Precept upon Precept: The Succession of John Taylor

Patrick A. Bishop

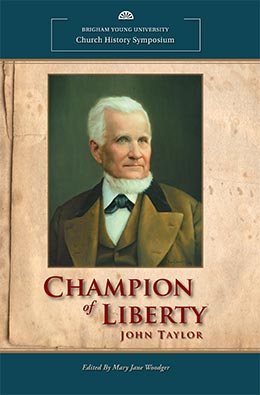

Patrick A. Bishop, “Precept upon Precept: The Succession of John Taylor,” in Champion of Liberty: John Taylor, ed. Mary Jane Woodger (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 233–72.

Patrick A. Bishop was a coordinator of seminaries and institutes of religion in Casper, Wyoming, when this was published.

To members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, succession to the Presidency of the Church has become a clear process. Succession was not always so clear, however. As we study the call of John Taylor to the Quorum of Twelve Apostles and watch him “move up through the ranks of that circle,”[1] several principles regarding succession appear “line upon line, precept upon precept” (2 Nephi 28:30). These principles follow: First, seniority in the quorum was initially based on age when the quorum was first established. Thereafter, seniority was in accordance with the date of ordination.[2] Second, seniority is based on the date one becomes a member of the Quorum of the Twelve and not the date of a prior ordination to the office of Apostle. Third, seniority is based on continuous service in the quorum without interruption.[3] Fourth, although a man may be the senior Apostle, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles must pass a motion to reorganize the First Presidency, and then the Quorum of the Twelve unanimously selects the new president, and he is sustained by the body of the Church.

First precept: Seniority was initially based on age when the quorum was first established. Thereafter, seniority was in accordance with the date of ordination.

The first members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles were named on February 14, 1835. From that date until April 26, each of these brethren were ordained as Apostles and set in the Quorum of the Twelve. Their names and ages are listed chronologically by their date of ordination: Lyman E. Johnson (twenty-three), Brigham Young (thirty-five), Heber C. Kimball (thirty-three), Orson Hyde (thirty), David W. Patten (thirty-five), Luke S. Johnson (twenty-seven), William E. McLellin (twenty-nine), John F. Boynton (twenty-three), Orson Pratt (twenty-three), William Smith (twenty-three), Thomas B. Marsh (thirty-five), and Parley P. Pratt (twenty-seven).

Less than a week later, on May 2, Joseph Smith put order to the quorum and gave directions on how their council meetings should be conducted. The record from the Kirtland High Council Minutes from this date states:

According to appointment the Presidency, the Twelve a part of the Seventy, and some other Elders of the church met in conference this morning in order to consult the affairs of the church &c. Conference was opened by Elder Brigham Young by prayer. President J. Smith Junr. presiding. After conference was opened and the Twelve took their seats, he stated that it would be the duty of the Twelve to appoint the oldest one of their number to preside in their councils, beginning at the oldest and so on until the youngest has presided and then beginning at the oldest again. &c. The Twelve took their Seats regularly according to their ages as follows. T. B. Marsh David W. Patten, Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball Orson Hyde, Wm. E. McLelin Parley P. Pratt, Luke Johnson William Smith Orson Pratt John F. Boynton & Lyman Johnson.[4]

It is generally assumed that Thomas B. Marsh became President of the Quorum of the Twelve in the above-mentioned meeting on May 2, 1835, although no mention of a president to the quorum is made until seven months later. The minutes only state that each of the Twelve was to preside in their council meetings until they had all done so and “then begin at the oldest again.”[5] The earliest date that a President of the Twelve is actually called by name is January 22, 1836. Although Thomas B. Marsh was probably considered President of the Quorum of the Twelve before this date, below is the first document that shows him as such.

By May of 1838, there were four vacancies in the Quorum of the Twelve: John F. Boynton, Luke S. Johnson, Lyman E. Johnson, and William McLellin had all apostatized.[6] To fill these four vacancies, the Prophet Joseph Smith received a revelation on July 8, 1838, in Far West, Missouri. While meeting with Sidney Rigdon, Hyrum Smith, Edward Partridge, Isaac Morley, Jared Carter, Samson Avard, Thomas B. Marsh, and George W. Robinson, Joseph joined the men in pleading with God in prayer, saying, “Show unto us Thy will, O Lord, concerning the Twelve.”[7]

This revelation named John Taylor to be ordained as one of the members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles to fill the vacancies of those who apostatized. This revelation uttered through Joseph Smith, now section 118 of the Doctrine and Covenants, declared in part, “Let my servant John Taylor, and also my servant John E. Page, and also my servant Wilford Woodruff, and also my servant Willard Richards, be appointed to fill the places of those who have fallen and be officially notified of their appointment” (v. 6).

Of particular interest are the names of those called to the Twelve with John Taylor in this revelation. John Taylor was thirty years old, John E. Page, thirty-seven, Wilford Woodruff, thirty-one; and Willard Richards, thirty-four. Notice that John Taylor was the youngest of those called at this time, yet he was named first by the Lord. A council was held the next day, July 9, and it was decided how each individual was to be notified of their appointment. John E. Page was the only one named in the revelation who was in the region. He had returned from a mission in Canada where he had baptized over six hundred converts and then led them back to Kirtland in May of 1838. After returning from his mission, Page traveled to Missouri, arriving by September of that year. Wilford Woodruff was in the Fox Islands (Maine), Willard Richards was in England, and John Taylor was in Canada. Each was mailed a letter informing him of his appointment. Although it probably took some time for the letter revealing their calls to the Twelve to appear in the mail, John Taylor and Wilford Woodruff each knew prior to their calls by the whispering of the Spirit.[8] John Taylor’s reminisced about his call:

