we would go ahead and get married, and Dawn said that she would go to work to help support us. She has been my teammate ever since that time. We didn’t know how we were going to finance schooling, but she agreed that that was something she wanted to do, and I was grateful. As we got home that evening from the trip, there was a telegram waiting from the Danforth Foundation announcing that I had received the fellowship that I had applied for, which would pay our complete expenses through the PhD—tuition, room, and board, you name it—and the Danforth Foundation would support it. They are funded by the Ralston-Purina Company, so Wheat Chex quickly became our favorite breakfast cereal.

I received my bachelor’s degree in June 1958 from Occidental College in Los Angeles. Then just two months later, on August 14, Dawn and I were sealed as eternal companions in the Los Angeles California Temple. That fall we established our first home in Palo Alto, California, where I would pursue graduate studies in history at Stanford University.

Along the way, we had some remarkable experiences. I was receiving some service from an organization named Recordings for the Blind Inc. They provided recorded versions of textbooks, and I received a letter one day that I thought was saying that the book I had requested was being recorded and would be sent soon. In fact, the letter announced that they were giving four $500 cash awards. I said to Dawn, “We ought to apply for one of those.” Then the next paragraph said, “You have been chosen to receive one.” I said, “Wonderful, we don’t need to apply!” The next paragraph added, “It will be presented to you by President Dwight D. Eisenhower at the White House in Washington, DC, and we’ll take care of your expenses.” With a smile on my face, I asked Dawn, “Do you think we ought to go?” We decided to make that a missionary experience any way we could. I think it worked out, because about three weeks after that there was an article in Time magazine reporting the awards, and the only religion that was mentioned in the article was that Cowan was a Mormon from Salt Lake City. Actually, Cowan was a Mormon from California, but I thought they got the important part right.

We were at Stanford for three years. At the end of the first, I received my master’s degree; it was called the “bread and butter degree,” and we were encouraged to get it along the way just in case we did not make it to the doctorate. Fortunately, I was able to finish coursework requirements the second year and then complete my dissertation during the third.

Newell: How did you become a professor at BYU?

Cowan: Well, although it was my goal, there were discouragements along the way, of course. I had the opportunity to visit with one of the leaders of the Church Educational System. He happened to be in Southern California when we were there for a visit, and I talked with him about my hopes of teaching. He said, “Well, a person with your disability just wouldn’t be able to make it in the classroom.” It was very discouraging counsel, but we decided to press forward nevertheless. As the Lord states in Doctrine and Covenants 59:21, his hand is in all things. In other words, he has a plan for us—not predestination—but his help is guiding us along the path that will lead us to our destination. I think getting the Danforth Fellowship was certainly an example, because that brought us in contact with Dan Ludlow, who was a member of the BYU faculty at that time. Brother Ludlow was the person who made it possible for me to be here. The Ludlow family has made a great contribution to Religious Education—certainly to me personally. It was an act of faith on the leadership’s part to give someone like me a chance to join the faculty.

I still remember the interviews we had with President Wilkinson prior to being appointed. It was right in the middle of his budget hearings, so I knew that he was otherwise occupied. I remember that he asked me about my political attitudes. Next, I needed an interview with a General Authority, and it was to be Elder Harold B. Lee. The one question that I can remember from that interview was “Can you build faith among the students you will teach?” I said, “I don’t know, but that is certainly what I intend to do.” Later I heard him say to President Wilkinson, “I wish all the young men you bring to me were as faithful as this one.” So fortunately we did have the opportunity of coming to BYU.

When I arrived, David Yarn was the dean. I remember him as a wonderful Southern gentleman. Dawn and I were living in a basement apartment just off the hill [in Provo], and after a few weeks we found out that Dean Yarn was selling his home. Brother Ludlow had told us the one true ward in Provo was the ward he lived in, and it happened to be the same ward where Brother Yarn’s home was. We looked at it and decided to buy it; we have lived in that ward ever since. The kitchen was a very dark color and the Yarns agreed that they would help us paint it with a more cheerful color. While we were working on that project, I remember visiting with Dean Yarn about what should be my focus. We decided, given my background and interests and the needs of the faculty, that recent Church history would be an appropriate area. That’s been one of the areas that I have focused on over the years. You can see that there were these little turning points along the way. My first semester here I taught the Doctrine and Covenants and Book of Mormon. The Doctrine and Covenants became another area that I have focused on over the years.

