Joseph Smith and Hearty Repentance

Steven C. Harper

Steven C. Harper, "Joseph Smith and Hearty Repentance," Religious Educator 12, no. 2 (2011): 69–81.

Steven C. Harper (stevenharper@byu.edu) was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU when this was written.

Address at BYU–Hawaii on November 9, 2010.

Being convicted of his sins and having a desire for forgiveness led Joseph to the grove and later to his encounters with Moroni. Tom Lovell, ©2003 Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

Being convicted of his sins and having a desire for forgiveness led Joseph to the grove and later to his encounters with Moroni. Tom Lovell, ©2003 Intellectual Reserve, Inc.

When in 1832 Joseph Smith first narrated his vision of the Father and the Son in the woods of western New York, he told it as a story of personal repentance and forgiveness. It is a great story, a heartening story. It begins with Joseph telling us that at about age twelve he began thinking seriously about the welfare of his soul. He says that his mind became “exceedingly distressed for I become convicted of my sins . . . and I felt to mourn for my own sins and for the sins of the world.” Joseph tells us that he “cried unto the Lord for mercy” and that the Lord heard his cry in the wilderness. Joseph’s story hinges on the Savior saying to him, “Joseph my son thy sins are forgiven thee,” and ends with Joseph remembering that “my soul was filled with love and for many days I could rejoice with great Joy and the Lord was with me.”[1]

Beginning with his rich autobiographical descriptions of being convicted of his sins and how his desire for forgiveness led him to seeking, to prayer, to the grove, and later to his encounters with Moroni, Joseph provides us a wonderful, lifelong example of repentance. Moreover, the revelations the Savior gave Joseph, and the teachings Joseph gave us from the Savior’s revelations, include the restored doctrine of repentance in crystal clarity, potency, and beauty. I wish to teach and testify of this doctrine by drawing on Joseph’s autobiographies, revelations, and teachings to tell the story of Joseph Smith and hearty repentance.

Joseph lived in a culture that was much more conscious of its sins than our culture is. His ancestors had been told frequently that they were totally depraved sinners whom God would arbitrarily elect or not in an act of inscrutable will beyond their control. But the world had changed rapidly, and by the time Joseph was twelve, salvation from sin had become his responsibility. Joseph paid attention to the religious crosscurrents of his culture and to the spiritual stirrings of his soul. Growing consciousness of his teenage sins and the incessant reminders of revival preachers caused him to “become convicted” and therefore to successfully seek forgiveness in the Sacred Grove.

Joseph later wrote about his second formal act of repentance. “When I was about 17 years . . . after I had retired to bed; I had not been asleep, but was meditating upon my past life and experience. I was well aware I had not kept the commandments, and I repented heartily for all my sins and transgressions, and humbled myself before him, whose eye surveys all things at a glance.”[2] I am captivated by Joseph’s phrase that he “repented heartily.” He liked that adverb heartily. He used it frequently but not carelessly. He used it as intended, to mean “in a hearty manner,” or “with full or unrestrained exercise of real feeling; with genuine sincerity; earnestly, . . . really . . . . with courage, zeal, or spirit; . . . . with good appetite; . . . abundantly, amply . . . to the full, completely, thoroughly.”[3]

Joseph’s clear, candid, autobiographies help us understand what he meant by hearty repentance: (1) Joseph identified and confessed his sins. (2) Joseph mourned for his sins. (3) And he prayerfully sought forgiveness. Notice that Joseph did not soften sin as our culture is inclined to do. He called sin by its ugly name and identified it in himself. In one of his autobiographies, Joseph described the years between finding forgiveness in the grove and again three-and-a-half years later at his bedside: “I was left to all kinds of temptations;” he said, “and, mingling with all kinds of society, I frequently fell into many foolish errors, and displayed the weakness of youth, and the corruption of human nature; which, I am sorry to say, led me into divers temptations to the gratification of many appetites offensive in the sight of God.”[4]

