Amos through Malachi: Major Teachings of the Twelve Prophets

Blair G. Van Dyke and D. Kelly Ogden

Blair G. Van Dyke and D. Kelly Ogden, "Amos through Malachi: Major Teachings of the Twelve Prophets," Religious Educator 4, no. 3 (2003): 61–88.

Blair G. Van Dyke teaches in the Church Educational System and was an instructor of ancient scripture at BYU when this was written.

D. Kelly Ogden was a professor of ancient scripture at BYU when this was written.

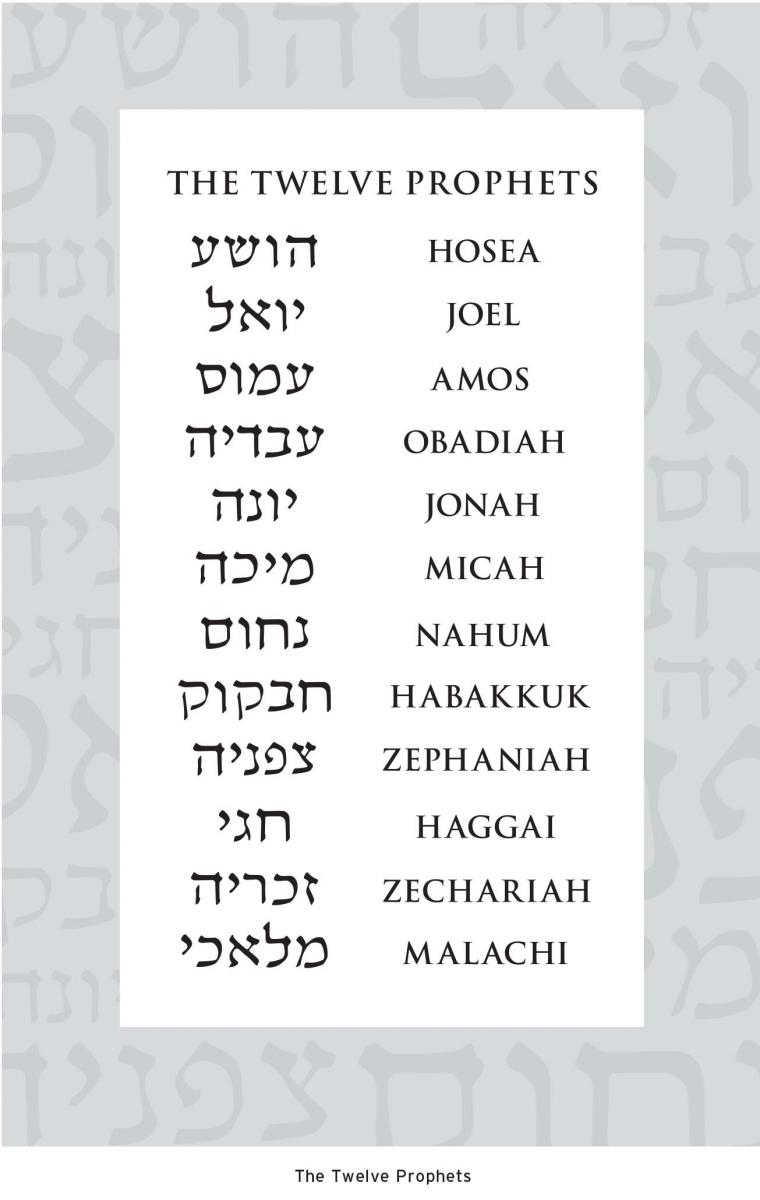

The Twelve Prophets

The Twelve Prophets

The writings of Amos through Malachi are frequently skirted as blocks of scripture to be quickly dealt with toward semester’s end after the “important” writers of the Old Testament have received more careful and thoughtful treatment. Such a course is lamentable because these prophets consistently prophesied in days of great wickedness among God’s people—when they indulged in priestcraft, sorcery, and idolatry and when they mistook outward symbols of covenants for heartfelt, sincere worship. In this regard, the parallels between their days and ours are striking. Following a brief introduction to the writings of these twelve prophets, this article will explore some of the major teachings within their historical and spiritual context. We anticipate that this will lead to a greater desire and a greater capacity to integrate into religious education the principles of the gospel contained in the writings of the twelve prophets.

The Book of the Twelve

Anciently, the writings of these twelve prophets [1] comprised one book known as the Book of the Twelve and were included in the Old Testament canon as such. The earliest acknowledgment of the significance of their writings comes from the Wisdom of Jesus, Son of Sirach, a book written early in the second century BC and now included in what we call the Apocrypha. It says, “May the bones of the Twelve Prophets send forth new life from where they lie, for they comforted the people of Jacob and delivered them with confident hope.”[2] For us, the most compelling evidence for the continued value of the writings found in the Book of the Twelve may be that they have been quoted extensively over the past two millennia and on significant occasions. Some examples include Stephen’s quoting Amos 5:25–27 as part of his stinging rebuke of the Sanhedrin just before his martyrdom (see Acts 7:42–43); the Savior’s inclusion of Malachi’s writings to the scriptural canon of the Nephites, explaining that “it was wisdom in him that they [Malachi’s writings] should be given unto future generations” (3 Nephi 26:2); the Savior’s quoting several passages of Micah during His Nephite ministry (see, for example, 3 Nephi 20:18–19); Moroni’s recital of portions of Joel and Malachi to the Prophet Joseph Smith in September 1823; and, finally, the citing of Joel and Zechariah in the Doctrine and Covenants (see D&C 45:40–42, 51).[3] These and other examples illustrate that the writings of the prophets in the Book of the Twelve have been highly valued for over two thousand years.

We will now survey the historical background of the twelve prophets and consider some of their major teachings in chronological order.[4]

Sick, Decrepit, and Broken: The Rise and Demise of Israel in the Eighth Century BC

With the eighth century BC came a period of wealth and prosperity to the kingdoms of Israel and Judah unknown since the monarchy of David and Solomon. Israel’s former enemy, Damascus, was recuperating from crushing blows by Assyrian King Adad-nirari, allowing Israel to escape the weight of Syria’s heavy hand (see 2 Kings 13:5). Assyria, in turn, was weakened by internal struggles and threatened by the rising powers of the neighboring kingdom of Urartu. Israel capitalized on the absence of a dominant foreign military force by recapturing territory and trade routes previously lost to Damascus (see 2 Kings 13:25). Judah was able to do the same, recovering lands that had been lost to Edom.

Following her victories, Judah, under the reign of King Amaziah, rashly rose up against Israel. This was nearly fatal because Israel, led by King Joash (Jehoash) invaded Judah and defeated her armies at Bethshemesh. Joash then drove his armies to the heart of Judah, broke down the northern wall of Jerusalem, looted the temple and royal palace, and took King Amaziah prisoner. Amaziah was eventually freed and allowed to regain his throne but as a vassal of the king of Israel. On the heels of these embarrassments came plots to remove Amaziah from the throne. In response, he fled Jerusalem only to be overtaken and assassinated at Lachish, leaving his son Uzziah (Azariah) to reign in his stead (see 2 Chronicles 25).[5] Meanwhile, Jeroboam II (son of Joash) assumed the throne in Israel (see 2 Kings 14:23).

The chroniclers note that Uzziah (783–742 BC) and Jeroboam (786–746 BC) each reigned for about four decades. During this time their military expansion was impressive. As mentioned above, Uzziah regained firm control of Judah’s southern territory and rebuilt the port at Ezion-geber (Elath; see 2 Kings 14:21). At the same time, Jeroboam expanded the northern border of Israel to “the entering of Hamath” (2 Kings 14:25) beyond Damascus. A similar expansion eastward into transjordanian regions may be safely assumed.[6] From north to south the combined land holdings of Israel and Judah rivaled those held by Solomon two centuries earlier. It was a time of great confidence, open trade, and wealth. Unfortunately, this prosperity led Israel (even more so than Judah) to swell with pride, merge iniquitous pagan rites with the worship of Jehovah, and embrace opulence and materialism at the expense of social justice for the poor. By the mid-eighth century, the true worship of Jehovah in Israel was a mere shadow of its legitimate self. External ritual, laden with watered-down conviction, replaced deep and meaningful worship. Even so, Israel continued to prosper and accumulate wealth, all the while claiming promised blessings of protection from Jehovah that were reserved for the righteous. The people of Israel were convinced that material prosperity was an absolute sign of God’s pleasure resting upon them, yet the northern kingdom of Israel was sliding rapidly toward her destruction at the hands of Assyrian forces in 721 BC. Under these circumstances, Amos, Hosea, Jonah, and Micah ministered.