Although I knew that I was on trial, almost from the beginning I began to get signals that I was passing the test. I was given committee assignments and other opportunities, and then the rank advancement came along. Receiving word of rank advancement, plus being awarded BYU’s Professor of the Year let me know that I had passed the trial. It was a completely different world than now. Back then, I just got a note with my contract saying, “You are now an associate professor.” That’s the way it happened; no application, no portfolio.

Newell: How have you handled normal day-to-day classroom teaching? And how has teaching changed over the years?

Richard lecturing shortly before retirement. (Courtesy of BYU Religious Education.)

Richard lecturing shortly before retirement. (Courtesy of BYU Religious Education.)

Cowan: I decided that I should just level with the students, and so I told them I would not be able to see them if they raised their hand; I invited them simply to speak up if they wanted to make a comment or ask a question. Over the years, I have told stories about myself during the first two or three meetings with each class. A favorite one, which is a true story, is that when I was a missionary, our district president told us that a few months earlier he got the thought that the missionaries did not know the scriptures well enough, so he decided to have a scripture contest. I thought he might be planning to do the same thing with us, so I went to a stationery store and bought a binder. In it, I put pages on which I listed in Braille the scriptures we used in our teachings, the ones out of the proselyting discussions. Well, we did have the contest. I did all right; I was able to answer his questions, and he said, “Elder Cowan, where did you get all those scriptures?” I had worked at it. One day we went to an appointment, and not only was our investigator waiting for us, but his minister was there with him. There followed what we missionaries called a “friendly discussion.” He said, “All right, Mormon elder, give me a few references on that point.” I was sitting there with my hand inconspicuously inside my little book, and when he said “Give me some references,” I did—quite a few. And he was impressed. He said, “My, Elder Cowan, you know the scriptures well,” and I said, “Yes, Reverend, I have them at my fingertips.” I have told that story to the students and just say as a reminder, “Don’t raise your hands, just raise your voice and we’ll get along just fine.”

One general lesson that I have learned: In the early days, some of my colleagues referred to class meetings as lessons. At the time I did not appreciate that; I thought it sounded too much like junior high school. Yet over the years I have come to appreciate that the main contribution we make is not just in information but the ability to think more deeply. Perhaps different from other parts of the university, our main contribution is conversion to the gospel of Jesus Christ—building faith as Elder Lee had challenged me to do. So I don’t mind as much anymore if what I do in the classrooms is referred to as lessons instead of discussions. I have come to appreciate what we have really been appointed to do here.

Another interesting observation for me is to see how technology has developed. For example, writing my dissertation at Stanford was an example of how Dawn and I were a team. We had prepared the rough draft, and so she dictated and I typed. Yes, I was my own typist. Back then, there were no adequate photocopy methods. Today you can make one original and then make quality photocopies, or do it on the computer and print any number of original copies you need. We had to use carbon paper, putting six pages in the typewriter at once. We had a manual—not an electric—typewriter. Between each of these pages was a sheet of carbon paper which had ink on one side, so when we typed on the front page, it printed through to the other copies. We were told the university graduate office would tolerate no erasures. There was easy-erase paper that would make it possible to correct easily, but that was not permissible because it was not permanent. We had to type it perfectly. At that time, the style was footnotes, not endnotes, so on every page we had to calculate how many lines we would need for footnotes—in other words, where to stop the main text. (I think it’s ironic that now that computers would do all that for us, we use endnotes instead.) Furthermore, inserting new material would throw off all remaining page breaks, meaning we would need to type them over.

Here’s another example. When we came to BYU, we found that the way students registered for classes was to go down to the field house (this was before the Marriott Center). On the playing floor, all the departments had tables set up with class cards. The seniors would be given first preference and so forth; then the students would stand in line and pick up a card that meant that they were admitted into the class. Faculty members had to be there to hand out those class cards, so we should be grateful that now registration is by computer.