I will state that I was living in Canada at the time, some three hundred miles distant from Kirtland. I was presiding over a number of churches in that region, in fact, over all of the churches in Upper Canada. I knew about this calling and appointment before it came, it having been revealed to me. But not knowing but that the devil had a finger in the matter, I did not say anything about it to anybody. [Brother Woodruff here spoke up and said that he was on the Fox Islands, which were farther away still; and also knew, by the Spirit, that he would be called to the apostleship.] A messenger came to me with a letter from the First Presidency, informing me of my appointment, and requesting me to repair forthwith to Kirtland, and from there to go to Far West. I went according to the command.[9]

John Taylor arrived in Far West in October, and during the quarterly conference in Far West, he spoke. The Far West record states, “Elder John Taylor, from Canada, by request, gave a statement, of his feelings respecting his being appointed as one of the Twelve. He said he was willing to do anything, which God would require of him, by the assistance of the Lord. After which it was voted by the Conference that Br John Taylor fill the vacancy of one of the Twelve.”[10]

Soon after this the Prophet Joseph Smith had been taken prisoner and was in the jail called Liberty. Thus, he could not be present at the ordination of John Taylor. Therefore, on December 19, 1838, Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball ordained John Taylor and John E. Page to the office of Apostle and as members of the Quorum of the Twelve. The record is not clear as to who was ordained first on that day, but John E. Page was John Taylor’s elder by seven years, and he was placed ahead of him in the seniority of the Twelve.

After the ordinations of Elders Page and Taylor, part of the revelation given in 1838 was fulfilled. However, Wilford Woodruff and Willard Richards were still awaiting their ordinations as prescribed in the revelation. One of these ordinations took place in April as the Twelve left from Far West for England. John Taylor gives more details of this ordination of Wilford Woodruff: “Brother Woodruff was ordained, after the scenes of the war at Far West; but I think it was right in the midst of the war when Brother Page and I were ordained. Brother Woodruff was ordained on the cornerstone of the foundation of the temple in Far West, on the 26th of April, 1839, when we went to fulfil this same revelation that you have heard read, and I helped to ordain him.”[11]

What is significant about these events is that Elder Taylor was present and laid his hands on Elder Woodruff as he stood on the cornerstone for the temple and helped to ordain him to the apostleship. Yet Elder Woodruff’s name was placed above Elder Taylor’s in the seniority of the Twelve for the next twenty-two years.[12] Woodruff was one year older than Taylor, and some have thought this was the reason for the order of seniority.

One item concerning the relationship of age and seniority that needs clarification is contained in a letter dated January 16, 1839. On this date, Sidney Rigdon, Joseph Smith, and Hyrum Smith, the First Presidency, wrote a letter to Heber C. Kimball and Brigham Young. The ending to the letter is significant wherein it states, “Appoint the oldest of those twelve who were firs appointed, to be the President of your Quorum.”[13]

Some might interpret this to mean that the oldest man should always become President of the Quorum. However a careful reading shows that the First Presidency said that the “oldest of those twelve who were first appointed” should be made President. John E. Page was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve at this point and was thirty-nine, the oldest man in the Quorum. Lyman Wight, who was even three years older than John E. Page, would later join the Quorum. Yet Brigham Young who was ordained back in February of 1835 was the President of that Quorum because he was the “oldest of those twelve who were first appointed.” There is still no evidence, however, that age was the guiding principle in determining who the next President of the Quorum should be after all of those who “were first appointed” had died. Age only determined the rotation of who presided in their council meetings.

Gary Bergera has argued that up until April 1861 age was the governing factor in deciding the succession question. He quotes Brigham Young’s April 6, 1861, sermon to support this claim. “The oldest man—the senior member of the first Quorum will preside, each in his turn,” he explained, “until every one of them has passed away. . . . Bro. Orson Hyde and br. Orson Pratt, sen., are the only two that are now left in the Quorum of the Twelve that br. Joseph selected. Perhaps there are a great many here who never thought of these ideas, and never heard anything about them.”[14] This quotation, however, is taken out of context in supporting that age was the primary factor in deciding seniority in the Twelve. The context of this talk by Brigham Young was the Quorums of Seventy and not the Quorum of the Twelve. Furthermore, President Young stated: “I will remark a little further. When Bro. Lyman Wight was ordained into the Quorum of the Twelve, he was an older man than I, and yet I was the President of the Twelve. He and the others believed that he ought to be the President, but you can read the revelation in the Book of Doctrine and Covenants. The Lord said unto Joseph, I have given to you my servant, Brigham, to be the President of the Twelve. This will explain all that is now necessary on this point. To return to the Seventies.”[15]

It seems clear that Brigham Young knew and understood that however one succeeded to the Presidency of the Quorum of the Twelve, it was not based on their age alone, but rather on something else, of which he does not give any indication besides quoting a revelation naming him as President. What is most interesting about this revelation, currently Doctrine and Covenants 124, naming Brigham Young as President of the Twelve is how the revelation orders the names of the Twelve: “I give unto you my servant Brigham Young to be a president over the Twelve traveling council; which Twelve hold the keys to open up the authority of my kingdom upon the four corners of the earth, and after that to send my word to every creature. They are Heber C. Kimball, Parley P. Pratt, Orson Pratt, Orson Hyde, William Smith, John Taylor, John E. Page, Wilford Woodruff, Willard Richards, George A. Smith” (D&C 124:127–29). Notice again as in section 118, John Taylor appears before both John E. Page and Wilford Woodruff although they are both older.