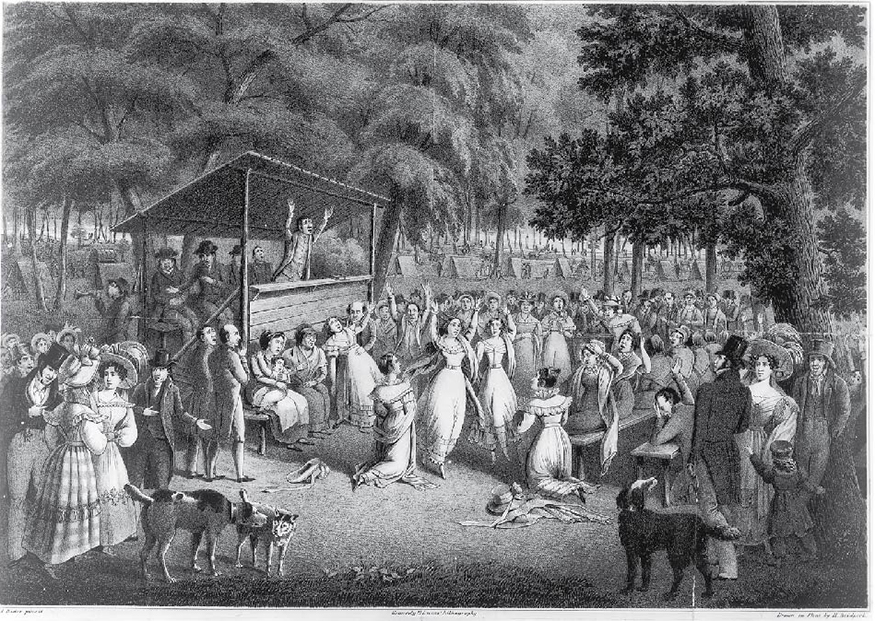

The incessant reminders of revival preachers caused young Joseph to "become convicted" and seek forgiveness in the Sacred Grove. Alexander Rider, Lithograph of an 1829 religious camp meeting, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-5818

The incessant reminders of revival preachers caused young Joseph to "become convicted" and seek forgiveness in the Sacred Grove. Alexander Rider, Lithograph of an 1829 religious camp meeting, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-5818

Joseph used the language of the revival preachers and his own vernacular to tell us that his “mind become exceedingly distressed for I become convicted of my sins . . . and I felt to mourn for my own sins.” Joseph was aware of himself. He tells us that he pondered and meditated about his predicament. He did not avoid the inner feelings that his actions were “not consistent with that character which ought to be maintained by one who was called of God as I had been” (Joseph Smith—History 1:28). He did not justify or rationalize his sins or postpone repentance. He chose to act on the heartfelt need for renewal that a generous God had planted in his soul. And he did it heartily. He did it with his whole heart. Listen carefully to Joseph’s descriptions. Listen to the way he constructs sentences. “I cried unto the Lord for mercy,” Joseph wrote. “I . . . humbled myself.” “I repented heartily for all my sins.”[5] With himself as the subject and with vigorous verbs, Joseph puts agency—by which I mean the power to repent or not—squarely on his own shoulders. He acts powerfully and penitently in his sentences to catalyze the change from convicted sinner, to sorrowful soul, to forgiven Son. As a result of such repentance, the Lord revealed to Joseph that his sins were forgiven, and Joseph was filled with love and rejoiced with great joy. To Joseph, hearty repentance was an active process. He had to do his part—confess his sins, mourn for them, and cry to the Lord—as a witness to the Savior, who would then do his part—namely, forgive.

These are the “conditions of repentance” (D&C 18:12) outlined in the scriptures, and particularly clearly in the scriptures revealed through Joseph. I testify to the paradox that it is liberating to become convicted of one’s sins, to become conscious that because of the Fall our nature is evil (see Ether 3:2). Why would conscious acceptance of my sinful nature be liberating? Because, as President Ezra Taft Benson taught, “No one adequately and properly knows why he needs Christ until he understands and accepts the doctrine of the Fall and its effect upon all mankind.”[6] The genius of Martin Luther and of every born-again Christian is the liberating recognition that it is the hearty confession of one’s sinfulness that leads the soul to depend completely on the redeeming Lord Jesus Christ.