Also, just a note about how visual aids reflect advances in technology: When I went to class during my first years, I carried large posters that I stood on the chalk tray in the front of the room as the discussion progressed. Of course, other teachers could draw their diagrams directly on the board as they taught. Then the next big new thing was the overhead projector. What a nice thing it was to just put a few transparencies in my notebook instead of having to carry the large poster boards to class! Then more recently it has become even better with a flash drive that we can carry in our pockets to class. Some faculty members go online and have something set up on the Internet and don’t even have to take a flash drive to class. It has been interesting to see how technology has improved over the years in so many different ways.

Another thing that’s changed is the organization of Religious Education. When I came we had five departments: Bible and Modern Scripture, Biblical Languages, Theology and Church Administration, History and Philosophy of Religion, and Religious Education. I don’t know what it would have been like to be the department chair of Bible and Modern Scripture. It sounds like that department would have included just about everything. Having Church History and Philosophy combined together in one department also seems strange today. The five departments lasted for only about two years. Then in 1963 there were just two departments—undergraduate and graduate, plus philosophy. (Philosophy was part of Religious Education until 1973, when it was transferred to Humanities.) Apparently there was enough of a graduate program in religion at that time to warrant a separate department, but still you can guess that all of the work was being done in the undergraduate studies in religion. People often ask me when our current two-department system started. In 1969, we launched Ancient Scripture and Church History and Doctrine.

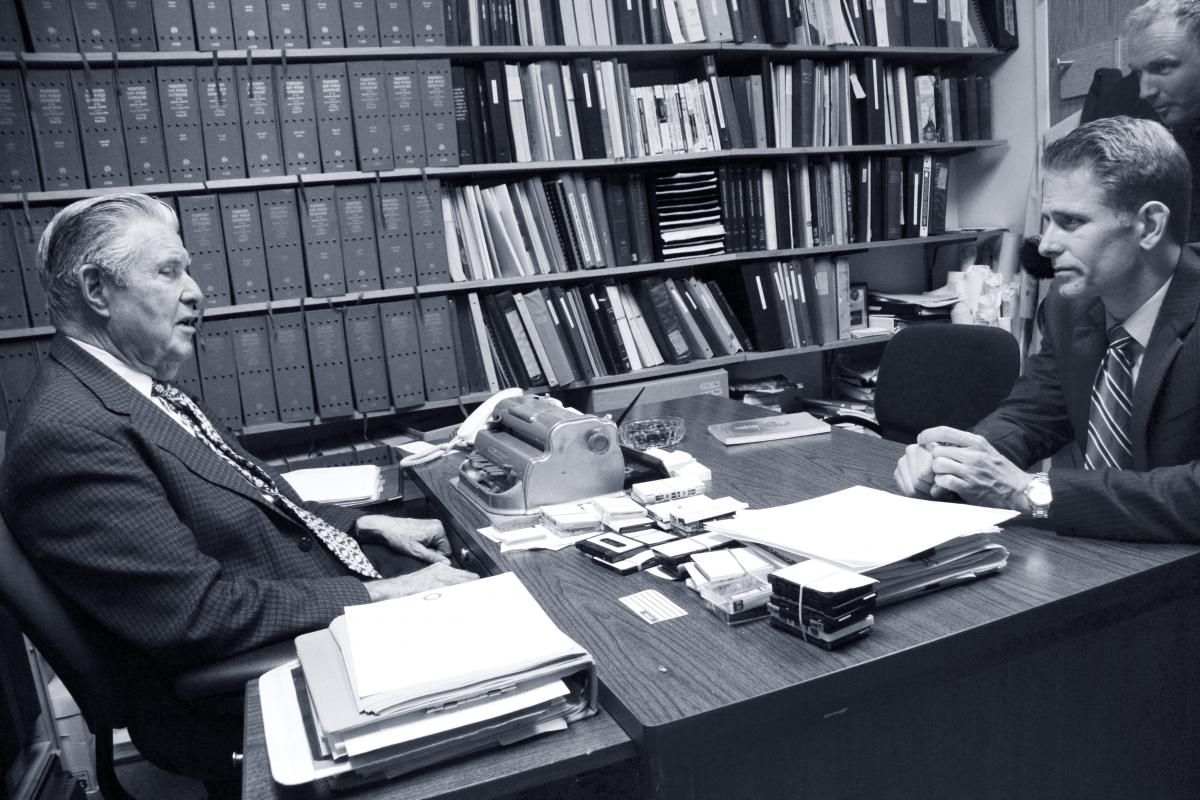

ABC-Television reporter Noah Bond interviewing Richard for a human interest story. (Photo by Brent R. Nordgren.)