Interestingly, the last time that John Taylor’s name was placed behind Wilford Woodruff’s in the minutes of the meetings of the Church was in the April 1861 general conference. Six months later, President Brigham Young revealed part of the Lord’s will regarding seniority in the Twelve. In the October 1861 general conference of the Church, Elder John Taylor was again asked to read the names for a sustaining vote. Reading the names, he again placed Elder Woodruff’s name ahead of his. According to the record, President Young apparently interrupted the voting:

Elder John Taylor in presenting the names of the Twelve Apostles to the Conference meeting, called the name of Elder Wilford Woodruff before his own; upon which Prest. Young directed the Clerk, J. T. Long, to place Bro. Taylor’s name above Bro. Woodruff’s as Elder Taylor was ordained four or five months before Elder Woodruff. It was suggested to the President that Elder Woodruff, Taylor and Richards were called by revelation at the same time, and their places had been arranged from the date of the calling, according to age, instead of the date of ordination. Prest. Young said the calling was made in accordance with the date of ordination. He spoke of it now, because the time would come, when a dispute might arise about it. According to this the Quorum in 1841 should have been arranged John Taylor, Wilford Woodruff, George A. Smith and Willard Richards.[16]

This new order is precisely the same order in which the Lord named John Taylor, Wilford Woodruff, and Willard Richards in the 1838 revelation. Twenty six years from the time the Quorum of the Twelve was established this first precept was clear. Seniority in the quorum was based on age when the quorum was first established; thereafter seniority was in accordance with the date of ordination.[17]

Second precept: Seniority is based on the date one becomes a member of the Quorum of the Twelve and not a prior ordination to the office of Apostle.

Something not generally known is that there have been many brethren ordained as Apostles who were never members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Many believe that this was the case with Paul, the New Testament Apostle.[18] Those in John Taylor’s lifetime who were ordained to the apostleship either before they were made members of the Quorum of the Twelve or without ever becoming members of the Twelve include Jedediah Grant, John W. Young, Daniel H. Wells, Joseph A. Young, Brigham Young Jr., and Joseph F. Smith. The first four named never became part of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles; therefore, no attention will be given them.[19]

Brigham Young Jr. was ordained an Apostle by his father on February 4, 1864, in a private ordination that was not made known until two months later in another private setting. On April 17, 1864, “Pres. Brigham Young, John Taylor, and Geo. A. Smith met and prayed.”[20] Taylor and Smith were among Young’s most trusted members of the Twelve. Wilford Woodruff, Church historian at the time, indicates much more took place at this prayer meeting. President Young said, “I am going to tell you [John Taylor and George A. Smith] something that I have never before mentioned to any other person. I have ordained my sons, Joseph A., Brigham, and John W., apostles and my counsellors, have you any objections? Brother Taylor, George A. Smith said that they had not that it was his own affair and they considered it under his own direction. . . . Signed John Taylor, and George A. Smith.”[21] All the reasons for ordaining his sons at this time to the office of Apostle may remain unresolved.

About two years later, on July 1, 1866, another private ordination to the apostleship was performed by Brigham Young. Wilford Woodruff records of this event:

At the Close of the meeting I met at the Prayer Circle with Presidet Young John Taylor W. Woodruff G. A. Smith G. Q. Cannon & Joseph F Smith. John Taylor Prayed & President Young was mouth. At the close of the Prayer Presidet Young arose from his knees. . . . Of a sudden he stoped & Exclaimed hold on, “Shall I do as I feel led? I always [feel] well to do as the Spirit Constrains me. It is my mind to Ordain Brother Joseph F Smith to the Apostleship, and to be one of my Councillors.” He then Called upon Each one of us for an Expression of our Feelings and we Individually responded that it met our Harty approval. . . . We laid our hands upon him, Brother Brigham being mouth & we repeating after him in the usual Form. . . . After we had finished up Stairs we descended to the Historians office & wrote this statement which we signed at 20 minuts past 6 oclok of the Afternoon of Sunday July first Eighteen-hundred & Sixty Six. John Taylor Wilford Woodruff George A Smith & G. Q. Cannon.[22]

It is interesting to note that John Taylor was one of the first to know about the private ordinations of both Brigham Young Jr. and Joseph F. Smith. If the date of ordination to the apostleship was the determining factor in seniority in the Twelve, when Brigham Young Jr. and Joseph F. Smith were placed in the Twelve, Brigham Young Jr. would have become President of the Twelve before Joseph F. Smith.

In 1867, Amasa Lyman of the Twelve was excommunicated and released from his position in the quorum. This vacancy was filled by Joseph F. Smith. Then in 1868, Heber C. Kimball of the First Presidency died, and George A. Smith was called into the First Presidency. George A. Smith’s vacancy was then filled by Brigham Young Jr. This set of circumstances raises another question: of Brigham Young Jr. and Joseph F. Smith, who was the senior? Brigham had been ordained an Apostle first, but Joseph was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve first. From 1868 on, Brigham Young Jr.’s name was placed ahead of Joseph F.’s in the records.

Not until April 5, 1900, was the question of date of ordination or the date of entrance into the quorum resolved. In a meeting of the First Presidency and the Twelve this issue was brought up. It was decided that the date of entrance into the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles rather than the date of ordination to the office of Apostle determined seniority.[23]

It could be interpreted that this was a change in policy, but a better and more accurate observation is that this step in the succession question harmonized several revealed gospel principles. Private ordinations had often been problematic when these ordinations affected public administration. The Lord revealed in 1831 the pattern for officers that publicly administer in the Church, “Again I say unto you, that it shall not be given to any one to go forth to preach my gospel, or to build up my church, except he be ordained by some one who has authority, and it is known to the church that he has authority and has been regularly ordained by the heads of the church” (D&C 42:11). In other words, Brigham Young Jr.’s and Joseph F. Smith’s private ordinations were not made “known to the Church that they had authority,” and Brigham Young Jr. was only ordained by the head and not “ordained by the heads of the church.” Furthermore, Joseph F. Smith was ordained by the “heads of the Church” and was the first of the two to become “known to the church” in October of 1867. This shows the significance in turning to the revealed word of the Lord to answer questions of this nature. Up to this date, a practical application of this scriptural text regarding succession was not realized. Therefore from 1900, seniority was based on the date one became a member of the Quorum of the Twelve and not a prior ordination to the office of an Apostle.

Third precept: Seniority is based on continuous service in the Quorum without interruption.