Amos

The prophet Amos was, before his call to be a prophet, “among the herdmen of Tekoa” (Amos 1:1). While Amos spent his ministry among peoples of the northern kingdom of Israel, Tekoa lies deep in the tribal lands of the southern kingdom of Judah (about six miles southeast of Bethlehem and twelve miles from Jerusalem). Amos provides an account of his call to minister in Amos 7, explaining that “I was no prophet, neither was I a prophet’s son; but I was an herdman, and a gatherer of sycomore fruit: and the Lord took me as I followed the flock, and the Lord said unto me, Go, prophesy unto my people Israel” (Amos 1:14–15).[7]

Amos is to Israel in the seventh century BC what Jeremiah is to the kingdom of Judah one century later. Both are known as prophets of doom.[8] The tone of Amos’s ministry is set in the initial lines of the book. Amos forms in the reader’s mind the image of a roaring lion ready to pounce on a foolish and helpless victim. This imagery evokes a sense of God’s frustration with Israel and her neighbors (see Amos 1:2). The words of Amos are not soft, kind, or gentle; rather, they are ferocious and filled with yearnings for justice. This is because Israel knowingly turned away from God. Additionally, Israel’s neighbors Damascus (to the northeast of Israel), Gaza (southwest), Tyrus (north), Edom (southeast), and Ammon (east) are condemned for their wickedness and listed by Amos as soon-to-be recipients of God’s wrath. This listing of nations provides a visual, wherein Israel is surrounded on all sides by idolatry and gross wickedness. This, however, is not the great calamity of Amos’s day. The problem is not that northern Israelites are surrounded by wickedness but that, like their neighbors, they have become wicked themselves. God’s people are supposed to withstand such pressures. For example, Noah was surrounded by wickedness, refused to embrace it, and was lifted above it in the ark (see Genesis 7:17); Abraham did the same, allowing him to become a “greater follower of righteousness” (Abraham 1:2); Moses was surrounded by wickedness and bondage yet shunned the worldliness of Egypt and was led away and allowed to ascend the mountain of the Lord in Sinai (see Exodus 19; Hebrews 11:24–29). Unfortunately, Israel, in the days of Amos, typified the world.

Amos provides a troubling catalog of Israel’s sins (see Amos 2–9). Like a prosecuting attorney hungry for justice, Amos hurls accusations at Israel at a dizzying pace.[9] But two sins are dominant in his appeal to God for a swift judgment against Israel. First, the Israelites have turned from Jehovah to idolatry. “But let judgment run down as waters, and righteousness as a mighty stream. Have ye offered unto me sacrifices and offerings in the wilderness forty years, O house of Israel? But ye have borne the tabernacle of your Moloch and Chiun your images, the star of your god, which ye made to yourselves” (Amos 5:24–26; see also 2:8; 8:14). Second, they have severely treaded upon the poor. “Hear this word, ye kine [cows] of Bashan, that are in the mountain of Samaria [capital of Israel], which oppress the poor, which crush the needy, which say to their masters, Bring, and let us drink” (Amos 4:1; see also 2:6–7; 5:11; 8:4–5). The burden of these sins is felt so keenly by Amos that he declares: “Behold, I am pressed under you, as a cart is pressed that is full of sheaves” (Amos 2:13).

Amos offers no hope to ancient Israel. The die is cast; their doom is sure. “The end is come upon my people of Israel” (Amos 8:2). Their inheritance includes howling, mourning, famine, sifting, destruction, and death by the sword (see Amos 8:1–12; 9:1–10). Amos concludes his call for justice by proclaiming that Israel “shall fall, and never riseup again” in antiquity (Amos 8:14).

All of these prophecies of doom were fulfilled within a few decades of Amos’s ministry to Israel. The writings of Amos depict God as one who is offended by rebellion. More to the point, He loathes spiritual infidelity and any abuses of the disadvantaged, poor, and downtrodden. Guilty people may expect the justice of God in full measure. Nevertheless, in a pattern that is common among the twelve prophets, Amos concluded his teachings with a message of hope. He beheld the flourishing of gathered Israel in the last days and prophesied:

“In that day will I raise up the tabernacle of David that is fallen . . . and I will raise up his ruins, and I will build it as in the days of old. . . .

“Behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that the plowman shall overtake the reaper, and the treader of grapes him that soweth seed” (Amos 9:11, 13).

These promises remind the reader that while God’s judgments against the wicked are harsh, the gate of repentance is ever open.[10]

We, like ancient Israel, are surrounded by the wickedness of the world. If we embrace wickedness, as Israel did in the eighth century BC, we may expect to see the consequences of justice. However, if we learn the lessons of Amos, maintain loyalties to our God, and care for the downtrodden, we may hope for the perpetual harvest and generous prosperity He promised.

Hosea

Hosea is a contemporary of Amos. Given Israel’s condition one might reasonably expect an additional witness of justice and doom to match that of Amos. Instead, Hosea encourages healing and reconciliation. The way Hosea encourages Israel to be reconciled with her God constitutes one of the most poignant and, for some, troubling episodes in the Old Testament—the Lord’s command for Hosea to marry a wife of whoredoms (see Hosea 1:2; 3:1). Hosea complied to this command by marrying Gomer, the daughter of Diblaim.

Regarding Hosea’s union to Gomer, it seems apparent that Hosea knew before their marriage of her tendencies toward harlotry (see Hosea 1:2; 3:1). In this light, the following scenario seems likely: at some point prior to her marriage to Hosea, Gomer had embraced the wickedness so prevalent in Israel at the time; later, she forsook her sins and married Hosea; then, tragically, she returned to wickedness, committed adultery, and broke Hosea’s heart.[11] This marriage is then likened to Israel’s relationship to Jehovah. The principal lesson to be learned from this parallel is that, in the Lord’s eyes, idolatry is adultery. Therefore, unlike Amos, who describes Israel’s wickedness from the prosecutor’s perspective, Hosea is uniquely qualified to describe Israel’s offenses from the touching and tender viewpoint of Jehovah as a victim who has been jolted by infidelity but still lovingly yearns for the return of His bride.

These yearnings provide the context for language rich in tones of love and intimacy. These messages constitute the major teachings of Hosea. For example:

“I taught Ephraim also to [walk], taking them by their arms;

“. . . And I was to them as they that take off the yoke on their jaws, and I laid meat unto them.

“. . . How shall I give thee up, Ephraim? how shall I deliver thee, Israel? . . .

“I will not execute the fierceness of mine anger, I will not return to destroy Ephraim: for I am God, and not man. . . .

“They shall walk after the Lord: he shall roar like a lion . . . and I will place them in their houses, saith the Lord” (Hosea 11:3–4, 8–11).

These verses describe Jehovah as a parent, master, loyal companion, and guardian. First, He is like a loving parent of Israel who, bent over and anxious, holds on to the arms of His toddler to teach her to walk. Second, Jehovah is a gentle master showing deep concern for His prized animal by carefully removing the bit from her mouth and feeding her life-sustaining meat. He is also a loyal companion who will do for Israel what mortals frequently will not do on the heels of adultery—take back His errant, backsliding, and rebellious spouse. Finally, Jehovah is a roaring lion. In stark contrast to the imagery employed by Amos, Hosea’s lion defends the returning prodigal and escorts her to a haven of safety. Without question, Hosea depicts the depth of love and devotion that God maintains for His children under all circumstances.

In the last days, the world is fraught with idolatrous temptations that tug at our loyalties. From Hosea we learn the need for absolute spiritual fidelity. God makes it clear that any tampering with the false gods of our modern world is deeply troubling to Him and should be stopped immediately. For any who have succumbed to such influences, Hosea’s message is also clear: Jehovah shows mercy when we meekly return to Him and worship God in truth.