ABC-Television reporter Noah Bond interviewing Richard for a human interest story. (Photo by Brent R. Nordgren.)

Newell: What are some of the things you have enjoyed most about being a BYU Religious Education faculty member?

Cowan: One of the great opportunities for me has been travel. Over the years, going on Education Week assignments was our annual family trip. There used to be Education Weeks in lots of different locations, especially in the West. We would go to a town and be there for three days for the program. While I was giving classes, the family could be out visiting points of interest or swimming at the motel pool. It was during such an assignment in Riverside, California, that I first met Robert J. Matthews several years before he joined our faculty [he later served as dean of BYU Religious Education from 1981 to 1990]. Travel assignments often provided opportunities to get to know fellow faculty members on a more intimate level. For example, I cherish memories of personally walking with Kelly Ogden in Jerusalem and with Brent Top around Copenhagen.

Perhaps because I could not see exactly where we were going, I had a greater desire to feel oriented. Therefore, before going on these trips, with the assistance of Dawn or my helpers in the office, I made raised-line or Braille maps of the places we were going. I just felt more secure knowing where things were and how to get there. I have had the unique opportunity of giving sighted people directions in such diverse places as Southern California, Mexico City, and Jerusalem.

Religious Education sponsored two sabbatical trips that were unique. Back then, every faculty member was entitled to a sabbatical leave, meaning that every seven years you could either have a full year off at half pay or a half year off at full pay to go and study or do whatever you needed to do to renew yourself. Dan Ludlow developed a concept of a two-month sabbatical in which we would travel to some significant areas such as Bible or Book of Mormon lands. In 1968 we went to the lands of the Bible, in 1974 to the lands of the Book of Mormon. So the amount of money that the university would put into a sabbatical covered the expenses of those trips. We were even given pay as if we were teaching for those two months, and that helped us take our companions with us. That was a unique experience. I guess it was sort of a forerunner to the regional studies that the Department of Church History and Doctrine has sponsored. What a great blessing that has been to me.

Richard traveling with his wife, Dawn, as part of a 2012 Regional Studies trip. Richard has loved trains all his life. (Photo by Richard B. Crookston.)

Richard traveling with his wife, Dawn, as part of a 2012 Regional Studies trip. Richard has loved trains all his life. (Photo by Richard B. Crookston.)

Newell: Tell us about some of your colleagues and mentors in teaching religion.

Richard with Professor Susan Easton Black, who worked across the hall from him for many years. (Courtesy of BYU Religious Education.)

Richard with Professor Susan Easton Black, who worked across the hall from him for many years. (Courtesy of BYU Religious Education.)

Cowan: I have been keeping a list of the faculty members as part of my responsibility as historian for Religious Education and have put together a little booklet, Teaching the Word. I am number 41 on that list. Currently, the total is up to 191 people who have served as full-time members of the BYU religion faculty. All but the first few have been colleagues whom I have known personally. Seven of the first nine had left before I came. The other two—Sidney B. Sperry and Hugh Nibley—were still here and continued for a number of years. I remember Brother Sperry as being just a wonderful gentleman. Today we talk about having mentors. We didn’t have any assigned mentors at that time, but he was that to all of us. He was available to help in any way. The one memory I have of Brother Nibley is that Religious Education would schedule a temple session from time to time, and Brother Nibley would meet with us after the endowment session in the temple and talk about his research and insights on temples in the ancient world. Of those other nine, there were two of them who left before I came but who later came back—Alma Burton and William E. Berrett—and they became colleagues. That leaves only five of the 191 who have not been colleagues of mine during my fifty-three years on the faculty.