The circumstances surrounding this precept could seem contentious and controversial within the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.[24] Admittedly, there have been times in the history of both the meridian Church and the latter-day Church that the Apostles have not seen things in the same light and have perhaps harbored some ill feelings against each other (see Galatians 2:11). The Lord himself declared, “My disciples, in days of old, sought occasion against one another, and forgave not one another in their hearts; and for this evil they were afflicted and sorely chastened” (D&C 64:8).

Early in the history of the Church, Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt were both dropped as members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. The question arose, should their seniority remain intact while they were out of the quorum, or should their seniority be based on the date they reentered the quorum? On May 4, 1839, Orson Hyde was released from the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles for siding with apostate Thomas B. Marsh during the Missouri persecutions. Thomas was still acting as President of the Quorum of the Twelve even though he had apostatized from the Church and had taken an oath that the Saints in Missouri had formed a “‘Destruction Company,’ for the purpose of burning and destroying” to avenge themselves against the people and government in the state of Missouri.[25] Orson Hyde, being “overcome by the spirit of darkness,” signed a solemn affidavit on October 24, 1838, siding with Marsh.[26] Orson Hyde wrote, “Most of the statements in the foregoing disclosure I know to be true; the remainder I believe to be true.”[27]

President John Taylor gave insight into the alliance between Thomas and Orson: “In coming into Far West, I heard about him [Thomas B. Marsh] and Orson Hyde having left. It would be here proper to state, however, that Orson Hyde had been sick with a violent fever for some time, and had not yet fully recovered therefrom, which, with the circumstances with which we were surrounded and the influence of Thomas B. Marsh, may be offered as a slight palliation for his default.”[28]

As a result of this affidavit, many Saints lost their lives during the extermination of the Saints from Missouri and the Prophet Joseph, along with many of the presiding brethren, were incarcerated in Liberty Jail. Subsequently on May 4, 1839, Orson Hyde was dropped from the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Not a month later, Elder Hyde repented and sought reconciliation to the Prophet and the Church. After meeting with his brethren of the Twelve and the First Presidency, Orson Hyde was restored to his former standing in the Twelve on June 27, 1839. It is most interesting that these brethren of the Twelve, who had “sought occasion” against each other, had forgiven each other and become “reconciled” (Matthew 5:24).

A similar scenario played out on August 20, 1842, when Orson Pratt was informed by John C. Bennett that Joseph Smith had tried to seduce his wife while he was in England, and that promiscuous sexual relations were not only secretly taught by the Prophet and the Patriarch, but were indulged in by the Prophet and other Church leaders in Nauvoo. When Orson’s wife backed up Bennett’s story, having been deceived on the matter herself, Pratt became so wrought up that instead of going to the Prophet and learning the truth for himself, he smoldered indignantly, becoming extremely agitated.

John Taylor later wrote of his involvement with Orson Pratt during this time “When I saw that he was very severely tried . . . I talked with him for nearly two hours, to prevent, if possible, his apostasy.”[29] He was excommunicated on August 20, 1842.

After making a thorough investigation, Orson Pratt became convinced of the falseness of John C. Bennett’s claims that he was acting under the Prophet’s direction when he made inappropriate advances on Orson’s wife, Sarah. John deceived Sarah by introducing the false doctrine of “spiritual wifery.” Before Orson and his wife’s excommunication the previous August, the Prophet Joseph personally worked with Orson for twelve days to no avail. In January 1843, however, he learned that he was misinformed from a “wicked source.”[30] Orson came to the conclusion that his wife had been deceived also. He then exonerated the Prophet from blame and convinced his wife that Bennett was the guilty one. Upon Orson’s return, Joseph wrote, “This council was called to consider the case of Orson Pratt who had previously been cut off from the Church for disobedience, and Amasa Lyman had been ordained an Apostle in his place. I told the quorum: you may receive Orson back into the quorum of the Twelve and I can take Amasa into the First Presidency. . . . At three o’clock, council adjourned to my house; and at four I baptized Orson Pratt and his wife . . . in the Mississippi river, and confirmed them in the Church, ordaining Orson Pratt to his former office in the quorum of the Twelve.”[31]

Like Orson Hyde before him, Elder Pratt was restored by Joseph to his former office and seniority in the Quorum of the Twelve. Yet another example of the brethren obeying the Lord’s command to become “reconciled” one to another. Yet this still did not dismiss the fact that both Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt had had an interruption in their service in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

Some time between 1869 and 1871, President George A. Smith, who was then in the First Presidency, approached Elder Taylor about the matter of succession, Taylor recounted the discussion in 1881:

Another question arose. . . . Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt had both of them been disfellowshipped and dropped from their quorum, and when they returned, without any particular investigation or arrangement, they took the position in the quorum which they had formerly occupied, and as there was no objection raised, or investigation had on this subject, things continued in this position for a number of years. Some ten or twelve years ago, Brother George A. Smith drew my attention to this matter. I think it was soon after he was appointed as counselor to the first presidency; and he asked me if I had noticed the impropriety of the arrangement. He stated at the same time that these brethren having been dropped from the quorum could not assume the position that they before had in the quorum; but that all those who remained in the quorum when they had left it must necessarily take the precedence of them in the quorum. He stated, at the same time, that these questions might become very serious ones, in case of change of circumstances arising from death or otherwise; remarking also, that I stood before them in the quorum. I told him that I was aware of that, and of the correctness of the position assumed by him, and had been for years, but that I did not choose to agitate or bring up a question of that kind. Furthermore, I stated that, personally, I cared nothing about the matter, and, moreover, I entertained a very high esteem for both the parties named; while, at the same time, I could not help but see, with him, that complications might hereafter arise, unless the matters were adjusted.[32]

There was still an issue at stake regarding the succession question: should members of the Quorum who have fallen receive their former place of seniority in the quorum? It was an issue that started to circulate amongst those in the valleys of the Great Salt Lake. The Salt Lake Tribune published an article entitled “The Two Orsons and the Succession” dated September 16, 1871, by an anonymous writer. If Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt lost their seniority in the Twelve, the writer said, it would amount to a “grand impeachment.”[33] He then continued to slander President Brigham Young. Yes, there was a succession question but there is no evidence that Orson Hyde or Orson Pratt held any negative feelings toward Brigham Young or John Taylor over this issue. And, as quoted earlier, John Taylor held “a very high esteem” for both Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt.