Jonah

Jonah was a court prophet from Gath-hepher, a small village north of Nazareth in Galilee. He apparently had a local mission to the court of Jeroboam II in Samaria, as noted in 2 Kings 14:25, but the Lord had other plans for Jonah. The Lord said, “Arise, go to Nineveh, that great city, and cry against it; for their wickedness is come up before me” (Jonah 1:2). Instead of traveling northeast toward the Assyrian capital, he fled in the opposite direction to escape contact with the hated Assyrians. As with most Israelites in the eighth century BC, Jonah evidently held deep and bitter feelings against Israel’s enemy. As will be seen, his troubling experiences and miraculous deliveries serve as a type or shadow of God’s dealings with the entire house of Israel.

Assyrians were infamous for their barbarous methods of conquest and their treatment of captured enemies. They were known to force captives to parade through the streets of Nineveh with other captives’ decapitated heads around their necks. The Assyrians were masters of torture, cutting off noses and ears and yanking out tongues of live enemies. They flayed prisoners and skinned them alive or, as depicted on the Lachish siege panels from Sennacherib’s palace at Nineveh, they rammed sharpened poles up through their captives’ mid-sections, mounted them vertically, and left them to die.[12] In light of these atrocities, Jonah’s response to the Lord’s call could be summarized as follows: “I’ll go where you want me to go, dear Lord, except Nineveh!”

Despite Jonah’s rebellious flight, the Lord mercifully orchestrated his delivery to Nineveh in the belly of a great fish and gave him a second chance to fulfill his mission. Unfortunately, when the people of Nineveh hearkened to his preaching, repented, and avoided destruction, Jonah could not let go of his hatred of Assyrians. He would rather die than see an Assyrian saved (see Jonah 4:1–3). He went to the eastern edge of the city, built a booth, sat under it, and waited in hopes that God would still destroy the repentant inhabitants of Nineveh.

At this juncture, the Lord could have justifiably smitten Jonah for his lack of compassion. Instead, He extended another measure of mercy to Jonah in an effort to teach him a lesson. He raised up a gourd under which Jonah could find additional relief from the heat. This gourd made him extremely glad. The next day the Lord killed the gourd, and Jonah became angry. God also raised the temperature by sending a sweltering east wind to beat upon him.

In this state of discomfort and disgust, Jonah asked the Lord for the second time to end his life. The Lord then said:

“Thou hast had pity on the gourd, for the which thou hast not laboured, neither madest it grow; which came up in a night, and perished in a night:

“And should not I spare Nineveh, that great city, wherein are more than six-score thousand persons that cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand; and also much cattle?” (Jonah 4:10–11).

By recording this question, Jonah teaches his contemporaries and latter-day readers that the worth of souls is great in the sight of God (see D&C 18:10, 15–16). Jonah had underestimated the love and mercy that God has for all His children. This point is accentuated by the Lord’s proclaiming that He not only wants to save the people of Nineveh, He also wants to save their cattle! In other words, the spiritual and temporal welfare of all God’s creations matter.

Considering how the Lord often teaches us through types and symbols, Jonah represents, in a sense, the whole Israelite people, who were trying to flee from their appointed mission.[13] As Jonah was swallowed by a great fish, so Israel would be swallowed by disaster and exile, but some would then be brought back and allowed once again to be tried and proved in fulfilling their role as a covenant people.

From time to time, Latter-day Saints are mocked, scorned, and made “a hiss and a byword” (1 Nephi 19:14). At these moments, it may be tempting to look upon those we suppose to be our enemies and despise them so that we remove any desire in our hearts that God save them. At such times, we should learn from Jonah’s poignant experiences and leave such things in the hands of God.

Micah

Micah was a Morasthite (see Micah 1:1), one who came from Moresheth-gath, about twenty miles southwest of Jerusalem, near the border between Judah and Philistia. His ministry was during the reigns of Jotham (742–735 BC), Ahaz (735–715 BC), and especially Hezekiah (715–687 BC), all kings of Judah (see Jeremiah 26:18). Micah was a contemporary of the prophets Isaiah, Amos, Hosea, and Jonah. All of their ministries were fraught with similar spiritual, social, and political struggles, and their messages necessarily addressed similar ills in the Israelite kingdoms. Micah’s call was specifically to the capital cities of Samaria (Israel) and Jerusalem (Judah). He prophesied the captivity of Samaria in the north and Judah in the south, their ultimate restoration to the land, and the coming of the Messiah.

As we have seen, Israel and her capital city Samaria were guilty of gross idolatry. Micah is quick to point out that Judah, like Israel, had stooped to “the hire of an harlot” by forsaking her covenant relationship with Jehovah and worshiping false gods (Micah 1:7). Like Israel, Judah indulged in blatant greed. The poor were robbed, and even women and children were commonly plundered, exploited, and left homeless to appease the growing appetite for accumulated wealth among Judahites (see Micah 2:2, 9). This corruption infected every level of society, leading Micah to proclaim: “The good man is perished out of the earth. . . . The best of them is as a brier” (Micah 7:2, 4). Finally, as with Israel, Judah was guilty of hollow and impersonal worship of Jehovah. Like Amos and Hosea, Micah teaches that ritual without righteous intent is repugnant to the Lord. “Will the Lord be pleased with thousands of rams, or with ten thousands of rivers of oil? . . . He hath shewed thee, O man, what is good; and what doth the Lord require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?” (Micah 6:7–8). As a result of these maladies, Micah foretold the destruction of Jerusalem which, like Samaria, would “be plowed as a field” and become heaps (Micah 3:12).

With the image of rampant corruption and the capital cities smoldering in the dust of their own destruction, Micah follows the prophetic pattern of providing a message of hope to the inhabitants of Israel and Judah (see Micah 4:1). His message is simple: at all cost, Israelites must maintain a clear focus on Jehovah and true worship in His temple.

Concerning Jehovah, Micah prophesied of a coming day when the Messiah would condescend and be born in Bethlehem (see Micah 5:2). The remainder of Micah 5 is full of blessings promised to Israelites who will focus their lives on Him. These will “stand and feed in the strength of the Lord” (Micah 5:4); they will enjoy peace and be delivered from their enemies (Micah 5:5–6, 9); they will be like nourishing dew and life-saving rain to the rest of the world (see Micah 5:7); they will enjoy the collective awe of the Gentiles “as a lion among the beasts of the forest” (Micah 5:8); and they will not be caught in the snares of idolatry as their forebears so frequently were (see Micah 5:12–13). Concerning the temple, Micah taught that:

“The mountain of the house of the Lord shall be established in the top of the mountains . . . and people shall flow unto it.

“And many nations shall come, and say, Come, and let us go up to the mountain of the Lord . . . and he will teach us of his ways, and we will walk in his paths: for the law shall go forth of Zion, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem” (Micah 4:1–2).

Micah’s teachings are equally applicable in our day. If Latter-day Saints will maintain a clear focus on the Savior and the temple, they will receive three blessings: first, they will be taught the truth; second, they will receive strength to walk in God’s prescribed path as outlined in the temple; and third, they will be governed by the Lord in all they do. If Latter-day Saints follow this course, it is unlikely that they will repeat the mistakes of ancient Israel and Judah.

From Hezekiah to Josiah: Zephaniah and the Turbulent Seventh Century BC

As alluded to earlier, the northern kingdom of Israel was destroyed in 721 BC by Assyria. Many Israelites were killed at this time, many others were scattered throughout Assyrian provinces, and many were left in the lands around Samaria where they intermingled with Assyrian citizens who were moved to the region to ensure, as much as possible, a stable and loyal population (a political ploy often called “transpopulation”). More than a hundred years later, the southern kingdom of Judah suffered a similar fate at the hands of the Babylonians.

The final century of Judah’s existence was fraught with upheaval (see 2 Kings 21–25; 2 Chronicles 33–36). King Hezekiah of Judah (715–687 BC) rebelled against the overwhelming power of Sennacherib, king of Assyria, during the ministries of Isaiah and Micah. The result was that the forces of Sennacherib pummeled every major stronghold of Judah except one. With those victories behind him, Sennacherib turned his armies toward Jerusalem. With destruction seemingly imminent, Isaiah prophesied that Sennacherib would not even shoot an arrow in Jerusalem, let alone conquer her (see 2 Kings 19:6–7, 32–33). Hezekiah fortified the city and trusted in Isaiah’s assurance from the Lord. Isaiah’s prophecy was fulfilled when the Lord miraculously saved Jerusalem by destroying the approaching Assyrian army (see 2 Kings 19:35–37). In the end, Jerusalem was preserved, but Assyria maintained control over Judah. Hezekiah’s daring bid for independence had failed (see 2 Kings 18–20).