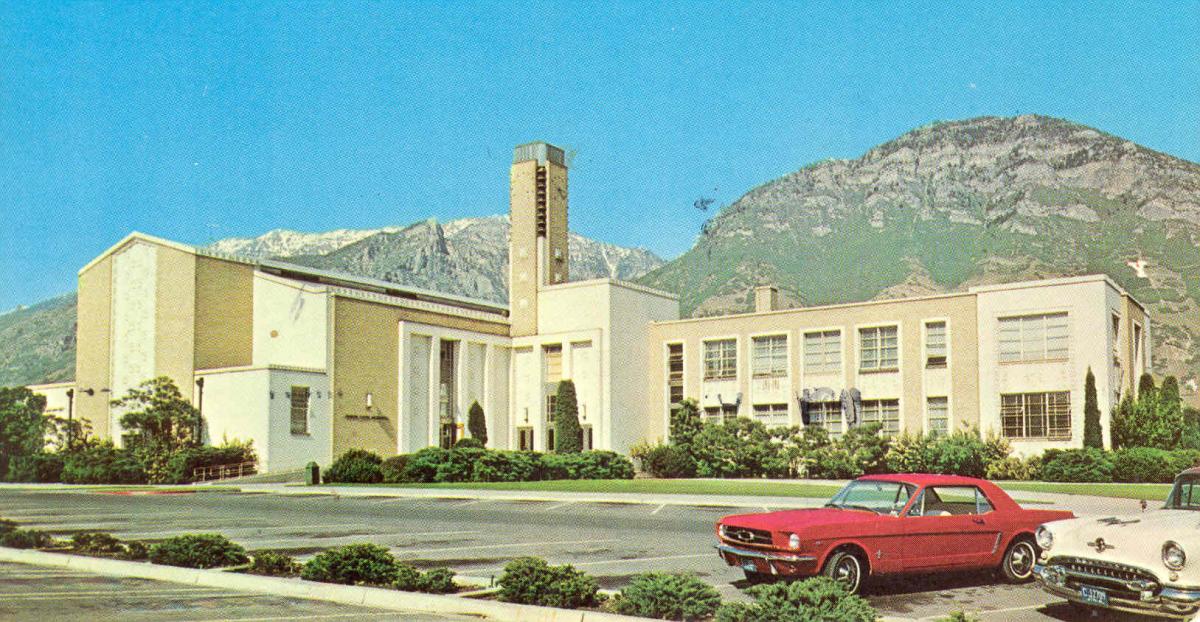

Richard worked in the original Joseph Smith Building from 1961 until its closing. (Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.)

Richard worked in the original Joseph Smith Building from 1961 until its closing. (Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.)

Newell: As you look back on over a half century at BYU, what are some of the experiences that stand out in your memory?

Cowan: During the fall semester of 1989 I taught at the BYU Jerusalem Center. I found it spiritually exciting to walk where Jesus walked. I gained a greater understanding of Holy Land geography and the relative location of key features as we traveled around the country and walked over such significant sites as the Temple Mount. I appreciate how fellow teachers and others on the Jerusalem Center staff helped me get prepared to conduct field trips. This was an unforgettable experience to share with Dawn and with our youngest two daughters.

On April 3, 2007, I had the great privilege of speaking at the campus devotional in the Marriott Center. I reflected on the significant and exciting developments that had occurred in the Church generally, and specifically at BYU during the nearly half a century since we came to Provo. I was conscious that this day marked 171 years since Elijah had restored his keys, so I focused on particular developments in temple building and activity.

That same month, I began teaching spring term at BYU–Hawaii. I gained a new appreciation for how BYU–H is building bridges with countries in East Asia, including mainland China. Over the years, I have sought to identify “special students,” such as those for whom English is a second language, very recent converts, or members of other faiths. There might be two or three in a typical class at Provo, but in Laie almost entire groups fit into one or more of these categories. Insights from this experience led me to be more sensitive as I planned course requirements even here in Provo.

From 1994 to 1997, I served as chair of the Department of Church History and Doctrine. I enjoyed working with colleagues and supporting their teaching and scholarship. Being a member of the Administrative Council gave me the feeling of being a part of and a contributor to decisions affecting Religious Education. I am so grateful for the many opportunities afforded me as a faculty member at BYU, and I hope I have made some contributions.