I was a missionary teaching the restored gospel from the Book of Mormon before I finally recognized what it says on nearly every page, namely that because of the Fall of Adam and Eve, I am fallen and inherently sinful; that because of God’s grace and His Son’s infinite Atonement, I am also empowered to forsake my fallen nature, to yield to God and his invitations to come to Christ and partake of his redeeming love—to heartily repent. The Book of Mormon is full of this doctrine and of the conversion narratives of born-again Christians who acted on it. I invite you to revisit the conversion narratives of Enos, both Almas, and Amulek, in particular. And listen to these words the Savior revealed to Alma the Younger as he was unconscious, having been convicted of his sins and in the process of mourning for them. “Marvel not,” the Savior said, “that all mankind, yea, men and women, all nations, kindreds, tongues and people, must be born again; yea, born of God, changed from their carnal and fallen state, to a state of righteousness, being redeemed of God, becoming his sons and daughters; and thus they become new creatures; and unless they do this, they can in nowise inherit the kingdom of God” (Mosiah 27:25–26).

Until we acknowledge and mourn our fallen natures and determine to let Christ help us conquer them, we will not appreciate our need for Jesus Christ and his atoning sacrifice and redeeming love. It is for that reason that we want to become convicted of our sins and to mourn for them. In Joseph’s autobiographies, in the Book of Mormon conversion narratives, and in the Savior’s descriptions of his Atonement in Doctrine and Covenants sections 18 and 19, joy follows pain and suffering.

Joseph’s hearty repentance continued throughout his life. Hearty repentance characterized the four-year probationary period before he received the Book of Mormon plates as well as the months that immediately followed. Martin Harris, the prosperous Palmyra farmer and benefactor to Joseph, traveled to Harmony, Pennsylvania, in the spring of 1828 to scribe as Joseph translated the Book of Mormon. Martin resented how his wife’s gossip damaged his reputation. He asked Joseph for the chance to take the manuscript home to Palmyra to prove to her that he was no fool. Martin was older than Joseph and so supportive. How could he say no? Who would write for Joseph or provide needed money if Martin quit? Joseph asked the Lord for permission to send the manuscript with Martin. The Lord repeatedly told Joseph no but left him free to act for himself. Joseph tried to please both Martin and the Lord. He made Martin vow solemnly to show the pages only to his wife, Lucy, and a few others. Moroni, meanwhile, confiscated the seer stones. Sincerely but unwisely, Martin left for a brief trip to Palmyra with the translated manuscript. He never returned.

After a few weeks and at his wife’s urging, Joseph caught a stagecoach headed north toward his parents’ Manchester, New York, home. Hour after depressing hour he rode, reliving the extraordinary events of his life—the confusion and anxiety prior to his first vision, his feelings of sinfulness in the following years, the repeated disappointments and rebukes before receiving the plates. Each of those setbacks recurred now, bringing an ominous feeling with them. Joseph neither ate nor slept as he traveled toward an uncertain encounter. He realized he had acted unwisely and with more concern for the will of Martin Harris than his Heavenly Father. Joseph stepped off the stagecoach with twenty miles remaining between him and home. The hour was late, the night dark, and he had no way to travel but walk. A stranger walked him home, where he arrived with the dawn.

Joseph wanted to see Martin Harris immediately, so the Smiths invited him for breakfast, assuming he would come quickly. “At eight o’clock we set the victuals on the table, looking for him every moment,” Joseph’s mother wrote. “We waited till nine, and he came not; till ten, and he was not there; till eleven, still he did not make his appearance. At half past twelve we saw him walking with a slow and measured tread toward the house, his eyes fixed thoughtfully upon the ground.” Martin paused at the gate, then sat on the fence and drew his hat down over his sullen eyes.