While Assyria allowed Hezekiah to retain his throne, he died shortly thereafter and his young son Manasseh became king of Judah (see 2 Kings 21).[14] During Manasseh’s reign (ca. 687–642 BC),[15] Assyria reached her peak of power.[16] Manasseh had no choice but to wholly submit to vassalage. Even so, he could have maintained Hezekiah’s religious reforms and reverential awe for Jehovah. Unfortunately, in this regard, Manasseh’s kingship was radically different from that of his father. Manasseh was evil and murderous, and he reinstituted idolatry on a scale never before seen in Judah.

For he built up again the high places which Hezekiah . . . had destroyed; and he reared up altars for Baal, and made a grove, as did Ahab king of Israel; and worshipped all the host of heaven. . . . He built altars in the house of the Lord. . . . He built altars for all the host of heaven in the two courts of the house of the Lord. And he made his son to pass through the fire [human sacrifice], and observed times, and used enchantments, and dealt with familiar spirits and wizards. . . . Moreover Manasseh shed innocent blood very much [possibly those who protested his idolatrous policies], till he had filled Jerusalem from one end to another. (2 Kings 21:3–6, 16)

Finally, the author of Kings marks Manasseh as the man who “seduced [Judah] to do more evil than did the nations whom the Lord destroyed before the children of Israel” (2 Kings 21:9; see also Leviticus 18).For almost half a century, Manasseh’s wickedness shaped the milieu in Judah. The worship of Jehovah was merged so completely with idolatry that it was barely distinguishable from paganism. It was a spiritual crisis of enormous proportions. The Lord’s wrath was kindled, and He sent prophets to testify against this rapid spiritual devolution. While we do not have all of their names, these prophets boldly prophesied of imminent destruction: “I will wipe Jerusalem as a man wipeth a dish, wiping it, and turning it upside down” (2 Kings 21:13).

Conditions did not improve after the death of Manasseh in 642 BC. His son, Amon, assumed the throne and immersed Judah in more of his father’s wickedness. He was assassinated by conspirators after two years in power. Amon’s murderers were smoked out and executed while Josiah, Manasseh’s grandson and Amon’s son, became king (2 Kings 21:17–22:1). Judah was on the brink of internal destruction. Josiah seems destined to have come to power “for such a time as this” (Esther 4:14).

Josiah (640–609 BC) “did that which was right in the sight of the Lord, and walked in all the way of David his father, and turned not aside to the right hand or to the left” (2 Kings 22:2). From 640–622 BC he initiated much needed reforms intended to refocus Judah on Jehovah. As will be seen later, these reforms were accelerated between 622 BC and Josiah’s death in 609 BC. However, sometime during the earlier period of Josiah’s reign, the Lord raised up Zephaniah, whose teachings girded up Josiah’s initial reforms and challenged Judah to shun idolatry and worship Jehovah in truth and purity or suffer severe repercussions.[17]

Zephaniah

Zephaniah’s ministry is characterized by expediency. Manasseh and Amon planted seeds of apostasy that Zephaniah saw grow to full corruption. Not surprisingly, much of the field is worthy only of burning. Like Noah before the Flood and like latter-day prophets before the Second Coming, Zephaniah commands his people to repent post-haste or expect dire consequences.[18] The prophet identifies how Judah has allowed herself to be overwhelmed by worldliness. For example, her people have turned their backs on God (see Zephaniah 1:6); they have embraced the strange clothing styles that fail to reflect the appearance of a covenant people (see Zephaniah 1:8); they lust after worldly wealth and acquire riches through corruption and plunder (see Zephaniah 1:9); and they are spiritually complacent (see Zephaniah 1:12).

Zephaniah also pronounces doom on the unbelieving nations to the north, south, east, and west of Judah. By bundling Judah together with these heathen peoples, Zephaniah suggests that God’s covenant people equal and surpass the wickedness of their neighbors (see Zephaniah 2:4–13). His final proclamation against Judah is that she is polluted, oppressive, unteachable, disobedient, and guilty of wresting the Torah (see Zephaniah 3:1–4). In response to wholesale wickedness, Zephaniah declares that “all the earth shall be devoured with the fire of [God’s] jealousy” (Zephaniah 3:8).

In the wake of this revelation of destruction, Zephaniah employs the phrases “in that day” and “at that time” to dually describe Judah (if they will repent) and covenant people in the latter days who remain unsullied by the influences of the world and witness the Second Coming of the Lord with its accompanying destruction of the wicked. Both are promised the presence of the Lord (see Zephaniah 3:3); an ability to worship God with a pure language (3:9); nontainted temple worship (3:11); trust (3:12); truth (3:13); nourishment (3:13); protection (3:15); and joy, rest, and love (3:17).

In a striking way, Zephaniah displays the fruits of evil and the fruits of righteousness. In three chapters he clearly depicts Judah’s choice in the seventh century BC and, at the same time, our choice in the latter days. If we turn to the Lord, His promises are sure. He will “make you a name and a praise among all people of the earth, when I turn back your captivity before your eyes, saith the Lord” (Zephaniah 3:20).

The Fall of Assyria: Nahum’s Condemnation of Nineveh

As previously mentioned, the prowess of Assyria peaked during the reign of Manasseh. They controlled the regions from Babylonia to Asia Minor, south through Israel and encompassed Egypt (see Bible Map 5). As it was with Jonah and Israel, the lion’s share of these vassal kingdoms deeply hated Assyria, in part because of the vicious and violent means the Assyrians employed to maintain control in their sprawling empire.

Through the second half of the seventh century, uprisings against Assyria were common and became increasingly difficult for the empire to put down. Then, in 626 BC, the Babylonians, under the command of Nabopolassar (lived 626–605 BC and was the father of Nebuchadnezzar), defeated Assyrian forces outside Babylon and declared their independence. Despite vigorous efforts to strike down this rebellion, Assyria never removed Nabopolassar.[19] His success encouraged one rebellion after another, and the vastness of the empire made it next to impossible to control. The Assyrian empire began to unravel and eventually collapsed under its own weight. These events loosened Assyria’s grip on Judah, making it possible for Josiah to institute even greater reforms beginning in 622 BC.

Ultimately, the Medes joined the Babylonians and destroyed Asshur (Assyria’s ancient capital) in 614 BC. Two years later they laid siege to Nineveh (the then-current capital) for three months, after which they entered the city and razed it to the ground. By 610 BC Assyria had vanished as a nation and Babylon (Chaldea) rose as the preeminent force in the region.[20] Late in the seventh century BC, perhaps shortly before the collapse of Assyria, Nahum prophesied of the destruction of Nineveh and the greater Assyrian Empire.

Nahum

The book of Nahum may not seem very inspirational or uplifting. Its tone is accusatory and vengeful, seemingly bereft of ethical and theological empathy. Nahum’s words almost burn with anxiety to see judgments poured out on the barbarous Assyrians. Nevertheless, Nahum was called to pronounce the Lord’s condemnation on the Ninevites. Nahum testified that though the Israelite nation was militarily feeble and unthreatening, the God of Israel was still God of all the earth, and He was about to unleash His fury and vengeance on His adversaries. In Nahum’s words: “God is jealous, and the Lord revengeth . . . and is furious; the Lord will take vengeance on his adversaries, and he reserveth wrath for his enemies” (Nahum 1:2). Nahum’s description of Nineveh provides insight into how deeply Assyria had offended the Lord. He notes:

“She is empty, and void, and waste. . . .

“Woe to the bloody city! it is all full of lies and robbery. . . .

“Behold, I am against thee, . . . and I will shew the nations thy nakedness, and the kingdoms thy shame.

“And I will cast abominable filth upon thee, and make thee vile, and will set thee as a gazingstock. . . .

“There is no healing of thy bruise; thy wound is grievous: all that hear the [report] of thee shall clap the hands over thee: for upon whom hath not thy wickedness passed continually?” (Nahum 2:10; 3:1, 5– 6, 19).