As further evidence that President Orson Hyde held no aspirations to become President of the Church and harbored no negative feelings toward the before mentioned parties, he wrote a letter in response to the Salt Lake Tribune article addressed to George A. Smith, September 23, 1871.

Spring City Sept. 23rd 1871

Prest G. A. Smith

Dear Brother

I feel much anoyed by a Salt Lake Tribune sent me of the 16th Inst. containing a piece on the right of succesion to the Presidency of the Church in case of the death of President Brigham Young. You will probably have read it? I feel under no compliment to the left side of the house for advocating, in any way, any right to succeed to that elevated position, neither do I feel flattered by their efforts.

A stamp & envelope was sent me with the paper inviting, I suppose, some communication touching the question but I declined their implied invitation and write to you instead.

I wish here to say that no person living or dead ever heard me express the wish, desire or intention to reach after that exalted position neither did I ever give place to the faintest or strongest wish or desire for that station even in my secret thoughts and meditations in case a vacancy should occur. I cannot help what the Tribune says or publishes. Right or wrong, I have my own opinion with regard to a successor of Prest. Brigham Young and that opinion I expressed to Mayor Powel in conversation with him a few weeks since in which he raised the question as to the successorship to lead the Church I told him that the just and pure in heart amongst the Saints have unmistakable evidence of the calling of God of our present leader after the death of Joseph Smith. It was clearly manifest on whom the Mantle of the martyred Prophet fell and when it became necessary to appoint a successor God would point out the man by unmistakable evidences of His selection and that it became no aspirant to seek for that position and that I rested perfectly easy with regard to the matter and advised every body else to leave Gods business in his own hands I suppose some have imagined I would seek for that station if I outlive President Young but such thoughts are vain and groundless though they may exist in the minds of some but they never existed in my mind at any period of my lfe.

I feel the infirmities of age creeping upon me and if I can only magnify and honor my present position, I will therewith be content.

It looks to me as if lively and rather troublesome times are coming upon the Church and that it stands me in hand as well as every body else to feel after God.

May you live long upon this earth. Also Presidents Young and Wells and escape your enemies and I will live as long as I can

God bless Zion and bring off his Priesthood in triumph.

Your Brother in the Gospel

Orson Hyde

P.S. I hope to see you all soon.[34]

For a few years, the succession question regarding Elders Hyde, Pratt, and Taylor was not addressed. John Henry Smith “was present at a conversation between Prest Young and his father [George A. Smith] when the question of moving Bro. Hyde and Orson Pratt back in the quorum came up. Geo. A. Smith said [he remembered] Prest Young [saying]: ‘I have always counselled against making this change, hoping that Brother Hyde might die and thus be spared that humiliation; but seeing how sick you have been for some time I feared the consequences if you should have died. I shall no longer oppose the move.’”[35] This discussion must have taken place some time late in 1874 or early in 1875, for this is when President Young first became ill.[36] Myrtle Stevens Hyde, Orson Hyde’s biographer, mentions that there were discussions connected to the April 1875 general conference regarding this issue; however, no sources are given. The only evidence that may suggest that Elders Hyde and Pratt were informed of the change is that Orson Pratt was asked to come to the First Presidency’s office on April 9 the day before the change occurred.[37] On April 10, Elder George Q. Cannon read the names of the authorities of the Church for a sustaining vote and named John Taylor and Wilford Woodruff in front of Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt.

Another article in the Salt Lake Tribune appeared soon after this change in seniority saying that Orson Hyde has been “degraded by his dread master to third man in the apostolic ranks” and that Elder John Taylor had been “promoted” to the senior man in the quorum.[38] Speculation about those involved in the change circulated throughout the valley, but evidence about how each Apostle felt has already been mentioned. Each Apostle had consideration for the others’ feelings and had the utmost respect for each other. Orson Pratt later published an affidavit in the Deseret News affirming his support for the change: “I unreservedly endorse John Taylor.”[39] The wonder of all this is that although Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt were “sorely chastened” for “seeking occasion against” the Church and their brethren, each forgave them in their hearts and became reconciled to each other and the Church. They both acknowledged the error of their ways in those early days and accepted the consequences of those actions years later. The effects of this change were remembered for years. When Hyrum M. Smith was placed into the Quorum of the Twelve in 1901, President Joseph F. Smith said:

I want to impress upon your mind that the law of God is the supreme law and that the will of God is the supreme will and that no authority on the earth is entitled to develop the law, as aforesaid, but the First Presidency and Twelve Apostles. You must be loyal and true to them—you must never falter or rebel. President Young told me upon one occasion that no man in the quorum of Apostles who falters or rebels can ever attain to the presidency of the church. And because they faltered, Orson Pratt and Orson Hyde lost their place of seniority in the quorum, and were consequently thrown out of the line to the presidency. Elder [Hyrum]Smith said he know[s] this to be the work of God and would endeavor to [do] his duty, if ordained an apostle. Elder Hyrum Smith was then ordained a high priest and an apostle in the quorum of the Twelve Apostles, under the hands of all present, Pres. Jos. F. Smith being mouth.[40]

Thus the third precept in the succession question was complete. Seniority is based on continuous service in the quorum without interruption.

Fourth precept: Although a man may be the senior Apostle, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles must pass a motion to reorganize the First Presidency. Then the Quorum of the Twelve unanimously selects the new president, and he is sustained by the body of the Church.