Full of suspense, the Smiths and their guest began to eat, but Martin dropped his utensils. “Are you sick?” Joseph’s brother asked. “I have lost my soul,” Martin bawled. “I have lost my soul.” Unable to suppress his worst fears any longer, Joseph jumped up. “Oh! Martin, have you lost that manuscript? Have you broken your oath and brought down condemnation upon my head as well as your own?”

“Yes,” Martin confessed. “It is gone and I know not where.”

“Oh, my God, my God,” Joseph uttered humbly, “all is lost! What shall I do? I have sinned. It is I who tempted the wrath of God by asking him for that which I had no right to ask.” And he wept and groaned and paced the floor, forsaken.

Joseph ordered Martin to return home and find the manuscript.

“It is all in vain,” Martin replied, “for I have looked every place in the house. I have even ripped open beds and pillows, and I know it is not there.”

“Then must I return to my wife with such a tale as this?” Joseph asked. “I dare not do it. . . . And how shall I appear before the Lord? Of what rebuke am I not worthy from the angel of the Most High?” Deeply discouraged, Joseph left for home the next morning.[7]

He retired into the Pennsylvania woods and prayed mightily for redemption, pouring out sorrow, confessing weakness. Moroni appeared and returned the seer stones. Joseph looked and saw the strict words of a just God enumerating a catalog of specific sins: “Remember, remember that it is not the work of God that is frustrated, but the work of men; for although a man may have many revelations, and have power to do many mighty works, yet if he boasts in his own strength, and sets at naught the counsels of God, and follows after the dictates of his own will and carnal desires, he must fall and incur the vengeance of a just God upon him.” The Lord’s words pierced Joseph, convicting him of sin. “Behold, you have been entrusted with these things, but how strict were your commandments; and remember also the promises which were made to you, if you did not transgress them.” Joseph recalled Moroni’s commission to be responsible for the sacred records and powers of translation. But Joseph had often been persuaded by men, especially Martin Harris, to transgress these commands. “How oft you have transgressed the commandments and the laws of God, and have gone on in the persuasions of men,” the Lord continued firmly. “You should not have feared man more than God.” Martin Harris rejected the Lord’s words, but Joseph knew better. By yielding to Martin, Joseph turned his back on the Savior’s will. “Thou wast chosen to do the work of the Lord,” Jesus warned, “but because of transgression, if thou art not aware thou wilt fall” (D&C 3:3–9). These words “were hard for a young man who had lost his first-born son and nearly lost his wife [in childbirth], and whose chief error was to trust a friend, but there was comfort in the revelation as well.”[8]

The tone of the heavenly revelation switched dramatically. “Remember,” it says halfway through, “God is merciful; therefore repent of that which thou hast done which is contrary to the commandment which I gave you, and thou art still chosen, and art again called to the work” (D&C 3:10).

Joseph received the words gladly, as if they were cool water for his singed soul. They illustrated God’s perfectly harmonized justice and mercy. They showed that repentance fully qualifies one for mercy, whereas stubborn willfulness leads to God’s just vengeance. The revelation marked a turning point for the young seer. Only twenty-two years old, he would no longer be bound by his youthful temptations. He was not perfect, but his eye was becoming single to God’s glory. Moroni had taken the seer stones while Joseph acted on the revelation’s command to repent. Then in September 1828, one year after he first received them, the plates and the marvelous stones were again entrusted to Joseph. By choosing to repent heartily, Joseph was still chosen and again called to the work of translating the Book of Mormon.

Joseph’s subsequent revelations repeatedly emphasize repentance. As he called early missionaries, the Lord told them in various ways to “say nothing but repentance” (D&C 11:9). To two Whitmer brothers, the Lord elaborated a rationale for helping others repent. “The thing which will be of the most worth unto you,” he told them, “will be to declare repentance unto this people, that you may bring souls unto me, that you may rest with them in the kingdom of my Father” (D&C 15:6, 16:6). To Oliver Cowdery and David Whitmer, the Lord elaborated much further, linking repentance to his infinite atonement. “Remember the worth of souls is great in the sight of God,” the Savior declared (D&C 18:10).