Nahum proceeds to break the usual pattern of doom followed by hope. For Nineveh, there was no hope. Rather, Nahum invites Judah to rejoice in the destruction of Assyria and claim the opportunity to cleanse the temple and worship God freely through prescribed feasts and vows. “Behold upon the mountains the feet of him that bringeth good tidings, that publisheth peace! O Judah, keep thy solemn feasts, perform thy vows: for the wicked shall no more pass through thee; he is utterly cut off” (Nahum 1:15). Unlike Israel, Nineveh would never enjoy a restoration. Decade after decade, Nineveh was terminally pompous, immersed in worldly power, witchcraft, whoredoms, and the supposed merits of materialism (see Nahum 3:4, 16–17).

Under these conditions, God ruled that Nineveh had to be destroyed. And in her destruction Nineveh stands as a symbol of the hopeless condition of the wicked at the time of the Second Coming (see Nahum chapter 1 heading). In this light, the message of Nahum revolves around the question “Who can stand in the presence of the Lord?” The book of Nahum is a hard message to Nineveh but also to people living in the last days who fail to trust in God. Without repentance, their fate is as sure as that of Nineveh. “Who can stand before his indignation? . . . His fury is poured out like fire, and the rocks are thrown down by him. The Lord is good, a strong hold in the day of trouble; and he knoweth them that trust in him. But with an overrunning flood he will make an utter end. . . . And while they are drunken as drunkards, they shall be devoured as stubble fully dry” (Nahum 1:6–8, 10).

The Rise of Babylon and Destruction of Jerusalem: Habakkuk and Obadiah

We have already mentioned the initial reforms of King Josiah sometime after 640 BC (see 2 Kings 22–23). These reforms gained momentum rapidly when, during renovation work in the temple in 622 BC, Hilkiah (the high priest) discovered “the book of the law” (2 Kings 22:8). The book, which is commonly held to be some form of the book of Deuteronomy,[21] provided an overview of the covenant nature of Israel’s relationship to God. It gave examples of how Jehovah honored His covenant with Israel even if miraculous intervention was necessary to do so. It also emphasized the absolute necessity of Israel’s loyalty to God through the covenant. Josiah was deeply moved by the contents of the book. He gathered his people to the temple (Jeremiah was most likely present, and possibly Lehi as well), read the book to them, and placed himself and all his followers under covenant to abide by the law found in the book and to honor their covenant relationship with Jehovah.

Unfortunately, Josiah was killed in battle by Egyptian forces led by Pharaoh Nechoh at Megiddo in 609 BC (see 2 Kings 23:29). Egypt annexed Israel into their domain in the wake of Assyria’s collapse, and four years later (605 BC), Babylon took Israel from Egypt. From Josiah’s death to the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BC, Judah had four kings: Jehoahaz (son of Josiah), Jehoiakim (son of Jehoahaz and first vassal of Babylon), Jehoiakin (son of Jehoiakim), and Zedekiah (brother of Jehoiakim and uncle of Jehoiakin). Without exception, each of these kings did evil in the sight of the Lord. Josiah’s reforms, the most sweeping in Judah’s history, were thoroughly overturned, and idolatry in all its forms was reinstituted throughout the land. Like her sister-state Israel, who just over a century earlier had mocked the Lord and was scattered, so Judah was on the brink of outright destruction at the hands of the Babylonians (also known as the Chaldeans) and her vassals such as Edom. These were the desperate days of the ministries of Habakkuk and, after Judah’s destruction, Obadiah.

Habakkuk

Habakkuk prophesied against Babylon in the same way that Isaiah prophesied against Assyria (see Isaiah 10).[22] Babylon would be used as God’s arm to crush Judah. Then, like Assyria, Babylon would be destroyed for their idolatry, their trust in munitions, and their total disregard for social justice and human life. Even with Assyria as a precedent, Habakkuk is dismayed that the Lord would use such a vile and pagan nation to destroy God’s own people. In a prayer similar to Joseph Smith’s later plea, Habakkuk asks:

“O Lord, how long shall I cry, and thou wilt not hear! even cry out unto thee of violence, and thou wilt not save! . . .

“Therefore the law is slacked. . . . The wicked doth compass about the righteous; therefore wrong judgment proceedeth” (Habakkuk 1:2, 4; compare D&C 121:2).

In response, the Lord explained to the prophet that while Judah will suffer destruction at the hands of a bitter, hasty, terrible, and dreadful nation (see Habakkuk 1:6–7), Babylon will also fall. Babylon is guilty of at least two things: first, dealing treacherously with mankind (especially the righteous); and second, imputing power to their idolatrous gods (see Habakkuk 1:1–17).

To the first charge, the Lord explains:

“Woe to him that buildeth a town with blood, and stablisheth a city by iniquity! . . .

“Woe unto him that giveth his neighbour drink, that puttest thy bottle to him, and makest him drunken also, that thou mayest look on their nakedness!

“Thou art filled with shame for glory. . . . The cup of the Lord’s right hand shall be turned unto thee, and shameful spewing shall be on thy glory” (Habakkuk 2:12, 15–16).

To the charge of idolatry, the Lord admonishes:

“Woe unto him that saith to the wood, Awake; to the dumb stone, Arise, it shall teach! Behold, it is laid over with gold and silver, and there is no breath at all in the midst of it.

“But the Lord is in his holy temple: let all the earth keep silence before him” (Habakkuk 2:19–20).

Taken together, the central message of Habakkuk is that God is in charge. Chapter 3 is a poetic song written to celebrate God’s majesty and dominion over all the forces of earth and hell. Everything in the telestial world is prone to collapse except the Lord (see Habakkuk 3:17). The phrase “the Lord is in his holy temple: let all the earth keep silence before him” is another way of saying, “Be still; I’m aware of your concerns; know that I am God.” The essential characteristic of those who survived spiritually in Habakkuk’s day and our own is captured in Habakkuk 2:4, which says, “The just shall live by his faith.” To these the Lord promises joy, strength, and the richness of walking in the high places of the Lord (see Habakkuk 3:18–19).

Obadiah

Obadiah prophesied sometime after the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem and the exile of the Jews to Babylon. He proclaimed a message of doom to Edom (Esau’s ancient land of inheritance and oft-time enemy of Israel). Obadiah’s accusation against Edom was threefold: first, they were guilty of deep-seated pride and arrogance (see Obadiah 1:3–4). Second, as the Babylonians ransacked Jerusalem and burnt the temple, Edom “wast as one of them” (Obadiah 1:11) and “rejoiced over the children of Judah in the day of their destruction” (Obadiah 1:12). Third, Edomites colluded with the Babylonians by blocking mountain passes through which Jews fled to escape the destruction of the city. Those fleeing were caught by Edomites and turned over to Babylonian forces (see Obadiah 1:14). These three crimes would lead to their ultimate destruction.

Beginning in verse 15, however, the prophet makes a sudden transition from immediate to ultimate things to tell us what shall happen to the wicked in the last days. “As thou hast done, it shall be done unto thee: thy reward shall return upon thine own head” (Obadiah 1:15). During this latter-day destruction of the wicked, there will be one special place of refuge: the temple (see Obadiah 1:17). Obadiah prophesied of a day when all in the world, who are willing, may gather together with latter-day Israelites. Descendants of Jacob (Israel) and Joseph will present a standard to the world that is likened to a fire and a flame. This fire of the gospel will give light to those who seek it and burn up the wicked, latter-day “Edomites” as if they were stubble (see Obadiah 1:18; see also D&C 1:36).

With the Lord’s destruction of the wicked comes a new order wherein all things of import revolve around the Lord’s temple. “And saviours shall come up on mount Zion, . . . and the kingdom shall be the Lord’s” (Obadiah 1:21). Joseph Smith interpreted this verse: “But how are they to become saviors on Mount Zion? By building their temples, erecting their baptismal fonts, and going forth and receiving all the ordinances, baptisms, confirmations, washings, anointings, ordinations and sealing powers upon their heads, in behalf of all their progenitors who are dead, and redeem them that they may come forth in the first resurrection and be exalted.”[23]

The clear message of Obadiah to us in the latter days is to avoid pride, not to rejoice in wickedness even from a distance, and finally, to refuse to follow the evil influences of the world. Our best course should include a focus on the mountain of the Lord. If the temple becomes our central ideal, we may stand above the sordid elements of the world and wave a flaming ensign for all to see and gather to on both sides of the veil. In this way we become the saviors that Obadiah saw over two millennia ago.