During a 2012 faculty visit to Echo Canyon, Dawn and Richard hiked up to Cache Cave with the rest of the department faculty. Cache Cave was used by General Daniel H. Wells, a member of the First Presidency, during the Utah War (185758). (Photo by Richard B. Crookston.)

During a 2012 faculty visit to Echo Canyon, Dawn and Richard hiked up to Cache Cave with the rest of the department faculty. Cache Cave was used by General Daniel H. Wells, a member of the First Presidency, during the Utah War (185758). (Photo by Richard B. Crookston.)

Newell: How did you become interested in and an expert on LDS temples?

Cowan: It all started during my youth in Southern California before we had a temple there. We went on temple excursions, two or three days to Mesa or St. George, when we youth could do our baptisms for the dead quickly and then had to wait for the adults who were doing the endowments. It gave us a chance to be together and associate with others who had common interests and ideals. I think that’s where my love of temples started.

The construction of the Los Angeles California Temple started just before my mission, but the temple was completed while I was on my mission, and the dedication was supposed to occur just a few weeks before I was due to be released. One of the General Authorities came on his annual mission tour, and I asked, “Is there any possibility I could get permission to go home and attend the dedication?” I explained how I had looked forward to it all my life. I emphasized, “I love my mission; I will be happy to come back and finish here.” He responded, “Elder Cowan, they will be able to dedicate the temple without you.” As things worked out, there were some delays, and I got home on a Tuesday evening and the temple was dedicated the following Sunday. Thus I was present for the dedication of temple number 10, and then after coming here to BYU we witnessed the construction of the Provo Temple, which was temple number 15. I don’t know the number that the Provo City Center Temple is going to be, but it’s going to be very close to number 150. I think it’s interesting that there has been a tenfold increase in temples during the time that I have been here on the faculty.

One of my scariest experiences in relation to a temple was when we were attending the San Diego California Temple dedication, and without any advanced warning, President Thomas S. Monson called on me to speak. I gave an impromptu talk on how various features of our temple experience help us sense that we are leaving the world and entering a more sacred environment. That was an experience I will never forget! Still, I love temples—not because of those unique experiences but more because of my day-to-day attending the temple and feeling the Spirit as we serve there.

My research and teaching on this subject has helped me realize how the Lord has guided the building of temples. One example was selecting the site for the Swiss Temple; the site they were originally considering, but could not get, turned out to be right in the middle of a highway that went through, so it would not have been suitable at all. Other examples include being able to come up with the amount to offer for the New Zealand site, which was the exact figure—to the cent—that the owners were thinking might be a fair price. The design of the temples is yet another example. We are familiar with the First Presidency seeing the Kirtland Temple in vision, the Prophet Joseph seeing how the Nauvoo Temple would appear with lights in the windows, and Brigham Young’s vision of the Salt Lake Temple, with its symbolism of the Melchizedek and Aaronic Priesthoods in the two sets of three towers. One example that you may not be acquainted with is in relation to our own Provo Utah Temple. When Emil Fetzer received the assignment to design it and the Ogden Utah Temple, of course it was overwhelming to him. He was talking to a fellow member of the Church building committee about this significant assignment while they were flying across the Atlantic. As he discussed this matter, he said he seemed to see the interior of the temple—where the recommend desk should be, other facilities on the main floor, and then the sealing rooms on the second floor. He was especially impressed with the arrangement of the celestial room and six surrounding ordinance rooms on the upper floor. So when he got back to his office, all he had to do was put down on paper what he had seen. He then clothed these rooms with the outside wall. The idea that the temple was specifically designed to look like a cloud by day and pillar of fire by night is not accurate, although it is meaningful to many people. But he did receive inspiration for his design.