After the death of Brigham Young in August of 1877, the weight of the Church fell from the First Presidency to the Twelve like it had in 1844 after Joseph Smith died. On September 4, 1877, the Twelve met in council. Wilford Woodruff records: “The Apostles met in Council and agreed to take their place as the presiding Quorum of the Church and bear off the kingdom as they did after the Death of Joseph and they voted John Taylor as the Presidt of the Twelve Apostles and John W. Young & D. H. Wells voted with us and they are to stand as Councillors to the Twelve as they did to Brigham Young.”[41]

John Taylor as the senior Apostle and President of the Quorum of the Twelve felt humble indeed, for at the conference just weeks later he said while addressing the congregation, “I did not wish to put myself forward [as President of the Twelve and the Church], nor have I, as the Twelve here can bear me witness. . . . I have not had any more hand in these affairs than any of the members of my Quorum; but I am happy to say that in all matters upon which we have deliberated, we have been of one heart and one mind.”[42]

John Taylor led the Church as President of the Quorum of the Twelve for the next three years. Then in October of 1880 the First Presidency of the Church was reorganized, and John Taylor was sustained as President with George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. Smith as counselors.

At the Friday session of the conference, President Cannon addressed an issue that had pressed upon the minds of the Saints for the last three years, he said:

Well . . . says one, Why cannot you organize a First Presidency now, if the Twelve have this authority? . . . I suspect you would like to know why a man and his two Counselors are not singled out, called and set apart by the voice of the people at this Conference, as the First Presidency of the Church? The reason is simply this: the Lord has not revealed it to us; he has not commanded us to do this, and until he does require this at our hands, we shall not do it. . . . When the voice of God comes, when it shall be the counsel [of] our Heavenly Father that a First Presidency shall be again organized, the Quorum of the Twelve will be organized in its fullness as before. Therefore you can wait, as well as we, for the voice of the Lord.[43]

Wilford Woodruff related that “at the close of the Meeting we the Apostles met in Council, and debated upon the propriety of Organizing the first Presidency. We had held several Councils upon this subjet and we finally left the subjet untill another Meeting.”[44]

The next evening, on October 9, 1880, “the Apostle then met in Council at 6 oclock and Decided to Organize the first Presidency of the Church. Wilford Woodruff Nominated John Taylor to be the Presidet . . . and it was Carried unanimously. Presidet John Taylor then Chose George Q Cannon as his first Councillor and Joseph F Smith as his Second councillor. It was then Moved seconded and Carried Unanimously that Wilford Woodruff Should be the Presidet of the Twelve Apostles.”[45]

Sunday, October 10, 1880, was truly historic. Wilford Woodruff said of the proceedings, “This is a great day to Israel.”[46] The second Sunday session began at 2:00 p.m. with the priesthood sitting in quorums in a solemn assembly. It should be remembered that the Prophet Joseph Smith received a revelation regarding the First Presidency on March 28, 1835, which is now section 107 of the Doctrine and Covenants: “Of the Melchizedek Priesthood, three Presiding High Priests, chosen by the body, appointed and ordained to that office, and upheld by the confidence, faith, and prayer of the church, form a quorum of the Presidency of the Church” (D&C 107:22). Within this revelation is the requirement that the three presiding high priests must be “chosen by the body” of the priesthood.[47] They must also be “upheld by the confidence, faith, and prayer of the church.”

A grand and impressive manner for sustaining a new President to the Church and First Presidency was started with President John Taylor’s administration. There had been solemn assemblies before, but never one to sustain a new First Presidency.

On the present occasion the Apostles occupied the stand set apart for their use in the great Tabernacle. . . . Apostle Orson Pratt, with hair and full beard, made gloriously white by the frosts of sixty-nine winters, presented the several motions to be acted upon. The manner of voting was for the proposition to be presented to each quorum severally, except in the case of the Priests, Teachers and Deacons, who voted all together as the Lesser Priesthood; the members of each quorum rose to their feet as the question was presented and raised the right hand in token of assent, or, if any were opposed to the proposition, they could make it manifest in the same way after the affirmative vote had been taken.

The order in which the quorums voted was as follows: First, the Twelve Apostles; Second, the Patriarchs, Presidents of Stakes, their Counselors, and the High Councils; Third, the High Priests; Fourth, the Seventies; Fifth, the Elders; Sixth, the Bishops and their Counselors; Seventh, the Lesser Priesthood. After this the Presidents of the quorums voted on the question and it was then put to the entire assembly which arose en masse and voted in the same manner.[48]

As the sustaining was unanimous throughout all the quorums of the priesthood, the voting was “received as a Law to govern the Church.”[49] This pattern has been followed for every new First Presidency from that time forth. Thus the final precept for succession to the Presidency of the Church had been established, which we follow to this day. Although a man may be the senior apostle, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles must pass a motion to reorganize the First Presidency, then the Quorum of the Twelve unanimously selects the new president, and he is sustained by the body of the Church.

Had all of these precepts of succession not come about during John Taylor’s life he would not have been the third President of the The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The first and second precept, allowed John Taylor’s name to be placed above Wilford Woodruff’s. Without this, since President Woodruff outlived him, John Taylor never would have become President of the Church. The third precept allowed John Taylor’s name to be placed above Elders Hyde and Pratt. If this had not been done Elder Hyde would have led the Church as President of the Twelve from 1877 to his death in November of 1878. Elder Pratt then would have led the Church from 1878 to his death in October 1881, thus taking away four years from John Taylor’s presidency, which lasted a decade. It is evident that in 1838, when John Taylor was named an Apostle, the Lord had his eye on him. The Lord knew from the beginning and has had his plan on how seniority would be governed, although it took many years from when the quorum was established to make all the precepts clear. By studying the life of John Taylor as he moved through the ranks of the Quorum of the Twelve, we can see the Lord revealing his principles regarding succession “line upon line, precept upon precept” (2 Nephi 28:30; see also D&C 98:12; Isaiah 28:10–13).