The Exile of the Jews and Their Restoration[24]

The destruction of the temple in Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar’s armies in 586 BC, in concert with the exile of the Jews to Babylonia, should have marked the end of the Jewish nation. Miraculously it did not. The Babylonians deported the brightest cadre of spiritual, civic, and intellectual leaders, along with their families, from Judah to Babylon. Jeremiah records that those exiled numbered four thousand six hundred—a count probably limited to men only (see Jeremiah 52:28–30). While this group may seem large, many were left behind in Judah as a broken, leaderless people, forced to eke out a living and pay tribute from the fruits of an overrun land.

It is evident from the book of Ezekiel that the Jews in Babylon fared much better than the ten tribes. The Jews were kept in a unit and were not scattered, as were the ten tribes, who were taken into various places of captivity by the Assyrians. Both Daniel and Ezekiel functioned as prophets in captivity—Ezekiel among the people and Daniel in the royal court—but very little is told about their personal lives there. Jeremiah predicted that the Babylonian captivity would last seventy years (see Jeremiah 25:8–11; Daniel 9:2). Indeed, it did not take long for Babylonian power to begin to collapse, giving some exiles hope of an eventual return to Jerusalem.

Babylon’s greatest rival was the Medes to the northeast. While the two had been allies against Assyria, Media now waited for an opportunity to increase their borders at Babylon’s expense. An uprising within Media led by a vassal king named Cyrus of Persia (east of Babylon) was likely a welcomed disruption. A brilliant military leader, Cyrus went on to overtake the entire Median empire by 550 BC. Given the size and military might of the new Persian empire, Babylon posed little threat. After enlarging Persian interests to the east, the forces of Cyrus eventually turned their attention to Babylon, taking her without a fight in 539 BC.

The policies of Cyrus toward peoples he conquered were markedly different from those of the Babylonians and the Assyrians. He instituted a policy of respect for the religious and cultural beliefs and practices of those living within his realm. In the first year of his reign over Babylon, Cyrus issued a royal decree ordering the restoration of the exiled Jews to Jerusalem. He also commissioned the reconstruction of the temple in Jerusalem to facilitate the worship of Jehovah (see Ezra 1). Finally, Cyrus appointed “Sheshbazzar, the prince of Judah” (Ezra 1:8; presumably the same man of the kingly line that is called Shenazzar in 1 Chronicles 3:18, the son of King Jehoiachin) to lead the first group of exiles back to Jerusalem to begin rebuilding the temple.

It is likely that only the hardiest Jews and those most committed to rebuilding the temple traveled back to Jerusalem with Sheshbazzar in this initial group. Apparently, many Jews were by then very comfortable in Babylon and offered their resources to assist others but were not interested in returning themselves. Josephus reported that “the rulers of the two tribes of Judah and Benjamin, with the Levites and priests, went in haste to Jerusalem, yet did many of them stay at Babylon, as not willing to leave their possessions.”[25]

Upon their arrival in Jerusalem, they found the mere shell of a city. Nevertheless, the small band began at once to rebuild the temple (see Ezra 5:16). Progress was slow, however, as a series of setbacks such as crop failures, drought, and the onset of extreme poverty hindered their efforts (see Haggai 1). It was during these early days that Sheshbazzar’s nephew, Zerubbabel, arrived in Jerusalem at the head of another group of returning exiles. He became the governor of Judah presumably at the death of his uncle and was the final Davidic descendant to govern in Judah. With him came lingering hopes of an eventual return to the ancient monarchy. As we shall see, these hopes would be extinguished at the death of Zerubbabel.

Furthermore, there were tensions between the inhabitants of the land and the returning exiles. The exiles looked upon the inhabitants as ritually unclean (see Haggai 2:12–14), and the exiles were looked upon as encroachers upon land that was no longer theirs (see Ezekiel 33:24). Finally, political developments played a role in delayed temple construction. Cyrus died and was replaced by his son Cambyses (530–522 BC), and as the years passed the edict of Cyrus was eventually forgotten altogether (see Ezra 5:17–6:1). At the death of Cambyses, Darius (son of Hystaspes) took the throne and was securely in power by 520 BC. A decade and a half had passed, and work on the temple had not progressed beyond laying the foundation stones. Simply, the weight of poverty, political disruption, animosities, and a backbreaking need to survive brought the construction to a halt with no new beginning in sight. It was under these circumstances that the Lord raised up Haggai and Zechariah to spur on his beleaguered people. It is likely that Joel also prophesied at this time. In the final analysis, these prophets were successful. The second temple was completed in 515 BC, and against all odds, Israel survived as a distinct people.

Haggai

After nearly two decades of living near the destroyed temple complex, it apparently grew easier and easier for the returned exiles to be satisfied that, while there was no temple, they did enjoy daily sacrifice at the altar they had rebuilt (see Ezra 3:2–3). No doubt it took an immense amount of labor in the early days of their return just to clear rubble from the site to make these daily sacrifices possible. By the time of Haggai’s ministry in 520 BC the common sentiment of the Jews was that “the time is not come, the time that the Lord’s house should be built” (Haggai 1:2).

Haggai’s message from the Lord was just the opposite: “Consider your ways. Go up to the mountain, and bring wood, and build the house; and I will take pleasure in it, and I will be glorified, saith the Lord” (Haggai 1:7–8). Haggai went on to explain that Judah had not prospered and would not prosper until the Jews paid strict heed to their obligation to build the temple:

“Ye looked for much, and, lo, it came to little; and when ye brought it home, I did blow upon it. Why? saith the Lord of hosts. Because of mine house that is waste, and ye run every man unto his own house.

“Therefore the heaven over you is stayed from dew, and the earth is stayed from her fruit” (Haggai 1:9–10).

Haggai likened the returning exiles to ancient Israelites being led out of bondage from Egypt and prophesied similar deliverance as they worked to build the second temple and keep themselves separate from the pagan influences prominent among the long-term inhabitants of the land. The Lord promised through Haggai that “according to the word that I covenanted with you when you came out of Egypt, so my spirit remaineth among you: fear ye not” (Haggai 2:5).

As the Second Coming approaches, we, like the exiles of Haggai’s day, must gather, build temples, and live worthily to enter therein. For more than fifteen years, the Jews justified their inattention to the Lord’s will that they construct the temple. The result was predictable—they did not prosper. So it is today: if we fail to heed the revelations of our time we will be guilty of “a very grievous sin” and will be the recipients of sore chastisement from the Lord (D&C 95:3). However, if we do follow the direction of our prophets and focus on the temple, we will find that the peace and glory of this “latter house” shall be great (Haggai 2:9).

Zechariah

Zechariah’s revelation came about two months after Haggai’s (see Haggai 1:1 and Zechariah 1:1). A prominent theme in the book of Zechariah is the exploration of God’s feelings for the city of Jerusalem and her inhabitants in Zechariah’s day, in the meridian of time, and in the latter days. Many of Zechariah’s prophecies and doctrinal teachings are couched in this theme.

When Jerusalem was destroyed, Judah’s supposition that Jehovah would protect Jerusalem under all circumstances was shattered. The city lay in rubble. Without the temple and the faithful followers of Jehovah, Jerusalem was on the verge of being no different than any other pagan city in the region. The returning exiles needed to redefine their faith. Part of Zechariah’s message was that only a holy people could make Jerusalem holy again. Therefore, Zechariah invited the people to submit to Jehovah’s rule and to follow Joshua, the high priest, as he sloughs off the filth of the world, walks in the ways of the Lord, dons clean clothing, is crowned with a fair mitre, and walks among the angels of the Lord. Miraculously, such a change can transpire “in one day,” given the mighty power of Jehovah to cleanse and save (see Zechariah 3:1–7, 9).

Concerning Jerusalem in Zechariah’s day, the Lord proclaimed, “I am returned to Jerusalem with mercies: my house shall be built in it, saith the Lord of hosts” (Zechariah 1:16). In addition to this, Zechariah’s depiction of Jerusalem in the last days is stunning:

“Jerusalem shall be inhabited as towns without walls for the multitude of men and cattle therein:

“For I, saith the Lord, will be unto her a wall of fire round about, and will be the glory in the midst of her. . . .

“And the Lord shall inherit Judah his portion in the holy land, and shall choose Jerusalem again” (Zechariah 2:4–5, 12).

Both of these declarations would have supplied much needed encouragement to the downtrodden exiles working to rebuild the temple.