I worked on a history of the Oakland California Temple that was published in 2014 by the Religious Studies Center, for which I am most grateful. The temple was dedicated in 1964, and in my research I have felt the need to be accurate, especially of faith-promoting accounts. For example, an experience the Saints in the Bay Area repeat often is that while Elder George Albert Smith was attending a Boy Scout conference at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco during the 1920s, he was meeting with the president of the small branch in Oakland. That to me sounded fishy. Why would a member of the Twelve be meeting with the president of a small branch? While they were meeting, he told this branch president, “You know, I can envision, on those East Bay hills, a beautiful white temple that will be a beacon to everybody in this area.” He said it could be seen from the Golden Gate Bridge and so on. The Saints became what they called “hill watchers,” watching for the time when the temple would be built on those hills. I thought I wanted to confirm that story. The first thing I did was to check Elder George Albert Smith’s diary, which unfortunately is not complete during that period of time. The parts that are available do not mention a trip to California, so I wondered if we had on our hands another “faith-promoting rumor.” Then my research helper found in the Church History Library a picture of a meeting of Boy Scout leaders at the Fairmont Hotel, and Elder George Albert Smith is in the front row, third from the right end, so that confirmed the circumstance for this vision, but with just a different date. That was important because during the interval between the time the story was supposed to have happened and the time we believe it really took place, about two or three years, this branch president had been called by Elder George Albert Smith to become the first president of the San Francisco Stake. Just a few months later, Elder Smith was back on Boy Scout business and probably wanted to meet with that new stake president to see how things were going, so this timeline makes sense.

People ask what I am going to be doing following retirement. I have all of these projects that still need to be completed, and I hope that from time to time I might have the opportunity to teach some classes as needed.

Young Richard visiting the construction site of the Los. Angeles California Temple in mid-1950s. (Courtesy of Richard O. Cowan.)

Young Richard visiting the construction site of the Los. Angeles California Temple in mid-1950s. (Courtesy of Richard O. Cowan.)

Newell: What are some of the lessons you have learned from teaching about the history of the Church?

Cowan: I have learned that the leaders and members of the Church are not perfect but that our Heavenly Father uses us to further his work and that he is guiding us. When we study the Bible, we can see how the prophets were instruments in his hands to bless the people. I’m pleased to say that the same thing has been true with the history of the Church during the twentieth and now twenty-first centuries—the areas that I have been specializing in. We don’t need to be afraid of our history. The more we learn about it, the more convinced I am that we can see God’s hand leading his kingdom on earth.

I have also learned that we don’t just tell faith-promoting stories without confirming their accuracy, as I mentioned earlier. For example, I shared one about finding a site for the Church school near Mexico City, and my source was an eyewitness who was a high official in the Church Educational System. I shared that story down in Mexico at an Education Week one time, and somebody right in front of me brought his fist down on the desk and said, “That isn’t the way it happened!” I then asked him to tell us what really took place. I did some follow-up research, and I agreed that my story was wrong, even though I had an eyewitness who was a high official as my source.

Here are some examples of experiences we have verified. I had the privilege of being on David Boone’s master’s thesis committee when he did his study on the evacuation of missionaries from Europe at the outbreak of World War II. We confirmed stories that I had heard about a missionary who had to locate elders to give them funds to buy tickets to get out of the country when the evacuation was being ordered. The mission president said there were thirty-one missionaries that he could not account for, and he directed Elder Norman Siebold to go find them. It turned out that fourteen of the thirty-one had in fact made it safely out of the country. That left seventeen that needed help. Elder Siebold felt impressed to take a train and get off at certain stations, then take another train to a different location, not knowing where the missionaries would be. In Cologne he jumped up onto a baggage cart and started whistling “Do What Is Right,” which was their mission song, and found missionaries. He located all of the seventeen.