Notes

[1] On December 18, 1995, President Gordon B. Hinckley declared how a man becomes President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The occasion was an interview with Mike Wallace of 60 Minutes. Wallace asked, “How do you get to be President?” President Hinckley responded: “In 1961 I was called as a member of the Council of the Twelve Apostles, and through the years I moved up through the ranks of that circle until I became the senior Apostle. When the last President of the Church passed away, I was the senior Apostle, and the senior Apostle succeeds to the office of President of the Church. It’s the smoothest kind of succession that you could see in this world. It takes place very quietly, without election, without fanfare, without campaigning, without anything of that kind. It works” (“Excerpts from an Interview with Mike Wallace of 60 Minutes, December 18, 1995,” Discourses of Gordon B. Hinckley [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2004], 1:504).

[2] Age does seem to play a role in seniority when more than one Apostle is called on the same date. The best example of this is on February 12, 1849, when Charles C. Rich, Lorenzo Snow, Erastus Snow, and Franklin D. Richards were all called to the Twelve on the same day. Brother Rich was the senior because of his age, Lorenzo next, and so on. There have been many instances where this has happened in the Twelve. One of the most important was the call of Spencer W. Kimball and Ezra Taft Benson. Both of these men would become Presidents of the Church. The most modern example is the calling and ordaining of Elders Dieter F. Uchtdorf and David A. Bednar on October 2, 2004. There is one exception to this. On April 9, 1906, George F. Richards (forty-five), Orson F. Whitney (fifty), and David O. McKay (thirty-two) were called and placed in the Quorum in this order.

Elder John Taylor had this to say as early as 1851 regarding seniority, “The First Presidency has authority over all matters pertaining to the Church. The next in order are the Twelve Apostles, whose calling is to preach the gospel, or see it preached, to all the world. They hold the same authority in all parts of the world that the First Presidency do at home, and act under their direction. They are called by revelation and sanctioned by the people. The Twelve have a president. . . . This presidency is obtained by seniority of age and ordination” (“The Organization of the Church,” Millennial Star, November 1851, 337–38).

“The ranking of apostles according to their temporal ages pertained only to the initial organization of the Twelve. Prior to 1844, a combined criterion of chronological age and date of ordination was used for determining the relative positions of the members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Only when two apostles were set apart on the same day did age determine their seniority.” Milton V. Backman Jr., The Heavens Resound: A History of the Latter-day Saints in Ohio, 1830–1838 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 261.

[3] Interruption in the quorum is only defined as a loss of place in the quorum because of disciplinary action and not a call to serve as a counselor in the First Presidency. Those called from the Quorum of the Twelve to the First Presidency maintain their seniority in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

[4] Kirtland High Council Minutes, December 1832–November 1837, typescript, p. 187, Church History Library, Salt Lake City; see also Patriarchal Blessings Book, vol. 1, May 2, 1835, Church History Library; Joseph E. Taylor, “Priesthood—What Is It? Its Restoration,” Improvement Era, September 1901.

[5] It can be seen here from the minutes of the Grand Council on May 2 that the Twelve are named in descending order by age. Some question arises from the minutes whether more details were given regarding seniority. If the minutes are read with no assumptions or interpretation and only at face value, it appears that this seniority based on age was limited to their council meetings, because junior members were to preside also at these meeting in their turns and then it was to begin again with the eldest. These minutes alone do not state that Thomas B. Marsh was called by the Lord as the President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, although being named the “head” member alludes to it. The oldest historical record and the first place that Thomas B. Marsh is named as President of the Quorum of the Twelve is in the Kirtland temple, January 22, 1836. Here Joseph Smith calls Thomas B. Marsh “president of the 12” (Joseph Smith Collection, 1827–1844, January 16, 1836–January 22, 1836, Church History Library; see also Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. [Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1954], 2:382).

[6] Elders Boynton left his calling to attend to other occupations and was released from the Twelve on September 3, 1837. Elder Boynton blamed his difficulties to the failure of the Kirtland bank, stating that he understood the bank was instituted by the will of God, and he had been told that it should never fail. Joseph Smith stated no one had authority from him to say the bank would never fail, for he had always said that unless the institution was conducted on righteous principles it would not stand. A vote was then taken to know if the congregation was satisfied with Elder Boynton’s confession, and they were not satisfied and he was released.

On April 13, 1838, Luke S. Johnson was excommunicated for similar reasons, but later returned to the Church and crossed the plains with the Saints. His brother Lyman E. Johnson was also excommunicated the same day for several reasons which amount to being dishonest. On May 11, 1838, William McLellin said that he had no confidence in the Presidency of the Church and was excommunicated.

[7] Orson F. Whitney, Life of Heber C. Kimball, an Apostle (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1888), 199; see also Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 3:46.

[8] B. H. Roberts states in his biography of John Taylor, “In the fall of 1837, Elder Taylor received word from the Prophet Joseph that he would be chosen to fill one of the vacancies in the quorum of Apostles. This call to the Apostleship, found Elder Taylor busily engaged in the ministry. He had previously received a manifestation that he would be called to that high office in the Church, but fearing that it might be from the devil he wisely kept it hidden in his own breast. Now, however, he had been chosen to that place by the voice of God through His Prophet; but while his heart rejoiced at the thought that he was known of the Lord, and considered worthy by Him to stand in this exalted station in the Church of Christ, he bore his new honors with becoming modesty.”

“There is a revelation in the Doctrine & Covenants, Sec 118, that was given at Far West, on the 8th of July, 1838, in which John Taylor, John E. Page, Wilford Woodruff and Willard Richards, are called to the Apostleship; and direction is given that they should be officially notified of their appointment. But it is quite evident that Elder Taylor was notified of his appointment previous to July 8th, 1838, as he wound up his affairs and prepared to leave Canada, because of his being informed of this call to the Apostleship in the fall of 1837” (Life of John Taylor [Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon & Sons, 1892], 47–48).