Zechariah made it clear that Jerusalem will play a key role in the ongoing ministry of the Messiah. He prophesied of the Savior’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem prior to His atoning sacrifice (see Zechariah 9:9), His betrayal (see Zechariah 11:12), as well as His triumphant appearance to the Jews on the Mount of Olives at His Second Coming (see Zechariah 12:10; 14:4). He also prophesied that Jerusalem will one day be a city of peace from which the Lord will govern. In that day, Jerusalem will be called a city of truth where children will play safely in the streets and grow to old age without war and turmoil. Simply, the prophecies of Zechariah give hope to the faithful in at least three time periods: to his contemporaries struggling to rebuild the temple in 520 BC, to the faithful in the meridian of time who were waiting for the Messiah to come, and to the Saints in the last days who are looking forward to the Second Coming of the Savior.

All three time periods share at least one piece of common ground in the writings of Zechariah. Faithful people, not buildings, make a place holy (see Zechariah 8:23). This is a timely message for Latter-day Saints. At a time when a new chapel is completed every day, multiple temples are built and dedicated each year, and grand buildings like the Conference Center mark the skyline of the Church headquarters complex, it may be tempting to think that our buildings mark our faith. While beautiful buildings are important to our worship, the only accurate indicator of our spiritual condition is the nature of our hearts.[26] According to Zechariah, if our hearts are centered in God, we will triumph with Him and God will be to us “a wall of fire round about” that no wickedness can penetrate (Zechariah 2:5).

Joel [27]

The dominant theme of the prophecy of Joel is “the day of the Lord” (Joel 1:15; see also 2:1, 11, 31; 3:14, 18). This phrase always refers to the Second Coming. The latter days are clearly the focus of his prophecy. In this light, Joel serves as an instruction manual for our time. His counsel could be summarized in two phrases: “turn to me” and “gather to the temple and pray.”

The destruction described by Joel is so horrific and all-encompassing that those without refuge will perish. The destruction is brought on, in part, because the people of the earth have abandoned their God. Superficial rites replace true worship rooted deep in the heart. The result of such behavior “in the day of the Lord” is the same as it was in the days of Amos, Hosea, or Zephaniah—God humbles the disobedient with the awe-inspiring forces at His disposal.

Joel describes his vision of wasted fields, rotten seed, broken and empty barns, starving animals, and the weak and broken inhabitants of the land on the verge of complete destruction. They are pursued by a disciplined and terribly ferocious army. On all sides, the people in Joel’s vision are consumed. “A fire devoureth before them; and behind them a flame burneth: the land is as the garden of Eden before them, and behind them a desolate wilderness; yea and nothing shall escape them” (Joel 2:3). At this moment of greatest alarm, the Lord provides the only solution when He commands:

“Therefore also now, saith the Lord, turn ye even to me with all your heart, and with fasting, and with weeping, and with mourning:

“And rend your heart, and not your garments, and turn unto the Lord your God: for he is gracious and merciful, slow to anger, and of great kindness” (Joel 2:12–13).

The second directive of Joel is to gather to the holy temple and pray for deliverance. Joel observed: “Sanctify ye a fast, call a solemn assembly, gather the elders and all the inhabitants of the land into the house of the Lord your God, and cry unto the Lord” (Joel 1:14). According to Joel, the temple is the only place of refuge from destruction in the day of the Lord. No interest or duty can safely be elevated above the temple. Consider the following:

“Gather the people, sanctify the congregation, assemble the elders, gather the children, and those that suck the breasts: let the bridegroom go forth of his chamber, and the bride out of her [wedding canopy].

“Let the priests, the ministers of the Lord, weep between the porch and the altar, and let them say, Spare thy people” (Joel 2:16–17).

If, on the day of the Lord, God’s people have turned to Him with all their hearts, have made the temple the focal point of their spiritual relationship with Him, and have become humble enough to cry out to the Lord for deliverance, they will receive great blessings. Joel prophesied that:

The Lord also shall roar out of Zion, and utter his voice from Jerusalem; and the heavens and the earth shall shake: but the Lord will be the hope of his people, and the strength of the children of Israel.

So shall ye know that I am the Lord your God dwelling in Zion, my holy mountain: then shall Jerusalem be holy, and there shall no strangers pass through her any more. . . .

But Judah shall dwell for ever, and Jerusalem from generation to generation.

For I will cleanse their blood that I have not cleansed: for the Lord dwelleth in Zion. (Joel 3:16–17, 20–21)

Simply put, for those who follow Joel’s counsel, the Second Coming of the Savior will not be terrible; rather, it will be great.

The Final Decades of Old Testament History

As a general rule, those living in and around Jerusalem in 520 BC were from one of two camps: first, returned exiles who hoped to rebuild the temple, restore the Davidic monarchy, and participate in true worship of Jehovah; or second, the native population who had not been taken away to Babylon seventy years earlier. This second group was thoroughly immersed in pagan practices, and their religion no longer resembled the pure truth of God.[28] Concerning the first group, very little is known about their dealings over the seventy years that separate Haggai (520 BC) and Malachi (ca. 450 BC). One thing is certain, however: there was a marked rise in power of the high priest and his associates at the temple. Since Israelite culture revolved around the temple, in every facet of life, the high priest and his associates, in large measure, secured the maintenance, or collapse, of pure religion during these years. This rise became pronounced at the death of Zerubbabel, who was the last known Davidic-line ruler in Judah. Upon his death, hope for the immediate restoration of the Davidic throne vanished, and priests filled the ensuant vacuum. They, in turn, were kept in check by prophets.[29]

Malachi

By 450 BC the priests and subsequently the people had corrupted the truth in almost every conceivable way. Malachi was charged by the Lord to correct the prevalent spiritual deviancy of Israel and invite the Israelites to return to the Lord. Without question, Malachi’s bold message provided encouragement and credibility to the reforms instituted by his contemporaries Nehemiah (the governor) and Ezra (the priest).

Considering that only seven decades or so had passed since the rebuilding of the temple, Malachi’s chronicle of wickedness is disheartening. He described Israel as having taken a wholesale turn to the half-baked religious practices so common among their forefathers. For example, the priests polluted the temple by offering blind, lame, and sick animals as sacrifices (see Malachi 1:8). Israelites withheld their male animals most suited for sacrifice and brought far less suitable livestock as offerings at the temple (see Malachi 1:14). The priests were guilty of corrupting the covenant by being partial in their application of the law—the result being that they caused “many to stumble” (Malachi 2:8). Furthermore, every man broke his covenants and dealt treacherously against his brother (see Malachi 2:10), marriages outside the covenant became commonplace, and the incidence of divorce soared (see Malachi 2:11–16). Finally, Israel was guilty of sorcery, adultery, false swearing, oppressing widows and the economically displaced, and robbing God of tithes and offerings (see Malachi 3:5–9). Sadly, Malachi’s description is remarkably similar to the assessment of Israel offered by Amos and Hosea three centuries earlier. As with Amos, Malachi warned of pending justice that could be avoided only by repentance. And like Hosea, Malachi extended a hand of hope to God’s undeserving yet covenant people. Malachi concluded his writings with a prophecy regarding the Second Coming. We will address Malachi’s messages regarding justice, mercy, and the Second Coming in turn.

The Lord’s voice of justice was unmistakable. He declared to Israel: “I have no pleasure in you” (Malachi 1:10), you are “cursed” (Malachi 1:14), “I will curse your blessings. . . . I will corrupt your seed” (Malachi 2:2–3), “I will be a swift witness against [you]” (Malachi 3:5). From these expressions, Malachi made it clear that God’s mercy cannot rob justice. Israel had a temple in her midst and a prophet to guide her in the right way. To continue abandoning true worship practices while embracing paganism and behaviors that were unbecoming a covenant people would not be tolerated. Once again, Israel was on the brink of destruction at the hand of God.

The Lord’s voice of mercy is also unmistakable in Malachi’s message. Importantly, this message is grounded in covenants between God and His followers: “Return unto me, and I will return unto you, saith the Lord of hosts” (Malachi 3:7). In their gross iniquity and filthiness, the Lord offered a much-needed cleansing through repentance. In this process Jehovah is “like a refiner’s fire, and like fullers’ soap” (Malachi 3:2), which purges iniquity and sin, making it possible for the “offering of Judah and Jerusalem [to] be pleasant unto the Lord, as in the days of old, and as in former years” (Malachi 3:4). Without question, Malachi promoted a return to covenants through true worship and sacrifice at the house of the Lord.