We know this passage so well that I fear we take it for granted. Let me contextualize it a bit in an effort to increase appreciation for its profundity and power. It is part of a revelation to Apostles. It tells Apostles what they should think about and do. And if we had to boil it down to a single sentence, it would be that Apostles are to help people repent because repentance results in joy. “I command all men everywhere to repent,” the Lord declares before he commands the Apostles to remember how valuable souls are (v. 9). Please see and understand that Jesus commands us all to repent because he values us so much. How much? “The Lord your Redeemer suffered death in the flesh; wherefore he suffered the pain of all men, that all men might repent and come unto him. And he hath risen again from the dead, so that he might bring all men unto him, on conditions of repentance” (vv. 11–12). This is the restored rationale of repentance. We “are called to cry repentance unto this people”(v. 14) because their souls are of such great worth to the Lord Jesus Christ, who suffered for them.

To Martin Harris, the Savior waxed even more explicit about the link between repentance and his Atonement. Early in June 1829, Joseph and Martin asked Palmyra printer Egbert Grandin to publish the Book of Mormon. Grandin was reluctant, agreeing to the controversial project only after Martin returned with news that a Rochester printer would do the publishing if Grandin refused. They worked out an agreement in which Grandin would print and bind five thousand copies of the Book of Mormon for three thousand dollars, with Martin putting up more than 150 acres of land as collateral. Martin mortgaged the land on August 25. He had eighteen months to pay the debt, hopefully with proceeds from book sales, or else Grandin could sell the property.[9] Once the paperwork was finished, Grandin’s employees began printing.

In January 1830, Joseph and Martin agreed to share profits from the Book of Mormon until Martin’s mortgage was paid. In March, as the first copies came from the press, Martin became alarmed. He met Joseph on the road from his Pennsylvania home to Palmyra to check on the printing. Arms full of books, a distraught Martin Harris told Joseph, “the books will not sell for nobody wants them.”

“I think they will sell well,” Joseph responded.

“I want a commandment,” Martin demanded, seeking a reassuring revelation.

“Fulfill what you have got,” replied Joseph, referring to the Lord’s earlier instructions to Martin (see D&C 5: 17).

“I must have a commandment,” Martin said, increasingly anxious.

Martin stayed that night with Joseph at the Smith home. Restless, he had an anxious dream that an enormous dog was pouncing on him. He rose in the morning, again demanded a revelation, and left for home. That afternoon Joseph received Doctrine and Covenants section 19 as Oliver Cowdery scribed.[10]

Six times in that section the Savior commands Martin to repent in order to escape suffering that the Lord alone could fathom. “I . . . have suffered these things for all, so that they might not suffer if they would repent,” the Savior told Martin, “but if they would not repent they must suffer, even as I” (D&C 19:16–17). Elder David B. Haight taught that “if we could feel or were sensitive even in the slightest to the matchless love of our Savior and his willingness to suffer for our individual sins, we would cease procrastination and clean the slate, and repent of all our transgressions. This would mean keeping God’s commandments and setting our lives in order, searching our souls, and repenting of our sins, large or small.”[11]

Through Joseph, the Lord commanded the talented but arrogant William W. Phelps to repent and, in the process, taught us how to discern real repentance: “By this ye may know if a man repenteth of his sins—behold, he will confess them and forsake them” (D&C 58:43). We all know that one of the conditions of repentance is confessing our sins. But why? Doesn’t the omniscient Lord know our sins? The question assumes that the Lord requires confession for his benefit, but perhaps he requires it for ours. Joseph said that he humbled himself in order to repent. The humility required to confess our sins is a condition of repentance. There is no repentance without penitence. And penitence is lacking in the soul who is unwilling to confess their sins. Thus contrite confession is a key to repentance. So is forsaking sin. The willingness to give away all our sins to know God is evidence that we have met the conditions of repentance. Compare King Limhi’s prayer, “O God . . . I will give away all my sins to know thee” (Alma 22:18), with Augustine’s, “Grant mechastityand continence, but not yet” (da mihi castitatem et continentiam, sed noli modo).[12]