Another one: At the close of World War II, the Church wanted to reopen Japan. We had missionaries in Japan until 1924, but frankly the mission was not that prosperous, and so it was closed. Still, following World War II, the leaders of the Church were impressed to open the mission again, so we made application and were told by military authorities, “We don’t want to destabilize, and we don’t want new religions; we just want to keep things on an even keel. If you had been here before World War II, we might have entertained your application.” We responded, “We were here; we were here until 1924.” They said, “But you left!” It so happened, however, that in 1938, President Heber J. Grant had felt impressed to send someone back to Japan to tell the members, “We will be back as soon as we can.” The person he sent was the former mission president who had been there in 1924. In those fifteen years, many people had moved and others had died and some had apostatized; he did not know where to look. He thought, There is one sister who is more likely to have kept in touch with everybody else—if he could just find her. He knew that she lived in Yokohama, which is a major industrial city. He thought, I don’t know where she is, but I’ll try to find her. He checked into a hotel, stepped out onto a busy sidewalk, and momentarily paused, deciding which way to turn: Do I go to the city hall or the police department? Where do I start? A young girl stepped up to him and said, “Sir, who are you looking for?”—sort of an unusual question. You would think he would say, “I just need to go to city hall and check on someone’s address,” but he said, “I’m looking for so-and-so.” This young girl said, “She’s my mother.” Of all the thousands of people on that sidewalk that day, the fact that those two met was not a coincidence. The mission president was able to contact the Japanese Saints and assure them that as soon as conditions were right, missionaries would return. This in turn prompted postwar officials to give the Church permission to reopen its mission. The history of the Church in recent times is full of that sort of thing.

Also, I have learned that the prophets see afar off. President Grant emphasizing the Word of Wisdom helped prepare the Saints for a time when drugs would become a major issue. In 1937, when he was visiting the branches in Europe, he said, “You folks need to assume responsibility for your own leadership.” At that time, the missionaries did everything. It was just two years later that the missionaries were withdrawn, and so what timely counsel that was. The family is another example, as the family proclamation was issued in 1995 before same-sex marriage became such a hot issue. Our prophets have prepared us. They don’t necessarily predict the future, but they certainly help us prepare for it.

Richard and his wife, Dawn, at Devil's Gate, Wyoming, pull a handcart as part of a 2012 Religious Education faculty trip. (Photo by Richard B. Crookston.)

Richard and his wife, Dawn, at Devil's Gate, Wyoming, pull a handcart as part of a 2012 Religious Education faculty trip. (Photo by Richard B. Crookston.)

Newell: How do you think you have changed over the years?

Cowan: I believe I am less dogmatic about things that don’t matter. When I look at my exams written years ago, I realize that I am not as sure about certain facts or interpretations as I once was. I respect the discoveries of science, such as in relation to the history of the earth, and I certainly accept statements in the standard works and by living prophets on that subject. Sometimes there appears to be a conflict, but there can be no conflict between that which is true in science and that which is true in religion. In Doctrine and Covenants 101:32–34 we read that the Lord will reveal all things, including how the earth was made (that certainly is a seminar I plan to attend). If he is going to reveal that, I assume that means we do not have all the answers now. In the meantime, I am willing to be more tentative in my statements. I find it much easier now to be humble, yet at the same time certain, about truths I do know and teach them with faith and power.

Whenever he visits a historical site, Richard experiences the history firsthand. Here he is shown feeling the ruts made by thousands of pioneer wagons. (Photo by Richard B. Crookston.)

Whenever he visits a historical site, Richard experiences the history firsthand. Here he is shown feeling the ruts made by thousands of pioneer wagons. (Photo by Richard B. Crookston.)

Newell: Any final thoughts upon your retirement from BYU?

Cowan: I had always assumed that I would retire when I turned sixty-five. About ten years before that time, however, I learned that the university had adopted a new policy that did away with the mandatory retirement age, so I decided to stay a while longer. I have thoroughly enjoyed the privilege of continuing my service at BYU.

Some people look forward to retirement, saying, “I can hardly wait until I don’t have to do this job anymore.” I have never thought of what we are doing here in Religious Education as work. Dawn can testify that I don’t use the phrase “I’m going to go to work” or “after work.” I just don’t think of it in those terms. I think of teaching and researching and meeting students, and I have loved what I have done. And just as Brothers Nibley and Sperry made a contribution to me as a junior faculty member, we all want to be of help to new members of the faculty today. Also, I would not have stayed all these years without the valuable help of countless student assistants, the support of my colleagues, and of course my beloved wife and family.

Having the Brethren come visit us personally from time to time helps fulfill the vision of my future career that I had many years ago as a young missionary. I testify that we are helping to build the Lord’s kingdom. I pray the Lord’s blessings will be with this important work as we are helping prepare the world for his Second Coming.