Furthermore, Malachi explained that the Israelites must manifest a reverential awe and respect toward God if they were to please Him. Their loyalties must be sure. If they were, the Lord promised, “But unto you that fear my name, shall the Son of righteousness arise with healing in his wings; and ye shall go forth and grow up as calves of the stall” (3 Nephi 25:2; compare Malachi 4:2). Speaking of those who possess this reverential awe, the Lord said, “And they shall be mine, saith the Lord of hosts, in that day when I make up my jewels; and I will spare them as a man spareth his own son that serveth him” (Malachi 3:17). Interestingly, the word jewels in this verse is a translation of the Hebrew segulla, which means “valued property or possession” or “royal treasure.” As justice cannot be averted for rebellious Israel, Malachi, like Hosea, makes a compelling case that God’s mercies were still sufficient for those willing to repent.

Finally, Malachi prophesied concerning the Second Coming of the Lord: “For, behold, the day cometh, that shall burn as an oven; and all the proud, yea, and all that do wickedly, shall be stubble: and the day that cometh shall burn them up, saith the Lord of Hosts, that it shall leave them neither root nor branch” (Malachi 4:1). The Lord singles out one particular sin—pride—and lumps all the rest of the sins of humanity into the generic “all that do wickedly.” It is obvious that the Lord hates pride (see Proverbs 6:16–17). He knows how that one sin is the basis for, and can lead to, so many other sins. Pride is the great distracter and obstructer to all spiritual progress. Those infected by pride will be burned as stubble at the Second Coming, being left with “neither root nor branch” (3 Nephi 25:1) This means that they will have in the eternal worlds neither ancestry nor posterity—no eternal family connections.

Before this day of burning, however, Malachi prophesied:

“Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the great and dreadful day of the Lord:

“And he shall turn the heart of the fathers to the children and the heart of the children to their fathers, lest I come and smite the earth with a curse” (Malachi 4:5–6).

This prophecy was fulfilled on April 3, 1836, when Elijah appeared to Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery in the Kirtland Temple (see D&C 110). On that day, Elijah bestowed the keys of the sealing power on the Prophet, making it possible in this dispensation, through temple ordinances, for the faithful to enjoy all the blessings of the priesthood promised to our fathers Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.[30] Malachi’s prophecy, then, is a call to God’s covenant people to avoid the calamities of the Second Coming by orienting their lives toward the holy temple and the eternal covenants and ordinances found therein. Receiving these covenants and ordinances will result in the receipt of the blessings promised to the ancient patriarchs. Rejecting them will result in a curse.

For Latter-day Saints, Malachi’s promises of mercy and justice are in place today, especially as they pertain to preparing for the Second Coming. If we ignore God’s commands, become prideful, and entwine ourselves in the things of the world, we should expect measures of His justice—even burning. However, if we submissively turn to the Lord and enter into eternal covenants with Him in the temple, we will be protected, nourished, and sheltered. Furthermore, He will make of us His most precious possessions.

Conclusion

While the Church continues to grow in size and, in many ways, faithfulness, we are not beyond the spiritual ills that are so consistently addressed by the twelve prophets of the Old Testament. Casual temple attendance, idolatry, materialism, taking advantage of the weak and downtrodden, and worship in form but not true intent continue, in varying degrees, today as they did anciently. Hence the value of the writings of these twelve prophets. To ignore them or skirt them as unimportant is shortsighted indeed. The Prophet Joseph Smith taught, “We never inquire at the hand of God for special revelation only in case of there being no previous revelation to suit the case.”[31] For so many of our nagging personal, familial, ecclesiastical, and cultural problems, the answers already lie within the pages of the Book of the Twelve. By studying the words of these prophets, we will increase our capability of keeping the covenants we have entered into with our God.

Notes

[1] The twelve prophets are Amos, Hosea, Jonah, Micah, Zephaniah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Obadiah, Haggai, Zechariah, Joel, and Malachi.

[2] Sirach 49:10.

[3] See Sidney B. Sperry, The Voice of Israel’s Prophets (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1952), 270–73.

[4] We will generally employ the chronology compiled by John Bright, A History of Israel, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Westminister, 1981), 465–73.

[5] See Hershel Shanks, ed., Ancient Israel (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1999), 155–65. See also David Noel Freedman, ed., Anchor Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), s.v. “Uzziah” and “Amaziah.”

[6] Bright, History of Israel, 257.

[7] Amos was likely a sheep breeder and as such would have worked with other shepherds and commanded their respect. Furthermore, it is possible that the wool trade would have required Amos to travel the trade routes of Judah, Israel, and possibly as far as Syria and Egypt. Business conducted in Israel may, in part, account for Amos’s detailed understanding of the woeful spiritual condition of the northern kingdom. See Bright, History of Israel, 262–63; see also D. Kelly Ogden,“The Book of Amos,” in Studies in Scripture, Vol. 4: First Kings to Malachi, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1993), 53.

[8] See Abraham J. Heschel, The Prophets (Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson, 2000), 39.

[9] Some examples of Israel’s sins included in Amos are profaning the temple (Amos 2:8); stealing and violence (3:10); unrepentant attitudes (4:11); bribery (5:12); excess (6:3–7); corrupt business practices (8:4–6); and false doctrine (9:10).

[10] See Heschel, The Prophets, 35.

[11] See S. Kent Brown, “The Book of Hosea,” in Studies in Scripture, 62–63. See also Heschel, The Prophets, 52–57.

[12] See Erika Bleibtreu, “Grisly Assyrian Record of Torture and Death,” in Biblical Archaeology Review, January/

[13] Sperry, The Voice, 333.

[14] Bright, History of Israel, 310.

[15] Many chronologies mark the beginning of Manasseh’s reign in 697 BC while others employ the year 687 BC. This ten-year discrepancy may be due to a ten-year coregency with Hezekiah from 697–687 BC. See Carl D. Evans, “Manasseh, King of Judah,” Anchor Bible Dictionary, 4:496–99).

[16] During this time, Babylonians, Medes (western Iran), Cimmerians and Scythians (northwestern Iran), the kingdom of Midas (Asia Minor), and others were all kept in check through military excursions. Finally, in 671 BC Assyria crushed Egypt, making her domination complete. Ironically, Assyria’s domination led, in part, to her demise. Her territories were so vast and her subjects generally despised her so deeply that it was a matter of time before the resources of the empire were spread too thin to control the rising ebb of rebellion that became generally present in her vassal kingdoms. See Bright, History of Israel, 313–16; Heschel, The Prophets, 184–92.

[17] It seems apparent from the text of Zephaniah that he is prophesying prior to the major thrust of Josiah’s reforms beginning in 622 BC because he is addressing problems that were generally done away with by the later reforms of Josiah.

[18] See Rulon D. Eames, “The Book of Zephaniah,” in Studies in Scripture,

180.

[19] See Bright, History of Israel, 315.

[20] See Bright, History of Israel, 316.

[21] See David B. Galbraith, D. Kelly Ogden, and Andrew C. Skinner, Jerusalem, The Eternal City (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 101.

[22] See Victor L. Ludlow, “The Book of Habakkuk,” in Studies in Scripture,

189.

[23] Joseph Smith, Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 330.

[24] This overview is summarized from the writings of Bright, Shanks, and Galbraith, Ogden, and Skinner.

[25] Josephus, Antiquities, 11.1.3, in Josephus: Complete Works, trans. William Whiston (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 1960); emphasis added.

[26] See Boyd K. Packer, in Conference Report, April 2000, 6.

[27] There is no agreed upon date for the prophecy of Joel (see Bible Dictionary,714). His ministry could reasonably be placed on the heels of Amos or as a contemporary of Haggai and Zechariah. We have elected to place Joel at a later date for two reasons: (1) the absence of any allusion to a king; (2) the presence of a priestly class like that upheld at the time of Haggai and Zechariah (see Joel 2:17). For more information consult Theodore Hiebert, “The Book of Joel,” in Anchor Bible Dictionary, 3:873–880. See also Jackson, Studies in Scripture, 4:359.

[28] See Bright, History of Israel, 368.

[29] See S. Kent Brown and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Between the Testaments—From Malachi to Matthew (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2002), 15–16.

[30] See Genesis 17:4–8; D&C 27:10; Smith, Teachings, 172, 337–38.

[31] Smith, Teachings, 22.