Joseph Smith received a revelation (D&C 66) for a man named William McLellin. Like many of us, William was deciding whether to be like Limhi or Augustine. Prior to meeting Joseph, William secretly prayed that God would “reveal the answer to five questions through his prophet, and that too without his having any knowledge of my having made such request.” In 1848, ten years after bitterly parting ways with Joseph Smith, William wrote, “I now testify in the fear of God, that every question which I had thus lodged in the ears of the Lord . . . were answered to my full and entire satisfaction. I desired it for a testimony of Joseph’s inspiration. And I to this day consider it to me an evidence which I cannot refute.”[13]

I count twenty-two commandments in the thirteen verses of section 66, and the first of them is “repent . . . of those things which are not pleasing in my sight, saith the Lord, for the Lord will show them unto you” (D&C 66:3). William kept some of the commands all of the time, and all of the commands some of the time. But he also broke several specific commandments consciously and in some cases blatantly. All the while he testified “that Joseph Smith is a true Prophet or Seer of the Lord and that he has power and does receive revelations from God, and that these revelations when received are of divine Authority in the church of Christ.”[14] When William broke the command to “commit not adultery—a temptation with which thou hast been troubled” (D&C 66:10), he was called before a bishop’s council for Church discipline.

He did not heartily repent. He was not convicted of his sins. He was not humble. He did not cry unto the Lord for mercy. He only half-heartedly confessed. He said that he thought that Church leaders were not being faithful, so “consequently <he> left of[f] praying and keeping the commandments of God, and went his own way, and indulged himself in his lustfull desires.” Joseph Smith asked William whether he had actually witnessed the sins with which he had charged Church leaders. No, William answered, he judged from gossip. The clerk keeping the minutes of the disciplinary council couldn’t resist entering the important lesson into the record: “O!! Foolish Man! What excuse is [it] that thou rendereset, for thy sins, that because thou hast heard of some mans transgression, that thou Shouldest leave thy God, and forsake thy prayers, and turn to those things that thou knowest to be contrary to the will of God, we say unto thee, and to all Such, beware! beware! for God will bring the[e] into judgment for thy sins.”[15] The Church excommunicated the unrepentant William, and he spent the rest of his long life struggling to resolve the dissonance between his sure testimony of Joseph the revelator and his unwillingness to obey the revelation’s commandment to repent.

A main difference between Joseph Smith and William McLellin is hearty repentance. The decision to repent heartily or not came from inside each of them. Both had the same gospel of repentance clearly explained to them. Both covenanted, signifying their willingness to take the Lord’s name upon them, always remember him, and keep the commandments he had given them. William didn’t have greater temptations. He had less love for God, less will to repent.

Brothers and sisters, will you join with me in a commitment to repent heartily? But what if I’m lacking the will to repent, you might ask. What if I’m like Augustine or William McLellin, knowing well that repentance is needed but lacking the desire, opting to postpone hearty repentance and justify sinfulness a little longer? In that case, I urge you to pray for the desire to desire to repent. Begin where you are and keep going until you become convicted of your sins. You will know that you’re becoming convicted of your sins when they begin to cause you to mourn. You may notice that your feelings transition from what Mormon called “the sorrowing of the damned” (Mormon 2:13), meaning the frustration of those who cannot find happiness in sin, and become more akin to the pain and torment Alma described of the period that he was “harrowed up by the memory of [his] many sins” just before Jesus replaced those memories with sweet, exquisite joy (Alma 36:19).