Although Roberts states that John Taylor was told by the Prophet in 1837 of his call, no creditable sources can be found to back this up. Taylor himself states that the first time he knew of the call was by the Spirit sometime between July of 1838 and the intervening weeks until the letter came informing him of his call.

[9] John Taylor, The Gospel Kingdom: Selections from the Writings and Discourses of John Taylor, ed. G. Homer Durham, Deseret Book, 1943), 190.

[10] Donald Q. Cannon and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., Far West Record: Minutes of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1844 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 210.

[11] Taylor, The Gospel Kingdom, 191.

[12] See General Conference Minutes or Conference Reports where the Twelve Apostles are sustained from 1839 to April 1861. Wilford Woodruff’s name always appears before John Taylor.

[13] Church History Library, ms 155, box 2 folder 3, January 16, 1839.

[14] Gary James Bergera, Conflict in the Quorum (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, Salt Lake City 2002), 262.

[15] Church Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 1839–circa 1882, Church History Library, 136–37.

[16] Church Historian’s Office, History of the Church, 437; emphasis added.

[17] See note 4.

[18] Hoyt W. Brewster Jr., Doctrine and Covenants Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1996), 22. While some believe that Paul was just an Apostle and not a member of the Twelve, others believe Paul was a member of the Twelve. See Richard Lloyd Anderson, Understanding Paul (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1991), 36.

[19] For insights into these four brethren and the succession question, see Todd Compton, “John Willard Young, Brigham Young, and the Development of Presidential Succession in the LDS Church,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 35, no. 4 (Winter 2002): 111–34.

[20] Church Historian’s Office, Journal, 1844–1879, Church History Library, 252.

[21] Eugene E. Campbell, Establishing Zion: The Mormon Church in the American West, 1847–1869 (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1988), 154. See also Wilford Woodruff, Historians Private Journal (1858–78), April 17, 1864, as cited by D. Michael Quinn, The Mormon Hierarchy: Extensions of Powers (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1997), 164.

[22] Scott G. Kenney ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1983), 6:289–90.

[23] “It was unanimously decided that the acceptance of a member into the council or quorum of the Twelve fixed his rank or position in the Apostleship. That the Apostles took precedence from the date they entered the quorum. Thus today, President Snow is the senior Apostle. President George Q. Cannon next, myself next, Brigham Young next, Francis M. Lyman next, and so on to the last one received into the quorum. In the case of the death of President Snow, President Cannon surviving him, would succeed to the Presidency, and so on according to seniority in the Apostleship of the Twelve; that ordination to the Apostleship under the hands of any Apostle other than to fill a vacancy in the quorum, and authorized by the General Authorities of the Church did not count in precedence; that if the First Presidency were dissolved by the death of the President, his counselors having been ordained Apostles in the Quorum of the Twelve would resume their places in the quorum, according to the seniority of their ordinations into that quorum. This important ruling settles a long unsettled point, and is most timely.”

Joseph Fielding Smith, Life of Joseph F. Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1938), 311.

[24] See Bergera, Conflict in the Quorum.

[25] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1938), 1:472–73.

[26] Joseph Fielding Smith, Essentials in Church History (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1950), 664.

[27] Smith, Essentials in Church History, 188–89.

[28] Taylor, Gospel Kingdom, 187.

[29] Taylor, Gospel Kingdom, 193.

[30] Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, The Words of Joseph Smith: The Contemporary Accounts of the Nauvoo Discourses of the Prophet Joseph (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 146.

[31] Smith, History of the Church, 5:255–56.

[32] Taylor, Gospel Kingdom, 191–2.

[33] “The Two Orsons and the Succession,” Salt Lake Tribune, September 16, 1871, as quoted in Gary James Bergera, Conflict in the Quorum, 266.

[34] George A. Smith Papers, 1834–1875, September 23, 1871, Church History Library, ms 1322, box 8, folder 2, September 23, 1871.

[35] John P. Hatch, ed., Danish Apostle: The Diaries of Anthon H. Lund, 1890–1921 (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2006), 14.

[36] “On account of his weakened health the President decided to depart for St. George earlier this year than previously. On October 29th [1874], accompanied by George A. Smith, he left Salt Lake City ‘by special train’ for Provo. Here he remained for a few days to rest and recuperate, and then began the balance of the journey by carriage. Turning off through Salt Creek pass he visited the settlements in Sanpete and Sevier counties. On November 5th, he departed from Richfield ‘by way of Cove Creek’ for Beaver and Cedar City, where short stops were made. As the journey continued, his health improved, and the teams were pressed forward more rapidly, until George A. Smith could wire from St. George on November 11th: ‘President Young and party arrived here at 1 o’clock today. The President’s health is rapidly improving, and all other members of the company are well’ (Preston Nibley, Brigham Young: The Man and His Work, 4th ed., 510).

[37] Church Historian’s Office, Journal, 1844–1879, April 9, 1875, Church History Library, CR 100 1.

[38] Salt Lake Tribune, April 13, 1875, as quoted in Steven H. Heath, Notes on Apostolic Succession Dialogue 20, no. 2 (Summer 1987): 44–45.

[39] Susan Easton Black, Who’s Who in the Doctrine and Covenants (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1997), 229; see also Orson Pratt affidavit, Deseret News, October 1, 1877.

[40] Stan Larson, ed., The Apostolic Diaries of Rudger Clawson (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1993), 342.

[41] Kenney, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 7:372.

[42] John Taylor, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–86), 120.

[43] George Q. Cannon, in Journal of Discourses, 19:236–37.

[44] Kenney, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 7:594.

[45] Kenney, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 7:495.

[46] Kenney, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 7:495.

[47] Harold B. Lee stated of this passage from Doctrine and Covenants 107, “Second, they were to be chosen by the body (which has been construed to be the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles)” (Harold B. Lee, “May the Kingdom of God Go Forth,” Ensign, January 1973), 23.

[48] Roberts, Life of John Taylor, 340–41.

[49] Dean C. Jessee, ed., The Personal Writings of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1984), 166.