As part of my invitation to you, I add another adverb to Joseph’s description of hearty repentance. I invite you to repent relentlessly. Joseph taught that frequent, feigned repentance trifles with the Atonement of Jesus Christ.[16] But that is not what I mean by relentless repentance. By repentance I mean repentance and its conditions as defined and illustrated in the restored scriptures. And by relentless I mean that we doggedly do not relent to what Lehi called “the will of the flesh and the evil which is therein, which giveth the spirit of the devil power to captivate” (2 Nephi 2:29). And I mean that as often as we fall short of that standard we repent. I mean that we never relent to the sin of giving up on the worth of our own souls, for which the Savior paid infinitely. If we can see ourselves as he sees us, we will repent relentlessly. We will never give up on him or on us. Relentless repentance means that by humbling ourselves and crying to the Lord we gain and exercise power over Satan and consistently refuse to give him power over us.[17] I mean what Shakespeare meant when he had Hamlet urge,

Confess yourself to heaven;

Repent what’s past; avoid what is to come;

Refrain tonight,

And that shall lend a kind of easiness

To the next abstinence; the next more easy;

For use can almost change the stamp of nature,

And either master the devil, or throw him out

With wondrous potency.[18]

Relentless repentance is like scrambling up and finally conquering a long, steep slope. There may be backsliding, scraped knees, and muscles that scream at the work required to continue the unyielding ascent. The mountain may seem to conquer the will to continue, to mock the determination to surmount. But the relentless repenter keeps climbing the mountain. Sisters and brothers, keep climbing your mountains. Repent relentlessly. Help each other repent relentlessly so that you can rejoice with the Savior in the repentant soul. Allow each other to repent so sorrow can be replaced with compensatory joy. Allow yourself to repent, as Joseph did; appropriately confess and mourn your sinfulness as a prerequisite to having your soul filled with love and rejoicing. Cry unto the Lord for mercy, and he will hear your cry in the wilderness and say to you as he said to Joseph more than once, “Your sins are forgiven you; you are clean before me; therefore, lift up your heads and rejoice” (D&C 110:5).

Notes

[1] The Papers of Joseph Smith: Autobiographical and Historical Writings, vol. 1, ed. Dean C. Jessee (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989), 5–6.

[2] The Papers of Joseph Smith, 127.

[3] Oxford English Dictionary, “heartily.”

[4] Papers of Joseph Smith, 275–76. A few years later, while preparing Joseph’s history for publication, Willard Richards redacted this passage. Perhaps at Joseph’s request, Willard softened Joseph’s confession by deleting the words that are struck through in the quote and by adding the following ones: “In making this confession, no one need suppose me guilty of any great or malignant sins. A disposition to commit such was never in my nature. But I was guilty of levity, and sometimes associated with jovial company, etc., not consistent with that character which ought to be maintained by one who was called of God as I had been” (Joseph Smith—History 1:28).

[5] The Papers of Joseph Smith, 5–7; 275–76.

[6] Ezra Taft Benson, “The Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants,” Ensign, May 1987, 83–86.

[7] Steven C. Harper, Joseph the Seer (Provo, UT: Harper Publishing, 2005), 51–53.

[8] Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Knopf, 2005), 68.

[9] Martin Harris, Mortgage to Egbert B. Grandin, August 25, 1829, Mortgages, Liber 3, 325, Wayne County Clerk’s Office, Lyons, New York.

[10] Joseph Knight, Manuscript History, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[11] David B. Haight, “Our Lord and Savior,” Ensign, May 1988, 23.

[12] Augustine, Confessions, 8.7.17.

[13] The Journals of William E. McLellin, 1831–1836, ed. Jan Shipps and John W. Welch (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 57.

[14] The Journals of William E. McLellin, 87.

[15] The Papers of Joseph Smith: Journal, 1832–1842, vol. 2, ed. Dean C. Jessee (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 241.

[16] “Daily transgression & daily repentance is not that which is pleasing in the sight of God,” Willard Richards, Pocket Companion, 15–22, Church History Library; possibly a discourse of June 27, 1839, as posited by The Words of Joseph Smith, ed. Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1980) 3–6.

[17] “The devil has no power over us only as we permit him,” Joseph Smith, discourse, January 5, 1841, Nauvoo, Illinois, William Clayton’s Private Book, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[18] William Shakespeare, Hamlet, 3.4.165–70.